INTRODUCTION

Tourism has experienced tremendous growth over the last few decades and has developed into a major industry in several countries. According to the World Tourism Organization, international visitors climbed by 4% to 1.5 billion in 2019 (UNWTO 2020). The Middle East is the fastest growing region for tourism, growing at an annual rate of +8%, followed by Asia and the Pacific (+5%) and Europe and Africa (+4%). Indonesia, as one of Asia's countries, is attempting to establish itself as a world tourism destination. Prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, Indonesian tourism has experienced a surge in recent years. International tourist arrivals (tourists) grew by 2.89 percent (13.62 million visitors) in 2019 compared to the 13.25 million foreign tourist visits in 2018 (Central Bureau of Statistics Indonesia 2019).

Along with the Covid-19 outbreak, the internet and technological advancements have the potential to influence views and tourism destinations (Govers, Go and Kumar 2007). Virtual reality is examined in this study as a path to encourage traveler to revisit a tourism destination. Virtual Reality is one of the technical developments that is gaining traction and popularity (VR). Early conceptual studies on virtual reality (VR) speculated on possible uses, if the depth and extent of sensory immersion will alter and increase routes of information distribution (Cranford 1996;Zhai 1998). In tourism, where informational communication about intangible items is always critical (Huang et al. 2016), the impending arrival of virtual reality is referred to as a new horizon (Williams and Hobson 1995), to virtual hazards (Cheong 1995). Marketing organizations’ online platforms with informative, engaging, and interactive media are more effective in indirectly influencing the perceived image of the destination and increasing interest and consequent intention to visit (Choi, Law and Heo 2016;Molinillo et al. 2018).

Motivational variables can impact a traveler's intention to visit or revisit a destination. Numerous prior research has demonstrated that tourists' future travel motivations have a beneficial effect on their cognitive and affective impressions of tourist destinations (Martin-Santana and Beerli-Palacio 2017;Madden, Rashid and Zainol 2016;Llodrà-Riera et al. 2015). Cultural motivations and values significantly influence visiting tourists' initial impressions (López-Guzmán et al. 2019).Li et al. (2010) demonstrated a causal association between motivation and tourist destination image, as well as the fact that motivation has a significant effect on cognitive and affective images. As a result, it is critical to understand why some people visit a tourist region especially in Indonesia. Travelers confront a variety of situational constraints (such as time, money, risk, jet lag, and disease outbreaks) that can influence their choice of destination. If tourist expectations of a destination are sufficiently strong, these situational limits can be overcome, allowing for travel (Chen, Chen and Okumus 2013;Li et al. 2011). Individuals must therefore resolve and overcome constraints to participate in tourism activities (Mlozi and Pesämaa 2013;Wang, Deng and Patrick 2018;Choi, Kim and Leopkey 2019).

The tourism industry in Indonesia and all its provinces, including Belitung Island as one of popular destination, cannot continue to expand because of the Covid-19 disease outbreak that has swept the country. According to data from theIndonesian Central Statistics Bureau (2020), foreign tourist arrivals to Indonesia decreased by 88.95 percent in September 2020 compared to September 2019. Along with the reduction in international tourist visits, the occupancy rate of participating hotel rooms, motels, and guesthouses decreased by 32.12 percent, with an average stay of only 1.73 days. Meanwhile, from January to May 2020, the number of foreign and domestic tourists visiting Belitung Island continued to fall. 793 foreign tourists and 11983 foreign tourists visited in January 2020, while only 1 (one) foreign tourist and 587 foreign tourists visited in May 2020. Given the limits imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic on Indonesian tourism development, particularly on Belitung Island, this study aims to gain insight into the virtual reality experience that has influence on destination image, as well as other supporting variables such as travel motivation and constraint, to investigate intention to revisit Belitung Island during the Covid-19 pandemic period.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Study Area

Belitung Island or Belitong, more commonly referred to as Billiton, is an island located off the east coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, between the Gaspar and Karimata Straits. The majority of the island's people are ethnic Malay who speak the Belitung dialect; others speak Hokkien China or Hakka. Beaches and small islands are the primary tourist attractions of Belitung. Tanjung Tinggi Beach and Tanjung Kelayang Beach both feature crystal blue ocean, sand, and rocky shores. Belitung Island is one of the Indonesian islands with a Special Economic Zone established by the President of the Republic of Indonesia on March 14, 2019. The zone is one of the top ten priority tourism destinations in the country, boasting marine tourism attractions with white sand beaches and exotic panoramas. With a total area of 324.4 hectares, the special zone's development plan is "Socially and Environmentally Responsible Development and Cultural Preservation," with a predicted workforce of 5,000 people in 2036. (Indonesia Special Economic Zones 2020).

1.2. Virtual Reality Experience

Virtual Reality (VR) is a term that is frequently used to refer to a certain type of technology. Virtual reality is the presence or awareness of being in one's current physical surroundings mediated by technology (Steuer 1992). In a nutshell, virtual reality can be characterized as a simulated experience that is either identical to or diametrically opposed to the real world. The potential of virtual reality in a variety of tourism subsectors has been demonstrated (Yung and Khoo-Lattimore 2019). Whether applied to education (Deale 2013;Huang et al. 2013), marketing (Huang et al. 2016;Pantano and Servidio 2011;Tussyadiah et al. 2018), cultural heritage (Dieck et al. 2018), or sustainability (Han et al. 2014), these technologies enable an unprecedented new and interactive mode of information dissemination. HMD (Head Mounted Display) VR is one well-known VR technology. HMD VR integrates the user's complete vision with a virtual environment that is navigated by spinning the head for a full 360-degree perspective (Steuer 1992). Respondents were given with a 360-degree video via YouTube media to answer research questions in this study.

The use of virtual reality head-mounted display (VR HMD) materials to learn about a destination has been shown to improve favorable feelings and intentions to visit (Gibson and O'Rawe 2018;Tussyadiah et al. 2018). The ultimate purpose of web-based destination marketing is to educate travelers about travel and to persuade them to visit through representative destination experiences (Huang et al. 2016). However, studies on innovation in tourism, and notably virtual reality, have primarily focused on research, akin to prototyping (Yung and Khoo-Lattimore 2019). By adopting the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis 1989), researchers assess respondents' behavior in terms of numerous factors, including usefulness and ease of use, which can eventually deliver the experience of using VR technology. The perceived utility and simplicity of use of virtual reality technology can influence users' intentions to use it (Vishwakarma, Mukherjee and Datta 2020). According toVenkatesh and Davis (2000), the TAM model seems to be the most influential in research. TAM has been used to describe the application of information technology in a variety of situations, including knowledge sharing systems in virtual communities (Koh and Kim 2004) and three-dimensional virtual worlds (Huang et al. 2013). Virtual reality experience is defined in this study as the result of a respondent's behavior while utilizing virtual reality technology based on VR HMD (360-degree views concept).

H1: Virtual reality experience has a positive influence on destination image

H2: Virtual reality experience has a positive influence on revisit intentions

1.3. Travel Motivation

Motivation is a psychology term that refers to the force that propels one's activities (Dann 1981). Travel motivation in this study is a term used in tourism research to refer to a collection of demands that motivate persons to travel to specific destinations or participate in specific tourism events or activities. Because travel motivation is a significant element in shaping tourist activities and behavior (Cha, McCleary and Uysal 1995;Crompton 1979), understanding why tourists travel is critical for researchers because it influences real behavior (Krishnapillai and Kwok 2020;Yousaf, Amin and C Santos 2018). Travel motivation is widely regarded as a critical notion for comprehending tourism behavior and the destination selection process (Crompton 1979), since it shapes a location's image both before and after a visit (San Martin and Del Bosque 2008;Huang and Hsu 2009).Beerli and Martin (2004) examined the relationship between visitors' perceptions of destinations and their motivations, as well as their prior vacation travel experience and sociodemographic variables. The findings indicate that motivation influences the affective image component; that tourist vacation experience has a substantial effect on cognitive and affective images; and those sociodemographic factors influence how cognitive and affective images are evaluated.

H3: Travel motivation has a positive influence on destination image

H4: Travel motivation has a positive influence on revisit intention

1.4. Travel Constraint

In general, constraints are seen of as negative consequences on an individual's engagement in a tourism activity. However, contradicting, and unexpected data from early constraint studies indicate that relationships between perceived barriers and behavioral outcomes are modest or weak (Kay and Jackson 1991). This conclusion is backed up by recent research (Zhang et al. 2012), which suggests that limitations do not always result in non-participation and can be successfully negotiated when varied levels of constraints are considered in conjunction with individual and other incentives. Thus, tourism studies have proved that the travel decision-making process is heavily influenced by destination image qualities, as individuals assess whether a possible tourist destination meets their wants and preferences (Sirakaya and Woodside 2005). Tourism constraints have been used to examine tourism restrictions associated with tourism or travel activities (Kang 2016;Moal 2021). Constraints have been intensively studied in leisure and tourist studies in recent decades (Kazeminia, Del Chiappa and Jafari 2015;Carneiro and Crompton 2010;Nyaupane and Andereck 2008;Jackson 2000). Several researchers, however, have examined inhibiting factors in the tourism context, including event tourism (Funk, Alexandris and Ping 2009;Kim and Chalip 2004;Hudson and Gilbert 2000;Nyaupane, Morais and Graefe 2004), sports tourism (Hinch et al. 2005;Hung and Petrick 2010;Jovanovic et al. 2013). The study shows that there are significant, distinct, and pervasive hurdles preventing people from travelling. Thus, identifying travel limits is critical for all tourism business stakeholders. This is primarily because constraints play a significant part in the destination selection decisions made by individuals or organizations (Jackson 2000). Based on the literature above, this study conceptualizes that all risks that occur in tourist travel from the place of origin to the destination are referred to as travel constraints.

H5: Travel constraint has a negative influence on destination image

1.5. Destination Image

Destination image is one of the most extensively researched issues in tourism scholars (Fakeye and Crompton 1991;Tapachai and Waryszak 2000;Afshardoost and Eshaghi 2020). Several studies concur on its capacity and power to affect not just customer views of tourism destinations (Baloglu and McCleary 1999;Beerli and Martin 2004), but also revisits (Simpson et al. 2020), as well as the elements that drive destination image construction (Vinyals-Mirabent 2019). The image of a destination is a critical component that might influence tourists' destination choice decisions (Beerli and Martin 2004).Zhang et al. (2014) discovered that destination image is substantially associated with behavioral loyalty (intention to visit and revisit) and composite loyalty (behavioral intention).Jalilvand et al. (2012) discovered that a positive image of a destination has a beneficial effect on tourist attitudes and intentions to revisit, and that tourist attitudes have a substantial association with the intention to travel again. Tourist attitudes refer to the psychological dispositions that are represented through tourists' positive or negative judgments of specific activities. Indeed, tourist sentiments are a strong predictor of visitors' travel selections to certain destinations (Nicoletta and Servidio 2012).

H6: Destination image can have a positive influence on revisit intention

According toYung et al. (2021), virtual reality can elicit both information-rich (cognitive) and enjoyable responses (affective). Investigating the impact of VR on destination image creation will provide critical insights for destination marketing firms (Marasco et al. 2018). Prior to their arrival, tourists gather cognitive information through a variety of means, including word of mouth, television, pamphlets, and the internet (Werthner and Ricci 2004). Visual media content has been proven to be the most influential contributor to destination image (MacKay and Fesenmaier 1997;Mariani, Di Felice and Mura 2016) and ultimately persuades tourists to visit (Huang et al. 2016) or revisit (Yoon et al. 2021).

H7: Destination image can mediate virtual reality experience and revisit intention

The term "destination image" refers to a collection of thoughts and impressions formed over time because of the processing of data from numerous sources that results in a mental representation of the features and benefits desired from a destination (Zhang et al. 2014). Previous study has confirmed that destination image influences customer behavior factors before to, during, and after a visit (Tasci and Gartner 2007;Altintas, Sirakaya-Turk and Bertan 2010;Madden, Rashid and Zainol 2016). Destination image refers to an individual's total perception of a location, with cognitive and affective elements interacting in complicated ways (Crompton 1979). Additionally, individuals who believe that travel is critical to their lives should travel more, while earlier research has indicated that purchasing decisions for specific tourist locations should be influenced by travel constraints (Chen, Chen and Okumus 2013;Nyaupane, Morais and Graefe 2004).

H8: Destination image can mediate travel motivation and revisit intention

H9: Destination image can mediate travel constraint and revisit intention

2. METHODOLOGY

Respondents in this study were travelers with prior tourism experience to Belitung Island, Indonesia's tourist sites. From May to September 2021, surveys with a Likert scale of 1-5 (strongly disagree-strongly agree) were distributed using the Google Form application. This research was exploratory in nature. According toBabin and Zikmund (2015), exploratory research is study that tries to clarify confusing situations or to uncover potential opportunities. The convenience sampling approach was employed to collect data. As the name implies, convenience sampling entails the collection of data from members of the population who are willing to share it (Sekaran and Bougie 2019). Convenience sampling is most frequently employed during the exploratory phase of research and is arguably the quickest and most efficient technique to collect some basic information.

Data collection approach for this study is an online survey using social media. One way for people to express themselves in the modern era is through online communication platforms such as WhatsApp. WhatsApp is an online social media platform that enables users to communicate with one another or with a large group of people. Verbal and non-verbal communication are critical tools for researchers to decipher the status of a destination's image. Examples of virtual reality content that incorporates the concept of 360-degree views are also released via social media to address the research questions. Recent study fromSchultz et al. (2011) demonstrate that people are more truthful and bolder when communicating their thoughts, opinions, and comments via a digital screen rather than in person. Thus, with WhatsApp, researchers can overcome the issue of assuring a representative sample by selecting acceptable target respondents from the vast and diverse number of WhatsApp groups available in Indonesia.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Data Collection

This survey has a total of 250 respondents that can offer responses. Table 2 below summarizes the outcomes of processing respondent data by gender, age, area, education, travel information sources, and frequency of travel.

Based on survey results, there are 250 respondents from Indonesia's major cities, with 96 males (38.5%) and 154 females (61,6%). There are 89 respondents aged under 20 years (35,6%), 91 respondents aged 21-30 years (36,4%), 38 respondents aged 31-40 years (15,2%), 22 respondents aged 41-50 years (8,8%), and 10 respondents aged above 51 years (4%). There are 26 respondents (10,4 percent) with only a high school education, 20 respondents (8 percent) with a diploma, 135 respondents (54%) with an undergraduate degree, and 69 respondents with graduate degree (27,6%). According to travel information sources, 181 respondents chose social media (72,4%), 8 respondents chose e-commerce apps (3,2%), 8 respondents chose newspapers (3,2%), 2 respondents chose magazines (0,8%), 6 respondents chose websites (2,4%), 28 respondents chose friends (11,2%), and 17 respondents chose family (6,8%). Finally, respondents who visit only once (1x) account for 180 respondents (72%), while those who visit twice (2x) account for 10 respondents (4%) and those who visit more than twice (>2x) account for 60 respondents (24%).

3.2 Validity and Reliability

The study hypothesis will be validated by describing the structural equation model's outcomes. The validity of a hypothesis is confirmed by the collection of data. A hypothesis is defined statistically as a statement about the status of the population that will be tested for validity using data from the research sample (Sekaran and Bougie 2019. To aid in data processing and hypothesis testing, this study makes use of the Windows-based Smart PLS v.3 application. PLS-SEM assumes that the data are not normally distributed. Due to the absence of normality, the parametric significance test utilized in regression analysis cannot be used to determine the significance of loading factor, and path coefficients. By contrast, PLS-SEM employs a nonparametric bootstrap approach to determine the significance of the coefficients (Davison and Hinkley 1997).

As shown in Table 3 below, all constructs have loading factors more than 0.7, indicating that all latent variables have good convergent validity. The loading factor values reveal the degree of variation in the data, which is critical for understanding latent construction. Meanwhile, reliability is determined by Cronbach's alpha values. Cronbach's alpha value greater than 0.7 implies a high degree of internal consistency (Hair et al. 2017). Similarly, the composite reliability (CR) rating of greater than 0.70 indicates that the study's constructs are all dependable.Moreover, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value must be more than 0.50, indicating that the construct explains for more than half of the indicator variance on average. Finally, heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) is used to determine the discriminant's validity, if HTMT (confident interval high) value is below 0.90, discriminant validity has been established between two reflective constructs (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt 2015). Result of HTMT values is shown in Table 4.

Based on the results of the data in Tables 3 and 4, each variable has a loading factor value above 0.7, a CR value above 0.7, an AVE value above 0.5, and HTMT confidence interval value below 0.9, indicating that the construct used in this study is acceptable and can be proceed to the next step to test the hypothesis.

3.3 Hypothesis Testing

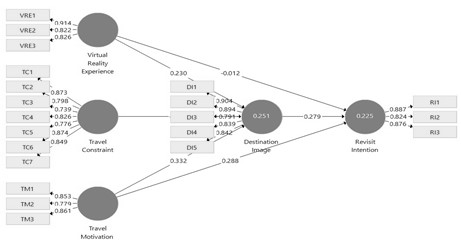

The hypotheses are tested using the findings of the inner model (structural model) test, which comprise the R-square output, parameter coefficients, and t-statistics. To determine the acceptability or rejection of a hypothesis by examining the significant value between constructs, t-statistics, and p-values. The rule of thumb applied in this study is that a t-statistic more than 1.96 with a p-value less than 0.05 is acceptable.

From the hypothesis test's results, particularly on direct effect, it shows that virtual reality experience (VRE) has a positive influence toward destination image (DI) (ß = 0.230, t-stat = 3.794, p < 0.05 (0,000)) and has a negative influence toward revisit intention (RI) (ß = -0.012, t-stat = 0.222, p > 0.05 (0,825)). Travel motivation (TM) has positive influence toward destination image (DI) (ß = 0.332, t-stat = 5.228, p < 0.05 (0,000)) and revisit intention (RI) (ß = 0.288, t-stat = 4.474, p < 0.05 (0,000)). Travel Constraint (TC) has negative influence toward destination image (DI) (ß = -0.131, t-stat = 3.211, p < 0.05 (0,001)). Destination Image (TC) has positive influence toward revisit intention (RI) (ß = 0.279, t-stat = 4.706, p < 0.05 (0,000)).

3.4 Discussion

In our experiment, we used an example of a video about a tourist site on the island of Belitung to provide cognitive-affective signals to respondents to create an immersive environment in which they could focus and participate more effectively in virtual reality. The findings indicated that participants had a greater level of familiarity with travel planning. Video appears to have increased their capacity for suspension of disbelief, resulting in their willingness to focus on virtual reality. According to the findings of the preceding hypothesis, virtual reality experience has a direct negative effect on revisit intention and destination image can mediate virtual reality experience and revisit intention. Those results are because visitors' intentions to revisit are influenced by the activation of both rich knowledge (cognitive) and enjoyment (effective) (Yung et al. 2021), and so virtual reality cannot directly influence revisit intention in this study. Cognitive and affective knowledge should coexist with any definition of virtual reality concept. Without cognitive and affective knowledge from a destination, no concept of virtual reality experience can be imagined. Prior to their travel, tourists gather cognitive information through a variety of means, including word of mouth, television, pamphlets, and the internet (Werthner and Ricci 2004). Visual media has been identified as the most significant contributor to the destination's image (MacKay and Fesenmaier 1997;Mariani, Di Felice and Mura 2016). Because virtual reality experiences with 360-degree views concept are visual in nature, they can be said to greatly contribute to the creation of the destination's image in this study is Belitung Island. Visual media can provide more data-rich content, contributing to the cognitive and affective components that eventually drive tourists' desire to return. In this study, the virtual reality experience shown that improved visual display, as well as increased engagement, resulting in increased positive information transmission.

Tourist motivation to travel is critical to investigate since it has an impact on actual behavior (Dolnicar and Leisch 2008;Kim, Goh and Yuan 2010). The actual behavior in this study could be in the form of a return to Belitung Island for travelers. Travelers because of internal forces (desiring relaxation, excitement and adventure, and entertainment), as well as external forces associated with destination features. The study's destination attributes focus heavily on push motivation, which derives its internal power from intrinsic motivations such as the desire for rest and relaxation, escape, sociability, and status (Andreu et al. 2005;Park and Yoon 2009). This study finding is consistent with the findings ofHsu and Huang (2012) andSoliman (2021), who found that travel motivation had a significant and direct effect on destination image and revisit intention to travel. The participants informed us that returning to Pulau Belitung will enable them to have unique experiences and boost their sense of relaxation, adventure, and amusement. Given the limited amount of prior research on travel motivation, someone might argue that these findings indicate that tourists' attitude toward obtaining internal happiness in exchange for revisiting a destination is controlled by their travel motivation.

The prevalent view in the literature is that tourism destination selection is constrained (Tan 2020). That is, constraint have a major impact on travelers' intentions to visit or revisit (seeChen., Hua and Wang 2013). As a result, travel can occur only if the traveler's motivations (e.g., intention to revisit) are sufficiently powerful to overcome constraints. While individuals may and do overcome and manage with limits when engaging in leisure activities (Sparks and Pan 2009), there is a lack of studies addressing the relationship between travel constraints and the intention to revisit.Nyaupane and Andereck (2008) found that perceived travel constraints had a negative impact, and in some cases a significant, impact on destination image, and hence on intention to visit, without elucidating the fundamental links between them. By proposing and empirically testing the mediating model of destination Image, this study contributes to the literature. The testing results indicate that travel constraints have a direct effect on revisit intention; additionally, destination image mediates the effect of travel constraints on revisit intention in such a way that including destination image as a predictor of revisit intention in addition to travel constraints significantly increases the impact of constraints on revisit intention. In other words, the results of testing the mediating model of destination image indicate that destination image, as a unique mediator, has the potential to mitigate the negative effect of perceived limits on revisit intention.

4. CONCLUSION AND LIMITATION

Empirically, the findings of this study provide knowledge and input to those involved in the tourism industry, particularly the local government of Belitung Island, to motivate a well-designed marketing program aimed at increasing tourist visits to Belitung Island in the period following the Covid-19 pandemic's cessation. Virtual reality technology, namely videos with a 360-degree view concept, is intended to attract the interest of local and national tourists in revisiting tourist locations on Belitung. According to this study, the negative impact of travel barriers can be mitigated to a great extent, hence increasing the intention to revisit. More crucially, and perhaps because of the mediating influence of a destination's image, destinations must recognize the importance of adopting high-quality marketing programs that can help them improve their own image in the target tourism market. The study's findings indicate that domestic tourists can overcome and lessen travel constraints using negotiating methods, resulting in a desire to return to Belitung Island. Thus, the negotiation process's beginning and outcome are contingent on the relative strength and direction of preferences conveyed through virtual reality experience, travel motivation, and destination image. Numerous theoretical implications follow naturally. To begin, this data casts doubt on the researchers' initial assumption that limitations have a monolithic effect on travel behavior. This study questions the widely held belief that restrictions are insurmountable impediments to participation. However, this study discovered that destination image is critical in determining the association between virtual reality experience, travel constraints, travel motivation, and intention to revisit.

This study has several limitations. First, most study participants were domestic visitors from Indonesia's major cities. As a result, the findings may be limited in their generalizability. Future research may benefit from a pluralistic approach to demographic factors when they are used to evaluate revisit a destination. Second, this study is lacking attributes for each variable, most notably virtual reality experience and travel motivation. Virtual reality experiences in tourist literature are comparatively rare and pull factor of motivation can be used to strengthen future research findings. Third, because this study evaluated destination images using an attribute-based technique rather than a holistic one, the study lacked the distinctive holistic characteristics of destination images. Future research should use a qualitative methodology to elicit the destination image's distinctive holistic elements to determine whether these holistic image features reinforce this mediation impact.