INTRODUCTION

The importance of social media in the wider hospitality industry has evolved from novelty to necessity. The changing attitude toward social media within the industry is evidenced by growing scholarly attention on the technology, in both quantity and scope. Earlier works on social media use in the hospitality industry had focused on the potential of the “relatively new” technology and the eccentricities of its disruptive nature and capacity (Kasavana et al., 2010, p. 79). Understandings of social media in hospitality has since evolved to the point where studies are utilizing big data and analytical approaches (e.g., Jimenez- Marquez et al., 2019; Lamest & Brady, 2019). However, there is scope to better understand the breadth of the literature, and resultingly what actors are doing with social media within the hospitality industry. It is appropriate, therefore, to periodically review the hospitality literature pertaining to social media and provide an accurate assessment of current trends.

Key reviews of literature examining the use of social media in the hospitality and tourism industries have included: Lu and colleagues’ (2018) encapsulation of 105 works between 2004 and 2014, and a content analysis by Leung et al., (2013) of studies between 2007 and 2011, with both papers focusing on tourism and hospitality. Lu et al., (2018) reported that to the year 2014, the state of hospitality social media research was still developing as evidenced by several research gaps. Apparent gaps in the literature were also observed by Leung et al., (2013), who added that social media use presented strategic and competitive potential for tourism operators. These papers serve an adequate purpose in investigating the broad application of social media within the tourism and hospitality industries, however, given the evolution of social media in the second half of the 2010s, it is necessary to continue to update this knowledge. Further, it would benefit the hospitality industry to undertake a systematic review of literature on social media specifically within this sphere of knowledge.

It is key for scholarship to periodically update the consensus among the literature. This is especially true for the topic of social media, given it is a disruptive and rapidly evolving technology, which has maintained broad application and reach within the hospitality industry. Thus, this study aims to fulfil the need for current understandings to be presented by applying a systematic approach to collecting the literature and employing Leximancer to analyze the state of research, specifically over the decade from 2010 to 2020. Utilizing Leximancer allows for the identification of concepts within the selected literature, enhancing the information which the review can provide (Cretchley et al., 2010). By adopting a systematic approach, in this manner, this study provides the grounds for periodic comparative assessments of social media use in the hospitality to be undertaken, whilst also providing an update on the current trends and themes of the scholarship. Specifically, this review is differentiated by its intentions to provide both sound structured review data whilst also utilizing Leximancer to enable analysis of current and emergent research themes.

METHODS

To provide a comprehensive update on the research state of social media use in the hospitality sector, this study employs the systematic literature review methodology to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the existing literature (Okoli & Schabram, 2010). The systematic review is a widely used method of literature review, which allows for understanding of the breadth of research in a specific field (Tranfield et al., 2003) and provides reliable assessments of the relevant studies on a specific topic (Gough et al., 2017). This review specially adopts a hybrid-review structure (Paul & Criado, 2020), considering the incorporation of structured review and narrative elements supported by Leximancer analysis. After identifying the research purpose and goals of the review, a research protocol including the scope of the study, criteria, quality assessment and data extraction was developed as recommended by Okoli & Schabram (2010), leading to the search for the most necessary literature.

Data collection

Peer reviewed research papers on social media in the hospitality sector were identified and gathered from three online research databases including Science Direct, EBSCOHost, and Google Scholar. These three online research databases are recognized as the largest and most popular in searching for research papers in hospitality and tourism management (Buhalis & Law, 2008). Search strings were constructed using the following terms: ‘hotel’, ‘hospitality’, ‘social media’, ‘online review’, ‘user-generated content’, and ‘online social networking’. These terms appeared in the titles, keywords, or abstracts of the identified papers. The journals in which the papers were published were screened to confirm publications and ranking in the ABDC (Australian Business Deans Council) journal list. This assisted in the process to select high quality research papers within the scope of years from 2010 to 2020, at the time of the data collection. The ABDC ranking has been used at universities and business schools in Australia and New Zealand as a reference for journal quality, including across the areas of hospitality and marketing.

In addition, the direct relevance to the focus of this study was considered by reading the title, abstract and keywords of each article. To ensure the validity and avoid missing any relevant papers, the authors conducted the search independently between January and March 2021 and the final lists were combined using a Microsoft Excel database. The pool of 165 papers was selected for this study, with the exclusion criteria of duplication, in-press papers, commentaries, and book reviews. The collected papers were categorized by key information such as author(s), journal name, paper title, publication year, ABDC journal rankings, perspective (e.g., consumer, supply), methods and samples used in the research (e.g., method for collecting and analyzing data, range of industry sectors, type of social media), abstracts with key words, key measurement models/ frameworks and theories/approaches used.

Data analysis

The number of publications by year was recorded as cumulative frequency and analyzed under two phases (i.e., phase 1: 2010-2014, phase 2: 2015-2020). Journal titles and their ABDC journal ranking were coded and recorded as frequency and percentage. Key measurement models/frameworks and theories/approaches used were coded and classified as cited or applied for comparison. Samples used in the research were coded as frequency and/or percentage which were then classified under industry sectors, and social media applications. The number of perspectives (e.g., consumer, supply, or both) in each article was coded and analyzed in each year. The methods used were classified as detail of the methods (e.g., online survey, interview, observation etc.) and type of data (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, or both). The key data analysis was coded as frequency and classified under types of main data analysis methods reviewed in this study.

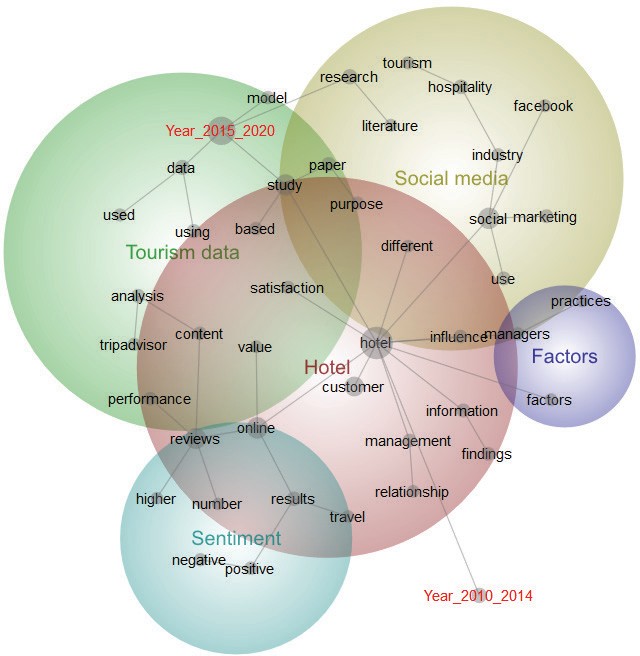

Abstracts with keywords were qualitatively analyzed by Leximancer (version 4.5) to investigate key themes and concepts. Prior to the use of Leximancer, the data were arranged in Excel. In the first column, two phases (i.e., phase 1: 2010-2014, phase 2: 2015-2020) were recorded for comparison by year and abstracts with keywords were recorded in the second column. The Excel spreadsheet was uploaded in Leximancer and based on frequency occurrence of a concept, a concept map was produced to display the main themes and concepts visually. The larger colored circles represented the important themes and small gray nodes represented the concepts generated in each theme. In this analysis, Leximancer identified where each year phase was closely situated relative to the relevant dominant themes. Also, Insight Dashboard in Leximancer was used to compare the relative frequency and the strength of prominent concepts for each year phase. The relative frequency explains a conditional probability and the strength score is the reciprocal conditional probability (Leximancer, 2021). This approach highlighted the change of key research topics over time.

RESULTS

A total of 165 peer reviewed research articles on social media in the hospitality sector, published between 2010 and 2020, were included in the systematic review. Analysis of the reviewed articles was reported in terms of: (1) number of publications by year and journal; (2) theoretical base; (3) range of industry sectors and social media; (4) perspective of research; (5) research methods and data treatment (which represent the elements of structured review undertaken in this study); and (6) key themes and concepts (informed by Leximancer).

Number of publications by year and journal

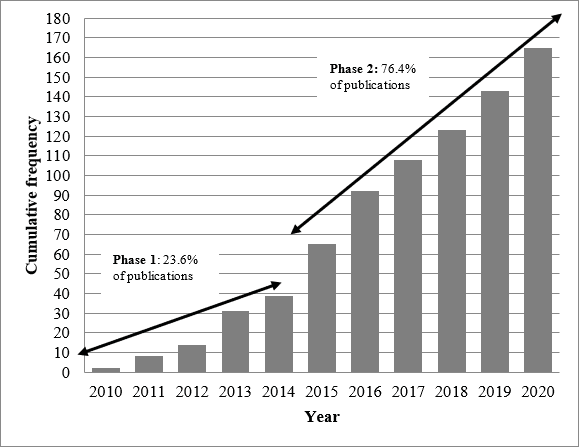

From the initial year of collection in 2010 there was slow, but incremental, growth to fourteen total articles by 2012. Scholarship experienced significantly greater interest in 2013, in which seventeen articles were identified, more than doubling the scholarship, depicted in the cumulative frequency chart (see Figure 1). There was a considerable acceleration of publications at the midpoint of the decade (2015 to 2016), whereby 26 and 27 articles were identified, representing almost one third (32.1%) of all publications analyzed in this study. Interest remained steady (16 and 15 publications) for the next two years (2017 and 2018), before, again, growing slightly (20 and 22 publications) in the last two years (2019 and 2020) of the decade. As indicated in Figure 1, there are two observable phases for interest in the literature. These phases occurred prior to 2015, (Phase 1: 23.6 % of publications) (e.g., Blal et al., 2014; Bulchand-Gidumal et al., 2013; Cabiddu et al., 2014; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014; Chan & Guillet, 2011; Chaves et al., 2012; Gu & Ye, 2014; Kasavana et al., 2010; Kim et al, 2011; Kleinrichert et al., 2012; Levy et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Mauri & Minazzi, 2013; Noone et al., 2011; Park & Allen, 2013; Sparks & Browning, 2011; Verma et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2011 etc.) and from 2015 (Phase 2: 76.4% of publications) (e.g., Albayrak et al., 2021; Amaro et al., 2016; Ayeh et al., 2016; Bigné et al., 2020; Buhalis & Sinarta, 2019; Casaló et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2016; Garrido-Moreno et al., 2018; Gavilan et al., 2018; Giglio et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2015; Kim & Park, 2017; Leung & Tanford, 2016; Li & Ryan, 2020; Ma et al., 2018; Michopoulou & Moisa, 2019; Mkono & Tribe, 2017; Moro et al., 2019; Murphy & Chen, 2016; Neirotti et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2015; Phillips et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2020; Su et al., 2015; Torres et al., 2015; Tung et al., 2018; Viglia et al., 2016; Yang, 2020; Yen & Tang, 2015, Zhao et al., 2019 etc.).

Table 1 depicts the distribution of articles by journal, and further segmenting this distribution by ABDC ranking. In compiling the 2019 version of the ABDC guide, a quality rating system was used along with four rating categories A*, A, B, and C. The greatest percentage (45%) of research was present in A-ranked journals, with the bulk of those sourced from three journals: International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, and Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. The next highest percentage (32%) of articles collected for this study were from A*-ranked journals with 73% of those articles published in either: International Journal of Hospitality Management, or Tourism Management. The remaining 24% of articles were collected from B and C-ranked journals, with the minority of articles (n=7), collected from two C-ranked journals. The bulk of B-ranked literature was published by the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, with 45%, there was a remainder of multiple journals from which one article was collected (shown in Table 1). The leading journal in each ranking, included ‘hospitality’ in the title.

Figure 1: Cumulative frequency of the 165 peer reviewed research papers examining social media in the hospitality sector by year published

Theoretical base

Across the 165 papers identified in this systematic review, 102 papers evidently included at least one citation, discussion, or similar note of theories, models, frameworks, and approaches. There was a total of 135 occurrences of at least one mention of theories, models, frameworks, and approaches occurring within those 102 papers, and 55 instances where these were identified to have been specifically applied to the research as a theoretical base. There were 63 papers which, for various reasons (e.g., theoretical and review papers), did not evidently utilize, or explicitly mention a theoretical base. In some cases, however, multiple theoretical bases were utilized or mentioned in a single paper and these were included in the total count in Table 2.

Presented in Table 2 are the most apparent of the theoretical bases identified in the literature. Additionally, beyond the scope of Table 2, were 28 papers in which a theory, and 38 papers in which a model, framework, or approach was noted (or indeed applied as the theoretical base) at least once, however those 66 theoretical approaches were only identified on these singular occurrences. The eWOM approach (Litvin et al., 2008) was eight times more apparent than the next most evident theoretical basis; the uses and gratification (U&G) approach/theory (Katz et al., 1974; Stafford et al., 2004), which appeared in five papers, and was applied in three papers. The occurrence of eWOM in the literature aligned with the proclivity of social media being treated as an electronic form of communication, and as a source of data. The other theories, models, frameworks, and approaches of note in this review were: resource-based view theory (Grant, 1991), user generated content approach (Wright & Zdinak, 2008), motivation theory (Herzberg, 1968; Maslow, 1987), the technology acceptance model (Davis, 1989), grounded theory (Strauss, 1987), Herzberg’s two-factor theory (Herzberg, 1966), justice theory (Greenburg, 1987), social capital theory (Putnam, 1995), and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1988).

Table 2: Sample of theories, models, framework, and approaches featured in the 165 research papers on social media applications in the hospitality sector examined in this study

1 Cited, discussed or mentioned at least once in a paper but not evidently applied in the paper.

2 Applied, demonstrated, and explicitly researched through methods in the paper. Applied is a sub-group of Appeared.

3 Total < 165. A total of 63 papers neither cited nor applied specified theories, though some papers cited or applied more than one theory, model, or approach.

4 Total = 135 including an additional 66 theories or models, framework, and approaches appeared or were applied once, beyond the scope of this table.

Range of industry sectors and social media

The frequencies of industry sectors investigated in this study are shown in Table 3. As some papers investigated multiple sectors there were 177 instances of industry sectors examined in the literature. The most frequently investigated sector were hotels, featuring in 154 papers. This was exponentially more featured than the remaining industry sectors, which were: hospitality (n=12), tourism (n=7), restaurants (n=2), resorts (n=1), and airlines (n=1). Thus, within investigations of social media in hospitality, there was a clear focus on the hotel sector.

Table 3: Industry sectors in the 165 research papers on social media in hospitality examined in this study

Industry Sectors | |

|---|---|

Range of industry sectors | 177 1 |

Hotel | 154 |

Hospitality | 12 |

Tourism | 7 |

Restaurant | 2 |

Resort | 1 |

Airline | 1 |

1 Total >165. Some papers covered multiple sectors.

Table 4 shows the social media applications which appeared in the literature examined in this study. Given that numerous studies investigated or utilized various social media applications, the frequency of which applications were mentioned exceeds the sample of 165 papers. The abundance of literature captured in this review necessitated that only applications appearing on multiple occasions were represented in Table 4, thus the omission of fifteen singularly appearing social media applications: Airbnb, Ciao.co.uk, Daodao.com, Google, Hotels.com, Hostelworld, Instagram, Makemytrip.com, Ozome, Sina Weibo, Tencent Weibo, Travelocity, TravelPost, TrustYou, and Venere.com. The most featured social media application was TripAdvisor, which was present in 26.7% of the literature. Facebook (12.5%), Twitter (4.9%), Booking.com (4.2%), Expedia (3.8%), and Yelp (3%) were the other significantly appearing social media applications. In 28 publications, though some form of social media appeared to be utilized in the research, specific applications were not identified within those studies. There were also 21 studies which did not appear to utilize, or discuss, specific social media applications (such as theoretical papers), though social media as a concept was still addressed. The nature of some of the studies included in this review necessitated a focus on fictitious social media, and this occurred in 19 studies.

Table 4: Social media applications used in the 165 research papers on the hospitality sector examined in this study

Total 2651, 6

1 Total > 165. More than one social media application examined in most papers.

2 Does not add to 100% due to rounding.

3 Specific social media applications were not evident in certain studies.

4 Social media applications were used, but not explicitly identified.

5 Fictitious social media applications were constructed for the purpose of the study.

6 Various studies specifically identified one social media application, these 15 are unique from the remaining list.

Perspective of research

The breakdown of the two perspectives of the literature (consumer and supply), over time, is presented in Table 5. There was a somewhat greater proportion of consumer-focused literature (56%) than supply-focused literature (40.4%). There did not appear to be a clear trend in preference between perspectives over time though in 2016, scholarship that favored the consumer perspective was more than double. Six papers (3.6%) did not evidently focus on either perspective. One paper was found to have investigated both the consumer and supply perspectives, accounting for the total in this case being one greater (n=166) than total valid articles examined in the study. As for the foci of supply-oriented literature, researchers’ focus tended toward a supplier perspective on marketing (29 papers), customer relationship management (CRM) (18 papers), and sales performance (13 papers). The foci within the supply-oriented literature were excluded from the totals in Table 5 as some papers did not maintain a singular focus. Though social media marketing was the specific focus on just four occasions, it is possible that social media marketing was integrated in papers with the larger marketing focus, with the concept of social media marketing gaining attention as the decade progressed.

Table 5: Research Perspectives and focus areas of supply-oriented research from 165 research papers on social media in the hospitality industry

1 Total is calculated via the number of papers: consumer, supply, or N/A, for each year and total.

2 Supply perspective foci are not included in the total, as more than one focus was present in some cases.

3 One paper focused on both consumers and supply perspective, thus adding one to total number of papers >165.

Research methods and data treatment

The research methods and modes of data analysis utilized in the 165 research papers are shown in Table 6. There was a clear tendency toward quantitative analysis (n=107, 64.8%) in the scholarship, with only 21.8% of papers (n=36) assuming a qualitative approach and the remaining 13.3% of papers (n=22) adopting a mixed methods approach. The quantitative preference of the literature is reflected in the key data analysis methods, with content analysis (n=39), regression analysis (n=35), descriptive analysis (n=32), structural equation modelling (SEM) (n=30), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) (n=23) among the most used data analysis methods. Qualitative studies also account for the prevalence of content analysis as a key method, and for the use of thematic analysis (n=12). Regarding the prevalence of content analysis, this is accounted for by the high frequency of content (n=72) as the main source of data. Other prevalent data sources were online surveys (n=56), interviews (n=23) and web crawling (n=17) also among the most employed data. Web crawling, along with text mining/analysis (n=3) reflect the data heavy nature of social media research and reflect the occurrence of sentiment analysis (n=8) and natural

language processing (n=8) among the data analysis methods. As with prior tables, the preponderance of data collected in this review necessitated that Table 6 present the most apparent methods, with some eleven other data collection methods, and 51 methods of data analysis employed across the scholarship.

Table 6: Research methods used, samples and perspectives in the 165 research papers on social media in hospitality

Key themes and concepts

The five main themes and their connectivity rates were Hotel (100%), Social media (45%), Tourism data (15%), Sentiment (9%), and Factors (7%), in order of relative importance (see Figure 2). These were the main themes, including several relevant

concepts representing key research topics, in the abstracts with keywords, in the 165 research papers on social media in the hospitality sector examined in this study. Hotel was the most significant theme and mentioned 707 times in the 165 abstracts with keywords, which is unsurprising given Table 3 shows hotels as the most investigated within the hospitality sector. The Hotel theme included the relevant concepts of ‘online’, ‘reviews’, ‘customer’, ‘management’, ‘influence’, ‘satisfaction’, ‘value’, and ‘relationship’. Therefore, the concepts relevant to the Hotel theme suggest extant social media research of the hotel sector tends to focus on the possible impacts of customer satisfaction, relationships, and value on management decisions. Social media was the second theme, mentioned 538 times in the 165 abstracts with keywords. The relevant concepts to Social media as a theme were: ‘marketing’, ‘industry’, ‘managers’, ‘tourism’, and ‘Facebook’. This theme seemed to reflect the research topic about social media (especially, Facebook) study in tourism marketing industry. The third theme Tourism data was mentioned 369 times in the 165 abstracts with keywords. The concepts of ‘analysis’, ‘content’, ‘performance’, ‘model’, and ‘TripAdvisor’ were fairly related hence the analysis of tourism content (especially, from TripAdvisor) using a model, could be regarded as one of main research topics in the 165 research papers examined in this study. The fourth theme Sentiment was mentioned 152 times and contained the concepts of ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘travel’, ‘number’, and ‘higher’. This theme was apparent as the research topic in studies such as those regarding positive and/or negative travel experiences based on the higher number of reviews. The last theme, Factors, had relatively fewer relevant concepts such as ‘factors’ and ‘practices’. Therefore, it was possibly regarded as the research theme in terms of potential impact of factors related to the conduct of practices within the industry.

Figure 2: Key themes and concepts in the 165 research papers on social media in the hospitality sector examined in this

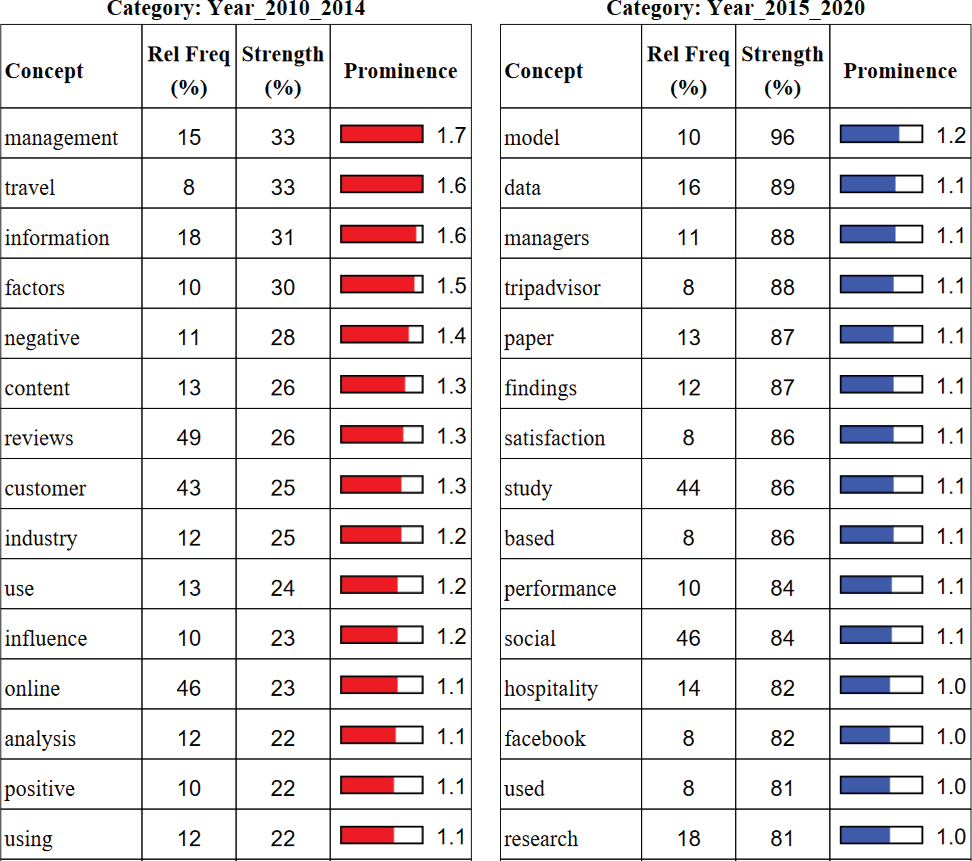

Through Insight Dashboard in Leximancer, two year phases (i.e., phase 1: 2010-2014, phase 2: 2015-2020) were compared according to the relative frequency and the strength of prominent concepts (see Table 7). In the phase 1 from 2010 to 2014, the concepts highly scored on the strength, such as ‘management’ (strength=33%, prominence score=1.7), ‘travel’ (strength=33%, prominence score=1.6), ‘information’ (strength=31%, prominence score=1.6), ‘factors’ (strength=30%, prominence score=1.5), ‘negative’ (strength=28%, prominence score=1.4), and ‘content’ (strength=26%, prominence score=1.3) could be considered as the most important concepts within 39 research papers published from 2010 to 2014. Research papers in this first phase tended to investigate factors and sentiment analysis of reviews in the management sector in the travel industry. By contrast, in phase 2 from 2015 to 2020, the concepts highly scored on the strength, such as ‘model’ (strength=96%, prominence score=1.2), ‘data’ (strength=89%, prominence score=1.1), ‘managers’ (strength=88%, prominence score=1.1), ‘TripAdvisor’ (strength=88%, prominence score=1.1), ‘paper’ (strength=87%, prominence score=1.1), and ‘findings’ (strength=87%, prominence score=1.1) could be considered as the most important concepts by 126 research papers published from 2015 to 2020. Interestingly, it appeared that research papers in this phase tended to use a specific model to analyze data collected from current popular social

media applications and identify a specific social media application used in their studies.

Table 7: Top 15 ranked concepts for each year phase

This literature review technique could allow authors to seek the value of emerging research in social media in the hospitality sector. It might be useful to make a future research agenda in this area.

In seeking further wide publications in high-ranking journals, journals in diverse fields and subject categories, not only within the hospitality field, but also tourism, events, marketing, media, leisure, information management, and sociology fields can be targeted. Doing so requires that researchers explore this topic whilst crossing disciplinary boundaries. Multiple research concepts, across diverse subject categories, are more likely to give a greater opportunity for the critical development of the research of social media in the hospitality sector, and collaboratively influence the growth of the relevant industries.

Although various theories, models, frameworks, and/or approaches have been utilized in several papers in this topic, around 40 % of papers did not evidently apply or mention a theoretical base. It might be partly explained that there are a number of exploratory studies which adopted thematic analysis and thus failed to adopt a theoretical viewpoint. This links with the prior ‘newness’ of the concept of social media, and its emergence in the industry where its usage requires identification prior to quantification. Indeed, this is reflected in this study’s distinction of phases and cumulative publication totals which suggest a maturing scholarship. The examination of research topics may be explained in a different way with other theoretical frameworks. It was indicated that application of appropriate theories tends to lead to substantial outcomes with respect to specific phenomenon.

Thus, a lack of engagement with theory in the reviewed research papers on this topic presents an opportunity for future research to extend a further understanding of social media in the hospitality sector. Research informed by various relevant theories would be better able to provide scholarly direction and enhance research design.

Our results showed that quantitative analysis (64.8%) was used extensively in the analysis of social media contents, consistent with the prevalence of quantitative research found in previous hospitality and tourism studies on social media trends (Lu et al., 2018). Employing the quantitative content analysis approach have been suggested as a logical assessment of social media content to eliminate researcher bias, however it tends to limit explanatory value within the theoretical discussion (Riffe et al., 2019). According to Khang et al. (2012), qualitative methods undertake to offer greater understanding of a phenomenon, and lead to new insights into social media. A balance of these methodological approaches is therefore encouraged for social media researchers in hospitality to contribute uncovered theoretical directions forward. The continued use of mixed-methods approaches could likewise assist here.

Interestingly, the data in phase 1, from 2010 to 2014, showed that the sentiment analysis in the management sector in the travel industry has been focused. The sentiment analysis of users’ comments has long been a research focus in the fields of information science and technology and commercial marketing management, as well as in online customer reviews. With textual information mining, the analysis of reviews could offer insight into customer needs, improve business processes and help companies establish themselves in the market. Better decision-making for consumers, companies, and other stakeholders would also increase customer satisfaction (Lin et al., 2021). Therefore, the use of text sentiment analysis methods is still an important analytical approach for online review data. However, it is essential to point out that online review data has flooded with major hospitality websites and social media nowadays, therefore, the researchers would need to consider how to effectively form the relevant methods and technologies for capturing and analyzing the important data resources for sentiment analysis. The data in phase 2, from 2015 to 2020, revealed an increasing pattern of research examining the effects of social media, based on a specific model to analyze data from a popular social media application (e.g., TripAdvisor, Facebook). This trend indicates that scholars have recognized and responded to a heightened level of complexity to understanding in the scholarship. Given considerable, and rapid, increases in volumes of available social media data, exploration of complex aspects such as the subjectivity of text reviews and various features in the dataset are required (Jimenez-Marquez et al., 2019) as is the application of a comprehensive model or framework for the advancement of research in this area (Lamest & Brady, 2019). It is also evident why more researchers tend to focus on one major social media application for in-depth investigation than before, thus providing a glimpse into how social media research in hospitality has evolved through these phases.

The studies encapsulated in this review were highly skewed toward the hotel sector. Further, review articles encapsulated in this systematic review such as Kasavana et al.’s (2010) investigation, which aimed to serve as a genesis paper on social media use in the hospitality sector, found use of social media was prominent among hotels. Hotels were again the focus of a review of social media in the hospitality sector with Cantallops & Salvi’s (2014) review of eWOM. Schuckert and colleagues (2015) sought to review trends of online reviews within the wider hospitality and tourism industries and found 60% of their sample literature focused on hotels. Hotels were overwhelmingly the focus of Aydin’s (2020) review of social media use in the hospitality industry, which focused on Turkish facilities, where over 80% of the sample social media accounts were from hotels. Therefore, hotels very much appear the focus of social media investigations within the hospitality of tourism industry, which is also reflected in this systematic review.

It could be explained, as the ubiquity of hotels in social media research within the hospitality industry, that even studies which did not take a deliberate view toward hotels, such as Buhalis & Sinarta (2019) who investigated real time social media use within tourism and hospitality, still investigated hotels within the wider sample. This was also true of Kandampully et al.’s (2018) review of customer experience management within hospitality, where hotels still featured, though not as the dominant focus. Indeed, for studies not to evidently focus on hotels required highly focused investigations, such as Mkono & Tribe’s (2017) study which adopted a netnographic approach from the consumer perspective and served to categorize the behaviors of social media users in the hospitality and tourism industry; likewise, the study by Ladkin & Buhalis (2016) who investigated social media as a recruitment tool in the hospitality industry was highly focused in its research aim.

Although there is a clear need for the hotel sector to be reflected in social media research within the hospitality industry, given its overwhelming presence, it would be advantageous for other sectors within the industry to be more prominently featured. Also, it may be interesting for future investigation to extend to various social media applications, beyond TripAdvisor and Facebook. The popularity of different applications likely varies in each country, and indeed, over time. This call should be heeded by scholars and practitioners to widen the focus of social media application across the breadth of hospitality industry. Such research is, however, dependent upon industry shifts, (especially in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic), and to see how the hospitality industry has adapted its social media use heading toward the upcoming decade.

Presented in Figure 3 are the future research areas on social media in the hospitality based on the discussion of this study.

Figure 3: Future research on social media in the hospitality

CONCLUSIONS AND LIMITATIONS

The systematic review has presented the current status of the literature on social media in the hospitality sector. This paper reviewed and found that (1) research interest has increased rapidly over the last half decade in A-ranked journals in the field of hospitality; (2) one dominant theoretical approach (eWOM) has been used and about 40% of the published research papers are not clearly on the basis of the theoretical framework; (3) quantitative research methods have been mostly used to analyze contents data; and (4) there are more opportunities to investigate a diverse range of industry sectors and specific social media applications from various research perspectives. This quantitative systematic review contributes to gain insight into existing hospitality studies on social media, identify several research gaps, and provide future scholarly endeavors to develop a more strategic research agenda that encourages a more collaborative and various approach with the aim of better understanding social media research within the hospitality industry. It is important to consider that this review has demonstrated the existence of two clear phases of scholarship on social media use in the hospitality sector between 2010 and 2020. This distinction was identifiable because this review specifically adopted a hybrid review approach to the systematic review and was thus able to map and explain the trends within scholarship. Dissimilar from extant reviews, the current study’s utilization of Leximancer enabled the authors scope for narrative explanation and informed commentary on the scholarship’s current and future trends. Significantly, this enabled this study to comment on the apparent shifting focus of the literature toward the end of the decade toward maturity demonstrated by heightened focus on employing and discussing models.

Limitations of this study include its scope, of ten years between 2010-2020, and though this was necessitated by the research design as to investigate this specific period of research, the investigation period is of specific importance to the hospitality industry as it predates the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has significantly impacted on the hospitality industry through the various restrictions on events, travel, and venues. Hence, there are likely trends among the utilization of social media within the hospitality industry which have emerged as a result of, or in response to, the pandemic.

REFERENCES

industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(1), 1-21.https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1588824

55(4), 365-375.https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965514533419

36(5), 563-582.https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1592059

36 , 41-51.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.007

media websites?. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(4), 345-368.https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.571571

66, 53-61.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.018

1(1), 68-82.https://doi.org/10.1108/17579881011023025

30(1-2), 3-22.https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.750919

55(4), 523-536.https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514559033

positioning. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1133-1143.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.02.010

neural network analysis. Tourism Management, 50, 130-141.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.028

Marketing, 32(59), 608-621.https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.933154

review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207-222.https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

22(2), 117-128.https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011024246

e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 634-639.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.014 Yen, C.-L. A., & Tang, C.-H. H. (2015). Hotel attribute performance, eWOM motivations, and media choice. International Journal of Hospitality

Please cite this article as: