INTRODUCTION

Tourism experience has become the center of attention in the industry due to the highly competitive marketplace (Kim, 2018; Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2021). Recently, tourism research has turned to an extreme tourism experience in the form of dark tourism as a popular and niche product that has attracted interest in scientific spheres and practice (Light, 2017; Sharma & Nayak, 2019; Rajasekaram et al., 2022). Dark tourism draws millions of visitors annually, benefiting many groups, particularly local communities of the dark sites (Lewis et al., 2022; Lv et al., 2022). Among the popular sites associated with dark tourism are the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial, the 9/11 World Trade Centre site, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster sites and the Gallipoli War site of World War 1 (Martini & Buda, 2020). These dark tourism sites serve as a means for individuals to cope with death and dark life events (Prayag et al., 2021). Visitors reminisce about dark tourism sites to accommodate and cater for their emotional space apart from tourist attractions.

Tourists visit dark tourism sites due to natural reasons such as curiosity and excitement (Yan et al., 2016), knowledge (Mangwane et al., 2019), national identity (Farmaki, 2013), empathy and self-discovery (Isaac & Cakmak, 2014; Hartmann et al., 2018) and patriotism (Kang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2021a). The drive can also be within a darker pursuit, which includes morbid curiosity (Blom, 2000; Stone & Sharpley, 2008; Biran et al., 2014), bloodlust (Podoshen et al., 2018), schadenfreude (Seaton & Lennon, 2004) and voyeurism (Cole, 1999). These drives and motivations are all attributed to increasing dark tourism visitation (Kim & Barber, 2022). There is a lack of research and empirical support addressing tourist motivations to visit dark sites (Light, 2017; Lewis et al., 2022). Gaps in the dark tourism field are apparent due to its inherently distinct attractions compared to conventional tourism attractions. The attraction in dark tourism is related to thanatopsis as a contemplation of death, of which the understanding of the determinants for tourist visits to dark places is lacking. This study investigates the structural knowledge of dark tourism by performing science mapping techniques on this niche tourism area through cross-examination of the factors that lead tourists to visit dark places.

The study is motivated by two premises. First, dark tourism sites should be embraced as an opportunity for future generations to learn and acquire meaning to improve communities’ socio-economic development. Dark tourism sites are an important educational tool that contributes to education, specifically in curriculum theories (Israfilova & Khoo-Lattimore, 2019). Even though past scholars have conceptualized dark tourism as a significant educational measure, Biran et al. (2011) argued that

educational stances and motives for dark tourism are often ignored. Rather studies are interested in the mere death of significant dark sites. Apart from being a source of economic development for local communities, dark tourism is an educational tool for the locals to learn and grasp the importance of peace and harmony (Gibson et al., 2022). It reminds future generations that war and conflict would only lead to bloodshed and national destruction (Grinfelde & Veliverronena, 2021).

Secondly, although dark tourism literature has been gaining momentum within the wider scope of tourism products, a comprehensive and holistic review of the subject is lacking. Only a few reviews on dark tourism were significant concerning this current subject. Light (2017) reviewed dark tourism between 1996-2016, discovered six significant themes, and asserted that dark tourism and thanatourism are categorized under the sub-domain of heritage tourism. Rajasekaram et al. (2022) present a systematic literature review on the dark tourism experience through the theory-context-characteristics-methodology (TCCM) approach. The crucial finding shows a need for more understanding from the perspective of tourists’ experience within the spectrum of dark tourism and darker end. Iliev (2021) present a review based on the three concepts of consumption, motivation and dark tourism experience as a package. Findings suggest that tourists are driven by the desire to explore cultural heritage, education, learning and the attraction to understand the history of dark tourism sites. From the macro perspective of dark tourism, Bhowmik (2021) performed a bibliometric review of heritage tourism. Results revealed seven active clusters focusing on sustainable tourist activities, local communities’ perspectives and urban planning heritage. These past reviews on dark tourism have provided a fundamental understanding of the phenomenon in the tourism literature but have yet to uncover the knowledge structure of dark tourism. To the best of the author’s knowledge, Bhowmik’s (2021) study is the only one that applies bibliometric analysis on dark tourism but has only performed a co-citation analysis without presenting the current and future trends of dark tourism. This study fulfils this shortcoming by presenting a science mapping approach through bibliometric analysis by linking the intellectual structure of dark tourism. Hence to fill in the gaps and present state-of-the-art knowledge structure and science mapping on the subject, this study presents a bibliometric review based on the following objectives:

LITERATURE REVIEW

Travels linked to death and suffering go way back in history. The Roman gladiator games depict dark tourism in the early days. People traveled to watch people being killed for sport, guided tours to watch hanging prosecuted people, and pilgrimages to medieval execution sites (Lewis et al., 2022). Although it is recently gaining popularity, the concept was already in the picture of tourism since the late twentieth century (Light, 2017). The terminology “dark tourism” was introduced by Foley and Lennon (1996) to express the obsession of visitors and tourists with death. The term was profoundly adopted in the tourism literature to describe travel-associated sites with a dark history, particularly related to death, war, disaster and horrific incidents (Stone & Sharpley, 2008; Light, 2017; Iliev, 2021). Dark tourism, as the parental terminology, goes by many names, with the second most adopted being thanatourism and other terms such as morbid tourism, grief tourism and black tourism (Wang & Luo, 2018; Martini & Buda, 2020).

Today, dark tourism is considered a unique brand where a diverse range of death-related tourism products can manifest into a tourist experience (Stone, 2013). The main attraction of dark tourism is the visitors’ perceived relationship between life and death (Wang et al., 2021a). Besides cultivating historical consciousness, visitors explore national identity and learn from the past to strengthen disaster preparedness (Gotham, 2017). There is a prevalent opportunity for developing dark tourism sites to elevate the economic status of local communities. The growing niche market of dark tourism is with huge potential. Several issues are lingering in the dark tourism market and products. Among them is the role of commercial versus non-commercial dark attractions (Powell & Iankova, 2016). Dark tourism provides a valuable and beneficial walk through history by experiencing social memory of past events to present-day society (Wight, 2020). History would provide wisdom and prepare the community towards future foresight. The development of nation-building would be much strengthened when society values the lesson of the dark events of the past.

This study proliferates the literature gap in dark tourism based on reputable publications as a comprehensive view rather than previous reviews that bridge the gap based on specific constructs such as tourism experience (Iliev, 2021; Rajasekaram et al., 2022) and differentiating dark tourism and thanatourism with heritage tourism (Light, 2017). Past studies have shown that dark tourism is an important segment of the tourism sector and serves as knowledge-based and historical artefacts that future generations can learn and benefit from. The macroscopic view of dark tourism and the lack of understanding of the knowledge structure derived from past influential studies must be added. Drawing from the knowledge structure enables future studies to propose the theoretical and conceptualization of dark tourism. This study covers the whole concept of dark tourism and explores its knowledge structure through bibliographic visualization. The significance of this study would contribute to research and practice, particularly in building the economy and prosperity of the local community that has endured suffering and tragic history. A field’s intellectual structure can be mapped through bibliometric analysis by visualizing the interrelated themes and uncovering the fundamental research streams. Bibliometric approach, with its many analyses, has been applied in many studies, such as human resource management (Andersen, 2021), entrepreneurship (Hota et al., 2020; Tan Luc et al., 2022) and knowledge management (Bernatović et al., 2022; Fauzi, 2023a). The rapid growth of dark tourism studies necessitates a detailed bibliometric review to uncover this field’s knowledge structure and science mapping.

Bibliometric analysis has recently gained popularity in exploring and analyzing huge amounts of scientific data (Donthu et al., 2021). It has been adopted in many scopes primarily to quantitatively evaluate past research activities, track transformative processes, investigate the knowledge landscape and predict trends and anticipated themes in various fields (Kastrin & Hristovski, 2021). Today, the contemporary bibliometric analysis incorporates two distinct but methodological approaches (Noyons et al., 1999) 1) performance analysis: the procedure includes counting the performance output based on domain (e.g., publications, citations by authors, institutions and countries). 2) science mapping: a spatial and temporal representation approach to examine a field’s scientific structure and dynamics (Van Eck & Waltman, 2014; Chen & Song, 2017). Based on the paper’s objective, the two bibliometric analyses based on science mapping are employed:

Bibliographic coupling: Bibliographic coupling classifies links between publications as two publications referencing the third publication within their bibliographies (Martyn, 1964). It is a form of statistical calculation that detect a particular subject matter addressed by the two articles (Boyack & Klavans, 2010). This connection is known as the coupling strength, where the higher the citation of the third item of the two publications share, the higher their coupling strength or link strength (Jaafar et al., 2023).

Co-word analysis: Co-word analysis examines publications’ actual content in contrast with other analyses based on citation analysis (either cited or citing publications). It is derived from author keywords, titles, abstract and full text (Donthu et al., 2021). Co-word assumes that words frequently appear to form distinguish themes among one another. The output of the co-word analysis is themes formed by the network of words, representing a conceptual field space (Zupic & Carter, 2015).

Research design and data collection procedure

We employed the following search string: “dark tourism” OR “thanatourism” OR “morbid tourism” OR “grief tourism”. This search string was applied in the “TS” search option (title, abstract and author keywords) in the Web of Science (WoS) database. WoS has been the most robust bibliographic database for more than 40 years, until 2004, when Scopus emerged (Pranckutė, 2021). It is considered the best database with robust and impactful publications, as it has been indexing scientific articles for the past 40 years (Adriaanse & Rensleigh, 2013). Similar bibliometric studies have applied WoS as the preferred bibliographic database (Leung et al., 2017; Hota et al., 2020; Fauzi, 2023b). This analysis limits only journal publications by excluding other publications such as books, book chapters, conference proceedings, editorials and white papers. Limiting journal publications would ensure that the knowledge structure is from peer-reviewed and reputable publications in the literature (Khaldi & Prado-Gascó, 2021; Budler et al., 2021). The software VOSviewer 1.6.18 was used to perform the network visualization (van Eck & Waltman, 2014). The validity and reliability of the research rely on the fundamental basis of bibliometric methodology as a quantitative approach to analyzing the bibliographic database. All relevant publications based on the search strings were retrieved from WoS, the leading scientific database in the world. This approach enables accuracy, validity and reliability by demonstrating evidence of impact productivity (Furner, 2014).

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

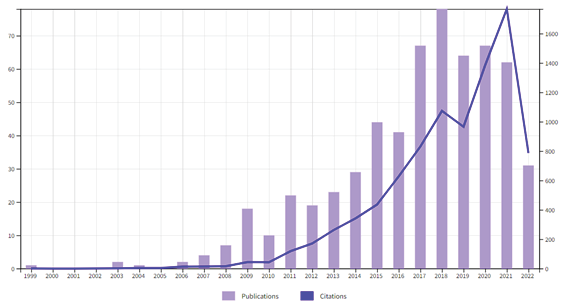

The search was performed on August 13, 2022. 737 documents were retrieved after the first search. After filtering only journal publications, the search returned to 592 journal publications. The total citations were 3,459 and 2,936 (without self-citations). The H-index recorded for these publications was 45, and the average citation per item was 15.05. Figure 1 presents the number of publications produced and citations received from 1999 to 2022 (August). The number of publications increased steadily since the mid-2000s and peaked in 2018. Even though the number of publications is rather consistent at around 60 publications a year, the significance of dark tourism studies within the tourism industry is crucial in today’s highly competitive tourism market.

Figure 1: Number of publications and citations on dark tourism

Based on leading countries producing dark tourism publications (Table 1), England leads with 122 publications, 2159 total link strength (TLS) and 3,039 citations. The United States and Australia come second with 88 and 78 publications, respectively. The table is ranked based on the number of publications. It can be seen that some countries, despite producing fewer publications, some countries received more citations, for instance, Canada, Netherlands and Israel. These three countries have produced significant dark tourism studies from war and battle events. Canada has low TLS due to its isolated and localized publication network referring to studies within the country only, unlike the European countries that are closely associated. Netherlands produced substantial TLS contributed by the Eighty Years’ War, or the Dutch Revolt, while Israel is linked to the Holocaust (Abraham et al., 2022).

Table 1: Top 10 countries publishing on dark tourism

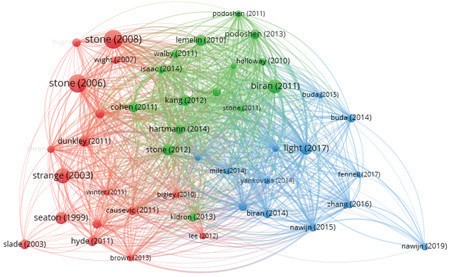

Out of the 592 documents in the bibliographic coupling analysis, 47 met the 41-citation threshold. The analysis produces three significant clusters. Based on total link strength (TLS), the top 3 documents in bibliographic coupling are Light (2017) (659 TLS), Isaac and Çakmak (2014) (473 TLS) and Yan et al. (2016) (414 TLS). Table 2 presents the top 10 documents in the bibliographic coupling analysis.

Table 2: Top 10 documents in bibliographic coupling analysis

Subsequently, the bibliographic coupling network map produces three significant clusters (Figure 2). The clusters are rather distant and separated, suggesting the themes are unique. These keywords formed and elaborated on each thematic cluster to forecast trends in a particular field (Donthu et al., 2021). The following discusses the current trends and future development of dark tourism. The clusters are labeled according to the author’s inductive and qualitative interpretation.

Figure 2: Bibliographic coupling analysis on dark tourism

Cluster 1 (red): Cluster 1, with 17 documents, is labeled as the “ niche area of dark tourism”. Chronis (2012) put forth the issue of tourism imaginaries that are emotion-conferring, value-laden associated with a particular place. These imaginaries are based on four narrative domains: emplaced enactment, moral values and emotional connection. Causevic and Lynch (2011) explore the Phoenix tourism concept, a distinct period in post-conflict tourism. Phoenix tourism is categorized as a sub-category of dark tourism. It functions as a process in tourism sites, developing from conflict into a new heritage. Lee et al. (2012) explore peace tourism as the opposite spectrum of dark tourism. The notion of peace tourism is based on the backdrop of the sunshine policy to improve the inter-Korean relations between the North and the South within Mt Kumgang tourism resort. It allows South Korean companies to invest in the North and expand their business, thus creating peace and harmony.

Cluster 2 (green): Cluster 2 with 15 documents is labeled as “ motivation and drivers of dark tourism visitation”. Isaac and Cakmak (2014) examined visitors’ motivations for an iconic dark site in the Netherlands, the transit camp of Westerbork. It was found that visitors are driven by ‘self-understanding’, ‘curiosity’, ‘must-see’, ‘conscience’ and ‘exclusiveness’. In another study, Kang et al. (2012) assessed tourist motivations for visiting Jeju April 3rd Peace Park, Korea. The key motivation is ‘obligation’ as the tourist’s main drive, includes personal duty and a sense of obligation. On-site experience and benefits gained from history were also the reason for visiting the place. From the perspective of musical performance art, black metal is rooted in its history of past violence, steeped in anti-Christian themes (Podoshen, 2013). Tourists were found to seek landscape images and topographical reality. Dark tourism usually embraces reviving the geography of memory at places with a shadowed past (Hartmann, 2014).

Cluster 3 (blue): Cluster 3 with 13 documents is labeled as “ progress in dark tourism”. This cluster’s recent publication deals with progress and advanced theme in dark tourism. Zhang et al. (2016) probed into tourists’ intrapersonal constraints and past experiences towards revisiting intentions to the victims’ memorial of the Nanjing Massacre. Four sub-dimensions are identified. Namely, culture, escape, emotion and incuriousness. Yan et al. (2016) study were the first to employ structural equation modeling in dark tourism research. The study investigated tourists’ motivation and experience towards their emotional reactions. It was discovered that curious tourists are likely to engage cognitively through learning about the dark space surrounding the sites. Buda et al. (2014) investigated the emotions and affection of tourists when visiting dark and ongoing conflict sites. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the West Bank present an area of socio-political conflict that embodied emotional tourism research for future avenues.

The following table 3 presents the summary of the bibliographic coupling analysis with cluster number and colour, labels, number of publications, and representative publications.

Table 3: Summary of bibliographic coupling analysis on dark tourism

Applying the same database, the co-word analysis resulted in 57 out of 1,987 keywords based on a threshold value of 10, resulting in four clusters. The highest co-occurred keywords are dark tourism (453), death (149) and thanatourism (132). The highest frequency keywords depicted that dark tourism is the central term scholars use with other significant terminologies such as thanatourism and heritage tourism. Table 4 shows the top 15 keywords in dark tourism in this study.

Table 4: Top 15 keywords in the co-word analysis

The network structure of the co-word analysis shows compact and closely connected clusters. The four clusters intersect, particularly cluster 3 (blue) and cluster 4 (yellow), which are cross-intersect, indicating a closely related theme—these four clusters commend potential future trends within dark tourism research.

Figure 3: Co-word analysis of dark tourism

Cluster 1 (red): With 18 keywords, cluster 1 is labeled as “ dark tourism based on dark memory”. This cluster comprehends the basis of dark tourism. The unique value of dark tourism is its ability to engage tourists with the representation of death (Martini & Buda, 2020). Most dark tourism sites are oriented toward memory and heritage, creating strong emotional and affective reactions (Godis & Nilsson, 2018). Experience that a person possesses may or may not be shared with others will always remain in one memory (Tercia et al., 2022). Revisiting a site associated with a particular tragedy and trauma will evoke positive or negative emotions within one personal memory (Marschall, 2012). Dark tourism site presents a place of past horrors and deaths where ‘unwanted’ memories prevail (Isaac & Budryte-Ausiejiene, 2015). The memory is embodied in the site, where aroused collective memories of traumatic history produce intense emotional reactions (Zheng et al., 2020).

Cluster 2 (green): Cluster 2 discusses “ improving user experience in dark tourism “. Although such tourism is based on dark meanings, the user experience does not always have to be dark (Jamalian et al., 2020). User experience is associated with tourism images that correlate with destination quality and user experience satisfaction (Kim & So, 2022). Gaining a better understanding of lived visitors’ experience contribute to the significance of dark tourism in traumatic sites related to natural disaster, catastrophic incidents and war (Zhang, 2021). Dark tourism operators have adopted several technologies to enhance the user experience, such as applying virtual reality to construct a reality of representation in the form of death, suffering, tragedy and pain (Fisher & Schoemann, 2018). Qian et al. (2022) identified four dark tourism destination images in their study of the earthquake-ravaged China in the city of Beichuan. The image of the educational and memorial destinations was the most significant on-site tourist experience and intention to visit. Meanwhile, travelers seemed to have less of an impression of a leisure destination and a horrific landscape..

Cluster 3 (blue): With 12 keywords, cluster 3 is labeled “ motivation and attraction towards death and mortality”. The drive to visit dark tourism sites is similar to tourists visiting heritage sites (Iliev, 2021). Wang et al. (2021b) explored the emotional awe experience in dark tourism. The study found that dark tourism sites arouse awe in tourists, highly influenced by the feeling of authenticity experienced by tourists. It was recommended that creative methods to enhance authenticity perception could inspire awe, such as applying virtual reality on sites and locality. The push-pull theory is the most widely discussed in understanding tourist behavior (Pearce, 2014). Push factors explain a person’s desire to travel, while pull factors explain destination features and attraction factors (Bhati et al., 2021). Within the dark tourism background, the main push factors are identified as thrill-seeking (Podoshen, 2013), remembrance (Yoshida et al., 2016), death and dying (Martini & Buda, 2020) and education (Kang et al., 2018). Meanwhile, pull factors include history, location and artefacts, identity and cultural heritage in the tourism sites (Bozic et al., 2017; Azevedo, 2018).

Cluster 4 (yellow): With 10 keywords, cluster 4 is labeled as “ motivations on war and battlefield dark tourism “. This cluster is centralized in war and battlefield tourism. War tourism has increased in parallel with the upsurge in growth in tourism (Mirisaee & Ahmad, 2018). War sites and remnants stimulate individuals motivated by novelty experience, distinct from other conventional tourism. Based on the Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, Alabau-Montoya and Ruiz Molina (2020) utilized digital technology to elicit emotion and provide insight to visitors. Digital technologies, such as augmented and virtual reality, are a practical instrument for enhancing the visitor’s experience in war heritage tourism and boosting the spread of word-of- mouth communications towards prospective tourists. The potential of digital technology is seen as one of the initiatives to elevate tourist post-visit impact, influencing their cognitive and emotional domain by meeting their satisfaction level. Tourist satisfaction is the strongest predictor of tourist intention to visit war tourism sites (Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2021). Other factors include experience quality, destination image and perceived value.

The co-word analysis summary is presented in Table 5, comprising cluster number and colour, cluster labels, number of keywords, and representative keywords.

Representative Keywords

(red) Dark tourism based on dark memory

(green) Improving user experience in dark tourism

(blue) Motivation and attraction to- wards death and mortality

(yellow) Motivations on war and battle-

field dark tourism

16 Dark tourism, heritage, memory, slavery, history, pun- ishment, prison

15 Tourism, destination image, perceptions, management, authenticity, satisfaction, impact

15 Death, experience, motivation, perspectives, attraction

11 Thanatourism, war, museum, war, battlefield tourism,

pilgrimage

Fundamentally, the implication of theory in dark tourism is its relation to the niche and sub-domain of dark tourism. War tourism is the most distinct within the specific scope of dark tourism. It is dark niche tourism that specifies war and battlefield sites (Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2021). Battlefield is worthy of study to visitors as it reflects the people’s strength and ability to

emerge from the shadow of war and their displeasure at confronting the brutal truth of past wars (Lee, 2016). Light (2017) argues that dark tourism is similar to heritage tourism in that both terms are related to visiting sites with a strong association with death and suffering. To better define the two concepts of dark and heritage, Ivanova and Light (2018) proposed the definition of ‘lighter dark tourism’ corresponding to heritage tourism. It is also linked to death and suffering but is intended to focus on entertainment and is oriented toward commercialization. In a wider sub-domain of heritage tourism, memory tourism relates to personal heritage experiences that link the past and present of personal or social relations (Godis & Nilsson, 2018). It primarily relates to personal loss and geographical connection to past events (Marschall, 2012). In cluster 1 of bibliographic coupling, phoenix tourism (Causevic & Lynch, 2011) and peace tourism (Lee et al., 2012) are a segment of dark tourism that shed light on the brighter spectrum of dark tourism.

This study also implied a need to recognize the determinants and predictors of tourist visitation to dark tourism sites and places. From the two analysis, the fundamental themes derived was “motivation and drivers of dark tourism visitation” in cluster 2 of the bibliographic coupling and “motivation and attraction towards dark tourism” in cluster 3 of the co-word analysis. However, most past studies have been poorly conceptualized concerning the tourist’s experience (Lacanienta et al., 2020). Tourists experiencing dark tourism should not develop negative emotions such as vengeance, retaliation, revenge or fear that might disrupt community peace and harmony. Instead, tourists experiencing dark tourism sites should develop positive affection. The nature of tourist emotion derivation would be the unique feature that defines dark tourism distinctively compared with other tourism (Nawijn et al., 2016).

Individuals visiting dark tourism sites were triggered into the learning process to convert the emotional experience into mean- making (Sigala & Steriopoulos, 2021). Based on Thompson (2004, p. 12) on the “25 best World War Two Sites”, it was profoundly noted that “a battlefield is not necessarily a good place due to thousands of loss of life, but it is indeed an important one” (p. 12). The importance of war sites was depicted in the battle of Gallipoli, where Australia and New Zealand suffered immense casualties, creating a de facto origin for both countries (Stone, 2012). Dark tourism should be depicted as sites of reflection, learning from mistakes and developing fundamental knowledge for community development. By understanding the historical flow of dark sites, the next generation will be able to learn from the past, embrace and take advantage of developing the community and nation upbringing.

User experience, image and satisfaction are the main themes derived from the two bibliometric analyses. User experience at dark tourism sites is unique and complex, where calls have been made to provide visitors perceive and internalize experiential outcomes (Farrelly, 2019; Zhang, 2021). To satisfy the tourist experience, tourism players must fulfill their value requirements and deliver a unique value offering (Hadjielias et al., 2022). Some dimensions of experience, in the form of introspective and relational experience, help illuminate dark tourism values (Zhang, 2021). The experience would lead to satisfaction among visitors that resonate well with their behavioral intention and loyalty, leading to revisit intention (Wang et al., 2021b). Revisit intention is considered a long-standing phenomenon in behavioral tourism. Within tourist decisions and choices, revisit intention relates to their expectation and motivation for the tourism experience and their perception of a destination’s image (Tosun et al., 2015). Destination image was highly related to tourist visit intention and on-site experience (Qian et al., 2022). Destinations and sites should focus on developing and creating tourist sites’ positive image, authenticity and attachment as crucial engagement factors for tourists. The sites should be perceived as authentic and original without any fictitious or fake reconstruction. The higher perception that a dark site is authentic, the greater the tourist intention to visit or revisit a particular destination (Kim & Barber, 2022).

To further increase tourist satisfaction, an interactive approach through interactive technologies would provide a leading technology-empowered tourist destination (Ponsignon & Derbaix, 2020). Tourists visiting dark sites are satisfied with the interactive quality experience. It is supplemented with cognitive, emotional, behavioral and relational outcomes to create interactive consumption meaning and loyalty (Willard et al., 2022). This reciprocal interaction between the service provider and visitor contributes to the experiential outcome. Digital technologies are popular approaches to creating accessible visits, enhancing edutainment and increasing visitor experience. These digital technologies range from simple media tools to sophisticated technology like virtual reality (Bourgeon-Renault et al., 2019). Krisjanous (2016) suggest that dark tourism sites should enhance their website, creating digital engagement towards visitors’ pre-visit. Drawing from 25 dark tourism websites, it was found that they increase visitors’ motivation by shaping their expectations and signaling behavior (Heuermann & Chhabra, 2014). Such behavior is crucial for dark tourism as it offers unusual characteristics compared to other types of tourism. However, digitalization and social media create unfiltered accessibility to the consumption of death and disaster events (Martini & Buda, 2020). Communication through these channels should incorporate affective and cognitive value in delivering news on the disaster. The least they can do is donate and rapidly spread information through various channels. Multiple forms of social media, news broadcasts, the internet and other media outlets will burst with horror and pain for those suffering from a disaster. Without affection, the audience and the general mass do not connect with death or disaster sites, impacting the less fortunate.

Despite the “dark” notion of dark tourism, advertising dark tourism products should be commensurate with positive emotions rather than bad. Practitioners, scholars and stakeholders must communicate and take positive outcomes of disasters and tragedies leading to dark tourism. The best example was the 2004 tsunami that hit Banda Acheh, Indonesia. A peace agreement was attained between the Indonesian government and the Free Acheh Movement, depicted through unity and shared grief among the communities (Tercia et al., 2022). Dark tourism sites should be identified by the image of memorial places and education rather than the “image of fear”. The fear factor in dark tourism may attract pre-interest to visit, but in the long run will diminish their revisit intention (Light, 2017).

The literature lacks the perspective of the local community in their role toward dark tourism sites. This phenomenon is contributed by a few studies viewing from the local community’s perspective due to the traumas and agony on the historical landscape of the dark sites. As such, future studies should look into how dark tourism sites can promote peace and harmony. The role of dark tourism can invigorate the sentiment of nation-building, where the community learn and develop racial harmony and embrace societal differences. Furthermore, future studies should focus on local people as the sustainability of tourism development largely depends on the destination community’s goodwill (Wright & Sharpley, 2018). Preference must be given to the local community’s attitude as it can mitigate the negative impact and support the local industry growth (Sarkar et al., 2022). The aspect of socio-economic development stemming from dark tourism should also be emphasized in future studies. In other tourism, such as eco-tourism and sports tourism, the sustenance of economic activities generated are pouring into the local communities. The antecedents and impact should be studied to identify the contributing factors towards dark tourism sites and community development.

LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE WORKS

This review possesses some limitations. The restriction of the WoS database could have limited the inclusion of relevant sources and publications, despite its known scientific bibliographic quality (Maia et al., 2019). The inclusion criteria of limiting publications in English from this database also limit the rich literature of dark events that have occurred throughout history. Other academic work in different languages might have provided different perspectives and meanings of dark tourism based on a specified dark context described in the country and regional-specific language. Therefore, future studies should explore different databases to capture significant dark events in specified contexts. Future studies are encouraged to engage in a similar bibliometric approach to improve the design of the dark tourism study context to sharpen its intellectual and knowledge structure.

CONCLUSION

This review provides a fundamental understanding of the dark tourism literature by visualizing the knowledge structure of the subject science map. This study depicted significant differences from past reviews. The study by Light (2017) is more fundamental towards conceptualizing dark tourism based on the definition, scope and rationalizing of the politics and ideology of dark tourism. This study holistically presents the underlying knowledge of dark tourism, in contrast to the evaluation of the dark tourist experience presented by Illiev (2021). From a bibliometric standpoint, Bhowmik (2021) delineates the concept of heritage tourism, comprising an important element of dark tourism. Despite that, Bhowmik’s study did not present an overview of dark tourism’s past, present and future themes, which are presented by this study. Compared with another review by Rajasekaram et al. (2022), this study has shown that dark tourism is associated with different niches and subcategories of dark tourism, such as peace and Phoenix tourism. Rajasekaram’s study only looks into how past studies in dark tourism are reflected on the spectrum of darkest to lightest end. This study also emphasizes research streams related to consumers in the form of dark memory, user experience and motivations toward engaging in dark tourism. Similar clusters were identified within the two bibliometric analyses of bibliographic coupling and co-word analysis, such as tourist experience in visiting dark tourism sites and motivation, drivers towards dark tourism sites, war and battlefield tourism. These similar themes indicate that the field is still in its infancy, calling for further studies to delve into the fundamental knowledge of the subject. Nevertheless, the role of dark tourism is imperative, especially in the local community affected by dark events, and is crucial in nation-building and the proliferation of social wellbeing. The novelty of this study is the impact of dark tourism on the tourism eco-system and the use of digital technology in elevating the value of service to tourists visiting dark tourism destinations. This study challenges scholars’ understanding of current and future research streams based on determinants of tourist motivations and drivers of dark tourism destinations. The drivers could be at the end spectrum of human needs of grieving and suffering concerning death and mortality, and war dan battle events compared to other tourism sectors that rely on joy and entertainment.