INTRODUCTION

Lenvatinib (4-[3-chloro-4-( N’-cyclopropylureid)phenoxyl]-7-methoxyquinoline-6-carboxamide) is an orally effective tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that selectively inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1–3 (VEGFR 1-3) (1–3), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-3 (FGFR 1-3) (1–3), platelet-derived factor receptor (PDGFR) (1) and proto-oncogenes RET and KIT (1, 2). As such, lenvatinib is considered a multiple TKI and has been approved for the treatment of progressive, radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (4) and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (5). In combination with other drugs, lenvatinib is used to treat advanced renal cell (6) and endometrial (7) carcinoma. It has also been tested alone or in combination with other drugs against several other types of cancer, such as gastric (8), pancreatic (9), and breast (10) cancer. Thus, lenvatinib is becoming increasingly used in therapy.

Once administered to patients, lenvatinib is quickly absorbed, excreted, and eliminated in urine and feces (11). An estimated 2.5 % of the administrated parental compound is found in urine and feces, indicating that lenvatinib is highly metabolized before excretion (11). Inoue et al. indicated that various CYPs and aldehyde oxidase are involved in the metabolism of lenvatinib, albeit without specifying the CYP enzymes responsible for this metabolism (12). The slightly increased systemic exposure to lenvatinib following its coadministration with ketoconazole in healthy adults suggested that CYP3A4 is involved in the metabolism of lenvatinib (13).

This role of CYP3A4 was confirmed when screening human cytochromes P450, which showed that CYP3A4 was the most efficient enzyme in the formation of lenvatinib metabolites, namely lenvatinib N-oxide, N-descyclopropyl lenvatinib and O-desmethyl lenvatinib. Its efficiency was even increased in the presence of cytochrome b5 (cyt b5) (14). Similar results are also known for other TKIs (15, 16). The second most important human CYP with respect to lenvatinib metabolism seems to be CYP1A1, followed by CYP1A2. However, only one metabolite ( O-desmethyl lenvatinib) is formed by these enzymes (14). Otherwise, the metabolism and effects of this drug remain unclear. Therefore, further research is needed to better understand the pharmacological properties of lenvatinib. Knowing the fate of the drug in rats may be relevant and helpful as rats tend to be a suitable model organism (17–20).

In view of the above, this study examined the metabolism of lenvatinib by rat CYPs in vitro and evaluated the effect of lenvatinib on the expression and activity of selected CYPs after gastric gavage administration in rats. The in vitro metabolism of lenvatinib in cell-free systems was determined using hepatic subcellular systems (microsomes) isolated from livers of rats treated with inducers of CYPs responsible for drug biotransformation. In addition, enzymes capable of metabolizing this anticancer drug were identified using recombinant CYPs expressed in SupersomesTM.

EXPERIMENTAL

Material and chemicals

Lenvatinib was purchased from MedChemExpress (USA). The standard of lenvatinib N-oxide was from Toronto Research Chemicals (Canada). Methanol was purchased from VWR (USA). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium were purchased from Promega (USA). Sudan I was purchased from BDH (UK), and Precision Plus Protein Western C Standard was purchased from Bio-Rad (USA). 4’-OH-Sudan I and 6-OH-Sudan I were provided by Dr Václav Martínek (Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic). Ammonium acetate, NADPH, ethyl acetate, 7-ethoxyresorufin, 7-methoxyresorufin, phenacetin, 6β-hydrotestosterone, and other chemicals were all purchased from Merck (Germany). The purity of all chemicals met the standards of the American Chemical Society unless noted otherwise. The antibodies were purchased from the following vendors: goat anti-rat CYP1A1 primary antibody from Daiichi Pure Chemicals (Japan), rabbit anti-rat GAPDH primary antibody, anti-chicken IgY- and anti-rabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase secondary antibodies from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), rabbit anti-rat CYP1B1 primary antibody from Boster Biological Technology (USA), rabbit anti-rat CYP2C11 primary antibody from Affinity BioReagents (USA) and goat anti-rat CYP3A primary antibody and anti-goat IgG alkaline phosphatase secondary antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). In turn, chicken anti-rat CYP1A2 was prepared in the laboratory of Professor Hodek (Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) as described previously (21). RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) reagents were purchased from the following vendors: GENEzol Reagent from Geneaid (Taiwan), and High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix and TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for CYP1A2, CYP2B1, CYP2C11, CYP3A1, and β-actin from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). PrimeTime Std® qPCR Assays for CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP2A2, CYP2D1, CYP2E1, and CYP3A2 were purchased from IDT (USA).

Rat recombinant enzymes were used in SupersomesTM from Corning® Gentest™ (USA). In SupersomesTM, microsomal fractions were isolated from insect cells transfected with baculovirus constructs containing cDNA of rat CYP enzymes (CYP1A1/2, 2A1/2, 2B1, 2C6/11/12/13/, 2D1/2, 2E1, 3A1/2). These SupersomesTM also express NADPH:CYP oxidoreductase (POR). However, they are microsomes (particles of the broken endoplasmic reticulum), so other enzymes (proteins) of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (such as NADH:cytochrome b5 reductase and cytochrome b5) are also expressed at basal levels in these SupersomesTM. In addition, we utilized SupersomesTM, which overexpressed cytochrome b5, at a 1:5 CYP-to-cytochrome b5 molar ratio. In SupersomesTM, where cytochrome b5 was not overexpressed (CYP1A and 2D), pure cytochrome b5 was added to reach a CYP-to-cytochrome b5 molar ratio of 1 to 5. SupersomesTM with purified cytochrome b5 were reconstituted as described previously (22, 23).

Animal pretreatment and microsome isolation

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Regulations for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (311/1997, Ministry of Agriculture, Czech Republic) and hence in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Male Wistar rats (∼125−150 g; five weeks old) were placed in cages in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms, acclimatized for five days, and maintained at 22 °C with a 12 h light/dark period. Standard diet and water were provided ad libitum. For specific CYP enzyme induction, rats (10 animals/group) were treated with benzo[ a]pyrene (BaP; mainly CYP1A) (24), Sudan I (mainly CYP1A (25)), phenobarbital (PB; mainly CYP2B) (26), ethanol (mainly CYP2E1) (27) and pregnenolone 16α-carbonitrile (PCN; mainly CYP3A) (28) as follows: i) treated by gastric gavage with a single dose of 150 mg kg–1 body weight (bw) BaP dissolved in sunflower oil (1 mL) as reported (24), ii) injected i.p. with 20 mg kg–1 bw Sudan I in maize oil once a day, for three consecutive days, as reported previously (25), iii) treated with PB (0.1 % in drinking water for 6 days), as reported (29), iv) treated with ethanol (0.1 % in drinking water for 6 days), as described previously (30), v) injected i.p. with 50 mg kg–1 bw PCN dissolved in maize oil (1 mL) once daily for four consecutive days, as reported (31), vi) untreated animals (mainly CYP2C) (32) did not receive any treatment. To examine the impact of lenvatinib, 30 mg kg–1 bw of lenvatinib in 1 % Tween was administered to rats by gastric gavage once, whereas only 1 % Tween was administered to the respective controls (4 animals/group). In all treatment groups, rats were euthanized 24 h after the last treatment by cervical dislocation, livers snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C until further processing. In this study, pooled microsomes prepared according to established protocols were used for all experiments (24). Microsomal fractions were stored at -80 °C until analysis. Protein concentrations in the microsomal fractions were assessed using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard (33).

Lenvatinib oxidation by hepatic microsomes and CYP enzymes

Unless stated otherwise, incubation mixtures used to study lenvatinib metabolism were done in triplicates and contained 100 mmol L–1 potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mmol L–1 NADPH, rat hepatic microsomes (0.25 mg protein), or rat recombinant CYPs in SupersomesTM (25 pmol) and 50 µmol L–1 lenvatinib dissolved in 5 or 2.5 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a final volume of 500 μL for incubations with hepatic microsomes or 250 μL for incubations with recombinant enzymes (Supersomes). The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH. In control incubations, either microsomes, CYP, or NADPH were omitted. Incubations were performed at 37 °C for 20 min in open plastic tubes. Lenvatinib oxidation was linear up to 40 min of incubation. The reaction was stopped by extraction with ethyl acetate (2 × 1 mL). Extracts were evaporated, dissolved in 50 µL methanol, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was used to separate and quantify lenvatinib and its metabolites (Ultimate 3000, Thermo ScientificTM, USA). The following conditions were used for HPLC: Nucleosil® EC 100-5 C18 reverse phase column (150 × 4.6 mm, Macherey Nagel); injection 10 μL, the eluent was 1.25 mmol L–1 ammonium acetate in water (pH 4) with acetonitrile 30:70 with a 0.7 mL min–1 flow rate and detection at 254 nm. The structures of the metabolites were confirmed by mass spectroscopy, and in the case of lenvatinib N-oxide, this was also done using a synthetic standard, as previously described (14).

Western blot analysis

For CYP enzyme detection, 50 µg of microsomal proteins were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10 % acrylamide, Bio-Rad). After the electrotransfer, the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was blocked in a solution of 5 % skim milk in PBS-Triton X100 buffer (0.134 mol L–1 NaCl, 1 mmol L–1 NaH2PO4, 1.8 mmol L–1 Na2HPO4, 0.3 % ( m/V) Triton X-100, pH 7.2) for 1 h at room temperature. Individual CYPs were incubated with the appropriate antibody diluted according to the manufacturer's protocol in 5 % skim milk in PBS-Triton X-100 buffer overnight at 4 °C. After washing 3 times in 5 % skim milk in PBS-Triton X100 buffer, the membrane was incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG (dilution 1:10,000), anti-chicken IgY (dilution 1:1000) or anti-goat IgG (dilution 1:2500) in 5 % skim milk in PBS-Triton X100 buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized with the alkaline phosphatase substrate, a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium solution in ALP buffer (100 mmol L–1 Tris/HCl, 150 mmol L–1 NaCl, 1 mmol L–1 MgCl2, pH 9). To normalize protein concentration and expression, we used glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), because this protein is constitutively expressed in cells, as an invariant internal control in Western blot analysis (dilution of the rabbit primary antibody was 1:5000).

Enzyme activity assay

Enzyme activities of CYP1A1, 1A2, and 3A1/2 were determined in rat hepatic microsomes using the following marker reactions: 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation (EROD) (34) and Sudan I hydroxylation (21, 35) for CYP1A1, 7-methoxyresorufin O-demethylation (MROD) for CYP1A2 (34), 16α-hydroxylation of testosterone for CYP2C11 (36) and 6β-hydroxylation of testosterone for CYP3As (37). All reactions were performed in triplicate in a linear range of product formation with respect to incubation time and the final concentration of organic solvent in the incubation mixture did not exceed 1 %. Control samples did not contain NADPH or microsomes to detect eventual product formation without CYP mediation.

For EROD and MROD, incubation mixtures consisted of 100 mmol L–1 potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2 µmol L–1 7-ethoxyresorufin or 7-methoxyresorufin (stock solution dissolved in DMSO), 0.5 mg mL–1 microsomal protein and NADPH (0.5 mmol L–1) in a final volume 200 μL. The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH after 5 min pre-incubation of a mixture of buffer, substrate, and microsomes at 37 °C. The formation of the reaction product resorufin was continuously measured fluorometrically (excitation 530 nm, emission 585 nm) for 10 min at 37 °C in a microplate using Infinite® M200 Pro (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). The amount of resorufin formed was evaluated using a calibration curve of the variation of fluorescence intensity as a function of known concentrations of the resorufin standard.

For Sudan I hydroxylation, incubation mixtures consisted of 50 mmol L–1 sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 100 µmol L–1 Sudan I (stock solution dissolved in methanol), 0.5 mg mL–1 microsomal protein and 0.5 mmol L–1 NADPH in a final volume 500 μL. The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH after 5 min pre-incubation of a mixture of buffer, substrate, and microsomes at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped after 30min incubation at 37 °C in open tubes by adding 1 mL of ethyl acetate. After the addition of 5 μL of 1 mmol L–1 phenacetin (in methanol) as an internal standard, extraction into ethyl acetate was performed twice and the extract was evaporated to dryness under a vacuum at 37 °C, dissolved in 30 μL of methanol and analyzed by HPLC (Macherey-Nagel column CC250/4 Nucleosil 100-5 C18 HD preceded by a guard column, injection 20 μL, mobile phase methanol/0.1 mol L–1 NH4HCO3 at pH 8.5 and a 9:1 ratio, 0.7 mL min–1 flow rate, 35 °C temperature, and detection at 254 and 480 nm). The elution times of the separated peaks were compared with the elution times of Sudan I, 4´-OH-Sudan I, and 6-OH-Sudan I standards and quantified in relation to phenacetin.

For testosterone hydroxylations, incubation mixtures consisted of 100 mmol L–1 potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 50 µmol L–1 testosterone (stock solution dissolved in methanol), 0.5 mg mL–1 microsomal protein and 50 µL NADPH-regenerating system (1 mmol L–1 NADP+, 10 mmol L–1 MgCl2, 10 mmol L–1 glucose-6-phosphate, 1 U mL–1 glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) in a final volume 500 μL. The reaction was initiated by adding an NADPH-regenerating system after 5 min pre-incubation of a mixture of buffer, substrate, and microsomes at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped after 15min incubation at 37 °C in open tubes by adding 100 μL of 1 mol L–1 Na2CO3/2 mol L–1 NaCl and vortexed thoroughly. After the addition of 5 μL of 1 mmol L–1 phenacetin as an internal standard, extraction into 1 mL ethyl acetate was performed twice, and the extract was evaporated to dryness under vacuum at 37 °C, dissolved in 30 μL of methanol and analyzed by HPLC (Macherey-Nagel column CC250/4 Nucleosil 100-5 C18 HD preceded by a guard column, injection 20 μL, a linear gradient of 0–100 % mobile phase B in mobile phase A for 27 minutes, mobile phase A – 50 % ( V/V) methanol, mobile phase B – 75 % ( V/V) methanol, flow rate 0.6 mL min–1, temperature 35 °C, detection at 254 nm). The testosterone metabolites were identified by co-chromatography with authentic standards. The peak area of 16α- and 6β-OH-testosterone was related to the peak area of the internal standard.

The HPLC assay analyses were done on Agilent Technologies 1200 series (USA).

Relative gene expression analysis in rat livers

Individual liver pieces of rats from one premedication group (control rats and rats exposed to lenvatinib) were pooled and four independent isolations of total RNA were performed. mRNA was quantified by qPCR, as previously described (38) , albeit with minor changes in chemicals (see Material and chemicals). The results and significant differences were analyzed by the REST 2009 software (Qiagen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

For statistical data analysis, we used Student’s t-test. All p-values were two-tailed and considered significant at a probability level of 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Oxidation of lenvatinib by hepatic microsomes in vitro

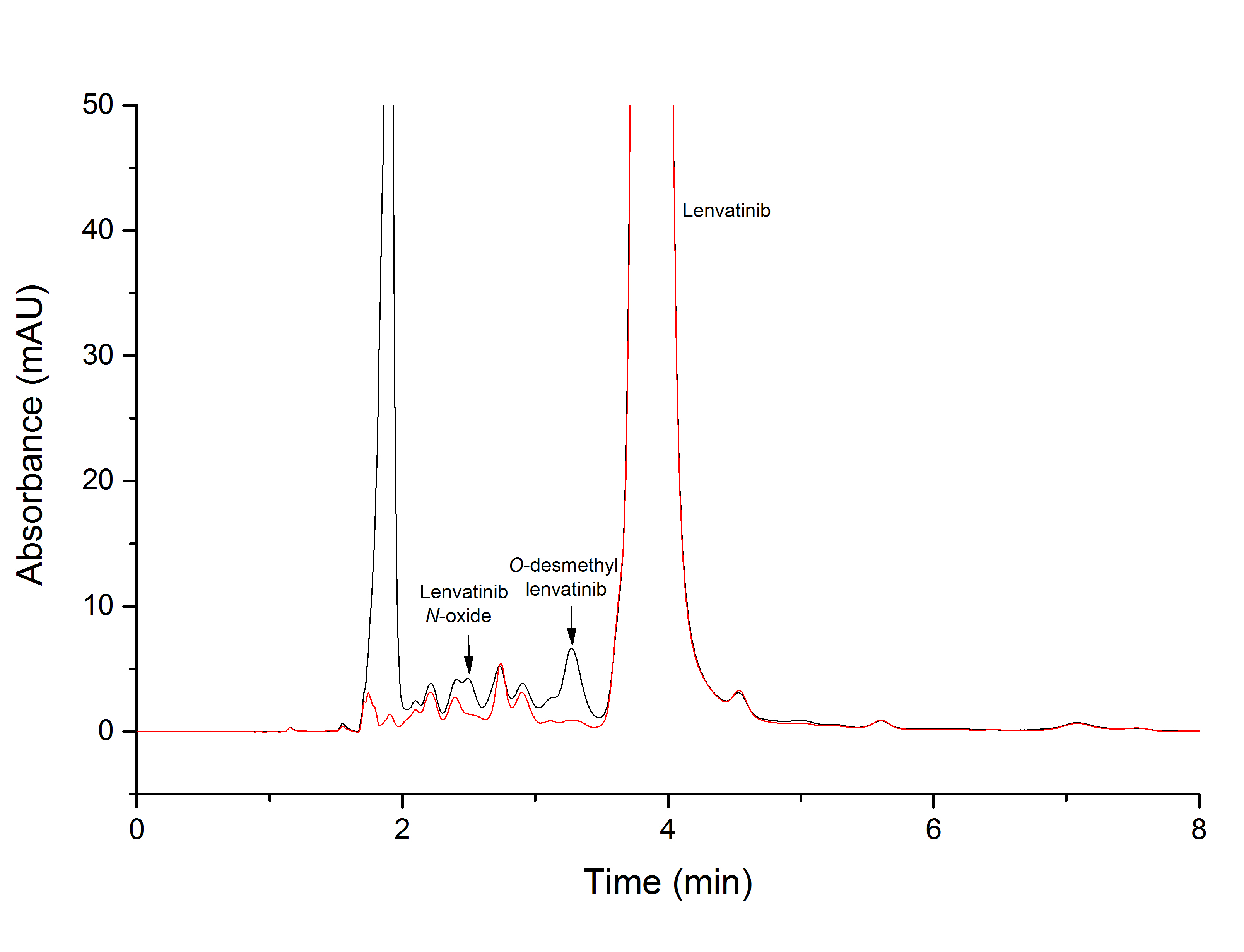

First, we investigated the ability of the rat hepatic microsomal system, which contains biotransformation enzymes, to catalyze lenvatinib oxidation in vitro. All hepatic microsomes isolated from rats generated O-desmethyl lenvatinib ( Fig. 1), which was identified by mass spectroscopy as described earlier (14). Microsomes from untreated rats and from rats treated with CYP2B (PB), CYP2E (ethanol), and CYP3A (PCN) inducers generated the second metabolite, lenvatinib N-oxide ( Fig. 1). Its structure was confirmed by mass spectroscopy and using a synthetic standard, as described earlier (14). The formation of both lenvatinib metabolites was dependent on NADPH. The same two metabolites, among others, were found in the urine, feces, and bile of rats in vivo after lenvatinib administration (39).

Fig. 1. Sample chromatogram from HPLC analysis of lenvatinib incubation with liver microsomes from rats pretreated with pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile in the presence of NADPH (black line) and without this cofactor (red line).

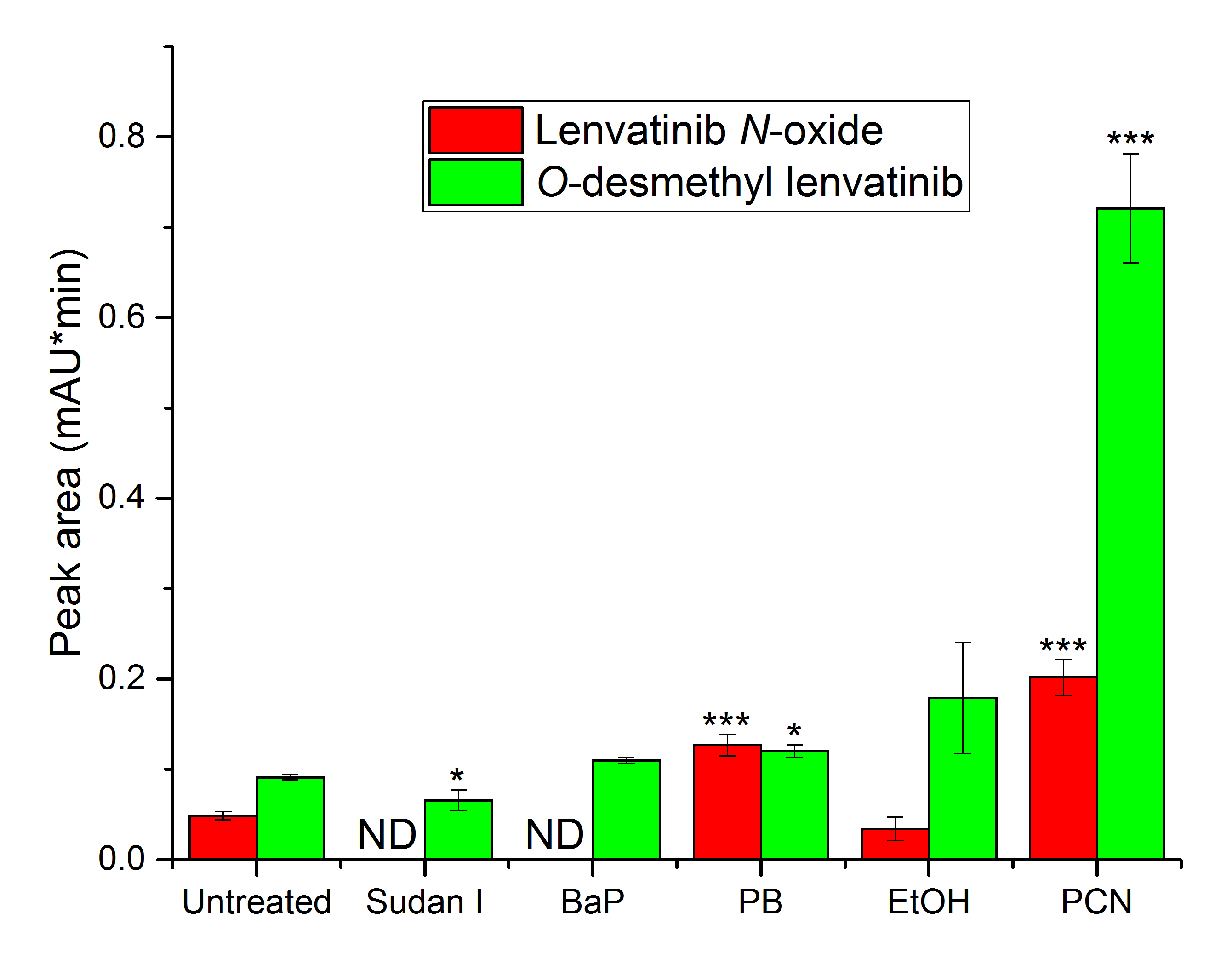

Pre-treatment of rats with specific cytochrome P450 inducers affected the amount of metabolites formed in vitro by liver microsomes isolated from these rats ( Fig. 2). The primary metabolite formed during lenvatinib oxidation is O-desmethyl lenvatinib. In comparison with microsomes from untreated rats, the amount of O-desmethyl lenvatinib was higher for all specific inducers except Sudan I, the inducer of CYP1A1 (25), with statistical significance ( p < 0.05) in the case of microsomes from rats treated with PB and PCN. Microsomes from rats exposed to the inducer of CYP3A, PCN (40), were the most efficient in the formation of this metabolite. O-desmethyl lenvatinib is also the main metabolite generated by human liver microsomes, as shown recently (14). In addition, CYP3As appear to be the primary enzymes that catalyze the formation of the second metabolite, lenvatinib N-oxide. Hepatic microsomes from rats exposed to PCN as well as another inducer, PB, mediated the increased production of lenvatinib N-oxide ( p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Pretreatment of rats with CYP1 inducers (Sudan I and BaP) resulted in a complete loss of the ability of liver microsomes to form this metabolite in vitro. The efficiency of producing the metabolite by rat liver microsomes was decreased due to CYP2E1 induction by ethanol when compared to microsomes from untreated rats. However, this change was not statistically significant (Fig. 2). Lenvatinib N-oxide was not observed after incubating human liver microsomes with lenvatinib in our previous study, although this metabolite was formed by recombinant CYP3A4 (14), the most abundant CYP in human liver (41), and identified as a metabolite of lenvatinib formed in vitro by human fraction S9 in another study (42). The third metabolite, N-descyclopropyl lenvatinib, has been previously detected upon human microsome incubation with lenvatinib (14), but not in this study when incubating rat microsomes with lenvatinib.

Fig. 2. Lenvatinib oxidation by hepatic microsomes from untreated rats and from rats pretreated with several CYP inducers (BaP ‒ benzo[ a]pyrene; PB ‒ phenobarbital; EtOH ‒ ethanol; PCN ‒ pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile). Values expressed as mean ± SD of three independent in vitro incubations ( n = 3). * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001 – significantly different from untreated rats. ND – not detected.

Lenvatinib oxidation by recombinant rat cytochromes P450

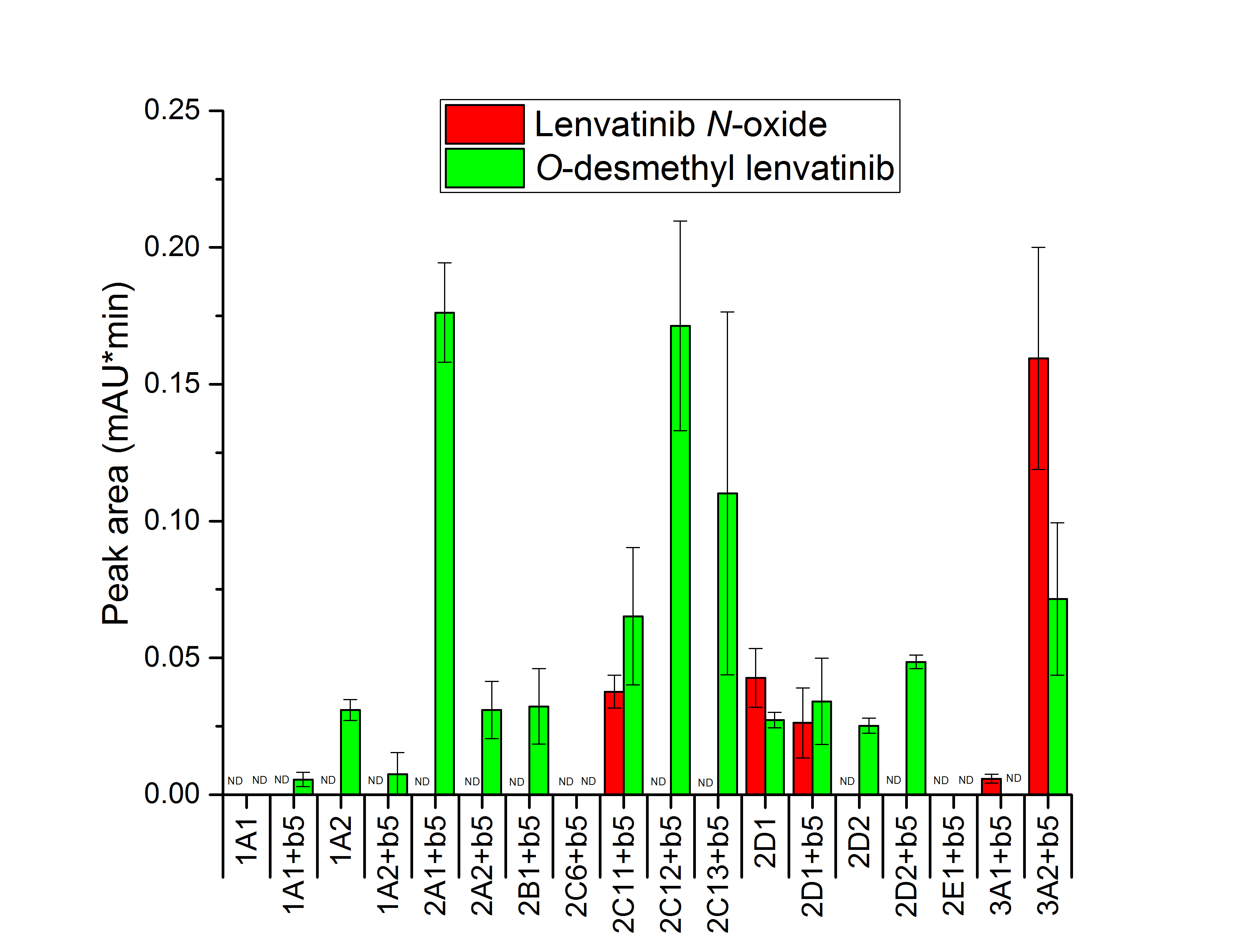

Recombinant rat CYPs produced in SupersomesTM were used to identify specific enzymes involved in lenvatinib oxidation. Fourteen rat cytochromes P450 were tested to study their lenvatinib oxidation potential. Most of them were available only when co-expressed with cyt b5. Conversely, CYP1A1, 1A2, 2D1, and 2D2 were available only without cyt b5. Therefore, cyt b5 was added to these four CYPs to reach a CYP-to-cytochrome b5 molar ratio of 1 to 5, as in Supersomes containing cyt b5.

Eleven of the fourteen cytochromes P450 tested in this study oxidized lenvatinib to O-desmethyl lenvatinib ( Fig. 3). Some cytochrome P450 enzymes are expressed in rat liver in a sex-dependent manner and subject to complex developmental regulation and endocrine control. The most abundant metabolic enzymes in rat liver are CYPs of family 2, a predominantly 2C, of which most enzymes show sex-dependent expression (43). The most efficient enzymes were CYP2A1 and 2C12. CYP2A1 is the predominant form in adult female rats. The sex difference in the amount of this enzyme emerges during the weaning period when CYP2A1 levels decline significantly (60–70 % decrease) in males, but not in females (44, 45). The second most efficient enzyme CYP2C12 is constitutively expressed in female, but not male, rats (46, 47). Male rats express CYP2C11 (47, 48). CYP2C11 was significantly less potent in catalyzing the formation of O-desmethyl lenvatinib ( p < 0.05) than CYP2C12, but generated, nevertheless, lenvatinib N-oxide, which was not formed by CYP2C12. Another male-specific cytochrome P450 CYP2C13 (43), is also efficient in lenvatinib oxidation to O-desmythyllenvatinib, but shows large variability. CYP1A1 generated this metabolite only in the presence of cytochrome b5. Cyt b5 also stimulated the production of this metabolite by CYP2D2 ( p < 0.01). Controversially, cyt b5 decreased O-desmethyl lenvatinib production by CYP1A2 ( p < 0.01).

The second metabolite, lenvatinib N-oxide, was generated by CYP2C11, 2D1, and 3A1/2 ( Fig. 3). CYP3A2, which is also male-specific (49), was the most efficient enzyme, whereas CYP3A1 was the least efficient of these four CYPs in generating this metabolite. Moreover, CYP3A1 was the only enzyme among these four enzymes that failed to yield O-desmethyl lenvatinib. These enzymes may also account for the increased formation of both lenvatinib metabolites mediated by microsomes from phenobarbital-treated rats, which in addition to CYP2B can induce expression of this CYP subfamily via constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) (50).

Fig. 3. Lenvatinib oxidation by recombinant rat CYPs. Values expressed as mean ± SD of three independent in vitro incubations ( n = 3). ND – not detected.

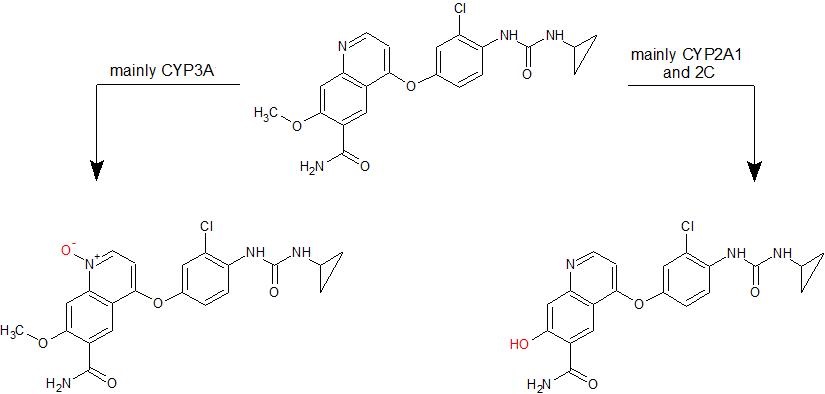

Based on the results, the scheme of lenvatinib metabolism in rats was proposed (Fig. 4). These results also corroborate the findings of experiments with human CYPs, where CYP1A was responsible for producing only O-desmethyl lenvatinib, and the most active enzyme was CYP3A4 (14). However, recombinant rat hepatic CYP2C enzymes were more active in the oxidation of lenvatinib than human ones. Nevertheless, the representation of CYP2C enzymes and their content in rat and human liver cells differ (32), making comparisons difficult due to interspecies differences. Three of four tested rat CYP2C enzymes were able to oxidize lenvatinib, whereas only CYP2C19 was efficient among all human hepatic CYP2C enzymes (14). Human CYP2C19 is an ortholog of rat CYP2C6 (51), the only inactive CYP2C of the enzymes tested in this study. Nevertheless, CYP2C19 is also homologous to the other rat CYP2Cs (51), and because CYP2Cs are the most abundant CYP enzymes in rat liver (43, 52), the role of CYP2Cs in lenvatinib metabolism in rats cannot be ignored and, in fact, should be carefully analyzed in comparison with its role in humans.

Fig. 4. Proposed schema of lenvatinib oxidation by rat CYPs.

Oxidation of lenvatinib by hepatic microsomes of rats pretreated with lenvatinib

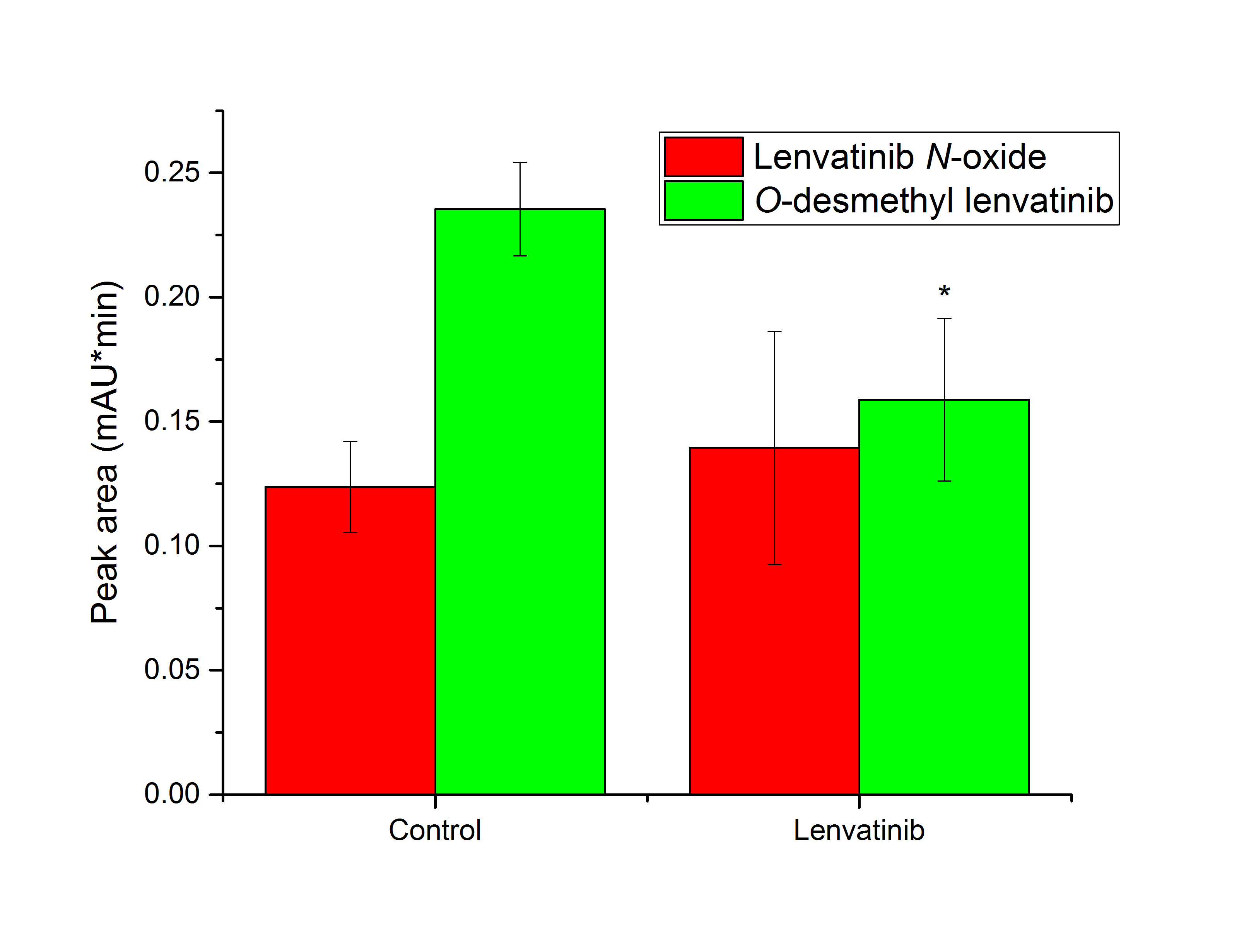

We further investigated whether exposure of rats to lenvatinib itself affects the ability of microsomes isolated from their liver to metabolize lenvatinib in vitro. A single, relatively high dose of lenvatinib (30 mg kg–1), based on previous research aimed at studying lenvatinib metabolism in experimental animals in vivo (39, 53), was administered by gavage to a group of male Wistar rats to see the immediate effect of the drug on selected cytochromes P450. For long-term treatment, it is recommended that patients with differentiated thyroid cancer take 24 mg lenvatinib orally once a day. Many agents induce biotransformation enzyme expression after a single dose, e.g. β-naphthoflavone (24), dexamethasone (54), or albendazole (55), so we chose this experimental approach for a first approximation. We found that O-desmethyl lenvatinib production was significantly reduced compared to its production by microsomes of control animals (p < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 5. However, there was no difference between control and lenvatinib-treated rats in the amount of lenvatinib N-oxide, the second metabolite, formed by liver microsomes (Fig. 5). The male animal model was chosen because in in vitro lenvatinib oxidation experiments there were used microsomes from male rats exposed to specific CYP inducers. Considering the results showing the high efficacy of some female-specific supersomal CYP enzymes in lenvatinib metabolism (Fig. 3), further studies could be conducted to assess the effect of lenvatinib on the expression of these enzymes in female rats.

Fig. 5. Lenvatinib oxidation by hepatic microsomes from control rats and rats pretreated with lenvatinib. Values expressed as mean ± SD of three independent in vitro incubations ( n = 3). * p < 0.05 – significantly different from control rats.

Cytochrome P450 expression and activity in the liver of rats exposed to lenvatinib

CYP1 family

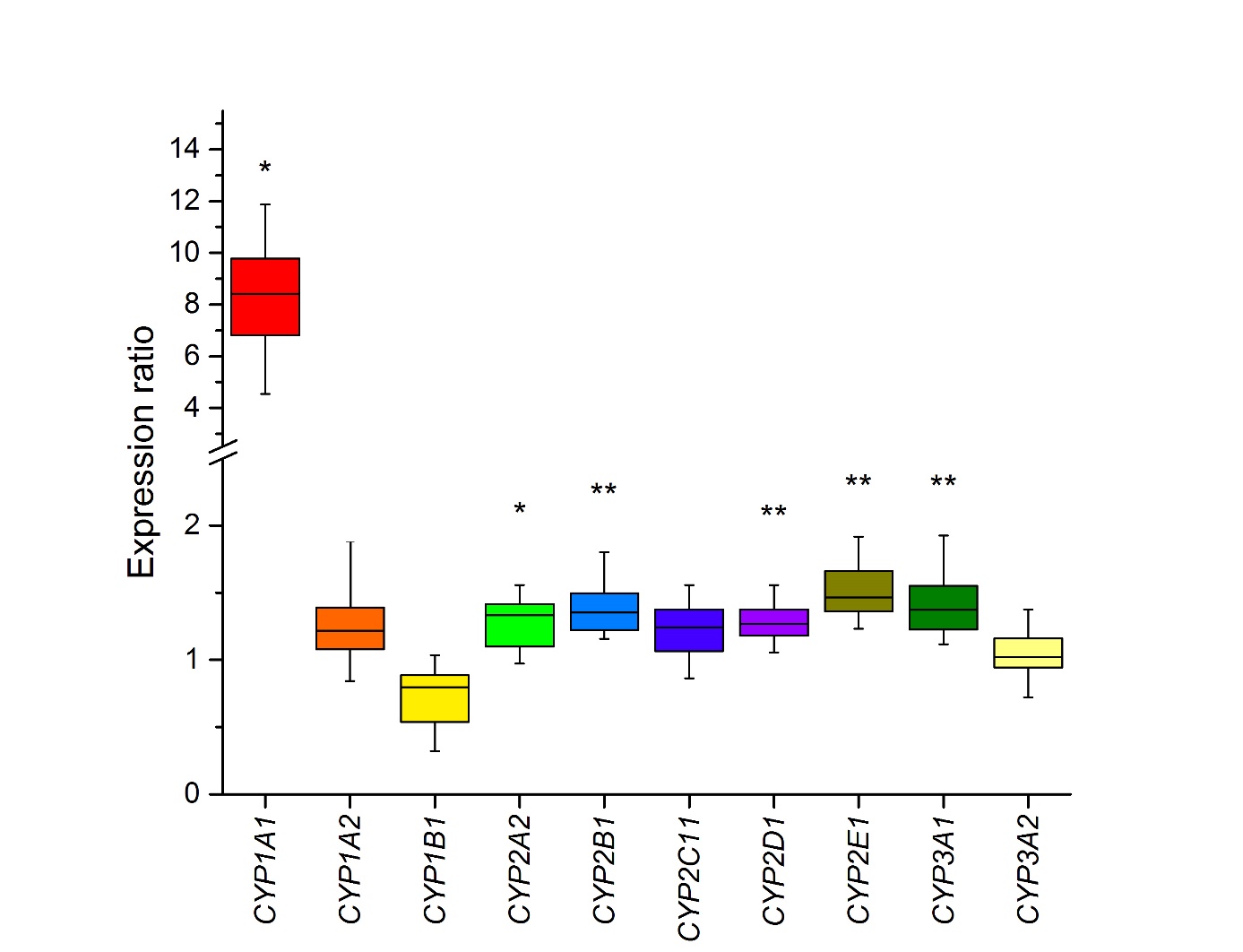

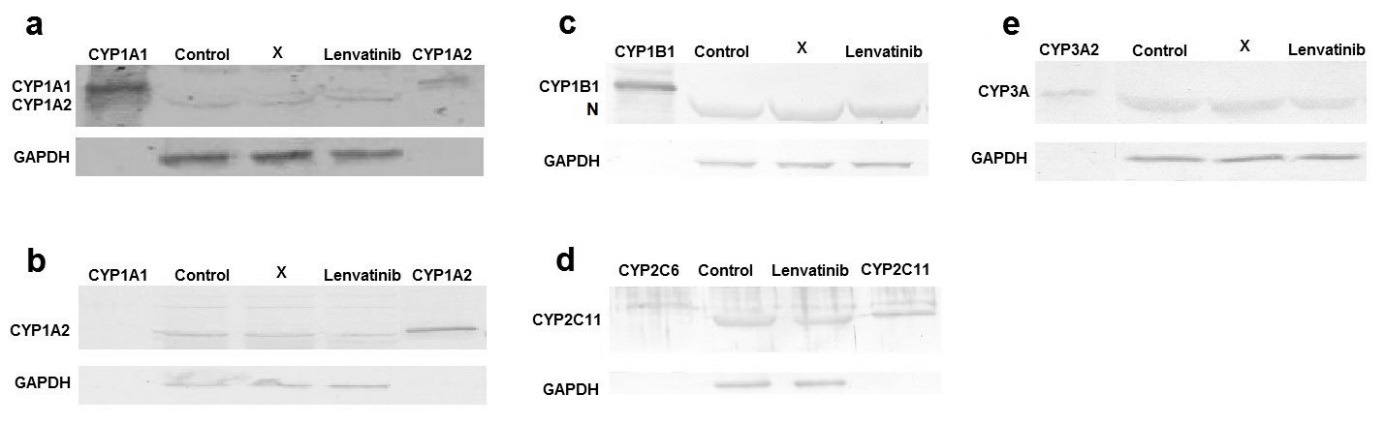

The transcription of CYP1 genes, controlled by the Ah-receptor (56), was tested due to the high efficiency of human CYP1A1/2, which are orthologous to rat enzymes, in the oxidation of lenvatinib (14) even though CYP1A1 expression is very low in the liver (57). The results from quantitative PCR showed that the livers of rats pre-treated with lenvatinib contained elevated mRNA levels of CYP1A1 (8.1-fold, p < 0.05; Fig. 6). To confirm the effect of lenvatinib on CYP1 expression, the protein levels of CYPs were also analyzed by Western blotting using consecutive immunodetection with specific antibodies ( Fig. 7a–c). In comparison with the liver of control animals, lenvatinib administration also increased CYP1A1 protein expression ( Fig. 7a, which was almost undetectable in the liver microsomes of control rats but a faint band corresponding to CYP1A1 was clearly visible in the sample from rats exposed to lenvatinib. CYP1B1 expression in the liver of lenvatinib-treated rats was similar to that in control rats ( Fig. 6), and its protein expression was not detected in the liver of either group of animals ( Fig. 7c).

Fig. 6. Box plot diagrams of gene expression. The top bar is the maximum, the lower bar is the minimum, the top of the box is the upper or third quartile, the bottom of the box is the lower or first quartile, and the middle bar is the median value. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 – significantly different from control rats ( n = 4).

Fig. 7. Western blot analysis of: a) CYP1A1; b) CYP1A2; c) CYP1B1; d) CYP2C11 and e) CYP3A in the liver of control rats and of rats treated with lenvatinib. Glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. X – line unrelated to the manuscript. N – nonspecific protein detected by CYP1B1 antibody.

Although CYP1A1 gene and protein expression increased after lenvatinib administration ( Fig. 6 and 7a), its 7-ethoxyresorufine- O-deethylation activity (EROD), a marker of CYP1A1 activity (34), differed only minimally, albeit significantly (1.2-fold; p < 0.05), between microsomes isolated from treated and control animals ( Table I). Moreover, the amount of 4’-OH Sudan I, the predominant metabolite formed by rat CYP1A1 from another probe substrate for CYP1A1 (35), was significantly (1.5-fold, p < 0.01; Table I) higher in hepatic microsomes from lenvatinib-treated rats incubated with Sudan I than that in microsomes from control animals. The levels of another metabolite, 6-OH Sudan I, did not significantly differ between liver microsomes from untreated and lenvatinib-treated rats incubated in vitro with this dye. Hepatic microsomes from rats treated with lenvatinib showed a significantly (1.6-fold; p < 0.05) higher activity to 7-methoxyresorufine, than microsomes from untreated rats ( Table I). 7-Methoxyresorufine- O-demethylation activity has been used as a marker reaction for CYP1A2 (34), but this reaction is also catalyzed by CYP1A1 and several other CYPs (58). However, there was no significant change in CYP1A2 protein expression induced by lenvatinib (Fig. 7b), nor was there an increase in CYP1A2 gene expression (Fig. 6). Because gene and protein expression of CP1A2 remained unchanged, the higher MROD activity of hepatic microsomes of lenvatinib-treated rats might have been caused by the nonspecificity of the reaction and reflected the higher activity of CYP1A1, as confirmed by Sudan I hydroxalation at the 4’ position and EROD.

Table I. Enzyme activities of CYP1A1/2, 2C11, and 3A1/2 towards their probe substrates in hepatic microsomes of control rats and of rats exposed to lenvatinib

ap < 0.001,b p < 0.01,c p < 0.05 significantly different from control rats; ( n = 3)

CYP3 family

The main human enzyme responsible for the oxidation of lenvatinib (14) and other TKIs and drugs (15, 16, 59–63) is CYP3A4, whose rat ortholog/homolog is CYP3A2/1 (51). CYP3 genes are controlled by the pregnane X receptor (28). However, the rat may not be a good model to study CYP3A4 induction in humans because CYP3A1 is not induced by the same inducers (64, 65). CYP3A1 gene expression in the liver was slightly induced (1.4-fold, p < 0.01) by lenvatinib, whereas CYP3A2 expression was not changed in comparison with the control ( Fig. 6). The observed lenvatinib-induced increase in CYP3A1 gene expression matches the increase in CYP3A4 in human hepatocytes (66). No change in the protein expression of both CYP3As was observed either ( Fig. 7e) even though microsomes from the livers of rats treated with lenvatinib mediated 6 β-hydroxylation of testosterone less efficiently than hepatic microsomes from untreated rats (0.75-fold, p < 0.001, Table I). Whether lenvatinib acts as an irreversible or time-dependent inhibitor of rat CYP3A enzymes could be the subject of further detailed investigation as human and rat CYP3As inhibition by lenvatinib has been observed previously (67, 68). CYP3A inactivation may hence explain why metabolite formation during in vitro oxidation of lenvatinib by microsomes from lenvatinib-pretreated rats is lower than that by microsomes from control rats (Fig. 5).

CYP2 family

The CYP2 family is the largest and most diverse CYP family in humans and rats (32). Of the five tested genes ( CYP2A2, 2B1, 2C11, 2D1, and 2E1) of the major CYP2 enzymes responsible for the biotransformation of xenobiotics, four genes showed a small, but significant, increase in hepatic expression after lenvatinib administration to rats ( Fig. 6). CYP2E1 reached the highest expression induction (1.5-fold, p < 0.01). Since rat CYP2Cs were efficient in oxidizing lenvatinib (Fig. 3), we studied its potential impact on the expression of the most abundant enzyme in rat liver, CYP2C11 (32). However, there were no changes in the mRNA, protein, or activity levels of this CYP after lenvatinib administration. CYP2C expression in rat liver is regulated primarily hormonally (69) and there are many drugs that reduce its expression by affecting hormone levels (70). The other most active enzymes in lenvatinib oxidation (CYP2A1 and 2C12) are female-specific, thus the protein expression and activity of these enzymes were not examined because our experiments were performed in male rats.

CONCLUSIONS

The major metabolite formed in vitro from lenvatinib by rat liver microsomes was identified as O-desmethyl lenvatinib, a prominent metabolite generated also by human liver microsomes. It is generated by several recombinant CYPs, most efficiently by CYP2A1 and CYP2C12/13. Another metabolite, lenvatinib N-oxide, was also identified in some samples. The enzyme primarily involved in its formation is CYP3A2, which may be the most important enzyme of lenvatinib metabolism also in the rat hepatic microsomal system. Hepatic microsomes from rats exposed to lenvatinib showed decreased efficiency in oxidizing lenvatinib to O-desmethyl lenvatinib, suggesting that lenvatinib affects the expression and/or activity of cytochrome P450 or other microsomal phase I and phase II biotransformation enzymes potentially involved in its metabolism. Lenvatinib administration to rats slightly increased the gene expression of several hepatic CYPs, particularly CYP1A1. Small, but significant changes in the protein expression and catalytic activity of this enzyme were also observed. Nevertheless, this does not seem to be the reason for the observed decrease in O-desmethyl lenvatinib formation mentioned above.

The differential lenvatinib metabolite profiles formed in vitro between rat and human hepatic microsomes or respective CYP enzymes underscore the importance of species-specific considerations in drug metabolism studies. Differences in the representation of CYP enzymes important for lenvatinib metabolism in the liver of two species may also play a role in the metabolic fate of lenvatinib. In addition, the use of lenvatinib may lead to changes in the levels of these enzymes, more specifically CYP1A1, although this effect must be further studied for long-term low-dose usage. Drug-drug interactions should be carefully monitored when lenvatinib is administered in combination with other drugs.

Ethical approval. – This study was conducted in accordance with the Act on Protection of Animals against Cruelty (246/1992) and the Decree on Protection of Experimental Animals (419/2012, Ministry of Agriculture, Czech Republic) under the experimental protocol 48/2015 approved by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (July 29, 2015) on the recommendation of the Expert Committee for Ensuring the Welfare of Experimental Animals of the National Institute of Public Health.

Acknowledgements. – We would like to thank Dr. Carlos Henrique Vieira Melo for editing the English of the manuscript.

Funding. – This research was funded by the Czech Science Foundation (grant 15-02328S).

Conflict of interests. – The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript writing; or in the decision to publish the results.

Authors contributions. – Conceptualization, H.D. and R.I.; methodology, H.D., Š.D. and R.I.; formal analysis and investigation, S.J., K.K., P.Z., J.D. and Š.D; writing – original draft preparation, R.I.; writing – review and editing, H.D. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.