Introduction

How does the Gospel, and how does discipleship manifest in the American church today? What are the interrelationships between the two terms, and what are the consequences of deficiencies of either one? These questions are important because the presence or absence of discipleship in churches or how discipleship will be misunderstood and practiced, greatly (but not exclusively) depends on the way how Christians or churches define the Gospel message.

Troublesome symptoms are emerging and accelerating in American Protestant and Evangelical communities. If American churches are to grapple with these difficulties, we must first consider the connection, or the lack of connection between widely held American interpretations of the words “Gospel” (εὐαγγέλιον euaggelion) and “disciple” (μαθητής mathētēs). This is not to suggest some eisegetical amalgam of the two very specific words should be pondered, but rather, to assert that the Gospel exists to enable and induce an engaged and ongoing life as a disciple of Christ. And to assert partial renditions of the gospel reverse or devolve this relationship.

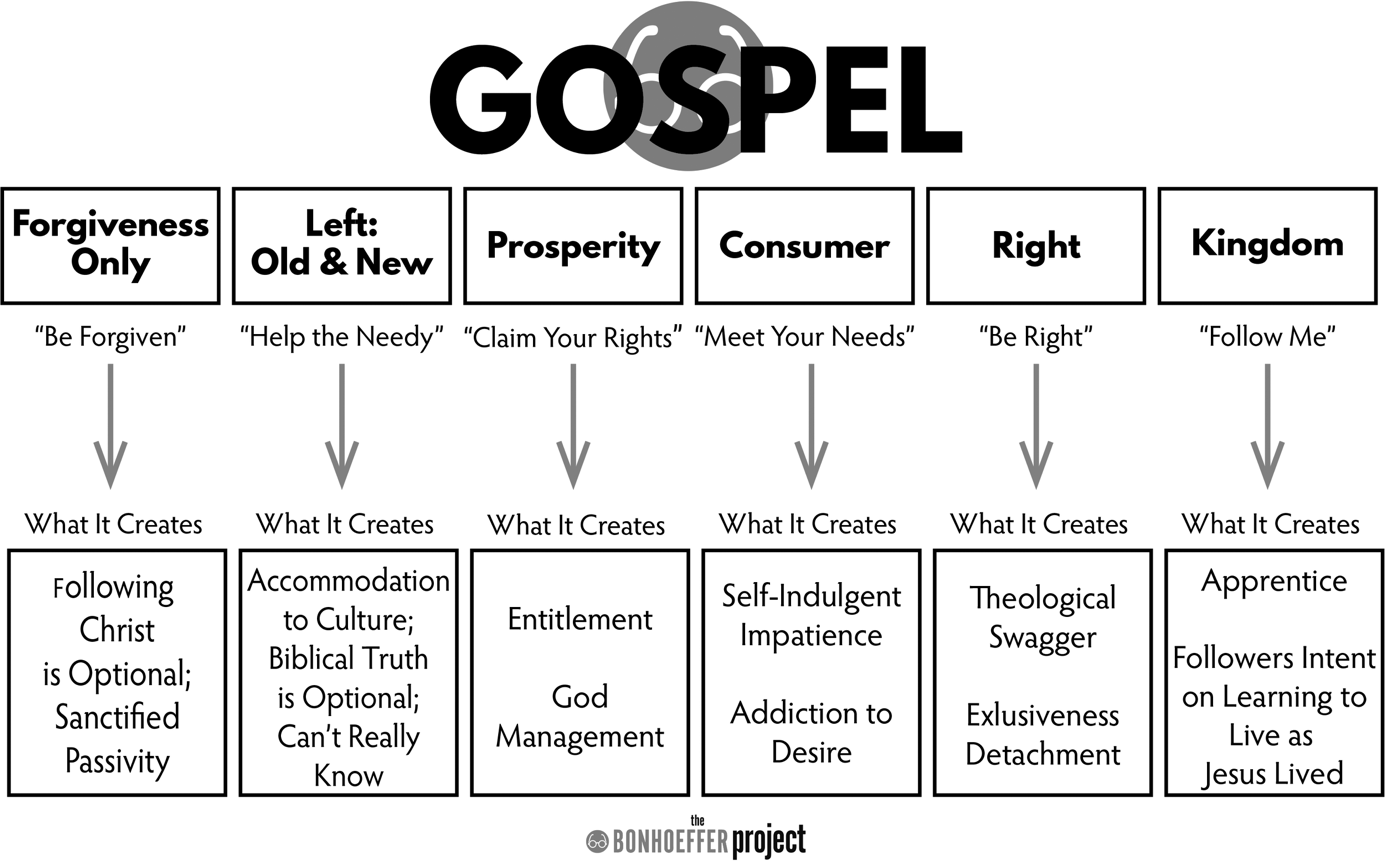

A thoughtful summary of this devolution can be found in the work of Bill Hull, a widely regarded American author, and speaker in Biblical discipleship. Hull (2021) suggests six variations of “Gospel Models” (hereinafter “GM”) in his organization “The Bonhoeffer Project” as shown here. Hull’s GM is not simply gospel descriptors. They shape discipleship. Why? The core tenet of a GM drives the behavioral outcomes in the lower boxes.1

We intend to briefly critique the first five of the six GMs as biblically inadequate—just as Hull already has - finally coming to dwell on the sixth model - “Kingdom/Follow Me,” which is Hull’s endorsed version of a proper biblical Gospel/disciple relationship. Accordingly, in two separate sections our task will be to demonstrate that:

Hull’s categorizations are supportable in American Christianity’s social trends, and they are each biblically inadequate.

Jesus’s great commission to “go” as disciples and to “make” disciples as Christ taught it in Matthew 28 and his life are conspicuously absent as the primacy of most American churches sampled in The Disciple Dilemma book research (Allen 2022, 229). It should be further noted that our research was confined to published mission statements for sampled churches.2

1. How Do Gospel Models Shape Discipleship?

Is discipleship distinct from, or is it the same as the gospel Christ bequeathed us? We answer this quickly, and we hope, simply: Yes – distinct and conjoined. Yes, the Gospel is precisely what Christ embedded in the lives of his disciples (cf. Luke 14:27-33; John 6:37-40). Yes, the Gospel is a life-long shaping and transformational journey – a metamorphosis of the individual. Therefore, the Gospel of Jesus cannot be reduced simplistically to a single moment in time’s choice or action (Rom 12:1-3). Lastly, yes, the Gospel, if understood, induces discipleship all the years ahead in the life of a Christian, a “disciple in progress” seeking to make others desire to be followers of Christ.

We shall not toy with “If/Then are we saved?” questions. We affirm that without the Gospel of Jesus Christ’s foreordained, elective, and propitiative work on the cross, and his resurrection, there simply is no case for discipleship. We likewise suggest that without a life of biblical discipleship, which is a Christ follower in ongoing transformation, in dying to self, taking up their cross, and intentionally pursuing Christ and his identity for them – prospects dim for long-term viability, humanely speaking (John 6:66). Herein lies the crux of the American disciple dilemma.

With minimal added comment we accept and affirm Hull’s assertion that his first five Western gospel models (GM’s) are exegetically unsupportable, yet prominent in many American churches – effectively a default way of thinking for such disciples. Other scholars have offered similar views using different terms to summarize Western evangelicalism’s partial gospels. Dallas Willard (2009) suggests three dysfunctional gospel groups: “Forgiven,” “Liberated” and “Churchmanship.” Victor Chan (2017) suggests the best labels of the partial gospels are “Eternal Life” focused, “Sin/Repentance” focused; “Prosperity” focused, or “Purpose-Driven” in focus. We stay with Hull’s labels as the reference point of this inquiry.

In decades past homogeneity in a denomination was the norm – the Methodists tended to lean deeply toward societal efforts, the Baptists sought to conquer an unevangelized world for Christ, while the Presbyterians sought to get everyone thinking rightly about soteriology. The Pentecostals pointed to the experiential Spirit events as the pinnacle of the Gospel, while the interdenominational sought the middle ground of compromise and theological tolerance as the right way. Eventually, the mainlines – mostly the Methodists, Lutherans, and Presbyterians began to shed a high view of Scripture as the Baptists began to raise drawbridges to isolate from an evil outside world (Keller 2021). It used to be more or less cleanly carved up that way in the denominations. Things are less consistent today viewed simply by theological brands. And there are a lot more brands. Rarely are there monolithic views in any one Christian community. This is not an improvement however, and brings us back to what Hull has categorized.

1.1. Forgiveness Only Gospel

The “Forgiveness Only” Gospel intends that salvation is the outcome for the believer – and everything else is secondary. This GM is particularly satisfying to the radical individualism of the American Christian because it quantifies a “do-this-get-that” transactional outcome. One checks a box, gets saved, and goes back to whatever they were doing before salvation came up. The 1974 Lausanne Conference’s emphasis on evangelism was fuel for such a Forgiveness focus – to get them saved. Today “Forgiveness’” discipling objectives zero in on get-saved as the ultimacy of John 3:16, or on the human actions for personal salvation to be effective. This forgiveness emphasis in Western Christianity dates back at least to the early 1800s (Fitzgerald 2017, 3–6). Hull argues that such a focus bankrupts the fuller call of Christ for the new believer – any notion of following Christ is “optional” under this paradigm.

In other words, once I am saved all else is discretionary but not necessary. In short, this model, perhaps unintentionally, orphans new believers to discover for themselves the true intentions of Christ in the ongoing life of a believer. Why? Because the people who introduced them to Christ have to move on to the next prospect. This GM of “Forgiveness” was once the near-exclusive landscape of Evangelical Western churches. The results seen in the trends of the evangelical church demonstrate this GM to be problematic (Stark 2008; Barna Research 2018; Pew Research Center 2019).

1.2. “Left” and “Right” Gospel

The terms “Left” and “Right” in American life are used to shorthand sociological stances on a range of cultural issues, typically the Left taking the liberalized view of economic, moral, and political topics, whilst the Right hews, typically to the conservative, or historically traditional view. We group these two Hull designations into one paragraph since the core issues are essentially identical, with diverse conclusions as the Right/Left outcomes.

Politically oriented “Left” and “Right” disciples may inhabit the same church or denomination, but they advocate for certain political or social doctrines as the greatest Gospel outcome, sometimes just dropping the Gospel part and going with the intended outcome. Both Left and Right are power structures, seeking conformity to moral fatwahs above any faith convictions. This colocation of Left and Right advocates in one location is not a demonstration of unity. Much of the Left/Right dissonance is generational today, as children reject parent-advocated views on what each thinks God deems good and right and true.

But it’s not all generational. One need look no further than the ongoing deconstruction across denominations. The United Methodist Church, the Episcopalians, Presbyterian USA, or the roiling Southern Baptist squabbles demonstrate that inside many local churches, a gospel identity of the “Left” and the “Right” is rending the unity of the local community of Christ. This divide means that a follower of Christ is either operating from “our” views of social justice, causal thinking, or political and social constructs – or the non-conformist is confused, stupid, or evil.3

1.3. Prosperity Gospel

“Prosperity” seekers, Hull says, have come for the entitlements of wealth, fame, or power as compensation for their ancestor’s tribulations, or for reparations from perceived social inequities which the Messiah would surely want rectified. The prosperity gospel is more about the bonuses offered than the biblical discipleship demanded.

In such a gospel, one handles God as one might manipulate a boss, to be sure he recognizes my plight and my worth and my situation – and compensates me accordingly. I perform this way and God rewards that way, accordingly. Such a gospel is ripe to program victimhood into the uninformed disciple, since a steady diet of words reinforces a transactional mindset. “If you send your money to us in the church, then God returns funds in multiples to you!”

Prosperity may also be sold as promises of health or power or fame. The result is the same – a sclerotic discipleship that puts my walk with Christ on a barter system with God.4

1.4. Consumer Gospel

“Consumers” are described by Hull as “self-indulgent” religious people. Disciples in this way perceive the church as a club, or perhaps merely as a service offering for their family. It fits the modern American. It is an inward focus, seeking venues, service offerings, and entertainment that maximize my enjoyment (Mitchell 2016). Discipleship in this context is about utilitarian satisfaction. Alignment with a specific community of believers, committed to setting aside personal agendas and laying down their lives is lost in the rush to catch better music, better celebrity speakers, better facilities, better children’s and adult groups, and so on. And the consumer always has options if they want to walk away.

These five gospel models mentioned above may be singular, or they may cohabit with other gospel models in the life of any one believer, in the culture of a local church, or even in a denomination. One may as easily be a Left-Prosperity Christian as a Forgiveness-Right or Consumerist disciple. Hull suggests that one, or a combination of some of these five models if advocated by a church, or held by a disciple, bodes poorly for spiritual development. Why? Each of these five models struggles when contrasted with Christ’s clear words regarding “next” for the ongoing transforming life of a Christ follower (Matt 16:24; Luke 9:23; 14:27; John 21:22).

There is a stark and compelling gospel criteria of Jesus Christ for his people, challenging anyone who has been captivated by anything short of, or partially embracing the Gospel. In passage after passage, we read Jesus’s expectations – that to be a disciple is to be invited to meet him, to evaluate him, to count the cost of coming after him, to surrender to him, to be coming (ἔρχομαι erchomai) in what Francis Schaeffer (1971, 173) calls “moment-by-moment” pursuit of Christ in death to self, and in being a bondservant, in a life that is no longer my own. Consequently, Hull concludes that these first five gospel models are not the gospel. Rather, they are hollowed-out gospel caricatures apart from the transformational work of Christ in the life of a disciple.

1.5. Gospel of the Kingdom

“Kingdom” is Hull’s final category. In Kingdom, Hull conveys his idea of a richer and more biblically contextual gospel model. Yet it too carries inherent weaknesses in the West: “Do not worry then, saying, ‘What will we eat?’ or ‘What will we drink?’ or ‘What will we wear for clothing?’ For the Gentiles eagerly seek all these things; for your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But seek first His kingdom and His righteousness, and all these things will be added to you” (Matt 6:31-33) [NASB].

Using the passage in Matthew 6, Hull’s sixth GM is defined as a Kingdom model: “followers intent on learning to live as Jesus lived.” As a single statement, there is much to appreciate in this GM. Hull describes the sixth model as a follower, shed of myopia and baggage of the prior five GMs, so it is far more exegetically sound than the prior GMs.

The word Kingdom in Western Christianity is widely ambiguous. For some Christians it is a final arrival point: I am saved, and eventually I show up at the Kingdom door. In that regard, get saved, you’re now admitted, do a few good turns now and then, and get back to your regular life. For others, it is a daily serving commitment to Christ as King and Lord. The Gospel is more than this. The Gospel, for the believer, is a recognition, a surrender, and a change in identity. A single sentence encapsulating even a rudimentary grasp of the Gospel can get long! But let’s try. When the Gospel is understood as Christ’s coming to earth as fully God and fully man, the Only-God who died for us, and specifically me, who now invites me, calls me to follow him, surrendering to his Lordship, becoming both doulos5 and adopted one, serving moment-by-moment in all the days ahead in agape relationships with all people – then we start to have a meager grasp of the Gospel. And then we encounter the incredible opportunity to be a disciple, and life going forward as a disciple… because the Gospel is the engine of discipleship.

To sub-optimize the Gospel into any other model or mode fatally caricatures discipleship. And the trends in modern Western discipling we summarize at the title 1.6 become a spiritual pandemic.

1.5.1. Challenges of Talking About the Gospel of the Kingdom

Yet through the distorting pressures of American jargon and culture a Kingdom-centric GM also wobbles. In other words, the term “Kingdom,” in the American Christian culture has become jargon. Jargon in America is an oft-used word that has lost fundamentally all original intent and meaning by users. For instance, Kingdom as a term can be misinterpreted as an earthly glory and power philosophy, such that the job of Christ’s Kingdom people is to conquer, vanquish, and compile holdings. Similarly, many American Christians would claim they are part of God’s Kingdom, and no further implications exist for a disciple as a saved Kingdom member.

Or, Kingdom thinking in America can be isolationist – just pull up the drawbridge and live inside the walls of the Kingdom, safe from contamination. For example, the monastics felt that living as Jesus lived meant isolating oneself from the world’s influence, inside his Kingdom walls. Just leave it all behind. Interestingly, many Protestant churches today produce, perhaps unwittingly, isolated individuals in a Kingdom mindset. Once they are part of the Kingdom, signified in membership with a church, their discipling tossed to them, and the kind of ongoing discipling Jesus demonstrated, is conspicuously absent. The true Kingdom followers Christ described were not to operate that way.

The fuller call of Christ to develop as disciples together is not merely intended to be accomplished in large groups or communities, but also as two or three, working closely together (Mark 6:7; Luke 9:1-5, 10:1; Deut 19:15). That biblical attribute of alongside one another, and together is largely absent today in the West, eclipsed by larger groups – church gatherings, by relatively large “small” groups, memberships, activities and so on. It is not that these are unimportant in the Gospel of Christ. But they are not the model Christ described for the life of one of his followers.

Many American churches today operate with a Kingdom of Monolithic sufficiency – in other words, do this thing and your Kingdom status is secure. One example of this single-point solution is theological. If you learn, endorse, and are articulate in this kind of theological thinking, then you’re a Kingdom disciple, and all is well. It is not to say that theology training is wrong or bad – merely that theology alone is insufficient discipleship. Discipleship cannot be reduced to orthodoxy, it must include a lived-out orthopraxy.

As we shall see in Section Two, many churches consider discipleship to be defined by their agenda of knowledge, experience, causes, or power. In these contexts, a Kingdom GM becomes a puppet of whatever emphasis.

We do not wish to generate arguments around theology and doctrine here – but we do hope to make the point that the Hull statement “followers intent on learning to live as Jesus lived” fails in one simple sense: Kingdom, in Christian-speak, is often a term of jargon in America. It has less and less defined as groups claim it as their brand, regardless of biblical integrity. Instead, we must look to the whole of Scripture to define the whole of a disciple. No single slogan suffices. The Gospel Jesus gave us requires 66 books of Scripture to lay out his GM. The true euaggelion.

1.6. Consequences or Impact of Distorted Gospel Models on USA Churches

What are the trends among disciples in the West given the deployment of these so-called gospel models? If one or more of these GMs were sufficient, shouldn’t we see the kind of disciple cultural impact and multiplication realized in the post-resurrection New Testament?

At this point, we want to list a few pertinent trends documented by major research houses on the state of the American church and ask ourselves, “Do these gospel models address these questions of impact and multiplication in these trends?”

From the Pew Research Center (2008):

Eternal life is not exclusive to Christianity, according to six out of ten Christians.

Absolute truth does not exist for 40 percent of Christians.

Talking about faith is “not my job” for 35 percent of Christians.

Demographics are not favorable among American Christians:

59 percent of millennials drop out of the church, and having kids does not bring them back (Barna Group 2014).

From 1990 to 2016, “Nones” (no religious affiliation) quadrupled from 4 percent to 17 percent (Pew Research Center 2014; Pew Research Center 2019; Smylie 2016).

“Nones” are 17 percent of the boomer generation (born 1946-1964), but for millennials (born 1981-1994) the rate more than doubles to 36 percent (Lipka 2015).

US church membership is down 17 percent from 1999 to 2016. Protestant headcount trends are down 8 percent from 2007 to 2019, and accelerating downward. And for the Roman Catholic Church, for every person who comes in, six leave (Jones 2019).

Beginning with the Gen Xr’s (born 1965-1976) most church groups have begun to shrink, a new trend compared to the two hundred preceding years (Kelley 1996, 1).

And a few citations from other respected research and survey houses:

92 percent of Christians do not believe sharing faith is important (Stark 2008).

65 percent of Christians say living out faith is better than talking about it (Barna Research 2018).

The average tithe today is 2.5 percent and declining. It was 3.3 percent during the Great Depression (NP Source).

What if a system, using that term, was designed to produce maturing disciples in the context of knowledge, lifestyle, capacity, and willingness to share the greatest of all news ever – the resurrection – but did not? And what if this system, designed to multiply these disciples, was in fact in steep decline in a church or the Church? These two rhetorical questions produce an obvious answer. Something is amiss.

Models of exemplary Western discipling – a so-called “Biblical” gospel model exist in the West too. For example, the work of Pastor Francis Chan’s “We Are Church” house church movement6 is specifically aimed at deeply intimate and developmental gatherings of a very few to serve Christ and the community as the Bible instructs. The culture of discipling triplets at Latimer Church in Beaconsfield UK7 under the leadership of Discipleship Pastor Tash Edwards likewise exemplifies the call to develop as an individual disciple, thence as pairs and small teams together, into the local and greater world to serve and make disciples that will go and make more disciples.

Let’s ask this question: If Christ gave his Church a specific mission in Matthew 28, are we staying focused on our mission? And if Christ gave us his discipleship model, why the trends described here? We now turn to the church mission statement database used in The Disciple Dilemma (Allen 2022), to better understand the consequences of these GMs and how many American churches talk about their mission.

2. Absence of Discipleship from the Mission Statements

The Hartford database of US Megachurches (Hartford Institute for Religion Research) is an electronic catalog of (most) US churches that claim to have more than 2,000 (Hence, “Mega-church”) attending via physical or online presence on any given Sunday. These megachurches have outsized leverage in Western Christian culture. The reason is that Megas in America only account for ~1 percent of the ~300,000 Protestant churches physically in operation, yet they draw over 25 percent of physical attendance on any given Sunday. Including virtual attendance in the count ups the market share concentration ratio of the Megas even more.

The criteria used in the Hartford database:

2,000 or more persons in attendance weekly, counting all worship locations.

A charismatic, authoritative senior minister

A very active 7-day week congregational community

A multitude of diverse social and outreach ministries

An intentional small group system or other structures of intimacy and accountability

The innovative and often contemporary worship format

and a complex differentiated organizational structure

There are 1,664 Protestant Mega churches listed in the database. Several other prominent Megas are not included simply because they have chosen to stay off such lists. Hartford’s work suggests they have approximately 60 percent of the Megas identified in their database, which suggests Megas in actual organizational count equal approximately 3,000 churches – or about 1 percent of total US Protestant churches.

For our research, we extracted the mission statements from 500 of the 1,664 Hartford churches listed. In some cases where no mission statement existed, we would substitute their Purpose, Vision, or Calling statements. We then produced a word cloud to extract certain keywords from those statements: Disciple, Disciples, Discipleship, Discipling, Follower, and Followers. Where one or more of those keywords were present, we listed the church as “Intending” to focus on a Gospel of discipleship. The remainder of the churches were categorized as “Unknown” regarding their perspectives on discipling.

To repeat, this word cloud review does not attempt to suggest the mere existence of words makes or breaks a culture of discipleship. But it does give us a sense of how much, or how little regard toward an intentional declaration exists in the core statements affirming a church’s culture toward discipling. Yet intentions unstated rarely produce their intended results. A culture must be shaped by its mission lest it ceases its service to a mission. To borrow a phrase from one of the business community’s organizational scholars “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”8

What follows is a summary of the research finding from our database survey of 500 megachurches in terms of keywords around discipleship in their mission statements. Here are the ten most popular “word cloud” phrases in the 500 church mission statements we reviewed:

1. Preaching Jesus Christ to all the world (22 percent)

2. Being followers of Jesus (17 percent)

3. Being a community of God’s people (13 percent)

4. Helping people believe (13 percent)

5. Showing love (11 percent)

6. A fellowship of like-minded people (10 percent)

7. Going on mission trips for the gospel (10 percent)

8. Receiving the Holy Spirit (6 percent)

9. Teaching people about Christianity (4 percent)

10. Being free (4 percent)

The notion of being a follower (a disciple) was mentioned in 21 percent (~112) of mission statements surveyed. Half (55) regarded justice, prospering, ministries, outreach, theology, global missions, and reconciliation as their primary mission, expecting disciples to result from these activities. Only two churches out of five hundred declared discipleship as their mission.

It would be interesting to sample the remaining megachurch mission statements in the Hartford database and to expand the research into sub-mega church populations as well. Yet the relatively rich sample size we have reviewed here suggests that discipleship is rare as the primary mission for American churches if it has any standing in the words at all.

Conclusion

The point of this paper is that leadership is responsible for followership. And in the arena of discipleship, contemporary leadership is not necessarily “at fault,” but is now responsible to Christ and his people for beginning a journey from an enfeebled Western discipleship. That being said, in the opening paragraphs, troublesome symptoms are emerging and accelerating in American Protestant and Evangelical communities. These trends are organizational, caused by the underlying tensions between the Kingdom-focused Gospel of Christ, and the historical traditions and societal morphing underfoot in Western Christianity.9 Because the trends are organizational, they are, by definition, a leadership issue rather than attributing deficiencies to defective individual followers of Christ. Only leadership has the authority and influence to change an organization, excluding anarchy.

To grapple with these difficulties, leaders must evaluate the connection, or the lack of connection between widely held American interpretations of the words “Gospel” (εὐαγγέλιον euaggelion) and “disciple” (μαθητής mathētēs). The traditional pressure on leaders in the Western Church is to compete, to build headcounts, capital facilities, and celebrity venues to attract ever more members. In a phrase, these attributes are entrepreneurial churches. Some of these motivations are noble: to try to help people come to know Christ. Some, however, unashamedly, exist to simply be powerful, popular, or prosperous.

These entrepreneurial pressures, in turn, distract leadership and reinforce the tendencies of Hull’s five defective GM descriptions – inducing more non-biblical thinking, and ever-more fragile disciples. Even where the sixth Gospel Model, called “Kingdom” is directly cited in church missions we find the data support a Western tendency to make experiences, prosperity, or knowledge the centerpiece of discipling. This is rather than a community of doulos serving their King by building relationships with people of all nationalities and ministering in his name.

Hull’s sixth model of the six GMs – Kingdom – generally encompasses what Christ expected of his disciples: Come and see, evaluate, surrender, learn, team, go and progress yourself and others to encounter and follow the risen Christ, because he is King and you are his bondservant. This for the rest of your life, dying to self, a doulos, daily going, daily making a way in making disciples.

The situation we describe here is not a predicted crisis coming for the Church. But it is a chronic general dysfunction in its discipleship. Leadership, pursuing entrepreneurship rather than discipleship, perilously deconstructs discipleship. Absent a reformation in mission, culture, and leadership in the Western Church, the symptoms cited above point to increasingly non-biblical discipleship. This bodes ill for the Church, because provocatively, discipleship is the cause of churches, not the other way around.