Introduction

Catapodium rigidum (L.) C.E. Hubb. (Desmazeria rigida (L.) Tutin), fern grass or rigid-fescue (Poaceae family), is one of the most common synanthropic weed species in the Mediterranean region. It occurs in dry stony grasslands, particularly in ruderal places along roadsides, and municipal areas (Coste 1906, Fiori 1923, Jávorka 1925, Horvat et al. 1974). A recent study by Jasprica et al. (2017) found that this species is one of the most widespread weed species in railway stations in the North-Western Balkans. Catapodium rigidum s. str. has a Mediterranean-Atlantic distribution (Rikli 1943–1948, Meusel et al. 1965, Tutin et al. 1980). However, fern grass has been known to occur adventitiously in areas far from its original range, such as Asia, North and South America, Southern Africa, Australia (Clark 1974, Bhat et al. 2021, GBIF 2023). The species is considered indigenous to a small part of Switzerland (between Sézegnin and Soral), but introduced occurrences have also been long known in several large towns and cities, at railway stations, along railway lines, and in several cities in Germany (Hegi 1935, Buttler et al. 2018). Very few occurrences have been reported in Central Europe, east of Germany. Its casual occurrence was reported for the first time from Graz, Austria (Melzer 1954). The first report of this species in the Czech flora was almost 50 years ago by Dostál (1989), but there have been no confirmations. In 2009, Stöhr et al. reported a second observation of fern grass in Austria, in the surroundings of Salzburg (the community of Lamprechtshausen).

Old data (published or herbarium) reported occasional introductions of many Mediterranean species in Hungary. An accelerated spread of such plants has been observed recently (see Schmidt et al. 2016, Kun et al. 2023). However, in the BP herbarium specimens of C. rigidum originated from 19th century and the plants were grown from seeds in the botanical garden. Neither Borbás (1891) nor Filarszky (1894) mentioned it in their related papers. The species was first observed in Hungary by Solymosi (2008) along the main road near Becsehely (Zala County, Western Hungary). A decade later, Schmidt (2019) reported a finding of the species on the Szombathely bypass (Vas County, Western Hungary). In recent years, the species has been found in many locations, particularly in the western part of the country (Transdanubia). While the manuscript of this study was being written, Rigó et al. (2023) reported the species from the capital (Budapest) in a single locality. The aim of our study is to provide a comprehensive summary of the current distribution of C. rigidum in Hungary, based on both published and unpublished data.

Material and methods

All authors conducted independent fieldwork, examining roadside vegetation and urban areas in various regions of the country. We recorded the geographic coordinates of the occurrences using GPS devices. A list of the sites is provided, along with the observation dates, geographical coordinates, grid numbers in the Central European Flora Mapping System (Niklfeld 1971), estimated number of individuals, and occurrence conditions. The specimens collected from the new sites in Hungary have been deposited in the BP and JPU Herbaria (Thiers 2024).

Results

The oldest specimens of Catapodium rigidum collected in Hungary were obtained from plants grown from seeds sown in a botanical garden (leg. Fekete, 30.10.1903, culta in h. bot. Budapest BP 313807, 408777). Recent spontaneous occurrences are summarised in Tab. 1.

Tab. 1. Introduced occurrences of Catapodium rigidum found in Hungary until the end of 2023. CEU = grid number of the Central European Flora Mapping System (Niklfeld 1971).

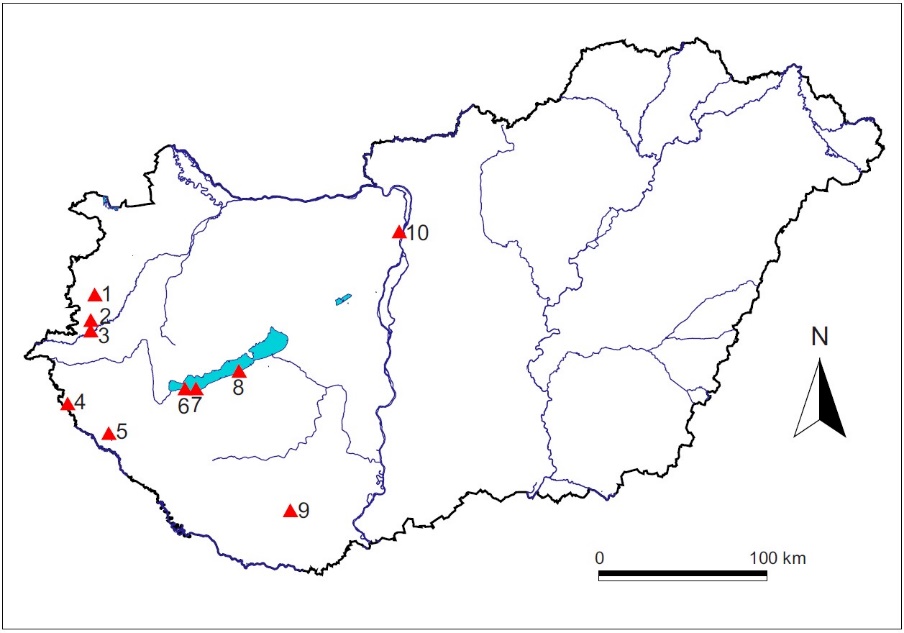

The distribution pattern of the species in Hungary (Fig. 1) indicates a spread in Western and Southern Transdanubia. The species was predominantly found in high-traffic locations, such as main roads and popular tourist areas.

Fig. 1. Current known occurrences of Catapodium rigidum in Hungary (December 2023). The red triangle shows the places where Catapodium rigidum was found: 1 – Szombathely, 2 – Egyházasrádóc, 3 – Körmend, 4 – Rédics, 5 – Becsehely, 6 – Balatonmáriafürdő, 7 – Balatonfenyves, 8 – Balatonszemes, 9 – Pécs, 10 – Budapest.

Discussion

Our presumption is that the presence of the fern grass in Hungary can be attributed to human activities, particularly international transport and tourism. The type of dispersal can be classified as anthropochory and agochory, as described by van der Maarel (2005) and Schulze et al. (2005). Where heavy traffic occurs on main roads (roadsides, roundabouts, pavements), the vector could be mainly motor vehicles carrying propagules on pieces of gravel. However, small populations found at sites where waste accumulates (e.g. Balatonszemes harbour; Pécs, at the base of buildings in a one-way street) suggest that lesser amounts of propagules may have been transported by human clothing and tools. The current new occurrences may be the result of independent introductions.

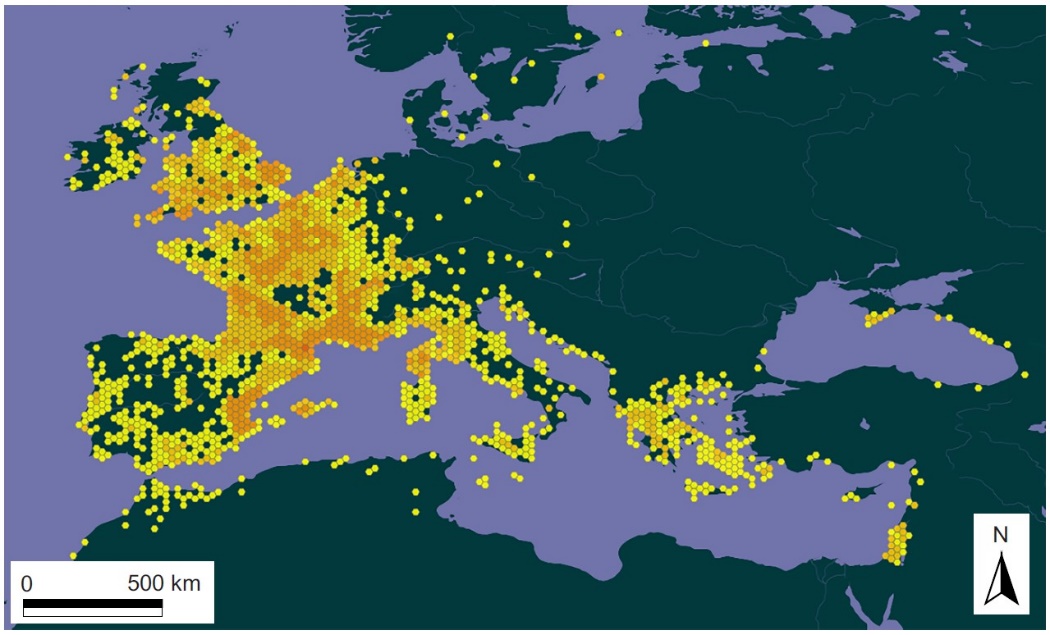

Although mentioned as a synanthropic species by Hegi (1935), its recent distribution in Europe (Fig. 2. GBIF) is rather dispersed and scattered outside of its original climatic requirements, specifically outside of the regions with oceanic and Mediterranean climates.

Fig. 2. Distribution of Catapodium rigidum in Europe based on GBIF data (2 October 2023). The dots show the reported occurrences of C. rigidum, the shades of yellow (from light to dark) reflect the amount of data detected.

Its natural distribution limit is almost identical to the January 0 C° isotherm (Michael 2021, p. 52.). Previous occurrences of this species in Central Europe were sporadic, and for a long time, its presence was not confirmed in Austria and in the Czech Republic (Melzer 1954, Dostál 1989, Stöhr et al. 2009, Pyšek et al. 2012). The establishment of the species in continental areas has been restricted, due to the limiting effect of winter frost (see Manley 1958, Grimm et al. 2008). However, according to the current climate change trends in the Pannonian region (Bartholy et al. 2014), the species is predicted to become established in Central Europe and other areas with a humid continental climate (Beck et al. 2018).

Currently, there are limited and conflicting data regarding the survival of plants in the stands. In the city of Szombathely, it was first discovered in 2017, disappeared for a year, and then reappeared in 2019, remaining present ever since. This observation suggests that if the habitat is suitable self-sustaining populations may develop. Mild winters do not appear to be a limiting factor if there are no periods of heavy frost. However, not all of the stands known for more than two years can be confirmed in the coming year. For instance, one of the most abundant populations found in 2022 (Egyházasrádóc village) was not observed on the roadside during the same period the following year. Given that the winter between the two field surveys of the site was the second mildest in the last 100 years (Szolnoki-Tótiván 2023), it is necessary to consider other limiting factors that may affect the survival of the introduced plants. Occasional mass emergence may occur due to extensive propagule introduction after winter. However, despite significant mass seed dispersal, germination in the following early spring may not be possible due to the high osmotic stress on roadside verges (Davison 1971). According to the Ellenberg-type indicator values database (Tichý et al. 2023), the species is presumably a glycophyte (salt-sensitive), so the use of salt to de-ice main roads is likely to reduce its long-term viability. The experimental confirmation by Talbi Zribi et al. (2018) also supports the strong salt sensitivity of C. rigidum when planted for forage in arid areas. Additionally, its long-term survival on main road verges may be reduced because C. rigidum is an annual C3 species. Its phenology is characterised by early spring germination, when the effect of winter salting is still strong and the leaching effect of precipitation is still weak. It is uncertain whether a population, even a relatively large one, can be considered self-sustaining in the future. However, due to the ever-increasing flow of traffic from the Mediterranean, the frequent introduction of its propagules is almost inevitable. It is possible that urban weed vegetation not subject to salting and de-icing will be more likely to have persistent, established populations, even if these are smaller. The aforementioned increases in the chance of establishment are already assumed for many species with similar climatic requirements and have shown recent area expansion (Bátori et al. 2012, Schmidt et al. 2016, Bauer 2018, Mesterházy et al. 2021, Bauer and Verloove 2023, Kun et al. 2023). It is expected that C. rigidum will continue to occur and spread in temperate continental areas of Central Europe, particularly along busy roads and in towns, with an increasing number of observations in the coming years.