Introduction

Many people regularly watch horror films. While it seems clear that sporadically watching horror films will not make us bad people, if it is the main type of media that we consume, then are we still safe? I will defend most horror films from Di Muzio (2006), who worries that we are harming our moral character by watching them. Most horror films (e.g., Candyman (1992, 2021), Get Out (2017), and Scream (1996)) fall into what I call the summit of safe horror (SoSH), the inverse of the uncanny valley effect, wherein almost-but-not-quite-human robots elicit discomfort from viewers rather than empathy. In the SoSH, violence elicits excitement rather than pity for the victims because the violence is mitigated by, among other things, comic relief and foolish choices by the characters. These narrative features allow most horror films to be intense enough to cause excitement and terror yet not so intense as to cause a negative moral attitude to form in our soul, because we feel what Aristotle would consider the appropriate amount of fear. Torture porn (e.g., the Saw sequels) falls outside of the SoSH because it lacks these narrative features, making the violence depicted too intense to be entertaining.

In section 1, I will define “horror film”, contesting Carroll’s definition that requires a monster. In section 2, I will present Gianluca Di Muzio’s critique of horror films. Among other things, he claims that horror films desensitize us to actual violence. In section 3, I will present my rebuttal: only a select few horror films are even capable of negatively affecting our moral character, and they are not guaranteed to have this result. In section 4, I will introduce the uncanny valley effect in robotics and its inverse, the SoSH. In section 5, I will show that most horror films contain narrative features that mitigate the violence. Torture porn, a subset of horror films lacking plot and focusing solely on gore, lies outside the SoSH, and, therefore, enjoying that violence could be problematic. In section 6, I will argue that repeatedly viewing films in the SoSH is safe to do without harming our moral character. Following Aristotle, emotions are not problematic, but feeling excesses or deficiencies of emotions is. The comic relief and illogical character actions prevent us from feeling an excess or deficiency of fear. The films outside the SoSH will not necessarily cause an inappropriate amount of fear but are simply the only ones that could possibly do so. Caution: spoilers ahead!

1. What qualifies a film to be horror?

I am using “horror films” to refer to a great deal of films. There are often distinctions made between thrillers, psychological thrillers, horror films, body horror, slasher films, found footage films, and more. I’m wary of such fine-grained distinctions because films often fall into more than one sub-category. Neil Martin concludes the same thing when he discusses the fuzzy boundaries between psychological thrillers and horror films (Martin 2019, 2). Moreover, he points out that these classifications are post hoc and I agree (Martin 2019, 4).

One classification of horror I disagree with is Noël Carroll’s. Carroll’s goal in The Philosophy of Horror (1990) is to examine art-horror, a distinct genre of media beginning around the time of the publishing of Frankenstein (1818). Films, books, plays, comics, magazines, and any other medium depicting horror imagery is art-horror. By contrast, war, Nazi atrocities, and what we are doing to our planet is natural horror (Carroll 1990, 12-13). This distinction is useful. However, Carroll claims that art-horror must include a monster, “a being in violation of the natural order, where the perimeter of the natural order is determined by contemporary science” (Carroll 1990, 40). Carroll admits that this excludes Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). However, it excludes far more. If Norman Bates is not a monster, then neither are Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Pamela Voorhees from Friday the 13th (1980), Hannibal Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs (1991), or Ghostface from Scream (1996), to name a few. None of these characters are supernatural. Leatherface is merely physically imposing, Pamela Voorhees is driven mad by grief, Hannibal Lecter is highly intelligent, and Ghostface is simply a crafty duo. However, each of their respective films are horror films.

Some might argue that Silence of the Lambs is not a horror film. Martin considers it and films like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Misery (1990), and Black Swan (2010) to be horror films as well (Martin 2019, 2-3). It isn’t just that they contain horror elements, but those elements are the primary focus. Martin contrasts this with films where horror elements are incidental, e.g., the ear-cutting scene in Reservoir Dogs (1992) (Martin 2019, 2). Others agree, calling Silence of the Lambs a paradigm example of modern horror because slasher films have psychopathic serial killers in place of monsters (Gaut 2002, 296).1 While I agree with Berys Gaut, horror films do not need an on-screen, corporeal being as the antagonist because sometimes characters are fighting nature or something unseen.

I want “horror films” to align with common usage and capture as many films as possible. My positive view is that any film where (i) the supernatural, suspenseful, or violent scenarios are repeatedly inciting a fearful response in viewers as a central part of the plot of the film and (ii) the plot does not closely model a real-life scenario is a horror film. Many films have horror elements. However, the first half of the definition excludes children’s films where there is a frightful antagonist, and the second half excludes dramatizations of war and true crime documentaries.

The first conjunct of my definition echos Martin in that it requires the horror elements to be central to the plot. Horror elements include not only supernatural scenarios involving things like ghosts and demons, but also tension and violence caused by human beings. Urban Legend (1998) seems supernatural, but it is revealed to be a quest for revenge by a young woman whose boyfriend was killed. Unlike Carroll, I do not think that we need a monster. In fact, we need never see the antagonist. The Blair Witch Project (1999) is a horror film even though we never see the alleged Blair Witch. The characters are terrorized and scared constantly, making the audience feel fearful. Much the same is true of the Paranormal Activity (2007-2021) series. While many horror films have bleak endings, there can even be horror films with happy endings. Consider The Conjuring (2013-2021) series, where Ed and Lorraine Warren defeat the witch or demon and save the family. There are still several tense situations causing the audience to worry about who will survive, making the horror elements central to the plot.

The second conjunct rules out violence that would be too intense to be entertaining, e.g., war dramas and true crime documentaries. Films such as Dunkirk (2017) and 1917 (2019) depict death, but it is not to incite the audience to fear the enemy soldiers. Instead, we focus on the bravery and sacrifice of those involved. When I was younger, I was scared of Hannibal Lecter after watching Silence of the Lambs (1991), but not the Germans after watching Schindler’s List (1993). By “true crime documentaries” I mean to capture three things. First, actual true crime documentaries such as the Conversations with a Killer (2019) series. Second, serialized shows such as Forensic Files (1996-2011). Third, biographical crime dramas such as Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019). One can be entertained by Leatherface chasing Sally, because there were no such people. Leatherface, like Hannibal Lecter, is loosely based on corpse defiler Ed Gein, but has been altered drastically. We should not be entertained by Zac Efron (as Ted Bundy) lying to Lily Collins (as Elizabeth) about murdering women because Ted Bundy actually had a girlfriend named Elizabeth from whom he kept the murders a secret. Simulated violence has a different effect on us if we know that it is based on a true story.

My definition is going to include many films that could also be categorized as sci-fi and action, which is an upshot. Thrillers by Tarantino will be included, as will many others. I’m intentionally including a lot of films because I want to end up with as many completely defensible horror films as possible. So, I’m starting with a very inclusive definition.

2. Slashing compassion?

In this section I will present Di Muzio’s (2006) critique of horror films and why he finds them to be morally problematic. Basically, he argues that viewing violent media will desensitize us to real-life violence and make us less compassionate.

Di Muzio begins his article by wondering why the moral status of pornography has been discussed at length, yet the moral status of horror films has not. If pornography is morally problematic, he says, then horror films are too. I disagree. The kind of pornography that is morally problematic is not similar to most horror films. Child pornography is problematic. However, problematic pornography bears no significant similarity to the horror films I will defend.

Specifically, Di Muzio likens Tobe Hooper’s 1974 film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to films about Nazi experiments and child torture. If we are unnerved by the latter, then we should be unnerved by the former and films like it that he calls “slasher” or “gorefest”, where

[T]he narration turns on a series of murders, with special emphasis on the chase or struggle that precedes them, on the victims’ wounds and loss of blood, and on their fear and despair. (Di Muzio 2006, 278)

The fact that the atrocities committed by the Nazis were real or that the victims in horror films are often teenagers or adults, rather than children, makes no difference to Di Muzio. I agree that films accurately depicting what Nazis did or torturing a child could be problematic. However, that has no bearing on the moral status of horror films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Even though Leatherface is loosely based on real-life murderer and corpse defiler Ed Gein, the story is changed so significantly that the analogy between The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and a film about Nazis falls apart.

Di Muzio’s main concern is that people who derive joy from watching horror films lack the compassion necessary to make them moral agents. He believes that horror films show nothing but violence, leaving the audience unable to conceptualize what happened, because

[T]he moment the filmmakers attempt to provide some context for the violence, or begin to introduce a ‘moral of the story’, a slasher film starts losing its grip on the audience’s emotions. (Di Muzio 2006, 290)

I disagree. The films that have the greatest effect on audiences introduce the characters thoroughly so that we care about losing them when they eventually die. A film that opens with the death of someone unknown to the audience is not going to be as effective or popular as one that has character development. Being familiar with the characters is one reason why sequels, remakes, reboots, and cinematic universes have become so popular. Di Muzio condemns even films with character development because the viewer

[M]ust at some point detach herself from the film’s content and intentionally limit the degree to which she is affected by the stimulations of extreme suffering she is being exposed to. (Di Muzio 2006, 287)

I will argue that we need not detach ourselves from films in the summit of safe horror because the violence is mitigated by narrative features that allow us to know that what we are seeing is fabricated. As such, these depictions of violence will not desensitize us to actual violence.

3. Refuting Di Muzio

There have been other responses to Di Muzio that defend horror films. I will briefly discuss Marius Pascale’s (2019) for two reasons. First, he offers responses to Di Muzio that are partially correct and, therefore, do not need to be recreated in my argument. Second, his defense is too permissive, meaning that he finds all horror films defensible.

Pascale focuses on reactive attitudes in his response to Di Muzio. First, he notes that Di Muzio oversimplifies by focusing on our need for sympathy and empathy without considering the “moral and psychological downsides of unmitigated sympathy or empathy” (Pascale 2019, 144). Indeed, we can be too sympathetic and fail to have appropriate boundaries with loved ones who seek to take advantage of us. Therefore, Di Muzio’s worry about becoming less sympathetic misunderstands that we should, as Aristotle says, have an appropriate amount of each emotion. Pascale also argues that Di Muzio “provides no evidence to support a link between slasher consumption and reactive attitude decay” (Pascale 2019, 144). Again, he is correct that a psychological study to back up Di Muzio’s claims would help. However, correlation does not imply causation, and even several studies would not convince me that horror films alone are to blame and not the state of the world in which we live. My only issue with Pascale is that he seems to defend horror films that I will not when he characterizes their consumers as having “morbid aesthetic indulgences” and “macabre fascination[s]” (Pascale 2019, 145). As I will argue, consumers who view horror films so that they receive all the benefits from engaging in such actions while suffering none of the consequences might be harming their moral character.

While Pascale makes some excellent points, his view is too permissive, because torture porn like Hostel (2005) and the Saw sequels would be perfectly fine to view repeatedly. Obviously, I want to be more permissive than Di Muzio, but not to this extent. The difference between Pascale’s view and my own is that I am wary of defending torture porn outright. I will not condemn these films, but neither will I defend them. My argument is as follows:

If a horror film contains narrative features that mitigate the violence, then it falls inside the summit of safe horror.

Most horror films contain narrative features that mitigate the violence.

Most horror films fall inside the summit of safe horror. [1, 2]

If a film falls inside the summit of safe horror, then it is safe to view it repeatedly without harming our moral character.

Most horror films are safe to view repeatedly without harming our moral character. [3, 4]

In the following sections, I defend premises 1, 2, and 4.

4. The uncanny valley of robotics and the summit of safe horror

The uncanny valley effect is the phenomenon wherein almost-but-not-quite-human robots elicit discomfort from viewers rather than empathy. I argue that there is an inverse of the uncanny valley effect where most horror films lie that I call the summit of safe horror (SoSH). We actually enjoy that violence because we know very well that it is fabricated.

Masahiro Mori first proposed the uncanny valley effect in 1970. He discovered that the more lifelike a robot gets the more positive emotions it elicits from us, except for those that are almost-but-not-quite-human. Robots with less than a 75% resemblance to humans received more and more favorable responses from the viewers the more they resembled a human. However, Mori found that robots made to look almost-but-not-quite-human elicited a negative response from viewers. Once they were indistinguishable from humans, the robots received positive responses again. Mori coined the term ‘uncanny valley’ to describe the sharp decline in an otherwise upward trend (Mori, MacDorman, and Kageki 2012, 99).

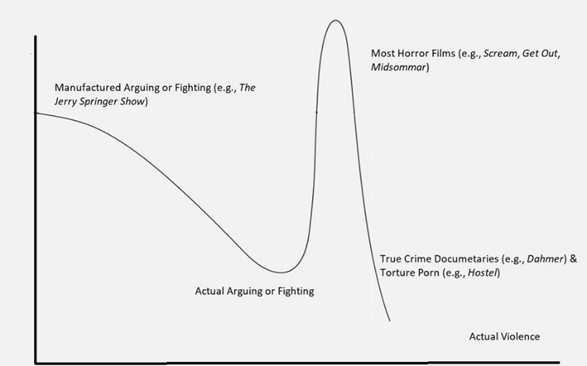

I propose that violence presented on screen elicits a more and more negative response, except in what I call the SoSH, where most horror films exist. See Figure 1. The x-axis represents how intense the on-screen violence is, and the y-axis represents the level of enjoyment that the audience feels upon viewing said media. The violence of films in the SoSH is intense enough to incite the excitement of the audience but not so intense as to incite the pity for the victims that we feel when we watch torture porn. Hence, the surge in enjoyment for media that is violent yet not overly violent, creating the summit.

Figure 1 is just the uncanny valley graph rotated one hundred and eighty degrees with some media examples added. On the far left is manufactured fighting or arguing typical of reality television. Shows like Jerry Springer (1991-2018) and Real Housewives (2006-) are very enjoyable because the violence is very slight, mainly consisting of shouting and tossing drinks in someone else’s face. Actual arguing or fighting shown on the news is less enjoyable. Consider watching police brutality that stops short of resulting in the victim’s death. The sharp incline in enjoyment occurs because we particularly enjoy manufactured violence of the kind found in most horror films. The violence is mitigated by comic relief and illogical character actions, which signals to us that the violence is fabricated. So, it is fun to watch such scenes play out. The steep decline in enjoyment occurs for films outside of the SoSH, for they are too similar to actual violence.

Moreover, the inverse of the uncanny valley effect can be applied to all fiction, not just horror. There are summits of safe action, crime, and science fiction as well. For example, we enjoy watching characters like Mickey and Mallory in Natural Born Killers (1994), Cersei in Game of Thrones (2011-2019), Darth Vader in Star Wars (1977-), and Thanos in Avengers: End Game (2019). This too is perfectly natural and will not harm our moral character.

5. Films in and out of the summit of safe horror

In this section I will defend premise 2: most horror films contain narrative features that mitigate the violence. In 5.1, I will focus on two narrative features that mitigate on-screen violence: comic relief and illogical actions by characters. In 5.2, I will discuss the horror films that fall outside the summit of safe horror (SoSH): torture porn, which are films that lack plot and focus solely on gore.

5.1 Mitigated violence

I will now explain why most horror films fall into the SoSH. The violence is mitigated by narrative features which signal to us that it is fabricated, which is why we feel comfortable viewing it. While there are several such features, I will focus on two: comic relief and foolish actions on the part of the characters that the audience can critique.

Different things can mitigate on-screen violence for different viewers. Sanitizing the violence works for some people. For example, heroes might not bleed on screen, survive fatal wounds, or die off screen. Not seeing the consequences of violence can make it easily digestible for some. As I like gore, I will not dwell on this narrative feature. Instead, I will discuss two features that are present in even the more graphic films.

Comic relief is not only present in comedy films, e.g., Shaun of the Dead (2004) or parodies of horror films, e.g., Scary Movie (2000). Horror films often contain moments of comic relief. Even very heavy films involving child abuse like The Black Phone (2021) have moments of comic relief. A Denver child abductor and killer known as the Grabber has taken Finney Blake. Meanwhile, his younger sister, Gwen, has been having premonitory dreams about the killer. She prays to Jesus for more clues in her dreams so that she can tell the police where to find Finney. After her dreams result in dead ends, Gwen gets down on her knees in front of her makeshift shrine/dollhouse and says “Jesus, what the fuck?” This line received a lot of laughs. The Grabber’s brother is also funny. He has been following the abductions and has deduced that the killer lives nearby his home. The police do not listen because he is overly enthusiastic and has been snorting cocaine. He seems like a conspiracy theorist until it is revealed that Finney is locked in his basement.

Another example of a horror film with comic relief is Get Out (2017). Rose and Chris are a young interracial couple. Rose lures Chris to her parents’ secluded home in upstate New York in order for them to suppress his consciousness and sell his body to the highest white bidder. Chris is generally nervous, adding to the audience’s tension. However, Chris’s friend Rod is a sassy TSA agent who is funny in all his scenes. He tells Chris and Rose jokes on their way to her parents’ house, urges the uncaring police to investigate the missing Black men, and he arrives at the end to save Chris. His scene at the police station is particularly funny. The detective does not believe his story about Rose’s family kidnapping, brainwashing, and turning young Black men into sex slaves. She even invites two coworkers to come listen to the allegedly ridiculous story and the three share a laugh. The audience laughs because such a scheme would be difficult to pull off. On the other hand, I can definitely see old white men bidding for which young Black body they would like to inhabit.

Comic relief is not new. Shakespeare employed comic relief in his tragedies in order to avoid overwhelming the audience. Humans have a complex range of emotions that we need to explore and indeed enjoy exploring. However, in order to make it through a sad movie, we need some moments of levity peppered throughout. The same is true of violent media. Comic relief gives us a break from all the death, but it is also good storytelling. A non-stop bloodbath is not as entertaining as a film where the characters have comic, sad, and romantic moments. We learn about the characters in these breaks and begin to empathize with them and root for their survival, which makes losing them more difficult and their victories more meaningful.

In addition to comic relief, illogical character actions also mitigate the on-screen violence. Characters in horror films also do counterintuitive things all the time, especially when people around them are dying at an alarming rate. The Candyman and Evil Dead series are great examples of films where characters foolishly tempt fate. Candyman is summoned by saying his name five times in the mirror. In the original installment, Helen, being fond of urban legends, jokingly summons him. Candyman frames her for murder, and she is committed. Helen again summons him in a feeble attempt to prove her innocence, unsurprisingly causing more deaths, including her own. Much the same happens with characters in the Evil Dead series reading the Necronomicon. This book, written in blood and bound in human flesh, is always uncovered from a hidden place. Obviously, the book is dangerous. However, in each film, someone reads aloud from the book, which causes numerous possessions and deaths. While we do not expect that reading a book aloud will summon evil, we know that some things should be left alone. If I found a ring in a cemetery, I would not put it on my finger. Likewise, if people around me were dying, then I would not attempt to summon Candyman, even to demonstrate my alleged courage.

Also consider my favorite horror film franchise: Scream. In the original installment, Sidney Prescott receives a phone call from the killer who claims to be on her front porch. She calls his bluff by actually opening her front door and going outside. Later, when the town issues a curfew, the high school students decide to throw a party at Stu Macher’s house. This is not mere teenage bravado. Instead, this stupidity is to advance the plot. We need the characters to be in one central location for the denouement to occur and Stu, being one of the killers, knows this. However, everyone except Billy and Stu should be afraid of Ghostface. I know that they are young, but this is reckless, even for teenagers.

The audience can be critical of characters in horror films because our world is not the same as theirs. As Pete Falconer argues, “a reasonably informed audience will have knowledge and expectations of a fictitious world that the characters inhabiting that world cannot access” (Falconer 2023, 2). They do not (usually) know that they are in a horror film. So, it is no surprise that they act foolishly. Falconer (2023, 3) would not agree with me calling them foolish, because their situations are so implausible that they do not seem to be real possibilities. However, it is not only from the audience’s privileged perspective that Sidney is being foolish, but from an in-universe one as well. This foolishness overrides our empathy and allows the audience to separate ourselves from the characters in the film. Since we would never act this way, we can criticize the characters, which is just like criticizing people on game shows or reality television for making mistakes. We might very well make the same mistake if stressed, but it is easy to shout at the television from the comfort of our living rooms.

Because the violence inside the SoSH is mitigated by various narrative features, the audience enjoys watching Ghostface kill everyone. Likewise, we enjoy watching Norman Bates of Psycho (1960), Leatherface of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Damien Thorn of The Omen (1976), Carrie White of Carrie (1976), Michael Myers of the Halloween (1978-) series, the Xenomorph of the Alien (1979-) series, Jason Vorhees of the Friday the 13th (1980-) series, Freddy Krueger of the A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-) series, Pinhead of the Hellraiser (1986-) series, Pennywise of It (2017, 2019), Hannibal Lecter of The Silence of the Lambs (1991), the titular Candyman, the titular Blair Witch, Samara Morgan of The Ring (2002), Alessa Gillespie of Silent Hill (2006), Sam of Trick ‘r Treat (2007), Harry Warden of My Bloody Valentine (1981), Bughuul of the Sinister (2012, 2015) series, Bathsheba Sherman of The Conjuring (2013), the titular Babadook, Valak of The Conjuring 2 (2016), Art the Clown of the Terrifier (2016-) series, Clown Mask of Haunt (2019), the Grabber of The Black Phone (2021), the titular Pearl, and the titular Abigail kill people. All these films contained violence that was mitigated enough to make them fall into the SoSH, which also includes many more films not mentioned here.

However, not all horror films are created equally. There are films that even hardcore horror fans like me watch only once or simply refuse to watch: torture porn, where the violence is so intense that no narrative features can mitigate it such that it feels fantastical.

5.2 Torture porn

In this section, I will employ Edelstein’s (2006) phrase “torture porn” to refer to graphically violent films that lack comic relief and illogical character actions. I also defend this usage from Lowenstein’s (2011) criticism that such a category does not exist. Torture porn does exist, and it does not fall into the summit of safe horror (SoSH) because such films are too intense to elicit excitement and instead elicit pity for the victims. I am referring to movies like Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1980), Tom Six’s Human Centipede (2009), and Srdjan Spasojevic’s A Serbian Film (2010). As these films are quite graphic, I do not want to discuss their content here. Instead, I will focus on a more palatable franchise that still falls outside of the SoSH: the Saw series.

The Saw sequels are particularly guilty of sacrificing narrative for more and more gruesome deaths. Saw (2004) presents Jigsaw’s kills very briefly, as we spend most of the film with Dr. Gordon and Adam in the bathroom. At the end, there is a shocking reveal that Jigsaw has been in the room with them the entire time, posing as a corpse. Nothing this clever happens in the sequels. They are merely vehicles for increasingly violent deaths. In Saw, Paul Leahy dies of exsanguination because of the barbed wire maze he is placed in. This trap is specially designed for him because he had previously slit his wrist, allegedly for attention. Will he bleed again to save himself or did he really want to die? He must make a choice. The deaths in the sequels lack this poetic justice. In Saw IV (2007), Detective Eric Matthews has his head crushed by two blocks of ice, which has nothing to do with his crimes as a corrupt police officer.

Not only do the traps become more gruesome in the sequels, but it is hard to believe that anyone is supposed to survive any of these traps as they did in the original installment. In Saw, Amanda must retrieve a key from inside a live victim’s stomach in order to unlock the reverse bear trap from her head. The other victim is anesthetized, which makes her job uncomfortable yet manageable. She succeeds and later returns in many of the sequels as one of Jigsaw’s proteges. In Saw 3D (2010) two men and a woman, who has secretly been dating both of the men, are in a trap that is on display to the public. The two men must push saws towards each other or else the woman will be sawed in half. Unlike the original, there is no suspense as to whether someone will live or die. Instead, it is inevitable that one member of the trio will die. Indeed, the men, upset by her deception, agree to let the woman die.

Films like the Saw sequels fall under the category known as “torture porn”, a phrase coined by David Edelstein. It is distinct from other sub-genres of horror, e.g., horror comedy or body horror, because the focus is on excessive gore. Edelstein focuses on Hostel (2005), The Devil’s Rejects (2005), Saw (2004), Wolf Creek (2005), and The Passion of The Christ (2004). It isn’t just that the gore is ramped up for Edelstein, but that the characters are too realistic:

Unlike the old seventies and eighties hack-’em-ups (or their jokey remakes, like Scream), in which masked maniacs punished nubile teens for promiscuity (the spurt of blood was equivalent to the money shot in porn), the victims here are neither interchangeable nor expendable. They range from decent people with recognizable human emotions to, well, Jesus. (Edelstein 2006)

Notice that Scream is silly enough for Edelstein to contrast it with torture porn. Furthermore, he considers the characters in Scream to be expendable. Recall from the previous section that I noted several moments in Scream where we get frustrated with the character’s stupidity. So, Edelstein would agree with me that comic relief and illogical character actions play a big part in making on-screen violence enjoyable.

Lowenstein argues that torture porn does not exist, and that such films are better described as spectacle horror. For Lowenstein, torture porn is “a needlessly brutal and graphically explicit image of mutilation” and spectacle horror is where “this investment in bloody, intense attractions is not gratuitous, but central to the pleasure of watching the film” (Lowenstein 2011, 46-47). He uses the scene in Hostel where Paxton is hiding on a cart of corpses and a severed hand that was blocking the cart’s wheel gets placed by his face. Since this shot is from a point of view impossible for Paxton and the severed hand is not an important plot device, Lowenstein argues that this scene is specifically addressing the audience and how they enjoy this disgusting spectacle (Lowenstein 2011, 47). He objects to using “porn” “as a transparent term for self-evident moral disapproval [that] (…) ignores the possibility of spectacle horror’s mode of feeling history as anything other than immoral and irresponsible” (Lowenstein 2011, 51). Lowenstein makes several comparisons between Hostel and the Iraq War that I completely missed, and I am now convinced that Hostel is a spectacle to reflect the brutality of the war and American privilege.

I agree that the brutality of Hostel is, in part, social commentary. However, unlike Lowenstein, I find that it leans too far into the gore and should be called “torture porn”. Porn is not necessarily morally bad, even the sexual content typically categorized as such. It is a category of media that, like other categories, has morally good, morally bad, and morally neutral content. Torture porn is potentially problematic not because it is porn, but because of the unmitigated violence.

I am using “porn” as Thi Nguyen and Bekka Williams do, referring to something “engaged with for the sake of a gratifying reaction, freed from the usual costs and consequences associated with the represented content” (Nguyen and Williams 2020, 148). While they do not specifically mention torture porn, they differentiate between harmless porn and harmful porn. Food porn, the viewing of images of expensive food, is harmless, while moral outrage porn, the simplification of an opponent’s beliefs to magnify outrage, is harmful (Nguyen and Williams 2020, 149). So, contra Lowenstein, “porn” is a term that just refers to something we experience vicariously. Indeed, Nguyen and Williams mention baking porn, closet porn, headphone porn, and real estate porn. All of these are morally neutral. However, viewing excessive film gore because it offers all the excitement of committing violent acts without the risk of jail time will encourage a bad moral character to form.2

Let’s return to the SoSH and why the Saw sequels and other torture porn falls outside of it, because it is not just about the graphic nature of the violence. There is no comic relief in the Saw franchise and people are murdered for all-too-common reasons, like doing their job as an insurance agent. Because Jigsaw is a main character, we are primed to feel pity for him that his cancer was not irradicated. However, people die of cancer all the time in the real world. Insurance agents simply assess claims and see if conditions are preexisting or not. There are no grounds for Jigsaw’s vengeance against a lot of his victims. The only reason the audience would be on Jigsaw’s side is because we know his backstory. If William Easton, the insurance executive from Saw VI (2009), were a main character whose backstory we saw, then we would not enjoy his death.

A film that supports this claim is Drag Me to Hell (Sam Raimi 2009). The main character, Christine, is a loan officer hoping to get promoted to assistant branch manager. She needs to show that she can be firm. So, she denies a third mortgage extension to an elderly woman, Sylvia. Sylvia curses Christine to be tormented and dragged to hell by the demon known as the Lamia. We follow Christine’s story, as Sylvia dies early on. We are upset when Christine gets dragged to hell in front of her boyfriend at the train station, because she did what many of us would have done if in her shoes. If, however, we were following Sylvia’s story, then we would root for Christine to get what’s coming to her.

Drag Me to Hell falls in the SoSH because there is comic relief, and we are saddened that such an innocent mistake leads Christine to such a gruesome fate. Saw VI is not in the SoSH because the audience is led to feel bad for Jigsaw and not William. Moreover, Drag Me to Hell contains comic relief in the form of graphic scenes of Sylvia’s corpse vomiting into Christine’s mouth. These scenes are so over the top that they are played for laughs, something for which Raimi is famous.

6. Why the summit is safe

Let’s take stock. We often take pleasure in viewing on-screen violence that is mitigated, i.e., violence which includes comic relief and foolish actions by the characters. However, we should not feel the same pleasure in viewing unmitigated violence. I will now explain why this is, and why our moral character is safe while viewing violence mitigated by narrative features. In 6.1 I will argue that, while feeling the Aristotelian mean of an emotion like fear is a good thing, feeling an excess or deficiency is when it begins to harm our character. In 6.2 I will argue that we watch and rewatch horror films not only to experience fear but because of the artistic value of clever storytelling, Easter eggs, and foreshadowing.

6.1 Aristotle and emotions

The idea that watching someone pretend to misbehave will make the audience want to misbehave dates back to Plato (Republic 391e-392a). While Plato might have a point about young, impressionable minds, I am concerned only with adult viewers. It is natural for adult viewers to enjoy mitigated violence like the kind that takes place in horror films inside the SoSH. Moreover, doing so will not negatively affect our moral character because emotions in themselves are not bad. Indeed, the appropriate amount of fear is good, because it keeps us alive.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle tells us that emotions in themselves are not bad, but feeling too much or too little of them is:

I speak of moral character, for this is concerned with emotions and actions, of which there is an excess, a deficiency, and a mean. For example, one can be terrified, courageous, feel desire, anger, and pity, and experience pleasure and pain in general, either too much or too little, and in both cases wrongly. Whereas to feel these feelings at the right time, on the right occasion, towards the right people, for the right purpose and in the right manner, is to feel the best amount of them, which is the mean amount, which is the very thing that is excellence. (NE 1106b16-23)

So, being afraid can happen not enough, too often, or the right amount. Having the appropriate amount of fear and confidence is called courage (NE 1115a6-7). Aristotle has a very specific definition of courage in mind: courage is shown when a man can defend himself nobly from death (NE 1115b3-4), because it is the most dreadful thing (NE 1115a26). So, only soldiers in his time could show courage. However, we now recognize that women and civilians can also be courageous. We can be courageous while fighting cancer, battling depression, or even watching a horror film (see also MacAllister this issue, 320).

I judge how good a horror film is by how nervous I am after I watch it. I don’t like heights or driving fast cars, but I do like being scared by horror films. Following Aristotle, nothing is wrong with being scared so long as it is done in the right way, for the right amount of time, and in response to the right objects. I take it for granted that horror films are an appropriate object of fear and will focus on the appropriate amount and time.

Obviously, running in terror from fabricated on-screen violence is an excess of fear, because we are in no real danger at that time. Furthermore, doing so would cause us to be afraid of every raised voice and unexpected sound such that we would become cowardly. It would also be bad for our moral character for us not to react at all to the on-screen violence, for we could become desensitized to real-life violence. However, an increased heart rate, the desire to shut our eyes, and the feeling that something similar might befall us later is typical. I argue that this is the appropriate amount of fear to feel during a horror film.

Not fearing what we ought to fear is rashness. Aristotle says that excess fearlessness is madness (NE 1115b26). Someone who feared neither earthquakes nor floods would not be courageous, but rash (NE 1115b27-8). Indeed, our mortal flesh is no match for nature’s power. Watching a horror film and then being inspired to go to a cemetery in the secluded woods in the middle of the night is not courageous; it is rash. The supernatural things we see in films will not occur, but we are making ourselves vulnerable to hungry animals or people with bad intentions that would find us alone. Moreover, if no one knows where we are, and there is no one around to find us, then we could get lost or hurt.

Having an appropriate amount of fear keeps us alive. Locking our doors is not cowardly, merely prudential. Wearing our seatbelt is not cowardly, we are merely attempting to avoid unnecessary bodily harm. A jolt in adrenaline from watching a scary movie reminds us that we are only human and can be undone in a multitude of ways. After Final Destination 2 (2003), many drivers avoided being directly behind a log truck on the highway. Again, this is not cowardly, merely precautious. Never driving again would be cowardly. Watching Jaws (1975) should make us wary of swimming for a day or two, but never enjoying the ocean again would be cowardly.

The films outside of the SoSH depict violence so intensely that they might cause some people to feel the wrong amount of fear, either too much or too little. Consider the torture and murder of Josh in Hostel (2005). A Dutch businessman drills holes into his body and eventually slits his throat. Some people might react to such a scene as though they were viewing actual torture and get physically sick or cry. There is no comic relief, and the scene is very realistic. Certain audience members could be overwhelmed and traumatized by this scene. On the other hand, the very realistic nature of the scene might cause some people to become used to such graphic violence such that they would not react appropriately if this were actually taking place in front of them. This is exactly what Di Muzio is worried that all horror films do. However, the films in the SoSH will not do this. They are exciting enough to raise our heart rates, but not so much to overwhelm us.

The excitement of horror films is one reason for their popularity. However, there are other features that inspire repeat watching. In the next section, I will focus on two: foreshadowing and Easter eggs.

6.2 The art of horror

Di Muzio and others might object that if viewers aren’t enjoying the simulated violence of horror films, then there is no reason to watch or rewatch them. However, Freeland (2000) argues that the audience appreciates the art form of filmmaking, not the violence itself. She proposes

[T]hat audiences do not simply relish the sorts of spectacles [she has] just described as a kind of vicarious violence. Rather, fans often look for the way that the numbers employ wit, parody, intertextuality, and cross-references to earlier films. (Freeland 2000, 262-263)

She is absolutely correct in her observation, because I rewatch horror films to search for hidden Easter eggs and foreshadowing all the time.

Alfred Hitchcock’s cameos in his films are infamous. Whether he is walking by the main characters, playing cards on the train (as in Shadow of a Doubt (1943)), or his visage simply appears on a neon sign in the background (as it does in Rope (1948)), looking for him is a good reason to rewatch his films. Several other directors follow in his footsteps and have their own cameos in their filmographies. Sam Raimi’s 1973 Oldsmobile is practically a character in the Evil Dead series, and it also shows up in most of the other movies he directs or produces. James Wan hides Billy, the puppet from the Saw series, in a host of films he directs. Scream’s director, Wes Craven, appears as a janitor in Freddy Krueger’s sweater in the original 1996 installment, which is a nod to his Nightmare on Elm Street series.

Observant fans can also benefit from clever foreshadowing horror films include. In I Still Know What You Did Last Summer (1998), Julie’s friend Karla wins tickets to the Bahamas from a radio show. However, the trivia question she was asked is “What is the capital of Brazil?” and she incorrectly answers “Rio de Janeiro”. So, we know early on that they have been lured to the island by the killer. It is no coincidence that Julie is the target of another attack; this incident is directly related to the last film. In The Witch (2015), twins Mercy and Jonas sing an ominous song about the family’s goat, Black Phillip, that alludes to the ending where he turns out to be the devil. In The Conjuring 2 (2016), Valak’s name is spelled out in the background of multiple scenes, and knowing the demon’s name is its ultimate undoing. The opening of Midsommar (2019) focuses on a tapestry that appears to show the end of winter and the coming of spring. It actually outlines the entire plot of the film, even Christian’s fate inside the bear. Hidden details like this promote repeat viewing, not only the gore of the deaths.

Horror films are art, which contradicts Gaut’s claim that most horror films lack artistic worth (2002, 298). So much creative effort goes into the acting, writing, special effects, cinematography, etc. that should not be ignored. Horror films are so diverse that to assume they are all slashers with no overarching theme or moral lesson is foolish. Dawn of The Dead (1978) ends with Fran and Peter in a helicopter escaping a mall overrun by zombies. Seconds earlier, Peter had contemplated taking his own life. Even if there is no safe place left for them, they do not give up. This is a life lesson that makes the film go from good to great.

Conclusion

I have defended most horror films from the claim that watching them makes us develop a bad moral character. I offered my view that most horror films fall into what I call the summit of safe horror (SoSH), wherein staged violence elicits excitement rather than pity. My view is rooted in the uncanny valley effect in robotics. I left torture porn out of the SoSH because the violence they depict is not mitigated, i.e., there is no comic relief, and no foolish choices are made by the characters. As a result, we might not be able to repeatedly watch their antagonists commit atrocities because the real-world consequences are shown, and it could desensitize us to actual violence. We can, however, watch the antagonists of films in the SoSH be violent because the violence is clearly fictitious. Enjoying films in the SoSH is natural and will not desensitize us to actual violence.

Acknowledgments

I owe my thanks to Ryan Ross, the organizers of the Aesthetic Education and Screen Stories conference at the University of Rijeka, my many students and colleagues who have endured the presentation of these ideas, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous drafts. I especially owe my thanks to my husband, Vince, for always taking me to the movies to “do research”.