Problems in the nomenclature of map projections

To identify map projections, usually short names are preferred. Who would like to write such awkward names like 'equal-area pseudoconic projection with equidistant parallels' instead of 'Bonne projection' or 'equal-area flat-polar pseudocylindrical with sinusoidal meridians' instead of simply 'Eckert VI' or 'Kavrayskiy VI' (Lee, 1944). Even the last example shows that these 'descriptive' names based on the graticule and the distortions of the projections would be ambiguous, as the Eckert VI and Kavrayskiy VI projections are very similar but distinct mappings.

However, naming maps after its developers has its serious drawbacks. For example, Kavrayskiy was not the first to publish the Kavrayskiy VI projection (Snyder, 1993), exactly the same map is found in the dissertation of Wagner, albeit a few years earlier. Bonne was not the inventor of the Bonne projection, as it was developed gradually during the early modern age based on the Ptolemy II map. There are even wilder cases like sinusoidal projection, which is also called as 'Mercator equal-area'. Mercator is probably not related to it at all, as we find this mapping in the Mercator Atlas only decades after his death, when the atlas was published by Hondius (Snyder, 1993). At least, this map projection did exist at the age of Mercator, as we find it on a world map published in 1570 by Cossin.

In this paper, we will consider the authorship of two globular maps named after Apian. His authorship on the Apian II projection has never been questioned to the best knowledge of the author.

Apian and 'his' map projections

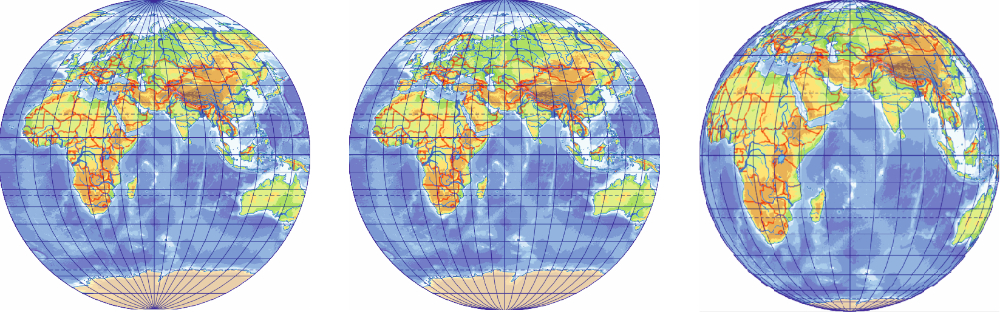

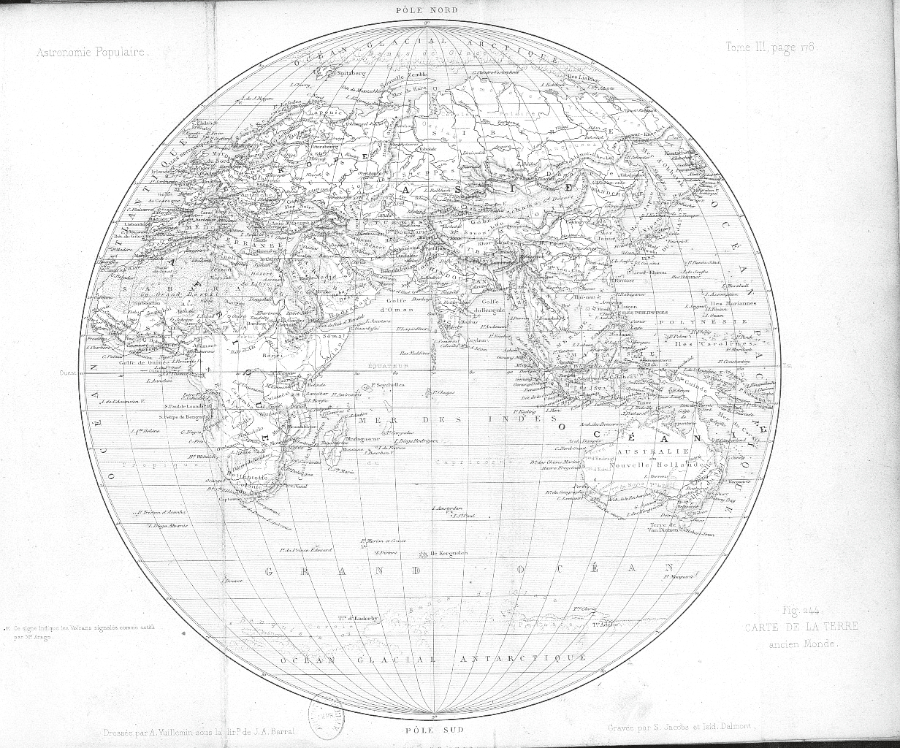

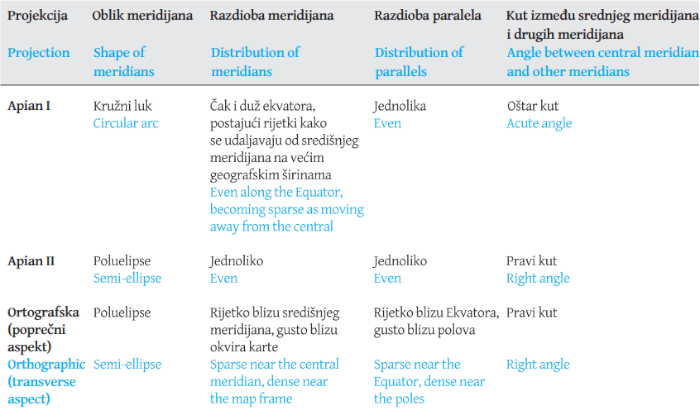

It is a common belief in the cartographic community that the German cartographer Peter Bienewitz, known as Petrus Apianus or simply as Apian, is the author of two globular map projections (Snyder, 1993;Wagner, 1962). Both projections show the hemisphere in a circle, and parallels are horizontal straight lines dividing the central meridian in proportion to their latitude. Meridians divide the Equator in proportion to their longitude. However, meridians are arcs of circles in the Apian I projection, while they are mapped to semi-ellipses in the Apian II projection (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The Apian I, Apian II, and transverse orthographic projections (in reading order) / Slika 1: Apian I, Apian II i poprečna ortografska projekcija (slijeva nadesno)

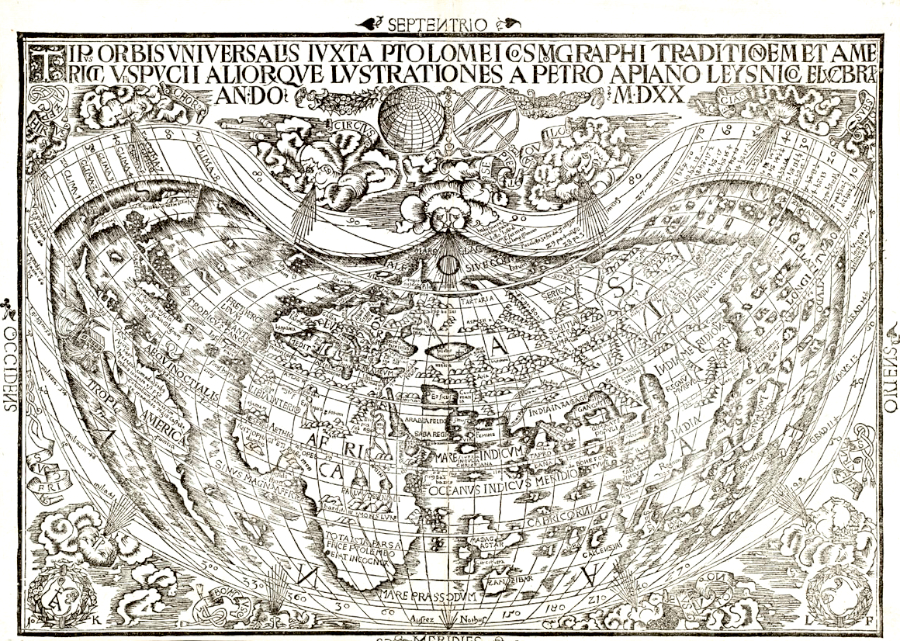

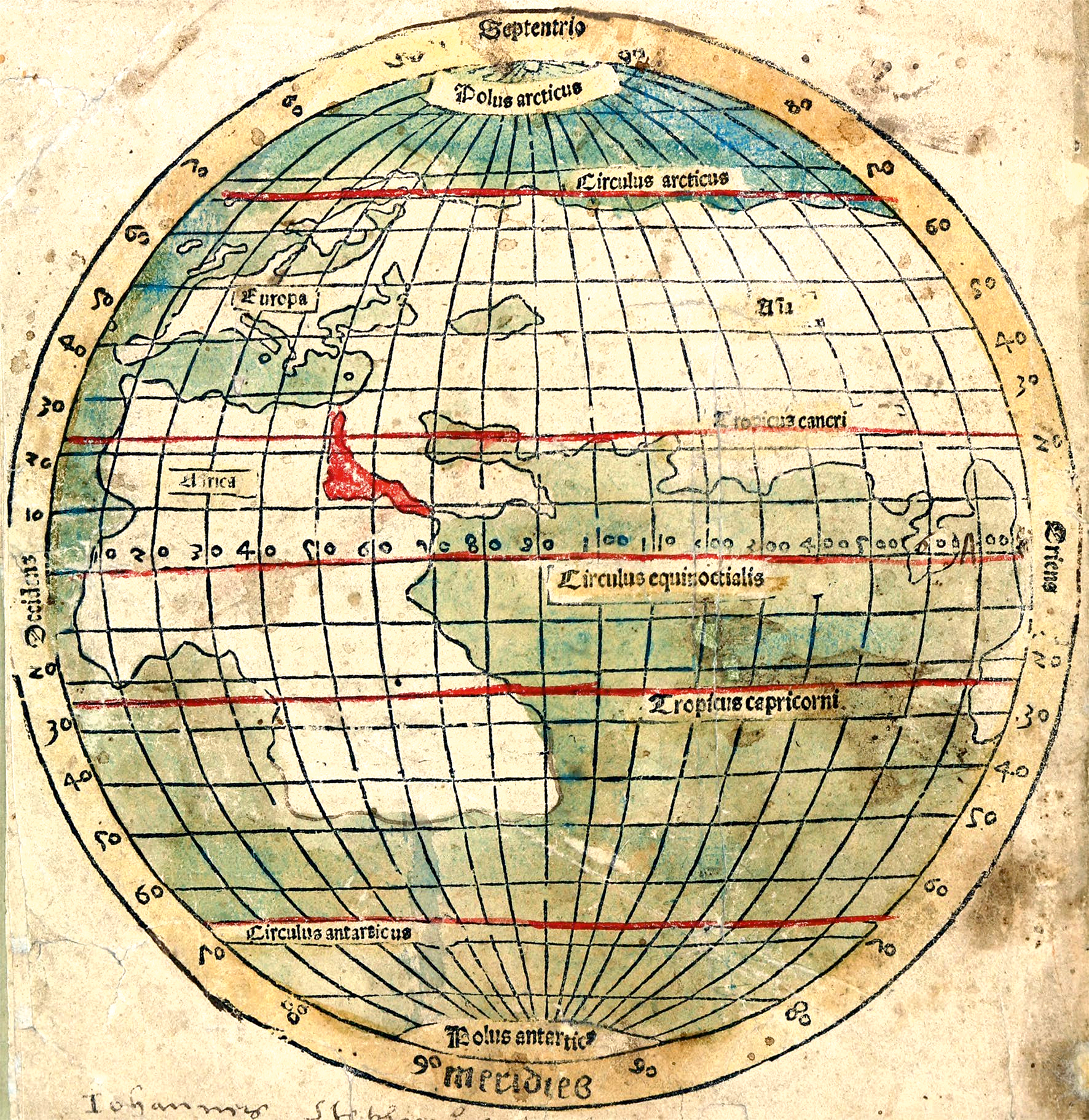

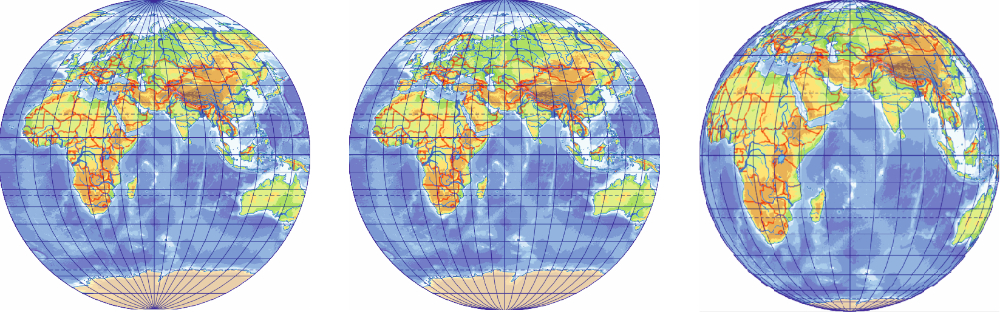

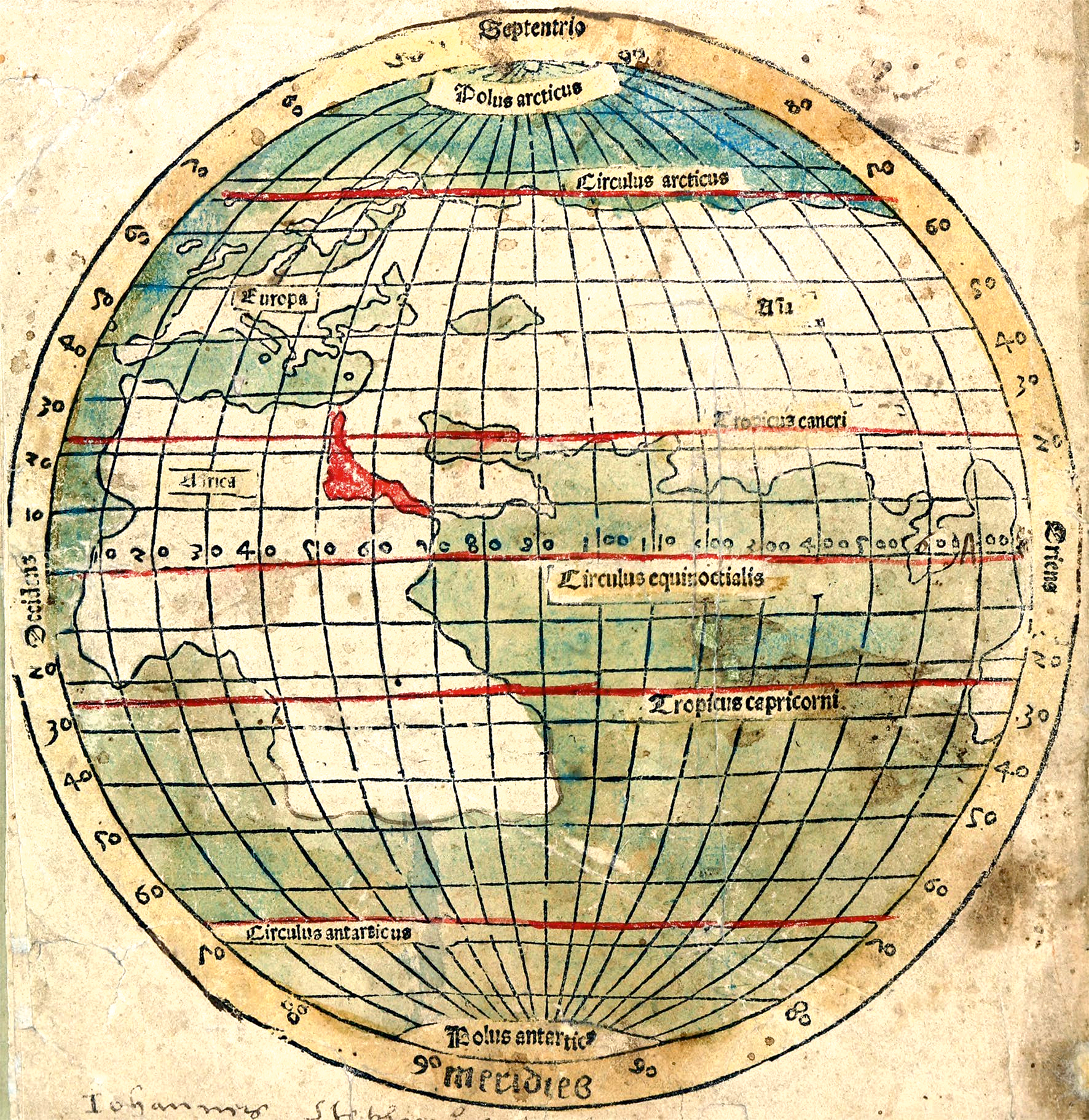

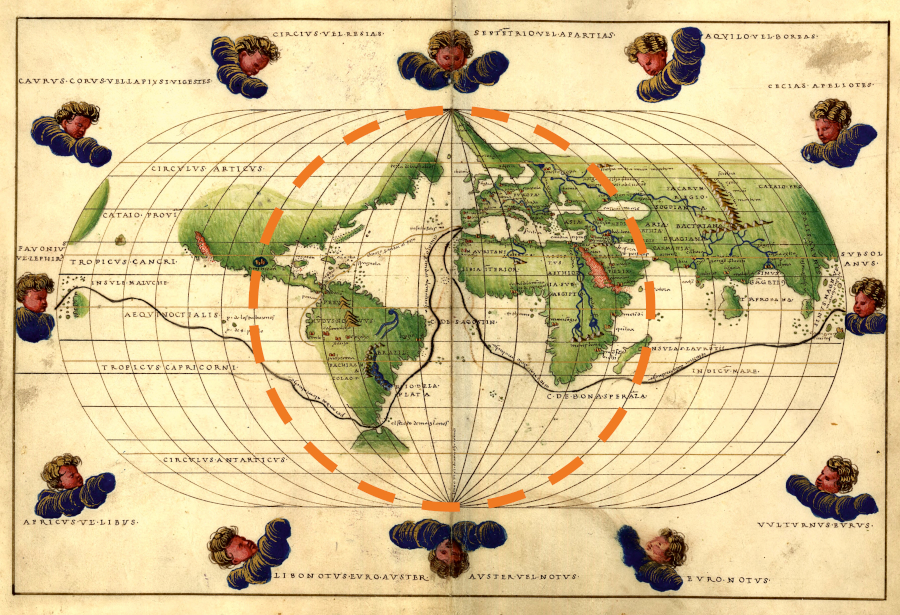

The authorship of Apian can be questioned for both map projections. The Apian I projection appears on maps drawn when Apian was very young. There are no maps known in the Apian II projection before the 19th century, and this 300-year long silence is also suspicious. In fact, Apian did create a world map, but not a globular one, rather a pseudoconic one. His 1520 map (which is usually attached to his later books) shows the Earth in a projection that can be seen as a transition between the Ptolemy II and the Bonne projections, very similar to the map of Waldseemüller (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The map of Apian (1520) / Slika 2: Apianova karta (1520)

Comparison of similar mappings

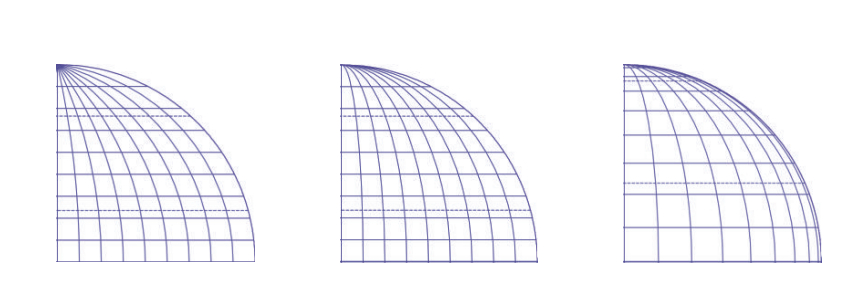

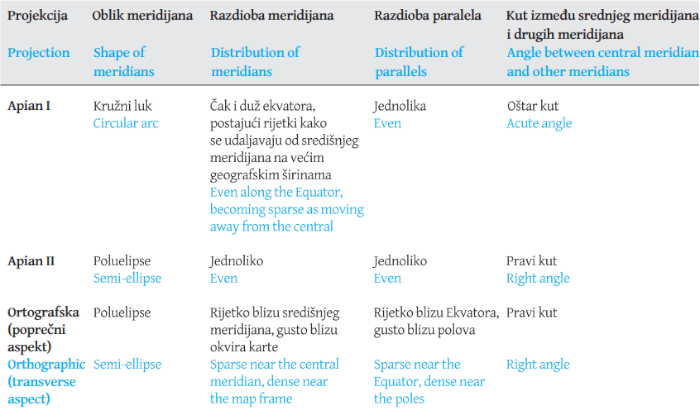

Some map projections seem to be identical for a superficial viewer. Telling these map projections apart needs a little practice and knowledge about where to look for minor differences. This is exactly the case for the two Apian projections. For example, all parallels have a constant scale in the Apian II projection, but meridians do not divide parallels of the Apian I projection evenly (except the Equator): they are dense near the central meridian and sparse far from it. It is visible mostly at high latitudes. In the Apian I projection, bimeridians make an acute angle with the central meridian at the pole, but they are smooth curves perpendicular to the central meridian in the Apian II map.

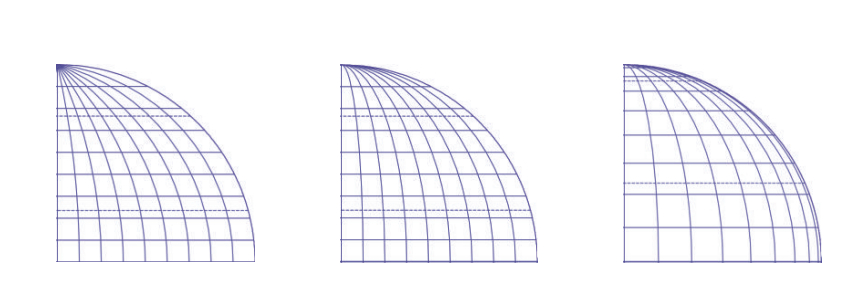

Before going on, we must examine a third, very similar map projection: the orthographic one. Being an azimuthal projection, one may not even consider it when straight parallels are detected. However, in the transverse aspect, the orthographic projection results in straight parallels, and it maps meridians to semi-ellipses, so it looks like a pseudocylindrical projection. Furthermore, it displays the hemisphere in a circle, so it can also pretend to be a globular map. To prevent misidentification, we must observe that in the transverse orthographic projection, the central meridian is not equidistant: parallels are dense far away from the Equator. Unlike the Apian II projection, its meridians are not spaced evenly, they are sparse near the central meridian, and dense near the frame. A comparison of these map projection is summarized inTab 1 andFig. 3.

Figure 3: Graticule of the Apian I, Apian II, and transverse orthographic projections (in reading order) / Slika 3: Karografska mreža projekcija Apian I, Apian II i poprečne ortografske projekcije (sliejva nadesno)

Table 1: Comparison of globular projections with straight parallels / Tablica 1: Usporedba globularnih projekcija s ravnim paralelama

Origins of the Apian I projection

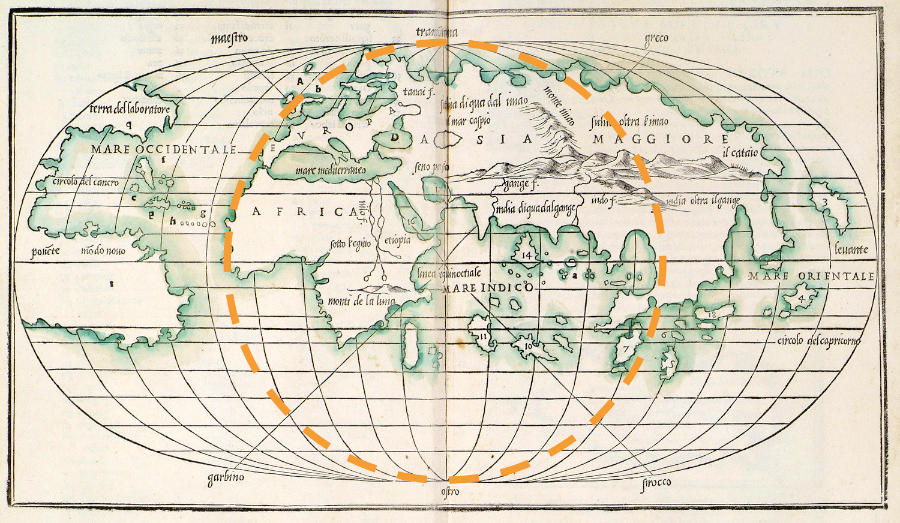

The first known occurrence of the Apian I map projection dates to 1505 (Fig. 4). It was found in the University Library of Rostock.Pápay (2021) examined the history and the background of this map and concluded that the author of the map was presumably Amerigo Vespucci, the eponym of America. Pápay also argues that this map was created by Vespucci much earlier, as he mentions it and its content in a letter written in 1500. At this time, Apian was only five years old, so we can safely conclude that it is quite unlikely that Apian was the original inventor.

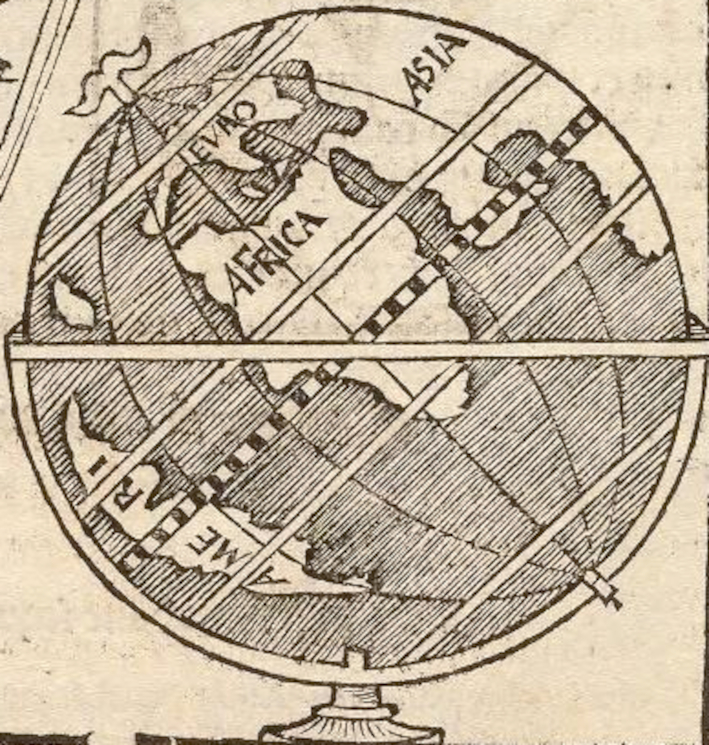

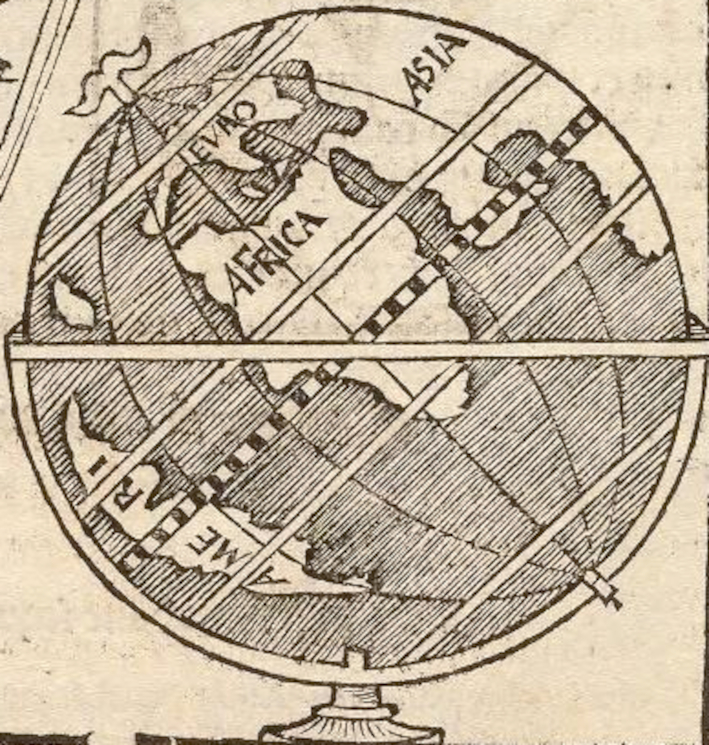

Studies claiming the authorship of Apian usually refer to his book (Apian, 1524). In this book, we find a classical renaissance cosmography based on the work of Ptolemy. There is no mention of any new map projection in it. There is only one tiny illustration depicting a globe, the graticule system of which does show some slight resemblance to the Apian I projection (Fig. 5). However, this sketch is rudimentary, considering it as a 'map projection' seems to be a bit arbitrary. We should also mention that all other illustrations of globes in this book use curved parallels, so it might be that this coincidence is accidental.

Figure 4: The map of Vespucci using the Apian I projection in 1505. (Pápay 2021) / Slika 4: Karta Vespuccija pomoću projekcije Apian I iz 1505. godine (Pápay 2021)

Figure 5: The sketch of a globe by Apian (1524) / Slika 5: Apianova skica globusa (1524)

Nevertheless, it is clearly visible from the figures that meridians are printed as arcs of circles in both Vespucci's map and Apian's sketch. Even the aformentioned pattern of dense meridians near the central meridian and sparse meridians far away from it can be clearly measured. This is contrary to the statements ofPápay (2021), who claims that meridians of Vespucci's map are equal-spaced ellipses. Pápay tries to reconstruct a possible construction method of Vespucci's map. However, the construction method he describes would result in the Apian II projection (as discussed in the next section), while the map rather shows the properties of the Apian I projection.

Thus, to our best knowledge, the inventor of the Apian I map projection is Amerigo Vespucci, and he invented it around 1500. Apian might have heard this graticule, as we see a rudimentary sketch of a globe similar to this projection. However, this evidence is weak, so it is still possible, that Apian might have used the map projection named after him unintentionally.

Origins of the Apian II projection

The transverse orthographic projection has been known by the time of Apian. He even displays a full-page illustration in his book featuring it. However, we find no mention of the Apian II projection neither in the Cosmographica (Apian, 1524) nor in his other books.

At the early 16th century, map-makers usually copied each other's maps, and constructed new map projections only occasionally. Therefore, if the Apian II projection were invented by Apian or by one of his contemporary map-makers, then it would be very unlikely that we would not find any map in it. We indeed find a handful of maps utilizing the Apian I projection. Examples include Tramezzino's 1554 map. However, no map is known in the Apian II projection.

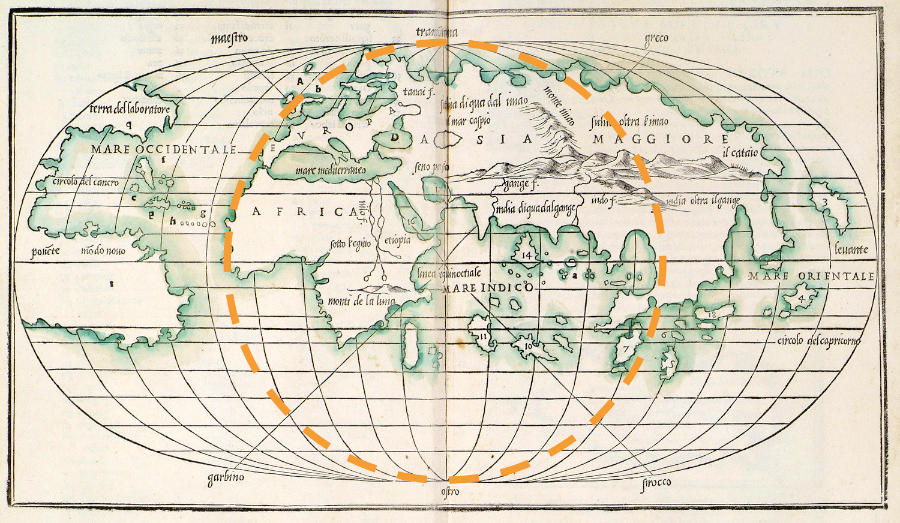

We do find some oval world maps created at this time. Nevertheless, they are not in the Apian II projection: meridians are not exactly semi-ellipses, but some arbitrary oval lines. Meridians are also not spaced evenly in these oval maps. One may suppose that this difference is an error of print. In fact, the central meridian of the Vespucci map (Fig. 4) is also not perfectly equidistant, some minor deviations do occur. Was not, for example, the Bordone map (Fig. 6) intended to be the projection we know as the Apian II projection?

At the early modern age, graticule networks were constructed using a straightedge and a pair of compasses. The Apian II projection can be constructed quite easily. We follow the reconstruction ofPápay (2021), in which he calls the representation of hemisphere in the Plate Carrée projection as a square map. Draw such a square map, then draw a circle centred on the intersection of the Equator and the central meridian trough the two poles (this will be the meridians ±90° from the central meridian). From the original square map, we keep only the parallels and the central meridian. Divide all parallels of the square map equidistantly between the central meridian and the perimeter of the circle (you can continue plotting these distances beyond the circle if a world map is needed). Draw the meridians by connecting the points marked on the parallels.

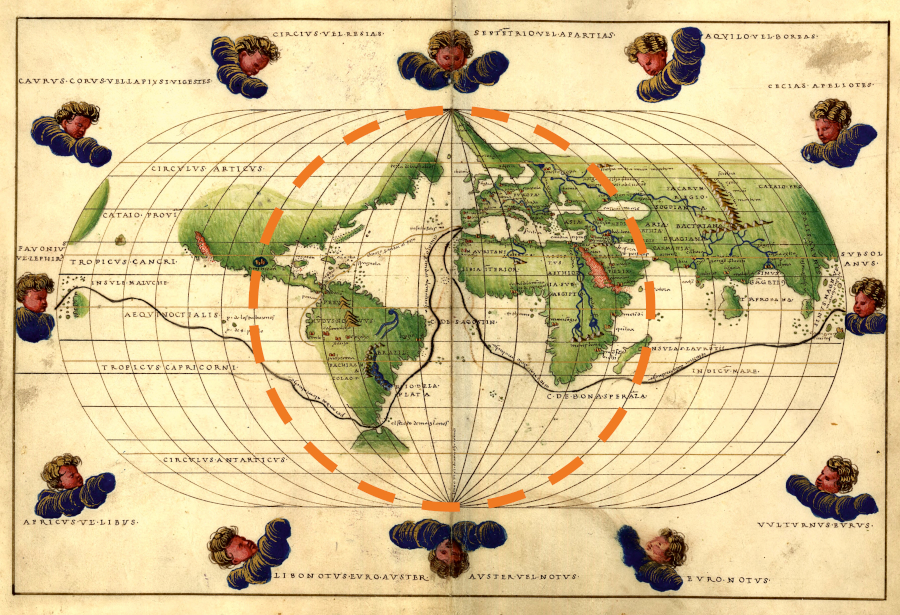

The result of the process above does not produce perfect ellipses for all meridians, just something very close to it. However, the bimeridian ±90° from the central meridian should be a perfect circle, so we can check this to evaluate if early oval maps can be regarded as examples of the Apian II projection. InFig. 6, we see that neither of the meridians follow a circular shape.Fig. 7 is shown as a comparison. It is easily observed that much better accuracy could have been achieved even in the 16th century if a circular bimeridian was intended (this map is in the Ortelius projection, an extension of the Apian I projection).

Figure 6: The meridians ±90° from the central meridian are not circles in the map of Bordone (1547). / Slika 6: Meridijani ±90° od središnjeg meridijana nisu kružnice na Bordoneovoj karti (1547).

Figure 7: The meridians ±90° from the central meridian are perfect circles in the map of Agnese (1544). / Slika 7: Meridijani ±90° od središnjeg meridijana savršene su kružnice na Agneseovoj karti (1544).

In the next centuries, oval world maps became 'outdated', we may only find a few examples of the Ortelius projection, giving precedence to the 'fashionable' Mercator projection. Hemisphere maps were drawn in transverse azimuthal or in Nicolosi projections, we find no candidates to be a development upon the Apian II map. There are no known similar maps from this era, with the exception of Mollweide map invented at 1805. Apparently,Mollweide (1805) has not been aware of the very similar Apian II projection, as he does not mention it in his paper.Fournier (1643) also developed a handful of globular maps. Although he uses elliptical meridians, he does not list the Apian II projection, which is suspicious, as the Apian I projection is mentioned as a base work. (In fact, Fournier mentions its extended variant, the Ortelius projection.) These signs all suggest that the Apian II projection has not been invented until the 19th century.

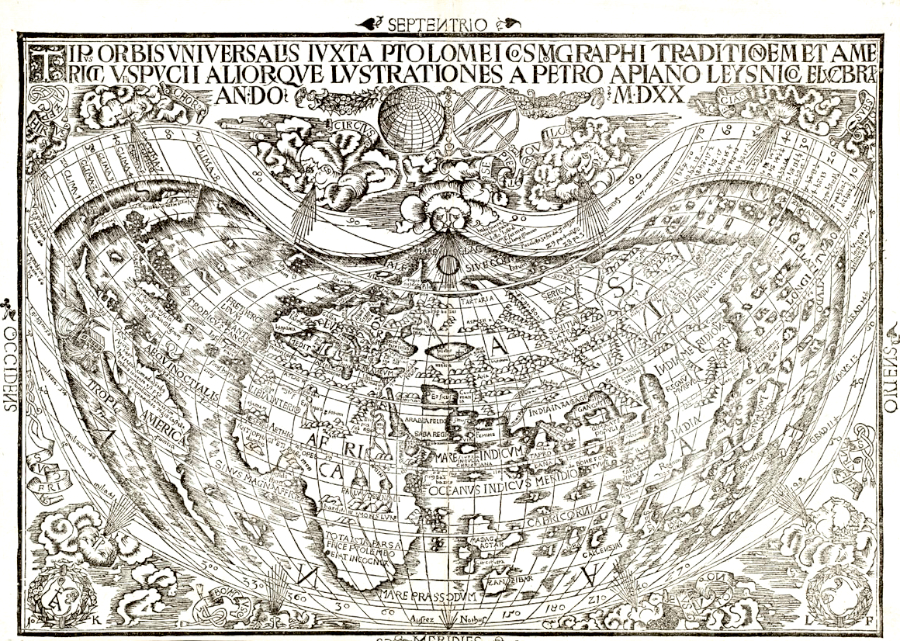

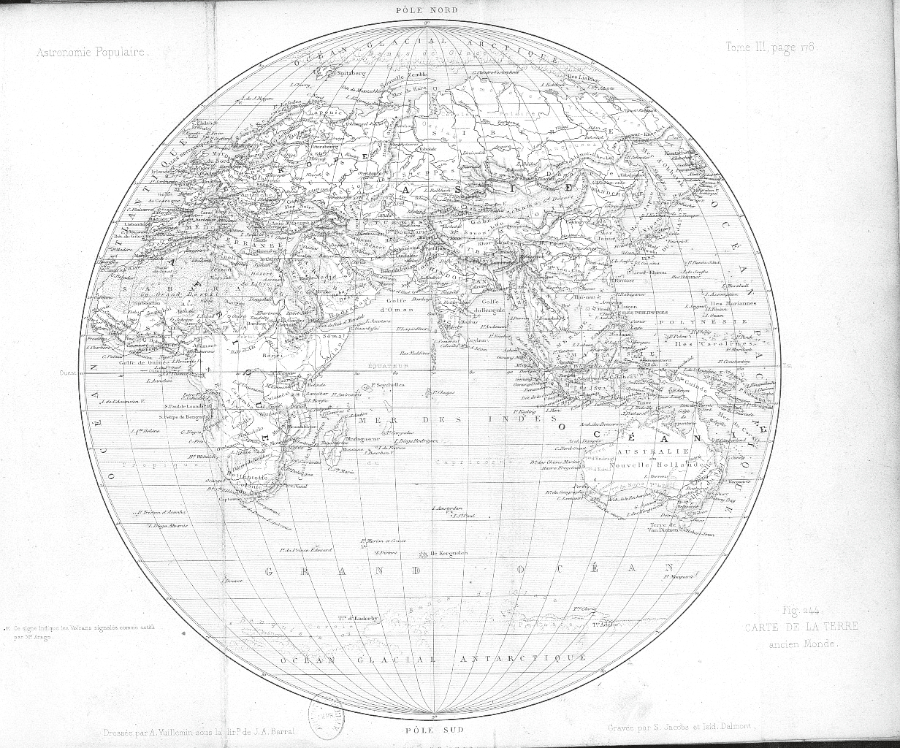

The first confirmed usage of the Apian II projection is found in the book ofFrançois Arago (1856). This map (Fig. 8) shows the volcanic activity of the two hemispheres. Arago does not give any information on his new map projection, but measurements can confirm that this map possesses all properties of the Apian II mapping.

Figure 8: The globular map of Arago (1856) / Slika 8: Globularna karta Aragoa (1856)

What is the source of error?

Dating the origin of a map projection 300 years earlier than its actual development would be a major error, so we must check the original sources of the claim. Reading the first major essay on the history of map projections (d'Avezac, 1863), we do not find any reference to the Apian II projection, only the Apian I projection can be identified under the term 'le systéme d'Apian'.Tissot (1881) also gives a large compendium on map projections. He credits the Apian I projection to Apian, but the Apian II projection is correctly referred to as the projection of Arago.

Hammer translated the book of Tissot to German. Suprisingly, this book (Tissot–Hammer, 1887) credits the Apian II projection to Apian. Hammer admitted that he slightly changed the original text where he found an error. As Hammer does not give a reference for this specific change, we may suggest that it was a result of Hammer's original research. Hammer might have misidentified the rudimentary sketches of the transverse orthographic projection in one of Apian's books as being equivalent of Arago's projection. As we have no more resources on the topic, we can only make assumptions without strong claims. Nevertheless, the author suggests that this is the most probable scenario given the evidences discussed previously.

This error became widespread in the German literature.Maurer (1935) attributes this projection (SNr. 108) to Apian, although Arago is also mentioned.Wagner (1962) describes this map as developed originally by Apian for a hemisphere, but he extends it to the full sphere. This was a base for a handful of Wagner's 'Umbeziffern' projection, also making Arago's map projection well-known, albeit with a bad attribution. The recent large book on the history of map projections (Snyder, 1993) also credits the map projection to Apian referring to his Cosmographica (Apian 1524), but as we saw it earlier, this book contains no traces of the Apian II projection.

Correcting the construction method of Vespucci's map

As demonstrated before, the construction method given byPápay (2021) yields not the first (circular or Vespucci's) but the second (elliptical or Arago's) map projection. We cannot accuse Pápay, because the accessible literature on map projections was biased: The map projections named Apian I and II can be confused easily, and the latter one is probably erroneously dated to the 16th century. Nevertheless, this minor error should be corrected.

The problematic point atPápay (2021) is only his last step: "The shortened parallels are divided equally, in this case into 18 parts. The meridians are curved according to the division." This is an affine transformation of the bounding meridian that results in ellipses, not in circles. We should write instead, for example: "Meridians are drawn as arcs of circles through three points. Two points are determined by the North and South Poles. The third point is based on the divisions of the original square map on the Equator." With this slight modification, we get a possible method how Vespucci might have designed this novel mapping.

Final thoughts

In present paper, we examined the authorship of Apian's map projections. Results imply that neither of these map projections were developed by Apian. Their story is, however, quite different. The Apian I projection was attributed to Apian on the basis of some rudimentary sketches found in his books. Even if one considers them as an intentionally drawn map projection, recent studies discovered an earlier map constructed by Vespucci. The Apian II projection was probably attributed to Apian as a mistake by Hammer, as it very similar to the transverse orthographic projection. Its real developer is likely Arago of the 19th century.

The problem is that now we should change the name of these map projections to Vespucci and Arago projections. However, as science progresses, the origin of other mappings may be questioned. This means that it is unpredictable, which map projections are not named after their real developer. We have already discussed a few other examples in the introduction. At least, the projections mentioned in the introduction have some relation to their eponyms, as Bonne really created maps in the Bonne projection. In spite, Apian had surely never been aware of the Apian II projection, and his contribution regarding the Apian I projection is also questionable.

These arguments suggest that it was not fortuitous to name map projections after their inventor. Of course, these short names are more comfortable in everyday speech, so they will likely remain in use. When teaching map projections, however, we should always mention to the students that the name of the map projection is not necessarily the name of the original inventor.

Problemi u nomenklaturi kartografskih projekcija

Za identifikaciju kartografskih projekcija obično se preferiraju kratki nazivi. Tko bi volio pisati tako nespretne nazive poput 'pseudokona ekvivalentna projekcija s ekvidistantnim paralelama' umjesto 'Bonneove projekcije' ili 'ravnopolarna pseudocilindična ekvivalentna projekcija sa sinusoidnim meridijanima' umjesto jednostavno 'Eckert VI' ili 'Kavrayskiy VI' (Lee, 1944). Čak i zadnji primjer pokazuje da bi ti 'opisni' nazivi temeljeni na kartografskoj mreži i distorzijama projekcija bili dvosmisleni, budući da su projekcije Eckert VI i Kavrayskiy VI vrlo slična, ali različita preslikavanja.

Međutim, imenovanje karata po njihovim autorima ima svoje ozbiljne nedostatke. Na primjer, Kavrayskiy nije bio prvi koji je objavio projekciju Kavrayskiy VI (Snyder, 1993), potpuno ista karta nalazi se I u Wagnerovoj disertaciji, I to nekoliko godina ranije. Bonne nije bio izumitelj Bonneove projekcije, budući da se razvijala postupno tijekom ranog novog vijeka na temelju karte Ptolomeja II. Postoje još slučajevi poput sinusne projekcije, koja se također naziva 'ekvivalentna Mercatorova'. Mercator vjerojatno uopće nije povezan s njoim, budući da to preslikavanje nalazimo u Mercatorovom atlasu tek desetljećima nakon njegove smrti, kada je atlas objavio Hondius (Snyder, 1993). Ipak ta kartografska projekcija postojala je u Mercatorovo doba, kao što je nalazimo na karti svijeta koju je 1570. objavio Cossin.

U ovom radu razmotrit ćemo autorstvo dviju globularnih karata nazvanih po Apianu. Njegovo autorstvo na projekciji Apian II nikada nije dovedeno u pitanje koliko je autoru poznato.

Apian i 'njegove' kartografske projekcije

U kartografskoj zajednici uvriježeno je mišljenje da je njemački kartograf Peter Bienewitz, poznat kao Petrus Apianus ili jednostavno kao Apian, autor dviju globularnih kartografskih projekcija (Snyder, 1993.;Wagner, 1962..). Obje projekcije prikazuju hemisferu u krugu, a paralele su horizontalne ravne linije koje dijele središnji meridijan proporcionalno njihovoj geografskoj širini. Meridijani dijele ekvator proporcionalno njihovoj dužini. Međutim, meridijani su lukovi kružnica u projekciji Apian I, dok su u projekciji Apian II preslikani u poluelipse (sl. 1).

Za obje kartografske projekcije može se dovesti u pitanje autorstvo Apijana. Projekcija Apian I pojavljuje se na kartama nacrtanim kad je Apian bio vrlo mlad. U projekciji Apian II prije 19. stoljeća nisu poznate karte, a sumnjiva je i ova 300 godina duga šutnja. Zapravo, Apian je izradio kartu svijeta, ali ne globularnu, već pseudokonusnu. Njegova karta iz 1520. (koja se obično prilaže njegovim kasnijim knjigama) prikazuje Zemlju u projekciji koja se može vidjeti kao prijelaz između Ptolomejeve II i Bonneove projekcije, vrlo slično karti Waldseemüllera (sl. 2).

Usporedba sličnih preslikavanja

Neke kartografske projekcije površnom gledatelju izgledaju identične. Za razlikovanje ovih kartografskih projekcija potrebno je malo prakse i znanja o tome gdje tražiti manje razlike. To je upravo slučaj za dvije Apianove projekcije. Na primjer, sve paralele imaju konstantno mjerilo u projekciji Apian II, ali meridijani ne dijele paralele projekcije Apian I ravnomjerno (osim ekvatora): gusti su blizu središnjeg meridijana, a rijetki daleko od njega. To je vidljivo uglavnom na većim geografskim širinama. U projekciji Apian I, bimeridijani čine oštar kut sa središnjim meridijanom na polu, ali oni su glatke krivulje okomite na središnji meridijan u projekciji Apian II.

Prije nego što nastavimo, moramo ispitati treću, vrlo sličnu kartografsku projekciju: ortografsku. Budući da se radi o azimutnoj projekciji, ne može se čak ni uzeti u obzir kada se otkriju ravne paralele. Međutim, u poprečnom pogledu, ortografska projekcija rezultira ravnim paralelama, a meridijane preslikava u poluelipse, pa izgleda kao pseudocilindrična projekcija. Nadalje, prikazuje hemisferu u krugu, tako da se također može činiti da je to globularna karta. Kako bismo spriječili pogrešnu identifikaciju, moramo uočiti da u poprečnoj ortografskoj projekciji središnji meridijan nije ekvidistantan: paralele su guste daleko od ekvatora. Za razliku od projekcije Apian II, njeni meridijani nisu ravnomjerno raspoređeni, rijetki su u blizini središnjeg meridijana, a gusti u blizini ruba. Usporedba tih kartografskih projekcija sažeta je utablici 1 i naslici 3.

Podrijetlo projekcije Apian I

Prva poznata pojava kartografske projekcije Apian I datira iz 1505. godine (sl. 4). Pronađena je u Sveučilišnoj knjižnici u Rostocku.Pápay (2021) ispitao je povijest i pozadinu te karte i zaključio da je autor karte vjerojatno Amerigo Vespucci, eponim Amerike. Pápay također tvrdi da je tu kartu izradio Vespucci mnogo ranije, jer nju i njezin sadržaj spominje u pismu napisanom 1500. godine. U to je vrijeme Apian imao samo pet godina, pa možemo sa sigurnošću zaključiti da je vrlo malo vjerojatno da je Apian bio autor.

Studije koje tvrde da je Apijanovo autorstvo obično se pozivaju na njegovu knjigu (Apian, 1524). U toj knjizi nalazimo klasičnu renesansnu kozmografiju temeljenu na Ptolemejevom djelu. U njemu se ne spominje nikakva nova kartografska projekcija. Postoji samo jedna sićušna ilustracija koja prikazuje globus, čiji sustav kartografske mreže pokazuje malu sličnost s projekcijom Apian I (sl. 5.). Međutim, ta skica je rudimentarna, smatrajući je "kartografskom projekcijom" čini se pomalo proizvoljnim. Također treba napomenuti da sve druge ilustracije globusa u toj knjizi koriste zakrivljene paralele, pa je moguće da je ta podudarnost slučajna.

Ipak, na slikama je jasno vidljivo da su meridijani i na Vespuccijevoj karti i na Apianovoj skici ispisani kao lukovi kružnica. Čak se i gore spomenuti uzorak gustih meridijana u blizini središnjeg meridijana i rijetkih meridijana daleko od njega može jasno izmjeriti. To je u suprotnosti s izjavamaPápay (2021) , koji tvrdi da su meridijani Vespuccijeve karte elipse s jednakim razmakom. Pápay pokušava rekonstruirati mogući način izrade Vespuccijeve karte. Međutim, metoda konstrukcije koju on opisuje rezultirala bi projekcijom Apian II (kao što je objašnjeno u sljedećem odjeljku), dok karta radije pokazuje svojstva projekcije Apian I.

Dakle, prema našim najboljim saznanjima, izumitelj kartografske projekcije Apian I je Amerigo Vespucci, a izumio ju je oko 1500. Godine. Apian je možda čuo za tu kartografsku projekciju, budući da vidimo rudimentarnu skicu globusa sličnu toj projekciji. Međutim, ti dokazi su slabi, pa je još uvijek moguće da je Apian nenamjerno koristio kartografsku projekciju nazvanu po njemu.

Podrijetlo projekcije Apian II

Poprečna ortografska projekcija bila je poznata u vrijeme Apijana. On čak prikazuje ilustraciju preko cijele stranice u svojoj knjizi. Međutim, ne nalazimo spomena projekcije Apijana II niti u Cosmographica (Apian, 1524) niti u njegovim drugim knjigama.

Početkom 16. stoljeća kartografi su obično međusobno kopirali karte, a samo su povremeno konstruirali nove kartografske projekcije. Stoga, ako je projekciju Apian II izumio Apian ili netko od njegovih suvremenika, tada bi bilo vrlo malo vjerojatno da ne bismo pronašli nikakvu kartu izrađenu u toj projekciji. Doista nalazimo pregršt karata koje koriste projekciju Apian I. Primjeri uključuju Tramezzinovu kartu iz 1554. Međutim, nije poznata karta u projekciji Apijana II.

Nalazimo neke ovalne karte svijeta stvorene u to vrijeme. Ipak, one nisu u projekciji Apian II: meridijani nisu baš poluelipse, već proizvoljne ovalne linije. Meridijani također nisu ravnomjerno raspoređeni na tim ovalnim kartama. Može se pretpostaviti da je ta razlika tiskarska pogreška. Zapravo, središnji meridijan Vespuccijeve karte (sl. 4) također nije savršeno ekvidistantan, neka manja odstupanja se ipak događaju. Nije li, na primjer, Bordoneova karta (sl. 6) trebala biti u projekciji koju poznajemo kao projekcija Apian II?

U ranom novom vijeku, mreže mjernih grafikona konstruirane su pomoću ravnala i šestara. Projekcija Apian II može se konstruirati vrlo jednostavno. Slijedimo rekonstrukcijuPápaya (2021), u kojoj prikaz hemisfere u projekciji Plate Carrée naziva kvadratnom kartom. Nacrtajte takvu kvadratnu kartu, zatim nacrtajte krug sa središtem na sjecištu ekvatora i središnjeg meridijana kroz dva pola (to će biti meridijani ±90° od središnjeg meridijana). Od izvorne kvadratne karte zadržali smo samo paralele i središnji meridijan. Podijelite sve paralele kvadratne karte na jednaku udaljenost između središnjeg meridijana i oboda kruga (možete nastaviti ucrtavati te udaljenosti izvan kruga ako je potrebna karta svijeta). Nacrtajte meridijane spajajući točke označene na paralelama.

Rezultat navedenog procesa ne daje savršene elipse za sve meridijane, samo nešto vrlo blizu toga. Međutim, bimeridijan ±90° od središnjeg meridijana trebao bi biti savršeni krug, tako da to možemo provjeriti kako bismo procijenili mogu li se rane ovalne karte smatrati primjerima projekcije Apian II. Naslici 6vidimo da niti jedan meridijan nema kružni oblik.Slika 7 je prikazana za usporedbu. Lako je uočiti da se puno bolja točnost mogla postići čak i u 16. stoljeću da se mislio na kružni bimeridijan (ta je karta u Orteliusovoj projekciji, produžetku Apianove I projekcije).

U narednim stoljećima ovalne karte svijeta postale su 'zastarjele', možda ćemo pronaći samo nekoliko primjera Orteliusove projekcije, dajući prednost 'pomodnoj' Mercatorovoj projekciji. Karte hemisfera nacrtane su u poprečnim azimutnim ili Nicolosijevim projekcijama, ne nalazimo kandidate za razvoj karte Apian II. Ne postoje poznate slične karte iz tog doba, s iznimkom Mollweideove karte izumljene 1805. Očigledno,Mollweide (1805) nije bio svjestan vrlo sličnoj projekciji Apian II, jer je ne spominje u svom radu.Fournier (1643) također je razvio pregršt globularnih karata. Iako koristi eliptične meridijane, ne navodi projekciju Apian II, što je sumnjivo, jer se projekcija Apian I spominje kao temeljno djelo. (U stvari, Fournier spominje njezinu proširenu varijantu, Orteliusovu projekciju.) Svi ti znakovi sugeriraju da projekcija Apian II nije izumljena sve do 19. stoljeća.

Prva potvrđena uporaba projekcije Apian II nalazi se u knjiziFrançoisa Aragoa (1856). Ta karta (slika 8) prikazuje vulkansku aktivnost dviju hemisfera. Arago ne daje nikakve informacije o svojoj novoj projekciji karte, ali mjerenja mogu potvrditi da ta karta posjeduje sva svojstva projekcije Apian II.

Što je izvor pogreške?

Datiranje nastanka kartografske projekcije 300 godina ranije od njenog stvarnog razvoja bila bi velika pogreška, stoga moramo provjeriti izvorne izvore tvrdnje. Čitajući prvi veliki esej o povijesti kartografskih projekcija (d'Avezac, 1863), ne nalazimo nikakvu referencu na projekciju Apian II, samo se projekcija Apian I može identificirati pod izrazom 'le systéme d'Apian'.Tissot (1881) također daje veliki kompendij o kartografskim projekcijama. On projekciju Apian I pripisuje Apianu, ali projekcija Apian II ispravno naziva Aragoovom projekcijom.

Hammer je preveo Tissotovu knjigu na njemački. Iznenađujuće, ta knjiga (Tissot–Hammer, 1887) Apianovu projekciju pripisuje Apian II. Hammer je priznao da je malo promijenio izvorni tekst u kojem je našao grešku. Kako Hammer ne daje referencu za ovu konkretnu promjenu, možemo sugerirati da je to rezultat Hammerovog izvornog istraživanja. Hammer je možda pogrešno identificirao rudimentarne skice poprečne ortografske projekcije u jednoj od Apianovih knjiga kao ekvivalent Aragoovoj projekciji. Budući da nemamo više izvora o toj temi, možemo samo iznositi pretpostavke bez jakih tvrdnji. Unatoč tome, autor sugerira da je ovo najvjerojatniji scenarij s obzirom na dokaze o kojima je prethodno bilo riječi.

Ta je pogreška postala raširena u njemačkoj literaturi.Maurer (1935) pripisuje tu projekciju (SNr. 108) Apianu, iako se spominje i Arago.Wagner (1962) opisuje tu kartu koju je izvorno razvio Apian za hemisferu, ali ju je proširio na punu sferu. To je bila osnova za pregršt Wagnerovih 'Umbeziffern' projekcija, čime je Aragoova kartografska projekcija također postala poznata, iako s lošom atribucijom. Nedavna velika knjiga o povijesti kartografskih projekcija (Snyder, 1993) također pripisuje kartografsku projekciju Apianu pozivajući se na njegovu Cosmographicu (Apian 1524), ali kao što smo vidjeli ranije, ta knjiga ne sadrži tragove Apianove projekcije II.

Ispravljanje metode izrade Vespuccijeve karte

Kao što je prije pokazano, metoda konstrukcije koju je daoPápay (2021) ne daje prvu (kružnu ili Vespuccijevu), već drugu (eliptičnu ili Aragoovu) projekciju karte. Ne možemo optužiti Pápaya jer je dostupna literatura o kartografskim projekcijama bila pristrana: kartografske projekcije nazvane Apian I i II mogu se lako pobrkati, a potonja je vjerojatno pogrešno datirana u 16. stoljeće. Ipak, ovu manju grešku treba ispraviti.

Problematična točka kodPápaya (2021) samo je njegov posljednji korak: „Skraćene paralele podijeljene su na jednake dijelove, u ovom slučaju na 18 dijelova. Meridijani su zakrivljeni prema podjeli." To je afina transformacija graničnog meridijana koja rezultira elipsama, a ne krugovima. Umjesto toga, trebali bismo napisati, na primjer: „Meridijani su nacrtani kao lukovi kružnica kroz tri točke. Dvije točke određene su Sjevernim i Južnim polom. Treća točka temelji se na podjelama izvorne kvadratne karte na ekvatoru." S ovom malom preinakom dobivamo moguću metodu kako je Vespucci mogao dizajnirati ovo novo preslikavanje.

Završne misli

U ovom radu ispitali smo autorstvo Apianovih kartografskih projekcija. Rezultati upućuju na to da nijednu od tih kartografskih projekcija nije izradio Apian. Njihova priča je, međutim, sasvim drugačija. Projekcija Apian I pripisana je Apianu na temelju nekih rudimentarnih skica pronađenih u njegovim knjigama. Čak i ako ih netko smatra namjerno nacrtanom kartografskom projekcijom, nedavne studije otkrile su raniju kartu koju je izradio Vespucci. Hammerova projekcija Apian II vjerojatno je pripisana Apianu kao pogreška, jer je vrlo slična poprečnoj ortografskoj projekciji. Njegov pravi tvorac je vjerojatno Arago iz 19. stoljeća.

Problem je u tome što bismo sada trebali promijeniti imena tih kartografskih projekcija u Vespuccijevu i Aragoovu projekciju. Međutim, kako znanost napreduje, podrijetlo drugih mapiranja moglo bi se dovesti u pitanje. To znači da je nepredvidljivo koje kartografske projekcije nisu nazvane po svom stvarnom tvorcu. U uvodu smo već raspravljali o nekoliko drugih primjera. Barem, projekcije spomenute u uvodu imaju neke veze sa svojim eponimima, budući da je Bonne stvarno izradio karte u Bonneovoj projekciji. Unatoč tome, Apian sigurno nikada nije bio svjestan projekcije Apian II, a upitan je i njegov doprinos u pogledu projekcije Apian I.

Ovi argumenti sugeriraju da nisu slučajno nazvane po njihovu izumitelju. Naravno, ti su kratki nazivi ugodniji u svakodnevnom govoru, pa će vjerojatno ostati u upotrebi. Kada podučavamo kartografske projekcije, međutim, uvijek trebamo napomenuti studentima da ime kartografske projekcije nije nužno ime izvornog izumitelja.