1. Introduction

We said that the American cinema pleases us, and its filmmakers are slaves; what if they were freed? And from the moment that they were freed, they made shitty films.

François Truffaut1

Consider the following item of folk wisdom on the arts: the degree of creative freedom enjoyed by an artist is a function of their freedom from constraint; an idea which might derive from the same principle applied to freedom (of thought, of expression, of action) more generally. “Prima facie it would seem that nobody could have a motivation for discarding options”, writes Jon Elster.

Most people would rather have more money than less, more occupational options rather than fewer, rewards sooner rather than later, a larger range of potential marriage partners rather than a smaller one, and so on. (Elster 2000, 1)

Advocates of free jazz, free improvisation, and free verse seem to have embraced the principle fully, freeing themselves of some of the most traditional constraints in music and poetry respectively. Not all folk wisdom is misleading; it isn’t called “wisdom” for nothing. And indeed we will find that there are reasons why this particular folk belief is widely held. Nonetheless it is, I shall argue, at best misleading, and a very different conception of the relationship between artistic freedom and constraint is more plausible.

2. Conventions and other varieties of constraint

What could be more obviously—perhaps even trivially—true than the idea that freedom, in the artistic as in any other domain of action, obtains in an inverse relationship with constraint? It seems almost analytically true, in the sense that our notion of freedom is defined at least in part by the absence of constraint. You’re free to express your beliefs if there’s no censor around to penalise or imprison you if you give expression to what are deemed politically unacceptable beliefs. You’re free to travel throughout a given territory which grants you such freedom of movement (for us Brits, that now means just the UK, but it used to mean the whole of the EU), and there are no border agents around to inhibit your movements. In these cases, your freedom to express your beliefs and to travel (within the territory) are, precisely, unconstrained—that is what it means to have such freedoms.

Very importantly, these freedoms are in practice conditional on freedom from poverty, that is, on your economic well-being: you won’t be in a good position to exercise the freedom to express your beliefs or to travel the territory if you’re constrained by a lack of material means. As David Axelrod makes the point: “If you’re sitting around the kitchen table talking about democracy and the rule of law, chances are you’re not worried about the cost of the food on your table” (Smerconish 2024). And the more material means you have at your disposal, the greater your freedom to exercise these other freedoms. This economic caveat doesn’t change the logic of our orthodox understanding of freedom, according to which freedom means freedom from constraint; it simply identifies a further constraint which can limit our freedom.

It seems odd, then, not only that this apparent truism might not be quite true, but that something like the opposite might be true—at least in certain contexts. However, that is just what a good number of artists and theorists of art tell us. “[I]n art as in everything else, one can build only upon a resisting foundation: whatever constantly gives way to pressure, constantly renders movement impossible”, argues Igor Stravinsky.

[M]y freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit. (Stravinsky 1947, 64-5)

Stravinsky’s formulation courts paradox; part of our task is to figure out whether we can illuminate the source of the conundrum and restate it in less paradoxical fashion.2

Writing in a less personal, more coolly theoretical mode, Rudolf Arnheim famously declared: “Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object” (Arnheim 1983, 57). When an artist goes about creating a new work, they come up against the “conditions of reproduction”—by which Arnheim means the tools and materials constituting a given artform. Minimally, for a painter, that means a surface to be marked, an instrument with which to mark it, and a substance applied by the instrument to mark the surface; for a filmmaker, a camera, a set or a real location, and the capacity to edit the shots produced by the camera.3 Both must work with, and within the limits of, these conditions of reproduction. Arnheim famously advocated for filmmakers to limit themselves to the technological “conditions” of “silent cinema”, eschewing the temptations of colour cinematography and synchronous sound. But even filmmakers embracing these innovations in the technological basis of film still worked within a set of conditions of reproduction—precisely those set by the new technology. Though the conditions will vary across artforms and across time and place, no artist working with(in) a medium can avoid constraints of this type.

Beyond the limits set by the technology with which an artist works lies another set of constraints: that vast and motley array of routine practices we label conventions. In the context of the arts, a convention is any well-established norm of practice that is understood by both artists and appreciators (including the professional variety of the latter, known as “critics”, as well as ordinary readers, listeners, and viewers), and is understood by them mutually (that is, an aspect of an artist’s understanding of a convention is that appreciators understand it as well, and vice versa).4 In the context of film, to take one example, we can distinguish narrative and stylistic conventions. The narrative convention of closure is the practice whereby the major questions raised by a narrative film are answered, and the immediate fate of the central characters is resolved at the end of the film. The stylistic convention of shot/reverse-shot is the practice of alternating shots of two or more interacting figures, founded on the pattern of conversational turn-taking, while maintaining consistent screen direction across distinct shots (if character A is shown to the left of character B in shot X, then even as the camera changes position to shot Y, character A will still be represented as situated to the left of character B). [See Figure 1]

Note that describing a representational or artistic practice as a convention does not necessarily mean that it is arbitrary—that an indefinite range of other practices would have served the functions of the conventional practice just as well. The function of the shot/reverse-shot sequence is to represent, in a streamlined and dramatically heightened form, the states of mind—beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions—of two or more characters as they interact. Such character-focussed interactions are central to Hollywood-style storytelling; the degree of intensity of these encounters among characters will vary with the rise and fall of the action, but will typically be marked by a high degree of clarity with respect to what characters want and what is at stake in the unfolding story.

The shot/reverse-shot practice does not conjure up such dramatic focus out of nothing, however. Such conventions “[cannot] grow except on the rich substratum of universal, naturally developing event comprehension” (Boyd 2009, 151-2), and more generally on the basis of the “contingent universals” of human cognition and behaviour (Bordwell 2008; Nannicelli 2017). Conversational turn-taking is one such contingent universal: across time and place, humans interact through alternating the role of speaker and listener. (Of course the shape of such conversational interaction will vary beyond this basic structure, and the dynamics of social power will undoubtedly shape their exact form: who gets to speak, when, and for how long.) Deictic gazing—the instinct to follow the gaze of an interlocutor to its target—is another contingent universal; attending to whatever our fellow humans attend to and deem significant in the immediate environment of interaction is basic to human behaviour. Shot/reverse-shot builds on both universals: the alternation of shots mimics the pattern of alternation in conversational turn-taking, and the reciprocal glances of the characters towards each other tighten our attention on them, drawing on our hardwired, evolved and embodied understanding of the significance of such glancing.

While in the first instance filmmakers, and in the second instance critics, are more likely to possess explicit knowledge of routine practices like shot/reverse-shot and narrative closure—that is, they are more likely to be able to describe them in abstract and theoretical terms, as I have done here—what filmmakers, critics, and ordinary viewers share is familiarity with the look, feel, and function of these conventions. They know a shot/reverse-shot sequence when they see one and have a tacit understanding of its functions. Similarly, they experience the “sense of an ending” when a narrative work heads towards closure, and tacitly recognise the function and importance of such resolution in (canonical) narrative form. This tacit knowledge is comparable with linguistic competence: ordinary speakers of a language are skilled in both generating and understanding utterances, even though they do not possess a self-conscious, theoretical understanding of language in general or any particular language they speak (their ability to describe the grammatical rules of the language will be limited, for example).

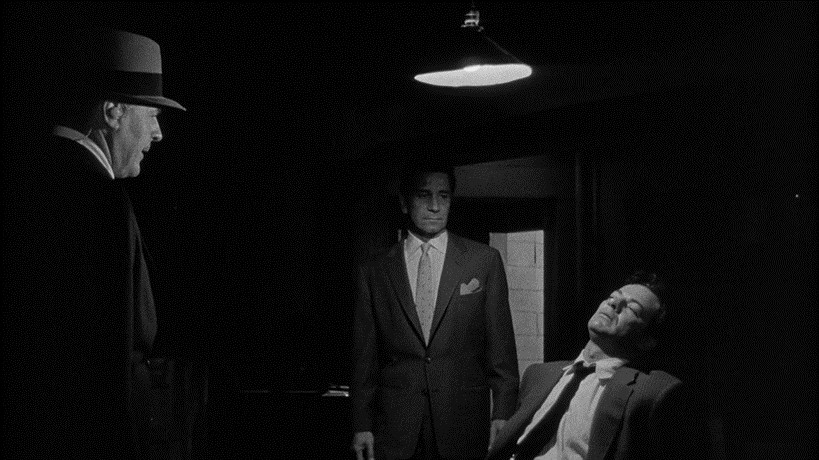

Longstanding conventions, working in clusters, form genres, or at a higher level, traditions. Thus, we can recognise a variety of genres—romantic comedy, horror, the war film, the Western, and so on—all of which work within the broader parameters of the Hollywood tradition. The clusters of conventions which constitute genres, or the broader traditions of which they form a part, are themselves (in part) matters of convention. The Hollywood crime thrillers of the 40s and 50s that came to be labelled films noirs were (as the tag implies) typically shot in black and white, and—picking up on the point above—that norm of practice wasn’t arbitrary; a low-key, monochrome palette was a good expressive fit for the bleak mood of the stories these films told. [See Figure 2]

As we can see from this example, the claim that a convention is not arbitrary does not depend on it being directly traceable to and explicable by an underpinning contingent universal (as is plausible in the case of shot/reverse-shot). In this case, what motivates and explains the routine choice of black and white for crime thrillers is that a well-established photographic and cinematographic convention (that black and white tonality conveys dark moods effectively) would fulfil the expressive function appropriate for the emerging trend in crime films that came to be called film noir. In this way conventions may build upon on one another, and a convention may be motivated (rather than arbitrary) by drawing on the affordances and associations of other conventions, and not only by implicit, direct appeal to a contingent universal.

So the use of black and white for crime thrillers was a motivated norm in this sense; but one that could be broken, as seen in Leave Her to Heaven (1945): as nasty a film noir as one could wish for, resplendently shot in—Technicolor. [See Figure 3] For critic James Agee, the combination was jarring: “the story’s central idea might be plausible enough in a dramatically lighted black and white picture”, he averred, but the “rich glare of Technicolor” was inappropriate (quoted in Berliner 2017, 106; see also Keating 2010, Part III). By the time of the neo-noir trend in the 1990s, however, colour had become the norm for such films, as seen in L.A. Confidential [see Figure 1, above]. To some extent, the choice of black and white in the original noirs, and colour in the later neo-noirs, was overdetermined by the broader cinematographic norms of the period: in the 40s most films were shot in black and white, while by the 90s, most were shot in colour.

Similarly, while the use of shot/reverse-shot is pervasive in Hollywood filmmaking, but some directors—most famously Orson Welles and William Wyler—depart from this widely-observed convention by rendering dramatic scenes in other ways and using shot/reverse-shot much more sparingly than in the typical case. Decried at the time by some, the departure from convention was also celebrated, by André Bazin and generations of subsequent critics. David Bordwell suggests that continuity editing, of which shot/reverse-shot is a central component, is so tenacious “because it has proved itself well suited to telling moderately complicated stories in ways that are comprehensible to audiences around the world” (Film Style, 155), and such cross-cultural accessibility is a goal of Hollywood as an institution. Once again, the norm is well-motivated; but for all that, as the cases of Welles and Wyler demonstrate, it is not inviolable.

As these examples tell us, not everything can be a matter of convention, in both a metaphysical and a historical sense. A convention is, or describes, a type rather than a token; it describes a norm of practice, not any particular instance of that practice. An individual token—a particular work—can be more or less conventional, and thus specific, highly-conventional works can serve as useful examples of conventions. But it would be a category mistake to construe an individual work as a convention, since the concept “convention” describes a more abstract kind of object (viz, a type).

Metaphysically, then, we need to acknowledge both tokens (individual works) and types (conventions, practices, and norms forming the context for the making and reception of individual works). This has at least two implications. Any act of tokening—of artistic production—will have a minimally creative dimension, by virtue of bringing a new, quantitatively-distinct work into being. Even a work judged to be utterly conventional will be “novel” in this minimal sense: something that did not exist before now does exist.5 Registering the distinction between tokens (works) and types (conventions) is also important historically, for it is through tokens—individual works—that invention is realised. Conventions don’t fall from the sky: practices have to be invented and explored before they can become norms, even where they exploit contingent universals like conversational turn-taking and deictic gazing, or existing conventions such as the use of black and white tonality to express pessimism.

Things change; the arts have histories, evolving internally and in response to social, political, and technological developments. These observations bring new questions into view. How do filmmakers create new experiences for us, engaging us through novelty, against the background of established convention and tradition? How are we as spectators able to grasp these innovations—given that they are precisely new? And how does all of this relate to the question of artistic freedom and constraint?

3. The problem-solution dynamic

Earlier I suggested that the absence of constraint is simply part of the definition of freedom, and so the folk axiom that the fewer the constraints faced by an artist the greater the creative freedom they enjoy is straightforwardly a matter of logic. Resistance to the axiom is therefore futile! That’s what makes it an axiom.

Where we humans are concerned, however, logic is never enough. In coming to understand the apparently paradoxical idea that artistic freedom increases with constraint, we enter the world of psychology. In particular, it is through the psychology of problem-solving that we arrive at the revised conception of artistic freedom. Problem-solving is central to human cognition, and may be defined as a “higher-order” form of cognition which recruits our basic cognitive capacities (of perception, memory, causal inference, affective appraisal, and so on) in the cause of finding solutions to both unique, and recurrent, problems faced by human agents. James Peterson puts such problem-solving at the centre of avant-garde film spectatorship:

[W]hen we encounter an avant-garde film, we struggle to integrate details into coherent wholes. We may even have trouble perceiving individual images. The process of comprehension, usually taken for granted, is suddenly laid bare. (Peterson 1994, 13)

But art appreciators more generally engage in a kind of problem-solving, when they ask themselves the fundamental questions: what kind of a work is this, and what sense do I make of it?

So we can think of viewers of paintings and films, music listeners, theatregoers and the operati—art appreciators in general—as, whatever else they are, problem-solvers. But given that the problem posed in the present essay concerns the freedom of the artist, our focus must fall on the activity of that figure, and the extent to which that activity can be construed as a kind of problem-solving. Drawing on the model of E. H. Gombrich in art history, Bordwell made such a perspective central to his understanding of the interplay between invention and convention, or what he termed “the dynamic of change and continuity”, in the history of filmmaking (Bordwell 1997, 155; for a wider exploration of the art-historical background, see Burnett 2008).

The most basic problem a filmmaker faces is: how can I make this film? or, how do I get this project out of development hell? Filmmakers, like all artists, as Paisley Livingston puts it, face the “very general problem of finding a way to make or do something the experience of which can be intrinsically worthwhile or rewarding for some audience” (forthcoming 2025, 2). But this most fundamental—and if a filmmaker is to sustain a career, recurrent—problem breaks down into a multitude of more modest problems (what location should we use for this scene?), which in turn break down into yet smaller problems (given that we’re using this location for a night-time scene, should we shoot at night, or shoot day-for-night?). At this level, as Bordwell suggests, “[f]ilmmaking is an avalanche of such minute choices” (Bordwell 1997, 149). In this way the act of making a film can be modelled as a temporally-extended, large-scale problem which breaks down into ever-smaller problems, nested within one another. The dissection of the overarching problem into sub-problems is not just an artefact of the analysis of problem-solving, but an important aspect of the problem-solving process itself—making that process tractable.

The problem-solving perspective is thus a pragmatic account of artistic creation, emphasizing craft skills and the agency of artists, standing in contrast to both the Romantic and the culturalist perspectives. While the Romantic perspective focuses on the individual as a source of creativity (and in the ideal case, of genius), culturalism puts the stress at the collective, social level. In the latter case, little attention is paid to the realisation of social norms—including artistic norms—by individual actors, making it difficult to see how such norms are either invented, sustained, adjusted, or challenged in the course of their enaction. In the former case, little attention is paid to the context in which the artist finds him or herself, the array of existing traditions and norms with which and within which they must work. The problem-solving perspective steers a course between such Romanticism and culturalism, insisting that, on the one hand, social norms of practice only come into being through the actions of individual agents, working to propose, consolidate, or change these norms, while on the other hand, the artist—no matter how exceptional the individual’s creative intelligence, and no matter how strong their impulse to break with convention and forge novel interventions—can only act within a socially-established, sustained, and sanctioned normative context.

Relatedly, the problem-solving account readily recognises the agency of both individuals (producers, directors, editors, screenwriters, and so on) and groups of various types and sizes (for example, the studios, the various film unions and guilds, the Motion Picture Association and its predecessors). We can thus reframe the goal of cross-cultural accessibility pursued by Hollywood as a problem recognised, tackled, and (more or less successfully) solved by these various agents, acting in co-ordination.

Beyond their size and scale, we can distinguish the problems faced by artists along various other axes. The problems confronted by artists have something like an “arc” of development: the problem of inception, of giving a new idea the first outline of definition, is very different to the problem of development, of giving the idea substance and structure, and to the problem of completion, of driving a now developed idea towards a finished state. Some problems will be foreseen, others unforeseen; things change. Bordwell suggests that many problems will be extrinsic to a particular project, in the sense that they will arise in relation to all projects of a certain type. A narrative filmmaker, at least one working within mainstream norms, will thus always face the following questions:

How do you ensure that viewers recognize the main characters on each appearance? How do you delineate cause and effect in unambiguous ways? How do you portray psychological states that propel the action? How do you draw the viewer’s attention to the most important events in a shot or scene? (Bordwell 1997, 151)

Filmmakers and artists also face intrinsic problems, that is, problems of their own making—problems which are unique to each particular project. Patrick Keating analyses a montage sequence in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) as a solution to a specific problem posed by the film: how do you represent the absence of the past? (Keating 2018, 01:35). Every project will give rise to such problems, but in some cases, the artist showcases a problem, setting it up as a challenge and putting it at the very centre of the work. Hitchcock liked to work in this way: how can you make a film where the action is restricted to a few square metres? Well, you make Lifeboat (1944). How can you make a feature-length film which appears to do without editing, relying wholly on staging and camera movement? You make Rope (1948). Such experiments in form have been embraced by many contemporary filmmakers: in Buried (2010), Rodrigo Cortés pushed the conceit of Lifeboat still further by restricting the action to the space of a coffin buried underground; in Memento (2000), Christopher Nolan—and before him, playwright Harold Pinter, with Betrayal (1978)—created for themselves the challenge of narrating a story backwards.

4. Constraints again: Chosen, imposed and invented

Artists and filmmakers like Hitchcock, Pinter, and Nolan, who “put formal problems at the center of their work” (Bordwell 2006, 74), allow us to see most clearly how the problems and challenges faced by artists work as productive constraints. Elster (2000) provides a taxonomy and analysis of such constraints. From the moment that Damien Chazelle envisaged La La Land (2016) as a musical, he elected to work with(in) the conventions of the musical—a quite different set of conventions from those evident in a drama about music, like Chazelle’s breakthrough film Whiplash (2016). In such cases, the constraints are, in Elster’s terminology, chosen by the artist.

By contrast, many constraints will be imposed on the artist by factors over which they exercise little or no control: physical and technological (Arnheim’s “conditions of reproduction”, for example, like the limits on the length of an individual shot at the time that Hitchcock made Rope, or the limits to the possible height of buildings given the materials and building methods available at any given historical moment); financial (limits to the budget available); legal-regulatory (consider the constraints imposed by the Production Code on Hollywood filmmaking of the studio era); and perhaps also perceptual-psychological (on the view of some music theorists, serial composition runs up against the limits of what humans are capable of discerning through listening, and so in some sense fails as an artistic project—see Raffman 2003). Unforeseen accidents will also impose hard constraints: when Heath Ledger died during the shooting of The Imaginarium of Dr Parnassus (2009), the project could not be completed as planned—a situation driving a renewed burst of creativity as Terry Gilliam and his team worked to find a way of reimagining parts of the film in order to bring it to completion; that is to say, to find a solution to the problem of Ledger’s untimely and unanticipated death.

Consider also the following two examples of creativity engendered by constraint from the world of rock music. In 1980 Peter Gabriel released his third solo album—titled Peter Gabriel, just like his first two albums. The album marked a notable shift in the overall sonic and musical texture of Gabriel’s work, arising from a number of changes in instrumentation, composition, and production style. Salient among these changes was a new approach to drumming, in which use of the hi-hat and cymbals was eschewed. Here we encounter a third type of constraint noted by Elster: those constraints invented by artists. Such constraints are chosen by artists, though not chosen from an array of existing conventions; rather they are brought into being—precisely, invented—through the specification of the constraint itself. The decision to dispense with hi-hat and cymbals went hand in hand with—perhaps causing, perhaps being caused by, probably both—the adoption of various African drumming techniques. The resulting album has a quite different rhythmic and textural character to anything produced by Gabriel as a solo artist previously, or by Genesis (the band through whom Gabriel had found fame), or pretty much anyone in the history of rock music up to that point.

Gabriel’s fourth album, once again called Peter Gabriel, continued with the percussion experiment. With his fifth album the (self-imposed, invented) cymbal embargo was lifted, Manu Katché’s hi-hat driven rhythms playing a key role on several tracks. As Elster notes:

The creation of a work of art can (…) be envisaged as a two-step process: choice of constraints followed by choice within constraints. The interplay and back-and-forth between these two choices is a central feature of artistic creation, in the sense that choices made within the constraints may induce the artist to go back and revise the constraints themselves. (Elster 2000, 176)

Thus, having explored the percussive space cleared by removing cymbals and hi-hat—the choices available within the space created by this constraint—Gabriel changes the choice of constraints.

And so also with the self-imposed prohibition on the provision of unique linguistic identifiers for his albums, this fifth solo album being named So (albeit conceived by Gabriel as a kind of anti-title, adopted as a concession to record company pressure for a unique album title—in Elster’s terms, an external, imposed constraint). Having explored the space of possibilities created by forgoing a distinctive album title—one effect of which is to push fans to identify the first four Peter Gabriel albums via their distinct visual designs, the albums becoming informally known as “Car”, “Scratch”, “Melt”, and “Security” [see Figure 4]—Gabriel relaxes this particular invented constraint from this point on in his career (his subsequent albums bearing the titles Us, Up, Scratch My Back, New Blood, and I/O). Thus, in respect of both Gabriel’s approach to album titles and percussion, with So he switches back from idiosyncratic, invented constraints to much more familiar conventional constraints.

Cut forward twenty-five years and we find Nick Cave, a musician one generation on from Gabriel, performing a similar creative manoeuvre. After almost a quarter-century of musical activity under the guise of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, along with four other members of the Bad Seeds, Cave formed Grinderman, a kind of allotrope of the Bad Seeds. While in the Bad Seeds Cave sings and plays piano and keyboards, in Grinderman he sings and plays guitar. As with Gabriel’s games with percussion, and notwithstanding the many continuities between the Bad Seeds and Grinderman, Cave’s switch from piano to guitar makes a significant difference. By adopting a new set of constraints and working within a different set of parameters—those of the guitar, which Cave played with less conventional facility and expertise than the piano, though with plenty of gusto—Cave jolted himself out of certain routines associated with and reinforced by his role as a pianist. Cave describes the strategy in relation to the band as a whole:

When I went in to do [Grinderman (2007)], I deliberately made it difficult for the band, in that I took away the instruments that they normally play, and they played other instruments. Mick Harvey didn’t play electric guitar, but played acoustic guitar; Warren [Ellis], who’s traditionally played violin, didn’t bring his violin to the studio; there was no piano, which is a huge change for the Bad Seeds, I mean there was very little piano (…) and that is my instrument (…). No matter what we did it had to sort of sound different because of that (…) the guitar is something you kind of embrace, and the piano you kinda—when you play it, you sort of push it away. It feels very different (…). And you kinda got the history of rock ’n’ rock in your hands, with a guitar. Suddenly it’s like, “oh—that’s why rock ’n’ roll is the way it is”. (Gross 2008)

The new parameters of the guitar come with different affordances, of both a negative and a positive variety: a guitar, like a piano and any given instrument, enables some things and disenables others.

Earlier I noted Arnheim’s stress on the importance of the technological constraints of a medium in spurring creativity: at the time that Arnheim first composed his treatise on the art of film, it was necessary for a filmmaker to render a world of colour and sound in the form of black and white moving images unaccompanied by recorded synchronous sounds. In artforms dependent on advanced technology, like film and recorded music, the shaping force of technology is often evident: the unique sound of Gabriel’s third and fourth albums is a case in point, as is the impact of digital technologies on contemporary filmmaking in general. Very commonly our folk axiom is applied in relation to technological developments: the more options a technology affords us, the more it enhances our creative freedom, so the story goes. But again, this is at best just half the story. In a discussion with Jarvis Cocker, Paul McCartney stressed the creative and aesthetic benefits of the very tight recording schedule The Beatles had to work within during their early years (Cocker and McCartney 2018). Cocker jests that in the time it took The Beatles to complete the recording of a song, nowadays the sound of the snare drum might be set; commenting on the discussion in same spirit, Dan Barratt (2024) has suggested that, if the band, and their producer George Martin, had had at their disposal the options and flexibility of contemporary recording technology, The Beatles might still be working on A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

McCartney’s point concerns the benefits of temporal constraints in relation to the production of art: the right amount of temporal pressure during the making of a work can be creatively and aesthetically fertile. But note that the temporal constraints imposed by the type of work being produced may be similarly beneficial. Geoffrey O’Brien remarks that the tv sitcom “[Seinfeld’s] best episodes [twenty-two minutes long, excluding adverts] feel like feature films, and indeed have busier narratives than most features (…). Comic opportunities that most shows would milk are tossed off in a line or two. The tension and density of working against the time constraint is a reminder of how fruitful such constraints can be. If Count Basie had not been limited to the duration of a 78 rpm record, would we have the astonishing compression of “‘Every Tub’ (three minutes, fourteen seconds) or ‘Jumpin’ at the Woodside’ (three minutes, eight seconds)?” (1997, 13-14; cited by Elster 2000, 211 n92). In case of 78 rpm records, the tight temporal constraint arises from the limits of recording technology at the time; in the case of Seinfeld (1989-98) the relative brevity of the episodes arises from institutional norms relating to television broadcast windows and advertising practices in the US. So while the character and origin of the durational limits of the recordings and the show differ, what they share (on O’Brien’s argument) is the positive potential of temporal brevity built into the form of the work.

Some trends in contemporary music are precisely a reaction against the omniflexible character of digital recording: “When computers made home recording mainstream at the turn of the century, musicians could experiment with the cut-and-mix aesthetic to a vastly greater degree. Before then, the cost of recording and producing professional-sounding music had been exorbitant for most people; afterwards, a diligent one-person band could produce a lot of music for almost no expense. This helps explain why dub became a subcultural phenomenon in fin-de-siècle Germany. When almost anything seems feasible, self-imposed limits have a powerful allure” (Bertsch 2024). In Elster’s terms, dub musicians invent their own constraints, carving out a much more delimited space of sonic possibility than the underlying technology allows.

5. Four ways to solve an artistic problem

Elaborating a schema devised by Noël Carroll—in turn suggested by the work of Arthur Danto—Bordwell suggests that there are broadly four ways in which artists can solve the problems they face, constituting a spectrum of options: through the replication, amplification and revision, synthesis, or rejection of the artistic norms that they inherit.6 An artist can play it safe by working to observe the norms of an existing framework; a love song, a horror movie, a heist film. Or they can take those norms and intensify or extend them, without fundamentally changing the underlying form or challenging an appreciator’s ability to latch onto that form; in modest scope, such revision is probably the most common type of artistic production. Moving further along the spectrum, artists may synthesize existing forms, as with genre hybrids: consider the blending of gangster and domestic drama in The Sopranos (1999-2007) or the fusion of new wave and dance elements in the music of Talking Heads. At the opposite pole of the spectrum we reach the outright rejection of a set of norms, a strategy requiring either that the artist appeals to some other set of norms, or in the very act of rejection, instantiates a new possibility; while revision involves a difference in degree, rejection involves a difference in kind. And if the new forms generated through either synthesis or rejection persist, they themselves become targets for replication, revision, synthesis, or rejection, and so the process iterates.

Bordwell’s schema can be understood, then, as a way of concretizing the dialectic between convention and invention. Artists always create against a background of norms and established conventions, but always have the scope for invention. As Brian Boyd notes, “we need to imitate in order to innovate” (2009, 122). Note, however, that although there is clearly a sense in which, as we move from replication towards rejection, the artist exercises their capacity for invention to a greater and greater degree, works in all parts of the spectrum can be realised with more or less skill and care. That is why it is possible to find and praise excellence in an artwork which works from and stays within—in Bordwell’s terms, one which replicates—an established set of norms. Many well-crafted genre works fit into this category: a thriller or horror film might engineer its thrills and frights exceedingly well while working entirely within the relevant genre conventions.

For this reason, as James Ackerman notes, it is important to distinguish between novelty (in my terms, inventiveness) and quality (the realisation of value) (Ackerman 1991, 17). Something can be novel without being of any great value: Kant held that nonsense expressions exemplify this possibility (Kant 1952, §46, 168). Boyd concurs: “Most novelty matters little. Every move we make is in some sense new, yet unlikely to be of lasting moment” (2009, 120). And as we’ve just seen, something can be excellent in a given domain without being significantly novel or inventive: the beautifully wrought Adirondak chair that graces the porch of my rented summer house is a fine example of a now-generic design dating back to the early 1900s, conforming entirely to our expectations of its form. With this point in mind, many theorists of creativity define the latter as the combination of novelty with quality; they argue, that is, that we should only bestow the honorific “creative” on an action or object which embodies both originality and value (“quality”, in Ackerman’s terms). Berys Gaut argues that the originality of a creative act or product is quite distinct from its value, on the basis of the Kantian insight noted above: that there can be original (and in that sense “creative”) nonsense—and nonsense, by definition, can’t be valuable. “So we think of Picasso and Braque as exhibiting creativity”, Gaut concludes, “partly because of the originality of their Cubist paintings, but mainly because that originality was exhibited in paintings which, considered apart from their originality, have considerable artistic merit” (2003, 150, my emphasis).

But this analysis may not be strict enough, to the extent that we think of the novelty and the value of a creative item as bound up with one another. If the original properties of a creative entity are allowed to float free of its valuable properties, then the Kantian worry looms again: a spoonful of original nonsense allows us to regard an act or object as creative, but because these properties are separate from those that make it valuable, our sense that it is authentically creative is diminished. Putting the point in positive terms, we may say that i) a work exhibits creativity through its realization of original, (artistically) valuable properties, and ii) that the more the originality and the value we attribute to a creative work inhere in the same properties of that work, the more we will be inclined to judge it creatively excellent. The most obvious case where this holds is when we claim of an artwork that it is insightful (or any cognate claim that an artwork is epistemically valuable), for the claim entails that the work is not only cognitively substantial, but in some way novel (otherwise it could not be said to offer an insight).7

For a further example, we can return to Peter Gabriel’s early solo career. We might say that the artistic excellence of Gabriel’s third and fourth albums lies (among other things) in their atmospheric, cymbal-less and tom-tom heavy percussive soundscape—in those very features of the work that are most original and arise from the creative agency of Gabriel and his collaborators. We would then want to say that the reason we attribute such a high level of creativity to these recordings, or to the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque, is that their originality, so to speak, saturates them; we cannot easily disentangle their great originality from whatever other artistic virtues they may possess. So the mark of creativity is the convergence and integration, and not merely the co-presence, of originality and other forms of value (Smith 2024b).

6. Conclusion: The sweet zone of creativity

With the various examples sketched above in mind, let’s return to the underlying idea: that far from diminishing the artist’s freedom, constraints function to increase and realise that freedom. But exactly how and in what sense do constraints work to increase the freedom of the artist? Elster and Bordwell contend that the constraints function to focus the attention and creativity of the artist. By providing focus, the artist is liberated from the oppression of the blank page and the empty canvas, enabled to move more readily from nothing to something, addressing the problem of inception in particular. Perhaps it isn’t, after all, exactly freedom that the constraints create, so much as encouraging and facilitating action by limiting choice. As Livingston puts it, precommitment to a set of constraints “forestalls aesthetic indifference [and] directionless scrutiny” (Livingston 2009a, 140). The constraints help to free us from creative inertia, from the indecision of Buridan’s ass, paralysed by too many equally tempting options. But the constraints must not be “too tight”, lest the artist be left with too little room for creative manoeuvre. Elster (2000, 210, 234-40) suggests that Stendhal backed himself into a creative corner, in just this way, with his unfinished novel Lucien Leuwen—unfinished, on Elster’s account, because Stendhal had no viable narrative moves (given his rigid views concerning romantic conduct) available to him.

Constraints help the artist to focus, and in that way address the problem of inception. But they also assist with the problems of development and completion. Once the artist settles on a set of constraints, the psychological reward of realising a successful work within these constraints beckons. “[T]he overcoming of obstacles is in itself a liberating activity”, writes Marx (quoted by Elster 2000, 178). It’s instructive to return to Stravinsky (1947) at this point in the proceedings: “My freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles”. Like Marx, Stravinsky recognises the importance of obstacles to push against and overcome in realising his freedom—his scope for artistic agency—and making it meaningful. All the theoretical artistic freedom in the world will be meaningless—without value—unless it can be cashed in for purposeful action in relation to the realisation of an artistic project. The constraints provide the framework for such meaningful, focussed action, placing the artist in the space of creativity, neither stifled by too slender a set of options, nor incapacitated by a surfeit of them.

If this is correct, it is not the case that artistic freedom continuously increases with increasing constraint, as Stravinsky claims, but rather there is something like a sweet spot—or a sweet zone—of creativity poised between the poles of procrastination (wrought by too many options) and suffocation (produced by too few). The relationship between creativity and constraint is thus not linear, but rather takes the form of a bell curve. This is the grain of truth in the folk axiom: our artistic freedom does increase with fewer constraints, up to a point—that point being the sweet spot, or zone, of artistic agency; in other words, the space of creativity. To return to the example of The Beatles: while McCartney notes that too many options can hamper creativity, it is important to remember the creative ferment engendered by advances in recording technology in their later albums, particularly from Revolver (1966) onwards. The new technical options and greater flexibility—the diminished constraints—were creatively enabling.

Stravinsky’s claim is, then, a corrective overstatement, in the sense that the inverse of the axiom is not true: it is not the case that artistic creativity simply increases with more constraints. Stravinsky’s overcorrection functions as an instance of a “felicitous falsehood”—a claim which is literally false, but takes us closer to the truth. In Catherine Elgin’s words, such a claim is “an inaccurate representation whose inaccuracy does not undermine its epistemic function” (2017, 3).

Although this analysis of the nature of creative freedom has particular purchase in relation to the arts, its relevance extends well beyond this context.8 Consider the case of sports and games. Games by definition are structured by invented rules, which create a space within which players seek excellence (of strategy, physical or cognitive pre-eminence, and so on—paradigmatically, by winning). The constraints provided by a set of rules and the “game space of possibility” are necessary for players to realise creativity and excellence. These rules can be and often are tweaked in order to optimize the dynamics of games, and increase the affordances for excellence—to strike the right balance between constraint and freedom, necessity and flexibility. As Elster notes: “there is a ceaseless adjustment of rules so as to make athletes and players bound neither too tightly nor too loosely” (2000, 281). Or as Ken Bruce, co-creator of the BBC radio quiz game PopMaster, puts it:

[N]obody wants to listen to a quiz, where people are [always] getting the wrong answer and scoring zero points. You want people to score well, but you don’t want them to know everything. (O’Connell, 2024)

Our item of folk wisdom is, then, a half-truth: artists need a space of possibility within which they can exercise their agency. If that space is too narrowly circumscribed or entirely closed down, the artist will be paralysed; that hazard is recognised by our folk understanding of artistic freedom and creativity. What I hope to have made salient here is the other side of the story, which that same folk theory obscures (as Stravinsky saw so clearly): working within constraints—chosen and imposed, conventional and invented—provides an essential complementary ingredient in creative agency, facilitating and making meaningful the artist’s “theoretic freedom” (Stravinsky 1947, 64).

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Dan Barratt (in particular for suggesting the connection between the “sweet zone” of creativity and bell curve distribution, and for pointing me to the dialogue between Cocker and McCartney), and Ted Nannicelli (especially for directing me to the Terry Gross interview with Nick Cave). My gratitude also to the two anonymous journal reviewers for helpful feedback, and to Iris Vidmar Jovanović for her keen insights and endless patience.