INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents a major global health challenge, ranking as the third most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates, CRC accounts for approximately 10 % of new cancer cases and 9.4 % of cancer-related deaths annually (1). The progressive accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations in colonic epithelial cells contributes to malignant transformation and tumour progression (2). Numerous modifiable risk factors, including obesity, low physical activity, high consumption of red and processed meat, smoking, alcohol intake, and inflammatory bowel disease, have been linked to increased CRC risk (3–7). Despite advances in surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapies, colorectal cancer remains a major therapeutic challenge, particularly in advanced stages where treatment resistance and insufficient screening reduce overall efficacy (8–11). Resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and the inability to selectively target tumour cells remain major barriers to successful treatment, especially in metastatic CRC (12–14).

The increasing use of plant-derived compounds in both traditional and complementary medicine has drawn considerable scientific interest. In addition to their conventional use in primary healthcare, phytochemicals are gaining popularity in developed countries under the label of health supplements (15–17). These bioactive molecules exhibit chemopreventive properties through antioxidant activity, inhibition of inflammation, epigenetic regulation, and modulation of apoptosis-related signalling pathways (18–22).

Lavandula stoechas L. (Lamiaceae), commonly known as “karabaş otu” in Turkey, has been traditionally used in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions to alleviate respiratory and gastrointestinal ailments and is frequently consumed as an herbal infusion (23–26). Its therapeutic applications are thought to arise from its rich phytochemical composition, including rosmarinic acid, linalool and camphor, which exhibit documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (27). Recent studies have further demonstrated that L. stoechas extracts suppress cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in several cancer cell lines by modulating the expression of the BAX/BCL-2 signalling axis (28, 29). These findings highlight its emerging role as a candidate anticancer agent. However, despite such evidence, the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of L. stoechas in colorectal cancer have not yet been clearly elucidated.

Dysregulation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, primarily involving the mitochondrial regulators BAX and BCL-2, the upstream tumour suppressor TP53, and the executioner enzyme caspase-3, contributes to colorectal tumorigenesis by impairing programmed cell death mechanisms (30). Given the central roles of these genes in CRC pathophysiology, targeting molecular pathways involving TP53, BAX, BCL-2, and CASP3 may provide a mechanistic rationale for the development of plant-derived anticancer therapeutics. Investigating the effects of natural compounds on the expression of these genes may offer new insights into potential therapeutic mechanisms. Despite its traditional use and reported pharmacological effects, there is currently limited evidence on the molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer activity of L. stoechas, particularly in colorectal cancer. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by evaluating its effects on key regulatory genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis.

The present study aims to evaluate the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic potential of Lavandula stoechas L. flower ethanolic extract (LsHE) on HT-29 colorectal cancer cells, while also assessing cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and gene expression in both HT-29 and HEK-293 cells, as well as characterising the extract’s phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cells and chemicals

The human cell lines, HT-29 colorectal cancer cells and HEK-293 healthy epithelial cells, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA).

DMEM (Gibco, USA), fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA, PBS and trypan blue (all from Merck KGaA, Germany) were used for cell culture. Alamar blue reagent was obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (USA). The cDNA synthesis kit was purchased from Nepenthe (Turkey), and SYBR green master mix was obtained from Roche (Germany). The FITC Annexin V apoptosis detection kit was obtained from Nepenthe. Gallic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, epicatechin, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, salicylic acid, rutin hydrate, rosmarinic acid, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, cinnamic acid, quercetin, and naringenin (all HPLC grade, Merck) were used as standards. Methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid (all HPLC grade, Merck) were used for chromatographic analyses. Deionised water was prepared using a Milli-Q purification system (Merck).

Plant material and extract preparation

L. stoechas L. species were randomly collected from a field located at approximately 500 meters above sea level in Koçarlı district of Aydın province, Turkey, in June 2020. The botanical identification was performed, and the authenticated voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Istanbul University (voucher no. ISTE-118356).

The dried and vacuum-packed flowering tops of L. stoechas L. were ground using a laboratory-scale knife mill, operated intermittently to avoid overheating. The resulting powdered material was extracted at a ratio of 1:10 (m/V) in a 70:30 (V/V) ethanol-water mixture by maceration at 25 ± 2 °C for 24 hours. After filtration, the solvent was removed from the extract using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph Rotary Evaporator with WB eco bath, Germany). Afterwards, the extract was frozen at −80 °C and lyophilised (LaboGene ScanVac Coolsafe 110-4, Denmark) to obtain the crude extract. Prepared samples were stored at −18 °C until analysis. The extraction yield of LsHE was determined to be 12 % (m/m), based on the dry mass of the initial plant material. To ensure efficient extraction of phenolic compounds, an ethanol-water solvent system was employed, as such mixtures might enhance the yield of bioactive polyphenols compared to single-solvent extractions (31, 32).

Phytochemical characterization

Total phenolic contents . – The total phenolic content of the extract was determined using the colourimetric Folin-Ciocalteu method, which relies on the formation of blue-colored complexes between phenolic compounds and the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent in an alkaline medium, as described by Singleton and Rossi (33). Briefly, 0.5 mL of LsHE was mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (0.2 mol L–1, Merck), followed by the addition of 2.0 mL of sodium carbonate solution (75 g L⁻¹). The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 hours in the dark. Absorbance was then measured at 765 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry mass (dm) (mg GAE g–1).

Phenolic profile analyses. – The chromatographic method was adapted from previously validated literature sources (34, 35) and applied here for the phytochemical screening of LsHE. A quantitative analysis was performed using a Shimadzu Nexera-i LC-2040C 3D Plus high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. A photodiode array detector (PDA) set at 254 nm was used for detection. Chromatographic separation was performed using a phenylhexyl reversed-phase column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3 µm particle size; GL Sciences InterSustain, Japan). The mobile phase comprised solvent A: 0.1 % formic acid in deionised water, and solvent B: acetonitrile (HPLC grade), used in accordance with the gradient elution protocol outlined in Table SI (Supplementary material), adapted from previously validated methods (34, 35). The flow rate was sustained at 1.0 mL min–1, and the injection volume for both standards and samples was 10 µL. The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C during the study.

For each compound to be identified, the wavelength corresponding to maximum absorbance (λmax) was determined, and subsequent quantification was performed at the respective wavelength. Calibration curves were constructed for each standard compound (Table I).

Table I. HPLC data for reference standards

aLOQ = 3×LOD

The analysis involved preparing the LsHE at a concentration of 1 mg mL–1 using the mobile phase, followed by analysis under the same chromatographic conditions (Table SI, Supplementary material). The concentrations of phenolic compounds detected in the extract are reported in mg mL–1 and, after calculation, given as mg g–1 extract. A representative chromatogram of 15 standard phenolic compounds used for calibration is shown in Fig. 1, where each peak corresponds to an individual compound detected at 254 nm.

Fig. 1. HPLC chromatogram of a mixture of 15 standard phenolic compounds detected at 254 nm. Peaks were identified by comparing their retention times with those of reference standards: 1 – gallic acid, 2 – 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3 – chlorogenic acid, 4 – vanillic acid, 5 – caffeic acid, 6 – epicatechin, 7 – p-coumaric acid, 8 – ferulic acid, 9 – salicylic acid, 10 – rutin, 11 – rosmarinic acid, 12 – apigenin-7-O-glucoside, 13 – cinnamic acid, 14 – quercetin, 15 – naringenin.

In this report, only partial model re-validation of the already known HPLC-DAD method (34, 35) was performed (36–38).

Quantification was performed using calibration curves generated for each compound. Coefficient of determination (R²) for the calibration lines ranged from 0.9920 to 0.9999 (Table I). Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated using the formulae LOD = 3.3σ/S and LOQ = 10σ/S, where σ represents the residual standard deviation of the regression line (based on five replicate measurements, n = 5) and S denotes the slope of the calibration curve.

Total antioxidant capacity. – The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of L. stoechas L. extract was determined using the phosphomolybdenum method described by Prieto et al. (39). Briefly, 0.1 mL of the extract (1 mg mL–1) was mixed with 1.0 mL of the reagent solution containing 0.6 mol L–1 sulfuric acid, 28 mmol L⁻¹ sodium phosphate (Na2HPO4 × 12 H2O) and 4 mmol L⁻¹ ammonium molybdate, in a test tube. The mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 90 minutes in a thermal block. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 695 nm. TAC values were calculated based on an ascorbic acid calibration curve and expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalents per gram of dry mass (mg AAE g–1).

Cell culture, treatment and viability assay

HT-29 colorectal carcinoma and HEK-293 epithelial cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mmol L⁻¹ L-glutamine, and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2. LsHE was dissolved in culture medium with 0.1 % (V/V) DMSO and applied to cells at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 300 µg mL–1 for 48 hours. Cells were treated with Alamar blue reagent (10 % of the total well volume) for 3 hours, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, following 48-hour exposure to increasing concentrations of LsHE (12.5–300 µg mL–1). Absorbance was measured at 570 nm and 610 nm using a microplate reader. The concentration of LsHE required to inhibit 50 % of cell viability was determined by fitting non-linear sigmoidal dose–response curves to the viability data plotted against the log-transformed concentrations of LsHE.

Two types of control groups were included in all experiments: negative control - untreated cells, maintained under standard culture conditions without any treatment; vehicle control – cells exposed to culture medium containing 0.1 % (V/V) DMSO, corresponding to the solvent concentration used for LsHE dissolution.

Apoptosis assay

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from HT-29 cells using the total RNA extraction kit (Nepenthe), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quantity and purity were evaluated with a NanoDropTM spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), and samples with A260/280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.1 were used for downstream analyses.

cDNA was synthesised using the cDNA synthesis kit (Nepenthe), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The thermal conditions for reverse transcription were as follows: 25 °C for 5 minutes, 46 °C for 20 minutes, 95 °C for 1 minute, and held at 4 °C. Primer sequences for BAX, BCL-2, TP53, CASP3 and GAPDH are listed in Table II. GAPDH served as the reference gene.

Table II. Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR was performed using the QuantstudioTM 7 real-time PCR detection system (Thermo, USA). Each 10-μL reaction mixture contained 5 μL of SYBR Green master mix (Qiagen, Germany), 2 μL of diluted cDNA (10 ng µL–1), 1 μL of each primer mix (10 µmol L–1), and 2 μL of nuclease-free water. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial activation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s and combined annealing/extension at 60 °C for 10 s according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer specificity was verified by melting curve analysis. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Gene expression was analysed using the 2^–ΔΔCt method.

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparisons. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phenolic compounds

Total phenolics. – The total phenolic content (TPC) of the LsHE, calculated from the gallic acid calibration curve (y = 0.0082x + 0.0208, R² = 0.988), was determined as 230.31 ± 11.28 mg GAE g–1 dm. This value is markedly higher than that reported by Celep et al. (40), who recorded 81.58 ± 3.66 mg GAE >g–1 dm in the dry extract obtained from the aerial parts of L. stoechas ssp. stoechas, using 80 % methanol as the extraction solvent. Similarly, aqueous-EtOH extracts (1:1, V/V) of Lavandula angustifolia from Romania, likely prepared from aerial parts, yielded a significantly lower TPC of 50.6 ± 3.2 mg GAE g–1, highlighting the influence of species and extraction protocol on polyphenol recovery (41). In contrast, Karabagias et al. (42) reported a TPC of 217 mg GAE L–1 for the methanolic extract and 4289 mg GAE L–1 for the aqueous extract of L. stoechas flowers. Discrepancies across the studies, despite often contradictory, emphasise that phenolic recovery is influenced by multiple factors, including solvent polarity, the species/plant part used, species-specific phenolic profiles, extraction temperature and time.

The complexity of the issue of flavonoids' solubility also includes structural/mechanistic features of flavonoids and inter/intramolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, delocalisation, structure/planarity, functional groups) (43). Generally, poor solubility of flavonoids in water compared to organic solvents like methanol or acetone, underscores the central role of solvent-solute interactions in extraction efficiency. Flavonoids typically display low aqueous solubility due to their hydrophobic aromatic backbone, whereas organic solvents such as ethanol can establish stronger hydrogen-bonding and π–π interactions, thereby enhancing solubilization and facilitating higher recovery yields.

Individual phenolic composition. – It was analysed in LsHE using HPLC-DAD, and the chromatograms revealed distinct peaks corresponding to various phenolic acids and flavonoids (Fig. 2). The detailed quantification results are presented in Table III. Among the detected compounds, rosmarinic acid exhibited the highest concentration (526.762 mg g–1 dm), followed by quercetin (215.335 mg g–1 dm), confirming their predominance in the extract. These findings are consistent with those of Karabagias et al. (42), who reported the presence of caffeic acid, quercetin-O-glucoside, luteolin-O-glucuronide and rosmarinic acid in L. stoechas, contributing to its strong antioxidant capacity.

Fig. 2. Overlay chromatogram of the LsHE and the phenolic standards used for the qualitative identification of phenolic compounds in the LsHE.

Table III. Phenolic compounds in LsHE extract

| Compound | Concentration (mg L–1) | Amount in dry plant (mg g–1 dm) |

|---|---|---|

| Caffeic acid | < LOD | – |

| Chlorogenic acid | < LOD | – |

| Ferulic acid | < LOD | – |

| Quercetin | LOD < 1.786 < LOQ | 215.335 |

| Rosmarinic acid | 4.369 | 526.762 |

| Rutin | < LOD | – |

Rosmarinic acid (RA) has been extensively studied for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic effects. For instance, it significantly inhibited the proliferation of WiDr colon cancer cells by modulating apoptosis-related genes, including downregulation of BCL-2 and upregulation of caspase-1 and -7 (44). Lu et al. (45) further demonstrated that RA scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhances endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT via activation of the Nrf2 pathway. Likewise, Jang et al. (46) reported that RA induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells through the mitochondrial pathway by upregulating Bax and caspase-3, and downregulating HDAC2 and BCL-2.

Quercetin, the second most abundant compound in LsHE, has also been documented to possess multiple biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic effects. It has been shown to inhibit the viability of colon cancer cells (CT26, MC38, Caco-2, SW620) by modulating apoptotic pathways, including downregulation of BCL-2 and upregulation of Bax expression (47, 48). Moreover, Han et al. (49) reported that quercetin decreases pro-inflammatory markers such as TNF-α, IL-6, and COX-2 through inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB signalling cascade.

For ferulic, caffeic and chlorogenic acids, as well as rutin, detectable signals were observed; still, their concentrations were below the calculated LOD values.

TAC analysis. – Based on the ascorbic acid calibration curve (y = 3.956x – 0.0227, R² = 0.988), the total antioxidant capacity of the LsHE was measured as 0.1218 ± 0.0075 mg AAE g–1 dm. Compared to that, Celep et al. (40) reported 67.07 ± 3.79 mg AAE g–1 dm for the 80 % methanolic extract of L. stoechas, prepared from the aerial parts, using the same assay. Similarly, a study conducted by Ezzobi et al. (50) reported that the total antioxidant capacity of a 4:1 (V/V) ethanol–water extract obtained from the aerial parts of L. stoechas, collected from Morocco, was 255.5 µg mL–1 AAE, as determined by the phosphomolybdenum method. These variations in antioxidant capacity among studies can be attributed to differences in extraction solvents and the geographical origin of plant materials; nevertheless, the consistent use of aqueous ethanolic systems and similar analytical methods highlights the overall high antioxidant potential of L. stoechas extracts.

Cytotoxicity

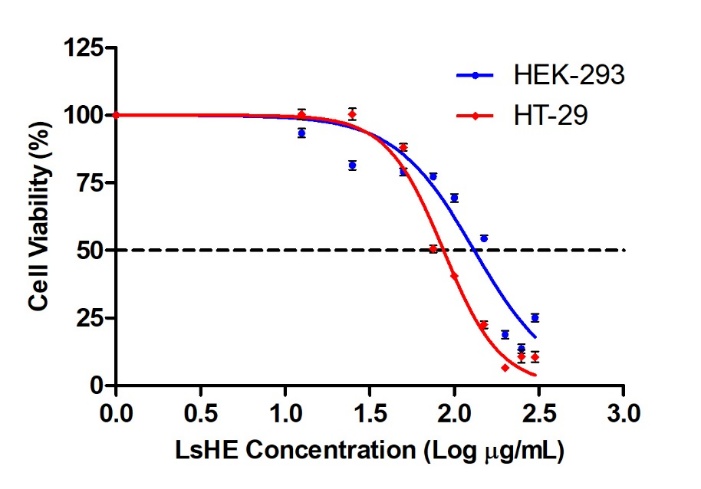

The antiproliferative effects of the LsHE were evaluated on HT-29 colorectal cancer cells and HEK-293 normal epithelial cells using the Alamar blue assay. Based on the nonlinear regression analysis of the dose–response curve (Fig. 3), the concentration of LsHE required to inhibit 50 % of cell viability was determined as 86.37 ± 3.07 µg mL–1 for HT-29 cells and 131.30 ± 9.33 µg mL–1 for HEK-293 cells, yielding a selectivity index (SI) of approximately 1.5.

Fig. 3. Cytotoxic effects of LsHE on HT-29 and HEK-293 cells. Dose-response curves were generated to determine the LsHE concentration required to inhibit 50 % of cell viability. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

The observed cytotoxicity of LsHE on HT-29 cells is in line with previous studies reporting the antiproliferative effects of L. stoechas extracts on different cancer cell lines. For instance, the essential oil of L. stoechas exhibited potent cytotoxic activity against the COL-22 colon cancer cell line, with an ED₅₀ value of 9.8 µg mL–1, which may be attributed to the higher lipophilicity and greater concentration of volatile bioactives in essential oils compared to polar solvent-based extracts (24). Similarly, Bouyahya et al. (51) reported that an ethanolic extract of L. stoechas, prepared from the aerial parts, showed significant cytotoxicity on the human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cell line, with an IC50 of 19.03 ± 2.05 µg mL–1. Although RD is a different cancer model, the similarity in the extraction method supports the relevance of solvent-dependent activity. In contrast, a methanolic extract of L. stoechas, prepared from the aerial parts of Lesvos island, exhibited low cytotoxicity on Caco-2 colon cancer cells, with LC50 values exceeding 75 µg mL–1 (52). Furthermore, an ethanolic extract prepared from the aerial parts of L. stoechas was reported to exhibit weak cytotoxicity against HepG2 liver cancer cells, with concentrations required to inhibit 50 % of cell viability ranging from 1000 to 1500 µg mL–1 (53). This discrepancy may be attributed to several factors, including the plant part used (aerial parts vs. flowers), the extraction model and the cancer cell line tested. The comparatively stronger effect observed in our study may result from the higher phenolic content of the flower-derived LsHE extract, particularly its enrichment in rosmarinic acid and quercetin.

The observed activity may be partially attributed to the major phenolics in LsHE, namely, rosmarinic acid and quercetin. Rosmarinic acid has been shown to induce apoptosis in WiDr colon cancer cells (44), while quercetin exerts dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on several colorectal cell lines such as CT26, Caco-2 and SW620 (47, 48). Phenolic hydroxyl groups of these compounds are believed to contribute to their anticancer activity through hydrogen bonding and redox interactions with DNA and apoptosis-related proteins (54, 55). Overall, the moderate cytotoxicity, observed in this study may arise from the synergistic activity of these constituents. The distinct difference of concentration for 50 % inhibition between normal and cancerous cells further supports the therapeutic promise of LsHE in colorectal cancer management.

Apoptosis/necrosis – Gene expression analysis

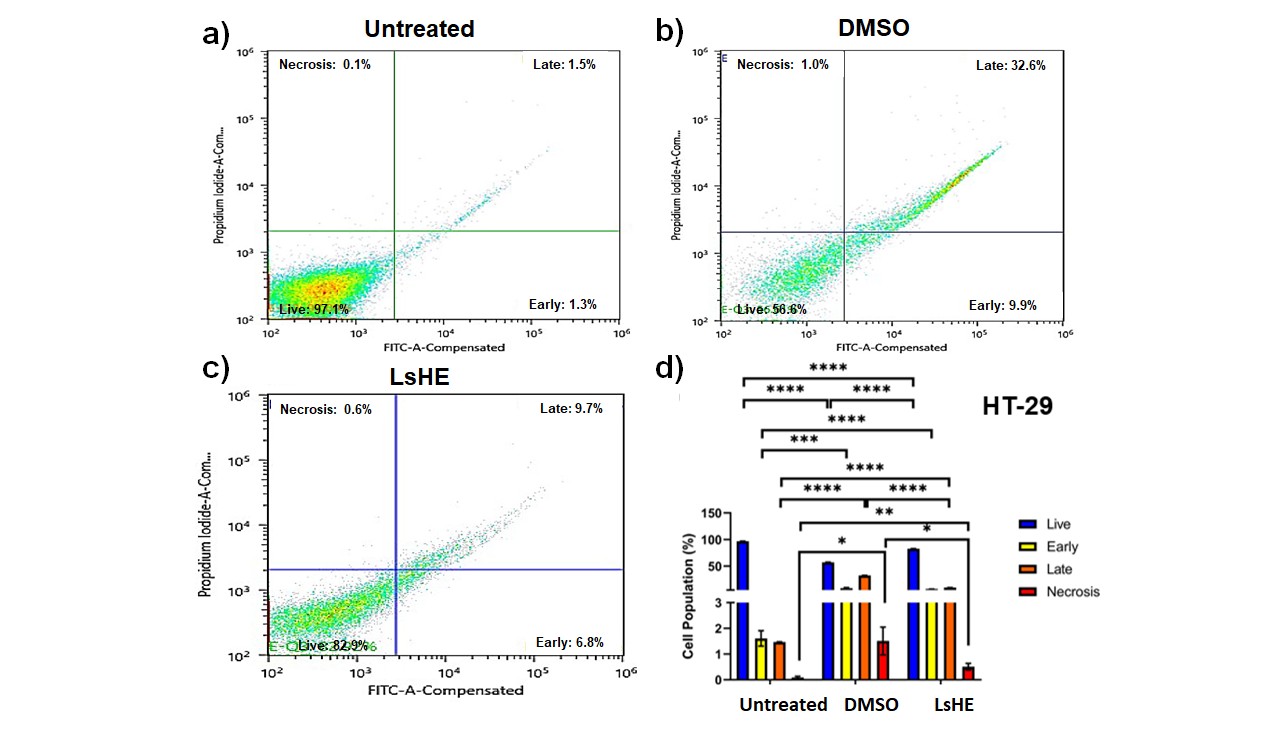

To determine the pro-apoptotic potential of LsHE, Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining was conducted on HT-29 and HEK-293 cells. In HT-29 cells, treatment with LsHE significantly increased both early and late apoptotic populations compared to the untreated group. Specifically, early apoptosis increased from 1.5 to 9.7 % (p < 0.0001), and late apoptosis rose from 1.3 to 6.8 % (p < 0.0001). These changes were accompanied by a reduction in live cells from 97.1 to 82.9 % (p < 0.0001) and a slight but statistically significant increase in necrotic cells from 0.1 to 0.6 % (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). These results indicate that LsHE induces a shift from viability toward programmed cell death in HT-29 cells through apoptotic rather than necrotic mechanisms.

Fig. 4. Apoptosis analysis of HT-29 cells treated with LsHE for 48 h. Representative dot plots of Annexin V-FITC/PI staining obtained by flow cytometry in: a) untreated; b) DMSO; c) LsHE-treated groups; d) bar graph showing the distribution of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells (%). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Comparisons were performed among all groups within each cell population subtype (i.e., untreated vs. DMSO, untreated vs. LsHE, and DMSO vs. LsHE) for each cell population subtype (live, early, late, necrosis). Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

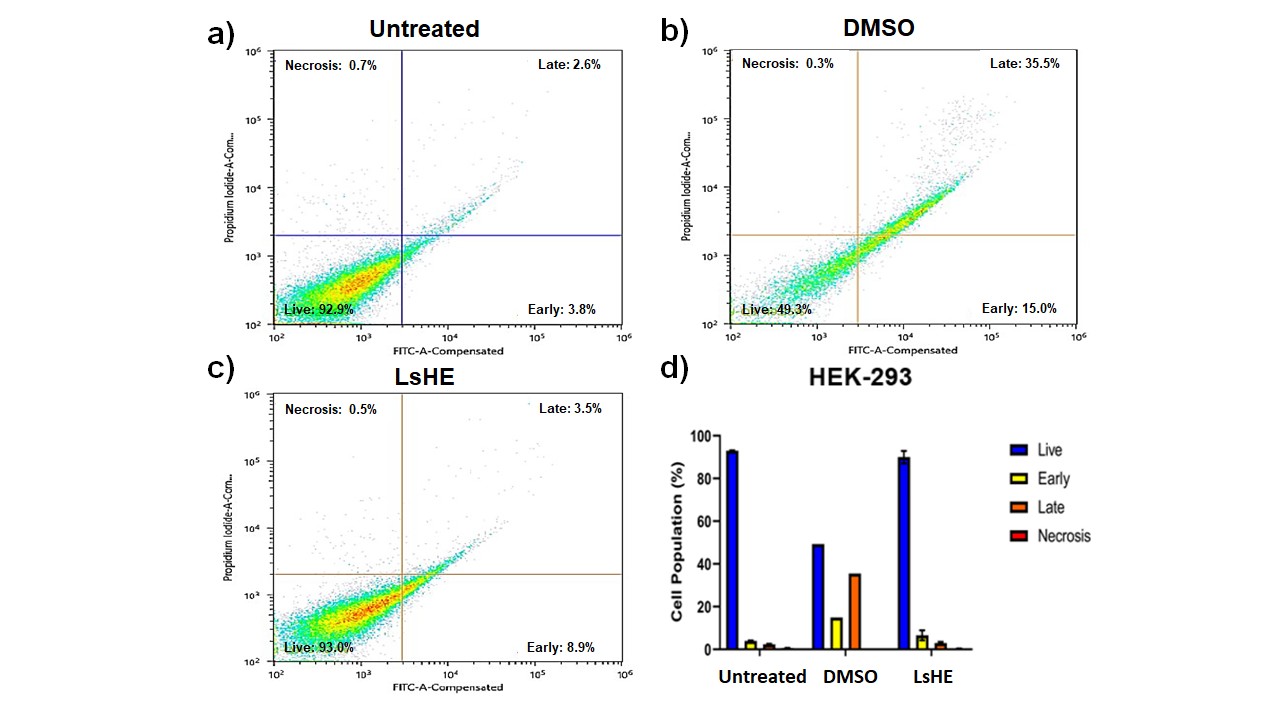

Similarly, in HEK-293 cells, LsHE induced a robust early apoptotic response (35.5 %) and elevated late apoptosis (15.0 %), accompanied by decline in viable cells from 88.2 to 82.3 % (Fig. 5). These findings indicate that LsHE promotes apoptosis in both cancerous and non-cancerous cells, with a more pronounced and statistically validated effect in HT-29 cells.

Fig. 5. Apoptosis analysis of HEK-293 cells treated with LsHE for 48 h. Representative dot plots of Annexin V-FITC/PI staining obtained by flow cytometry in: a) untreated; b) DMSO; c) LsHE-treated groups; d) bar graph showing the distribution of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells (%). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

In parallel, qRT-PCR analyses were conducted to assess the expression of apoptosis- and inflammation-related genes, including BAX, BCL-2, CASP3 and TP53 (Fig. 6). BAX, a key pro-apoptotic gene in the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, was significantly downregulated in both HEK-293 and HT-29 cells following LsHE treatment. In HEK-293 cells, LsHE administration led to a moderate but statistically significant reduction in BAX expression compared to the untreated group (p < 0.05). Similarly, in HT-29 cells, BAX expression was markedly suppressed after treatment with LsHE (p < 0.001), indicating a potential reduction in apoptotic signalling (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Effect of LsHE on apoptotic gene expression in HEK-293 and HT-29 cells. Relative mRNA expression levels of pro-apoptotic BAX (a, e), anti-apoptotic BCL2 (b, f), CASP3 (c, g), and tumor suppressor TP53 (d, h) were assessed by qRT-PCR in HEK-293 (a–d) and HT-29 (e–h) cells after 48 h of treatment with LsHE. Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5). Significantly different vs. respective controls (untreated and DMSO): *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In both cell lines, LsHE treatment significantly upregulated the expression of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 gene. In HEK-293 cells, BCL-2 mRNA levels were significantly elevated compared to untreated group (p < 0.05). A similar trend was observed in HT-29 colorectal cancer cells, where BCL-2 expression was higher than in untreated group but not significantly (Fig. 6).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that LsHE treatment significantly upregulated CASP3 expression in both HEK-293 and HT-29 cells when compared to untreated group. In both cell lines, LsHE induced a significant increase in CASP3 mRNA levels relative to untreated group (p < 0.01), indicating a potential activation of caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling (Fig. 6), suggesting that caspase-3-dependent apoptosis is a key mechanism underlying LsHE-induced cytotoxicity in both cell types.

The BCL-2 family of proteins plays a central role in the regulation of apoptosis and is critically implicated in CRC initiation, progression, and resistance to therapy. Among the BCL-2 family proteins, anti-apoptotic members such as BCL-2 and pro-apoptotic effectors such as BAX and BAK play pivotal roles in the regulation of mitochondrial apoptosis through their interactions at the outer mitochondrial membrane (56). The pro-apoptotic proteins BAX and BAK initiate mitochondrial apoptosis by increasing outer membrane permeability, which in turn triggers the activation of the caspase cascade (57). Caspase-3, a key executioner caspase, is activated by upstream initiator caspases (caspase-8, -9, or -10) in both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, ultimately driving the cleavage of cellular substrates and apoptotic cell death (58). TP53, encoding the tumor suppressor p53, serves as a major regulator of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to stress. In CRC, TP53 is mutated in approximately 43 % of cases, highlighting its clinical relevance (59, 60). p53 promotes mitochondrial apoptosis through both transcription-dependent activation of pro-apoptotic genes like BAX and repression of anti-apoptotic genes like BCL-2, as well as transcription-independent interactions with BAX, BAK and BCL-2 at the mitochondria (61).

Numerous studies investigating Lavandula species and other medicinal plant extracts have reported pro-apoptotic gene expression profiles in various cancer models, including HT-29 cells. These studies commonly demonstrate upregulation of BAX, TP53 and CASP3, accompanied by downregulation of BCL-2, following treatment with plant-derived compounds (62–66).

In contrast, our study revealed a distinct expression pattern. Treatment with LsHE significantly downregulated BAX expression in both HEK-293 (p < 0.05) and HT-29 (p < 0.001) cells. Meanwhile, BCL-2 expression was significantly upregulated in HEK-293 cells (p < 0.05), and a similar trend was observed in HT-29 cells, although it was not statistically significant. Despite these observations, CASP3 expression was significantly increased in both cell lines (p < 0.01), suggesting the activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways. Additionally, LsHE treatment led to a significant increase in TP53 mRNA levels in HT-29 cells (p < 0.05), with a moderate elevation also observed in HEK-293 cells.

These results differ from many previous studies, in which increased BAX and decreased BCL-2 expression are typically observed in response to plant-based treatments (65, 66). Interestingly, our findings are consistent with a recent study by Kadkhoda et al. (67), who reported similar gene expression dynamics and suggested that the anticancer effects of plant extracts may vary depending on concentration and phytochemical composition.

One possible explanation for the observed gene expression profile is the differential regulation within the BCL-2 family. Although BAK expression was not directly assessed in this study, it has been reported that anti-apoptotic proteins do not equally inhibit all pro-apoptotic members; specifically, BCL-2 fails to inhibit BAK effectively (68). This differential regulation suggests that LsHE may trigger apoptosis via a BAK-dependent pathway, potentially bypassing the need for BAX activation. The upregulation of TP53 and CASP3, despite the downregulation of BAX, suggests that p53-mediated, caspase-3-dependent apoptosis is a dominant mechanism in LsHE-treated HT-29 cells.

These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that various plant-derived products, including Lavandula extracts and phenolic constituents such as rosmarinic acid, promote apoptosis in various cancer cell lines, including HT-29 colorectal, MCF-7, and SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells, by activating the p53 pathway and caspase-3 expression (62–64, 66). It is also plausible that cytoplasmic p53 contributed to apoptosis in our study via transcription-independent mechanisms, such as direct interaction with mitochondrial proteins (61).

Flow cytometry results further support these findings, confirming an increase in apoptotic cell populations following LsHE treatment. Taken together, these results indicate that LsHE may trigger apoptosis through alternative molecular pathways that are independent of BCL-2 and BAX regulation but dependent on TP53 and CASP3 activation.

These results are in agreement with previous studies on L. stoechas and its bioactive components, which have been shown to trigger apoptosis through similar mechanisms. For instance, Rasheed et al. (29) demonstrated that oleanolic acid isolated from L. stoechas significantly induced apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, as evidenced by increased early and late apoptotic cell populations detected by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. This effect was further supported by the upregulation of BAX, TP53 and CASP3, along with downregulation of BCL-2, indicating mitochondrial pathway involvement. In another study, Tayarani-Najaran et al. (69) reported that methanolic L. stoechas extract protected PC12 neuronal cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by downregulating pro-apoptotic markers and upregulating BCL-2, highlighting the context-dependent dual behaviour of L. stoechas in promoting or preventing apoptosis depending on the cell type and physiological condition.

In light of these findings, our results suggest that LsHE exerts a pronounced pro-apoptotic effect in HT-29 colorectal cancer cells, as shown by the significant increase in early and late apoptotic populations and elevated CASP3 and TP53 expression. These data support the idea that LsHE may activate caspase-dependent apoptosis, possibly via a p53-mediated pathway, even in the absence of BAX upregulation, further reinforcing the mechanistic versatility of Lavandula-derived phytochemicals in cancer models.

Limitations of the study

Limitations of the present study include the relatively low selectivity index of LsHE and the incomplete chemical characterisation of LsHE, as several peaks still remained unidentified.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that LsHE exerts promising antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on HT-29 human colorectal cancer cells. Phytochemical analysis revealed high levels of phenolic compounds, particularly rosmarinic acid and quercetin, which likely contribute to the observed bioactivity. LsHE-induced apoptosis was confirmed by Annexin V/PI staining and upregulation of TP53 and CASP3 gene expression. Interestingly, the concurrent downregulation of BAX suggests that LsHE may trigger apoptosis via alternative pathways, independent of the classical BAX/BCL-2 axis.

The present findings offer valuable mechanistic insight into the anticancer potential of L. stoechas and support its further evaluation as a candidate for phytochemical-based adjunctive therapy in colorectal cancer. To strengthen the translational relevance of these findings, future studies should address current limitations by confirming gene-level changes at the protein level and validating efficacy through in vivo experiments.

Supplementary material is available upon request.

Abbreviations, acronyms, symbols. – AAE – ascorbic acid equivalent, ATCC – American Type Culture Collection, BAX – Bcl-2-associated X protein, BCL-2 – B-cell lymphoma 2, CASP3 – caspase-3, DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide, dm – dry mass, DMEM – Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium, FBS – fetal bovine serum, GAE – gallic acid equivalent, GAPDH – glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, LOD/LOQ – limit of detection/quantification, PBS – phosphate-buffered saline, PI – propidium iodide, RA – rosmarinic acid, SI – selectivity index, TAC – total antioxidant capacity, TP53 – tumor protein p53.

Acknowledgements. – The authors are thankful to Assoc. Prof. Dr. İlker Genç (Faculty of Pharmacy, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey) for the botanical identification of the plant material. The authors also acknowledge Prof. Dr Hüsamettin Vatansever (Department of Medical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey) for his support in the procurement of cell cultures. This research was supported by the University of Health Sciences research foundation.

Conflicts of interest. – The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding. – This research was funded by the University of Health Sciences research foundation under Grant (2021/115 and 2022/100).

Authors contributions. – Conceptualization, Z.D. and M.S.D.; methodology, Z.D., M.S.D., and Ö.K.; investigation, G.Y., M.E., and Ö.K.; data analysis, Z.D., M.S.D., G.Y., Ö.K., and M.E.; visualization, Z.D. and Ö.K.; writing-original draft preparation, Z.D. and M.S.D.; writing-review and editing, Z.D. and M.S.D.; supervision, Z.D. and M.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.