INTRODUCTION AND STUDY SITE

Universal aims of modern societies lie in assuring successful development, welfare, and continuous improvement in all life dimensions.Sharpley (2014) believes that successful tourism development largely depends on the harmonious functioning of stakeholders and the quality of their relationships. Stakeholders’, particularly hosts’ and guests’, satisfaction is remarkably interrelated and determined through their perceptions of tourism impacts (Andriotis and Vaughan 2003). In scientific literature, an immense volume of studies can be found dealing with tourism impacts perceptions, mainly from the residents’ perspective (Vareiro, Remoaldo and Cadima Ribeiro 2013;Sharpley 2014;García, Vázquez and Macías 2015). Tourism impacts and their interpretation through the prism of destination life stage, residents’ involvement in decision-making processes, socio-demographic variables, the type of tourism and its dynamics are the most frequent researched subject in the social science literature. This four-decade-old research topic still holds a considerable interest among scholars, besides it inevitably concerns tourism management due to its applicable and operational outcomes, which engineers the successful tourism development. Reason for actuality of this topic is at least threefold: (1) residents care a great deal about how tourism impacts their lives, (2) sustainable development is impossible without participation of residents in tourism development and planning process (Woosnam 2012) and (3) ever-growing competition for resources and sustainable tourism development (Woosnam, Erul and Ribeiro 2017). Indeed, residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts are meaningful for tourism management in understanding the patterns of their response and reactions, which in turn has a huge effect on the tourists visiting the destination: specifically, satisfied residents; proud, self-confident, with positive place identity and image affect the tourists very intensively; in fact, their attitude greatly influences tourists’ overall destination experiences.

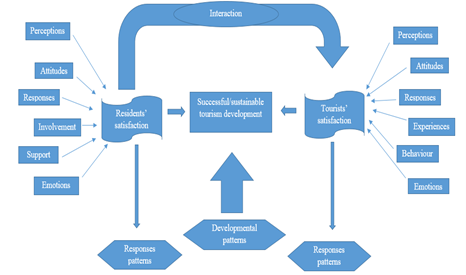

Understanding of perceptions, attitudes, opinions, responses, reactions and behaviour intentions of stakeholders and more importantly, distinctions among them, is fundamental to successful and sustainable tourism development (Sharpley, 2014). Most recent study-finding recommendations emphasise residents’ involvement in the decision-making process in tourism development due to the numerous beneficial contributions of their participation (Vareiro, Remoaldo and Cadima Ribeiro 2013;García, Vázquez and Macías 2015;Wang and Chen 2015;Woo, Kim and Uysal 2015;Šegota, Mihalič and Kuščer 2017). Successful and sustainable tourism development is achievable only if residents support it and feel empowered to participate in the process. Furthermore, their active involvement and informedness regarding the tourism planning process represent an essential signpost for tourism management and a variety of adequate developmental patterns.Yeh (2019) demonstrates that tourism involvement positively influences organisational commitment. Both tourism involvement and organisational commitment positively influence organisational citizenship behaviour (Yao, Qiu and Wei, 2019). Residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts, along with their involvement in planning processes, might provide comprehensive insight over their support and serve as a solid basis for further tourism development.

In this article, we examine residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and their support for tourism development in two similar, close tourism destinations: Portorož and Opatija. Both have a similar history of tourism development as well as tourist offer. Rest and recreation is also still a dominant tourism product, mostly because of natural resources, pleasant climate, Adriatic Sea and pristine environment. Both are coastal destinations, with a year-round tourism, mainly due to developed health resorts and congress tourism (Uran Maravić, Gračan and Zadel, 2015). Intable 1, we present some numbers to compare shortly these two destinations.

*destination Portorož & Piran Source: Statistical offices of Slovenia and Croatiahttps://www.dzs.hr/Hrv_Eng/publication/2019/SI-1639.pdf

There is an urgent need for strategic shifts in development on the crossroads that both destinations have approached. The mature seaside destinations share common historical development of tourism from the time of so-called Austrian Riviera in the golden era of the tourism in the middle of the 19th century, through the modern ages of mass tourism in the middle of the 20th century as a part of former Yugoslavia. Nowadays, the destinations are coping with seasonality and rejuvenation issues due to the tourism market turbulence and growing competition in the Mediterranean basin. Nonetheless, Portorož and Opatija are two major and among the most visited seaside destinations in the north-eastern Adriatic seaside region (Vodeb and Nemec Rudež 2016). They were interdependent throughout history until the 1990s when they became parts of two independent countries: Slovenia and Croatia. Although they share similar cultural context and tourism offerings addressing the same segments of tourists (Prašnikar, Brenčič- Makovec and Knežević-Cvelbar 2006), especially in the high season, the two destinations remain different in visitors’ perception. Opatija is perceived as more competitive than Portorož concerning its historical and architectural sites and gastronomy, whereas Portorož has a competitive advantage in congress facilities and saltpans (Vodeb and Nemec Rudež 2016). In previous investigations (Vodeb and Nemec Rudež 2017), local connections and accessibility rated low; conversely, safety, hospitality, and cultural richness were rated high by tourists in Opatija. The market supply-side, in contrast, recognises the destination vicinity of source markets and destination accessibility as the most important competitive advantage of Opatija (Vodeb and Nemec Rudež 2016) showing the gap of destination attributes perception between the market supply-side and demand-side. Likewise,Smolčić Jurdana and Soldić Frleta (2011) found that tourists assessed the beach rather critically; but from the supply-side view, it represents its main destination attribute.Zabukovec Baruca, Nemec Rudež and Podovšovnik Axelsson (2012) identified that safety and tidiness are important for tourists to Portorož, while nightlife and entertainment are of low importance.

Similarly,Blažević and Peršić (2012) confirm that tourists in Opatija are most satisfied with natural beauty, the hospitality of people, and the tidiness of the destination.Krstinić Nižić (2014) suggests that residents in the Kvarner region are more critical but also more aware of the need for improvement in all elements of the tourism services and facilities. The contribution of this work makes to the extant literature regarding residents’ attitudes concerning tourism, exposes the paramount role of host-guest interaction and relationship, making it backbone of successful sustainable development of tourism destination. Investigating the residents’ perception of tourism might shed some new light on this issue regarding different stakeholders’ perceptions. Understanding the residents’ support for the sustainable development might help tourism planners to understand possible developmental guidelines and patterns leading closer to sustainable and successful tourism development. Therefore, two research questions arise: first, “In which ways do the perceptions of tourism impacts affect residents support for further sustainable tourism development?”, and second, “Are there some differences between residents’ perceptions in Portorož and Opatija?”

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Sharpley (2014) argues that study of residents’ perceptions actually should be the study of host-guest interaction; however, in his comprehensive review of the topic, he concludes that most research focuses on residents and overlooks tourists. Furthermore, the main shortcoming, in his opinion, is the fact that research mainly tends to describe what residents perceive, rather than why and how they perceive it, which would disclose their responses and reactions. The latter is conditioned by a variety of factors, from personal values to socio-demographic variables (Sharpley 2014, 44). Hence, he suggests that research should consider responses and behaviour intent, not solely perceptions, because they represent only the surface due to the value-action gap (Sharpley 2014, 46).Ap (1992, 666) reports that “there is rather limited understanding of why residents respond to the impacts of tourism as they do and under what conditions they react to those impacts.” The conditions under which the impacts should be explained and understood are those to consider.Vargas-Sánchez, Porras-Bueno and Plaza-Mejía (2011) emphasise the importance of searching the reasons why residents support tourism development; moreover, they believe that it undoubtedly helps to establish models for proper developmental patterns.Woosnam (2012) explored how residents feel about tourists and how it factors their attitude about tourism development. Some researchers investigated how host-guest interaction can explain their attitudes towards tourism development Andereck et al. 2005;Lankford and Howard 1994; Teye, Sonmez and Sirakaya 2002 inWoosnam 2012). A pivotal principle of sustainable tourism lies in a host-guest relationship (Benckendorff and Lund-Durlacher 2013 inWoosnam et al. 2017), however it remains a contextual construct, asWoosnam, Aleshinloye, Van Winkle, and Qian (2014, 148) conclude that “much can be learned about the relationship while considering context”.Joo et al. (2020, 73) believe tourism can give a sense of political power to residents and residents’ participation in the tourism development process is essential to achieving more sustainable tourism development (Joo et al. 2020, 72). Resultantly, residents’ empowerment at the individual level fosters their engagement in tourism planning and development (Joo et al. 2020, 79).

We might assume that the research findings, based only on the perceptions cannot be implemented efficiently in the decision-making process of tourism management because they present only raw material and, as such, cannot be efficiently useful for tourism planners. Decoding of such data about residents’ perceptions is required to obtain applicable information for the decision-making process. We might illustrate the decoding process as the disclosure of cause-and-effect variables, which will lead from perceptions to responses. A corollary of that might be some recent studies assessing the spectrum of variables and factors that determine the residents’ perceptions and attitudes about tourism. These provide a huge step towards response patterns and data that are more useful for the tourism planners.

Most recently,Erul et al. (2020) forewarn that residents are crucial stakeholders in establishing successful sustainable tourism destinations. Therefore, they investigated emotional solidarity as a predictor of support for tourism development (Erul et al. 2020, 5) and found out that the level of support for future tourism is conditioned with their awareness of tourism importance and impacts perceiving. Indeed, residents’ attitude about tourism and its development can be affected by the feelings and degree of solidarity, residents’ experiences with tourists on an individual level (Woosnam 2012, 24), which is why Emotional solidarity scale (ESS) is becoming functional in explaining and predicting their tourism development support. In comparison to Social exchange theory (SET), criticised mostly for reducing host-guest relationships to economic perspectives, ESS introduces feelings and affections that are firm factors of relationships in tourism (Erul et al. 2020).

Simultaneously, different multidimensional and methodological approaches are examined in this area of research. Recently, more frequent combined, qualitative, and quantitative methodological approaches are employed, such as segmentation of residents’ perceptions as a meaningful tool for identifying the response patterns (Vareiro, Remoaldo and Cadima Ribeiro 2013;Šegota, Mihalič and Kuščer 2017). The so-called “none-forced” approach (Stylidis, Biran, Sit and Szivas 2014) in measuring impacts brings some novelty; residents are provided with a set of neutrally phrased statements considering perceptions of tourism and not a priori categorised impacts into positive, negative, economic, sociocultural, and similar. Impacts are given to the residents’ evaluation of the extent to which they perceive it as being positive or negative. This approach enables an insightful and comprehensive understanding of how perceived impacts influence residents’ support and with it strengthen its predictive power.

The concept of overtourism is usually related to destinations' development, negative impacts, and tourism policies and regulation.Verissimo et al. (2020) argue, although tourism excesses and conflicts have been studied for long, ‘overtourism' and ‘tourismphobia' have become usual terms, mainly within the past three years. Even though the adoption of the terms can be considered by some as a ‘trend', the in-depth analysis of the topics shed light on how ‘old' concepts can evolve to adapt to contemporary tourism issues (Verissimo et al., 2020). Additionally,Muler Gonzales, Coromina and Gali (2018) found that impact perceptions do not correspond to a willingness to accept more tourists. In fact, the impacts of tourism on conservation show greater consensus, while impacts on the availability of space for residents show links to other capacity indicators.

Lundberg (2017) introduces an evaluative component in the research of resident attitudes by importance measurement of tourism impacts with argumentation that tourism management should follow not only impacts perceptions but also their evaluative component in order to facilitate tourism planning efforts.

Residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards tourism impacts subject to the influence of numerous factors, variables and context, which we believe may help to divulge the response patterns. AsLankford, Chen, and Chen (1994, 224) conclude: “residents’ attitudes toward tourism are not simply the reflections of the residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts, but the result of interaction between residents’ perceptions and factors affecting their attitudes.” The most commonly measured variables are economic (economic dependence on tourism, tourism development, tourist area distance from home, access to recreational facilities, etc.) and socio-geographical variables (gender, age, education, income, etc.), external, internal or intrinsic and extrinsic values (García, Vázquez and Macías 2015). Residents’ perceptions of impacts regarding awareness and acceptedness transform over time and evolve considering the level of tourism development (Diedrich and García-Buades 2009;Vargas-Sánchez et al. 2011;Kim, Uysal and Sirgy 2013). The type of tourism (Vargas-Sánchez, do Valle, da Costa Mendes and Silva 2015), as well as residents’ place image (Stylidis, Biran, Sit and Szivas 2014) and place identity (Wang and Chen 2015), are frequently examined variables determining the perceptions. Affiliation with tourism (Woo, Uysal and Sirgy 2018), informedness and involvement in tourism development (Šegota, Mihalič and Kuščer 2017) life satisfaction and QOL concept (Woo, Kim and Uysal 2015) along with emotional solidarity and residents’ empowerment through knowledge of tourism impacts (Joo eta al. 2020;Woosnam 2012) are recently the most inspected variables regarding residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. Combinations of these variables and factors contribute to the detection of responses; reactions and behavioural intent and, therefore, may represent useful data for tourism planners.

Perception of impacts is the principal variable for explaining residents’ attitude towards tourism (Vargas-Sánchez et al. 2011;Vargas-Sánchez, do Valle, da Costa Mendes and Silva 2015) and understanding of residents’ attitudes is considered a vital ingredient of tourism planning and management (Sharpley 2014) because it reveals their support for further sustainable tourism development. Residents support is an essential factor in tourism development (Lee 2013;Strzelecka and Wicks 2015;Almeida-García, Peláez-Fernández, Balbuena-Vázquez and Cortés-Macias 2016;Woo, Uysal and Sirgy 2018) that provides successful sustainability. Support of residents is crucial for tourism because it constructs a major part of the overall tourist experience (Ap 1992).Diedrich and García-Buades (2009) warn that negative residents’ attitudes towards tourism are liable to have an adverse impulse on the tourist experience. Predicting the residents’ support helps to manoeuvre the tourism development according to the pace of community appreciation and expectation, which in turn results in stronger attachment, more positive attitudes and responses towards tourism. Researchers are striving to identify reliable predictors such as demographics, length of residency (Liang and Hui 2016), positive perceptions of economic and sociocultural impacts (Vargas-Sánchez et al. 2011;Kim, Uysal and Sirgy 2013), quality of life (Woo, Kim and Uysal 2015), place identity (Wang and Chen 2015) and others. Ultimately, they conclude that tourism should improve the quality of life and welfare of all stakeholders involved. Therefore, tourism planners should learn how to present tourism benefits through marketing and management techniques to obtain the residents’ participation, since positive perceptions of tourism impacts are significant in obtaining their support (Oviedo-Garcia, Castelanos-Verdugo and Martin-Ruiz 2007). Indeed,Camilleri (2016) emphasise the importance of fruitful communications and dialogue among all stakeholder groups for accomplishing responsible tourism.

Managing the tourism impacts structures the main part of the tourism planning process with the foremost goal in minimising the negative and maximising the positive impacts or tuning the right balance between them. Numerous most recent study-findings report that residents support and their involvement in the planning process are highly conditioned (Sharply 2014;Vareiro, Remoaldo and Cadima Ribeiro 2013;Almeida-García, Peláez-Fernández, Balbuena-Vázquez and Cortés-Macias 2016;Lundberg 2017;Šegota, Mihalič and Kuščer 2017).Diedrich and García-Buades (2009) emphasise the relevance of integrating the host community’s response to tourism development within the tourism planning process. Residents support is often understood as a behavioural intent toward tourism (Wang and Chen 2015), which enables us to assume that the support of residents greatly contributes to overall tourist satisfaction, which leads to long-term successful tourism outcomes.

Moreover,Vargas-Sánchez et al. (2011) believe that a favourable attitude of residents towards tourism generates positive interactions with tourists, enhancing their satisfaction, which indicates the immense importance of the researched issues. We may conclude that, by researching the residents’ responses to their perceptions and attitudes based on their feelings towards tourism and tourists (using Emotional solidarity theory (Woosnam 2012), we might get closer to understanding the host-guest interactions. The interaction itself seems to be the core of understanding and applying this knowledge to developmental processes in tourism. Researching the residents’ support for sustainable tourism development help to identify response patterns depending on their attitudes towards the impacts. Such patterns might help planners to find appropriate developmental patterns for the destination, which will contribute to community development and, as a corollary of that, enable an optimal tourism development pace. Indeed, tourism might be a great developmental opportunity if it considers residents, promotes their cultural and social expression, thus integrating the community at all levels.

Previous studies regarding attitudes of residents towards tourism development in Slovenia (Ambrož 2008) reveal place attachment, impacts perceptions and type of tourism to be the most influential variables.Ambrož (2008) discuss residents’ emotions function in their perceptions and attitudes explaining it within their beliefs, values, and experiences of the tourism impacts.Woosnamsʼ (2012) research also reveals the importance of emotions and shared beliefs in host-guest interaction. Furthermore, the residents’ level of involvement with the tourism industry and tourists shows some correlation with their attitudes, and the local community on the Slovenian coast is generally supportive and specifically recognises its positive effects (Vodeb and Medarić 2013). This corroborate the findings ofWoosnam et al. (2017, 645) that employment within tourism sector and dependence on tourism industry should be factored into how residents conceive their relationships with tourists. The above studies (Ambrož 2008;Vodeb and Medarić 2013) also reveal not only that tourism impacts are interrelated with the tourism development stage, but the claim for a proactive approach, since the level of tourism development influences the residents’ perception to a great extent.

According to the above literature review, we developed a conceptual model of elaborated variables and their relationships, which we present inFigure 1.

Source: Authors

The central position in our conceptual model is held by the universal goal, which is sustainable tourism development, believed to be the only way of gaining success in modern tourism society. The concept of sustainable tourism development implies an integration of all stakeholders in order to provide long-term development possibilities for all involved. Tourists’ satisfaction is the ultimate condition for gaining success in tourism, which is repeatedly confirmed by the fact that it is interrelated with residents’ satisfaction.Soldić Frleta (2014) provide empirical insights into the tourists and residents’ attitudes regarding Kvarner Bay islands (Croatia) tourism and its offer. The analysis of obtained results shows which elements of the tourism offer are considered as being the destination’s weak points by tourists and which are considered such by residents.Krstinić Nižić (2014) studies the problems and specific issues related to tourism through an analysis of the tourist’s, the resident’s and tourism management’s evaluation of the tourism offer elements related to space, environment and sustainable development in the Kvarner region. Results of both studies indicate that all target groups give reliable and actual basic quantitative and qualitative information about the attitudes of tourists, residents and tourism management. Feedback obtained based on their mutual relationship might serve as an instrument to implement sustainable destination development. Moreover,Joo et al. (2020) believe that emotional solidarity with residents’ impacts tourists’ perceptions of tourism, besides,Joo, Cho and Woosnam (2019) think that tourist affective bonds with destination can led to corresponding behaviour and it would be interesting to compare how residents and tourists think about tourism impacts and development.

Common researched elements of residents, and tourists’ satisfaction (perceptions, attitudes, responses, experiences, involvement, behaviour, support and emotions) create their response patterns, which we firmly believe might informed developmental patterns for tourism management. The application of developmental patterns generated on responses patterns of residents and tourists brings us closer to sustainable tourism development.

2. METHODOLOGY

This research was focused on determining how residents in Portorož and Opatija perceive tourism impacts, what their attitude is towards tourism, and how these affect their support for further sustainable tourism development. The most effective way of collecting and analysing data to obtain useful and reliable results was to conduct a survey. This quantitative approach enables a large number of respondents, thus better data. It also makes it easier to compare the results of both destinations when carrying out a comparative analysis to find any differences in perceptions and attitudes towards tourism between the two groups of residents. The survey took place in both destinations during the low season, at the same time at the beginning of 2018. In both destinations, a group of approximately 10 interviewers conducted a survey in public places (i.e. on streets, by grocery stores, post-offices, shopping centres, along the coast, etc.) during workdays and weekends, targeting local residents and selecting them by simple random sampling.

The residents were asked to answer a structured questionnaire on their position regarding tourism impacts. The questionnaire was obtained fromAbdool (2002) and was adapted to address the relevant issues of the two chosen destinations, and modified after validation by pilot testing to ensure an effective data delivery. The questionnaire consisted of two parts: the first with 32 statements on different aspects of living in the destination for which the respondents had to express their level of agreement from a five-point Likert-type scale (1 – I do not agree at all, 5 – I fully agree). The second part comprised demographic questions (age, gender, education, employment in tourism) and 11 questions on their satisfaction and opinion about sustainable tourism development. The survey was conducted in Portorož and Opatija by researchers to make sure the residents understood all the statements properly.

The two databases were later joined in order to conduct some inference data analysis using the statistical programme SPSS 21. According to the type of variables t-test and ANOVA were used for the analysis beside the descriptive statistics.

3. RESULTS

A total of 249 completed questionnaires were collected in Opatija, and 197 in Portorož. The distribution of demographic characteristics of residents in both destinations was approximately the same: most respondents were 16–25 years old (around 30%), followed by each consecutive age group in a lesser number. Around half were male, the other half female. Half were high school educated, 40% had college or university degree, the others elementary school or less, and just a few had masters or doctorate degrees. Most respondents (35%) were employed in other areas, more than 11% worked in tourism, 17% were retired, 10% unemployed, and others were still studying. Twenty-nine per cent of respondents in Opatija said they were involved in tourism in some manner, while there were 41% respondents like this in Portorož.

The results showed quite a lot of statistically significant differences in perceptions of tourism activities between residents of Portorož and the residents of Opatija. It seems that the residents of Portorož were far more unsatisfied with the way tourism is managed, compared to the residents of Opatija.

They both agreed that a local tourism organisation (LTO) should be responsible for tourism development; however, many residents (over 30%) in Portorož thought that the responsibility should be of public administration (PA) as well or a combination of LTO and PA.

Respondents in Portorož rated the activities of the local tourism organisation as insufficient or unsatisfactory, as opposed to respondents from Opatija, where the majority rated it positively (P-value=0.000). Very similar were the results regarding cooperation between local producers and hospitality providers. Most respondents in Portorož felt this was just satisfactory or even unsatisfactory, as opposed to very good. In Opatija, more than half of the respondents felt that traditional local products were sufficiently included in the tourism offers; however, in Portorož, almost 60% of respondents felt that these were not included in the offer sufficiently.

Respondents in both destinations were mostly satisfied with the possibility for the locals to use tourism infrastructure. Nevertheless, there were 28% unsatisfied respondents in Opatija and 38% in Portorož.

A significant difference was noted between respondents in Portorož and those in Opatija with the results regarding the threat of industrial development and excessive apartment construction to tourism. In both cases, respondents from Opatija show much more concern regarding tourism development than respondents in Portorož do.

Respondents at both destinations have a similar position on the exceeded carrying capacity during summer (P-value=0.955). Approximately half of them think the carrying capacity is exceeded during summer; the other half think it is not. Also, around 90% of respondents in both tourist destinations think that the locals should be informed and involved in decision-making processes (P-value=0.325).

| Location | Total | |||

| Opatija | Portorož | |||

| Opinion on destination tourism development | Positive | 162 | 64 | 226 |

| Negative | 21 | 46 | 67 | |

| Neutral | 66 | 87 | 153 | |

| Total | 249 | 197 | 446 | |

Source: Authors

A statistically significant difference was also noted between the respondents from Portorož and respondents from Opatija regarding their opinions on destination tourism development (Table 2). The majority of respondents in Opatija have a positive opinion about tourism development, while the results are quite different in Portorož. Most of the respondents have a neutral opinion. The results coincide with the previously mentioned discrepancies, in which the respondents in Portorož seem to be less satisfied with tourism in their town than their counterparts in Opatija.

After conducting a t-test to compare the means of levels of agreement with the 32 statements between respondents from Opatija and those from Portorož, the results showed many statistically significant differences, always in favour of Opatija’s higher mean (Table 3). Generally, we could deduce that respondents from Opatija perceive tourism and its impacts in a more positive way.

** The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Source: Authors

There were no statistically significant differences observed in less than half of the statements. The respondents from both destinations seemed to have a very similar perception about the high importance of the involvement of residents in tourism planning and decision-making process. They agreed, to the same extent and quite homogenously, that increased tourism brings overcrowding in museums and restaurants, higher prices, risk of diseases, and traffic problems, as well as increased volume of waste.

In contrast, even though the results were less homogenous, both respondents’ group felt that tourism helps preserve cultural identity, assures better social well-being with jobs, contributes to destination sustainable development, and enhances ecological values. At the same time, they agreed to a certain extent that tourism professions increase among locals and that just a few locals benefit from tourism. However, they disagreed that tourism changes traditional culture and values and that it causes relationships to deteriorate.

It can be observed that respondents in both destinations showed their highest agreement with essentially similar statements. They both agreed strongly on the importance of residents’ involvement in planning, on the overcrowding in museums and restaurants, on a cleaner environment, and higher prices due to tourism. The respondents from Opatija seemed to appreciate the better infrastructure, the investments, and better roads and parking infrastructure more. In contrast, respondents from Portorož expressed their concern about the increased traffic issues, but they did notice social well-being benefits regarding jobs in tourism. Also, both respondents disagreed on the negative impacts of tourism, such as the risk of diseases, security issues, and an increase in organised crime. An interesting result emerged with the respondents from Portorož regarding the statements that the residents are well informed and that they are satisfied with the planning of destination development: the respondents disagreed with both statements. As the respondents in Portorož expressed their disagreement about tourism destroying the ecological values of the destination, the respondents in Opatija thought the opposite.

The importance of residents’ involvement in decision-making

Since respondents at both destinations rated the residents’ involvement in planning as very important, it made sense to investigate further the association of statements with the opinion about informing or involving the locals in decision-making.

| Group Statistics | |||||

| Locals should be informed/involved in decision-making | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| Bigger quantity of waste on streets | Yes | 179 | 3.3464 | 1.20515 | .09008 |

| No | 18 | 2.5556 | 1.19913 | .28264 | |

Source: Authors

It turned out that, based on their opinion on whether the locals should be involved in decision-making or not, respondents from Portorož agreed with all statements at the same level, except with the statement about the quantity of waste on streets (Table 4). Those who think that the locals should be informed and involved in decision-making estimated that tourism produces more waste on streets, while those who think that the locals should not be involved in decision-making showed disagreement with this statement by rating it below average (P-value=0.009).

Source: Authors

Statistically significant differences were observed in more statements between the two groups of residents from Opatija (Table 5). Those who think locals should be involved in decision-making agreed to a higher level that tourism ensures a better life standard (P-value=0.013), increases overcrowding in museums and restaurants (P-value=0.004), taxes and duties (P-value=0.017), brings improved appearance and cleanliness of streets (P-value=0.003). At the same time, they rated the increase in organised crime below average, compared to a higher level of agreement with this statement by respondents that think locals should not be involved in decision-making (P-value=0.002).

The importance of residents’ involvement in tourism (employment, property renting)

There were also some differences noted when comparing the results from Opatija and Portorož according to respondents’ personal involvement in tourism. In Portorož, the respondents from both groups agreed with most of the statements in the same way; statistically significant differences could be noticed with only two statements (Table 6).

Source: Authors

Those who were not involved in tourism showed a much higher level of agreement and proved to be even more homogenous with their rating of increased noise levels due to tourism compared to respondents who were personally involved in tourism (P-value=0.016). Moreover, the opposite turned out to be the case, in which those involved in tourism rated the contribution of tourism to destination development significantly higher than those who were not involved in tourism (P-value=0.029).

Respondents from Opatija also agreed with most statements in a rather similar fashion when considering their personal involvement in tourism. There were some more, but different statements compared to respondents from Portorož that resulted in statistically significant differences between respondents involved and those not involved in tourism (Table 7).

Source: Authors

Respondents who were personally involved in tourism expressed significantly higher levels of agreement compared to those who were not involved; when stating that tourism professions increase among locals (P-value=0.001), tourism enhances intercultural exchange with tourists (P-value=0.003), it helps preserve cultural identity and heritage (P-value=0.008), and diversify cultural content (P-value=0.009), as well as revive traditional customs and activities with locals (P-value=0.028). A statistically very significant difference could also be observed in the level of agreement with tourism contribution to enhancing ecological values (P-value=0.000), for which respondents involved in tourism agreed and those not involved rated their agreement lower than average. This finding was also confirmed with the reverse statement (that tourism destroys destination ecological values), the result between the two groups was significantly different in favour of higher agreement by respondents who were not involved in tourism, and rated lower than average by respondents who were involved in tourism (P-value=0.016). Both groups of respondents from Opatija expressed their level of agreement lower than average, thus showing disagreement with the statements about tourism imposing relationships deterioration (P-value=0.041) and risk of diseases (P-value=0.048). However, in both cases, respondents who were not involved in tourism disagreed significantly more than those who were involved in tourism.

Perceptions impact on residents’ support for sustainable tourism development

Investigating statistically significant differences in the levels of agreement with statements based on the opinion (positive, neutral, negative) on sustainable tourism development of the destination, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for both destinations and came across some very interesting results. These showed that respondents in both destinations did not show any significantly different agreement with approximately half of the statements, considering their positive, negative, or neutral positions on tourism development. In contrast, the other statements where differences in the levels of agreement between three groups of respondents with a positive, negative or neutral attitude towards tourism development could be observed. The statements with statistically significant differences are jointly presented inTable 8 for both destinations. We can see that respondents in both destinations did not agree with mostly the same statements on a same level. There were differences between groups with three more statements for respondents from Opatija (benefits outweigh disadvantages, increased traffic issues, and diversification of cultural content), and with one statement for respondents from Portorož (tourism impacts locals’ behavioural changes).

Source: Authors

In most cases, there were significant differences in the levels of agreement between all three groups; in some cases, the differences were insignificant between those with a positive and those with a neutral opinion on destination development, or between those with a negative and those with a neutral opinion. To understand the effect of perceptions on residents’ support for the development it is important to focus on the differences between those with positive and those with negative opinion on present state. It is more likely that those with a negative opinion would not show or give support to current tourism planners, while those with a positive would.

Even though ANOVA showed significant overall differences in all statements fromTable 8, it could be noticed in Post-Hoc tables (enclosed to the article) that, with some of the statements, respondents with a positive opinion did not respond differently, compared to those with a negative opinion. With those statements the statistically significant differences occurred only between respondents with a positive and neutral opinion, or between respondents with a negative and neutral opinion, however not between those with positive and those with negative opinion. The statements inTable 8, where differences between respondents with a positive and respondents with a negative opinion were insignificant, are marked with * (those statements had significant differences only between positive / neutral opinionated or between negative / neutral opinionated). Those appear to be only with the following statements in Portorož (Increase in taxes and duties, and Tourism impacts behavioural changes of locals, both with a significantly higher level of agreement by respondents with a negative opinion) and the following statements in Opatija (Increase in traffic issues, and Tourism destroys destination ecological values, also both with a significantly higher level of agreement by respondents with a negative opinion on destination sustainable development). We can deduce that tourism planners can count on support from both groups (positive and negative opinion) only by considering the joint agreement rate and improving the issue accordingly in order to satisfy also the neutrally opinionated residents.

All the other statements fromTable 8 were rated significantly different by respondents with positive and respondents with negative opinions on tourism development in both destinations. Most of them were rated with an approximately 0.5 to up to 1.5 higher grade by respondents with a positive opinion compared to respondents with a negative opinion in both destinations. Thus, giving the tourism planners an idea of which issues to address to get support also from residents that at the moment do not show support for current development. Expectedly, the statements with a negative connotation were rated with a higher level of agreement by respondents with a negative opinion about current development. The ratings differed for approximately 0.6 to 0.8 grade, only in one case (Risk of diseases in Opatija) the grade was almost 1.3 grade different.

A very interesting finding is the difference between the perception of respondents in Portorož and Opatija in the case of the number of locals that benefit from tourism. It seems that in Portorož respondents who support the current development agree that just a small number of locals benefit from tourism, while those with a negative opinion about development do not find this problem that alarming. While in Opatija the results were the opposite, where the supporters of current development do not agree with this statement as much as those who have a negative opinion on current development.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Decoding residents’ perceptions leads us to response patterns, conditioned by numerous factors and context deriving from the tourist destination, providing the tourism planners insightful intelligence to optimise their decision-making process as an essential part of sustainable tourism development. Their involvement in tourism planning highly conditions residents’ support for tourism development. More importantly, however, it directly influences tourists’ experience and satisfaction with the destination, as proved byAp (1992);Diedrich and García-Buades (2009) andWoosman (2012). Therefore, residents supporting tourism is the most reliable premise for successful and sustainable tourism development. By a systematic and proactive detection and consideration of host-guest interaction and relationship, we actually gain a reliable disclosure of filigree information needed for the planning process, which build and support the backbone of successful sustainable tourism destination.

This, we believe, is the main theoretical implication of this article. As a corollary of that, we studied the host-guest interactions, asSharply (2014) has suggested, namely the perspective of residents, which is the main limitation of this article, but it nevertheless motivates suggestions for further investigation. We recommend simultaneously assessing the tourists’ satisfaction and residents’ perceptions in the same destinations and verifying if the feedback loop in the proposed conceptual model (Figure 1) functions. Likewise,Joo et al. (2019) recommend the comparison of host-guest perceptions of tourism impacts and its further development. Using different frameworks (SET, TIAS, ESS etc.) or their combination may better explain the complex interaction and relationship of residents and tourists, as all of them contribute to understanding this phenomenon only in some perspectives, failing to present it absolutely and completely.

Practical implications of this research are several and very concrete. AsWoosnam et al, (2014) previously said that attitudes and feelings are not permanent, practitioners in tourism planning and sustainable development should focus on dynamic host-guest relationships. Friendliness and positive attitude are luckily highly contagious, which is why it could be very efficient to involve those passionate and enthusiastic residents about tourism, to promote sustainable tourism development through different media (local newspaper, radio, TV, social networks etc.), aiming to motivate and encourage local and regional stakeholders for sustainable tourism development. Besides, policy makers and planners should consider collaboration with wider community stakeholders (schools, local community organizations, healthcare etc.) to distribute the information about sustainable tourism benefits through workshops, meetings and structured focus groups. Another limitation is the methodological approach, which could be solely qualitative or at least combined, in other objective circumstances and within potential funding of the research. In addition, heterogenic perspectives among residents, different seasons of conducting the surveys and sample representativeness might be considered in further research opportunities. Further step in research might be to explore the techniques and approaches of cultivating the relationships among residents and tourists, measurement and predicting accuracy of their attitudes and support. Finally, residents’ perceptions should be studied in multiple comparable destinations to get more convincing evidence for generalization and applications of findings. Nevertheless, we shed some light on this topic, summarizing the latest knowledge and research results from the field.

To summarise, the results of this research show that residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and the support of its further sustainable development are mostly conditioned by their involvement in tourism and their informedness about it, which is in line with previous research (Woosnam et al., 2017;Šegota et al., 2017;Woo et al., 2018;Joo et al., 2020). Residents from both destinations strongly believe in the importance of the involvement in the decision-making process, though residents from Portorož assess the tourism development more neutrally compared to those in Opatija, who showed a much more positive attitude towards it.Erul et al. (2020) report that if people are aware of the importance of tourism, they are likely to perceive positive impacts and support further sustainable tourism development. Moreover,Joo et al. (2020) found that resident’s empowerment enhances their engagement in tourism planning and development. By increasing their knowledge of tourism (i. e. impacts), it is possible to foster their empowerment and activity within it. In addition, in Portorož, locals feel they are not well informed, nor satisfied with the planning of tourism destination development. Higher awareness of waste problems caused by tourism is evident by those who believe in the importance of involvement in decision-making processes. In contrast, in Opatija, those who rate the importance of involvement in decision-making process recognise better life standard, improved appearance and cleanliness of the destination along with increased overcrowding and taxes and duties.Pham, Andereck and Vogt (2019) claim that the destination’s main attractions lie in its pristine nature and cleanliness and that satisfaction with the environment is a significant component of the QOL concept. Residents in Opatija perceive tourism less critically than those in Portorož do. In the latter destination, those involved in tourism do point out the fact that tourism increases noise; however, they accept it more than those who are not directly involved in tourism. At the same time, they agree more that tourism contributes to destination development compared to those not directly involved in tourism. In contrast, in Opatija, locals involved in tourism activity recognise tourism’s contribution to enhancing the ecological values of the destination opposed to those not involved. Likewise,Woosnam et al. (2017) detected strong connection between resident’s involvement in tourism (i.e. employed in tourism industry) and their perceptions of tourism impacts.Muler Gonzales, Coromina and Gali (2018) also report of residents employed in tourism, who perceive mostly positive impacts and are prepared to endure costs to maximize benefits, much more than those who are not involved in tourism activity.

Furthermore, we can conclude that critical perceptions of impacts among residents grow with their awareness of tourism activities and that economic and social possibilities that tourism offers them, with their QOL awareness, ecological sensitivity and tradition of sustainable tourism development at the destination.Woosnam (2012) reports about recognition of tourism contribution (benefits) among residents who feel close to tourists.Pham, Andereck and Vogt (2019) found that satisfaction with environment greatly influence the residents’ QOL satisfaction and consequently affect their support for further tourism development.Gursoy, Ouyang, Nunkoo and Wei (2019, 325) note that residents support the tourism development when they perceive positive impacts regardless of tourism type. Besides, they observe that acceptance of tourism costs and their support to its development were stronger in developed regions (Gursoy, Ouyang, Nunkoo and Wei 2019). All the above-presented results proved that the perceptions of tourism impacts affect residents support for further tourism sustainable development. Data from the residents’ response are more than insightful and valuable for management and planners to consider in decision-making processes at both destinations, because of their clear and exact call for a joint and coordinating dialog.

We strongly advise that tourism management and planners take into serious consideration the residents, who are one of the most important stakeholders in the destination structure and their competent role in the further developmental process of the destination. By monitoring the shifts of residents’ perceptions and attitudes, it is possible to come closer to the obvious shifts of tourists’ responses, behaviours and emotions that destinations have approached in this mature stage for both destinations. That is hopefully a reliable route to optimal sustainable tourism development in the 21st century.