Razmotrit ću Krležinu recepciju Brest-litovskog mira (2. prosinca 1917. – 2./3. ožujka

1918.), ugovora o miru sklopljena 3. ožujka 1918. između Sovjetske Rusije i Centralnih

sila (Njemačke, Austro-Ugarske, Turske – Osmanskog Carstva, i Bugarske) (usp.Mombauer 2014:57;Crutwell 1982:479), u kontekstu njegovih

dnevničko-memoarskih zapisa Davnih dana, 1

kao našega jedinog literarnog dnevnika iz Prvoga svjetskog rata (dakle, ne mislim ovdje,

tragom zapažanja Marijana Matkovića, na ostale naše dnevnike iz Prvoga svjetskog rata s

literarnim odrednicama, nego na literarni dnevnik) (Matković 1985:188). 2

Milan Vlajčić (1963:588) vjeruje kako bi svaki

“razgovor o Miroslavu Krleži morao (…) da započne Davnim danima” ili

tautološki – kako su sva Krležina djela najavljena u njegovim

prvosvjetskoratnim dnevnicima, a navedeno posebice primjenjuje na

roman-rijeku, njegov posljednji roman Zastave (Ibid. 588–589). 3

Tako npr. Aleksandar Šljivarić ističe da “embrionalni začetak, datum rođenja

Hrvatske rapsodije (Savremenik 1917:5) treba tražiti

na relaciji putovanja Zagreb – Nova Kapela – Batrina – Požega početkom travnja godine

1917.” (Šljivarić 1957:1011), što ga je

zabilježio u Davnim danima navedene godine.

U interpretativnoj niši književne i političke antropologije, s obzirom na to da je

mnogima zahvaljujući stilističkim i naratološkim interpretacijama postala zazorna

(auto)biografska kontekstualizacija, i centripetalna i centrifugalna, tako da do Lasićeve

Kronologije (1982.) nismo imali Krležinu biografiju, kontekstualiziram

prvu ratnu (1914.) godinu Krležinim biografskom kronosom – Krleža ima (svega) 21 godinu, a

prvi dnevnički zapis pod datumom 26. veljače 1914. svoga literarnog dnevnika Davni

dani određuje fragmentom dramske Salome

4

koja uz dramsku Legendu (tiskana u Marjanovićevim Književnim

novostima iste godine) čini Krležine prve dramske tekstove.

TRI RATA KAO KRLEŽIN RITUAL PRIJELAZA

Zamjetno je iz psihobiografske niše da pored te povijesno-globalne apokaliptične

situacije Krleža započinje pisati Davne dane i nakon vlastitih, osobnih

golgotskih scena. Naime, godina 1913. presudna je za definiranje njegova životnog

hodograma kada dozrijeva zamisao o bijegu iz ugarske vojne akademije Ludoviceum. Vojnički

dril u ugarskim vojnim učilištima Krleža prolazi kroz pet godina, od 1908. do 1913., od

petnaeste do dvadesete godine – prvo kao pitomac Ugarske kraljevske kadetske škole u

Pečuhu (1908.–1911.) a zatim kao akademac u Ludoviceumu (1911.–1913.) (Usp.Zelmanović 1987).5

Pored ideje bijega iz Ludoviceuma, kada shvaća u tim formativnim godinama da vojni poziv

nije njegova vokacija, te, 1913., godine Krleža razvija i ambivalentan politički stav, u

skladu vlastite antitetičke vrteške:6

riječ je o mješavini starčevićanske ljubavi prema Hrvatskoj i – paradoksalno – o

sentimentalnoj viziji južnoslavenskog ujedinjenja (Lasić 1982:102). I travnja 1913. godine Krleža u skladu s vizijom o

južnoslavenskom ujedinjenju napušta Ludoviceum; stiže do Pariza odakle preko Marseillea i

Soluna dolazi u Skoplje da se pred srpski rat s Bugarima na Bregalnici prijavi kao

dobrovoljac u srpsku vojsku (ibid.:104).

Točnije, u vrijeme Balkanskih ratova (Prvi i Drugi balkanski rat, 1912.–1913.) Krleža se

dva puta prijavljuje u srpsku vojsku; pritom je 1912. odbijen, a 1913. godine osumnjičen

je kao austrougarski špijun i vraćenaustrijskim vlastima u Zemunu. 7

Drugi bijeg gotovo da sadrži i sekvence pustolovnog romana, što se tiče pokušaja

(interpretativni modus iz autobiografske niše) spajanja sa Srbima na Bregalnici, gotovo

nalik na Melanijino putešestvije s kavaljerom Novakom, da

kontekstualiziramo navedenu anabazu i fiktivnim svjetovima Krležina prvog romana

Tri kavaljera frajle Melanije. Staromodna pripovijest iz vremena kad je umirala

hrvatska moderna (1920.–1922.). Iskustvom na Bregalnici nastaje Krležino

razočaranje ondašnjim političkim konceptom južnoslavenskog ujedinjenja koje je trebala

sprovesti Srbija-Pijemont: shvaća kako je bitka na Bregalnici “možda nerazmjerno

tragičniji događaj od ovoga rata, kod Bregalnice ostvarilo se po drugi put ono što je

proricao Dostojevski, da će se ovi balkanski seljaci poklati i pobiti do istrage ako dođu

do topova!” (DD, 248). Time je Bregalnica

poništila sve Krležine ideje, iluzije o ilirizmu, te je nasuprot

austrijskom Alžiru sada spoznao južnoslavenski, srpski Alžir ekspanzionističke državne

sile (Lasić 1989:104). Ukratko, lipnja 1913.,

nakon dva mjeseca putovanja, dolazi na Bregalnicu gdje nastaje buđenje od južnoslavenskog

koncepta ujedinjenja pod jugorojalističkom vizurom dinastije Karađorđević,

monumentaliziranog u maketi Meštrovićeva Vidovdanskog hrama. 8

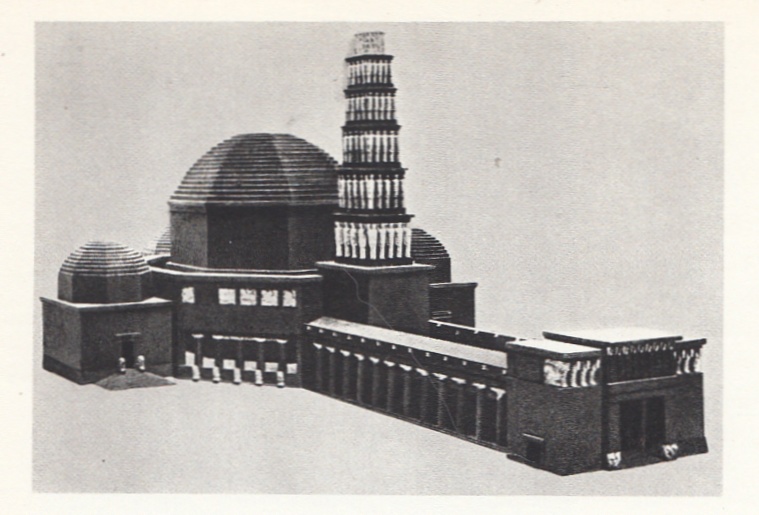

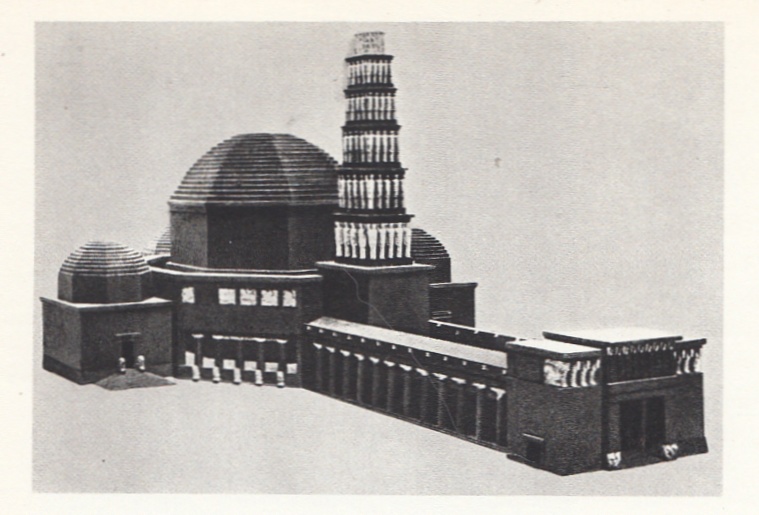

Naime, u tom razdoblju Meštrovićeva drvena Maketa Vidovdanskog hrama

(1907.–1912.) objavila se kao prva umjetnička vizualizirana predodžba kosovskog mita s

političkim podtekstom rojalističkog Jugomitosa.9

Tako se te 1913. godine Krleža kao dezerter vraća u Zagreb te nastaje definitivan rascjep

između oca, činovnika u Austro-Ugarskoj (Miroslav Krleža stariji) i sina

(Miroslav Krleža mlađi): za oca, Krleža je bio “dezerter, nitko i ništa,

njegova živa sramota” (Lasić 1982:109). Iz

svih ovih pozicija – globalnih i osobnih Golgota – Krleža počinje voditi

dnevničko-memoarske zapise Davnih dana kao“dramu s tisuću lica” (Matković 1985:187) – u 21. godini, u

apokaliptičnoj godini početka Prvoga svjetskog rata.

Pored 1913., i 1914. godina višestruko se očituje kao Krležino

prijelomno razdoblje: početak rata i slom Internacionale koja je

nestala “kao duh sa spiritističke seanse” (DD2,

283). Zadržimo se na slomu Druge internacionale; početak

prvosvjetskoratno-paklenog simultanizma Krleži je označio i apsolutni gubitak vjere u

Drugu internacionalu – “monumentalnu mramornu boginju kojoj je po Marxu bilo namijenjeno

da spasi Evropu od brodoloma” (DD, 417) – a

koja je umjesto promocije internacionalizma, prihvatila politiku/strategije obrane

singularnih, nacionalnih interesa, te Stanko Lasić navedene segmente iščitava kao

prijelomni trenutak oblikovanja Krležinih svjetonazora u okviru kojih prihvaća lenjinsku

varijantu (Lasić 1982:115, 118)

interastralnih kanonada (DD, 356;

201).

Zadržimo se nadalje na kronologiji Krležina života te apokaliptične godine začetka Prvoga

svjetskog rata. U kolovozu 1914. godine dobiva poziv austrougarskih vojnih vlasti da se

javi radi regrutacije; odbijen je jer ima samo 46 kg (Krležijana 2:562), što je Ranko Marinković

literarizirao u Kiklopu (1965.) u sceni Tresićeve regrutacije. Ipak,

prosinca 1915. Krleža je mobiliziran i nalazi se u pričuvnoj časničkoj školi (25.

domobranska pukovnija) – u kasarni koja je bila smještena u bivšoj školskoj zgradi u

Krajiškoj ulici u Zagrebu (Lasić 1982:123,

125). Nadalje, što se tiče ratnog životopisa, a ovdje fragmentarno iznesenog

prema Lasićevoj Kronologiji (Lasić

1982), srpanj i kolovoz 1916. provodi na ratištu u Galiciji – kao dio mase

kanonenfutera (DD, 126;

usp. dnevnički zapis pod nadnevkom 17. siječnja 1918.) tijekom prve Brusilovljeve

ofenzive. Tih galicijskih mjeseci, koji nisu zastupljeni u Davnim danima,

Krleža ima uza se tablete cijankalija koje je dobio u Lovranu “od jednog apotekara s kojim

se sprijateljio: namjerava se otrovati ako bude teško ranjen ili u kakvoj drugoj

neprilici” (Visković 2000:152). Iz

navedenih fragmentarnih podataka o Krležinu životu do 1916. godine, sasvim je sigurno kako

su na njega najviše utjecala ta tri rata (metonimija Velikog meštra sviju

hulja): Prvi i Drugi balkanski rat (1912. i 1913.) te Prvi svjetski rat, kako

je to uostalom često i isticao.

Ukratko: Krležini se Davni dani mogu odrediti kao aktivistička

literatura činjenice o marsijanističkoj Odisejadi i Penelopijadi.

Pritom navedeni feminino-maskulini ratni binom preuzimam iz Krležina Motiva za

noveletu (iz Davnih dana) o djevojci – koja figurira kao “neka

vrsta Penelope” i koja spoznaje da su svi njezini prosci prasci – i o

njezinu Gerichtsadjunktu (usp.DD,

31–32), a posebice prema zapisu iz eseja Iza kulisa godine 191810

gdje bilježi kako naše Penelope – koje nisu ratnice, ali ratuju – ne

misle “da bi se njihov Odisej mogao jednoga dana vratiti, ovjenčan lovorikom” (DD2, 132).

Dakle, dok je 1913. godina ključna što se tiče životnih rituala prijelaza, ako uporabimo

Van Gennepovu trijadnu konstrukciju životnih rituala, Stanko Lasić dokumentira da je

godina 1914., dakle, slom Druge internacionale kao i slom Krležine vjere u Ilicu 55, u

socijaldemokraciju Vitomira Koraća, prijelomni trenutak oblikovanja Krležinih

svjetonazora.11

Iz navedene kontekstualizacije krećem u interpretaciju Krležina Razgovora o

Brest-Litovsku kao političkog manevra pro futuro, no, iz

perspektive 1917. godine.

Ivan Meštrović,drvena Maketa Vidovdanskog

hrama (1907.–1912.)

BREST-LITOVSKI SUKOB: LENJIN – TROCKI

Zapis Razgovor o Brest-Litovsku (1918) (prvi put objavljen u

Republici, 1967., br. 7–8), zabilježen kao polemički disput što ga

Krleža vodi “s jednim tipičnim trabantom Hrvatsko-srpske koalicije”, 12 a koji će se pojaviti“u jednom od kraljevskih SHS-kabineta kao ministar” (DD2, 179), inkrustiran je u dnevničko-memoarske

zapise Davnih dana, i to u njegovu drugom izdanju, kao Krležina apologija

mira što ga je Lenjinova Rusija potpisala s Centralnim silama u funkciji

očuvanja Oktobarske revolucije. Krleža tih davnih dana

koji će rezultirati s približno 20 milijuna mrtvih vojnika i civila (“Prvi svjetski rat”, URL),13 istinski vjeruje u Lenjinove interastralne kanonade asimptote

Slavjanstva (DD, 356; 201).14

Kao etičku dostojnu gestu nasljedovanja apostrofira rusku

politosferu koja je prva odbacila noževe (DD, 280–281), i iz perspektive 1918. Brest-litovski

mir (3. ožujka 1918) određuje kao anticipaciju “internacionalističke

solidarnosti proletarijata evropskog”, s obzirom na to da su masovni štrajkovi

počeli u Francuskoj i u Berlinu (DD2,

188), kao politički manevar pro futuro (DD2, 180). Međutim, u podrupku

teksta, pisanom iz perspektive 1967. godine, kao korekciju vlastite interastralne

retorike upućuje kako su se već u veljači 1918. “sve moskovske iluzije o

generalnim štrajkovima na terenu centralnih vlasti, a naročito u Berlinu”

rasplinule pod “terorom soldateske”, a “lenjinska koncepcija mira u Brest-Litovsku

našla se u bezizlaznoj ulici” (DD2,

188). Dakle, riječ je o dvostrukoj optici o Brest-litovskom miru, iz

perspektive 1918. i 1967., posljednje – u povodu obilježavanja pedesete obljetnice

Oktobra, odnosno godine kada je Krleža potpisao Deklaraciju o položaju i

nazivu hrvatskog književnog jezika (objavljena u tjedniku

Telegram 17. ožujka 1967.), nakon

čega podnosi ostavku na članstvo CK SKH i pritom se povlači iz javnog života

(Lasić 1982:403).

15Navedenu dvostruku optiku (1918. – 1967.) moguće je jednako tako

dokumentirati i što se tiče Krležine ekspresionističke drame Kristofor

Kolumbo (1918. prvi put tiskana u knjizi Hrvatska

rapsodija, Naklada Đorđa Ćelapa, Zagreb, 1918., zajedno s istoimenim

tekstom i Kraljevom) koju je prvotno posvetio Lenjinu da bi

naknadno izbrisao posvetu.16Naime, navedenu jednočinku, u kojoj postavlja sljedeće paralelizme,

duhovnopovijesne analogije, gotovo u smislu morfologije svjetske povijesti

Oswalda Spenglera: Kolumbo – Lenjin, Santa Maria – Aurora, piše u vrijeme

Oktobra 1917. godine i godinu dana kasnije u trenutku objavljivanja posvetu

briše. U Napomeni o Kristovalu Kolonu(Književna

republika, 1924., br. 5–6) ističe kako je tada, u vrijeme pisanja

jednočinke, legende, Lenjina doživio na tragu Maxa Stirnera

(anarhoindividualizam) i Mihaila Bakunjina (kolektivni anarhizam), s tim dvjema

anarhoidnim idejama koje je tematizirao, primjerice, i u drami Golgota

(1922.) u kojoj će dokumentirati rasap politike

prijateljstva među radničkom pokretom. Tako Gomila,

koja nastoji ubiti kolumbovskog Admirala, performativno upućuje: “Mi nismo

anarhisti kao vi. Nas može spasiti samo organizacija rada! Taylorov system!”,

što čini autorsku ironizaciju njihova jednodimenzionalnoga, cikličkog pogleda na

svijet. Možda posvetu briše i iz konteksta Brest-litovskog mira u okviru

kojeg je nastao sukob Lenjina i Trockoga. U tome smislu prvotno shvaćanje

Lenjina iz 1917. godine, kada ga je u upisao u štirnerijansko, solipsističko,

šopenhauerovsko shvaćanje, blisko je Krležinoj imaginaciji

Salome iz prvoga dnevničkog zapisa Davnih

dana; Kolumbova krilata lađa i njegova plovidba u tangenti, u

nepovrat ka zvijezdama bez kompasa i bez globusa, bliska je Salominoj astralnoj

strategiji – “Ten je kod žene najmanje važna stvar! Važne su zvijezde” (DD, 11), odnosno Kolumbovim

performativima: “Novo ne može biti u krugu. Novo ne može biti u vraćanju”, s

obzirom na trajno faustovsko traganje smisla ljudskog postojanja. |

DVIJE IDEJE SLAVENSTVA – JUGOROJALISTIČKA I LENJINSKI NASTROJENA KOMPONENTA

Uvod Razgovora o Brest-Litovsku čini Krležina opservacija stanja duha

Koalicije u razdoblju od 1914. do 1918, dokumentirajući kako je Brest-litovski mir

prouzročio političku dramatizaciju (i) osobnih prijateljstava, dramatsko

razdvajanje “koje će se već nekoliko mjeseci kasnije objaviti u nepomirljivoj

borbi i potrajati jednako strastveno decenijama” (DD2, 179)17

, a kao ilustraciju raskola,bipolarizacije hrvatske socijalne

demokracije na frakciju koja apostrofira “Rusko Slavjanstvo” ideologema Kerenskoga,

premijera privremene vlade Rusije 1917. godine, te na “lenjinski nastrojenu” frakciju

bilježi dijalog-duel s jednim, prozvanim koalicijskim

trabantom. Ukratko, navedeni zapis dokumentira Krležin osoban spor s Vitomirom Koraćem,

njegovom politikom jugoslavenske socijaldemokracije koja je često napuštala zahtjeve

proletarijata prihvaćajući, u ime vlastitih interesa, suradnju s vlašću (Visković 2001:145).

U tom predgovoru Krleža ironično priznaje Hrvatsko-srpskoj koaliciji “uspjeh” u

sprečavanju uvođenja vojničkog komesarijata u Hrvatsku (u razdoblju od 1914. do 1918.),

zahvaljujući njezinoj lojalnoj politici spram ugarske vlade, pod protektoratom

“madžarskoga ministra predsjednika, grofa Istvána Tisze” (DD2, 177), s obzirom na to da je glasala Tiszi za ratni budžet

(usp.DD2, 178, 190). Stvarna podloga

Krležine ironije razotkriva kako je Koalicija iz ratnog kaosa uspjela za sebe izvući

znatnu ekonomsku korist, a da bi to što bolje prikrila, štitila je “čitav niz sitnih

građanskih prava, što se manifestiralo u relativnoj slobodi štampe i sastajanja, koje se

kasnije manifestiralo u često izazovno protuaustrijsko šurovanje” (DD2, 178). 18

Krleža u podrupku Razgovora, pisanom iz

retroperspektive 1967., dokumentira predatorskom zoo-metaforom politiku

cinizma Centralnih sila, politiku makijavelizma koja je lenjinsku koncepciju

Brest-litovskog mira dovela u bezizlaznu ulicu: “Turski, rumunjski,

bugarski, njemački i austro-madžarski generali sletjeli su u Brest-Litovsk kao gavrani na

truplo ruskog imperija, da otmu iz ruskog carskog tijela Moldaviju,

Kavkaz, Kurlandiju, Litvu, Poljsku, Ukrajinu, Estoniju, Latviju i Finsku” (DD2, 188; kurziv S. M.). 19

Pri kraju razgovora optužuje rezultate/dogovore Ženevske konvencije, kontrapunktirajući

slučaj Odese gdje “strijeljaju naše zarobljenike, jer ne će da prisegnu kralju”,dok

koalicijski trabant Krležine protuargumente atribuira političkom sintagmom bečka

soba. Pritom Krleža ironično odašilje kritički (ubodni) upit:

“Da nije možda crno-žuta, da me možda nije potplatio Czernin?” (DD2, 191).

Neimenovani “tipični trabant Hrvatsko-srpske koalicije” retorikom uvjeravanja i

poučavanja nesvjesno razotkriva vlastitu politiku cinizma, makaronsku

i kompromitantnu politiku proturječnih ideologema: kao

antantofil (antantofilska Konstituanta: Lloyd George, Raymond Poincaré, Georges Clemenceau

[usp.DD2, 183]) negira

junkersku politiku; međutim, misli njihovom logikom

(princ Leopold von Bayern [usp.DD2, 182])

u pitanju ruskog boljševizma. Kao demokrat apostrofira prvaka

revolucionarne demokracije Kerenskoga koji je likvidirao cara (DD2, 182); međutim, nije shvatio da se Kerenski nikada ne bi

mogao obračunati s “Kornilovom da mu nisu pomogle revolucionarne mase, bez boljševika

Kerenskoga bi bio odnio vrag”,20

a ruski boljševizam određuje kao smrt demokracije. 21

Navedeni sukob dviju ideja slavenstva – jugorojalističke i lenjinski nastrojene

komponente – Krleža dokumentira spominjući da s Koraćem (usp.Visković 2001:145) ideje dijele, primjerice, i Zofka Kveder i

Juraj Demetrović, pa tako u Davni danima 1917. godine zapisuje:

Što da odgovorim ovima (Zofka Kveder i Juraj Demetrović itd.) kad psuju po Ruskoj

revoluciji? Svi obožavaju Ruse, a o Rusiji pojma nemaju. Nitko od nas nema pojma o

Rusiji, i kako bih mogao objasniti što hoću reći kad ni ja o njoj nemam pojma?

(Krleža, premaČengić

1982:126).

Inače, Zofka Kveder ima vrlo bitnu ulogu u Krležinu retrospektivnom memoarskom zapisu

Pijana novembarska noć 1918 gdje iz perspektive 1942. Krleža

transformira Salominu i Johanaanovu figuru: referencijskom ovjerom u

zbilji Saloma postaje “dobra Hrvatica i otmjena gospođa jučer, a jugoslavenska demokratska

žena večeras, s jednim jedinim Idealom Dinastije Karađorđevića na pastozno ružiranim

usnama, i to od ove čajanke večeras do prekosutra”, a Johanaan figurira kao krvava

metonimija odsječenih domobranskih glava (DD2, 149). Naime, Salomom, kako je interpretativno

kontekstualizirana u memoarskom zapisu Pijana novembarska noć 1918,

Krleža razobličuje ulogu “tri eshaezijske Ravijojle” (DD2, 142) – Zofke Kveder-Jelovšek-Demetrović,

Zlate Kovačević-Lopašić i Olge Krnic-Peleš – koje su ga tepijane

novembarske noći (13. studenoga 1918) “izopćile iz narodnih redova” (DD2, 163). U bilješci navedenog teksta imenuje

ih trijadnim politoatributima: “tri troimene pik-dame našeg Ujedinjenja god. 1918. Tri

eshaezijske Ravijojle: Slovenka, Hrvatica i Srpkinja”, koje su dočekivale “Aleksandra

Karađorđevića godinama na zagrebačkoj stanici sa svojim protokolarnim

kranjsko-agramersko-sremskim buketima” (DD2,

142;Marjanić 2005:101–140).

I završno pridodajem, što se tiče Krležina Razgovora u Brest-Litovsku

(1918),kako u podrupku zapisa Krleža daje zanimljiv

psihogram Aleksandre Mihajlovne Kolontaj, bilježeći da u trenutku kada se glasalo

da li da se sklopi mir s njemačkim generalštabom ili ne, “Kolontajeva,

kojoj su zatajili živci” “ispala [je] protiv Lenjina sa čitavim nizom grubih verbalnih

injurija” (DD2, 186–187).

Navedeni navod o Aleksandri Kolontaj može se kontekstualizirati i Krležinom ljubavi prema

njoj, o čemu svjedoči i npr. Irina Aleksander, ističući da je Krleža bio zaljubljen u šest

žena, pri čemu navodi svega tri: Aleksandru Kolontaj, Belu i sebe (Aleksander 2007:294), gdje za sebe apostrofira da stoji, na

šestom, posljednjem ljubavnom mjestu.

Inače, do Koraćeve Socijaldemokratske stranke (HSSDS) Krleža dolazi zahvaljujući

revolucionarnoj trojki, “pobunjenoj omladini” (kako ih je označio Josip Horvat) –

Đuri/Đuki Cvijiću, Kamilu Horvatinu i Augustu Cesarcu (Čengić 1982:128;Očak

1982:28–29), koja mu je imponirala zbog toga što su pod vodstvom Luke Jukića

izvršili atentat na bana Cuvaja 1912. godine, što uvodi i u fiktivni svijet svoga

posljednjeg romana.22

I ubrzo Vitomir Korać predlaže Krleži suradnju u svom socijalističkom glasilu

Sloboda (Očak 1982:29).

Naslovnica knjige o radničkom pokretu Vitomira Koraća: Pov[i]jest

radničkog pokreta u Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji.Od prvih početaka do ukidanja ovih pokrajina

1922. godine. Zagreb: Radnička komora za Hrvatsku i Slavoniju u Zagrebu, sv. 1–3,

1929.–1933.

Čitam V. Koraća. Naš Postolar iz Šida ispast će na kraju kao jedini historik (da

ne kažem 'povjesnik', što bi, što se Koraćevih Povjestica tiče, bilo ispravnije)

hrvatskog socijaldemokratskog pokreta. (…) Moglo bi se dogoditi zaista

da Koraćeva pristrana pisanija ostane kao jedini komentar onih dana, a trebalo

opovrgnuti sve njegove blezgarije od prve riječi do konca” (Krleža 1977b:479–480). 23

KRLEŽINE POLITIKE PRIJATELJSTVA

I dok je u razgovoru o Brest-litovskom miru Krleža dokumentirao sukob između

antantofilske inteligencije, u drami Golgota (1923.) dokumentira sukobe u

okviru politika prijateljstva (Usp.Derrida 2001;García-Düttmann

2003) u samom radničkom pokretu. U slobodnoj interpretativnoj mreži značenja

možemo reći da Krležu kao i Derridu zanima tumačenje uzvika “O, moji prijatelji,

prijatelja nema”, što je uostalom i dokumentirao u svom posljednjem romanu – veliko

prijateljstvo između Kamila Emeričkoga mlađeg i Joje. 24

Upravo Krležina drama Golgota (1922.) označava prvi žanrovski okvir

njegove izrazito političke dramaturgije, na što upućuje i njezina posveta: “sjenama

Richmonda i Fortinbrasa”, Shakespeareovim likovima koji nose baklju otpora nasilju (Gašparović 1989:70–71). Nikola Batušić prvi je

upozorio da je prvobitni moto u časopisnoj verziji Golgote slijedio

dedikaciju “Agnus Dei! Qui tollis peccata mundi! Ora pro nobis”, a da je u svim kasnijim

izdanjima ispušten. Riječ je o autorskoj varijanti teksta svećenikova zaziva pri lomljenju

kruha kod katoličke mise, iz čega moto, kao što nadalje utvrđuje navedeni teatrolog,

pokazuje da Krleža od jaganjca Božjeg “nije zaiskao niti da nam se smiluje niti da nam

poda mir, već da moli za nas” (Batušić

2007:231).

Tako u zapisu Premijera “Golgote” 3. XI. 1922. Rukopis od 4. novembra

1922. (DD2, 381–392) 25

Krleža spominje Zofku Kveder-Demetrović u atributivnom određenju supruga i

poetesa Jurja Demetrovića, “poznatog marksističkog ideologa i lidera, danas

prisutnog u svojstvu Kraljevskog komesara kod bivše Pokrajinske vlade”, a koji je bio

uvjeren kako je Golgota,koja je praizvedena u Zagrebu spomenutog datuma u

HNK-u u Gavellinoj režiji,ispisana kao “pamflet protiv njega lično kao socijalističkog

renegata”. 26

U bilješci dnevničkog zapisa Krleža zapisuje kontekst te glasine: “Stvorila se sama od

sebe glasina, a ta je kružila gradom kao što već takve glasine kruže, da se pod krinkom

Kristijana krije Juraj Demetrović, a i on sam bio je uvjeren da je tako” (DD2, 384).

Zamjetno je da dok je Zofku Kveder-Demetrović u memoarskom zapisu Pijana

novembarska noć 1918 Krleža sarkastično označio kao jednu od trikolornih

eshaezijskih Ravijojli, u zapisu o premijeri Golgote očito je da Krleža

povezuje njezina supruga Jurja Demetrovića sa žutom negacijom Krista.

Naime, Golgota dramatizira sukob unutar samoga radničkog pokreta – između

crvene linije radničkog pokreta (Pavle kao prefiguracija Krista) koji

su vođeni idejama Oktobra, i žute, oportunističke linije radništva

(Kristijan kao prefiguracija Jude) koja stremi kao kolumbovska Gomila samo poboljšanju

vlastitoga materijalnog života. 27Golgotu Krleža piše u razdoblju od 1918. do 1920., u doba vlastitog

angažmana u SRPJ(k), poslije KPJ, kada vrlo često nastupa kao govornik na skupovima (Krležijana1:301). 28

Upravo segment dnevničkog zapisa od 23. travnja 1920., Kraljevica,

Brodogradilište(Scena na stanici Kameral –

Moravitz), Nikola Batušić određuje kao kontekstualni okvir trećeg čina

Golgote (Batušić 2002:114).

Pored navedenoga, Krleža u bilješci zapisa Premijera “Golgote” 3. XI. 1922.

Rukopis od 4. novembra 1922. zapisuje kako je Golgotu pisao u

Kraljevici 1920. godine (usp.DD2, 384).

Ukratko, Golgota tematizira stanje u europskom radničkom pokretu nakon

Oktobarske revolucije, sukobe i rascjepe u Drugoj i Trećoj internacionali, a uvodno smo

istaknuli koliko je kriza Druge internacionale djelovala razočaravajuće na Krležu te time

golgotski problem u Golgoti figurira kao etički problem izdaje (Vučković 1986:161). Biblijski arhetip pritom

se rastvara i na primjeru Ksavera (u prefiguraciji Ahasver) koji u kritičnom trenutku nije

pritekao Pavu (prefiguracija Krista) u pomoć, kao što je Ahasver, prema srednjovjekovnoj

predaji, kada je Krist na putu do Golgote zamolio vodu, uskratio mu tu vodu (Ibid. 163;Matičević 1996:129). Navedenim se dobiva sljedeći paralelizam:

Pavle – Krist, Kristijan – Juda i Ksaver – Ahasver te Andrej koji nakon Pavlove smrti

preuzima njegovu, Kristovu ulogu, što upućuje da Golgota pored toga što

funkcionira kao politička drama figurira i kao drama ogoljele ljudske

egzistencije (Gašparović

1989:80), u navedenoj kontekstualizaciji u okviru politike prijateljstva.

ZAKLJUČNO O KRLEŽINOJ DVOSTRUKOJ OPTICI NA BREST-LITOVSKI MIR

Krležini Davni dani, dnevničko-memoarski zapisi, obuhvaćaju, dakle,

kancerozno razdoblje od 1914. do 1921./22. “kada je čitav ovaj blatni pejzaž preletio

anđeo smrti” (DD2, 22), kada se brblja “o oštrim noževima kao o

najsvakodnevnijoj pojavi” (DD, 262). Tako u

povijesnom eseju Prije trideset godina (1917–1947), 29što ga uvodi u dnevničko-memoarsku strukturu Davnih dana, u njegovu

prvu izdanju iz 1956. godine, Krleža detektira kako nema (hrvatskog)

ljetopisa o Prvom svjetskom ratu (DD, 398)

jer – kao što bilježi u dnevničkom zapisu 15. rujna 1916. – riječ je o razdoblju kada su

svi mislioci zatajili, prepustivši se etičko-indiferentnoj šutnji

(DD, 219). Vjeruje kako je

dublji smisao ovih (davnih) dana moguć

samo iz retrospektive (DD2,

39), retrodiskursa neutralizirane, ohlađene povijesti. Posredno

vlastitom dvostrukom optikom na Brest-litovski mir Krleža demonstrira ono o čemu svjedoči

Annika Mombauer u vlastitom proučavanju Prvoga svjetskog rata – da je “povijest uvijek

samo interpretacija događaja, formulirana u kontekstu političkih okolnosti” (Mombauer 2014:259). I završno njezinom

povjesničarskom detekcijom:

Povijest nije objektivni, činjenični prikaz događaja onako kako su se dogodili, a

povijesne analize valja čitati s jasnim razumijevanjem njihovog porijekla. Povijest je

podložna pristranosti, falsifikaciji i namjernom pogrešnom tumačenju pojedinaca, čak i

profesionalnih povjesničara, kao i cenzuri vladinih tijela – ako su rezultati povijesnog

istraživanja previše neugodni ili se previše nepovoljno reflektiraju na sadašnjost. Za

studente povijesti to je možda najvažniji zaključak ove knjige” (Mombauer 2014:259).

U dnevničkom zapisu 28. listopada 1915., gdje Krleža dijagnosticira kako instrumentacije

Julesa Masseneta s Goetheovim motivima još uvijek nisu raskrinkane kao besmisao, ispisuje

apokaliptičnu viziju povijesti: “A ustvari ovako zločinačke, kriminalne, perverzne,

bolesne civilizacije još nije bilo u historiji. Ni jedna nije bila razdirana takvim

protuslovljima” (DD, 57).

U kontekstu navedene dvostruke optike na Brest-litovski mirovni sporazum nastojala sam

dokumentirati i Krležine vizure prijateljstva; i dok u Razgovoru o Brest-Litovsku

(1918) Krleža dokumentira kako je Brest-litovski mir prouzročio političku

dramatizaciju (i) osobnih prijateljstava, dramatsko razdvajanje hrvatske

socijalne demokracije na frakciju koja apostrofira “Rusko Slavjanstvo” ideologema

Kerenskoga, premijera privremene vlade Rusije 1917. godine te na “lenjinski nastrojenu”

frakciju, u drami Golgota (1922.) dokumentira i raspad prijateljstva i u

radničkom pokretu, i time se vraćam na uvodni zapis o politikama prijateljstva kako ih je

dokumentirao Freud 1921. godine u suodnosu bodljikave prasadi.

Inače, dva su stava što se tiče Krležina dokumentarizma Prvoga svjetskog rata, i to

uglavnom iz perspektive njegove zbirke Hrvatski bog Mars (1922.) kao i

njegovih ratnih drama – Galicija (1922.), Golgota

(1922.) i Vučjak (1923.). I dok neki, kao npr.

Filip Škiljan čije mišljenje dijelim, smatraju da je Krleža dao vjerodostojnu sliku Prvoga

svjetskog rata, neki se pak zadržavaju na pitanju stereotipizacije i autorova

ethosa.Naime, Filip Škiljan ističe realan opis u noveli Tri

domobrana (1921.), način na koji su Zagorci doživljavali odlazak na ratište i

eventualni dopust (Škiljan 2014:68). No, Vlasta

Horvatić-Gmaz smatra da je Krleža oblikovao literarni stereotip 30zagorskog domobrana prisilno unovačenog da bi uzaludno ginuo za cara i Monarhiju u

očajnim prilikama u galicijskim rovovima, da domobrani iz novele Bitka kod

Bistrice Lesne (1923.) prerastaju u mit “o neratobornim, nepismenim i

rezigniranim zagorskim domobranima, nemoćnim da promijene svoj položaj” (Horvatić-Gmaz 2014:16). Naime, autorica

zaključuje da Krleža radikalizira protumonarhijska uvjerenja i osobni animozitet prema

austrijskim vojnim strukturama.

Zadržat ću se na pozitivnokvalitativnim određenjima Krležine reprezentacije Prvoga

svjetskog rata s obzirom na stvaralačku slobodu odabira navedene perspektive. Tako

Zvonimir Freivogel ističe kako se u Hrvatskoj sve donedavno relativno malo znalo i pisalo

o postrojbama austrougarske vojske “jer je to znanje, kao i sjećanje sudionika godinama

sustavno 'brisano' iz kolektivne svijesti i povijesti koju su 'skladali' pobjednici. Više

se o austrougarskoj vojsci moglo saznati iz beletristike, poput Hašekovog Dobrog

vojaka Švejka ili Krležinog Hrvatskog boga Marsa nego iz

stručne literature koja za to razdoblje do hrvatske samostalnosti praktički nije ni

postojala” (Freivogel 2014:9).

Irina Aleksander, obično određena prepoznatljivom sintagmom “kontroverzna prijateljica

Miroslava Krleže”, jedna je od rijetkih krležologinja koja je istaknula da Krleža odlazi u

rat kao običan vojnik, da odbija promaknuće u časnički čin: “Ide ratovati rame uz rame s

tim seljacima, otkinutim od rodne grude u ime tuđega rata, s tim 'kandidatima za slavnu,

kraljevsku, mađarsku domobransku smrt'” (Aleksander

2007:195). Ivo Štivičić smatra da je Krležina Kraljevska ugarska

domobranska novela najbolji scenarij napisan na matrici koju Amerikanci

eksploatiraju već punih pedeset godina, a to je kako izdresirati čovjeka da bude poslušni

ubojica. To su sve one, kako Štivičić scenaristički opisuje, “vježbe po štangama pa kroz

vodu, po blatu”. Sve je to Krleža zabilježio u Kraljevskoj ugarskoj domobranskoj

noveli (1921.) koja je “gotov scenarij, a donosi jednu od najčudesnijih i

najužasnijih priča o tome kako se uništava i muči čovjek” (Štivičić 2013). 31

I završno navodim kako je Velimir Visković u predgovoru knjige Krležološki

fragmenti istaknuo da je Krleža permanentno odbijao “ponude da postane

profesionalni političar (i onu Koraćevu iz 1918. godine, kad je trebao postati jednim od

čelnika hrvatskih socijaldemokrata, i onu Brozovu nakon 1948.)” (Visković 2001:6), što se danas nažalost često zaboravlja ili

iz nekog pogleda na svijet (od kojeg je Krležin Doktor iz romana

Na rubu pameti zazirao) prešućuje. A koliko su politike

prijateljstva Krleži bitne svjedoči i Vaništin zapis iz studenoga 1981. godine

kada mu je Krleža, mjesec dana pred smrt, rekao:“Imao sam malo prijatelja, vrlo malo u

odnosu na velik broj ljudi koje sam poznavao. Bili su to Kamilo Horvatin, Cesarec, Vaso

Bogdanov, Krsto [Hegedušić, op. a.],” čime se ponovno vraćam na moto ovoga članka o

bodljikavoj prasadi koja, prema Freudu, može prepoznati istinske granice

prijateljstva.

I shall be considering Krleža’s reaction to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (2 December 1917

– 2-3 March 1918), a peace treaty signed on March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the

Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey – Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) (cf.Mombauer 2014:57,Crutwell 1982:479), in the context of his diary-memoirist entries

titled Bygone Days

1as the only Croatian literary journal from WWI (namely, I do not refer to other

Croatian journals from WWI with literary determinants, as observed by Marijan Matković,

but rather to a literary journal) (Matković 1985:188).2

Milan Vlajčić (1963:588) believes that any

“discussion on Miroslav Krleža should (...) begin with Bygone Days” or a

tautology according to which all Krleža’s works had been hinted at in his

WWI journals, which particularly refers to the “river novel”, his last novel

TheBanners (ibid.:588-589). 3

Hence, Aleksandar Šlivarić suggests that if one was looking for the “embryonic beginning,

a date of birth for the Croatian Rhapsody (Hrvatska

rapsodija) (Savremenik, 1917, 5) then they would do well to

look at the Zagreb – Nova Kapela Batrina – Požega route at the beginning of April 1917”

(Šlivarić 1957:1011), which was recorded in

Bygone Days for the mentioned year.

In the interpretative niche of literary and political anthropology, given that

(auto)biographical contextualization, both centripetal and centrifugal, has become

unappealing to many, due to its stylistic and narratological interpretations, so much so

that there were no Krleža’s biographies beforeLasić’s Chronology (1982), I will be contextualizing the first

year of war (1914) through Krleža’s biographical chronology – Krleža was (only) 21 when

the first diary entry dated 26 February 1914 in his literary journal Bygone

Days contained a fragment of Salome

4, which together with the play Legend (printed in Marjanović’s

Literary News the same year) belonged to Krleža’s first dramatic texts.

THREE WARS AS KRLEŽA’S RITE OF PASSAGE

It is noticeable from the psychobiographical niche that apart from the given historical

and global apocalyptic circumstances, Krleža began to write Bygone Days

after having gone through his personal calvary. Namely, the year of 1913 is crucial for

delineating his life itinerary because it is the year when the idea about escaping the

Hungarian Ludovica Military Academy matured. Krleža had been undergoing the military drill

in Hungarian military academies for five years, namely from 1908 to 1913, from the age of

fifteen to twenty, first as a cadet at the Hungarian Royal Officer Cadet School in Pecs

(1908 – 1911), and then at Ludovica (1911 – 1913) (cf.Zelmanović 1987).5

In addition to the idea of escaping Ludovica, realizing in these formative years that the

military was not his calling, in 1913 Krleža also began to develop an ambivalent political

position, which was in line with his antithetical carousel

6

i.e. a paradoxical mixture of Starčević-esque love for Croatia and a sentimental vision

of South Slavic unification (Lasić 1982:102).

Thus in April 1913 Krleža left Ludovica Academy in keeping with the vision of South Slavic

unification and reached Paris from where he continued on to Skopje via Marseilles and

Thessaloniki, with the intention of enlisting in the Serbian Army as a volunteer at

Bregalnica (Lasić 1982:104), just before the

war between Serbia and Bulgaria started. To be exact, at the time of the Balkan wars (The

First and Second Balkan War 1912 – 1913) Krleža attempted to enlist in the Serbian Army

twice, however in 1912 he was rejected and in 1913 he was suspected of being an

Austro-Hungarian spy and subsequently returned to the Austrian authorities in Zemun. 7

The latter escape almost resembles the sequences from an adventure novel, whereas the

attempt to join the Serbs at Bregalnica bears a resemblance to Melanija’s voyage with

Novak the cavalier, to put the mentioned anabasis in the context of the

fictional world of Krleža’s first novel The Three Cavaliers of Miss Melanija: An

old fashioned tale fromthetime when Croatian Literary

Modernism was dying (1920/1922). Krleža’s experience at Bregalnica brought

about his disillusionment with the political concept of the South Slavic unification

prevalent at the time, which was to be implemented by Serbia – Piedmont: as he realised

that the battle of Bregalnica was “perhaps disproportionately an event more tragic than

this war, because at Bregalnica Dostoyevsky’s prediction came true for the second time:

that all these Balkan peasants would slaughter and kill each other to extinction if they

could lay their hands on cannons!” (BD,

248). Thus Bregalnica destroyed all Krleža’s ideas, illusions

about the Illyrian Movement and, unlike the Austrian Algeria, he came to know the South

Slavic, Serbian Algeria, as an expansionist national force (Lasić 1989:104). In short, in June 1913, after two months of

travelling, he reached Bregalnica where he was awakened from the South Slavic concept of

unification under the Yugo-Royalist views of the Karađorđević dynasty, which was

monumentalized by the Meštrović’s Vidovdan Temple Model. 8Namely, at that time Meštrović’s wooden Vidovdan TempleModel

(1907 – 1912) appeared as the first artistic visualization of the Kosovo Myth

with political subtext of the royalist Yugo-mythos. 9

Hence, in 1913 Krleža returned to Zagreb as a deserter and a definite rift between

father, a clerk in Austria-Hungary (Miroslav Krleža senior) and son

(Miroslav Krleža junior) ensued. To his father Krleža was “a deserter, a

nobody, a crying shame” (1982:109). It is from this position of global and personal

calvary that Krleža began to write his diary-memoirist entries titled Bygone

Days as a “drama with a thousand faces” (Matković 1985:187) – at the age of 21 in the apocalyptic year when WWI

began.

Apart from 1913, the year of 1914 proved in many ways to have been a crucial

turning point in Krleža’s life: the beginning of war and the collapse of the

International which vanished “like an apparition from a spiritualist séance” (BD2, 283). Let us dwell on the collapse of the

Second International. The beginning of the WWI and its infernal simultanism marked the

absolute loss of faith in the Second International on Krleža’s part – “a monumental marble

goddess who, according to Marx, was intended to save Europe from capsizing” (BD, 417) – which, instead of promoting

internationalism, accepted the policy/strategy of defending the singular, national

interests. Therefore, Stanko Lasić interprets the mentioned excerpts as a crucial turning

point in shaping Krleža’s viewpoints, within which he accepts the Leninist version (Lasić 1982:115, 118) of the interastral

barrages (AD, 356; 201).

Let us also dwell on Krleža’s life chronology during the apocalyptic year when WWI broke

out. In August 1914, he received a conscription notice from Austria-Hungary military

authorities asking him to register for recruitment. Since he weighed only 46 kilo, he was

rejected (Krležijana

2::562), an event that Ranko Marinković preserved in literary memory

in a scene depicting Tresić’s recruitment in the novel Cyclops (1965).

Nevertheless, in December 1915 Krleža was conscripted and sent to the Officers’ School for

reservists (25th Home Guard regiment). The barracks were situated in the former school

building in Krajiška Street in Zagreb (Lasić

1982:123, 125). To continue with Krleža’s war biography, which is here mentioned

in fragments according to Lasić’s Chronology (Lasić 1982), he spent 1916 on the Galician Front as part of the

cannon fodder mass (BD, 126; cf. diary entry

dated 17/1/1918) during the first Brusilov’s offensive. During those Galician months,

which are not mentioned in Bygone Days, Krleža had potassium cyanide

pills with him that he procured in Lovran “from an apothecary with whom he became friends,

with the intention of taking them in case he was badly wounded or got in some other kind

of trouble” (Visković 2000:152). From the

fragmented information on Krleža’s life before 1916, it is quite certain that he was

influenced by these three wars (metonymy for “The Grand Master of All Scoundrels”): First

and Second Balkan Wars (1912 and 1913) and WWI, which he often mentioned himself.

In essence Krleža’s Bygone Days can be defined as activist

factual literature on the wartime Oddiseyiad and Penelopeiad. Hence, I

am using the feminine-masculine war binomial from Krleža’s

NovellaMotif (from Bygone Days) about

a girl – who acts as “a kind of Penelope” and realises that all her suitors are pigs – and

her court trainee (cf.BD, 31-32),

particularly according to the entry from the essay Behind the Scenes in

1918, 10

in which he stated that our Penelopes – who are not warriors, but are

waging war nevertheless – do not think that “their Odysseus could return one day, wearing

his laurel wreath” (BD2, 132).

Therefore, while 1913 is a crucial year regarding the rites of passage, provided we apply

Van Gennep’s three phases of rites of passage rituals, Stanko Lasić documents that 1914,

i.e. the collapse of the Second International and the loss of Krleža’s faith in Ilica 55

(social democracy as expounded by Vitomir Korać), is in fact the crucial turning point in

shaping Krleža’s worldview. 11

After providing the context above, I will move on to the interpretation of Krleža’s

Discussion on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a political manoeuvre pro futuro,

from the perspective of 1917.

Ivan Meštrović:wooden Vidovdan TempleModel (1907–1912)

BREST-LITOVSK DISPUTE: LENIN – TROTSKY

The entry Discussion on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) (first

published in Republika, 1967, 7–8) was defined as a polemical dispute, which Krleža was

having “with a typical hanger-on from the Croato-Serbian coalition”,12

who nevertheless later emerged “in one of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes

cabinets as a Minister” (BD2, 179), was

encrusted in diary-memoirist entries of Bygone Days, more precisely in

its second edition, as Krleža’s apologia for peace, i.e. a treaty which Lenin’s Russia had

signed with the Central Powers in order to preserve the October

Revolution. In those bygone days, which were to result in approximately 20 million dead

soldiers and civilians (“WWI”, http), 13Krleža truly believed in Lenin’s interastral barrages, asymptotes of Slavianism

(BD, 356; 201) 14. He pointed out the Russian politosphere, which was the first to refuse

knives (BD, 280–281), as an

ethical and worthy gesture of heritagization, and from the perspective

of 1918 identified the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (3 March 1918) as an anticipation of “the

international solidarity of the European proletariat” given that the mass strikes started

in France and in Berlin (BD2, 188), as a

political manoeuvre pro futuro (BD2, 180).

However, in the footnote to the text, written from the perspective of 1967, Krleža

suggested, as a correction of his own interastral rhetoric, that as early as February 1918

“any Moscow illusion about general strikes in the area of central government, particularly

in Berlin” dissipated under the “terror sewing military hordes” in February 1918, and “the

Leninist concept of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended up in a cul-de-sac” (BD2, 188). Therefore, there are two

perspectives on Brest-Litovsk, one from 1918 and the other from 1967, the latter came

about on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, namely in the

year when Krleža signed the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian

Literary Language (published in a Telegram weekly on 17 March

1967), after which he submitted his resignation from the Central Committee of the League

of Communists of Yugoslavia subsequently withdrawing from public life (Lasić 1982:403). 15

It is also possible to corroborate the above mentioned double vision (1918 – 1967) on the

basis of Krleža’s expressionist play Christopher Columbus (first

published under the title Cristobal Colon in 1918 as part of the book

Croatian Rhapsody, Đorđe Ćelap publishing, Zagreb 1918, together with

the eponymous text and a play Kraljevo) which he originally dedicated to

Lenin only to erase the inscription later on. 16

Namely, he wrote the mentioned one-act play, which discusses the following parallelisms,

spiritual and historical analogies, almost in the sense of Oswald Spengler’s morphology of

the world history: Columbus – Lenin; Santa Maria – Aurora, at the time of the October

Revolution in 1917. A year later, when it was published, he erased the inscription from

it. In the Annotation to Cristobal Colon (Književna

republika, 5–6, 1924) he explains that at the time of writing the one-act play,

a legend, he perceived Lenin in the light of Max Stirner’s (individualist anarchism) and

Mikhail Bakunin’s (collectivist anarchism) two anarchist ideas, which he thematized, for

example, in the play Golgotha (1922) where he demonstrated the

disintegration of the politics of friendship within the workers’

movement. Hence, the Crowd that attempts to kill a Columbian Admiral performatively

elaborates: “We aren’t anarchists like you. We can only be saved by the organization of

work! The Taylor’s system!” whereby the author ironizes the one-dimensional, cyclical

worldview.

Perhaps, he erased the inscription within the context of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty out of

which the Lenin – Trotsky conflict arose.

In this regard, Krleža’s initial perception of Lenin from 1917, when he included him

among the solipsistic views of Stirner and Schopenhauer, is close to Krleža’s imagination

in Salome, from the first diary entry in Bygone Days;

Columbus’ winged ship and his voyage along the tangent into oblivion, towards the stars,

without a compass or a globe, is similar to Salome’s astral strategy – “A woman’s

complexion is of the smallest importance! What’s important are the stars” (BD, 11), or Columbus’ performative utterance:

“The new cannot exist in a circle. The new cannot be about going back”, regarding the

perennial Faustian search for the meaning of human existence.

TWO IDEAS OF SLAVIANISM – YUGO-ROYALIST AND LENIN LEANING COMPONENT

The introduction to the Discussion on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

contains Krleža’s observation of the Coalition’s state of mind in the period

1914–1918, which corroborates that the Brest-Litovsk Treaty had caused political

dramatization (and) personal friendships to dramatically disengage “which

would in the next few months become visible in an irreconcilable struggle and go on to

passionately continue through decades” (BD2,

179) , 17and as an illustration of the schism, the bipolarization of the Croatian social

democracy to the faction which emphasises “Russian Slavianism” of ideologue Kerensky, the

Prime Minister of the Russian Provisional Government in 1917, and the “Lenin leaning”

faction, he wrote a dialogue – duel with a typical coalition hanger-on.

In a nutshell, the mentioned entry confirms Krleža’s private dispute with Vitomir Korać,

whose politics of Yugoslav social democracy frequently abandoned the demands of the

proletariat and agreed to cooperate with the authorities out of interest (Visković 2001:145).

In his introduction Krleža ironically acknowledges the “success” of the Croato-Serbian

coalition in preventing the introduction of a military commissariat in Croatia (in the

period 1914-1918), due to its loyal politics towards Hungarian Government, under the

protectorate of the “Hungarian Prime Minister, count István Tisza” (BD2, 177), given that it had voted for Tisza’s war budget (cf.BD2, 178, 190). However, the real

background to Krleža’s irony was the discovery that the coalition managed to reap

significant profit from the chaos of war for itself, and in order to cover it up as best

it could, it protected “a whole host of secondary citizens’ rights, which was manifested

in the relative freedom of the press and of assembly, which later took on the form of

often challenging anti-Austrian colluding” (BD2,

178). 18

In a footnote to the Discussion, written from the retro

perspective of 1967, uses a predatory zoo-metaphor to corroborate the Central Powers’

politics of cynicism and Machiavellianism which led the concept of the Brest-Litovsk

Treaty into a cul-de-sac: “Turkish, Romanian, Bulgarian, German, and

Austro-Hungarian generals landed in Brest-Litovsk like ravens on the carcass of the

Russian Empire, to snatch Moldavia, the Caucasus, Courland, Lithuania,

Poland, Ukraine, Estonia, Latvia, and Finland from the imperial body” (BD2, 188, italics S. M.). 19

Towards the end of the discussion, he condemns the results/agreements under the Geneva

Convention, by counterpointing the case of Odessa where “our prisoners were being shot

because they did not want to swear allegiance to the King”, while the coalition hanger-on

describes Krleža’s counter-arguments using a political syntagm Viennese

room. In doing so Krleža poses a critical (probing) question:

“Could it perhaps be black and yellow, perhaps I was bribed by Czernin?” (BD2, 191).

The “typical hanger-on of the Croato-Serbian coalition” who remains nameless by the

rhetoric of persuasion and teaching, unintentionally uncovers the politics of cynicism,

macaronic and compromising politics of contradictory

ideologues: as an Entente-phile (Entente-phile Constituents: Lloyd George, Raymond

Poincaré, Georges Clemenceau [cf.BD2,

183]) negates the Junker politics. Nevertheless, he thinks in line

with their logic (Prince Leopold von Bayern [cf.DD2, 182]) apropos the Russian Bolshevism. As

a democrat, he pointed out the champion of the revolutionary democracy Kerensky, who had

the Emperor killed (BD2, 182), however, he

did not understand that Kerensky could never have dealt with “Kornilov had he not been

aided by the revolutionary masses; without the Bolsheviks, Kerensky would have gone to

hell in a handbasket”20

; and defines Russian Bolshevism as death of democracy. 21

The mentioned conflict between the two ideas of Slavianism – Yugo-Royalist and Lenin

leaning components – Krleža shows that for example Zofka Kveder and Juraj Demetrović

shared Korać’s ideas, too (cf.Visković

2001:145) so in Bygone Days in 1917 he wrote:

What do I do with these (Zofka Kveder and Juraj Demetrović etc.) when they curse

the Russian Revolution? Everybody loves the Russians, but nobody has a clue about

Russia. None of us have a clue about Russia, and how could I explain what I mean when

even I have no clue? (Krleža, according toČengić 1982:126).

Zofka Kveder played a very important role in Krleža’s retrospective memoir A

Drunken November night 1918, where he from the perspective of 1942 transformed

the characters of Salome and John the Baptist (Johanaan). Through a referential

verification in reality Salome became “a good Croatian woman and a distinguished lady

yesterday, a Yugoslav democratic woman today, with only one ideal of Karađorđević dynasty

wearing pastel colour lipstick on her lips, from the tea party this evening until the day

after tomorrow”, and John the Baptist (Johanaan) represents a bloody

metonymy for beheaded Home Guard soldiers (BD2, 149). Namely, with Salome, as she was interpretatively

contextualized in a memoir Drunken November night 1918, Krleža

exposes the role of “the three faeries of the Kingdom of SCS" (BD2, 142) – Zofka Kveder-Jelovšek-Demetrović,

Zlata Kovačević-Lopašić and Olga Krnic-Peleš – who on the drunken November night

in question(13 November 1918) “excommunicated him from the commons” (BD2, 163) – “In the note to the mentioned text

he depicts them as a triad of political attributes – “three Queens of Spades of our Union

in 1918 with three different names. Three faeries of the Kingdom of SCS: a Slovene, a

Croat and a Serb woman” – who had welcomed “Aleksandar Karađorđević for years on the

Zagreb Station with their protocol proscribed [derrog.] Slovene-Croat-Serbian nosegays”

(BD2, 142,Marjanić 2005:101–140).

In conclusion, regarding Krleža’s Discussion on Brest-Litovsk (1918) I

would like to add that in a footnote to the entry Krleža gave an

interesting psychogram of Alexandra M. Kollontai, writing that at the

time of voting on whether or not to conclude a peace agreement with the German

General Staff Mrs Kollontai, whose nerves gave out on her, “spoke against Lenin

using a whole array of coarse verbal affronts” (BD2, 186–187).

The above mentioned quote on Alexandra Kollontai can also be contextualized in Krleža’s

love for her, which is confirmed by e.g. Irina Aleksander, who said that Krleža had been

in love with six women, stating the names of only three: Alexandra Collontai, Bela, and

herself (Aleksander 2007:294) and emphasised that she occupied the sixth, i.e. the last

position.

Furthermore, Krleža came into contact with Korać’s Social Democratic Party (HSSDS)

thanks to the revolutionary trio, “the rebelling youth” (as they were described by Josip

Horvat) – Đuro/Đuka Cvijić, Kamilo Horvatin, and August Cesarec (Čengić 1982:128;Očak

1982:28–29), who impressed him because they executed the assassination of count

Cuvaj in 1912 under Luka Jukić’s leadership, which is an introduction to the fictional

world of his last novel.22

Soon after that Vitomir Korać invited Krleža to collaborate on his socialist newspaper

Sloboda(Freedom) (Očak 1982:29).

Cover of the book on workers’ movement by Vitomir Korać: The History of

Workers’ Movement in Croatia and Slavonia. From the beginning to the abolition of

these provinces in 1922. Zagreb: Workers’ Union for Croatia and Slavonia in Zagreb

(Radnička komora za Hrvatsku i Slavoniju u Zagrebu), volumes 1-3, 1929,

1933.

Povjestice

), be more

accurate) of the Croatian Social Democratic Movement. (…) It may well

be that Korać’s biased scribbles remain the only comment of those days, in truth all of

his blather should be refuted from beginning to end (

Krleža 1977b479–480).

23KRLEŽA’S POLITICS OF FRIENDSHIP

While Krleža focused on the conflict between the Entent-phile intelligentsia in the

Discussion on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in the play Golgotha (1923) he

focused on the conflict within the politics of friendship (cf.Derrida 2001;García-Düttmann 2003), in the workers’ movement itself.

Using a free interpretative web of significance we could say that both Krleža and Derrida

were interested in the interpretation of the vociferation “O, my friends, there are no

friends”, which he also depicted in his last novel – a great friendship between Kamilo

Emerički, jr. and Joja.24

Krleža’s play Golgotha (1922) designated the first genre-based framework

of his distinctly political dramaturgy, which is implied in its dedication “To the shadows

of Richmond and Fortinbras”, Shakespeare’s characters who bear the torch of resistance to

violence (Gašparović 1989:70–71). Nikola

Batušić was the first to warn that the original motto in the magazine edition of

Golgotha contained the dedication “Agnus Dei! Qui tollis peccata mundi!

Ora pro nobis”, which was missing from all subsequent editions. The phrase in point is the

author’s version of the words uttered by a priest while breaking the bread in a Catholic

mass which, as the mentioned theatrologist confirmed, shows that Krleža “did not ask from

the Lamb of God either to have mercy or to grant peace, but to pray for us” (Batušić 2007:231).

Therefore, in the entry titled Premiere of “Golgotha” 3 November 1922

(Manuscript from 4 November 1922) (BD2,

381–392)25

Krleža mentioned Zofka Kveder-Demetrović characterizing her as a wife and a

poetess married to Juraj Demetrović, “a well-known Marxist ideologist and

leader, present today in the capacity of the Royal commissar with the former Province

Government”, who was convinced that Golgotha,which was premiered in

Zagreb on the above mentioned date at the Croatian National Theatre, directed by Gavella,

was written as a “pamphlet against him personally as a socialist renegade”. 26

In the note to the journal entry Krleža describes the context of the rumour: “A rumour

has emerged by itself, circulating around the city as such rumours are known to do, that

lurking under the mask of Kristijan was Juraj Demetrović and he himself was convinced of

it” (BD2, 384).

It is worth noticing that in the Drunken November Night 1918 Krleža

sarcastically depicted Zofka Kveder-Demetrović as one of the three-colour faeries of the

Kingdom of SCS, while in the entry about the Golgotha premiere he clearly

connected her husband Juraj Demetrović with the yellow negation of

Christ. Namely, Golgotha dramatizes the conflict within the workers’

movement – between the red workers’ movement line (Pavle

as a refigured Christ) who follow the ideas of the October Revolution, and the

yellow, opportunist workers’ line (Kristijan as a refigured Judas)

whose only aspiration, like the Columbian crowd, is to have better material life. 27

Golgotha was written between 1918 and 1920, at the time when Krleža was

actively engaged in the Socialist Workers’ Party of Yugoslavia – SRPJ(k), later Communist

Party of Yugoslavia, and often spoke at the gatherings (Krležijana 1:301).28

It is precisely the journal entry from 23 April 1920, Kraljevica,

Shipyard (Scene at the Kameral – Moravitz

Station) that Nikola Batušić identifies as the contextual framework to Act

Three of Golgotha (Batušić

2002:114). Apart from this, Krleža mentions in the entry about the

Premiere of “Golgotha” 3 November 1922 Manuscript from 4 November 1922

that he had written Golgotha in Kraljevica in 1920 (cf.BD2, 384).

To sum up, Golgotha thematizes the state of play in the European

workers’ movement after the October Revolution, the conflicts and schisms in the Second

and Third International. As was highlighted in the introduction, the Second International

had a disillusioning impact on Krleža whereby the calvary problem in

Golgotha features as an ethical problem of betrayal (Vučković 1986:161). The Biblical archetype

also spreads out to the example of Ksaver (refigured into Ahasver) who at the critical

moment did not come to Pavle’s aid (refigured Christ) like Ahasver, who according to a

Mediaeval legend, when Christ asked for water on the way to Golgotha, refused to give him

any (Vučković 1986:163;Matičević 1996:129). This yields the following

parallelism: Pavle – Christ, Kristijan – Judas, and Ksaver – Ahasver with Andrej taking

over the role of Christ after Pavle’s death, which indicates that

Golgotha functions not only as a political drama but also as a

bleak human existence drama (Gašparović 1989:80), within the contextualization of the politics of friendship.

CONCLUSION ON KRLEŽA’S DOUBLE VISION OF THE TREATY OF BREST-LITOVSK

Krleža’s Bygone Days, diary-memoirist entries encompass, therefore, the

cancerous period 1914–1921/22, “when the Angel of Death flew over this entire muddy

landscape” (BD2, 22), when people

babbled about “sharp knives as if they were most ordinary things”

(BD, 262). Thus in the historical essay

Thirty years ago (1917–1947), 29

which he added to the first edition of the journal-memoirist structure of Bygone

Days in 1956, Krleža discovered that there were no (Croatian)

annals on WWI (BD, 398), because, as he

wrote in the entry from 15 September 1916, this was the period when all thinkers

failed, having resigned to the ethically indifferent silence (BD, 219). He believed that the

deeper meaning of these (bygone) days was possible

only in retrospective (BD2, 39),

retro-discourse of the neutralized, cooled history. Through his double

vision of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk Krleža indirectly demonstrates that which Annika

Mombauer evinced in her research of the WWI - i.e. that “history is always just an

interpretation of events, formulated within the context of political circumstances” (Mombauer 2014:259). Concluding with her final

historian’s discovery:

History is not an objective, factual representation of events in the way that

they took place, historical analyses are to be read with clear understanding of their

origin. History is prone to bias, falsification, and intentional wrong interpretation by

individuals, even professional historians, as well as the censorship of the authorities

– in case the results of historical research are too unpalatable or adversely reflect

the present. For the students of history this is perhaps the most important conclusion

in this book (Mombauer 2014:259).

In a journal entry from 28 October 1915, where Krleža diagnosed Jules Messenet’s

instrumentations with Goethe’s motifs as not having been unmasked as absurdity, when he

wrote an apocalyptic vision of history: “While in fact history has never seen such a

miscreant, criminal, perverse, sick civilization before. None of them were torn apart by

such contradictions.” (BD, 57).

In the context of the above mentioned double vision regarding The Treaty of

Brest-Litovsk, I intended to document Krleža’s vision of friendship, too. While in the

Discussion on Brest-Litovsk (1918) Krleža showed that the Treaty of

Brest-Litovsk caused political dramatization (i) in personal friendships, a

dramatic separation of Croatian social democracy into a faction that

emphasizes “Russian Slavianism” as propounded by ideologue Kerensky, the Prime Minister of

the Russian Provisional Government in 1917, and a “Lenin leaning” faction; in the play

Golgotha (1922) he depicted the dissolution of friendship within the

workers’ movement itself, which brings me back to the introductory remark on the politics

of friendship as exemplified by Freud’s Porcupine’s dilemma from 1921.

In general, there are two attitudes to Krleža’s documentarism of WWI, mostly from the

perspective of his short story collection Croatian God Mars (1922) as

well as his wartime plays – Galicia (1922), Golgotha

(1922) and Vučjak (1923). While some, like Filip Škiljan, whose opinion

I share, feel that Krleža painted an accurate picture of WWI, others dwell on

ethos. Namely, Filip Škiljan emphasizes that the novella Three

Home Guards (1921) gives a realistic depiction of the way in which people from

Croatian Zagorje perceived going to the front and getting a possible leave of absence

(Škiljan 2014:68). However, Vlasta

Horvatić-Gmaz believes that Krleža shaped a literary stereotype 30

of a Home Guard from Zagorje who was conscripted by force in order to die in vain for the

Emperor and the Monarchy in desperate circumstances in the trenches of Galicia; that Home

Guards from the novella The Battle at Bistrica Lesna (1923) have become a

myth about “non-belligerent, illiterate, and resigned Home Guards from Zagorje, powerless

to change their position” (Horvatić-Gmaz

2014:16). Namely, the author concludes that Krleža radicalises his anti-Monarchy

beliefs and personal animosity to Austrian military organization.

I shall dwell on the positive and qualitative definitions of Krleža’s WWI representation

regarding his creative freedom in choosing the given perspective. Thus Zvonimir Freivogel

points out that until recently relatively little was known or written in Croatia about the

Austro-Hungarian military troops, “because the knowledge, as well as participants’

remembering were systematically ‘erased’ from the collective consciousness and from

history which was ‘composed’ by the winners. One could find out more about the

Austro-Hungarian military from fiction, i.e. Hašek’s The Good Soldier

Švejk or Krleža’s Croatian God Mars than from professional

literature about the period, which practically did not exist before Croatia’s

independence” (Freivogel 2014:9).

Irina Aleksander, who is often perceptibly characterized by the phrase “controversial

friend of Miroslav Krleža”, was one of the few experts on Krleža who underlined that

Krleža had gone to war as an ordinary soldier and rejected a promotion to the rank of

officer – “He goes to war shoulder to shoulder with these peasants who were ripped out of

their native soil in the name of someone else’s war, with these ‘candidates for a

glorious, Royal, Hungarian Home Guard death’” (Aleksander 2007:195). Ivo Štivičić believes that Krleža’s Royal

Hungarian Home Guard novella was the best screenplay written according to the

same template that Americans had been exploiting for fifty solid years, which is all about

how to train somebody to become an obedient killer. “All those” – as Štivičić puts it from

a screenwriter’s perspective – “exercises that involve running over tree trunks and into

water, through mud”. All this was written by Krleža in the Royal Hungarian Home

Guard novella (1921) which is “a complete script, conveying one of the most

remarkable and most horrible stories about how to destroy and torture a human being”

(Štivičić 2013, URL). 31

In conclusion, I would like to mention that Velimir Visković, in the preface to the book

Krležology Fragments, pointed out Krleža had consistently rejected “the

offers to become a professional politician (including one made by Korać in 1918, when he

was to become one of the leaders of the Croatian Social Democrats, and the one made by

Broz after 1948)” (Visković 2001:6), which

is unfortunately often forgotten today or omitted for the sake of a certain

worldview (which Krleža’s Doctor from the novel On the Edge of

Reason would abhor). It can be seen just how important politics of

friendship were to Krleža from Vaništa’s records from November 1981 when

Krleža, a month before his death, told him:“I had few friends, very few in comparison to

the great number of people I knew. They were Kamilo Horvatin, Cesarec, Vaso Bogdanov,

Krsto (Hegedušić, AN)”, which brings me back to the motto of this paper – porcupines

which, according to Freud, can recognize the true boundaries of friendship.