1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past few years, the issue of urban tourism has gained prominence in political, academic and civil society debate, in particular, due to the explosive growth of short-term rentals in many major European and North American cities (Ashworth and Page 2011;Davidson and Lees 2010;Guttentag 2015;Crommelin et al. 2018;Adamiak 2018,2019;Oskam 2020). According toPereira (2020), although Lisbon quantitatively stands out in the global short-term rentals expansion, both in absolute and relative numbers (Adamiak 2018,2019), the discussion about the impacts of the excessive concentration of short-term rental is dominated by some specific North America and European cities (e.g. Schäfer and Braun 2016;Hughes 2018;Crommelin et al. 2018;Ferreri and Sanyal 2018;Freytag and Bauder 2018;Aznar et al. 2018;Aguilera et al. 2019;Jiao and Bai 2020;Miquel-Àngel et al. 2020;Celata and Romano 2020;Mikulić et al. 2021). Despite Lisbon is an important European urban destination, the Portuguese capital has gone unnoticed by the international literature, although this issue has been subjected to numerous scientific studies in Portugal itself (see section 4).

The objective of this paper is to analyse the growth of tourism in Portugal, with a focus on short-term rentals. The paper is organised in the following way: a) section 1, documenting growth trends in tourism at the global level and focussing on the case of Portugal; c) section 2, looking at growth in the short-term rentals market and its multidimensional impact; d) section 3, undertaking a spatial analysis [1] of the distribution of short-term rental units, with first a national analysis by NUTS [2]. II region and then an analysis of the municipality of Lisbon; e) section 4, seeking to interpret the possible consequences of the excessive concentration of short-term rentals in urban areas

The spatial analysis (section 3) and the discussion (sections 4 and 5) aspires to contribute to a greater knowledge of the spatial patterns of short-term rental units in Portugal and in the municipality of Lisbon and to illustrate how the excessive concentration of short-term rentals produces multidimensional and non-linear externalities that need to be analysed and recognised.

2. TOURISM AND DOMINANT TRENDS

In the 21st century, tourism has become one of the most important economic activities (Becker 2013;Page and Connel 2020;Oskam 2020). In recent decades, various cities, regions and even countries have relied on the tourism sector as the big opportunity for economic growth. At present, tourism is important for job creation and territorial development and is a major component of gross domestic product (GDP) in countries that have invested in this sector.

The factors that have fostered the growth of tourism are well known and include the opening of frontiers, the expansion of air travel (especially low-cost flights), the emergence of online accommodation booking platforms, among other factors that are related to globalisation and the free movement of people across borders.

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), the tourism sector in 2019 accounted for 10.3% of global GDP. Also, at global level, it should be noted that the tourism sector growth of 3.5% at the same year, slightly faster than the overall growth in the global economy, which was 2.5% (WTTC 2020a).

Europe is the world’s top tourist destination (WTTC 2020a). The tourism sector plays a very important role in the economy of several European countries, above all in Central and Mediterranean Europe (Williams and Lew 2014;Silva et al. 2018;WTTC 2020a). Looking specifically at some indicators at the European Union level [3], the number of “establishments and bed-places” [4] grew by around 355,000 in 2008, to approximately 620,000 in 2019 (growth of 74%). In the case of Portugal, the growth was still faster, with the number of tourist accommodation establishments rising from 2,351 in 2008 to more than 7,000 in 2019 (growth of 198%).

Another indicator of how the tourism trade has grown in Europe is the “arrivals of residents/non-residents at tourist accommodation establishments”[5], with an estimate for the European Union in 2018 of 253,267,989 arrivals, rising in 2019 to 406,907,066 (growth of 60%). Looking again at Portugal, it can easily be understood that the Portuguese economy became increasingly reliant on the tourist trade during the 2010s, with the estimated number of arrivals fewer than 7 million in 2008 but rising to 16 million a decade later.

2.1. Tourism trends in Portugal

Like many other countries, Portugal has experienced a tourism boom in recent times. In a global study carried out by the WTTC, the section on Europe includes a part dedicated to Portugal, in which it is stated that the tourism sector in 2019 generated 16.5% of national GDP (one of the highest percentages in Europe, and well above the global average of 10%) (WTTC 2020a).

According to the same organisation, the Portuguese tourism sector in 2019 grew by more than 4% (versus 1.6% real GDP growth) and it accounted for 900,000 jobs (18.6% of total employment)[6] (WTTC 2020a,2020b). Meanwhile, according to Statistics Portugal, the total number of tourists has been increasing continuously in the 2010s, with new record highs for arrivals and overnight stays year after year (INE 2019). However, there was a clear deceleration in 2018, which could indicate a new period of stabilisation (INE 2019).

Tourism in Portugal is related to leisure spending (85%) and dominated by foreign tourists (70%), notably from the United Kingdom (14%), Spain (14%), France (12%), Germany (11%) and Brazil (6%) (WTTC 2020a,2020b). Indeed, it was foreign tourists who drove growth in Portuguese tourism in the 2010s (INE 2019). It is also necessary to highlight that in recent years, Portugal has often been cited as a case study in global reviews of tourism (e.g. WTTC 2018,2019,2020a).

Along with the growth in tourism, other related sectors also showed an increase in activity, such as hospitality, transports, golf, arts and culture, and also the rehabilitation of existing buildings (e.g. turning them into short-term rentals), which contributed to turnover in the civil construction and property sectors (Cachinho 2019;Cabral 2019).

From a qualitative point of view, the growth in tourism in Portugal is related a well-defined political strategy that in the last decade has sought to replace traditional seasonal tourism (above all in the Algarve region) (Silva et al. 2018) with an activity that is spread over the whole year and is not so dependent on sun/beach tourism.

In recent years, international macroeconomic studies (e.g. OECD 2019) and specific analyses of the tourism sector have stressed the importance of this activity for the economic recovery that followed the financial bailout that Portugal exited in 2014. According to these studies, the tourism sector played a very important role boosting Portugal’s economy and exports in the wake of the financial crisis (Bento 2016;Pereira and Teixeira 2017;Araújo 2017;Silva 2019;OECD 2019).

However, as we shall see in the next few sections, the public debate (political, academic and in civil society) on the multidimensional impacts of tourism has grown significantly, above all where the impacts of the excessive concentration of short-term rentals in the historic centres of the cities are concerned. And the question now arising is: how much is too much?

2.2. Short-term rentals: growth and concerns

Short-term rentals have emerged of late as a new area for investment and business, becoming one of the main engines of contemporary tourism (Ashworth and Page 2011;Davidson and Lees 2010;Guttentag 2015;Crommelin et al. 2018). Short-term rentals are aimed at tourists who want to avoid conventional hotel accommodation and seek a more informal tourism experience that is closer to that of locals. At the same time, short-term rentals are associated with the emergence of new concepts such as the ‘sharing economy’, ‘city branding’ and the use of online platforms, which are particularly popular with a younger generation (millennials), not only to reserve accommodation (e.g. Booking.com, Airbnb) but also to share their leisure experiences on social networks (e.g. Facebook, Instagram) (Botsman and Rogers 2010;Belk 2014;Zervas et al. 2017;Hamari et al. 2016).

The boom in short-term rentals has triggered various criticisms, especially in major cities in Europe and North America (Ashworth and Page 2011;Davidson and Lees 2010;Guttentag 2015;Crommelin et al. 2018;Adamiak 2018,2019). These analyses note that the excessive spatial concentration of short-term rentals may be associated with classical urban phenomena such as gentrification, the financialisation of housing and touristification (Brenner et al. 2012;Aalbers 2016;Lees et al. 2016;Lees and Phillips 2018;Oskam 2020;Van Heerden et al. 2020;Mikulić et al. 2021). Also, studies identifying negative externalities arising from short-term rentals have looked at the saturation of local infrastructure and implications for the property market (Hoffman and Heisler 2020;Nieuwland and Melik 2020;Miquel-Àngel et al. 2020;Celata and Romano 2020). Meanwhile, social perceptions of excessive concentration and intensification of short-term rentals have triggered various urban tensions and protests on the part social movements against the ‘tourist city’ (Colomb and Novy 2016;Hughes 2018;Chin and Hampton 2020;Vodeb et al. 2021).

The issue of excessive concentration of short-term rentals does not necessarily arise because of the increase in the number of tourists, but rather to the implications that this business model has for Portugal’s residential market. As some studies note, the concept of the sharing economy hides a reality in which short-term rentals do not function merely as complementary income for the property owner, but as informal hotels all year round. In this sense, short-term rentals make use of housing units that are withdrawn from the property market, so reducing the number of homes available to buy or rent, which has direct implications for prices per square metre and which can lead to economic and social transformations in these urban areas under pressure (Hoffman and Heisler 2020).

As we shall see, there has been strong growth in short-term rentals in the centres of Portugal’s main cities, in particular Lisbon and Porto, which has presented new urban challenges and had various economic and social repercussions (Barata-Salgueiro et al. 2017;Carvalho et al. 2019;Rio Fernandes et al. 2018,2019a,2019b;Seixas 2019a,2019b andSeixaset al. 2019). In the next section, official data is used to make observations on the spatial distribution of short-term rental units in Portugal and in the municipality of Lisbon.

3. SHORT-TERM RENTALS – SPATIAL SCENARIOS

3.1. Methodology

Section 3 looks at the spatial distribution of short-term rentals in Portugal, in a geographical perspective that, by using a spatial and multiscale analysis, makes it possible to identify spatial patterns.

From a methodological point of view, it uses spatial data available in the ‘Registo Nacional de Turismo’ (RNT) and the ‘Sistema de Informação Geográfica do Turismo’ (SIGTUR), both managed by the national tourist board (‘Turismo de Portugal’) [7] The information used relates to July 2019 and was explored using geographical information systems in ArcGIS software, employing spatial analysis tools such as ‘standard distance’, ‘standard deviational ellipse’, ‘central feature’ and ‘clustering hotspots’, among others. The observation encompasses around 85,000 geo-referenced points and differentiated items of alphanumeric information, as part of an approach based on statistics and spatial modelling that can be related to research that involves big data and geographic data (Li et al. 2018;Encalada-Abarca et al. 2021).

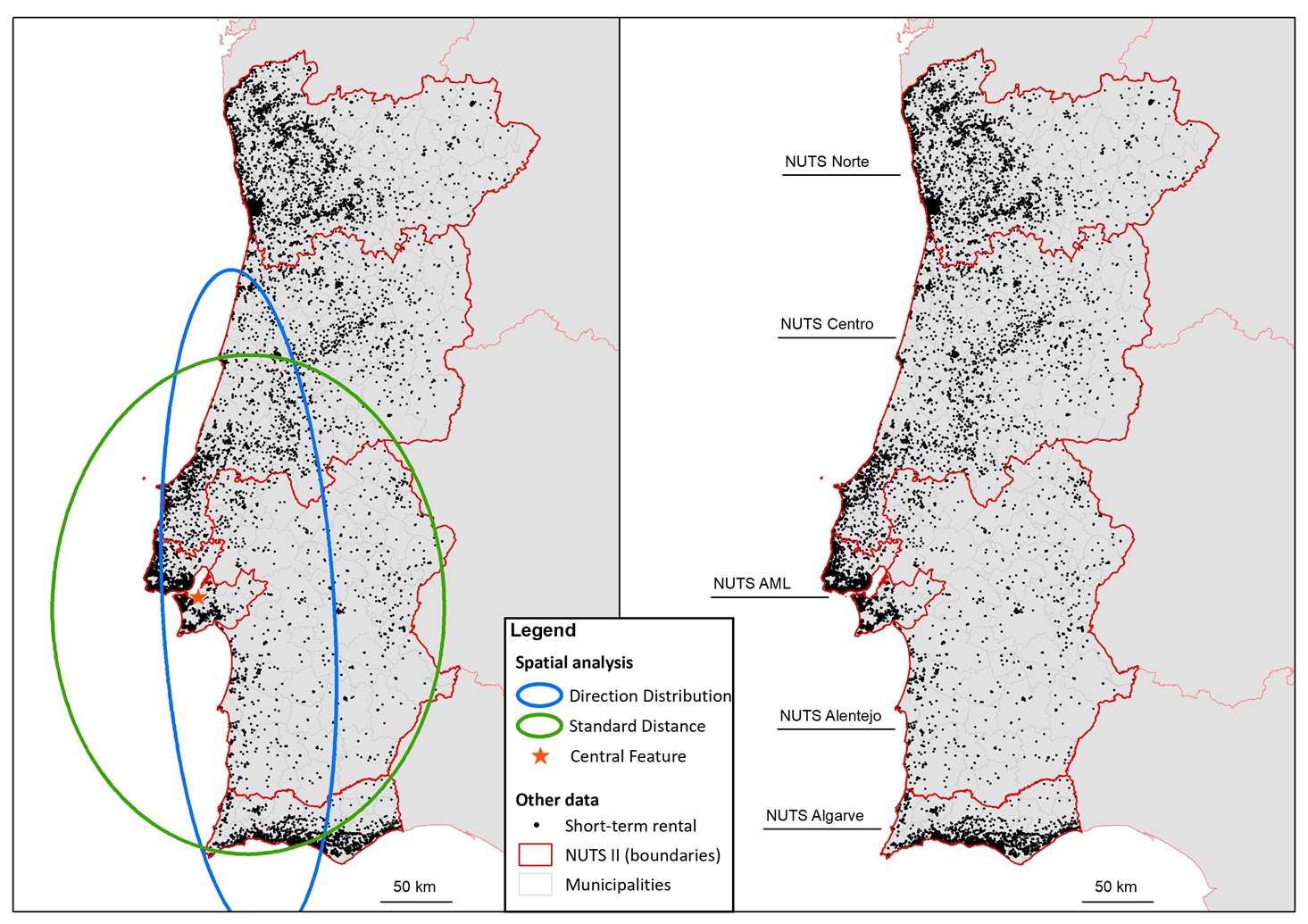

The spatial distribution and analysis operate using spatial measurement tools as the “mean center” (Figure 1), “standard distance” (Figure 1) and “ellipsis distance” (Figure 1), and (optimized) “hot spot analysis” (Figures 4 and5). On other hand,Figures 2 and3 are based on a statistical-spatial approach.

Mean center : determines the spatial position of the central point of a distribution, in X and Y. Such point is merely theoretical and its existence in the distribution is not required.

Standard distance : calculated to determine the probability of the spatial occurrence of points according to the calculated radius.

Where xi and yi are the coordinates for feature i represents the Mean Center for the features, and n is equal to the total numbers of features.

The Weight Standard Distance (SDw) extends to the following:

Where ωi is the weight at feature i and {X ̅,Y ̅}{X ̅ω,Y ̅ω} represents the weighted Mean Center.

Ellipsis standard : calculated to determine the general direction of the points’ distribution. The Standard Deviational Ellipse is given as:

Where xi and yi are the coordinates for feature i, {X ̅,Y ̅} represents the Mean Center for the features, and n is equal to the total numbers of features.

The angle of rotation is calculated as:

The standard deviations for x-axis and y-axis are:

Lastly, the density maps (Figures 4 and 5) aim to estimate the intensity of occurrence of a given specific phenomenon in a certain territory, giving the statistically significant hot and cold spots using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic. Using this method, it is possible generate a grid with values that translate the phenomenon’s intensity in each area unit.

Getis-Ord Gi* (Spatial Statistics), where xi is the attribute value for feature j, wi,j is the spatial weight between feature i and j, andn is equal to the total number of features.

3.2. Short-term rentals in Portugal

In the summer of 2019, there were 84,835 short-term rental units in Portugal with a capacity to accommodate 489,659 visitors.Table 1, which shows these units by NUTS II, makes it possible to draw the following conclusions: a) Algarve (39.5%) and Lisbon Metropolitan Area (29.3%) stand out as the statistical regions with the largest percentages of short-term rentals; b) Alentejo has just 3.2% of the national total; c) North (16.8%) and Centre (11.3%) are in an intermediate position in terms of short-term rentals.

This territorial analysis can be deepened. For example, the Lisbon Metropolitan Area is the second statistical region in terms of short-term rental units, but is the smallest region geographically, that is, its short-term rental units are closer together. By contrast, Alentejo has the lowest percentage of short-term rental units and is the largest region, that is, the spatial distribution of short-term rentals in this region is very dispersed when compared to other regions (Table 1 andFigure 1).

Figure 1 presents the spatial distribution of short-term rentals units in Portugal. The following points summarise the most important trends:

The distribution of short-term rental units is not uniform, with higher concentrations near the coast and lower numbers on the eastern border with Spain. This spatial distribution of short-term rentals can be empirically correlated with population density. In fact, there are more short-term rental units in the main Portuguese urban areas on the coastline, particularly around Lisbon, Porto, and in Algarve, and the interior of the country presents low numbers, with minor exceptions in places with more tourism activity and in medium and small urban conglomerations;

There is a significant and fairly even distribution in the Algarve region. This spatial distribution can be empirically related to a longstanding demand from tourists for second homes, with Portuguese and foreign visitors arriving in this region in the warmer months;

The short-term rental units that exist in Lisbon and Porto (and surrounding areas) are recent and result from the growth in urban tourism;

The above trends have not been inferred from mere observation ofFigure 1 (the scale may be misleading and hide thousands of overlapping points) but also from spatial statistics, namely the ‘standard distance’, ‘standard deviational ellipse’ and ‘central feature’ measures[8]:

The ‘standard distance’ measure makes it possible to perceive that the tendency for concentration of short-term rental units in Portugal is especially in the Centre and Algarve statistical regions;

The ‘standard deviational ellipse’ reinforces the idea of a tendency for centrality between the Centre and South of the country. Most importantly, the ellipse makes it possible to highlight the tendency for short-term rental units to be near the coast;

The ‘central feature’ point is located southeast of the municipality of Lisbon. This is the case because the municipality of Lisbon accounts for 22% of the national total of short-term rental units and the Lisbon Metropolitan Area 29%. It should be highlighted that the analysis of the 84,835 short-term rental units across Portugal indicates centrality precisely for the country’s capital.

3.3. Short-term rentals in the municipality of Lisbon

In July 2019, Lisbon had 18,661 short-term rental units with 106,721 bed-places [9].

Source: RNT and SIGTUR.

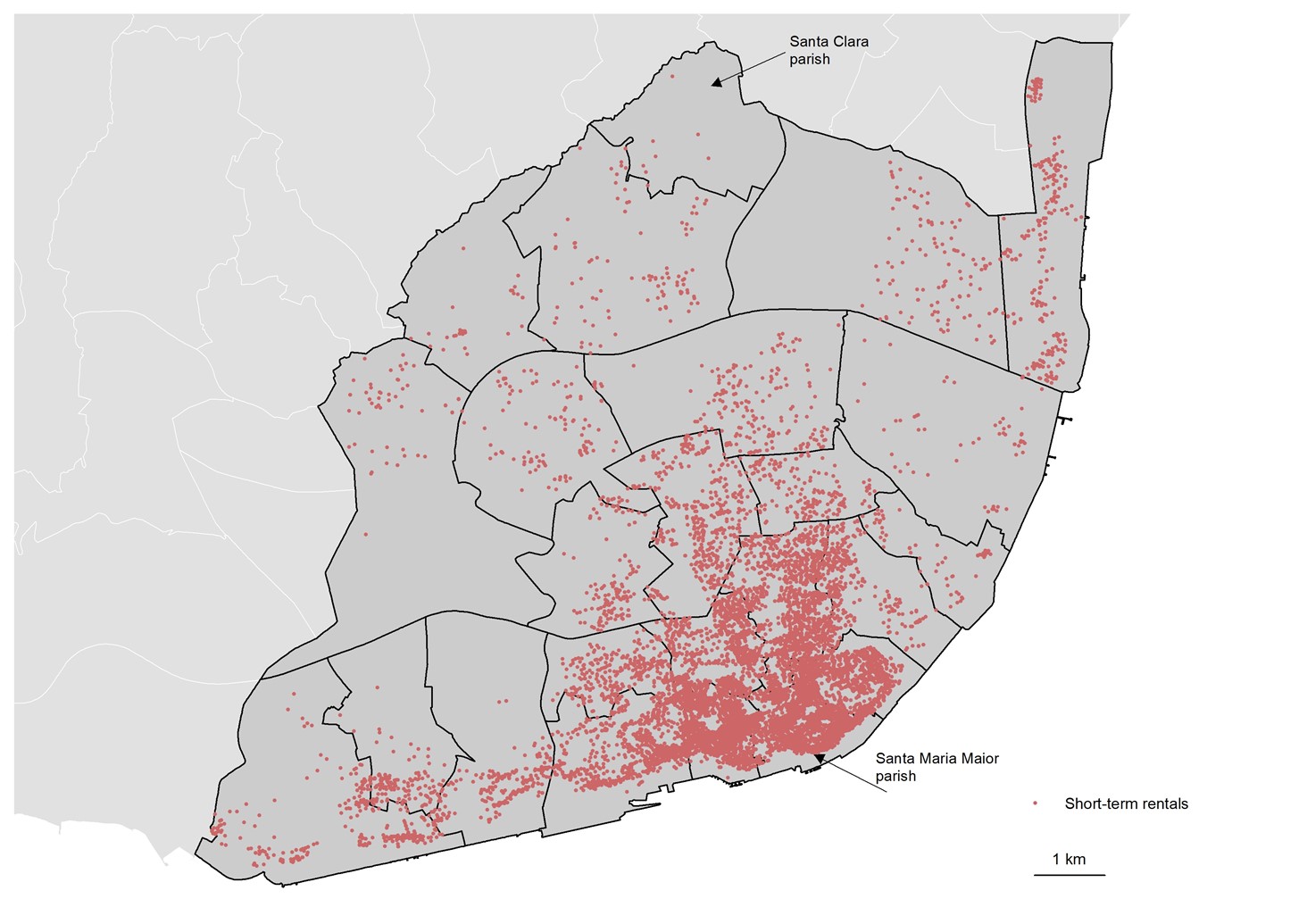

According toFigure 2, in the municipality of Lisbon short-term rentals are very concentrated in the city’s historic centre. By contrast, more peripheral areas, although they tend to have a higher population density, have fewer short-term rental units. For example, the parish of Santa Maria Maior (Lisbon’s most central, covering the downtown area) in 2019 had more than 4,500 short-term rental units, while the parish of Santa Clara (on the northern edge of the city) had fewer than 10.

Source: RNT and SIGTUR.

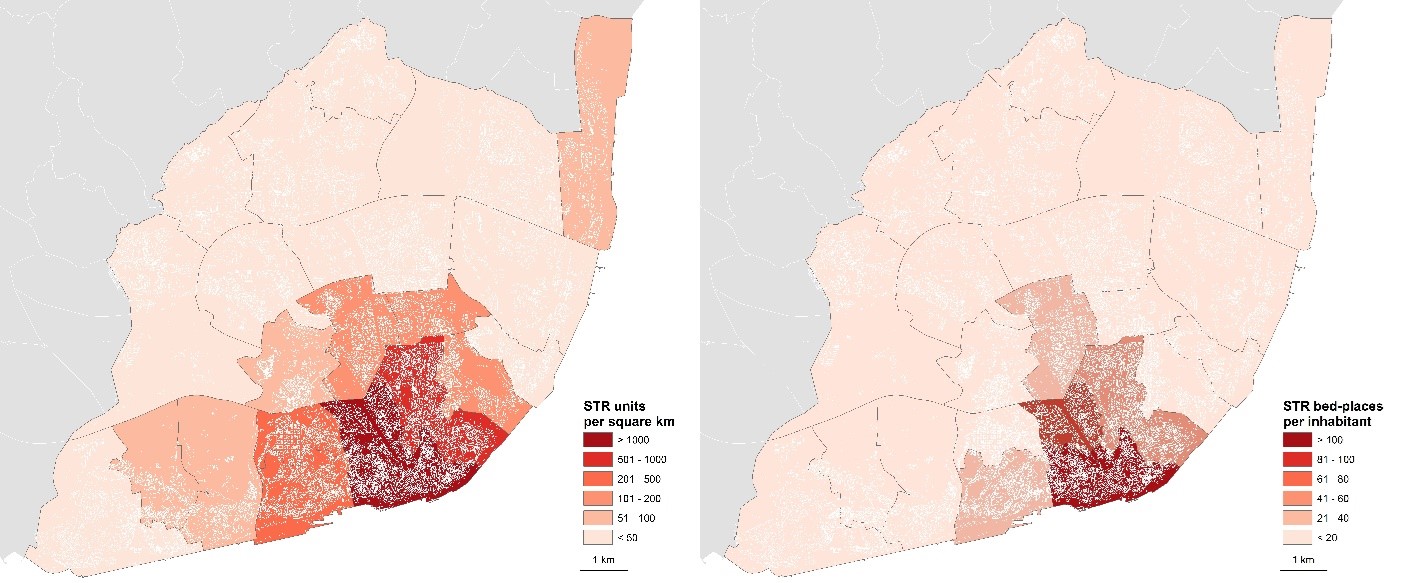

ObservingFigure 3, specifically the city centre, in the parishes of Santa Maria Maior and Misericórdia there are more than 1,000 short-term rental units per square kilometre, and more than 100 bed-places per 100 inhabitants (in fact, almost 200 bed-places per 100 inhabitants). In some peripheral parishes, as in the case of Santa Clara, the corresponding figures are near zero. This shows that short-term rental units are very much concentrated in the oldest parishes of Lisbon, not only based on their geographical position and on absolute numbers (Figure 2) but also on relative ones (Figure 3).

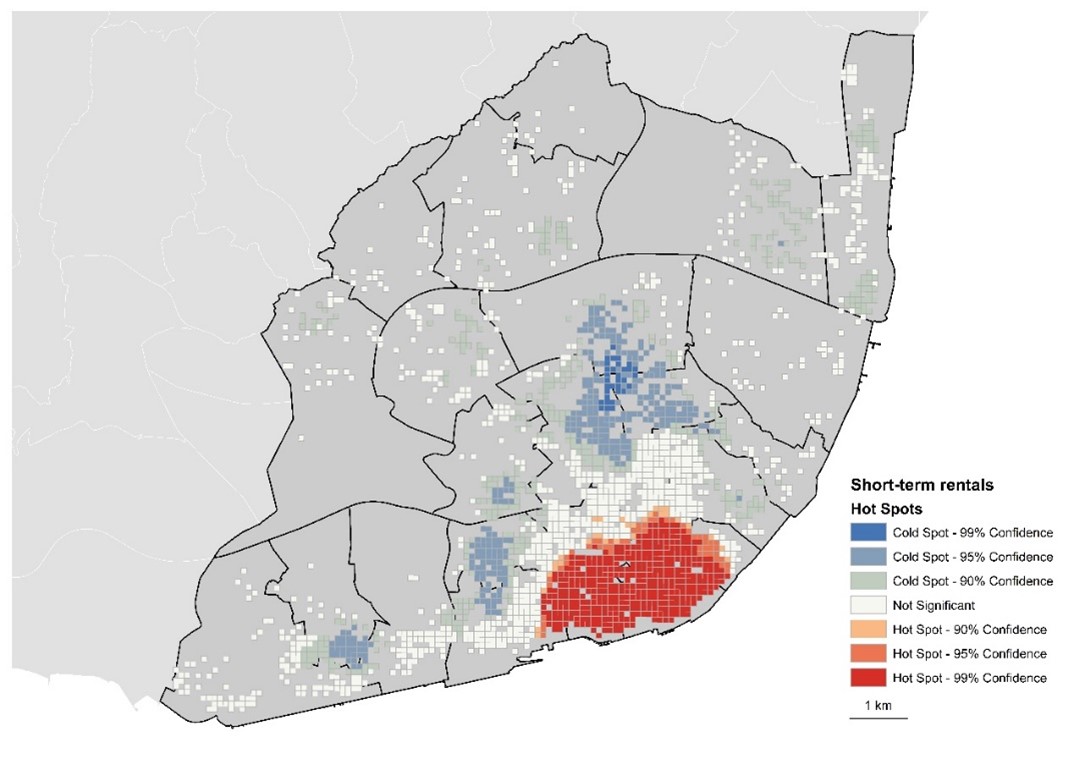

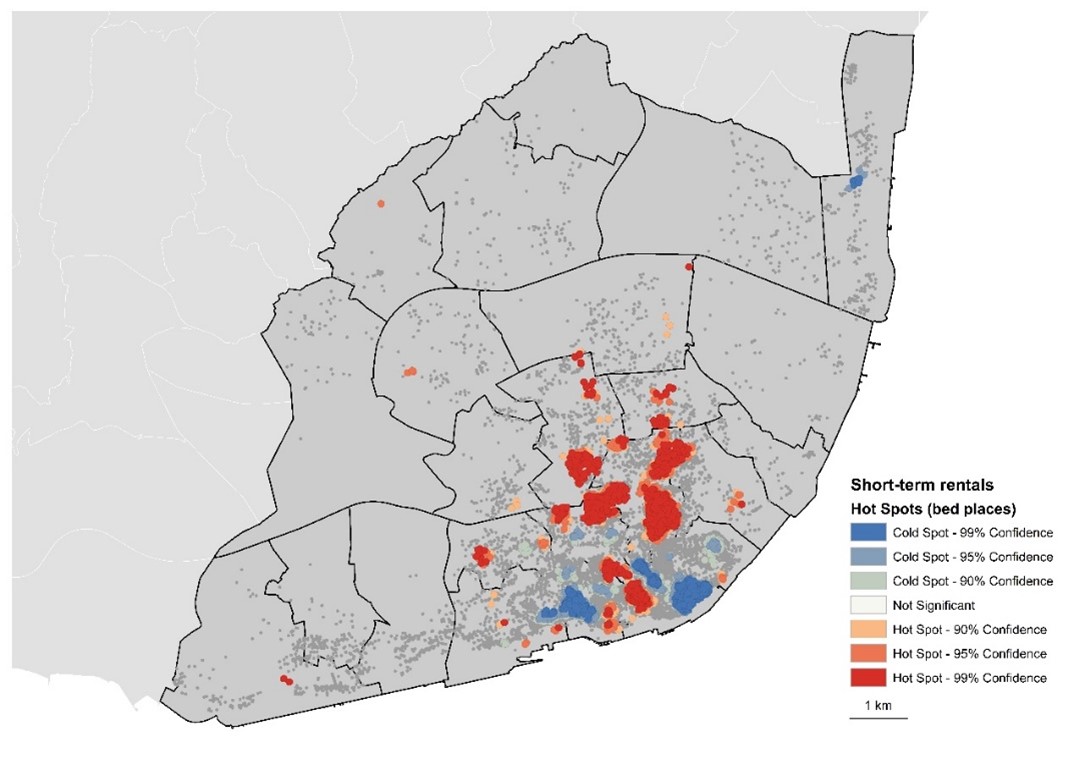

Following the spatial analysis,Figure 4 makes it possible to observe the tendency for clustering and the spatial patterns of short-term rental units in Lisbon. The majority of short-term rentals are downtown, in a tightly circumscribed geographical space. As shown inFigure 4, most short-term rental units are concentrated in the red area (hotspot area). Regarding this very circumscribed area, some results should be highlighted: a) the red zone contains more than 12,000 short-term rental units, which is 65% of the city’s total and 14% of the national total; b) the red area is 4 square kilometres and so has more than 3,000 short-term rental units per square kilometre; c) in these 4 square kilometres are located 14% of all short-term rental units in Portugal.

In the blue areas (cold spots) one can find various intermediate areas, in which there is still a significant concentration of short-term rentals; these areas correspond to more recent urban areas built in the first half of the 20th century. In the rest of the city, spatial statistics make it possible to identify areas of little significance, that is, where short-term rental units are very scattered, and areas in which this activity is absent.

Source: RNT and SIGTUR.

As can be seen inFigure 5, the concentration of establishments with a high number of bed-places is not exactly in the centre of the city, but rather in areas that are immediately adjacent to it. This relates to the average size of housing units, which are generally smaller in the historic centre. In this way, the higher numbers of bed-places are still in a central area, but in neighbourhoods built in the first half of the 20th century and not in the historic centre, where the housing stock is older.

4. THE SHORT-TERM RENTALS DEBATE

As pointed out in section 2, in the last decade the tourism in Portugal has grown extremely fast. It is to be noted that short-term rentals were a minor activity at the start of the 2010s, based on informal and seasonal models (Rio Fernandes et al. 2019a). This tourist activity was almost exclusively in the Algarve region, with the practice of second homes being rented out to tourists during the summer. In the decade that followed, short-term rentals spread across the whole country (Rio Fernandes et al. 2019a). Looking more closely at the municipality of Lisbon, in 2010 the number of short-term rental units there was around 3,000, with explosive growth to 18,661 units in mid-2019 (that is, growth of more than 500%).

4.1. Short-term rentals in the municipality of Lisbon

As analysed in section 3.2., the distribution of short-term rental units in Portugal is uneven. The spatial concentration of short-term rental units is predominantly near the coast, especially in the Algarve region. However, the most significant growth has been seen on the west coast, mainly in the Lisbon and Porto Metropolitan Areas, with the municipality of Lisbon alone having 22% of the national total.

Adamiak (2018) identifies the European cities with the highest number of Airbnb listings in 2017, showing Paris (56,800), London (55,400) and Rome (25,300) as the top 3. The city of Lisbon, which has 12,400 Airbnb listings, was very close of Amsterdam (12,500), Istanbul (12,900), Madrid (14,900) and Berlin (16,600). However, based on the number of Airbnb listings per 1,000 inhabitants, the Portuguese capital was in sixth position, behind Batumi, Split, Marbella, Venice, and Florence (Adamiak 2018). It is thus evident that the city of Lisbon stands out in the European context for the great significance of its short-term rentals, in both the absolute and relative approaches.

The boom in short-term rentals in Lisbon is thus one more case of a major European city that is having to cope with the excessive concentration of this activity (Adamiak 2018).It should be noted that the city of Lisbon until recently had no tradition of tourist accommodation aside from hotels (Rio Fernandes et al. 2019b). The figure of 18,661 short-term rental units in the municipality of Lisbon thus testifies to a violent social, economic, cultural and urban transformation that has occurred in a short space of time (mainly in the period 2014-2019).

This spatial-quantitative scenario analysed in section 3.2 demonstrates a functional imbalance that creates an unavoidable tension between residential and tourist functions (Mendes 2020). This tension is all the greater if one considers that the transformation has taken place in a very short period. It should be noted that a wider analysis of tourism in Lisbon would be necessary to take account also of the number of beds available in hotels, which are also concentrated in the city centre. These functional imbalances necessarily take our analysis to other concepts, such as the tourism carrying capacity (Barata-Salgueiro et al. 2017).

The rising profile of tourism in the Portuguese capital has not gone unnoticed by international players. According to the “Global Destination Cities Index 2019”, the city of Lisbon is among those that stand out in global terms where the growth of tourism is concerning (Mastercard 2019). The references to Lisbon in these international studies are relatively recent, in a trend that has become established only in the last decade, due to the rapid growth in urban tourism in the capital. The countless tourism awards attributed to Lisbon are another factor, to the extent that they reflect tourists’ preferences. It can be said that urban marketing policies and efforts to raise the profile of Lisbon as a city with a history and which is safe and has a good quality of life, have been successful. This economic model has been widely advocated by policymakers during and after economic crises (Seixas and Antunes 2019).

In parallel with the growth in the short-term rental business, interest in the city’s property stock has also increased on the part of international investors (Antunes and Seixas 2020;Gonçalves et al. 2020;Franco and Santos 2021). This phenomenon is cited in the annual study Emerging Trends in Real Estate: Europe 2020®, which places the Portuguese capital 10th among European cities in terms of its attractiveness for property investment, in part due to the projected returns on investment in the tourism business (ULI and PwC 2019). For its part, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development goes so far as to link the growth in tourism and the rise in housing prices, in stating that “the boom in the tourism sector and demand by non-residents (responding to government incentives tying visas to dwelling purchases) have been significant factors behind the strong growth in house prices in some locations” (OECD 2019, 21).

Inevitably, tourism creates externalities in destinations and is a catalyst of change, due to pressures generated from tourist flows and activities. As studies on tourism carrying capacity have shown, it is difficult (or even impossible) to define a specific number for how much is too much (O’Reilly 1986;Coccossis and Mexa 2004;McCool and Lime 2001;Zelenka and Kacetl 2014;Kennell 2014). Although tourism carrying capacity has been studied for several decades, a theoretical or practical consensus is still a long way off. The tourism carrying capacity concept is based on the idea that tourism development must be related to sustainability principles; otherwise, local systems can be affected and even the destination’s quality, competitiveness and attractiveness undermined. Tourism carrying capacity has presented various difficulties in terms of the quantitative measuring of overcapacity, although there are cases of practical use, especially in nature reserves, and some studies have also tried to apply the carrying capacity concept in urban areas, using a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches (Coccossis and Mexa 2004;McKinsey and WTTC 2017).

The measurement of carrying capacity is not only complex but must be adapted to each context (McCool and Lime 2001;Kennell 2014).Getz (1983) identifies six categories that must be especially taken into account, namely the ‘physical’, ‘economic’, ‘perceptual’, ‘social’, ‘ecological’, and ‘political’ dimensions. In the same way,McKinsey and WTTC (2017) identify some topics that are especially important to identify excessive tourist concentration, namely ‘alienated local residents’, ‘degraded tourist experience’, ‘overloaded infrastructure’, ‘damage to nature’ and ‘threats to culture and heritage’.

Looking at the case of Lisbon, it is possible to observe that most of these domains are undergoing transformation, if not saturation. For this reason, it is not surprising that a broad range of scientific studies has underscored the multidimensional negative impacts of short-term rentals in Portuguese urban areas, especially in the municipality of Lisbon. These studies highlight some major concerns about the intensification of tourism, such as gentrification, the financialisation of housing and touristification (Tulumello 2016;Antunes 2018,2019,2021;Cocola-Gant 2018;Ferreira and Antunes 2020;Mendes 2016,2018,2019;Lestegás 2019,Lestegás et al. 2019;Santos 2019;Sequera and Nofre 2020;Tulumello and Allegretti 2021;Van Heerden et al. 2020), the rapid rise in house prices and rents (OECD 2019;Antunes and Seixas 2020;Gonçalves et al. 2020;Franco and Santos 2021), the displacement of local shops (Barata-Salgueiro 2020), and urban tensions that are visible, for example, in the growth of social movements and activists (Seixas and Guterres 2020;Mendes 2020). These big topics – already widely studied by academics – overshadow other important concerns, such as the economy’s dependency on tourism sector (in terms of GDP and employment) or issues more familiar to the perception of locals, such as the tension between residential and tourist functions, the saturation and overloading of local infrastructure (e.g. public transport, public spaces) and negative feelings towards tourism.

All these negative externalities are more intense in the city centre, where, as shown in the analysis above, there are around 12,000 short-term rental units (14% of all short-term rentals in Portugal), circumscribed in 4 square kilometres in Lisbon’s older neighbourhoods. In this small and fragile area, the intensification of short-term rental is a new urban challenge with multidimensional impacts.

In the absence of an exact measure that could indicate how much is too much, it seems that there are overall, complex and multidimensional factors that could qualitatively point to this in urban areas. For example, a rapid increase in prices per square metre to buy and rent houses, growing difficulties in accessing affordable housing, signs of changes in the social fabric and the forced departure of local people, the saturation of local infrastructure, neighbourhoods becoming deserted at night, or the substitution of retail establishments serving the needs of local people by souvenir shops with global esthetical symbology.

To deal with these multiple negative externalities, Lisbon and Porto municipalities decided to create a tourist tax (to cover the annual investment on the requalification of the public space, to assure artistic and cultural dynamism and adequate urban services) (Borges et al. 2020), and more recently decided to suspend the licensing of new short-term rental units in the so-called ‘areas of contention’ (Antunes 2020;Pereira 2020).

To a degree, it can be said that the negative impacts cited here are not a consequence of the existence of short-term rental units, but of their excessive concentration in certain areas, coming close to monopolising the land use. However, this concentration is not in itself a clear indicator. For example, the Algarve is the region in Portugal with the most short-term rental units, but there is no debate about negative impacts from that activity (Rio Fernandes et al. 2019a). This means that the definition of the excessive concentration of short-term rental varies depending on the area and on the pre-existing multidimensional dynamics in the territory.

4.2. COVID-19: an opportunity for local people?

In a way that no one had foreseen, the boom in urban tourism was stopped in its tracks not by the pressure of social movements or political decisions, but by Nature, in the form of a global pandemic. Around the world, tourism has undergone a major contraction (Bhrammanachote and Sawangdee 2021). The short-term rental business, which had until very recently been a low-risk investment with rapid returns, is facing serious difficulties. In the case of Portugal, the country is among the European countries that are most vulnerable to the economic impacts of COVID-19, mainly due to the importance of the tourism sector for GDP and exports (UNWTO 2020).

Just what transformations will result from the pandemic has yet to be seen and calculated (Ferreira and Antunes 2020). However, from a political point of view, some answers are already forthcoming. The mayor of Lisbon, in an interview with The Guardian, said that:

“In a certain sense Covid has created an opportunity.… The virus didn’t ask us for permission to come in, but we have the ability to use this time to think and to see how we can move in a direction to correct things and put them on the right track.… There is that tension: too much of a thing [short-term rentals] is not good, but too little of it is a problem.… It’s a question of balance.” (The Guardian, 1 December 2020, Fernando Medina, mayor of Lisbon). Accessed on 5 December 2020 [10].

These statements from Fernando Medina are very pertinent, since they represent a recognition that the short-term rental business has created imbalances in the functioning of the city and that the pandemic is an opportunity to get it back “on the right track”[11]. In the same interview, the mayor also declared that:

“We need to make a shift. It should change the way the housing market works here in the city.… Having a house cannot be such a burden that you have to have two or three jobs – that’s not a dignified life for anyone.” (idem).

This series of statements by the mayor of Lisbon were made in the context of a new programme set up by the municipality named ‘Renda Segura’ (Secure Rent) that was launched in the early weeks of the epidemic. The programme’s objective is to transfer apartments used for short-term rentals over to long-term rentals, with landlords receiving rent at market rates, thanks to a monthly payment assured by the city council on top of the affordable rent paid by tenants[12] Despite the municipality’s efforts, by December 2020 just 177 owners had agreed to take part in the programme, with only 47 of these being former short-term rental units. This lack of participation is due to the expectation that the economic situation will soon return to normal and that the slump in revenue will be reversed in the short term (Pereira et al. 2021). To a certain degree, this measure is only of interest to short-term rental owners who were already thinking of withdrawing from this activity, due to the saturation that was being felt in the market. It should also be noted that owners’ expectation of a “return to normality” is not very different from the expectations of the population in general, who given the opportunity are also eager to see tourism rebound (Pereira et al. 2021).

The current moment is one of uncertainty. The short-term rental market will in future face two big challenges. On the one hand, recovering from the COVID-19 crisis and awaiting the return of normality, on the other, dealing with new policies to constrain and regulate the segment, as has already happened in many major cities in Europe and North America.

5. Concluding remarks: Lisbon and the international context of short-term rental

In many major cities, the discussion today is no longer about how much is too much, but rather about how to restore the balance of urban life (tourism and living, landscapes and urban real scenarios, national prices or inflated real estate profit margins). Similar developments have been seen in many cities in Europe and North America. The short-term rental market has driven the rapid transformation of leading urban destinations, prompting several major cities (e.g. Barcelona, Amsterdam and New York) to move to limit the spread of short-term rentals. The policymakers are making use of various models to constrain the activity, such as the suspension of new registrations and limits on the number of days that they may operate as such (Gurran and Phibbs 2017). It can be seen that even cities and regions that have historically received foreign tourists, such as the Balearic Islands (Spain), have moved to contain the short-term rental business, in large part because this activity affects the supply of housing and the property market in general, and so the lives of local people (Yrigoy 2019).

As happens in Lisbon, international studies that have analysed the social impacts of the short-term rental phenomenon have tended to link the excessive concentration of this activity with issues such as gentrification, housing financialization and touristification of places. As summarised byBecker (2013), short-term rentals make for happy consumers (who save money) and for happy homeowners (who make money), but for very unhappy neighborhoods.

This paper has analysed the spatial scenario of short-term rental units in the summer of 2019, that is, during its functional peak. It was in that scenario that several studies warned for disruptive effects of the excessive concentration of short-term rentals. These are complex and non-linear, such as the appropriation of cities for tourism, driving a substitution of the social fabric and a loss of identity in historic urban centres, gradually turning them into a huge monofunctional tourist resort, with few residents and a total void of cultural interest and authenticity. As several studies point out, it is not possible to define a magic number that indicates how much is too much. However, the spatial concentration identified in this study in the case of Lisbon, as well as the various scientific studies carried out over the last few years on the multidimensional repercussions of the intensification of short-term rental, all seem to converge in one direction.

Based on official numbers and using a geographical information system to specialize the phenomena, this paper highlights the spatial distribution of short-term rental units in Portugal and Lisbon, by showing their location and different gradients of concentration. This geographical approach is crucial to understand how to deal with these (sometimes) excessive numbers. Only by analyzing its spreading throughout space, it is possible to apply different levels of legislation that vary according to city parishes, areas, neighborhoods or even streets. This paper also highlights a different approach to the problem because seeing numbers on a map is much more real than looking them on a spreadsheet. This methodology also allows different scales of analysis. When focused on a particular street, results are sometimes even more alarming in terms of concentration. Of course, official databases could be outdated, and short-term rentals may even have closed (temporarily or permanently), continuing to be referenced on the database, but that´s a problem of all databases.

It seems unquestionable that the only way to achieve a balance between the positive and negative externalities without affecting the quality of urban life for those who live, work and use the city, is by having a clear scenario of what happened in the past to achieve better results for the future. In this sense, the work presented here, before the global pandemic crisis also shows the way to a needed practical framework adapted to different economic scenarios, some of them, no one could expect, but vital for future planning policies. At this moment, future works are already in progress showing a more a detailed analysis for some of Lisbon’ parishes and streets and taking into account population from 2021 Portuguese Census data.

During a global pandemic that has halted international tourism flows, it is now the right moment to reflect on what has been done in recent years and what kind of city we want for our future. Today, it is more unanimous that the local and regional economy needs the tourism industry, and that major European cities should have tourism, but that they should not be converted into mere tourist destinations. In the near future, it will be fundamental to ensure the sustainability of tourism and achieve a balance between its positive and negative externalities, so as not to undermine the quality of urban life for those who live, work and use their city for everyday activities.