1. INTRODUCTION

Despite its seemingly rarefied standing which is buoyed by the size of its industry thought to be worth up to US $512 billion globally1, the sport industry seldom exists in a vacuum. The amount of sway held by the external environment the sport industry operates has been well documented in sport management literature.2 Among some of the external forces affecting the sport industry, over which it has no control; and to which it must adapt, are societal, political, and economic trends,3 as well as technological and geopolitical forces.4

Liberalization of international trade through Free Trade Agreements (hereafter FTAs) presents one of those external forces that can affect the sport industry5. FTAs consist of two or more countries that consent to gradually either reduce or outrightly eliminate trade barriers (tariff and non-tariff) between them, while also facilitating free trade through the unrestricted importing and exporting of goods and services between countries6 and in so doing, establishing a trade bloc known as a free trade area.7 While not a magic bullet, trade in general and free trade, in particular, can play a significant role in a country's social and structural economic transformation.8 In and of themselves, free trade areas are said to harbour a catalogue of benefits for the participating countries and regions including among others increased GDP, job creation, lower costs of doing business, investments, and technological innovation.910

Coincidentally, when factoring in the sport industry, free trade benefits tend to overlap or rather coincide with some of the salient features that drive the sport industry. According to Zhang et al., free trade in tangible and intangible resources is said to shape the sport industry by stimulating investments and technology transfers together with the free movement of people among other important sport industry-related benefits.11

The 21st century has witnessed a proliferation of FTAs, particularly in the form of regional trade agreements, which tend to amalgamate countries in the same region into one consolidated trading bloc. Currently, as of 2023, there are around 361 regional trade agreements in force that establish free trade areas around the world.12 At the same time, the sport industry is touted as being both affected and shaped by the border-transcending free flow of ideas, people, goods, and services which FTAs potentiate13 through capital investments, international movement of people as human resources, such as athletes and coaches, together with the infusion of technology in manufacturing goods, to name a few.14

Noteworthy examples of these regional FTAs include, among others, the Association for South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the European Union (EU), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), to mention a few. The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), whose trading activities began on 1 January 2021, joins the ranks among some of the existing regional FTAs in the world. In fact, with a market made up of 1.3 billion people across the 54 participating countries, it is by far the largest free trade area in the world since the formation of the World Trade Organization.15

In this light, international trade and the sport industry are a peculiar combination whose conceptual and empirical links appear not to have garnered much attention, especially in Africa in the context of the AfCFTA. Despite this lack of coverage, political and socio-economic forces, such as international trade policy agreements, can be responsible for shaping and reshaping the sport industry. By this token, the AfCFTA provides a broader framework that can allow African countries, one of which is Zimbabwe, to realize the full scope of FTA benefits for their sport industry.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. OVERVIEW OF THE AFCFTA

The African Continental Free Trade Area has been brokered through the Agreement formed between 54 of the 55 African member states, which provides a framework for the continent wide economic and regional integration through trade liberalization of both goods and services. It entered into force in 2019 based on the submission of the instrument after its ratification by the required minimum number of 24 countries, which has since increased to 47 states as of August 2023.16 To date, 47 of the 54 signatory countries (87%) have now deposited their instruments for the AfCFTA ratification with the African Union Commission Chairperson.17 The AfCFTA has the potential to advance economic, social, and cultural ties at the regional level owing to the free movement of people, capital, goods, and services.18

2.2. OVERVIEW OF THE SPORT INDUSTRY

An industry is a market where similar or closely related products or services are sold to buyers.19 It can also be defined as any grouping of businesses that have a common method of generating revenue.20 More often than not, industries tend to contribute significantly to the well-being of the societies they are a part of, as they are a lifeblood of structural and economic development, due to their ability to potentiate job creation, innovation, trade, and investment between countries.21 The sport industry is no different, and the United Nations Office on Sport for Development and Peace validates this assertion when highlighting how in every country, the sport industry is effectively part of the national industry, and therefore a major cog in socio-economic growth.22 The sport industry is therefore seen as a market whereby the products offered to its buyers are sport, fitness, recreational, and leisure-related, and it encompasses activities, goods, services, people, places, and ideas.23

The sport industry can further be divided into three sectors: the sports performance industry segment, the sports production industry segment, and the sports promotion industry segment.24 The sports performance sector includes amateur and recreational physical activities, and it extends to organized, professional high-performance sports. It is mainly made up of other management-related subindustries, for example, various professional sport event management, facility management, and sport tourism.25 The sports production sector is principally supporting as it provides the products and services needed to support the production of sports activities. In addition, it is also engaged in the trading of products in the form of goods and services that are related to sports activities and is widely regarded as forming the core of the sport industry.26 Lastly, the sports promotion segment of the sport industry includes management, marketing, finance, sponsorships, as well as business goods and services.27 It is also a segment where sport businesses are concentrated and ultimately investment and profit-oriented.

Therefore, as the sum of all individual industries or segments that produce sports products and services, including both tangible sporting goods and intangible sporting services; the sport industry brings together different factors, segments, and activities. It also aggregates a universality of stakeholders with non-aligned goals that engage within the economic relations within the field of sports.28 These stakeholders include sellers of sports products and services, users of sports information, organizers of sports events together with fans, who are consumers of sports products and information,29 companies that produce sporting products and information, the most salient being the media, sports sponsors, manufacturers of equipment, and software.30 They also include athletes, coaches, trainers, sports clubs, leagues, and federations.31

2.3. FTAs – SPORT INDUSTRY NEXUS

The liberalization of international trade through FTAs not only provides benefits of increased trade and low tariffs32 but increasingly, FTAs are now deemed to constitute key opportunities that can address some of the issues confronting the global sport industry.33 Like any other business, the sport industry must adhere to the rules and regulations of international trade. FTAs, therefore, help address issues facing the sport industry, which include, for example, issues dealing with the movement of playing talent, market access, high tariffs, unemployment, export restrictions, uniform protection of intellectual property rights, and the reform of export restrictions.34 In addition, sports goods, equipment, and products are made in different parts of the world and have to be delivered to various locations, meaning that sports manufacturers are governed by FTA rules and procedures.35

2.4. THE AFCFTA AND THE SPORT INDUSTRY

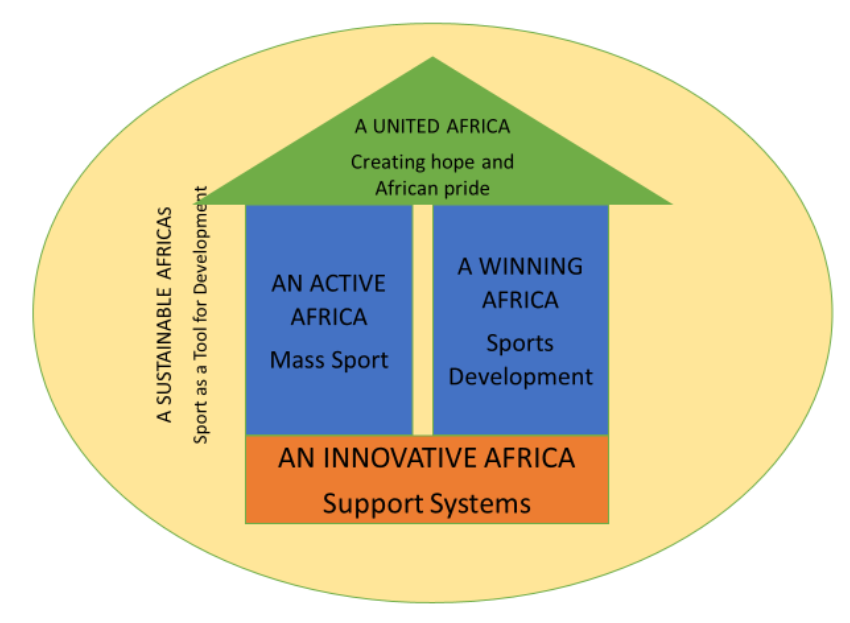

The AfCFTA is a blueprint initiative of the African Union's Agenda 2063, which, among other things, is predicated on ensuring the long-term socio-economic development of all African countries. The Agenda 2063 charts the continent along a 50-year socio-economic development trajectory. Therefore, the revised Policy for the Sustainable Development of Sport in Africa situates sport within this broader framework as sport is enmeshed along five core areas, which would see it contribute to sustainable socio-economic development36 as depicted by the diagram below.

Figure 1: The Africa We Want, the African Union37

A well-coordinated continental sports policy can contribute positively to the development of sports on the continent and the overarching priorities of the African Union (hereafter AU), such as the political, economic, and social priorities outlined in the Agenda 2063. The AfCFTA represents one of these political, economic, and socially charged policies which the AU perceives as having close synergies with Sport.38 In particular, through Sport and the Economy, a ‘Sustainable Africa’ is envisioned, and one of the activities through which the AU envisages this happening is by leveraging the AfCFTA to stimulate sports and recreation-related services and goods circulation.39

The AU Draft Policy also states several ambitions in the form of aims, objectives, and indicators that would concretize the realization of the ‘Sustainable Africa’ policy component. Coincidentally, looking at some of the benefits espoused by the AfCFTA as a stand-alone component, there appears to be a convergence between the AfCFTA benefits on the one hand, vis-à-vis the AU’s aims, activities, and indicators of socio-economic development, when it comes to realizing socio-economic development through sport, on the other hand. The extent to which they seem to overlap is articulated in the table below:

Table 1: Showing the link between general AfCFTA benefits and the AU Sport Policy outcomes

In this regard, the table shows that whereas only the AU’s goal to ‘Leverage AfCFTA to stimulate sports and recreation-related services and good circulation’ expressly includes mention of the AfCFTA, the subsequent indicators making up the independent variable ‘AfCFTA benefits’ have been arrived at by analysing primary sources such as the AfCFTA Agreement, the AU’s Agenda 2063 document, and the AU’s Sustainable Sport Policy Draft.40

2.5. POSITIONING THE STUDY

2.5.1. Trade in Zimbabwe

Trade in Zimbabwe takes place against a terrain on which the country is estimated as having the largest informal sector in Africa.41 As in many African countries, the development trajectory of Zimbabwe continues to be riddled by wider socio-economic problems akin to youth unemployment rising to above 94%,42 poor working conditions, and widespread poverty.43 In addition, the prevailing trade climate has in general put women at the forefront as they occupy between 70-80 percent of informal traders.44

2.5.2. Sport Industry Challenges in Zimbabwe

As sport and by extension the sport industry is a microcosm of wider society, the country also continues to undergo numerous challenges when it comes to its sport industry.45 The problem of a lack of investments continues to affect the Zimbabwean sport industry and impedes against development of a sporting infrastructure.46 The country faces challenges when it comes to private-sector investments in the sport industry due to a lack of incentives to attract private- sector corporations. Moreover, this is epitomized by Zimbabwe’s legislation, currently run on protectionist principles which sees sports equipment and sporting goods manufacturers facing restrictive tariff and non-tariff barriers at trading ports of entry.47

The sport industry in Zimbabwe also experiences a lack of innovation and technology whilst operating amidst a backdrop that is riddled with economic turmoil, which renders its services more or less ineffectual.48 As a result, unlike in other countries or regions, Zimbabwe has not managed to leverage its sport industry to benefit economically.49 Still, on the aspect of a lack of technology, the adoption of technology in Zimbabwe’s sport industry has remained stunted due to a lack of investments in the sport industry, lack of competence, and fear of change.50 These and other challenges that sport industry stakeholders continue to face have led to a malaise in the sport industry in Zimbabwe.51 This has compelled the Government of Zimbabwe, through its National Sport and Recreation Policy,52 together with its Vision 2030 Agenda53 to attempt to intercede by creating opportunities through the country’s sport industry and in so doing, attempt to offset a trajectory of development through the country’s sport industry.

2.5.3. Free Trade Area Economic Benefits and the Sport Industry

The European Union (both a free trade area and a Customs Union) provides a gold standard when it comes to the benefits of a free trade area for the sport industry with sport-related intra-European Union trading and extra-European Union trading with the rest of the world being said to result in over €310 billion GDP that is sport industry related.54 Free trade is also said to create sport industry-related jobs with almost 3% of employment,55 equating to 5.2 million employees in the sport industries of EU countries when mapping various stakeholder groups such as coaches, clubs, athletes, manufacturers, and federations, inter alia. In Indonesia, membership to a free trade area is said to have helped create jobs for 160,000 employees working in sportswear production for global multinational companies such as Nike.56 The creation of a free trade area has also impacted the economy in Pakistan as it accounts for a reported 300,000 to 350,000 employees in the sports goods manufacturing related small and medium enterprises (SMEs), including both skilled and unskilled laborers.57 Apart from job creation and contribution to the GDP, other economic benefits of FTAs to the sport industry include reductions in the costs of doing business, since FTAs make the business environment more open and therefore conducive for sport businesses operating in the industry.58 In addition, creation of free trade areas also helps to attract foreign investments in the sport industry.59

2.5.4. Free Trade Area Social Benefits and the Sport Industry

A significant social benefit of FTAs for the sport industry is their facilitation of the free movement of sporting talent. A notable example of a free trade area that is above and beyond in its facilitation of the movement of playing talent is the European Union (hereafter the EU),60 where the Bosman ruling inaugurated the unfettered free movement of players within the EU free trade area, as outlined in under Article 45 of the Treaty of the European Union.6162 The social benefits of FTAs to the sports industry also includes the technology component, as creation of free trade areas makes it possible to import machinery at low tariffs, which results in the increased adoption of the modern technology needed in the manufacturing of sporting goods.63 Having efficient technology improves the methods of production as well as the competitiveness of the sport industry, while also helping decrease the costs of production and subsequent cost of buying sporting goods.64 Finally, an added social benefit of free trade within the context of a free trade area is how it contributes to social inclusion in the sport industry. For instance, in the EU, men account for 54%, and women make up 46% of the gender of those employed in the sport industry.65 Furthermore, when scrutinized down to individual EU countries, such as Lithuania (60%), Finland (55%), Sweden (56%), and the Netherlands (51%), more women than men benefit from the opportunities to work in the sport industry.66 Hence, free trade contributes to social inclusion in the EU sport industry when considering that the percentage of females working in the sport industry is higher than of those employed across all other industries.67 Morestill, free trade areas also contribute to the sport industry through the social inclusion of youth segments. A point in case is in the EU sport industry, where the youth segments aged between 15-29 years make up 38% of the workforce. This is twice as much as the total employment of the youth segment across all other industries, which totals 17%.68 In fact, when taking a look at individual countries such as Cyprus and Spain, the number of young people working in the sports sector is 2.6 times higher than of those employed in the rest of the industries there.69 This aspect of social inclusion through employment appears to echo literature stating that FTAs allow the sport industry to develop along an economic foundation by driving economic growth, which in turn stimulates social development.70

2.5.5. Renouncing of FTA membership and associated Sport Industry Effects

The emergence of Britain’s opt-out from the EU in 2016 (Brexit) has steered studies to highlight the link between free trade areas and the sport industry by looking at the effects that a country’s sport industry would undergo if that particular country decided to exit the free trade area it was previously under. Before Brexit, the sport industry in the UK was heavily influenced by its membership in the EU,71 especially when it comes to its flagship brand of the English Premier League72 (EPL). Previously, the EPL could easily recruit talented players within the EU trading bloc, while only players from non-EU countries were obliged to obtain work permits.73 However, this EU-UK player mobility pathway and vice versa has been significantly curtailed due to Brexit,74 which obliges Britain to renounce all free trade benefits offered by the EU. As such, movement regulations for EU nationals to the UK have been equated to those of non-EU player, which means that European and non-European players both need to satisfy the same regulatory requirements to qualify for a work permit in the UK, which is expected to lead to fewer transfers to the EPL and other British professional sports.75

The literature on Brexit also unveils how Britain's exit from the free trade area with the EU makes its sport industry vulnerable when it comes to talented player recruitment.76 According to Article 19 of FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (2016), the international transfer of players younger than 18 years old is prohibited unless it occurs when the player transfers within the territory of the EU as this chimes with the EU’s ‘free movement of people’ principle.77 Hence, due to Brexit, British clubs are no longer able to benefit from the EU exemption of signing talented athletes aged between 16 to 18 years, which may reduce the appeal and strength of the EPL.78 This inability to attract young players can result in the decreased popularity and entertainment value of the EPL competition,79 resulting in increased financial losses of the EPL clubs – which are major stakeholders in the UK sport industry.80

Already, a dramatic fall of the pound has been witnessed following Brexit, with Humphries alleging that £1 (GBP) was worth €1.43 (EUR) in August 2015, then worth €1.26 before the referendum, but is now pegged at €1.18.81 The fall of the pound represents an 18% drop in the spending power for British teams, therefore copious amounts of literature point to the increased transfer costs being incurred by British teams paying for a foreign transfer from the rest of the EU-based leagues that operate on the EUR.82 Cumulatively, this all ties in with Cho and Kim, whose work shows that the declining value of the British pound after Brexit can financially, further affect the EPL sector of the sport industry in the UK due to a devaluation of EPL franchises and broadcasting rights, as well as higher retention costs for veteran players.83

2.6. LITERATURE GAPS AND CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE

Even though the provinces of FTAs, free trade areas and the sport industry are both thoroughly researched, in tandem they have seldom been studied together, much less in the light of developing regions such as Africa where among others, youth populations are high, unemployment is rampant, and the sport industry is not well developed, contributing only around 0.5% to the GDP.84 This is a glaring gap that is worth addressing as with so much talk about AfCFTA as an initiative geared towards promoting socio-economic development across all industries, one would be mistaken for thinking that the sport industry also prefigures among those affected industries. The existing literature, while being dominated by developed regions and countries, has till now only looked at the major sport industry benefits that accrue from the formation of FTAs. However, it seems to be silent on whether the existing macro-structural policies, such as AfCFTA, shape the expectations of sport industry stakeholders involved in the business of sport. To the authors′ knowledge, leveraging the sport industry for human and socio-economic development has not received adequate attention, particularly in the context of FTAs, which are important drivers in both, the sport industry, as well as human and socio-economic development, through their unrivalled ability to support human agency85 and human centred development via the sport industry. This paper contributes to filling this gap by examining the relationship between free trade areas and sport industry stakeholder expectations needed to provide the building blocks that can serve as a basis for planning and policymaking by the officials in the sport industry in Zimbabwe.

3. RATIONALE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Whilst AfCFTA foresees bringing about benefits in areas like manufacturing, food security, and industrialization among others, much less attention (if any) has been given to how the sport industry might find itself being affected by the benefits that the Agreement envisages. Despite being an important innovation that ties into the African continent’s socio-economic development aspirations by doing away with protectionist measures, the AfCFTA makes no direct recognition of sport even though sport engenders numerous multifaceted contributions within the socio-economic arena as it affects businesses, the economy, social development, including even governmental and intergovernmental cooperation. Moreover, FTAs have so far been underutilized by the sport industry, most times due to a lack of knowledge that the instrument exists or what is needed to fully benefit from the FTA in place, which greatly curtails the sport industry′s knowledge of the benefits a trade policy instrument like AfCFTA brings. Nevertheless, the proposed benefits of the AfCFTA that this study expects will accrue towards the sport industry will not be fully realized without the awareness and involvement of its stakeholders. According to Miragaia et al., stakeholders within the sport industry need to be kept informed and aware of the ongoing developments that occur within sports political, social, and economic environment.86

Hence, this study explored the awareness of the AfCFTA socio-economic benefits among the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe and the influence this has on their expectations. It focused on:

The awareness of the AfCFTA among the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe.

The relationship between the awareness of socio-economic benefits and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe.

3.1. THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Figure 2. Self-developed conceptual model

The following research questions were used to drive the study:

Research question 1: What is the relationship between the awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

Research question 2: What is the relationship between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

Research question 3: What is the relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

Research question 4: Is there a significant joint and composite relationship between the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders?

4. METHODOLOGICAL ASSUMPTIONS

This study is made up of certain assumptions. First, socio-economic factors (specifically free movement, technology/innovation, social inclusion, job creation, investments, increased economic growth, and decreased cost of doing business) are important Free Trade Agreement benefits. Secondly, those socio-economic factors, while not expressly mentioned in the AfCFTA in terms of their relation to sport or the sport industry, are by and large conveyed as conducing benefits and opportunities that can address some of the challenges facing the sport industry8788 as other Free Trade Agreements have been known to do. Lastly, it is assumed that awareness of the AfCFTA and of the AfCFTA′s socio-economic benefits will result in more positive sport industry stakeholder expectations, which in turn will also help in the implementation of the AfCFTA when it comes to achieving its stated benefits (specifically free movement, technology/innovation, social inclusion, job creation, investments, increased economic growth, and decreased cost of doing business). Ultimately, the assumption is that there exists a relationship between the sport industry stakeholders’their awareness of the AfCFTA, its socioeconomic benefits, and the expectations as such.

4.1. CONSTRUCTION OF INDEPENDENT VARIABLES AND THEIR OPERATIONALISATION

In collating and arriving at the independent variables, the study used awareness of the AfCFTA benefits as the Independent Variable which was then constructed into ‘the AfCFTA social benefits’ and ‘the AfCFTA economic benefits. They are further operationalised by a total of 7 indicators that highlight the AfCFTA social benefits (Free movement, Technology/Innovation, Social Inclusion) and the AfCFTA economic benefits (Investments, Job Creation, Increased Economic Growth/GDP, and Decreased costs of doing business).

The AfCFTA benefits (as they have been operationalized) derived from document reviews of multiple sources/texts. According to Andrew et al89, legal or policy research in the sport management field, which this is – requires a researcher to combine sources of authority that would be applicable to the research problem. Hence, the independent variables were arrived at by analysing primary sources such as the AfCFTA Agreement, the AU’s Agenda 2063, and the AU’s Sustainable Sport Policy Draft. Secondary sources that interpret and comment on the AfCFTA and its application, such as articles and textbooks were also used.

In addition, it is also important to note that while not labelled as the AfCFTA ‘benefits’ by the text of the Agreement itself, these indicator variables that are classified as ‘AfCFTA benefits’ are deduced primarily from the AfCFTA Agreement and other primary and secondary document reviews. For example, the AfCFTA Agreement presents the aims and objectives of the AfCFTA, which one could deduce as the AfCFTA′s benefits/opportunities as it makes sense that the aims and objectives aspired for, carry benefits.

Therefore, data sources for each of the variables can be considered as the following:

Table 2. Showing the sources of data used to construct the independent variable indicators.

| Independent Variable | Data Source |

|---|---|

|

Free Movement (constructed to encompass the free movement of goods, services, and people – as the questionnaire items under the free movement section shows) |

*The Protocol on Free Movement of Persons and Labour has always been there but has now been revived and re-purposed under the AU Agenda 2063 and the AfCFTA. |

| Technology/Innovation |

|

| Social Inclusion |

|

| Investment Creation |

|

| Job Creation |

|

| Increased Economic Growth (GDP) |

*Increased Economic Growth/GDP Increase as a benefit of the AfCFTA can also be tied to other benefits such as Investments and jobs created, which tend to be directly proportional to higher GDP |

| Decreased costs of doing business |

|

4.2. RESEARCH DESIGN

The study employed a descriptive survey research design of the correlation type. Descriptive correlational studies focus on studying the relationship between variables. A descriptive survey was employed to investigate the demography of study participants while correlations were used to study the expectations of the stakeholders in Zimbabwe’s sport industry. Keeping in mind the research objective, which was the quantification of expectations held by the sport industry stakeholders, the research made recourse to a descriptive quantitative methodology.93 Such an approach was deemed necessary in order to quantify the expectations and to undertake a statistical confirmation from the obtained results.

a) Population and sample

The population studied consisted of all sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe. The research sample included 365 people who were selected using non-probability and probability sampling. The non-probability sampling strategy was used to make a list of stakeholders based on previous studies, as well as through the input delivered by experts engaged via systematic interviewing conducted with 12 sport industry experts. Snowball sampling was then used to help account for all stakeholders using referrals pointed out by the experts. Consequently, nine categories of stakeholder groups emerged. Probability sampling was then used with a sample from the identified population being carefully selected through stratified random sampling. This was done by dividing the population (sport industry stakeholders) into different segments before randomly sampling participants stakeholders from each of the segments. By the end, the following stakeholder groups formed the study sample: CEO’s, sport coaches, sport managers, sport administrators, sport arbitrators, players, sport experts, (consultants, scientists, marketers, journalists, etc.), sporting goods/product manufacturers, and sport retailers. These needed to be in organizations registered with the SRC in Zimbabwe or in at least one sport federation, and working in the sport industry for more than two consecutive years.

b) Research Instrument

The researchers used a 43-item self-designed instrument divided into three sections: socio-demographics section, social benefits, and economic benefits sections. The Likert scale-type questions were made up of three variables that constitute the social benefits and 4 variables constituting the economic benefits of the AfCFTA. These include free movement, technology/innovation and social inclusion (social benefits), investment creation, job creation, increased economic growth, and decreased costs of business (economic benefits). The 5-point Likert scale ranged from: Very unlikely = 1, Unlikely = 2, Neither likely nor unlikely = 3, Likely = 4, to Very likely = 5, in order to examine the extent to which awareness of the social and economic benefits of the AfCFTA, contributed to the sport industry stakeholders’ expectations in Zimbabwe. A total of 430 questionnaires were distributed among sample members and 365 questionnaires were collected, indicating a response rate of 84.8 percent. To assess the validity of the questionnaire, 3 sports management lecturers were used from Ghana, Qatar, and the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. Through the test and re-test method, the Cronbach's alpha gave a reliability reading of α = 0.85 for the questionnaire.

c) Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was applied to the socio demographic information of the sport industry stakeholders in terms of frequencies and proportions using SPSS. Inferential Statistics of Pearson’s Product Moment correlation Coefficient was used on the individual variables and all other variables included in the data collection, while Multiple regression analysis was conducted with both awareness and expectations as target variables, and the social benefits (free movement, technology/innovation, social inclusion) along with the economic benefits (job creation, investments creation, increased economic growth, and decreased costs of doing business) as predictor variables. The multivariate linear regression model was applied to identify the predictor variables for sport industry expectations at a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value < 0.05 for statistically significant relationships between the independent variables with the outcome of interest.

Table 3: Decision Rule to Interpret the Mean Scores

| Mean Score | Interpretation of the Statement |

|---|---|

| 0.0 – 1.4 | Very low expectation |

| 1.5 – 2.4 | Low expectation |

| 2.5 – 3.4 | High expectation |

| 3.5 – 5.0 | Very high expectation |

Table 3 shows the decision rule to interpret the mean scores arrived at by using the weighted mean of the seven items (free movement, technology/innovation, social inclusion, job creation, investment creation, increased economic growth, and decreased cost of doing business). In this case, the weighted mean was x̅ = 3.4. The lowest score recorded across all individual Likert items (2.56) was then subtracted from the weighted mean score with results indicating 0.8, which meant the scale for the mean score began at 0.0 (Very low). Consequently, everything that fell under the lowest score of 2.5 resulted in a ‘low’ score, while everything above or equal to 2.5 received a ‘high’ score. In addition, a decision rule was again included to help further interpret the extent of the ‘high’ expectation score. Here, all means falling above or equal to the initial weighed mean of x̅ = 3.4 were further weighted to result in a weighted ‘high’ score mean of x̅ = 3.5, which implied that the expectations were interpreted as being ‘very high’ if they fell over 3.5.

d) Study variables

The awareness of African Continental Free Trade Area′s social and economic benefits are the independent variables. Sport industry-level outcomes of FTAs were considered the dependent variable, with the result of this correlation adjudged to be sport industry stakeholders’ expectations.

1. RESULTS

5.1. SUMMARY OF DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS

Table 4. Presentation of the descriptive statistics

Source: Field Data 2022

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and variance) for the awareness of the AfCFTA social and economic benefits. Under the social benefits, social inclusion scored the highest while free movement scored the least among the sport industry stakeholders. Under the economic benefits, job creation scored the highest, while the decreased cost of doing business scored the least among the sport industry stakeholders.

5.2. DEMOGRAPHIC FEATURES OF THE SPORT INDUSTRY STAKEHOLDERS

Of the 365 sport industry stakeholders selected for the study, 59.7% were male. The majority (n=75) were between 31-35 years of age (which constituted 20.5% of the total stakeholders). In total, 248 sport industry stakeholders identified themselves as being equal or younger than 40 years of age (equivalent to 67.9%), and thereby constituted the ‘youth’ demographic.

5.3. DESCRIPTION OF THE AFCFTA AWARENESS

Of the 365 sport industry stakeholders, n=287 (which constitutes 78.63% of the total stakeholders) were aware of the AfCFTA, while n=78 (which constitutes 21.37% of the total stakeholders) were unaware of the AfCFTA. However, the high levels of awareness did not appear to translate fully into similarly high levels of expectations as only n=99 (which constitutes 27.13% of total stakeholders) carried additional expectations.

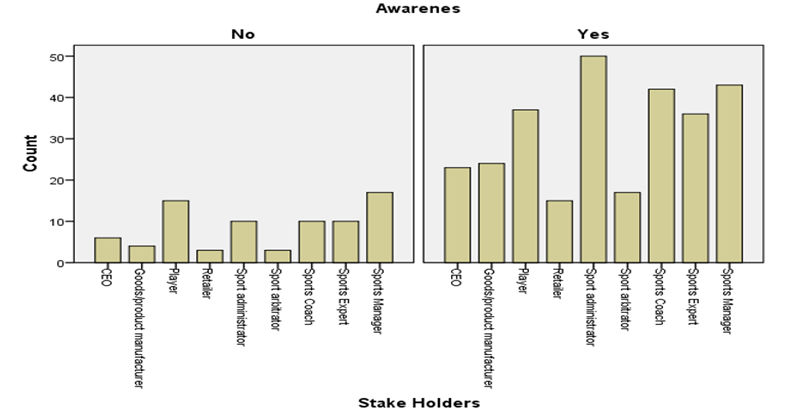

Regarding the AfCFTA awareness, the most common sources of the awareness were through social media (n=83, constituting 22.74% of total stakeholders), internal sources (n=60, constituting 16.44% of total stakeholders), TV/Radio (n=58, constituting 15.89% of total stakeholders), with newspapers and seminars both accounting for n=43 (constituting 11.78% of total stakeholders). The data further indicated the stakeholder groups holding the most awareness. As shown in the chart, sports administrators (n=50) exhibited the most awareness of the AfCFTA followed by sports managers (n=43) and sports coaches (n=42). On the other hand, sports retailers (n=15) and sports arbitrators (n=17) showcased the least awareness of the AfCFTA among the stakeholder sample chosen.

Figure 3. Bar chart representation of the number of stakeholders’ holding awareness of the AfCFTA, based on their stakeholder category.

5.4. AWARENESS OF THE AFCFTA SOCIAL BENEFITS

The awareness of the AfCFTA social benefits produced a ‘high’ grand mean (x̄) of 3.10. Out of the three social benefits items ‘free movement,’ ‘technology/innovation,’ and ‘social inclusion,’ sport industry stakeholders exhibited a ‘very high’ level of awareness on free movement (x̄ = 3.62), a ‘high’ level of awareness on technology/innovation (x̄ = 2.85), and a ‘high’ level of awareness on social inclusion (x̄ = 2.83).

5.5. AWARENESS OF THE AFCFTA ECONOMIC BENEFITS

The awareness of the AfCFTA economic benefits produced a ‘very high’ grand mean (x̄) of 3.59. Out of four economic benefits, items of ‘job creation,’ ‘investment creation,’ and ‘decreased cost of doing business,’ sport industry stakeholders recorded a ‘very high’ level of mean awareness, while a ‘high’ mean level of awareness was recorded for the economic benefit of ‘increased economic growth.’

5.6. RESULTS FROM THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Research question 1: What is the relationship between the awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

A relationship emerged between the awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders.

Table 5. Correlation analysis of the relationship between awareness of the AfCFTA and the sport industry stakeholders′ expectations

As shown in Table 5, the r-value of .622 for the relationship between awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders is significant since the p-value of .000 is less than .05 levels of significance at 363 degrees of freedom. Hence, there is a relationship between the awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders.

Research question 2: What is the relationship between the awareness of social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

A relationship emerged between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe.

Table 6. Correlation analysis of the relationship between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and sport industry stakeholders′ expectations

As shown in Table 6, the r-value of .535 for the relationship between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders is significant since the p-value of .000 is less than .05 levels of significance at 363 degrees of freedom. Hence, there is a relationship between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders.

Research question 3: What is the relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe?

A relationship emerged between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe.

Table 7. Correlation analysis of the relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and sport industry stakeholders′ expectations

As shown in Table 7, the r-value of .516 for the relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders is significant since the p-value of .000 is less than .05 levels of significance at 363 degrees of freedom. Hence, there is a relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders.

Research question 4: Is there a significant joint and composite relationship between the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders?

Table 8. Multiple regression analysis of the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders’

The result in Table 8 indicated that calculated F-value of 70.427 for the joint and composite relationship of the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders is significant since the p-value of .000 is less than .05 levels of significance at 2 and 362 degrees of freedom. Hence, there is a joint and composite relationship between the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders. The model yielded an R Square of .280 and Adjusted R Square of .276, indicating that 28% of the significance can be explained by the independent variables of the economic and social benefits of the AfCFTA on the sport industry stakeholders’ expectations in Zimbabwe.

To determine the influence of each of the predicting variables, the summary of Beta coefficient was presented in Table 9 below.

Table 9. Beta Coefficient for the Composite Relationship of the Social and Economic Benefits on the Expectations of the Sport Industry Stakeholders

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | -3.334 | 2.827 | -1.179 | .239 | |

| Social Benefits | .643 | .065 | .444 | 9.942 | .000 | |

| Economic Benefits | .394 | .066 | .264 | 5.921 | .000 | |

The results in Table 9 indicated the Beta (β) coefficient for the composite relationship of the social and economic benefits on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders. The table reveals a constant of -1.179 and calculated t-values of 9.942 for the social benefits and 5.921 for the economic benefit. The p-values for the social benefit and economic benefits were both less than .05, which is an indication that the social benefits, rather than the economic benefits, contributed significantly to the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe.

6. DISCUSSION

A high number of sport industry stakeholders indicated being aware of the AfCFTA, with social media being cited as the main source of the awareness. This can be explained by the greater importance attached to the social media by the contemporary sport industry. There is a ‘high’ level of the awareness of the social benefits and a ‘very high’ level of the awareness of the economic benefits, which contrasts sharply with previous studies by Xiaogang and Xuemei, showing a lack of awareness of FTA and free trade zone benefits by the government at a sport industry level, when it comes to developing the Yangtze River Delta under the regional free trade area there.94 The finding also digresses from PricewaterhouseCoopers who alleges that FTA benefits are unknown to sport industry stakeholders.95 Furthermore, the existence of a ‘high’ level of awareness of the social benefits and a ‘very high’ level of awareness of the economic benefits by sport industry stakeholders could be due to the wide publicity given to the AfCFTA by the Zimbabwean government, through its Ministry of Sport, Arts, and Culture, which foresees the added value of utilizing the sport industry to offset the creation of opportunities, such as jobs as outlined in Article. 256 of its Vision 2030 Agenda and in the country’s National Sport and Recreation Policy Draft.9697 Therefore, it is not inconceivable that the Ministry of Sport in Zimbabwe is active in promoting the ongoing emergent developments such as the AfCFTA, which enables it to leverage the sport industry to benefit socio-economically – something it has so far failed to do according to the findings put forward by Chiweshe.98

The results indicated that the stakeholders' ‘high’ and ‘very high’ levels of awareness did not appear to translate fully into similarly high levels of expectations. Instead, only 27.13% indicated any additional expectations. However, the additional expectations indicated the social and economic benefits of the AfCFTA including among others: the exchange in knowledge and experience of sport industry personnel, increased sponsorship, cheaper acquisition of the sports equipment and goods, cheaper cost of travel in continental competitions, and the increased attractiveness of the sport industry in Zimbabwe. This meant that stakeholders considered these additional expectations as relevant aspects and as drivers when it comes to the relationship between the AfCFTA and the sport industry in Zimbabwe.

The expectation of the AfCFTA resulting in an increased exchange of knowledge and experience of the sport industry personnel is in line with the literature by Boit attesting that one of the social benefits of FTAs for the sport industry is the promotion of cultural ties through the sport industry.99 This serves to reinforce the relative awareness of the benefit of free movement among the stakeholders and similar social benefits of increased sport industry knowledge, and experience exchanges, that have also been achieved under the ASEAN FTA, which consists of 10 countries. This has been achieved via the promotion of the national traditional sport industry aspects that are considered germane to the local customs and are created by people of all ethnic groups within the free trade area.100 Furthermore, such traditional sport industry-related events are also exported to China within the ASEAN-China FTA.101 The expectation of having an increased exchange of knowledge and experience among the sport industry personnel also corroborates findings by Jiapeng and Haichun, where the Fujian free trade zone was revealed to contribute to the deepening of the sport industry linkages between China’s Fujian provinces and the sport industries in Taiwan.102

In addition, an additional expectation among the sport industry stakeholders is to have cheaper travel costs in continental competitions. This is in harmony with the findings from the EU by Parrish and McArdle stating that the EU single market helped revolutionize the freedom of movement among coaches and athletes by facilitating free movement of sports personnel.103 The expectation also dovetails with the literature findings by Saberi et al., to the effect that the free trade zone in Iran has benefited the sport industry, thereby making it easier to recruit sport professionals, such as coaches, and to attract tourists due to facilitation of the ease in free movement.104 Thus, this also confirms the high awareness of the free movement benefit of the AfCFTA in reference to others, as it can increase free movement in areas such as sports tourism and free movement of goods, as well as tangible and intangible services. Therefore, this could signal the value stakeholders attach on free movement, which can enhance the social capital of youth entrepreneurs and their employability through networking and acquisition of sport industry training and experience.

Furthermore, some other expectations by sport industry stakeholders include cheaper acquisition of sports equipment and goods. This is an expectation that appears to coalesce with the existing literature by Moyo which identifies protectionist trade measures in Zimbabwe as a challenge for the sport industry there due to the restrictive tariff and non-tariff barriers that sports equipment and sporting goods manufacturers in Zimbabwe face when importing goods.105 Moreover, there is also the expectation that AfCFTA will increase the attractiveness of sport in Zimbabwe. This also ties into the literature that looks at the challenges faced by the sport industry in Africa, which are outlined in previous studies. For instance, the lack of technology is a factor that influences the unpopularity and unattractiveness of the African sport industry within the African market. This lack of attractiveness of the sport industry in Africa is also established by Zhang et al., who point out that sport consumers in Africa appear to favour global sport teams, leagues, and sporting products over the same locally manufactured products.106

Our results from research question 1 confirmed the relationship between the awareness of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe. These findings chime with theoretical literature by Hargitai that demonstrates that sport stakeholders exhibit more interested expectations towards the political and social developments, such as trade that is likely to affect sports business in economic terms.107 It also conflates with the literature by Thormann and Wicker outlining that the stakeholders with more awareness tended to exhibit more positive expectations of how Major Sports Organizations ought to respond to COVID-19. From an empirical perspective, both the high positive relationship and the significant relationship between the awareness and expectations is also analogous to the literature that foresees FTAs to potentiate numerous improvements when introduced within the African sport industry context.108 Boit further outlines several areas that a regional FTA is anticipated to proffer for the sport industry in Africa, including aspects such as improved trade and technology, better sports infrastructure, and better sport competition standards among others.109 This is not to add to other more general expectations, such as the realization of increased sport industry sales and profits,110 which probably can become more concrete and varied once more in-depth awareness of the AfCFTA has been created.

The second research question confirmed a relationship between the awareness of the social benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe. Of these, social inclusion showed a higher mean compared to both, free movement, and technology/innovation. Considering the emerging developments in Zimbabwe where high levels of unemployment exist among the youth,111 wider social realities as these may compel the sport industry′s stakeholders to place a very high rating on social inclusion, especially if it is conceived as a means of enhancing the acquisition of sport industry training and experience for the youths. This falls in line with the theoretical literature by Babiak and Kihl, extending the view that sport industry stakeholders′ expectations become more sustained when activities impact upon youth development.112 Moreover, it also resonates with European literature citing from the EU, stating that sport has facilitated the employability of up to 38% youths in its sector.113 Therefore, in the case of the youth in Zimbabwe, it is likely that social inclusion informs the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders, given that the youths are believed to have the skills and capacities required to drive entrepreneurial sport innovations that can be traded to generate earnings and support the local industry production processes. These processes include manufacturing, supplies, and sales while building regional value chains via trade in locally manufactured products that can be used to grow Zimbabwe’s sport industry.

The third research question confirmed a relationship between the awareness of the economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe. Of the four economic benefits, job creation had the highest rating followed by investment creation. Increased economic growth and decreased cost of doing business had the least, but equal in terms of mean ratings. The reason for both findings could be that the majority of sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe conceive that the AfCFTA will have similar benefits to that of the EU free trade area, which provides a golden standard when it comes to the benefits of a free trade area for the sport industry. This would tally with the European Commission′s outline that the EU trading bloc has helped create numerous sport industry-related jobs,114 which account for up to 3% of the employment in the trading bloc, translating to around 5.2 million people. In addition, this benefit also encompasses the EU FTAs with other countries such as Indonesia.115 FTAs have also helped create up to 160,000 sport industry-related jobs in India116 and up to over 300,000 in Pakistan, whose sport industry absorbs both skilled and unskilled workers.117

Lastly, the fourth research question yielded that the social benefits had a significant relative influence on the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders, which implies that the social benefits contributed more to the stakeholders′ expectations than did the economic benefits. In general, it is the economic benefits of FTAs that have been said to be more salient when it comes to the sport industry. For instance, Xiaogang and Xuemei outline the relative importance attached to economic benefits of the Yangtze free trade zone as it bolsters the economic security of the sport industry there.118 Also, Jiapeng and Haichun highlight the relative importance of economic benefits in the literature on free trade zone in China, with cost reduction in particular identified as being the biggest benefit.119 This relative importance of economic benefits is also reflected by Garcia120 and Humphries121 who inadvertently highlight the relative importance of economic benefits when outlining the economic destabilization encountered with Britain′s exit from the EU free trade area.

This importance attached to the social benefits is even more striking given that the economic terrain in Zimbabwe is characterized by up to as much as 94% unemployment, with most of the employees belonging to the informal sector.122 Hence, it is significant that the sport industry stakeholders in Zimbabwe do not attach more significance to the economic benefits when notifying their expectations given the country′s overall lack of employment. In the Zimbabwean context, the reason for the social benefits to have a relatively significant influence on the stakeholders′ expectations could be because Zimbabwe’s economic development dwarfs in comparison to the level of economic development that characterizes the other countries so far studied. It is feasible that the social benefits weigh more on stakeholders’ expectations because of the extent to which the social and economic benefits, themselves, are interlinked. For example, social benefits such as free movement, social inclusion, and technology/innovation seem to also all cater to economic benefits, such as job creation and decreased costs of doing business, among others, as they entail human resources-centred aspects to bring about socio-economic inclusion. This reasoning resonates with findings by Nawaz et al. on free trade area creation in Pakistan resulting in the subsequent influx of technology required to manufacture sporting goods,123 which has had a hand in helping decrease not only the costs of production but also the cost of buying sporting goods there.124 Also, a report from Eurostat on the EU trading bloc contributing to social inclusion through the employment of more women than men in the sports industries of Lithuania, Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands can also be taken into account, alongside contributing to social inclusion through increasing employability of youths in the sports sector by up to 35%.125

7. CONCLUSION

This study focused on the role awareness of the AfCFTA socio-economic benefits in predicting the expectations among the sport industry stakeholders within the context of both sport industry challenges and an increasingly fractured socio-economic development trajectory in Zimbabwe. The awareness of the social and economic benefits of the AfCFTA were shown as significant correlates or drivers in the formation of the sport industry’s expectations. Based on the findings of this study, it is further concluded that the socio-economic benefits of the AfCFTA and the awareness of these benefits significantly influenced the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders. This finding reinforces the importance of awareness-raising initiatives on the AfCFTA by the Zimbabwean government with respect to acknowledging the applicability of its socio-economic benefits towards the current challenges within the sport industry. It was also confirmed that from the social and economic benefits, it was the social benefits that contributed more to the expectations of the sport industry stakeholders since the AfCFTA social benefits had a significant relative influence than the economic benefits did.

Moreover, the findings also serve to highlight the social development potential the sport industry has, when interacting with the AfCFTA. In this regard, when the sport industry interacts with the AfCFTA, it brings about human agency that can support the activities and participation of the key human resources demographics, such as sport industry youth entrepreneurs. Given that the facilitation of youth agency is an important strategy that can combat seismic unemployment rates, the relationship between the AfCFTA socio-economic benefits and the sport industry expectations is important since the youth have a high affinity for sport and the entrepreneurial capacity necessary to drive the sport industry innovations needed, to take advantage of the opportunities bequeathed by the AfCFTA socio-economic benefits. It is in this regard that the demographic dividend in Zimbabwe arguably lies in its youth. Therefore, the Zimbabwean government would do well to capitalize upon this dividend by adopting a holistic approach that takes cognizance of wider socio-economic issues while embracing the AfCFTA’s ability to stimulate the human agency of the youth groups operating in the country’s sport industry, which can help tackle these wider socio-economic challenges. For instance, given that the high representation of the stakeholders in the research is under the age of 40 and therefore considered as youths, more ownership of the sport industry governance should be in the hands of those who occupy the largest stake and have the nous to develop the sector further when presented with the socio-economic benefits the AfCFTA brings.

8. THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This research has succeeded in bridging two concepts seldom studied together, one being trade, which is a form of public policy, and the other being the sport industry. The main contribution it conveys therefore is that the sport industry does not exist in a vacuum, but rather, it is affected by and in turn affects its external environment. The links between the sport industry vis-à-vis structural policies existing outside the sport industry’s immediate remit (such as the AfCFTA) and the resultant stakeholder expectations is an underexplored area in sport management research. The study filled this gap by exploring the link between the sport industry and the external concept of the AfCFTA. From a sports managerial standpoint, the study’s results provide a deeper understanding of the contribution of the AfCFTA social and economic-related benefits to the sport industry stakeholders′ expectations. Consequently, there is a need to create more awareness about the AfCFTA to enable sport industry stakeholders to form even more expectations about how they can benefit by leveraging these AfCFTA socio-economic benefits in addressing the already existent sport industry-related challenges that they appear to have grasped more fully. The onus, therefore, lies on the Zimbabwean government, through its sport ministry, to educate various stakeholder groups (such as local sport industry stakeholders and owners of sports businesses SMEs) on the bespoke benefits of the AfCFTA, hereby allowing them to leverage all the opportunities by using them to their advantage.

Also, as research on the development of the AfCFTA and the sport industry is in its infancy, it is important for Zimbabwe’s sport ministry to construct suitable communication plans that strengthen and increase the publicity of how the AfCFTA is not a stand-alone component independent of the sport industry, but can both benefit the sport industry and address its challenges. An additional policy implication of the study is that it provides preliminary findings that can help sport industry stakeholders’ to lobby the Zimbabwean Ministry of Sport for the inclusion of the AfCFTA in the current and future sport policymaking on the one hand, while also enabling African governments – including that of Zimbabwe, to lobby the African Union for the inclusion of a sport-related protocol in the text of the AfCFTA document in order to enable the sport industry to gain recognition as AfCFTA ‘stakeholders’ by having the sport policy lever added to the AfCFTA Agreement itself, on the other hand. Apart from its very practical policy contributions, the study also contributes to the body of literature on the range of socioeconomic value chains that the sport industry helps to create when allowed to combine with free trade.

9. LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

Due to a dearth of empirical literature highlighting the nexus between FTAs, free trade areas and the sport industry, the study also made use of the literature looking at Free Trade Zones126 and the sport industry, which can count as a limitation. The literature conveys different benefits that are carried by FTAs, but this study limited itself to only 7 variables falling under the construct of the AfCFTA social and economic benefits – further studies, if done, could reveal more. The study also focused on the sport industry in Zimbabwe, but the relationships between constructs may differ between countries, which means that its results may be difficult to generalize when including other African countries. Consequently, it would be interesting to conduct similar studies on sport industry stakeholders′ awareness and expectations of the AfCFTA in other contexts apart from Zimbabwe since the AfCFTA is binding to 54 African countries. Finally, since trade implies two or more countries engaged in an exchange relationship, future studies can adopt comparative approaches to sport industry stakeholder expectations on the AfCFTA to discover whether a gap in expectations exists.

Bibliography

20. Eurostat. Employment in sport in the EU. 2019. Accessed September 15, 2022.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Employment_in_sport.

21. Eurostat. Employment in sport. 2021. Accessed May 10, 2022.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Employment_in_sport.

24. Galkin Victor. Sports economics and sports business. Moscow: KNORUS, 2006.

25. Garcia, Borja. Will Brexit break up the Premier League? UK In A Changing Europe. 2018. Accessed April 5, 2022.https://ukandeu.ac.uk/will-brexit-break-up-the-premier-league/.