Introduction

Ensuring safe, quality, and healthy food, reducing foodborne infectious diseases, and managing the burden of chronic disease in society are effective actions defined in the Resolution on the National Program on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Health 2015–2025 (2015). The basic areas of the resolution are ensuring the availability of food and promoting healthy food and products in cooperation with trained and qualified food industry stakeholders. Good hygiene practices (GHPs) mean good experience and habits related to work hygiene (e.g., hygiene of premises and workflow, personal hygiene) in a given industry. Application of the GHPs and good manufacturing practice (GMPs) principles is the basis for establishing the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system in the enterprise and thus the basis for ensuring safe food. The basic hygiene principles that condition the work in terms of GHPs are defined in the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the hygiene of foodstuffs (Regulation (EC) No. 852/2004, No. 1019/2008), which sets the objectives such as that food handlers are supervised and instructed and/or trained in food hygiene matters in accordance with their work activity, that those responsible for developing and maintaining the procedure or operating relevant guides receive adequate training in the application of HACCP principles, and that compliance with any requirements of national law concerning training programmes for persons working in certain food sectors is ensured. In 2021, the European Commission adopted Commission Regulation (EU) 2021/382, which amends an existing food safety regulation ((EC) No 852/2004) requiring food business operators to establish an appropriate food safety culture. Food safety culture concept is a general principle that improve food safety by increasing the awareness and improving the behaviour of employees in food establishments. Among others requirements employers shall ensure the appropriate training for employees. Training equips food handlers with the necessary knowledge and awareness of food safety principles, practices, and regulations. It helps them understand the potential risks associated with improper food handling and the consequences of foodborne illnesses. When food handlers are well-trained, they become more conscious of their actions and are motivated to follow proper food safety procedures consistently (Yiannas, 2023). The problem is that there are no minimum requirements for the providers and content of training and education. Research in the Slovenian area shows that fewer food business operators care about the training of their employees with the aim of reducing costs (Čebular et al., 2014). In practice, the abolition of vocational training requirements often leads to a situation where people come into contact with food without adequate formal training.

It should be emphasized that performing work according to the HACCP system and the principles of GHPs and GMPs are essential for the prevention of foodborne illness. To achieve this, adequate hygienic and technical conditions are required, as well as motivated, satisfied and qualified personnel. A person working with food must be treated in the same way as other risk factors (Jevšnik et al., 2008). One of the key elements in ensuring safe food is proper employee training. Effective training programs cover more than just the basics of microbiology and food hygiene. Programs are tailored to include various risk factors that employees encounter in their workplace. Training should have a positive impact on employee behaviour, reduce the risk of infection and/or food poisoning, improve product quality, and reduce complaints (De Sequeira et al., 2015). Numerous studies have been described in the literature in which employees' food hygiene knowledge was assessed using questionnaires (Pichler et al., 2014; Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018; Al-Kandari et al., 2019; Gruenfeldova, 2019; Taha et al., 2021). Studies have shown that employees with on-the-job training perform significantly better on GHPs knowledge than employees without training (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018; Taha et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to raise awareness and provide adequate training to employees, as this is the only way to achieve the necessary knowledge, skills, and appropriate attitudes (Seaman and Eves, 2010; Shinbaum et al., 2016; Ovca, 2020).

The aim of the study was to determine the knowledge of employees in the selected Slovenian food establishments about hygiene practices prior and after the conducted training. Thus, we aimed to determine the knowledge of selected content of GHPs, train employees in the area of selected content of GHPs and analyse the acquired knowledge of employees in selected food establishments. We hypothesized that the knowledge level of employees would increase after training and that employees who had previously attended one or more training sessions on GHPs would have more knowledge than employees without prior training.

Material and methods

Respondents in the selected food establishment: A total of 58 employees from the 11 food companies participated in the interview prior and after the training.

Survey: The survey included nine questions on general and sociodemographic characteristics of respondent (gender, age, educational level and direction, work experience) and twenty-eight questions divided into four sections: food contamination, personal hygiene and general hygiene principles, cleaning and disinfection, and the importance of training (Appendix A). Employees completed the survey an average of three days prior training, followed by training in GHPs, and then a re-survey after training. Training was conducted in small groups with an average of 4-6 respondents. Selected content of GHPs was presented using interactive materials (Power Point presentation, videos, animated films). Survey responses were scored and collected according to above mentioned four areas. A correct answer was scored one point, and an incorrect answer was scored zero point. A five-point Likert scale was used to measure attitudes toward the importance of employee training. The sum of the points achieved was the criterion for evaluating the respondents' knowledge.

Methods

Survey implementation: the purpose of the survey was to assess participants' knowledge of GHPs and to obtain their opinions on the impact of the training on their work. Knowledge level was determined as a percentage of correct responses by dividing the sum of points for correct responses by the number of points for all correct responses. Respondents were informed in advance that the survey was not intended to provide a general assessment of their knowledge, but to assess the impact of the training on their level of knowledge of GHPs.

Statistical analysis: the results obtained were processed and the basic statistical parameters (average and standard deviation) were calculated using the Microsoft Excel program (Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2019). To compare the results prior and after the training a paired t-test was used and to compare differences in demographic characteristics of respondents (educational level, work experience, previous participation of the respondents in the training) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used (SPSS Statistics, version 23). Means of experimental groups were compared using Duncan's test and paired t-test with 5% risk.

Results and discussion

Demographic characteristics of respondents

Overall, 25.9 % of men and 74.1 % of women participated in the survey (Appendix A). Of the respondents, 22.4 % had incomplete or completed elementary school, and 51.7 % completed lower or secondary vocational education (most frequently cooks, confectioners and waiters). This was followed by respondents with secondary professional or short-cycle higher vocational education (17.3 %) and respondents with university programs or master’s study programmes (8.6 %). A total of 25.8 % of respondents held the position of catering manager or kitchen manager, and 34.5% of respondents were employed as cooks. The remaining participants (37 %) were employed as assistant cooks or assistants. Of the respondents, 86.3% had at least 15 years of experience in the food industry.

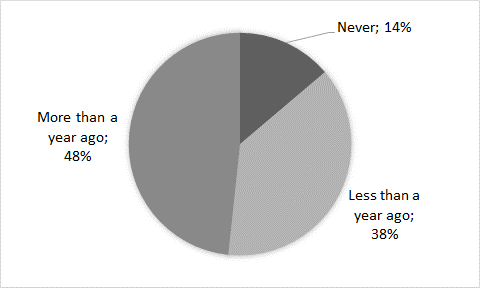

The results of our survey show that 86 % of respondents have attended training on GHPs in the past, while the rest of respondents (14 %) have never attended training (Figure 1). In comparison, 28 % of respondents in Ireland (Gruenfeldova et al., 2019) and 23% in Austria (Pichler et al., 2014) have never attended GHPs training.

Figure1 Share of respondents according to participation in education in the field of good hygiene practices

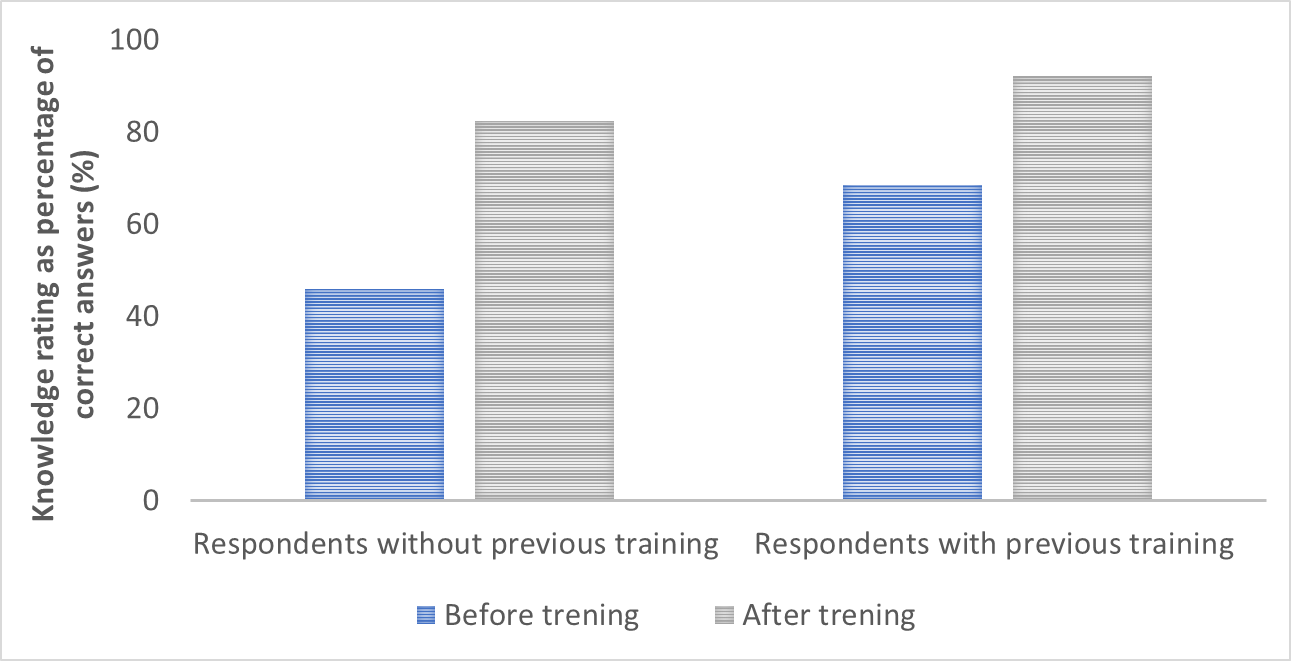

Respondents' knowledge of GHPs prior our training had a significant effect on the results; those who had already attended food hygiene training had a significantly better (P ≤ 0.001) survey result (68.4%) than respondents who had never attended training (45.9 %). Knowledge acquired at the last training also improved significantly for both groups of respondents (P ≤ 0.001; 92 % vs. 82 %) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Assessment of respondents' knowledge of GHPs based on their participation in training in the past

In the study by Sanlïer et al. (2020), participants were divided into three groups: a group with long-term training (184 hours of training), a group with short-term training (eight hours of training), and a control group with no food hygiene training. The knowledge test was administered prior training, after training, and 12 months after the training. The knowledge test after one year showed an exceptional effect of the long-term training, which affected not only the increase in knowledge, but also the positive attitude and implementation of GHPs among the food handlers. Their knowledge became permanent.

The gender of the participants did not affect the level of knowledge, which is to be expected since men and women work in the same work environment, while a significant relationship between work experience and knowledge of GHPs was demonstrated (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018). In our study, there was a significant difference in the level of knowledge after the last training, as men had a mean score of 70.4 % and women 63.4 % (t value = -2.075, P = 0.044). In this context, it should be noted that the percentage of male respondents was significantly lower than that of female respondents. The higher knowledge level of males was also related to their educational level, as 86.7 % of respondents had at least a secondary vocational education, while this percentage was lower for female respondents (74.4 %). Comparable studies show the same, as respondents with at least a high school degree performed better than respondents with an elementary school degree (Al-Kandari et al., 2019; Taha et al., 2021).

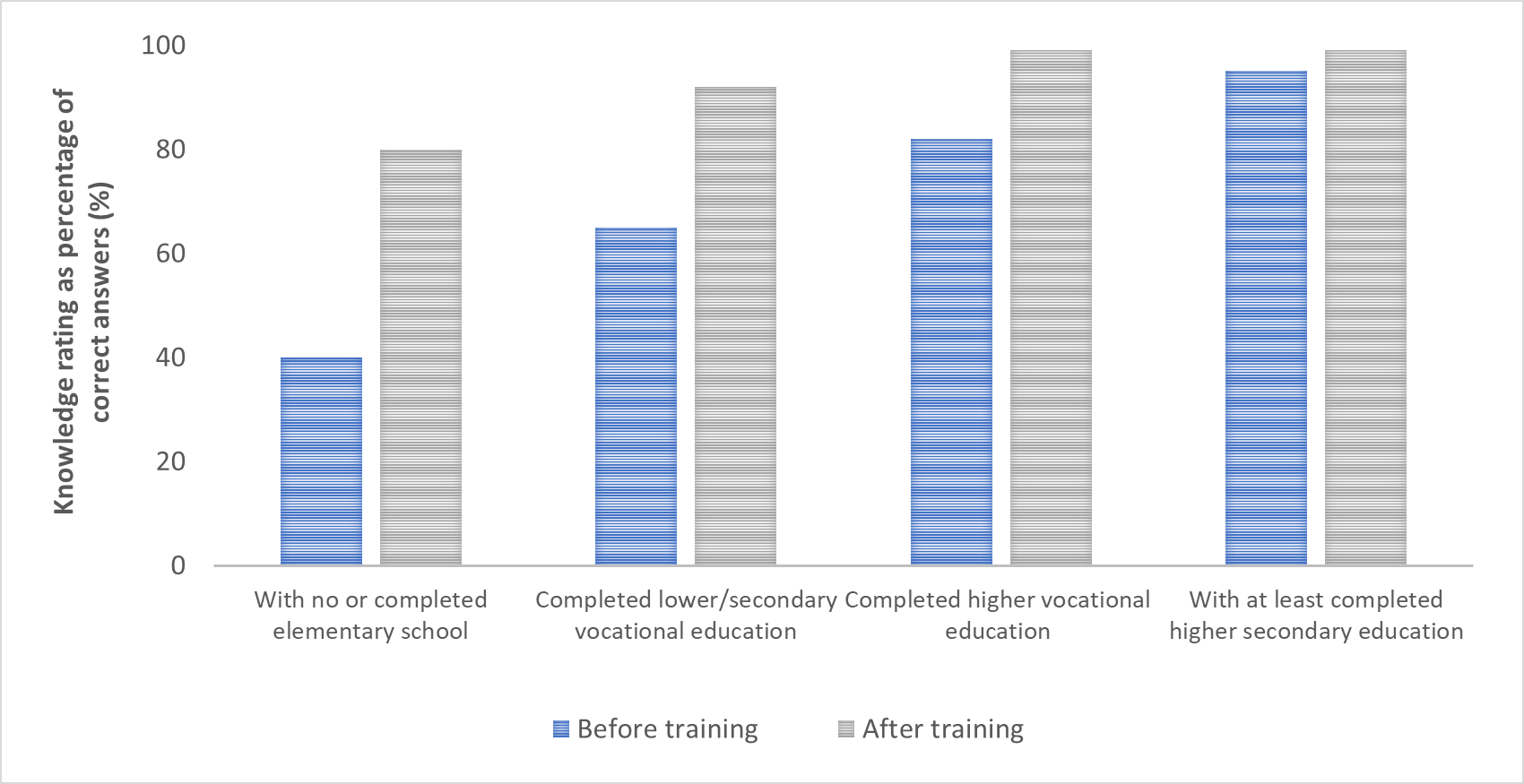

Respondents' age had a significant effect on their knowledge (P ≤ 0.001) as well as other factors (e.g., education or experience), independent on food hygiene training. Respondents under 40 years of age achieved a knowledge level of 57 %. Among them, 21 % of respondents had at least a secondary vocational degree. Among respondents aged 41 years and older, 27 % had at least a secondary vocational degree, and they achieved a knowledge level of 68 %. Secondly, work experience had a significant effect on knowledge scores (P ≤ 0.001). Respondents with nine years of professional experience in the food industry scored the lowest (35 %), while respondents with more than 15 years of professional experience in the food industry scored the highest (65-69 %) (not presented in tables of figures). As mentioned earlier, the respondents' level of knowledge was also significantly (P ≤ 0.001) influenced by their level of education (Figure 3). The lowest level of knowledge prior the implementation of the training was achieved by respondents with no or completed elementary school and participants with completed lower/secondary vocational education (40-65 %). A better result was achieved by participants with completed higher vocational education (82 %), and the highest level of knowledge was achieved by participants with at least completed higher secondary education (95 %).

In the study by Ambrožič et al. (2016), it was found that employees with completed vocational education had a higher level of knowledge in food hygiene than employees without formal education. This was also confirmed by the study of Darko et al. (2015), participants with acquired formal education had more knowledge and were better trained. Thus, there is a strong correlation between food hygiene knowledge and employee hygiene habits.

Figure 3 Assessment of respondents' knowledge of GHPs according to their level of formal education

Survey responses

The correct answers of 58 respondents are given as a percentage of the correct answers. Prior training, the number of correct answers ranged from a minimum of 6.9 % to a maximum of 100 %. In the first phase of this study, the mean knowledge level was 65.3 %; after training, the knowledge level was significantly higher (P ≤ 0.001) and was 91.0 % (Table 1). The percentage of correct answers increased from a minimum of 72.4 % to a maximum of 100 % after training.

Table 1 The average rating of respondents' knowledge in each group of GHPs questions

Scores with a different superscript letter ( a-b) are statistically significantly different (P ≤ 0.05)

In general, the results showed that workers have poor knowledge about GHPs. Regular training of food workers on GHPs could have a significant impact on improving food hygiene and, together with other activities and measures, could lead to improved food safety (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018) and food safety culture (Yiannas, 2023).

Food contamination

Seven survey questions addressed knowledge of food contamination (Appendix A, Section 2). The results show that the average respondent's level of knowledge about contamination possibilities was 49.5 %. Many respondents (77.6 %) knew that food can be contaminated with microorganisms by other food. On the other hand, only 15.5 % of respondents correctly believed that normal appearance, smell and taste do not mean that the food is safe, which is comparable to the survey in Montenegro, where only 18 % of respondents correctly answered the same question (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018). Even 65.5 % of respondents answered incorrectly to the question that they can wear jewellery when working with food, but must be careful to do so consistently when washing their hands, while the percentage of correct answers is even lower when claiming that wearing jewellery has no effect on food contamination (43.1 %). Hand sweat, dirt, food debris and microorganisms collect under jewellery and watches. Bracelets with jewellery and watches can never be washed properly, so they should not be worn when handling food (NIJZ, 2014). More than half of the respondents (53.4 %) did not know that kitchen towels can be a source of cross-contamination, while the percentage of incorrect answers in the survey in Montenegro was significantly higher (78.1 %) (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018).

Education on personal hygiene and general hygiene rules

Respondents scored highest on questions about personal hygiene and general hygiene rules. The average knowledge level prior training was 76.4 % and after training 93.0 %. 92.5 % of respondents correctly answered the question about basic hand washing resources (Appendix A, Question 20). Similarly, 83.7 % of respondents correctly answered the question about what we use to dry our hands (Appendix A, Question 21). Respondents knew that they should not handle raw foods if they have indigestion, even if they are later thermally treated (84.5 %). The worst result was obtained when asked about wearing and storing work and personal clothing (39.7 %) (Appendix A, Question 17). In addition, only 53.4 % of respondents answered correctly that chewing is not allowed in the workplace in the food industry. The percentage of correct responses increased significantly after training (93.1%).

A higher assessment of knowledge level was expected after the training. The percentage of correct answers ranged from 84.5 % to 100 %, and the average knowledge level after training was 93.0 %.

People who are carriers of infectious disease agents are not allowed to work in the production and distribution of food because they could directly or indirectly endanger the health of consumers through food (Article 5 of Act on the health suitability of food and products and substances that come into contact with food (ZZUZIS), 2000). Therefore, food workers have a great moral and legal obligation to know and consistently follow and implement the basics of hygienic procedures in food preparation. One of the factors in ensuring safe food is also the respect to personal hygiene, which prevents the outbreak of food- and waterborne diseases (NIJZ, 2014). Food hygiene studies (Djekic et al., 2020) have shown that personal hygiene is a prerequisite for preventing the transmission of foodborne illness. Consumers rated food hygiene as a key factor in ensuring safe food.

Education about cleaning and disinfection

Seven questions were related to knowledge about cleaning and disinfection (Appendix A, Section 4). The results show that the average knowledge level of the respondents was 56.1 % prior the training and 89.4 % after the training. Respondents scored the highest score (64.8 %) on statements about the cleaning schedule. Most respondents knew that the cleaning schedule included information about what to clean (91.4 %), when to clean (86.2 %), and who does the cleaning (87.9 %). A much smaller percentage of respondents correctly answered that the cleaning plan does not include guidance on the most common cleaning errors (27.6 %) and applicable GHPs legislation (31.0 %).

After the training, the percentage of correct answers for the cleaning plan questions increased to 89.7 %. On the other hand, only 24.1 % of the respondents believed that a surface without visible food debris and aesthetically sound did not mean that it was clean. The percentage of correct answers increased to 82.8 % after the training. A relatively small percentage of respondents knew the difference between cleaning and disinfection (55.2 %). Compared to other surveys, they achieved the lowest result, as, for example, 71.1 % of participants in Montenegro knew that cleaning and disinfection are not the same procedure (Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018), while this percentage was significantly higher in the Austrian survey (94 %) (Pichler et al., 2014). When asked about the storage of cleaning products and food (Appendix A, question 25), respondents showed less knowledge, as only 51.7 % of respondents knew that properly labelled cleaning products may only be stored in the same room where food is prepared if they have a special place and are only used for intermediate cleaning. Only 6.9 % of respondents answered correctly to the statement that we use cleaning concentrates for on-site cleaning, making this statement the worst result of the questionnaire. After the training, the percentage of correct answers increased significantly (79.3 %). When diluting cleaning agents, we must always follow the instructions for use, because even a minimal deviation in the ratio can damage surfaces or the user (Confidenti et al., 2020). Due to lack of personnel, insufficient knowledge in the field of cleaning, unsuitable cleaning agents and cleaning accessories, errors in the cleaning process can also occur (e.g. mixing of agents with each other, use of too high or too low concentration of cleaning agents, use of soiled cloths) (Confidenti et al., 2020).

Respondents' opinions on the need for education on good hygiene practices

After the training, respondents' opinions about the need for ongoing training in GHPs changed, as the sense of burden from repeated participation in the training decreased, while the percentage of people who found the training useful in their work increased.

People who come into contact with food in their work have long been recognized as an important risk factor in providing safe food (Ovca, 2020).

Conclusions

The study has some limitations. Because of the small sample - 58 respondents - we cannot generalize the results. The study did not include the same number of participants by gender, which could affect the results obtained.

When interpreting the results, it should be considered that in the survey we measured the level of knowledge (percentage of correct answers in the questionnaire) of respondents who handle food in their work and are employed in catering or commercial food establishments, but not their actual handling of food, since we did not observe and evaluate respondents at work. Worker performance is largely determined by knowledge, but the work environment also has a significant impact on individual behaviour. This includes both the physical environment (e.g., room layout, availability of work equipment) and the influence of organizational culture on individual work organization (e.g., available time and personnel, supervisor attitudes, compliance with GHPs regulations).

If one would like to examine the acquired knowledge in more detail, it would also be necessary to examine it after a longer period of time (e.g., six months) and measure the long-term effects on knowledge and possible changes in employee attitudes and behaviour. It would also be possible to monitor the effects of employees' participation in short-term and long-term training, and the knowledge acquired would be reviewed over a longer period of time.

The study could be expanded to include an additional research model, such as interviewing respondents and observing employees at work. Similar studies (Pichler et al., 2014; Barjaktarović-Labović et al., 2018; Al-Kandari et al., 2019; Taha et al., 2020, Rifat et al., 2022) examined different approaches in education and training to improve knowledge, attitudes, and food handling. Most studies used a group and measured changes prior and after training. Some studies measured also attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, behaviour, inspection results, or results of microbiological analysis. Studies addressed multiple domains, usually food safety and food hygiene and the subdomains of food cross-contamination and personal hygiene.

Acknowledgment: This manuscript is part of BSc thesis named Analysis of knowledge of hygiene practices in food plant, issued by Suzana Radinović. This study was partly supported financially by the Slovenian Research Agency (grant no. P4-0234 and P4-0116).

References

Act on the health suitability of food and products and substances that come into contact with food (ZZUZIS) (Zakon o zdravstveni ustreznosti živil in izdelkov ter snovi, ki prihajajo v stik z živili (ZZUZIS)). 2000. Official Journal of Republic Slovenia 10 (52): 6949–6954

Appendix A: A survey on knowledge of good hygiene practice with response rates of 58 respondents before and after the training