INTRODUCTION

Hotel frontline employees perform a critical role in directly engaging with customers. Customers’ perception toward the hotel is primarily established during the service encounter (Buil, Martinez and Matute 2016;Karatepe et al. 2006;Wang and Wong 2011;Wieseke et al. 2007;Yang 2010). Studies have showed that unsatisfying service encounters result from frontline employees failing to deliver quality service and satisfying customer demands (Bitner, Booms and Tetreault 1990;Cho and Johanson 2008;Lages et al. 2016;Lam, Lo and Chan 2002;Xu, Martinez, Hoof, Duran, Perez and Gavilanes 2018). To overcome this challenge, hotel firms are recommended to develop frontline employees’ commitment and encourage employees to perform extra-job duties(Karatepe and Magaji 2008;Kusluvan et al. 2010;Nadiri and Tanova 2010;Yang 2008).

Extant literature has argued that employees committed to their organizations are productive, responsible and good job performers (Garg and Dhar 2014;Organ and Ryan 1995;Yao, Qiu and Wei 2019). They tend to demonstrate service-oriented attitudes and behaviors (Kusluvan et al. 2010). Employees who are good organizational citizens respond rapidly to customer demands, avoid customer complaints, increase customer retention and deliver quality service (Ma and Qu 2011;Raub 2008;Yoon and Suh 2003). Given the known influence on subsequent successful delivery of quality service, examinations of the factors that contribute to organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) continue to be of great interest to tourism researchers and practitioners (Chiang and Birtch 2011;Lam et al. 2002;Lee, Magnini and Kim 2011;Namasivayam and Zhao 2007;Wang and Wong 2011;Yoon and Suh 2003). However, most extant studies have been conducted in the context of the workplace, while little tourism research has explored the linkage of tourism involvement to work attitude and behavior.

Exploring the influence of tourism involvement on work attitude and behavior is reasonable because tourism has effects on tourists’ overall or work lives (Chen, Huang and Petrick 2016;Neal, Uysal and Sirgy 2007;Sirgy et al. 2011;Yeh 2013). The nature of work needs continuous resources and efforts to complete tasks, which results in psychological and physiological fatigue (Rook and Zijlstra 2006). Studies have suggested that tourism contributes to work recovery and in turn positively influences tourists’ work lives (Chen et al. 2016;Etzion 2003;Neal et al. 2007;Sirgy et al. 2011;Syrek et al. 2018). According toGilbert and Abdullah (2004), people who practice more tourism are more satisfied with their work lives than those who undertake fewer tourism activities. Therefore, it seems fair to consider that people with different degrees of tourism involvement may display different work outcomes. Moreover, researchers have identified the correlates of organizational commitment (Kusluvan et al. 2010;Vandenabeele 2009;Yousef 2000) but it is unknown whether the association between tourism involvement and OCBs can be mediated by organizational commitment.

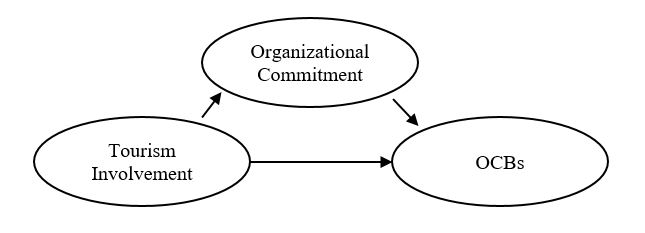

Therefore, main purposes of the current study are 1) to extend existing tourism knowledge in the hotel industry by examining the influence of tourism involvement on organizational commitment 2) to study the effects of organizational commitment on OCBs 3) to investigate the effect of tourism involvement on OCBs and 4) to probe the mediating role of organizational commitment in the relationship between tourism involvement and OCBs. The conceptual model is shown inFigure 1. Recovery theory is used as a framework to explain the association between tourism involvement, organizational commitment and OCBs, since it emphasizes the importance of recovery during non-working time to consequent work performance (Hobfoll 1998).

The current study makes several theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, this study investigates the interrelationship between tourism involvement, organizational commitment and OCBs in the hotel industry. There are limited tourism studies exploring this issue and therefore the outcomes of the current study can contribute to the tourism literature on involvement and human resource management. From a practical view, as mentioned above, hotel managers are striving to promote frontline employees’ organizational commitment and OCBs. If the effect of tourism involvement on work attitude and behavior is supported by current study, it provides hotel managers with practical insights into factors that can enhance organizational commitment and OCBs.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

1.1. Tourism involvement

The concept of involvement was first introduced bySherif and Cantril (1947). Since then, marketing scholars have extensively used the concept of involvement to examine consumer behavior. A general accepted notion of involvement is a self-concept that links individuals’ values with an object or activity (Sherif and Cantril 1947;Yeh 2013). In other words, involvement is an individuals’ recognized relevance of an object according to values and interests (Zaichkowsky 1985). When people are involved with an object, this involvement can influence their attitudes and behaviors associated with it (Slama and Tashchian 1985;Yeh 2013).Havitz and Dimanche (1990:184) defined tourism involvement as “a psychological state of motivation, arousal or interest between an individual and recreational activities, tourist destinations or related equipment, at one point in time, characterized by the perception of the following elements: importance, pleasure value, sign value, risk probability and risk consequences”. They further argued that tourism involvement can influence tourists’ searching, evaluating and participating behavior.

In the tourism sector, researchers have investigated tourism involvement from a variety of perspectives. For example, some studies applied the concept of tourism involvement to classify tourists (Cai, Feng and Breiter, 2004;Caruana et al. 2014;Gursoy and Gavcar 2003), decision makers (Atadil et al. 2018), casino gamblers (Park et al. 2002) and tourism shoppers (e.g.Hu and Yu 2007;Kinley, Josiam and Lockett 2010). A stream of studies inspected how tourism involvement is related to different tourism issues, such as travel decision-making (Clements and Josiam 1995;Zalatan 1998), place attachment (Gross and Brown 2006;Jiang, Wu and Lu 2014), opinion leadership (Jamrozy, Backman and Backman 1996), bird-watching trips (Kim, Scott, and Crompton 1997), dark tourism (Wang, Chen and Xu 2017), travel information search behaviors (Park and Kim 2010), travel purchasing behaviors (Huang, Chou and Lin 2010), wine tourism (Alonso et,al. 2015) and sustainable tourism (Stumpf and Swanger 2015). Several studies have identified that, with different levels of tourism involvement, tourists demonstrate different psychological status and behaviors during and after tourism activities (Jamrozy et al. 1996;Hwang, Lee and Chen 2005;Park and Kim 2010).

Much extant research on the influence of tourism involvement is conducted from a non-work perspective, since tourism activities and work have been long regarded as two opposite activities. Few studies have attempted to examine the linkage of tourism activity to people’s work outcomes (e.g.,Chen et al. 2016;Westman and Etzion 2001;Yeh 2013). Among them, taking vacations was found to reduce work strain and burnout (Chen et al. 2016;Chen, Petrick and Shahvali 2016;Westman and Etzion 2001). One study found that tourism involvement contributes to job satisfaction and work engagement of frontline hotel employees (Yeh 2013). The above studies have indicated that people’s tourism experiences can influence their work-related outcomes. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that tourism involvement may be related to both organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior.

1.2. Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment is an attitude related to job outcomes that has gained extensive research attention in human resource management studies. Many scholars have attempted to define organizational commitment. For example,Mowday and his colleagues (1979) argued that commitment is related to an individual’s attitude toward his/her organization. Therefore, they emphasized attitudinal commitment.Morris and Sherman (1981) suggested that commitment is the balance between inputs and outcomes. If an employee receives more from the organization than s/he invests or contributes, organization commitment emerges.McGee and Ford (1987) argued that continuous commitment is based on employment alternatives and personal sacrifice.

One of the most widely recognized definitions was put forth byMeyer and Allen (1991). From their point of view, organization commitment is a multidimensional concept. Three dimensions—affective, continuance and normative—are included. Affective commitment refers to employees´ emotional attachment to the organization. When employees’ expectation matches self-fulfillment and accomplishment in their organization, they tend to have stronger affective attachment. With strong affective attachment, employees tend to perform for the organizations’ interests and feel a sense of organizational commitment. Continuous commitment is employees’ perceived cost of leaving their organization. It results from potential losses in employee time and effort if they leave the organization. When employees have a high perception of increasing sunk costs in their organization, they become committed. Normative commitment refers to employees’ perceived obligation of staying in their organization, or in other words, employee loyalty to an organization (Meyer, Allen and Smith 1993).

An extensive review on tourism human resource management (HRM) conducted byKusluvan et al. (2010) identifies various factors contributing to organizational commitment, such as compensation, work conditions, career development, job satisfaction, HRM practices, the job itself, group cohesiveness and communication with coworkers.In the hotel sector, the issue of organizational commitment has been widely examined by researchers. Some studies have explored the antecedents of organizational commitment, such as job satisfaction (Gunlu, Aksarayli and Percin 2010;Yang 2010;Yao et al. 2019), person-organization and person-job fits (Iplik, Kilic and Yalcin 2011), reward climate (Chiang and Birtch 2011), procedural justice and transformational leadership (Luo, Marnburg and Law 2017) and employee trust (Yao et al. 2019). Some studies examined the impact of organizational commitment (e.g.Demir 2011;Garg and Dhar 2014;Kuruüzüm, Çetin and Irmak 2009;Yao et al. 2019). For example, organizational commitment was found to contribute to job satisfaction (Kuruüzüm et al. 2009), service quality (Garg and Dhar 2014), and employees’ attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (Yao et al. 2019).

The abovementioned literature shows that organizational commitment has been widely investigated in the hotel sector. However, little research has attempted to explore how organizational commitment is related to the non-work domain and organizational citizenship behavior. By examining the interrelationships among these variables, knowledge of both antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment can be enriched.

1.3. Organizational citizenship behavior

Employees’ OCBs are extra-role behaviors beyond the formal job requirement. An organization can generally gain benefits from OCBs (Brief and Motowidlo 1986;Nadiri and Tanova 2010;Organ 1988). OCBs are defined byOrgan (1988:4) as “individual behavior that is discretionary not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization”. OCBs are positive attitude and behaviors. Good organizational citizens tend to help other members and the organization itself (Lee et al. 2011). They exert extra effort in their organizations, such as volunteering for extra jobs, helping coworkers, working long days and making suggestions for improvement (Stamper and Van Dyne 2003;Testa 2009;Yen and Niehoff 2004;Yoon and Suh 2003). However, organizations have difficulties encouraging their occurrence and punishing their absence, since OCBs are voluntary behaviors (Moorman and Blakely 1995).

One of the most popular OCB models was proposed byOrgan (1988). Organ argues that OCBs have five dimensions, namely altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, civic virtue and conscientiousness. Altruism means employees are willing to help other members to conduct organizational tasks; courtesy is the respect to others; sportsmanship is related to employees’ positive attitudes and behaviors toward inconveniences; civic virtue refers to employees getting responsively involved in the political life of their organization and giving constructive advice; conscientiousness is the discretionary behavior that occurs when employees perform beyond their job requirements.

Given that OCBs benefit an organization, drivers of OCBs have been extensively investigated in the general management domain (e.g.,Bateman and Organ 1983;Eby et al. 2015; Farh, Podsakoff and Organ 1990;Kataria, Garg and Rastogi 2013;Kiffin-Petersen, Jordan and Soutar 2011;Mackenzie, Podsakoff and Paine 2000;Mackey et al. 2018;Netemeyer et al. 1997;Podsakoff, Ahearne and Mackenzie 1997).Podsakoff, Mackensie, Paine and Bachrach (2000) have demonstrated four antecedents of OCBs: employee variables (e.g., job satisfaction, fairness perception), task characteristics (e.g., task feedback, task routinization), organizational characteristics (e.g., organizational formalization, organizational inflexibility) and leadership behaviors (e.g., supportive leader behavior, leader role clarification).

The issue of OCBs has also attracted much research attention in the tourism sector. Some studies were conducted in the restaurant sector (e.g.,Cho and Johanson 2008;Stamper and Van Dyne 2003;Walz and Niehoff 2000). For example, organizational commitment (Cho and Johanson 2008), work status, work-status preferences and organizational culture (Stamper and Van Dyne 2003) were found to have effects on OCBs. OCBs can reduce food cost and customer complaints while increasing perceived company quality, operating efficiency and customer satisfaction (Walz and Niehoff 2000). In addition to the restaurant sector, OCBs were considered to be positively related to organizational culture and leader-member exchange relations in cruise lines (Testa 2009). Job satisfaction, trust (Yoon and Suh 2003) and leader-member exchange (Chow, Lai and Loi 2015) were found to contribute to OCBs in travel agencies. Some studies in the hotel sector also focus on the issue of OCBs (e.g.,Buil, Martinez and Matute 2016;Gonzalez and Garazo 2006;Lee et al. 2011;Ma and Qu 2011;Nadiri and Tanova 2010;Tang and Tsaur 2016;Wang and Wong 2011). For example, organizational identification, work engagement (Buil et al. 2016), employees’ emotional intelligence, job satisfaction (Lee et al. 2011;Nadiri and Tanova 2010), supportive climate (Tang and Tsaur 2016), national culture and leader-member exchange (Wang and Wong 2011) were found to lead to OCBs.

The above literature shows that, despite many studies attempting to identify factors that can influence OCBs, much extant research has ignored the role of tourism involvement and organizational commitment when examining OCBs.

1.4. Tourism involvement and organizational commitment

Recovery theory argues that removing work demand helps employees to recover from their work (Meijman and Mulder 1998). Participating in tourism has been identified as one of ways to recover from work demand (De Bloom et al. 2010). It helps employees to feel escapism and relief from job pressure (Rubinstein 1980;Yeh 2013). Meanwhile, employees’ psychological and physiological statuses return to baseline levels in terms of passive liberation from work and active involvement in tourism (De Bloom et al. 2010;Etzion 2003;Hobfoll 2001;Korpela and Kinnunen 2011;Meijman and Mulder 1998).

Organizational commitment psychologically links employees to their organization. Tourism can positively influence the experience of organizational commitment through recovery. When employees are sufficiently recovered from work, they feel more vigorous. They become more willing to work harder and devote themselves to work (Hobfoll1998,2001;Sonnentag 2003;Yeh 2013). The current study accordingly argues that, with increased tourism involvement, employees may experience higher levels of recovery. They may then demonstrate higher levels of organizational commitment. Specifically, this study hypothesizes that the positive influence of tourism on organizational commitment is higher among employees with higher levels of involvement.

Hypothesis 1: Tourism involvement is positively associated with organizational commitment.

1.5. Organizational commitment and OCBs

Organizational commitment is the extent to which employees perceive obligation toward their organization (Allen and Meyer 1996). Committed employees are inclined to perform beneficial behaviors exceeding job requirements because they feel more obligated to their firms (Wang and Wong 2011). These employees are then prone to become good organizational citizens (Ng and Feldman 2011). In addition, employees who feel valued tend to reciprocate with commitment through positive work behaviors, such as OCBs (Cohen 2003;Cropanzano, Rupp and Byrne 2003). Empirical studies have found a positive relationship between organizational commitment and OCBs (Cho and Johanson 2008;Cohen and Liu 2011;Djibo, Desiderio and Price 2010;Wang and Wong 2011). Therefore, the current study hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 2: Organizational commitment is positively associated with OCBs.

1.6. Tourism involvement and OCBs

Tourism affects OCBs through recovery. Recovering from work is of great importance for maintaining work performance (Quick and Quick 1984). As mentioned earlier, tourism involvement helps employees recover from work. If recovered, employees feel more vigorous and have enough resources to perform their jobs. They use less effort to complete in-role tasks and are willing to spend extra effort on extra-role tasks (Sonnentag 2003). If insufficiently recovered, employees need more effort to complete their daily tasks (Fritz and Sonnentag 2006) and they are less willing to dedicate themselves to extra work because this requires extra effort and resources (Hobfoll1998,2001). Therefore, feeling recovered by tourism involvement can help employees perform extra-role tasks and demonstrate OCBs. The current study further argues that the more employees are involved with tourism, the more recovery they may feel. Employees are able to complete in-role jobs by using fewer resources (Hockey 2000). The remaining resources are then used for performing positive extra-role behaviors at work. Accordingly, Hypothesis 3 is developed as follows.

Hypothesis 3: Tourism involvement is positively associated with OCBs.

1.7. Mediating effect of organizational commitment

This study has argued that the level of tourism involvement is related to organizational commitment and that organizational commitment in turn is able to influence OCBs. The relationship between tourism involvement and OCBs is implicitly expected to be mediated by organizational commitment. In fact, this expectation is supported by some management research, in which organizational commitment was found to perform a mediating role between variables (Clugston 2000;Hunt and Morgan 1994;Vandenabeele 2009;Yousef 2000). As such, this study developed the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between tourism involvement and OCBs is mediated by organizational commitment.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Sample

The Tourism Bureau, part of the Ministry of Transportation and Communication, Taiwan, had a list of 70 international hotels. 20 of these hotel firms were willing to participate in the current study voluntarily and confidentially. There are a variety of departments in a hotel. As aforementioned, due to frontline employees having direct encounters with tourists, their behavior and attitudes can significantly influence customers’ satisfaction (Xu et al. 2018). Therefore, the current study focused on frontline employees. Frontline hotel employees in the current study included employees in the food and beverage, front-desk and housekeeping departments. The current study delivered 500 questionnaires to human resource departments or staff of these hotel firms. They assured a random selection of respondents. This study finally received 336 (67.2%) valid questionnaires with anonymity.

There were 223 (66.4%) female and 113 (33.6%) male respondents. Of the 336 respondents, most were under 30 years old. Specifically, 39.3% and 35.7 % of the respondents were respectively between 20 and 25 years old and between 26 and 30 years old. Among the rest of the respondents, 15.5%, 6% and 3.6% were respectively aged 31 to 35, 36 to 40 and over 41. In terms of job type, 147 (43.8%) worked in food & beverage, 47 (14%) in the front desk and 142 (42.3%) in housekeeping. The average employee tenure was 2.4 years.

2.2. Measurement

The Consumer Involvement Profile Scale developed byGursoy and Gavcar (2003) was used to measure tourism involvement. Three dimensions, namely pleasure/interest (five items), risk probability (four items) and risk importance (two items), were included. This scale has been extensively adopted by much tourism and leisure research (e.g.,Gross and Brown 2006;Gursoy and Gavcar 2003;Huang, Gursoy and Xu 2014;Jain and Srinivasan 1990;Jamrozy et al. 1996;Park 1996;Prebensen, Vittersø and Dahl 2013;Xu, Kim, Liang and Ryu 2018;Yeh 2013). Moreover,Meyer, Allen and Smith (1993) developed a scale to measure organizational commitment which included three dimensions, namely affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment. Each dimension had six items. As to OCBs, the current study employed the measurement designed byPodaskoff et al. (1990). Based onOrgan’s (1998) definition of OCBs, this measurement includes five dimensions, namely, altruism (five items), courtesy (five items), sportsmanship (five items), civic virtue (four items) and conscientiousness (five items). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used to evaluate responses.

These three measurements were originally developed by English. A backward and forward translation approach was used to translate all questions into Mandarin (Hayashi, Suzuki and Sasaki 1992). The current study invited ten hotel frontline employees to participate in a pretest to ensure wording of questions, where no comment was made.

2.3. Data Analysis

The current study conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess model fit and validity. Sample profiles were described through descriptive analysis. A series of independent t tests were performed to examine the distinction in organizational commitment and OCBs between high and low tourism involvement groups. The levels of tourism involvement were divided at the 50th percentile of overall score. Respondents were accordingly classified into two groups, namely a highly tourism involved group and a low tourism involved group (Chang and Gibson 2011;Yeh 2013). In a similar manner, respondents were classified at the 50th percentile into a high and a low organizational commitment group. An independent t-test was performed to determine whether there was a difference in OCBs between the high and low organizational commitment groups. The structural equation model (SEM) was then performed to examine the hypotheses. The above analysis was conducted by using SPSS and AMOS software programs.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CFA, validity and reliability

To ensure that data best fit the measurement model, two competing models were examined. The first model, an 11-factor model, tested tourism involvement (3 factors), organizational commitment (3 factors) and OCBs (5 factors) as a first-order eleven-factor measurement. In the second model, tourism involvement, organizational commitment and OCBs were respectively tested as second-order measurements in which the abovementioned first-order factors were examined as sub-dimensions. To measure the model fit, several fit statistics were used, including χ², Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). For good model fit, χ² was expected to have significant p-values. The cutoff values were higher than .90 for IFI, TLI, GFI and CFI and lower than 0.10 for RMSEA (Hair et al. 2006). The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the second model had better model fit (χ² /df = 2.44, p = .00, IFI = .976, TLI = .967, GFI= .948, CFI = .976, RMSEA = .066) than model one (χ² /df = 4.57, p = .00, IFI = .814, TLI = .803, GFI= .585, CFI = .814, RMSEA = .103). As such, the current study used model two for the rest of the analysis.

To examine the convergent validity, standardized factor loading, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability were examined. The minimum requirement for standardized factor loading was 0.5 and the acceptable AVE and composite reliability were 0.5 and 0.7 respectively (Hair et al. 2006).Table 1 shows that every construct had standardized factor loadings greater than the threshold of 0.5 while the AVE ranged from 0.5555 to 0.7768. All exceeded the 0.5 rule of thumb. All composite reliabilities reached the acceptable level (0.7).

Regarding to discriminant validity,Hair and his colleagues (2006:778) suggested that the discriminant validity test can be performed to “compare the variance-extracted percentage for any two constructs with the square of the correlation estimate between these two constructs. The variance-extracted estimated should be greater than the squared correlation estimate”.Table 2 shows that all squared correlation estimates were less than the corresponding variance-extracted estimates. The results therefore supported that each construct had discriminant validity.

3.2. Independent t-tests

The means of tourism involvement, organizational commitment and OCBs were 3.69, 3.68 and 3.89 respectively. Standard deviations were 0.77, 0.83 and 0.65 respectively. As shown inTable 3, the highly tourism involved group (n=161) had mean scores of 4.17 in organizational commitment and 4.21 in OCBs. On the other hand, the low tourism involved group (n=175) had lower means of organizational commitment (3.22) and OCBs (3.60). Results of independent t tests displayed that the high tourism involvement group had significantly higher scores in organizational commitment (t=12.95, p < 0.01) and OCBs (t=9.90, p < 0.01) than the low tourism involvement group. In addition, the high commitment group had significantly higher scores in OCBs (t=10.03, p < 0.01) than the low commitment group.

3.3. Results of SEM

Table 4 shows that, as expected, tourism involvement positively and significantly influenced organizational commitment (β = 0.643, t value =12.572, p < 0.001). This result supported Hypothesis 1. As to Hypothesis 2, the results show that organizational commitment was positively related to OCBs (β = 0.429, t value =6.562, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was also supported. Hypothesis 3 proposed that tourism involvement was positively associated with OCBs. The results provide evidence to accept Hypothesis 3 (β = 0.359, t value =5.566, p < 0.001). Regarding Hypothesis 4, the Sobel’s test results (z = 6.456, p = 0.000) supported a significant indirect relationship (tourism involvement→organizational commitment→OCBs). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported. The direct, indirect and total effects of tourism involvement on OCBs were 0.359, 0.276 (0.643× 0.429) and 0.635 (0.359+0.276) respectively. That is, the mediation effect of organizational commitment between the relationship between tourism involvement and OCBs was 0.276.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the interrelationships between tourism involvement, organizational commitment, and OCBs. The current results demonstrate that tourism involvement was positively related to organizational commitment. These results suggest that recovery theory may be used as the framework to study the relationship between tourism involvement and organizational commitment. It is more likely that highly tourism-involved employees experience vigor and are more devoted to their job than low tourism-involved employees. In addition, employees’ organizational commitment was positively associated with OCBs. This result is consistent with existing literature (Cho and Johanson 2008;Cohen and Liu 2011;Djibo, Desiderio and Price 2010;Wang and Wong 2011). Moreover, tourism involvement was positively related to frontline employees’ OCBs. This finding provides evidence to the argument that highly tourism-involved employees tend to perform extra roles in their hotel firms than low tourism-involved employees. It also suggested that the influence of tourism involvement on OCBs could be explained by recovery theory. Furthermore, the current outcomes show that a significant positive effect of tourism involvement on OCBs exist when organizational commitment is the mediator. This indicates that the total effect of tourism involvement on OCBs could be enhanced when frontline employees are more committed to their hotel firms.

This study is the first to assess whether tourism involvement is related to organizational commitment and OCBs in the hotel industry. The significant influence of tourism involvement on work attitude and behavior found in this study makes theoretical contributions and has managerial implications for hotel firms. From a theoretical perspective, this study uncovers the positive role of tourism involvement in managing hotel human resources. It as such contributes to extant literature on organizational commitment and OCBs from the non-work viewpoint. It sheds a light on the linkage between work- and non-work related variables when investigating hotel human resources. In addition, the current outcomes support that recovery theory is a useful theoretical framework to explain how hotel employees recover from work via tourism involvement. This theory is enriched from merely describing the importance of work recovery to sustaining that tourism involvement is the antecedent of organizational commitment and OCBs. From a managerial perspective, since tourism involvement can be used to enhance job attitude and behavior, hotel managers should be informed of the contributions of tourism involvement. Being aware of this contribution, hotel managers can examine job candidates’ level of tourism involvement during the selection process, in addition to the examination of work experience, skills and knowledge. Moreover, once hotel firms are aware of the importance of tourism involvement on work performance, they should establish a supportive climate, encouraging current employees to get directly involved in tourism activities by offering holiday subsidies or increasing paid holidays. Hotel firms may also organize regular company trips for employees to participate.

This study has four major limitations. First, the current results are dependent on the responses provided by frontline employees in the hotel industry. In this context, a question of generalization is raised particularly when applying the outcomes to different employee categories. Future studies may find employees from different categories demonstrating different degrees of tourism involvement and showing different job-related performance. Second, the current outcomes are derived from a sample of hotels in Taiwan. Generalizing the outcomes to other countries should be done with caution. However, this study can be regarded as an exploratory study. Based on this study, future research can focus on hotel firms in other countries or regions to compare the differences in the effects of tourism involvement on work outcomes and to examine the cultural influence. Third, self-reported outcomes may raise a validity question. Respondents may exaggerate real job-related outcomes. Multiple data sources, such as supervisor interviews and annual evaluations, can be used in future research to gather consistent outcomes. Fourthly, the participating hotels gave this study assurance of randomly selecting respondents but this assurance is not examined. Future research may directly deliver questionnaires to respondents in order to guarantee random selection of participants.

In sum, frontline hotel employees perform a critical role in service encounters, so their work-related outcomes should be well investigated. This study is one of the first to assess whether tourism involvement influences organizational commitment and OCBs. Results demonstrate a significant interrelationship among tourism involvement, organizational commitment and OCBs, providing insight on how to manage tourism human resources. Hotel firms should be aware of factors contributing to organizational commitment and OCBs because having committed employees who are good organizational citizens can improve service quality.