1. Introduction

“Cringe comedy” is a subgenre of comedy that uses the audience’s second-hand embarrassment to provoke laughter in the viewer (Hye-Knudsen 2018; Mayer, Paulus, and Krach 2021). This method can make some viewers so uncomfortable, it produces the side-effect of “cringe overhang”: a term I have coined to describe instances where the cringe continues for the viewer even after the comedy has stopped. It is possible to use J. L. Austin’s speech act theory to explain that jokes are subtextual invitations to laugh. This is why cringe comedy jokes that produce only second-hand embarrassment can be said to have failed: the subtextual invitation has been refused and laughter has not been provoked. Having used Austin’s work to explain why a joke has failed, I then use Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren’s benign violation theory to explain how the jokes have fallen short. They fail to balance the strong violation of second-hand embarrassment with sufficient “benign”, a noun used to denote the editing a joke can undergo to make its violations simultaneously interpretable as safe, playful, or nonserious. This lack of benign leads to a negative emotional response in place of laughter. If audiences feel some second-hand embarrassment for the characters, they laugh. If audiences feel a strong second-hand embarrassment, they have a negative emotional response—say, struggling to watch, or wanting to leave the room. When combined, the two theories explain how cringe comedy works, and one of the pitfalls of failure: inducing cringe overhang in some audience members.

The UK sitcom Peep Show (Armstrong and Bain 2003-2015) is a perfect cringe comedy case study: shot from the point of view of its two main characters, it also presents their inner monologues, allowing for their embarrassment to be felt and “thought” by the viewer. This will be the main cringe comedy I draw examples from, though my findings apply to cringe comedy in all performance capacities, i.e. where the cringe humour is created deliberately for an audience, as opposed to situations in everyday life that happen to be both embarrassing for one person and humorous for those who observe it. People sometimes laugh through second-hand embarrassment in response to real-life events, i.e. non-performative and unintentional ones. The difference in intent between comic performer and embarrassed individual, where the former’s acts are purposeful and the latter’s are accidental, may mean a different theoretical explanation is needed. Accordingly, I have focussed on intentionally performed cringe comedy, rather than accidentally enacted cringe humour.

In order to explain the phenomenon of cringe overhang, I explain why cringe jokes can be understood to have failed, how that failure happens, and why that failure leads to cringe overhang. Firstly, I argue cringe comedy jokes are illocutionary acts designed to provoke laughter through second-hand embarrassment—explaining why cringe jokes that don’t produce laughter have failed (Austin 1975). Secondly, I draw on the benign violation theory to explain how cringe jokes can fail: by maximising the violation and minimising the benign, leading to an excess of embarrassment (McGraw and Warren 2010). Thirdly, I acknowledge that these jokes don’t always produce the desired perlocutionary effect of laughter: sometimes the joke is unable to cut through the embarrassment, and results in cringe overhang, leaving the viewer in a state of lasting discomfort. Finally, I argue that cringe comedy’s funniness is reliant on its lack of social psychological distancing. By maximising second-hand embarrassment, the comedy is less benign (i.e. a stronger violation) and more polarising as a result. This explains why cringe comedy produces a cringe overhang in some viewers, where they continue to cringe even after the comedy has stopped—and why this phenomenon is an unsurprising, and for some audiences unavoidable, part of this comedic subgenre.

2. Cringe comedy as illocutionary acts and subtextual actions

In his seminal work on the philosophy of language, How to do Things with Words, J. L. Austin coined the term “illocutionary force”. This is where the speaker makes an utterance that demands something of the listener through subtext. Take the phrase, “The oven’s off.” That could of course mean that the oven hasn’t been switched on—but this sentence implicates that the speaker’s intention is to get the listener to turn the oven on. The illocutionary force of an utterance provides a subtextual invitation for a listener to act on, which goes beyond the literal spoken words (Austin 1975, 99-100). This is a helpful way to think of jokes in comedy. Building on Austin’s work by applying it to comedy, I define “joke” as an illocutionary act inviting the audience to laugh.

Comedic actions are similar to jokes. They use subtext to invite the viewer to laugh. They do not tickle the audience and force them to laugh, nor do they actively ask or command the audience to laugh. They present the audience with characters performing actions which, like jokes, use subtext to provoke the desired laughter response. In the first episode of season one of the UK sitcom Peep Show, the character Mark Corrigan is observed by his office crush chasing children and threatening them with a metal pipe (Armstrong and Bain 2003). This happens because he finally snaps after the gang of youths have repeatedly harassed him over a period of several days. The viewer is not meant to sit and indifferently take the child chasing scene in; nor is the scene supposed to produce emotional distress or tears or a desire to hide (like a similar scene in a horror film might). Instead, Mark’s action of chasing the children—and unknowingly embarrassing himself in front of Sophie, the woman he is infatuated with—is designed to invite the viewer to respond by laughing.

So far, we know comedy is based around a desire to provoke laughter; either with illocutionary force from performed jokes, or through a subtextual invitation from performed actions. Note that I specify comedy must be performed. This helps differentiate physical comedy, like slapstick, from situations in everyday life where a person undertakes an embarrassing action that unintentionally provokes laughter. In comedy, if you chase a child with a metal pipe, that can be funny. In real life, if you chase a child with a pipe, it takes on an entirely different tone. The former is done with the intention of provoking laughter in an audience, while the latter generally isn’t. Of course, onlookers may still find real-life pipe wielding child-chasing funny. It is important to note again that the focus here is on performed cringe comedy. The clear difference in intent between comic performer and embarrassed individual could mean there are also differences between audience members and real-life onlookers, e.g. a lack of empathy in the latter. My investigations have focussed on performed comedy, so I make no arguments about everyday events.

Cringe comedy is made up of joke illocutionary acts, and performed subtextual comedic actions, which are designed to provoke laughter through second-hand embarrassment. The subgenre tends to depict characters suffering through embarrassment in the moment, rather than recounting the emotionally distressing scene after the fact. It seems that an important feature of cringe comedy is getting the audience as close to the embarrassment as possible. This is easier when the audience sees the embarrassing joke delivered, or action undertaken, in real time. An episode of Peep Show where Mark had instead chased the children with a pipe offscreen and then had the story recounted to him afterwards by Sophie may still have been funny. However, the embarrassment and the laughter it provokes by actually watching the action play out heightens the effect produced. Embarrassment, like other emotions, is heightened through direct experience. The goal is to make the audience empathise or feel the character’s embarrassment so deeply that it afflicts them like they are directly experiencing it themselves. This discomfort can provoke laughter.

In this section, I have defined cringe comedy as a comedic subgenre where second-hand embarrassment is used to provoke laughter in the viewer. In the next section, I will outline the benign violation theory and show how it can be used to explain how jokes work. This is important for defining and explaining cringe overhang because benign violation theory will later be used to show how cringe comedy jokes can fall short of their laughter-provoking purposes.

3. Benign violation theory

Expanding on prior work by Tom Veatch (1998), Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren argue in Benign Violations: Making Immoral Behaviour Funny that all instances of humour are brought about through the “benign violations” that occur when an utterance or an action is perceived as violating our expectations in a benign way (2010, 1142). A “violation” is anything that threatens our idea of how the world “ought to be”, by being unsettling or disquieting. This can be through breaking taboos or moral norms, but extends much more broadly to our expectations of daily life in all areas like language, how we move, table manners, etc. “Benign” means “safe, playful, [or] nonserious” (2010, 1142). They emphasise that violation and benign interpretations must be perceived simultaneously in order to be considered humorous.

Examples drawn from various types of joke will help illustrate the benign violation theory in action. Firstly, I’ll use a pun: “I like religious humour, but catholic jokes make me cross.” This joke violates our expectations of language use, because “cross” can mean both i) angry, and ii) a religious gesture. It is sufficiently benign because many of us lack ties to the catholic faith. Those who do have ties recognise that the punchline makes light of a quirk of language, rather than the religion itself.

In a slapstick comedy film, a clown might fall down a well—then after some seconds, suddenly pop back up again, surprisingly unharmed. Here, the fall violates our expectations of how the world ought to be in two ways. Firstly, we don’t expect people to fall down wells, especially unintentionally and out of the blue. This violates our expectations of the clown’s awareness of their surroundings (as well as our expectations of well-placement, assuming it’s somewhere unusual, like the middle of a busy street). Secondly, we don’t expect such a dangerous feat to be pulled off without injury—violating our expectations of physics. It is made sufficiently benign when it is revealed no real harm has been done, in spite of our very reasonable assumptions otherwise.

In short, the benign violation theory is a balancing act. It requires a violation of our expectations to be made playful. This is easy in the joke and slapstick comedy above, because the violations aren’t that intense. When the violation comes across a lot stronger, say, invoking a recent tragedy or morally questionable stance, increasing the benign takes more work. “Temporal, social, spatial, likelihood, [and] hypotheticality” are means of psychological distancing comedians can draw on to render a violation simultaneously benign (McGraw and Warren 2010, 1146). These methods are meant to create a feeling of space between the violation and the audience—allowing room for the violation to be interpreted as safe, playful, or nonserious. I will briefly explain how each of these methods work, along with examples of jokes that make use of them.

i) Temporal psychological distancing is where the joke-teller uses the passage of time to create a playful or nonserious buffer around the violation. In other words, it’s easier to make a joke about a tragedy sufficiently benign when said tragedy took place in the distant past. An example follows: “My house flooded the other day. It was like Hurricane Katrina, but worse—because I knew the people affected.” Hurricane Katrina was a tragedy that claimed hundreds of lives nearly 20 years ago. The passage of time has weakened audience responses to the violation, allowing it to become fodder for jokes.

ii) Social psychological distancing is where the joke-teller makes jokes about people the audience do not know, or do not have strong ties to. Audiences are less likely to feel the violation as strongly when they don’t personally know the joke targets. For example: “Fame affects people differently. George Clooney has aged like a fine wine; Johnny Depp has aged like my grandma.” Many people know of American actor Johnny Depp, but few know him personally. This social distancing allows us to enjoy jokes at his expense without feeling the violation too strongly.

iii) Spatial distancing relies on the topic of violation being far away from the audience. Because the violation isn’t in close vicinity, it is less likely to have personally affected any given audience member—thereby increasing its chance of being sufficiently benign. One example is, “I was doing a gig at a university and everyone thought I was American. You’ll never guess how many people I shot.” This uses the many school and university shootings in the USA over the last several years as joke fodder. The joke worked at my New Zealand gigs because the United States is so far away, audiences didn’t feel the mass shooting violation as strongly.

iv) Likelihood psychological distancing is where the joke-teller hopes the violation within the joke comes across as somewhat unlikely. If the audience doubts the veracity of the joke’s contents, it will be easier to laugh at its unpalatable imagery. For example, “My friend’s dad was hit by a car. She was distraught. He was crushed.” Here, the flippant treatment of the topic at hand, as well as the silly pun the punchline relies on, makes it seem unlikely the car accident (the violation) actually happened. Because we doubt anyone was hit, the audience feels the violation has been made sufficiently benign.

v) Hypotheticality psychological distancing entertains a given violation, without delivering it like an apparently truthful anecdote. Because it’s just an “imagine if” scenario, audiences can interpret it as benign. For example: “Teenagers wanting to be rebellious always get piercings without their parents’ permission. Imagine piercing your parents without their permission! That’s rebellious.” This joke doesn’t suggest non-consensual parental piercing has happened; it just asks audiences to contemplate the idea. This keeps it sufficiently playful/benign.

Simple and precise, the benign violation theory seems to best encapsulate the various occasions of humour—ranging from tickling and slapstick comedy, to puns, blue humour, and workplace humour. In short, it explains enough instances of humour to make offering tweaks and improvements to perfect it a worthwhile exercise.

There are some minor issues with the benign violation theory. Some of McGraw and Warren’s suggestions for achieving psychological distance work better than others. They later amended their arguments about temporal distancing, attempting to add some precision to the time limit within which a joke can be predicted to work (McGraw, Williams, and Warren 2014, 566). It can be argued that their “improvements” fall short by using psychological analysis of audience responses to explain when jokes should be performed. Instead, they could use the theory more practically to explain how jokes can be adjusted so they can be performed at any time.

Some thinkers take issue with the theory due to the power inequality that can exist between the joke-teller and the listener (Kant and Norman 2019). Social psychological distancing is also readily open to misuse, making jokes less effective, rather than funnier. When a joke target is in the same space as the audience, their reaction is observable. When a comedian regales an audience with stories of joke exchanges targeting people who aren’t there, hoping social psychological distancing will make the joke sufficiently benign, likelihood and hypotheticality distancing risk also unintentionally undermining the joke. When the joke target is somewhere else, the audience has reason to doubt whether the exchange took place (likelihood) and if this is just a scenario made up by the comedian (hypotheticality). Sometimes comedians must joke about people in the same room—and there’s a good chance of producing jokes that are less funny if social psychological distancing is rigorously adhered to.

In defence of the benign violation theory, Kant and Norman’s concerns of power differentials between joke-teller and listener are more relevant to a social or workplace setting, say, where the joke teller is the boss and the listener a member of their staff. Similarly, the issue I have with social psychological distancing is most likely to be an issue specifically when applied to stand-up comedy.

Despite these criticisms, the benign violation theory can be used to explain cringe comedy, how it works, and why attempts at cringe comedy sometimes fail. In the next section, I illustrate how the benign violation theory is able to do this, by creating a benign-violation graph on which cringe comedy jokes can be placed and moved as they are made more or less benign.

3.1 Benign violation theory in action

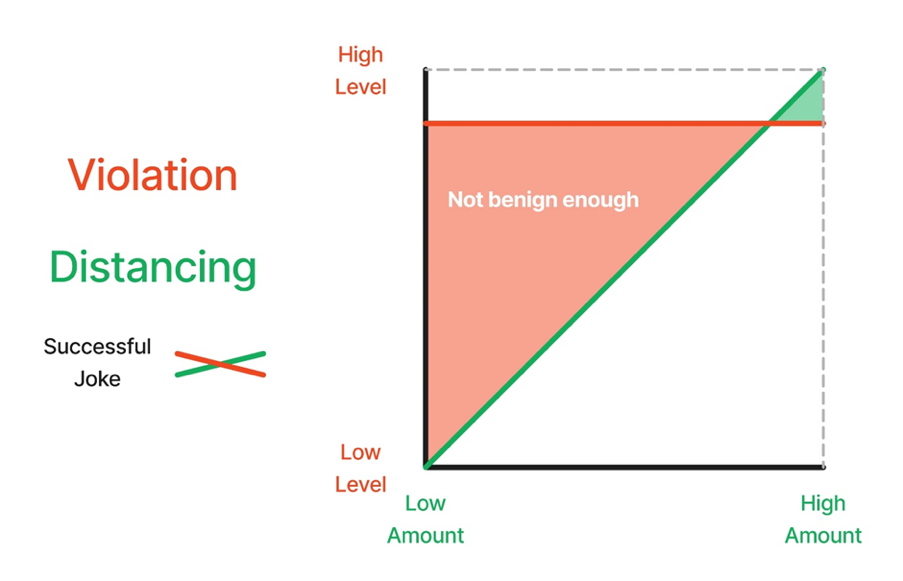

As stated earlier, for a joke to provoke laughter, it must violate our expectations of how things ought to be, while simultaneously being open to interpretation as safe and playful. This usefully restricts comedic writing by providing parameters within which we can place any given joke—including those used in cringe comedy. The theory can be illustrated with a graph showing level of violation on the vertical axis, and the increasing amount of psychological distancing on the horizontal axis. An effective cringe comedy joke will find the point where these lines intersect, ensuring the joke is benign-violation balanced.

A successful joke can neither be solely benign, nor solely a violation. If an utterance landed on either of these extremes, it would lack the simultaneous bite or playfulness, respectively, to form the unique wordplay agreeable to laughter. A comment like, “Gosh, it’s chilly today”, is solely benign. Yelling sexist remarks in the street is solely a violation (Sparrow 2024, 32). Neither provokes laughs. To be clear, a failed joke that ends up accidentally falling at either extreme, does not automatically become a statement or opinion in light of the fact it failed to produce laughter. While that should be taken into account, it also doesn’t mean any offensive remark that fails to produce laughter can be defended as a failed joke: the structure, timing, and location of an utterance usually provides sufficient clues as to whether someone is a poor joke-teller, or trying to avoid responsibility for their offensive speech.

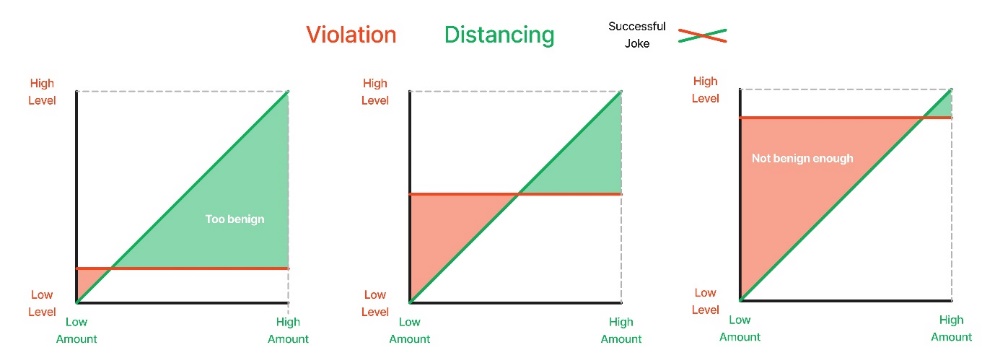

Different joke balances are illustrated in Figure 1 below.

The intersection of violation and benign is where a joke balances. As the graphs show, generally speaking, the stronger the violation, the more psychological distancing is required to effectively balance it. While jokes are subjective, and the strength of a given violation varies from person to person, the graph can still help comedians and thinkers visualise what changes need to be made if a joke isn’t working. The vertical axis shows the strength of the violation. Weaker violations, like jokes about work or the weather, will sit low. Stronger violations, like mentions of a current war or sexual assault, will sit higher. The horizontal axis shows the amount of psychological distancing used. If very little effort has been made in creating psychological distance, the joke will be towards the left. If much effort has been made to create psychological distancing—say, social, temporal, and likelihood distancing have all been used—then the joke will move to the right.

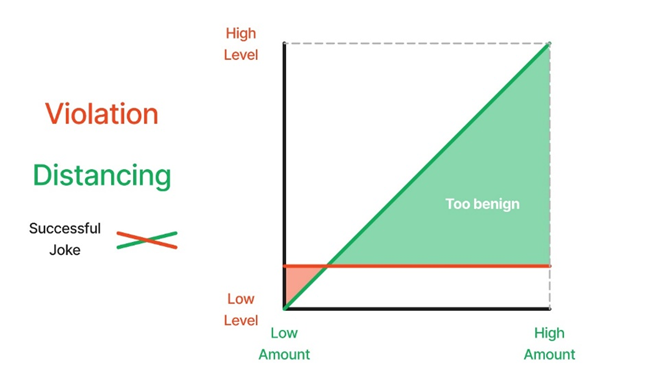

Jokes fit under various comedic subgenres, all of which balance the extremes of benign and violation differently. Comedic subgenres (from now on referred to as subgenres) will, generally speaking, align more closely with either benign or violation. For example, puns can often be illustrated with Figure 2.

Puns violate our expectations of language use, and the way we understand words. Although puns can be used in violation-heavy subgenres like blue humour and gallows humour, we tend to think of them as comparatively light or silly (Sparrow 2024, 33). Because of this, puns will often be placed low on the violation axis, and require less psychological distancing to make them sufficiently benign.

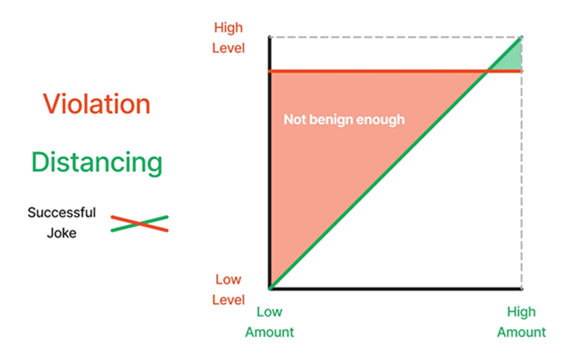

In contrast to this, stronger violations, as shown in Figure 3, tend to be present in jokes about more challenging or controversial topics like war and sexual violence.

Jokes in the subgenres of dark, gallows, blue, and political humour are typically thought of as stronger violations—meaning they are higher on the vertical axis, and require more psychological distancing to make them sufficiently benign.

The benign violation graph provides a basic framework for how jokes can be fixed when they fail to provoke laughter. Jokes can fail for a wide variety of reasons, such as unclear premises/set-ups, using too many words, and having predictable punchlines. If structural tweaks aren’t providing any answers, audience response to jokes can provide useful clues as to whether the joke is appropriately balanced. If they angrily leave mid-show, or heckle, the violation could be overpowering the joke. By identifying that a joke is too violation heavy, a comedian can work to increase the amount of psychological distancing, thereby balancing the joke. If audience members are constantly checking their watches, or are on their phones, the joke might be too benign, lacking the violation necessary to cause surprise and laughter. To remedy this, the comedian can reduce the psychological distancing to allow for the violation to be more obvious (Sparrow 2024, 34).

Having shown the benign violation theory in action, I will now demonstrate how cringe comedy relies on strong violations to produce effective jokes.

3.2 Benign violation theory’s use of violation

Strong violations occur in cringe comedy, many of which, if delivered with anything other than deft control, can come across too strongly for audiences. Comedians—a term I’m using for directors, writers, actors, and stand-up comics—can work to increase the playful, nonseriousness of the benign in a given joke in order to make the violation more palatable. This is more effective than watering the violation down or removing it entirely. A clear example of this is the sixth and closing episode of the third season of Peep Show, where Mark realises while on a weekend with Sophie that he is not in love with her, and they are not remotely compatible (Armstrong and Bain December 16, 2005). He realises this while lost in a field on a weekend away where he had intended to propose to her. When he finally manages to get back to the hotel, however, Sophie has found the ring and accepts the “proposal”, even though one was never offered. Mark “accepts the acceptance” out of sheer embarrassment and discomfort at the prospect of telling her he actually wants to end the relationship. The violation here is a man struggling to express his emotions and being trapped by them as a result. Rather than watering down the violation of a loveless marriage, the writers of the show leaned into it by showing how such marriages can begin—out of embarrassment, or a misplaced sense of duty, or from a perceived lack of alternatives. As a season closer, the prospect of an entirely avoidable miserable life ahead is poignant, as well as hilariously embarrassing.

While benign violation theory is not an attempt to explain away all violation-heavy joke-attempts as important and worthwhile social criticism, it can allow comedians a framework for sensitively approaching polarising, controversial, or otherwise difficult topics in an appropriately comedic way. Comedians need violations like the one above if they are to produce jokes capable of criticising or making light of the status quo, questioning the rationality of our commonly held beliefs, and thinking of novel solutions to difficult problems. Without the bite of a violation flipping our world upside down for a moment, a joke collapses.

In this section, I defined the benign violation theory, explained its parameters with a graph upon which jokes can be placed and moved according to how benign- or violation-heavy they are, and outlined the essential part violations play in jokes. In the next section I show how cringe comedy in particular can fail to be sufficiently benign-violation balanced.

4. Cringe comedy’s failed perlocutionary result

As previously mentioned, illocutionary acts are utterances spoken to get the listener to perform an act. If I want you to open your present, I might say, “You haven’t opened your present”. The illocutionary force of the utterance is intended to get you to open said present. The perlocutionary response is what the listener does in response to the illocutionary act. If you open the present after I tell you that you haven’t opened it, that is the perlocutionary result. If you say, “You can open it if you want”, that is the perlocutionary result. Note that in the second example, the perlocutionary result does not match the illocutionary force, i.e. my utterance has failed to garner the desired result.

Failure to achieve the desired perlocutionary effect (provoking laughter) is not a phenomenon exclusive to cringe comedy. At an open mic night, comedians will try out jokes for the first (or second, or third) time. Sometimes the audience finds the jokes funny and laughs. That’s great. Illocutionary force: aiming to provoke laughter. Perlocutionary result: laughter. They match. The jokes are a success. This is the same in comedy films and sitcoms. Illocutionary force: produce laughter through comedic dialogue. Perlocutionary result: laughter. Again, a comedic success. On the occasions where audiences don’t laugh, the illocutionary force, or subtextual invitation inviting laughter, has failed to achieve the desired perlocutionary result. Instead, it has produced frowns, heckling, silence, or some other unintended response. It is worth noting again here that while a comedic action can’t have an illocutionary force—which is a quality limited to utterances—comedic action has subtext, which can similarly fail in its invitation to laughter.

If cringe comedy jokes or actions are too embarrassing, they produce cringe overhang. Second-hand embarrassment can be so strong a violation of norms for certain audience members that it ceases to be laughable. One scene of Peep Show some people find difficult to watch is in season three, episode four, where Mark mistakes his infatuation for Big Suze—his roommate Jeremy’s ex-girlfriend—for love (Armstrong and Bain December 2, 2005). When Jeremy discovers Mark and Big Suze hugging in Mark’s room, Jeremy accuses Mark of being in love with Big Suze, then storms off. When she asks Mark if he really does love her, in an effort to avoid embarrassment, he goes way overboard in his protestations, saying, among other things, “God no… Honestly, Suze, I like you, sort of, but not even really that much. You’re very, y’know, you’re the horsey type… Big stupid posh-head, that’s you”, which scares her off. Here, the embarrassment for some viewers is so strong that it chokes off the possible interpretation of the embarrassment as simultaneously benign (and therefore funny). In these cases, cringe comedy doesn’t produce the desired perlocutionary effect of laughter—the joke is unable to cut through the embarrassment, consequently leaving the viewer in a state of discomfort. This causes the actual perlocutionary response (looking away, leaving the room, blushing) to fail to match the desired perlocutionary result of laughter. In short, the joke seems to some audience members to act only as a violation.

In this section, I explained that cringe comedy can fall short of its illocutionary aim of provoking laughter by being too embarrassing. Strong violations can appear insufficiently benign—rendering them too embarrassing, causing cringe overhang. In other subgenres, this shortcoming can normally be fixed by working to increase the benign of the joke in question. However, cringe comedy, due to its genre constraints, is not always able to do this. I explain why this is the case in the following section.

5. Cringe comedy’s reliance on its lack of social psychological distancing

You can break down cringe comedy like this:

1. Cringe comedy jokes carry an illocutionary force that aims to elicit laughter through feelings of second-hand embarrassment. Similarly, cringe comedy actions carry a subtextual invitation to laugh at second-hand embarrassment.

2. Cringe comedy can fail to achieve its illocutionary aim of laughter through this second-hand embarrassment. Instead of producing both laughter and second-hand embarrassment, the perlocutionary effect is solely the latter.

3. The benign violation theory suggests the excess embarrassment and dearth of laughter is caused by maximising the violation and failing to balance it with sufficient benign.

4. The violation of cringe comedy is deliberately caused by its lack of social psychological distancing. The audience members are made as embarrassed for the character as possible, maximising the violation. Therefore, cringe comedy is less benign and more polarising than other subgenres. (Sparrow 2024, 35-36)

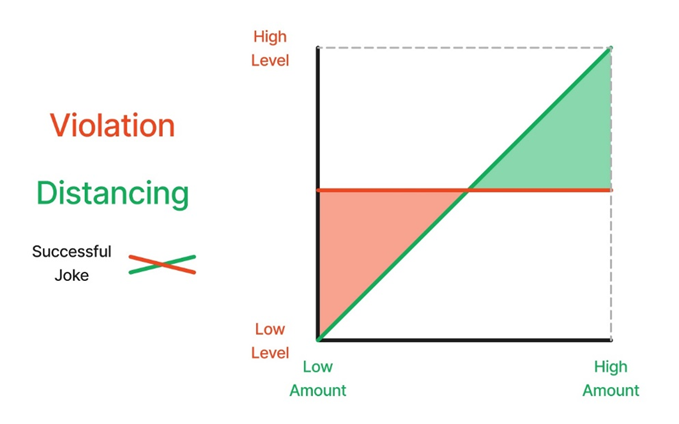

This explains how cringe comedy is capable of provoking laughter in some viewers, and cringe overhang in others. When the viewers feel some second-hand embarrassment on the character’s behalf, they are still able to laugh through it. To these viewers, cringe comedy jokes clearly feature a violation—but they’re still funny. This is because while the violation might feel more intense than, say, a childish pun, the violation is still able to be simultaneously interpreted as sufficiently benign. This is illustrated with Figure 4.

Typically, audiences experience cringe comedy as a relatively intense violation. The benign and the violation lines still intersect, so the joke remains a success. This situation is illustrated in Figure 5:

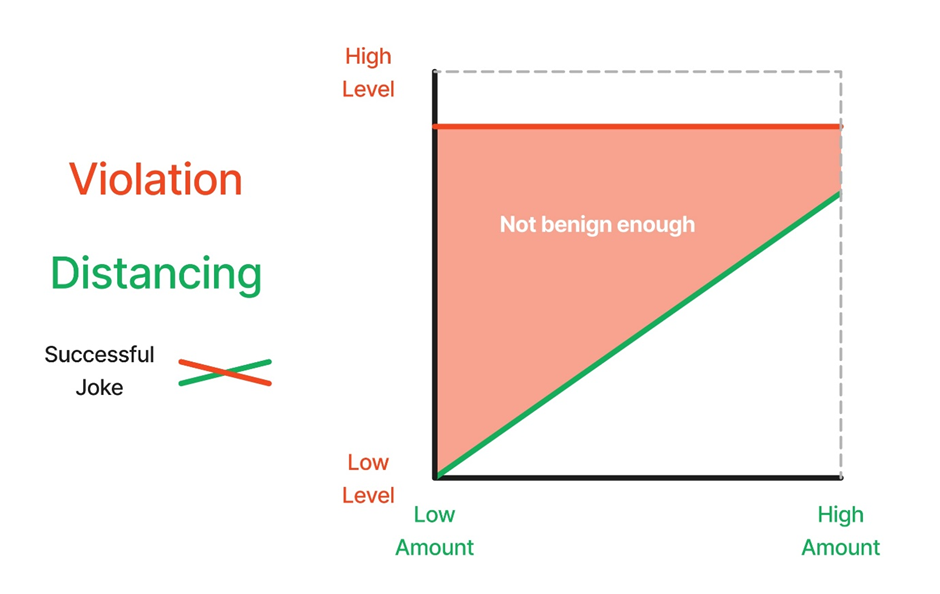

On some occasions, an audience member may experience the second-hand embarrassment so intensely that the violation is overwhelming. They might want to avert their eyes or leave the room. In these cases, an audience member might even fail to note where the joke is. The joke-attempt has overstepped the mark and is now only experienced as a violation: there is no intersection between the violation and the psychological distancing. They are experiencing cringe overhang. This is illustrated in Figure 6:

The responses above are not a reflection of the moral rightness or wrongness of cringe comedy—they just show how differently the same set of violation-heavy jokes can be perceived by different members of any given audience.

Cringe comedians cannot readily adapt their polarising material for unforgiving audiences, because without the second-hand embarrassment and resulting maximised violation, they don’t have any jokes at all. If they added social psychological distancing to create the relief of additional distance from the characters’ plights, they’d cease to operate within their chosen subgenre. Cringe comedy has a smaller audience than other subgenres because the violation essential to its existence is too overpowering for some audience members to forgive.

Again, perception of the funniness of jokes is subjective. Comedy, like other artforms, is subject to audience taste—and few people would say that all art must appeal to everyone. Some people may not be strongly affected by embarrassment (second-hand or otherwise), and so may not view cringe comedy and Peep Show’s exploits as violations at all. Conversely, some people may find observational jokes on innocent-seeming subjects a strong violation because of their interest in that subject. Ryan Hamilton jokes about this phenomenon in his Netflix special, Happy Face (Raboy 2017, 41:00)—where a couple come up to him following his set about hot air balloons, claiming to be offended by the misrepresentation of their pastime. This seems to be a true story, but true or not, it shows how audience members can be made uncomfortable by the comedic treatment of subjects they value or norms they hold: comedic treatment which may seem perfectly innocent to other people. It seems that while comedy is subjective, subgenres that intentionally create stronger violations can expect to produce stronger negative responses in audience members who find those violations especially confronting.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have drawn on speech act theory and benign violation theory to explain the phenomenon of cringe overhang. Speech act theory explains cringe comedy’s illocutionary force as a subtextual invitation to laughter through second-hand embarrassment—which is why cringe comedy can be considered a failure when it only embarrasses the audience, but doesn’t provoke laughter. Benign violation theory explains cringe comedy’s method of inviting laughter as the production of non-socially psychologically distanced violations—in the form of second-hand embarrassment—accompanied by the smallest amount of benign to make it laughable. When a cringe comedy joke is experienced solely as a violation, the benign violation theory explains how cringe comedy fails to produce laughter: the joke is not benign-violation balanced. Having failed to achieve its desired perlocutionary effect of laughter, the joke’s violation instead causes the lingering discomfort of ongoing second-hand embarrassment.

If you were to take a bite out of an apple, only to find half a worm in it after you had swallowed, you would likely feel a sense of disgust—even some time later, the very thought of eating said worm is likely to produce remnants of that same disgust. This half-worm hanging on in the back of the audience member’s mind is cringe overhang.

Viewers who feel some second-hand embarrassment for Peep Show’s Mark Corrigan experience the violation as intended: sufficiently balanced with benign. Viewers who are stuck with a strong second-hand embarrassment struggle to laugh at his aborted proposal, chasing children with a metal pipe, and insulting his way out of an intimate conversation with his roommate’s ex-girlfriend. For these viewers, the violation—instead of producing laughter—provokes cringe overhang. Due to the risk of experiencing this undesirable phenomenon, cringe comedy is a subgenre that, due to its genre constraints, just isn’t for everyone.

Acknowledgments

For their many useful suggestions and valuable feedback, I would like to thank Richard Joyce and Edwin Mares; the 2023 conference convenors and attendees from both the Aesthetic Education through Narrative Art (Croatian Science Foundation) and International Society for Humor Studies organisations; Murray Smith, Oliver Double, Graeme A. Forbes and staff and students at the University of Kent; Katie Boyle; and especially the reviewers of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, Jesse, and Sam Bain, creators. Peep Show. Aired 2003-2015, Channel 4. 4DVD.

———, writers. Peep Show. Season 1, episode 1, “Warring Factions.” Aired September 19, 2003, on Channel 4. Directed by Jeremy Wooding, featuring David Mitchell and Robert Webb. 4DVD, 2006, DVD.

———, writers. Peep Show. Season 3, episode 4, “Sistering.” Aired December 2, 2005, on Channel 4. Directed by Tristram Shapeero, featuring David Mitchell and Robert Webb. 4DVD, 2006, DVD.

———, writers. Peep Show. Season 3, episode 6, “Quantocking.” Aired December 16, 2005, on Channel 4. Directed by Tristram Shapeero, featuring David Mitchell and Robert Webb. 4DVD, 2006, DVD.

Austin, John Langshaw. 1975. How to do Things with Words. The William James Lectures Series. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hye-Knudsen, Marc. 2018. “Painfully Funny: Cringe Comedy, Benign Masochism, and Not-So-Benign Violations.” Leviathan: Interdisciplinary Journal in English 2: 13-31. https://doi.org/10.7146/lev.v0i2.104693

Kant, Leo and Elisabeth Norman. 2019. “You Must Be Joking! Benign Violation, Power Asymmetry, and Humour in a Broader Social Context.” Frontiers in Psychology 10. Article 1380. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01380

Mayer, Annalina Valpuri, Frieder Michel Paulus, and Sören Krach. 2021. “A Psychological Perspective on Vicarious Embarrassment and Shame in the Context of Cringe Humor.” Humanities 10 (4). Article 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040110

McGraw, Peter, and Caleb Warren. 2010. “Benign Violations: Making Immoral Behaviour Funny.” Psychological Science 21 (8): 1141-1149.

McGraw, Peter, Lawrence E. Williams, and Caleb Warren. 2014. “The Rise and Fall of Humour: Psychological Distance Modulates Humorous Responses to Tragedy.” Social, Psychological, and Personality Science 5 (5): 566-572.

Raboy, Marcus, director. Ryan Hamilton: Happy Face. Comedy Dynamics. Aired August 29, 2017 on Netflix, https://www.netflix.com/hr-en/title/80184834

Sparrow, Alexander. 2024. “Humour and the Appearance of Authenticity in Live Comedy.” Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. https://doi.org/10.26686/wgtn.25304839

Veatch, Thomas C. 1998. “A Theory of Humor.” Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 11 (2): 161-215 https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.1998.11.2.161 199