Key words: endangered species, climate change, SDM, i-Ecology, Maxent, wildlife conservation INTRODUCTION

UVOD

Wildlife is a concept that includes not only wild animals but also all living and non-living elements that exist in the wild (Oğurlu 2001; Mol 2006). When considered in this context, it is clear that each element of wildlife is interconnected and that the living things can be directly or indirectly affected positively or negatively by any change in their environment (Noss 1990). Climate change may directly harm wild animals as a result of forced migration, behavioral changes, loss of prey, reproductive difficulties, etc. It may also harm animals indirectly with the change in their habitats (Walther et al. 2002; Root et al. 2003; Morin et al. 2021). While there may be many species affected by this negative situation, the species at risk of extinction are of greatest concern. The marbled polecat, one of these species, is an endangered species distributed in Türkiye and Europe according to the IUCN (2018).

The marbled polecat, a member of the Mustelidae family, is in the order of carnivores. Pine marten (Martes martes), beech marten (Martes foina), badger (Meles meles), Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), and ferret (Mustela nivalis) are other members of the family present in Türkiye. The marbled polecat was first described from the Rostov region of Russia (Güldenstäedt 1770). The marbled polecat has a small head and nose, a short muzzle, and remarkably large ears (Tez et al. 2001). The head and body length is between 26-35 cm, while the tail length is between 16 and 20 cm (Qumsiyeh 1996). It has a tail covered with long and bushy hairs. Dorsal fur is yellow and mottled with irregular brown or reddish spots (Gorsuch and Lariviere 2005). The marbled polecat was observed to change its fur between May and October (Tez et al. 2001). It has short legs and long claws. Therefore, its body is long and close to the ground.

The marbled polecat is nocturnal and crepuscular. Its diet consists of a variety of small mammals, including mice, voles, and rabbits, as well as birds, reptiles, amphibians, snails, insects, and fruits. It has been observed that the marbled polecat may attack small poultry (Gorsuch and Lariviere 2005; Randall et al. 2005). Although its eyesight is considered weak, its sense of smell is well-developed (Boukhdoud et al. 2021). Marbled polecats are adept climbers, although they primarily forage on the ground. They hiss in an aggressive manner and emit prolonged shrieks indicative of submission (Wund 2005). They are solitary except during the breeding season. The period of mating occurs between March and early June (Gorsuch and Lariviere 2005; Wilson and Mittermeier, 2009).

The marbled polecat range from China (Wang 2003), Romania (Raicu and Duma 1971), Palestine (Tristram 1866; Mallon and Budd 2011), Israel (Novikov 1962; Ben-David 1988; Werner 2012), Lebanon (Serhal 1985; Gorsuch and Larivière 2005), Syria (Peshev and Al-Hossein 1989), Iraq (Al-Sheikhly et al. 2022), Mongolia (Dulamtseren et al. 2009; Mitchell-Jones 1999; Shagdarsuren and Erdenejav 1988; Shiirevdamba 1997; Clark et al. 2006), Jordan (Amr and Disi 1988; Qumsiyeh 1993; Rifai et al. 1999), Bulgaria (Zidarova 2022; Ivanov and Spassov 2015; Mizumachi et al. 2017), Yugoslavia (Milenkovic et al. 2000), Persia (Farashi et al. 2018), Montenegro (Radonjić et al. 2022), Caucasus (Dzuyev and Tchamokov 1976), Saudi Arabia (Nader 1991; Harrison and Bates 1991; Corbet 1978), Uzbekistan (Sadikov 1983; Rozhnov et al. 2006; Rozhnov et al. 2008), Kazakhstan (Anonymous 1991), Russia (Heptner et al. 1967; Rozhnov 2001; Ognev 1931), Armenia (Sato et al. 2012), Azerbaijan (Rozhnov et al. 2008), Egypt (Saleh and Basuony 1988), Turkmenistan (Rozhnov et al. 2008), Macedonia (Kryštufek, 2000), Afghanistan, Georgia, Greece, Pakistan, Serbia to Ukraine (Abramov et al. 2016).

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, the marbled polecat was classified as a Vulnerable (VU) species (Abramov et al. 2016; Spassov and Spiridonov 1993; Lariviere and Jennings 2009). Abramov et al. (2016) reported that populations of the species have declined by 30% in the last ten years. The decrease in marbled polecat populations is thought to be due to the conversion of natural habitats to agricultural lands (Spassov 2007; Spassov & Spiridonov 2011), large area grazing of small cattle, desertification (Werner 2012; Abramov et al. 2016), hunting (Al-Sheikhly et al. 2015), reduced access to food sources (Krystufek 2000; Milenkovic et al. 2000), wildlife-human interactions (Milenkovic et al. 2000; Zidarova et al. 2022), road traffic (Abramov et al. 2016; Zidarova et al 2022) and the use of rodenticides in agricultural areas (Abramov et al. 2016).

The most basic objectives addressed in conservation biology are how to protect endangered species and to determine the planning in this context. Habitat loss and habitat fragmentation have been among the most important problems, especially in recent years (Fletcher et al. 2018; Evcin 2023; Yuan et al. 2024). Understanding the factors affecting species' habitats forms the basis for the conservation of threatened species (He and Hubbell 2011; Cheng et al. 2023). In this context, species distribution models (SDMs) are widely used in wildlife studies to understand the environmental requirements and geographic distributions of species (Brun et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). SDMs utilize observations of species occurrence or abundance and environmental data to predict species distributions across landscapes (Araújo et al. 2019; Mateo et al. 2019). They are valuable tools for gaining ecological insights, predicting species responses to environmental changes, and informing conservation and management decisions (Elith and Leathwick 2009). SDMs can assess the impacts of climate change on species distributions, identify suitable habitats for species, and understand the spatiotemporal patterns of human-wildlife conflict (Young et al. 2019; Fernandes et al. 2020; Fidino et al. 2022). By integrating presence-only data from sources such as citizen science projects and social media, SDMs can provide valuable information about species-habitat relationships and abundance across space and time (Fidino et al., 2022; Mohankumar et al., 2022).

The maximum entropy approach (MaxEnt) has been widely used in wildlife studies (Valavi et al. 2021; Ahmadi et al. 2023; Farashi and Noughani 2023). It is a machine learning method that uses the principle of maximum entropy to model species geographic distribution with presence-only data (Phillips et al. 2006). Additionally, SDMs rely on selecting relevant predictors, considering scale, and handling environmental and geographic factors, which can influence model realism and robustness (Elith and Leathwick 2009). Incorporating ecological theory and addressing these challenges is important for advancing the field of SDMs in wildlife studies (Guisan and Thuiller, 2005).

Recently, social media have become an increasingly important source of information (Toivonen et al. 2017). Social media platforms provide a vast amount of information that can be used for wildlife studies and conservation efforts (Di Minin et al. 2015). By analyzing text, images, videos, and audio associated with social media posts, researchers can gain insights into human-wildlife interactions, species distributions, and the impacts of environmental changes on wildlife (Jarić et al. 2020; Wright et al. 2023).

I-Ecology (Jarić et al. 2020), also known as internet ecology, is a field of study that utilizes social media data to understand ecological patterns and processes. Social media data is a valuable information source for conservation culturomics and i-ecology. It can provide insights into human-nature interactions, ecological patterns, and processes (Tenkanen et al. 2017; Toivonen et al. 2019; Di Minin et al. 2021). Conservation culturomics has been used to analyze public interest in charismatic or invasive species, understand human-wildlife conflict, and examine wildlife trade. Social media posts documenting species occurrences have also been used to gather information about their distributions (Dylewski et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2023).

In Türkiye, the marbled polecat has become increasingly habituated to human activity in agricultural areas. This has resulted in a rise in human-wildlife conflict, with local communities resorting to the killing of the marbled polecat as a means of protecting poultry and agricultural products (Capitani et al 2015; Chynoweth et al 2015). This situation further endangers the existence of this species, which is at risk of extinction. Unfortunately, we do not have clear information about the number of individuals of this species because inventory studies in Türkiye mostly cover large mammals and trophy species. In addition, wildlife studies are quite low and insufficient (Evcin et al., 2019). Therefore, no studies have been conducted on the species, the population density is unknown, and there is no action plan for the protection and management of the species. However, it is known that the marbled polecat is distributed in Türkiye, but the distribution points are not up-to-date. For this reason, new distribution areas of the species should be determined for conservation and development studies related to the species.

In this study, the location data was collected for the marbled polecat, which is endangered and distributed in Türkiye, but for which there is no up-to-date information about its distribution areas, social media tools, past literature records, data obtained from the nature conservation and national parks directorate. As a result of the research, new distribution places of the species were determined using the filtered records and using these data. Potential distributions of the species were determined by using ecological modeling with current and future climate scenarios.

MATERIJAL I METODE

The flow chart determining the current and future potential distribution area of the marbled polecat depending on various climate change scenarios is given in Figure 3.

Figure 1. Flow chart

Slika 1. Dijagram toka

Occurrence data - Podaci o pojavljivanju

The study material consists of identified individuals belonging to the marbled polecat species distributed in Türkiye. Within the scope of the study, literature review, searching GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) (URL-1 2023) and TRAMEM (Anonymous Mammals of Turkey) (URL-2 2023) database, field data of the General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks (Figure 2), news about the species in social media (YouTube videos, posts on Facebook and Instagram) were filtered. In order to confirm the accuracy of the data, the coordinates and photographs belonging to the species were compared together and the same data were detected and deleted. In addition, the owners of the photos and videos of the records on social media were contacted as much as possible, and the data that ensured the existence of the species were used. In the light of the data obtained, 103 occurrence point records of the marble polecat in Türkiye are given in Table 1 and shown on the map in Figure 3.

Figure 2. The marbled polecat in thanatosis posture in Kastamonu region, Türkiye

Slika 2. Šareni tvor u položaju tanatoze u regiji Kastamonu u Turskoj

Table 1. Records of the marble polecat in Türkiye

Tablica 1. Podaci o šarenom tvoru u Turskoj

Figure 3. New presence records of marbled polecat in Türkiye

Slika 3. Novi nalazi o prisutnosti šarenog tvora u Turskoj

Bioclimate data - Podaci o bioklimi

Nineteen (19) climate variables from WorldClim database v2 (Hijmans et al., 2005) at a spatial resolution of 30 arc-second (ca. 1 × 1 km) were obtained as predictors to model the potential environmental niche of marbled polecat (Table 2). SSP 2-4.5 (minimum emission hypothesis) and SSP 5-8.5 (maximum emission hypothesis) were chosen in our study. HadGEM3-GC31-LL climate model was obtained from WorldClim (www.worldclim.org) (Hijmans et al., 2005) database under both scenarios over the periods 2041–2060, 2061–2080 and 2081-2100. HadGEM3-GC31-LL is a climate model produced by the Met Office Hadley Centre (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk), based on the atmospheric component of the current Earth System Model. HadGEM3-GC31-LL consistently performs well for both precipitation and temperature extremes on Eurasian and global scale (Nishant et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2023).

Table 2. List of 19 bioclimatic variables used in model development

Tablica 2. Popis od 19 bioklimatskih varijabli korištenih u razvoju modela

In ecological niche modeling, it is crucial to exclude highly correlated variables to improve model performance and interpretability. High multicollinearity among predictor variables can inflate the importance of correlated variables, leading to biased and less reliable model outputs (Graham 2003; Dorman et al. 2013).

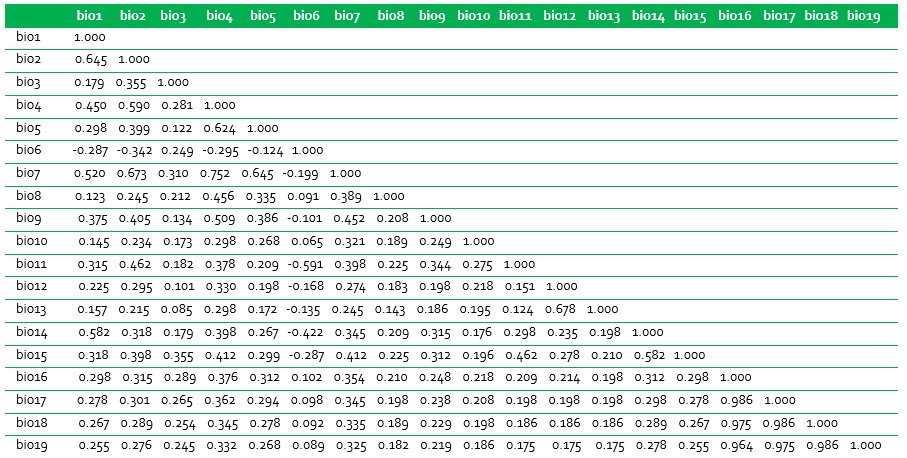

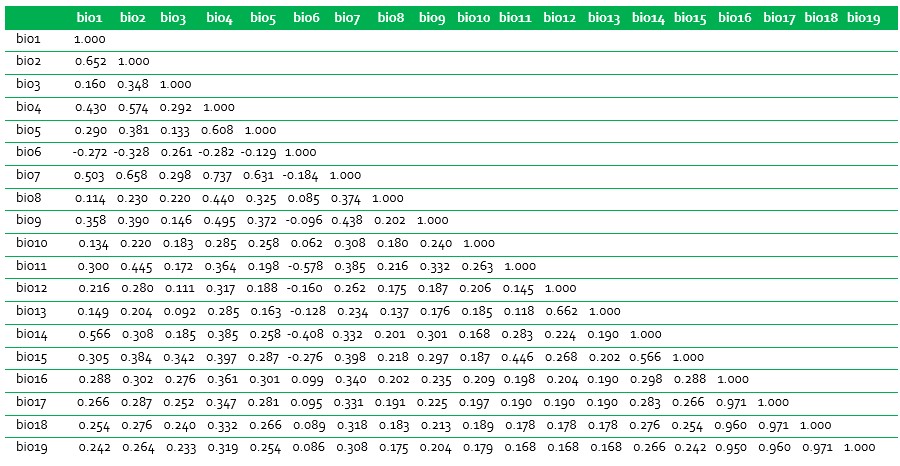

According to Dorman et al (2013), the presence of multicollinearity can result in overfitting, where the model captures noise rather than the true ecological signal. By excluding highly correlated variables, the model ensures a more robust estimation of species-environment relationships, thereby enhancing the model's predictive power and ecological relevance. For this purpose, Pearson correlation analysis was applied to prevent the multicollinearity problem that may occur between the 19 bioclimatic variables. As a results of the analysis (Tables 3 and 4), variables with a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) value of ±0.7 and above were removed from the model and the multicollinearity problem was solved. According to the results, bio2, bio3, bio6, bio11, bio14, bio15 and bio18 were selected.

Table 3. Correlation matrix for selecting bioclimatic variables (SSP 2-4.5 scenario)

Tablica 3. Korelacijska matrica za odabir bioklimatskih varijabli (scenarij SSP 2-4.5)

Table 4. Correlation matrix for selecting bioclimatic variables (SSP 5-8.5 scenario)

Tablica 4. Korelacijska matrica za odabir bioklimatskih varijabli (scenarij SSP 5-8.5)

Habitat suitability model development - Razvoj modela prikladnosti staništa

Maximum entropy (MaxEnt) modeling approach was used to build potential areas for marbled polecat. MaxEnt models aim to estimate the potential distribution of a species with spatial distributions of species by using environmental variables determining the distribution of maximum entropy (Phillips et al. 2006).

MaxEnt modeling is a widely used machine learning method for modeling geographic distributions of species with entity data only. It is a general purpose method with a simple and precise mathematical formulation and is well suited for species distribution modeling. It has been stated that MaxEnt modeling can better distinguish between suitable and unsuitable areas for the species and provide reasonable estimates of species ranges (Phillips et al. 2006; Phillips et al 2009). In addition, MaxEnt modeling involves making decisions about the structure of the model, taking into account the characteristics of the type and the data (Elith et al. 2010). Presence-only data, commonly used in species distribution modeling, have special implications for modeling distributions. MaxEnt takes these results into account and allows species distributions to be modeled based on presence records only (Phillips and Dudík 2008; Elith et al. 2010).

Model validation and analysis - Validacija i analiza modela

The validation of the model was conducted using the jackknife validation approach (Sharma et al. 2018; Zhen et al. 2018). To perform the validation, 75% of the location point data for each species were used as training data, while the remaining 25% were used for model validation. The MaxEnt model was utilized, and the output format was set to logistic. The model was run with 10 replicates to obtain the best possible results. In order to prevent unnecessary variables from affecting the success of the model, variables below 5% were removed and the models were re-run with the remaining variables. A regularization factor of 1 was employed. The outputs were averaged and converted into raster format using ArcMap software. To assess the performance of the model, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showing the AUC values of the model were used (Phillips et al. 2006; Pearson et al. 2007).

REZULTATI

Social media research - Istraživanje društvenih mreža

In the manual social media search, through searches on YouTube, 30 species data were reliably obtained with photo and video evidence. Coordinate information was checked to ensure that there were no similarities in the data obtained in the screening studies carried out through GBIF and TRAMEM databases, and the TRAMEM database was taken as a basis because it was more comprehensive, with 41 species data records obtained. As a result of detailed literature study and recording of scans obtained from the General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks, a total of 103 locations (Table 1) where marbled polecat was observed were determined in Türkiye. According to the results in Table 1, it was observed that the marbled polecat data were distributed in the west, south and central Anatolia region of Türkiye.

Habitat suitability models - Modeli prikladnosti staništa

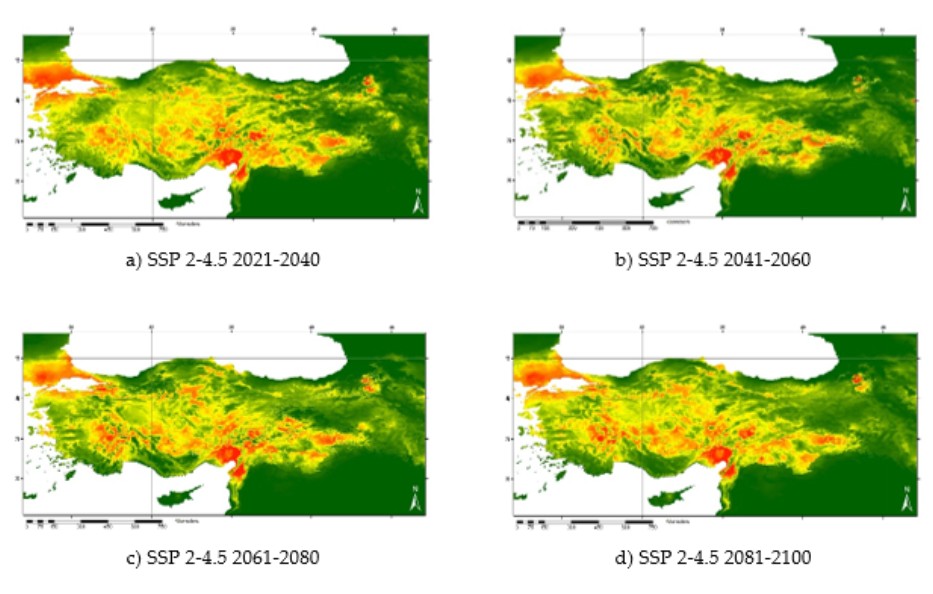

Marbled polecat was modeled for the periods 2021-2040, 2041-2060, 2061-2080 and 2081-2100 (HadGEM3 SSP 2-4.5 and SSP 5-8.5) and 8 models were created. When the results were evaluated, habitat suitability model performance was highly reliable (Phillips et al. 2006). AUC values of all models were found to be between 0.89 and 0.91 (Table 5). The ROC value of the habitat suitability model was 0.897 for SSP 2-4.5 2021-2040, 0.908 for SSP 2-4.5 2041-2060, 0.901 for SSP 2-4.5 2061-2080, 0.899 for SSP 2-4.5 2081-2100; 0.912 for SSP 5-8.5 2021-2040, 0.899 for SSP 5-8.5 2041-2060, 0,896 for SSP 5-8.5 2061-2080, 0,891 for SSP 5-8.5 2081-2100. According to this result, it has been determined that the model was found to be successful (Baldwin 2009).

Table 5. AUC values of climate models

Tablica 5. AUC vrijednosti klimatskih modela

The habitat suitability map for the marbled polecat is given in Figure 4. Habitat suitability is represented from lowest suitability (in green) to highest suitability (in red). When the model map obtained for the SSP 2-4.5 scenario is examined (Figures 4a-d), it is seen that marbled polecat is densely distributed in the Marmara, Mediterranean, Central Anatolia and Southeastern Anatolia regions. However, it was determined that there was a visible decrease for the Marmara region in the following periods. It was determined that the Mediterranean region is the place where marbled polecat preserves its distribution best. It can be seen that the distribution remains constant in the Southeastern Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia and Aegean regions, while the distribution decreases in the Central Anatolia and Black Sea regions.

Figure 4. Potential distribution map of the marble polecat in Türkiye with maximum entropy approach (2021-2100)

Slika 4. Karta potencijalne distribucije šarenog tvora u Turskoj s metodom maksimalne entropije (2021-2100)

When the model map obtained for the SSP 5-8.5 scenario is examined (Figures 4e-h), there is a similarity with the optimistic scenario. However, differently, it is seen that the density has increased slightly in the Black Sea region, but the density has decreased in other regions. Likewise, it seems that the Mediterranean region is the place where marbled polecat best protects its distribution.

Marbled polecats were identified throughout most of Türkiye (Wright et al., 2023). The striking point in the 8 maps obtained using current and future scenarios is that Thrace, Marmara region and Mediterranean region are the places with the highest distribution.

Variable contributions and permutation importance were obtained as the result of models. Mean variable contributions and permutation importance of models were calculated (Table 6). According to the jackknife test results, for SSP 2-4.5 scenario bio14 (Precipitation of Driest Month), bio15 (Precipitation Seasonality), bio6 (Min Temperature of Coldest Month), bio3 (Isothermality), bio11 (Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter); for SSP 5-8.5 scenario bio14 (Precipitation of Driest Month), bio15 (Precipitation Seasonality), bio6 (Min Temperature of Coldest Month), bio2 (Mean Diurnal Range), bio18 (Precipitation of Warmest Quarter) were identified as the most important bioclimatic variables contributing to potential distribution model of marbled polecat. The variable with the highest value for both models was bio14.

Tablica 6. Doprinosi srednjih varijabli i važnost permutacije modela

The predicted suitability was classified into very low, low, moderately and high probability classes based on classification by Khafaga et al. (2011). Change in the suitability of marble polecat habitats are given in Table 7. The results demonstrate the alterations in the suitability of the polecat's habitat at different time intervals in accordance with the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Table 7. Change in the suitability of marble polecat habitats in Türkiye according to climate change scenarios (2021-2100)

Tablica 7. Promjene u prikladnosti staništa šarenog tvora u Turskoj prema scenarijima klimatskih promjena (2021-2100)

The SSP 2-4.5 scenario for marbled polecat indicates that the area of suitable habitat for the species in question has undergone a number of changes over time. The area of very low suitable habitat has decreased, while that of low suitable habitat has tended to increase. The area of medium suitable habitat has increased in some periods, but has generally decreased. Finally, the area of high suitable habitat has tended to decrease over time. The SSP 5-8.5 scenario for marbled polecat revealed that the area of suitable habitat exhibiting the lowest suitability showed a continuous decrease. In contrast, the area of suitable habitat exhibiting the lowest suitability showed an increasing trend over time. The area of suitable habitat exhibiting the lowest suitability showed a decrease, while the area of suitable habitat exhibiting the highest suitability showed an increase. In general, both scenarios indicated a decrease in the high suitable habitat areas of marbled polecat, while an increase was observed in the low and medium suitable habitat areas. Consequently, it can be posited that the optimal habitat for the marbled polecat in Türkiye is distributed in the middle, northwest, southwest, and southeast. This situation indicates that there may be significant alterations in the habitat suitability of the marbled polecat in the future. It can be posited that these changes are the consequence of the combined effects of climate change and other environmental factors.

RASPRAVA

Climate change can alter the habitats of endangered species, causing expansion or contraction (Ebrahimi et al. 2021). This may affect the distribution and survival of the marbled polecat. In this study, the potential distribution areas of marbled polecat in certain periods were determined using current and future climate scenarios. The marbled polecat is typically found in open grasslands and steppes, where it can secure adequate cover and prey. These habitats provide the essential resources for hunting and shelter. Additionally, it inhabits semi-arid and arid regions, particularly in areas where there is sparse vegetation and burrowing animals that serve as prey. When both optimistic and pessimistic scenarios are examined, bio14 and bio15 variables representing drought for marbled polecat provide the highest contribution. Climate change is likely to significantly impact the distribution of marbled polecat through changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. As a result of climate change, the increase in temperatures and decrease in precipitation, marbled polecat is affected by drought in various aspects. The most important of these is dehydration, which is of vital importance. Water is the basic source of life for all living things. It is also indispensable for wild animals to cool off in extreme heat. With the decrease in rainfall, not only wild animals but also plant communities and soil structure will be affected. The weakening and thinning of vegetation causes the habitat of marbled polecat to narrow and the shelter places to decrease.

The effects of climate change are becoming increasingly evident in Türkiye. In particular, increasing temperatures, longer drought periods and changes in precipitation regimes have been observed. These changes create various effects on agriculture, water resources and ecosystems (Öbük and Sınmaz 2024). Drought conditions can have significant impact on the distribution of marbled polecats. As a semi-fossorial species, marbled polecats rely on burrows for shelter, reproduction, and predator avoidance (Sheffield and Thomas 1997). During periods of drought, soil moisture levels decrease, causing the soil to harden and compact (Tietjen et al. 2017). This makes burrowing and maintaining existing burrows more difficult for marbled polecats, potentially leading the burrow to collapse (Reichman and Smith 1990). Droughts can also reduce food availability for marbled polecats. Their primary prey consists of small rodents and birds which depend on vegetation and insects for food (Corbet 1978). Prolonged drought can cause declines in vegetation growth and insect populations, resulting in lower prey abundances for marbled polecats (Jaksic and Lima 2003). As marbled polecats must consume up to 50% of their body weight in prey daily, food limitation during drought likely forces them to shift their distribution to areas with greater prey availability (Sheffield and Thomas 1997). In summary, drought impacts marbled polecats through decreased burrowing capability due to soil compaction and lower food availability due to declines in primary prey populations. These factors likely force marbled polecats to shift their distribution during periods of drought, concentrating in areas that provide sufficient shelter and prey to meet their ecological requirements (Reichman and Smith 1990; Tietjen et al. 2017).

It is accepted that the potential distribution areas for the marbled polecat obtained using climate change scenarios do not actually represent the actual distribution areas and are determined by estimation. As a result of these predictions, it is estimated that the habitat of the marbled polecat will increase in some regions and decrease in others due to climate change in the coming years. Additionally, its distribution area is expanding towards the north (the Black Sea region) depending on the temperature. In order to prevent this endangered species from facing possible extinction due to the effects of climate change, importance should be given to wildlife planning and conservation studies.

ZAKLJUČCI

In this study, we determined the potential distribution areas of the marbled polecat species, which is an endangered, difficult to encounter and at the same time little-studied Mustelidae in Türkiye, using social media data, various databases and literature studies. For this, we applied the MaxEnt method using good and bad climate change scenarios and 19 bioclimate variables. Thus, we obtained the potential distribution map of the marbled polecat according to scenarios for current and future years. Modeling results contributed to the determination of suitable habitats for the species, allowing us to comment on the potential distribution area of the species for current and future years as a result of climate change scenarios. Climate change, which continues to show its effects today, will also affect the distribution of the marbled polecat over time. The results showed losses and gains in the species' habitat according to optimistic and pessimistic climate change scenarios. In some regions of Türkiye, there will be narrowing and decreasing of habitat, while on the contrary, there will be an increase and expansion of the habitat, for example in the Black Sea region. These endangered species are a source of biodiversity for every country where they are encountered. Preserving this faunal richness is also important for wildlife populations. For this, countries need to take protection measures and raise public awareness to prevent the extinction of marbled polecat and other endangered species. In order to improve the adverse conditions caused by climate change and prevent the extinction of endangered species, it is important to support and develop wildlife conservation studies, take precautions, effectively carry out wildlife management and planning, ensure sustainability and raise public awareness.