License (open-access, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/):

CC-BY-SA

License (open-access):

Prava korištenja: CC-BY-SA

License (open-access):

Journal content is published under CC-BY-SA licence.

Publication date: 2022

Volume: 22

Issue: 39

Vijest

Nautical Charts – Meeting of Science, Art and Practice

Josip Faričić

; Sveučilište u Zadru, Odjel za geografiju

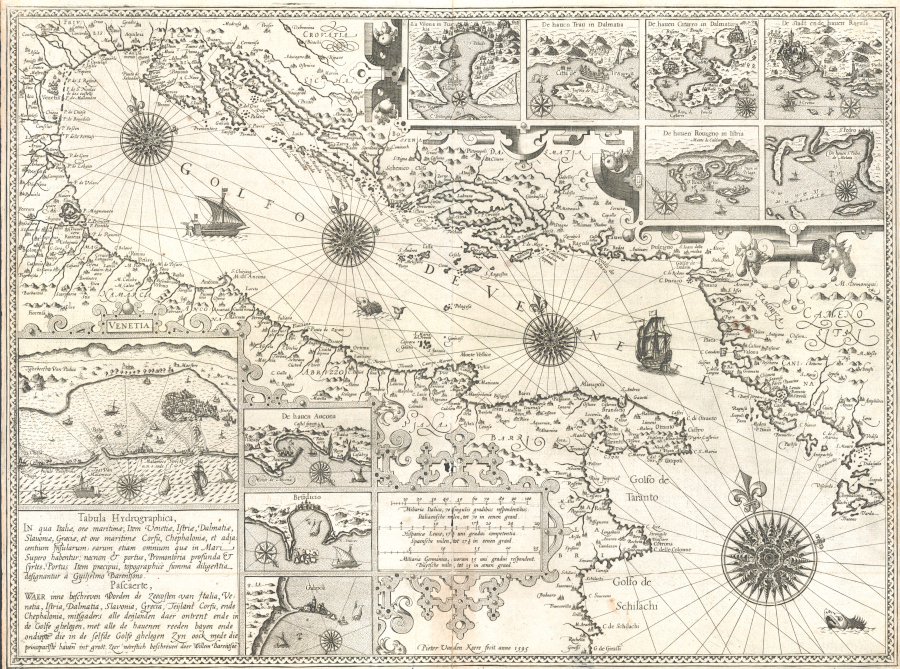

An exhibition entitled Sea Charts – Meeting of Science, Art and Practice was held in Zadar from 10−17 March 2023. The exhibition was realised on the basis of research within the scientific project Early Modern Nautical Charts of the Adriatic Sea: Source of Knowledge, Means of Navigation and Media of Communication, funded by the Croatian Science Foundation and organised within the project Reconnect Science with the Blue Society − Blue Connect, co-funded by the European Union.

306272

28.4.2023.

![]()

Posjeta: 653 *

Exhibition, School Ship Kraljica mora (Queen of the Sea), Zadar 10-17 March 2023

An exhibition entitled Sea Charts – Meeting of Science, Art and Practice was held in Zadar from 10−17 March 2023. The exhibition was realised on the basis of research within the scientific project Early Modern Nautical Charts of the Adriatic Sea: Source of Knowledge, Means of Navigation and Media of Communication, funded by the Croatian Science Foundation and organised within the project Reconnect Science with the Blue Society − Blue Connect, co-funded by the European Union.

The exhibition attracted great interest from the public and was also accompanied by media coverage, for example in the show The Sea on the first channel of Croatian television. This interest can be justified by the great importance of nautical charts for planning and carrying out various navigation tasks and, at the same time, by the value of this type of map as a valuable source of spatial data on the coast, islands and the associated maritime area. The attractiveness of the exhibition was also contributed to by the location of the exhibition – the lounge in the school ship Kraljica mora (Eng. Queen of the Sea), which is used by students of all Croatian secondary maritime schools and students of all Croatian universities where they study nautical and marine engineering and related studies.

Due to its geographical location and the importance of the Adriatic Sea in the socio-economic system of the Mediterranean, this sea and its coastal area have been the scene of numerous contacts and exchanges of goods, ideas and technologies since ancient times. An important catalyst for spatial interactions affecting spatial organisation, economic and cultural development and the interpenetration of economic and demographic structures in the Adriatic is shipping. In the form of various components (navigation, shipping, shipbuilding, port activities, fishing, etc.), it is based on the application of various sources of knowledge, means and technologies, among which nautical charts occupy a special place. Nautical charts, now mostly in digital form and as an integral part of electronic navigation systems, are the legacy of a long tradition of maritime links with other scientific disciplines and keep pace with the development of technologies. Therefore, they form an important part of maritime culture.

From the end of the 13th century at the latest, nautical charts became an indispensable means of navigation and, like many other types of maps, a diverse medium of communication. Mediaeval nautical charts were related in content to navigational manuals (portolans), so they are also called portolan charts, and given the network of rhumbs (straight lines spread radially from the wind roses and compass roses that cover the field of these charts) that corresponded to the system division of a full circle into 16 or 32 directions, the name compass map was also used for them. From then until today, nautical charts have been a necessary complementary source of spatial data, alongside navigation manuals, for seafarers, but also for many others interested in coastal areas and related marine areas, for people who need this knowledge for education and research, and for people who carry out their economic and social activities in these areas.

Previous research on nautical charts has shown that these charts have long been ahead of geographical and other types of charts in the past because of their quality in terms of mathematical basis and accuracy of geographical content. This is due to the fact that seafarers needed high-quality data on the geographical features of the area they were navigating in order to be able to organise precise and safe navigation. This need obviously provided the impetus for the mapping of the Mediterranean very early on, which had to fulfil two important conditions – accuracy and efficiency, i.e. a precise solution to basic navigational tasks. After all, seafarers could not freely interpret or rely on their subjective perception of geographical reality. Orientation and navigation at sea are much more uncertain than orientation and movement on land. Seafarers are dependent on various natural factors (winds and waves, ocean currents and tides, nature of the seabed) and the manoeuvrability of ships, even when sailing in familiar waters, whereas a traveller on land can much more easily avoid a natural or other danger and seek shelter in time. The fog of uncertainty faced by seafarers could only be dispelled by the accurate determination of geographical coordinates and navigational course, the measurement of sea depths and navigational speed, which meant having the skill of astronomical and terrestrial navigation, which required a skilful use of compasses, various astronomical instruments and nautical charts.

At the same time, cartographic production reflected the quality of the spatial data, the geographical and cartographic competence of the author (including drawing skills), but also the political attitudes and ideas as well as the general cultural characteristics of the era in which it took place. It was also influenced by the development of technology, with a major change occurring when nautical charts drawn on parchment were gradually replaced from the 16th century onwards by printed nautical charts on paper – cheaper and more easily available in larger numbers. The basic content of the nautical charts was intended for seafarers and therefore focused on a narrow coastal strip with land and islands and the associated water area. However, the content of the nautical charts was supplemented by ornamentation very early on, because wealthy customers were also interested in nautical charts – members of the social elite, for whom cartographers produced artistically designed graphic representations of the coastal and marine areas with many symbolic ornaments (e.g. rose compasses with a lily flower as a sign for the north and the cross as a sign for the east). The needs and requirements of the various users went beyond utilitarianism, resulting in nautical charts becoming complex achievements of science, art and navigational practise.

In addition to seafarers, ship owners and merchants were particularly interested in nautical charts, wanting an insight into the maritime space in which shipping took place and on which their business depended. Military and political structures were also interested in this cartographic genre, as they needed to determine the location and spatial relationships between strategically important geographical objects (islands, ports, capes) in order to plan and carry out various activities on a strategic and operational level. In this context, it is worth highlighting the Republic of Venice, which established itself as the leading political and economic power in the Adriatic. These state interests were depicted directly on the nautical charts by the Venetian cartographers. For example, they called the entire Adriatic the Gulf of Venice (Ital. Golfo di Venezia). This name, which uncritically reflected the contents of the Venetian nautical charts, was adopted by other European cartographers, which was not necessarily related to the attribution of the entire Adriatic to Venice.

Although some patterns (especially regarding the representation of the coastline and islands) were maintained for centuries, slowing down the initial momentum in the development of maritime cartography of the Adriatic, improvements were gradually achieved in the quality of the collection, processing and visualisation of data on sea depths, types of seabed, sea currents, tides, magnetic declination, ports, etc. The organisation of comprehensive geodetic and hydrographic surveys and institutionalisation, i.e. the takeover of cartographic activities from individuals by the state and the establishment of military geographic and hydrographic institutes, significantly changed maritime cartography. With the first modern nautical charts that emerged as a result of these surveys at the beginning of the 19th century, seafarers obtained very reliable cartographic aids that contributed to the efficiency and safety of navigation. Of course, the efficiency and safety of navigation depend heavily on experience, i.e. knowledge of local geomorphological, oceanographic and climatic conditions, which has been accumulated and updated over the centuries. Even today, with the application of the latest IT technologies, including satellite systems for orientation and navigation, this is necessary in terrestrial navigation.

List of nautical charts in the exhibition / Popis pomorskih karata na izložbi

Pietro Vesconte, [Nautical Chart of the Adriatic Sea], Venice, 1318 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek / Austrian National Library, Vienna, Call number: Cod. 594 (Cimel. 20), 10v-11)

Bartolommeo Zamberti (dalli Sonetti), [Nautical chart of the Adriatic Sea], Venice, 1485 (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London; Call number: P/21(2); MS 38-9920C)

Pîrî Reis, [Nautical chart of the Adriatic Sea], in: Kitab-i bahriye, Gallipoli, 1526. (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; Call number: W.658, fol. 208a)

Antonio Millo, [Nautical map of the Adriatic Sea], Venice, 1583 (Biblioteka Narodowa / National Library of Poland, Warsaw; Call number: BN ZZK 0.2399)

Willem Barents, Tabvla Sinvs Venetici, Amsterdam, 1595. (Stanford University Libraries, Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford)

Vincentius Demetrius Voltius (Vicko Dimitrije Volčić), Golfo di Venetia, Naples, 1593. (Kansalliskirjasto / National Library of Finland, Maps, The Nordenskiöld Map Collection, Helsinki; Call number: N-Kt-103c)

Jean François Roussin, Carta du Golfo di Venetia, Venice, 1661. (The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, Library Collections, Maps and Atlases, Portolans, San Marino, CA, USA; Call number: mssHM 37)

Lodovico Furlanetto, Nuova carta Marittima del Golfo di Venezia, Venice, 1784 (State Archives in Zadar, Cartographic Collection, Zadar; Call number: HR-DAZD -383, no. 3.1)

Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré, Reconnoisance hydrographique du Detroit de Pasman, in: Reconnoisance hydrographique des ports du Royaume d'Italie situes sur les cotes du Golphe de Venise commence en 1806, Paris, 1806. (National and University Library, Collection of Maps and Atlases, Zagreb; Call number: A III -S18-9)

Vincenzo de Lucio, Nuova carta del Mare Adriatico ossia Golfo di Venezia, Trieste, 1809. (Scientific Library of Zadar, Zadar; Call number: 15188 D-20)

Military Geographical Institute, Carta di cabotaggio del Mare Adriatico (sheet VII), Milan, 1822 - 1824 (State Archives in Zadar, Cartographic Collection, Zadar; Call number: HR-DAZD -383, no. 3.2)

K. K. Kriges Marine, Inseln Grossa und Incoronata, Trieste, 1872 (State Archives in Zadar, Borelli Galbiani family, Zadar; Call number: HR-DAZD -348, Box 6, Ž, No. 16)

Croatian Hydrographic Institute, Adriatic Sea (general nautical chart at scale 1:800,000), Split, 2011.

Croatian Hydrographic Institute, Šibenik Channel (nautical plan at scale 1:25,000), Split, 2015.

Izložba, Školski brod Kraljica mora, Zadar, 10–17. ožujka 2023.

U Zadru je od 10 do 17. ožujka 2023. priređena izložba Pomorske karte – susret znanosti, umjetnosti i prakse. Izložba je ostvarena na temelju istraživanja provedenih u sklopu znanstvenog projekta Ranonovovjekovne pomorske karte Jadranskog mora: izvor spoznaja, sredstvo navigacije i medij komunikacije koji financira Hrvatska zaklada za znanost, a organizirana je kao jedna od aktivnosti projekta Reconnect Science with the Blue Society – Blue Connect sufnanciranog sredstvima Europske Unije.

Izložba je pobudila velik interes u javnosti, a popraćena je i medijskim objavama, primjerice u emisiji More na Prvom programu Hrvatske televizije. Taj interes može se opravdati velikom važnošću pomorskih karata za planiranje i provedbu različitih navigacijskih zadaća, a ujedno i vrijednošću te vrste karata kao dragocjenog izvora prostornih podataka o obali, otocima i pripadajućem maritoriju. Atraktivnosti izložbe pridonijelo je i mjesto izložbe – salon u školskom brodu Kraljica mora koji koriste učenici svih hrvatskih srednjih pomorskih škola i studenti svih hrvatskih visokoškolskih ustanova na kojima se studiraju nautika i brodostrojarstvo te srodni studiji.

S obzirom na geografski položaj i važnost Jadrana u društveno-gospodarskom sustavu Sredozemlja, taj je morski i pripadajući obalni prostor još od staroga vijeka poprište višestrukih dodira te razmjene dobara, ideja i tehnologija. Važan katalizator prostornih interakcija koje utječu na prostornu organizaciju, ekonomski i kulturni razvoj te prožimanja gospodarskih i demografskih struktura na Jadranu je pomorstvo. Ono se u vidu različitih sastavnica (navigacija, brodarstvo, brodogradnja, lučke aktivnosti, ribarstvo i dr.) zasniva na primjeni različitih izvora znanja, te sredstava i tehnologija, među kojima posebno mjesto imaju pomorske karte. Pomorske karte, danas uglavnom u digitalnom obliku i kao sastavni dio elektroničkih navigacijskih sustava, baštine dugu tradiciju veza pomorstva s drugim znanstvenim disciplinama i hoda u korak s razvojem tehnologija. Stoga čine važnu sastavnicu maritimne kulture.

Pomorske karte su najkasnije od kraja 13. st. postale nezaobilazno sredstvo navigacije i, poput mnogih drugih vrsta karata, višestruki medij komunikacije. Srednjovjekovne su pomorske karte sadržajno bile povezane uz plovidbene priručnike (portulane) pa se još nazivaju i portulanske karte, a s obzirom na mrežu rumba (ravnih crta koje se zrakasto šire iz ruža vjetrova i kompasnih ruža kojim je prekriveno polje tih karata) koja je odgovarala sustavu podjele punog kruga na 16 ili na 32 smjera, za njih se koristio i naziv kompasne karte. Od tada pa sve do danas pomorske su karte uz plovidbene priručnike (peljare) neophodan komplementaran izvor prostornih podataka pomorcima ali i mnogim drugima koje zanimaju obalna i pripadajuća morska područja, osobama kojima su ta znanja potrebna za obrazovanje i istraživanje i osobama koji svoje gospodarske i društvene aktivnosti provode u tim područjima.

Dosadašnjim istraživanjima pomorskih karata utvrđeno je da su tijekom prošlosti te karte svojom kvalitetom u pogledu matematičke osnove i točnosti geografskog sadržaja dugo prednjačile u odnosu na geografske i druge vrste karata. To je povezano uz činjenicu da su pomorcima trebali kvalitetni podatci o geografskim obilježjima prostora kojim su plovili da bi mogli organizirati preciznu i sigurnu plovidbu pa je ta potreba očito vrlo rano potakla kartiranje Sredozemnog mora koje je trebalo ispuniti dva važna uvjeta –egzaktnost i efikasnost, tj. precizno rješavanje osnovnih navigacijskih zadataka. Pomorci se, naime, nisu mogli prepustiti slobodnoj interpretaciji niti ovisiti o subjektivnoj percepciji geografske stvarnosti. Orijentacija i navigacija na moru mnogo su neizvjesnije od orijentacije i kretanja na kopnu. Pomorci ovise o različitim prirodnim čimbenicima (vjetrovima i valovima, morskim strujama i morskim mijenama, obilježjima morskoga dna) i manevarskim mogućnostima brodova čak i pri plovidbi u dobro poznatom akvatoriju, dok putnik na kopnu može mnogo lakše izbjeći prirodnu ili neku drugu opasnost te pravodobno potražiti zaklonište. Magle neizvjesnosti s kojom su se susretali pomorci mogla se raspršiti jedino preciznim utvrđivanjem geografskih koordinata i kursa plovidbe, mjerenjem dubina mora i brzine plovidbe, što je značilo da je trebalo imati vještinu astronomske i terestričke navigacije koje podrazumijevaju umješno korištenje kompasa, različitih astronomskih instrumenata i pomorskih karata.

Kartografska je produkcija istodobno odražavala kvalitetu prostornih podataka, geografske i kartografske kompetencije autora (uključujući crtačko umijeće), ali i političke stavove te ideje i opća kulturna obilježja epohe u kojoj se zbivala. Također, na nju je utjecao razvoj tehnologije pri čemu je velika promjena nastupila kada su pomorske karte crtane na pergameni od 16. st. postupno zamijenjene tiskanim – jeftinijim te lakše i u većem broju primjeraka dostupnim – kartama na papiru. Osnovni je sadržaj pomorskih karata bio namijenjen pomorcima i stoga fokusiran na uski obalni pojas kopna i otoka s pripadajućim akvatorijem. Međutim, sadržaj pomorskih karata vrlo rano je dopunjavan dekoracijama jer su za pomorske karte bili zainteresirani i bogati naručitelji – pripadnici društvenih elita za koje su kartografi pripremali umjetnički oblikovane grafičke prikaze obalnoga i morskog prostora s mnoštvom ukrasa bogate simbolike (npr. kompase ruže s ljiljanovim cvijetom kao znakom sjevera i križem kao znakom istoka). Potrebe i zahtjevi različitih korisnika nadilazili su utilitarnost što je rezultiralo činjenicom da su pomorske karte postale kompleksna ostvarenja znanosti, umjetnosti i plovidbene prakse.

Uz pomorce, za pomorske su karte najviše bili zainteresirani brodovlasnici i trgovci koji su htjeli imati uvid u maritimni prostor u kojem se zbivala plovidba o kojoj je ovisilo njihovo poslovanje. Za taj kartografski žanr bile su zainteresirane i vojne te političke strukture koje su imale potrebu utvrditi lokaciju i prostorne odnose među strateški važnim geografskim objektima (otocima, lukama, rtovima) radi planiranja i provedbe različitih aktivnosti na strateškoj i operativnoj razini. U tom kontekstu potrebno je istaknuti Mletačku Republiku koja se nametala kao vodeća politička i ekonomska sila na Jadranu. Takve državne interese mletački su kartografi izravno demonstrirali na pomorskim kartama. Primjerice, cijelo Jadransko more imenovali su Mletačkim zaljevom (Golfo di Venezia). To su ime, nekritički reproducirajući sadržaj mletačkih pomorskih karata, preuzimali i drugi europski kartografi, što nije bilo nužno povezano s njihovom atribucijom cijeloga Jadrana Veneciji.

Premda su neki obrasci (posebno u pogledu prikaza obalne crte i otoka) zadržani stoljećima, što je usporilo početnu dinamiku u razvoju pomorske kartografije Jadrana, postupno su postignuta unaprjeđenja u kvaliteti prikupljanja, obrade i vizualizacije podataka o dubinama mora, vrsti morskog dna, morskim strujama, morskim mijenama magnetskoj deklinaciji, lukama i dr. Pomorska kartografija umnogome je promijenjena organizacijom sveobuhvatnih geodetskih i hidrografskih izmjera te institucionalizacijom, odnosno državnim preuzimanjem kartografskih aktivnosti od pojedinaca te osnivanjem vojno-geografskih i hidrografskih instituta. S prvim modernim kartama koje su nastale kao rezultat tih izmjera početkom 19. st. pomorci su dobili vrlo pouzdana kartografska sredstva koja su pridonosila učinkovitosti i sigurnosti plovidbe. Naravno, učinkovitost i sigurnost plovidbe ovise umnogome i o iskustvu, odnosno poznavanju lokalnih geomorfoloških, oceanografskih i klimatskih značajki koje je akumulirano i ažurirano stoljećima. Ono je i danas, uz primjenu najnovijih informatičkih tehnologija, uključujući satelitske sustave za orijentaciju i navigaciju, nužno u terestričkoj navigaciji.