INTRODUCTION

UVOD

Red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) is in many areas of the world ecologically and economically one of the key wildlife species and as such directly and significantly impacts human welfare and ecosystems (Apollonio et al. 2010,Figgins and Holland 2012,Gude et al. 2012). For example, by foraging on plants, defecating, urinating and transporting nutrients, it affects the local availability of nutrients in soil and thus ecosystem productivity (Schoenecker et al. 2002,Mohr et al. 2005,Smit and Putman 2011); red deer is also an important zoochoric species (Malo and Suarez 1998,Oheimb et al. 2005,Iravani et al. 2011), and a key food source for large carnivores (Smietana and Klimek 1993,Hebblewhite et al. 2002, Jedrzejewski et al. 2002). Moreover, red deer is a highly popular game species (Apollonio et al. 2010,Csányi et al. 2014). On the other hand, it may cause severe damage in forestry (browsing, bark stripping and rubbing young trees), and agriculture (grazing on meadows and fields;Gill 1992,Reimoser and Gossow 1996,Verheyden et al. 2006,Mysterud et al. 2010,Marchiori et al. 2012).

The magnitude of red deer impacts on the environment and humans primarily depends on its local population density (Putman 1996,Palmer et al. 2007). The principal factor that determines population density is habitat suitability (Sinclair et al. 2005), which may be in numerous ways affected by humans, both intentionally and unintentionally. In wildlife management, for example, supplemental feeding and other measures are performed to improve environmental carrying capacity, which affects spatial distribution and fitness of red deer (Putman and Staines 2004,Rodriguez-Hidalgo et al. 2010,Jerina 2012). Forestry measures constantly transform forests and consequently (often unintentionally) affect their habitat suitability for red deer (Adamič 1991,Reimoser and Gossow 1996,Kramer et al. 2006,Kuijper et al. 2009). The full extent of anthropogenic factors is usually poorly understood (Weisberg and Bugmann 2003). Therefore it is difficult or almost impossible to properly address them in forest and wildlife management planning. To optimise and rationalise red deer management, it is important to know the impacts of a variety of factors, in particular of the anthropogenic kind, on habitat suitability.

Space use of red deer may be affected by a variety of natural and anthropogenic environmental as well as “historical” factors (events/management in the past). Key factors include topography (altitude, exposure, slope;Debeljak et al. 2001,Zweifel-Schielly et al. 2009,Baasch et al. 2010,Stewart et al. 2010,Alves et al. 2014) and climate (temperature, precipitation, wind;Schmidt 1993,Conradt et al. 2000,Luccarini et al. 2006). Numerous studies have also demonstrated the impact of different anthropogenic factors: a) forest characteristics, in particular proportion of forest in the landscape (Biro et al. 2006,Zweifel-Schielly et al. 2009,Heurich et al. 2015), fragmentation (Licoppe 2006,Baasch et al. 2010,Allen et al. 2014) and internal forest structure (e.g. proportion of individual age classes, conifer/broadleaf ratio;Debeljak et al. 2001,Licoppe 2006,Borkowski and Ukalska 2008,Alves et al. 2014); b) supplemental feeding sites (Putman and Staines 2004,Luccarini et al. 2006,Perez-Gonzalez et al. 2010,Jerina 2012,Reinecke et al. 2014), fields and meadows (Biro et al. 2006,Godvik et al. 2009,Zweifel-Schielly et al. 2009,Perez-Barberia et al. 2013,Lande et al. 2014); c) disturbance factors such as roads and hiking trails (Baasch et al. 2010,Jerina 2012,Meisingset et al. 2013). Among the “historical” factors, present-day space use is probably most strongly affected by past management of red deer, in particular drastic interventions such as eradication or reintroduction of species (Apollonio et al. 2010,Scandura et al. 2014).

Habitat studies of wild ungulates including red deer can generally be divided into small-scale and large-scale studies. Small-scale studies are commonly conducted on small areas (less than one to several 10 km2) and are based on detailed spatial data such as telemetry and pellet group counting (e.g.Luccarini et al. 2006,Lovari et al. 2007, Borkowski and Ukalska 2008,Heinze et al. 2011,Alves et al. 2014). They typically include only few environmental factors with narrow gradients of values (because usually environment does not change drastically over small distances). Therefore they are more locally relevant and should not be extrapolated. On the other hand, large-scale (e.g. regional level) studies are based on rough indicators of population density (e.g. culling), typically referring to large (up to several 10 km2) administrative units (hunting grounds, municipalities; e.g.Mysterud et al. 2002,Merli and Meriggi 2006,Cowled et al. 2009). The limitation of such studies is that they cannot reliably analyse environmental factors which vary at a smaller spatial scale (e.g. internal forest structure). There is, however, an absence of studies combining the benefits of both approaches.

The purpose of this study was to analyse the impacts of environmental and historical factors on spatial distribution and local population density of red deer on extensive area but at a fine spatial resolution, thus combining the advantage of both approaches. With the aim to improve both red deer and forest management, we focused on habitat factors affected by both disciplines.

STUDY AREA

PODRUČJE ISTRAŽIVANJA

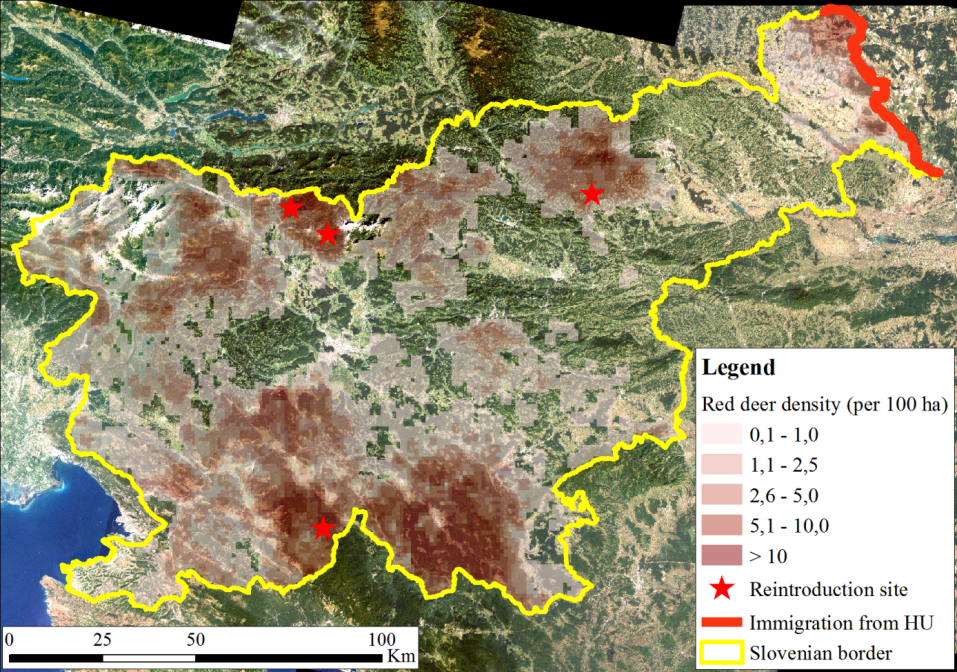

The study area comprises the entire Slovenia (20,273 km2; 45°25' – 46°53' N, 13°23' – 16°36' E), which has very diverse geographical, climatic and landscape features. As such it is also a very diverse red deer habitat, which contributes to the robustness of the study. Average annual temperatures range from 0°C to 14°C and precipitation from 800 mm to 3 300 mm (Ogrin 1996). Altitude ranges from sea level to > 2 500 m high Alpine peaks; 59% of the land is covered in forest; forest cover varies locally from < 20% in predominantly agricultural and urban areas to > 90% in large massifs of Dinaric mountains and Pre-alps (Figure 1;Jakša 2012). Mixed forests are the most common forest type; however, the conifer/broadleaf ratio varies significantly. Common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) are the most abundant tree species, representing 31% and 30% of the growing stock, respectively. They are followed by silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) with 7% and sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) with 6%; individual shares of other species are < 5%. Majority of forests consist of small-scale heterogeneous stands (Jakša 2012). Large even-aged stands (several dozen ha) are rare and typically originate from intensive spruce planting after the World War II (Diaci 2006).

Red deer distribution range covers 60% of Slovenia, its local population densities range from minimal (occasional occurrences) to > 20 individuals/km2(Stergar et al. 2012). In addition to habitat, present-day spatial distribution of red deer is affected by historical factors. In the second half of the 19th century, after the Spring of Nations, red deer was hunted to extinction in Slovenia and in many other parts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. But soon after, at the turn of the 20th century, it was reintroduced at three sites (Figure 1): Snežnik (S), Karavanke (N) and Pohorje (N-NE;Adamič et al. 2007). From these sites and later also form Hungary (NE) it started to expand and repopulate Slovenia. Even nowadays, more than 100 years after reintroductions, red deer is still spatially expanding (Stergar et al. 2009).

Aside from culling, one of the key red deer management measures is supplemental feeding, whose intensity varies strongly between hunting grounds. At hunting ground level (~ 50 km2) the maximum permitted feeding station density is 1/5 km2 or 1/10 km2, but locally it can reach up to 3/1 km2. Red deer is purposely fed throughout winter, but the same stations can be used for feeding of brown bear and wild boar, extending availability of supplemental food throughout the year. Red deer is typically fed a combination of feed: roughage (hay, grass silage) juicy feed (root crops, fruit), and concentrate fodders (maize, grain;Adamič and Jerina 2011,Jakša 2011).

METHODS

METODE

Preparation of data on local red deer population densities

Priprema podataka o lokalnim gustoćama populacija jelena običnog

Our study is based on data with a relatively fine spatial resolution (1 km2) considering the size of the area (the entire country). Estimates of local red deer population densities for all 1×1 kilometre raster cells in Slovenia were obtained combining two well established methods: pellet group counting (Neff 1968,Campbell et al. 2004) and culling density (Imperio et al. 2010,Ueno et al. 2014). The benefits of both methods were utilised: availability of culling density on large area (whole country) and precision of pellet group counting.

All Slovenian hunting grounds systematically record all culling data of ungulate game species with spatial precision of 1×1 km (Virjent and Jerina 2004). Data on all culls in the period 2006-2011 (30 597 culled animals) was used for the analysis. Cull density in kilometre raster cells was used as the baseline indicator of local population density.

Using a sample of 240 plots in 120 1×1 kilometre cells scattered over a large portion of red deer range in Slovenia, we checked the relation between cull density and actual density calculated with pellet group counting. We built a generalised linear model that predicts actual local population density (based on pellet group counts) from different mortality causes (harvest, loss, traffic mortality) in different spatial windows (1×1 km, 3×3 km). Established predictive regression equations were extrapolated to the entire country (described inStergar et al. (2012)).

Preparation of data on environmental factors

Priprema podataka o okolišnim čimbenicima

The study involved a broad range of environmental variables (Table 1) that could potentially (according to the results of previous studies) impact space use of red deer. The data on environmental variables were acquired from publicly available and our own databases.

Due to sex-specific dispersal, red deer spatially expands relatively slow and its expansion in Slovenia is not yet completed (Stergar et al. 2009). Population density at specific location may thus be affected by current habitat factors and management as well as by distance of this location from reintroduction site (and of habitat suitability in between). In addition to habitat variables, we therefore introduced the variable “cost distance”, which for any location within the population area represents the “cost” (difficulty) of migration from reintroduction/immigration site. Since there are four reintroduction/immigration macro-sites, Slovenia was divided into four areas (followingJerina (2006a)). Since it is more difficult for red deer to disperse through more fragmented space (space with lower habitat suitability), the difficulty of migration through each quadrant was arbitrarily assigned an index inversely proportional to the percentage of forest in the quadrant. Quadrants containing human settlements were by default designated as absolute obstacles to migration. Cost distance map was calculated with the CostGrow algorithm implemented in the GIS package Idrisi 17.00.

Baseline values of all environmental variables and variable cost distance were prepared in 1-km2 raster corresponding to the population density data. Actual values of variables used in the analysis were calculated for each cell as the average value of cell and eight neighbouring cells; each cell thus represents the value of the variable for a 3×3 km area. This size corresponds to the average home range size of red deer in Slovenia (Jerina 2006a).

Statistical analysis

Statistička analiza

Dependence between environmental factors, cost distance (independent variables) and population density (dependent variable) was analysed at the level of 1×1 km cells. Due to the specifics of the applied method for determining population densities (seeStergar et al. (2012)) and the averaging of independent variables in the 3×3 km grid, the data were spatially auto-correlated. Potential problems with spatial auto-correlation (Dormann et al. 2007) were avoided by systematically sampling only each central of the 9 neighbouring cells in the 3×3 km grid. Of the 19 746 quadrants entirely located within Slovenia, 2 197 were used for subsequent analysis.

Previous studies (Johnson 1980, Mayor et al. 2009) showed that habitat use is a hierarchical process, occurring at multiple spatial and temporal scales (multi-order habitat use): the first order represents global range of species, the second order local species densities, the third order space use within home range, and the fourth order selection of micro-locations for foraging and other activities. Our study separately examines the impacts of environmental factors on red deer space use of first and second order. In second-order analysis we included broad range of potentially relevant environmental variables, while in first-order analysis we omitted all variables that we assumed cannot impact the global range of the species (e.g. internal forest structure), and variables for which it is impossible to determine whether they are the cause or the consequence of red deer presence/absence (e.g. supplemental feeding).

First-order analysis involved all 2 197 sampled cells, of which 1 335 with red deer presence were used for second-order analysis. At both levels dependence between independent variables and the dependent variable was first checked with bivariate (Table 1) and then with multivariable analysis. At first order we used Point-biserial correlation (Tate 1954) and binary logistic regression (Hosmer et al. 2013) due to the binary dependent variable (red deer present/absent). At second order, where the dependent variable (red deer density) is continuous, we used Spearman correlation and generalised linear models (GLM) with gamma distribution of the dependent variable (Zuur et al. 2009), which corresponds to the distribution of red deer density.

All independent variables were first standardised. For both types of regression models we checked whether the relationships between the independent variables and the dependent variable were linear. The variable temperature was found to relate nonlinearly, thus square transformed temperature was additionally included in the model. To avoid multicollinearity, we: a) first calculated Spearman correlation for pairs of independent variables; if the absolute value of the correlation coefficient was > 0.6, the variable with the assumed ecologically less meaningful impact on red deer presence/density was excluded, and b) additionally excluded the variables with variance inflation factor > 3 (Zuur et al. 2009). After multicollinear variables were excluded, the final selection of variables was made for both types of models (Table 1). We calculated all possible models and explored the structure of all candidate models with ΔAIC scores ≤ 2 and used them for model averaging to obtain robust parameter estimates (Burnham and Anderson 2002). All statistical analyses were conducted with R ver. 3.0.2.

*Variable not included in baseline selection in this analysis.

*Varijable koje nisu uključene u polazišnom izboru u ovoj analizi

RESULTS

REZULTATI

According to the Akaike information criterion, red deer presence/absence is best explained by two logistic regression models (ΔAIC≤2). The models predict that the probability of red deer presence depends on share of forest (FOREST, positive correlation), cost distance (COST_DIST, negative correlation) and size of largest forest patch (F_PATCH, positive correlation); the second best model also includes density of forest edge (F_EDGE, negative correlation;Table 2).

According to the Akaike information criterion, local red deer densities are best explained by four models with ΔAIC≤2 (GLM) including following variables: distance to nearest supplemental feeding site (FEED_DIST, negative correlation), cost distance (COST_DIST, negative correlation), size of largest forest patch (F_PATCH, positive correlation), share of spruce dominated pole-stage (F_SPRUCE, positive correlation), density of forest edge (F_EDGE, negative correlation), proportion of forest (FOREST, positive correlation), and ambient temperature (TEMP, first ascending then descending). Two of the four models also involve slope (SLOPE, negative correlation) and share of mast-producing broadleaves (F_MAST, positive correlation;Table 3).

*For the variable temperature (TEMP) the model also included the squared transformation of the variable (TEMP×TEMP). Positive estimate of variable and negative estimate of squared variable mean that red deer density initially increases with increasing temperature and then starts decreasing. Direct comparison of impact of temperature with other variables is not possible.

*Za varijablu temperatura (TEMP) model je uključivao i kvadriranje varijable (TEMP×TEMP). Pozitivna procjena varijable i negativna procjena kvadrata varijable znače da se gustoća jelena običnog prvotno povećava s povećanjem temperature, nakon čega slijedi pad. Direktna usporedba utjecaja temperature s drugim varijablama nije moguća.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

RASPRAVA I ZAKLJUČCI

Our study demonstrates that red deer local population densities are under strong impact of present-day wildlife management measures (e.g. the impact of supplemental feeding) as well as forestry measures (e.g. proportion of stands of certain age-class and tree species composition). Both local densities and, to an even greater extent, presence or absence of red deer, are also impacted by historical circumstances: past red deer management (eradication and reintroduction) and past land use, which is reflected in present-day forest cover and fragmentation of forest.

Recognising the impact of historical factors helps us understand past dynamics of red deer populations and predict potential future spatial distribution of the species. Dispersal from reintroduction and immigration sites still impacts red deer spatial distribution in Slovenia despite having started 100 years ago. We can therefore assume that the locations of reintroduction sites have been the main factor determining the course of dispersal and repopulation of the country by red deer, following its reintroduction. This factor will remain important in the future, as spatial expansion of species has not yet been completed (Stergar et al. 2009). The importance of share of forest cover and its fragmentation (for habitat suitability) shows that past land use, in particular the abandonment of agriculture and spontaneous afforestation of agricultural land in the 20th century, significantly contributed to the red deer population dynamics (Adamič and Jerina 2011). The situation is very similar to the majority of European countries: the imminent extinction of red deer was followed by reintroduction or immigration in the 19th and 20th century, which led to gradual population increases. In the subsequent decades the abandonment of agriculture further contributed to increasing population trend of red deer and other ungulates around Europe (Apollonio et al. 2010, Scandura et al. 2014).

Aside from past human activities, local red deer population densities are significantly influenced by our present-day interventions, in particular wildlife and forest management measures. Unlike past activities which we cannot influence, present-day management measures can be adjusted at will to achieve the desired impacts on red deer and, consequently, on the environment. The biggest limitation thereof is the often poor knowledge of the strength and complexity of the impacts these measures have on red deer, rendering it difficult to properly target them (Putman 1996,Weisberg and Bugmann 2003).

The inherent complexity of direct and indirect effects of supplemental feeding on red deer is a typical example. Hunters across Europe feed red deer with the aim to attract it and increase its fitness and trophy value. Researchers and forest managers, on the other hand, consider the measure highly controversial due to the potentially undesired impacts on forest (Putman and Staines 2004,Milner et al. 2014). Feeding undoubtedly impacts space use of red deer; numerous studies showed that red deer intensely use supplemental feeding stations and their surroundings and that supplementary feeding reduces annual home ranges of red deer (Luccarini et al. 2006,Perez-Gonzalez et al. 2010,Ferretti and Mattioli 2012, Jerina 2012, Reinecke et al. 2014). The results of our study indicate that the impact of feeding stations is even much broader: they increase densities at the meso-population level as well, thereby augmenting the environmental impacts of red deer. Probably the most common negative impact of feeding is over-browsing and bark stripping in the vicinity of feeding stations, which has been shown by several studies (Ueckermann 1983,Schmidt and Gossow 1991,Nahlik 1995). Red deer which visits feeding stations almost never consume exclusively supplementary feed, but also forages natural vegetation in the vicinity (up to several 100 meters) of the feeding stations to balance their dietary needs (Adamič 1990,Schmitz 1990).

Supplemental feeding is often practised to increase animals’ trophy value and fitness, but the results are often the opposite from expectations of hunters and wildlife managers. Whereas few studies have shown positive impacts of feeding on red deer fitness and others have not detected any impacts, numerous studies even demonstrated negative impact on red deer body mass and in some cases even increased mortality as a consequence of supplemental feeding (for review seeMilner et al. (2014)). High density of red deer at supplemental feeding stations can strongly increases intraspecific competition for food. Especially females and younger animals visiting feeding stations are often displaced by stags, which undermines the fitness of these social groups (Wiersema 1974,Schmidt 1992,Seivwright 1996,Putman and Staines 2004). Another cause of decreased fitness and higher mortality is facilitated transmission of disease and parasites among individuals due to their high concentrations at supplemental feeding sites (Hines et al. 2007,Cross et al. 2010,Scurlock and Edwards 2010).

Whereas wildlife management measures are targeted at improving red deer habitat, forest management measures are predominantly aimed at wood production; their impacts on red deer, and indirectly on forest, are often completely overlooked. By changing the age-class ratio and tree species composition, forestry impacts key components of red deer habitat suitability: food abundance and presence of security and snow interception cover (Adamič 1990,Reimoser and Gossow 1996,Kramer et al. 2006,Kuijper et al. 2009,Heinze et al. 2011).

Similar as in past studies, bivariate correlation in our study indicates a positive impact of forest regeneration abundance on red deer density. In accordance with the optimal bite selection theory, which states that diet selection is affected by quality as well as abundance of food (Iain and Herbert 2008), red deer often concentrates in forest regeneration gaps (Reimoser and Gossow 1996,Kuijper et al. 2009). However here, unlike in the case of concentrations at feeding stations, the effect on regeneration capacity of forest is in general favourable. In larger regeneration gaps (and in sylvicultural systems with larger proportion of regeneration areas) red deer is practically saturated with food, therefore it cannot compromise successful recruitment of young growth (Storms et al. 2006). At the same time regeneration gaps attract red deer from parts of forest with more dispersed regeneration which is more exposed to browsing (Stergar 2005,Jerina 2008). In general, for successful mitigation of negative impacts of ungulates on forest, wildlife management as well as forest management measures have to be adjusted accordingly: sufficient presence and abundance of forest regeneration and selection of a sylvicultural system that provides herbivores with more food and consequently reduces browsing.

In addition to forest regeneration gaps, red deer also selects spruce-dominated pole stands as shown in our analysis, however the effect on forest in this case is completely opposite. Spruce pole stands are very appealing, but at the same time a poor-quality habitat, i.e. an ecological trap (Adamič 1990,Reimoser and Gossow 1996). Snow interception and favourable thermal cover make spruce-dominated pole stands popular wintering areas for red deer, but since the availability of food in such stands is very low, red deer are forced in extreme winters to consume bark of young spruce, which is often the only available food (Gill 1992,Völk 1999,Ueda et al. 2002). Stands planted on abandoned grassland and pastures, especially those on humid sites where spruce is particularly susceptible to disease, are especially vulnerable. When supplemental feeding sites are located in the vicinity of such stands, the damaging impacts accumulate, which may result in completely destroyed stands (Čampa 1986). Increased culling of red deer is commonly considered the first and only measure to prevent or reduce bark stripping (Putman 1989). Studies however indicate it is often ineffective, as red deer can cause massive bark stripping even at very low densities (Völk 1999,Verheyden et al. 2006). It is more effective to avoid creating such spruce plantations in the first place (Vospernik 2006) or to systematically reduce their favourable cover conditions for red deer by carrying out intensive thinning, which reduces interception of snow and increases its ground thickness. At the same time, more radiation increases bark roughness, which reduces its attraction and accelerates radial growth, and consequently reduces the time such stands are exposed to back stripping (Vospernik 2006,Jerina et al. 2008, Mansson and Jarnemo 2013).

Indirect impacts of wildlife and forest management measures on red deer habitat use within their home range have been confirmed by several studies. Our study is one of the first to demonstrate the impacts of wildlife and forest management measures also at the population level, which suggests that the impacts of the studied factors are much broader and more complex than typically assumed. Neglecting these impacts is therefore particularly damaging, for both red deer and the environment. Wildlife and forest management measures, which impact red deer, also indirectly affect the forest. Measures in both disciplines must therefore be planned in a coordinated manner (Gerhardt et al. 2013). When planning placement of supplemental feeding stations, the distribution of forest stands should be taken into account. The most vulnerable stands – regenerated areas and spruce-dominated pole stands – must be avoided. Feeding can negatively impact red deer fitness and is also a relatively expensive measure (Putman and Staines 2004,Milner et al. 2014). The intensity of feeding should therefore probably be reduced in certain areas. Instead, improvement of more natural resources for wild ungulates can be used as in middle European forestry practise (Weis 1997,Prien 1997). These measures can be implemented through making remises for wild ungulates on deforested land inside, or around forest stands (open strips, brackets, abandoned pastures and meadows etc.). In some parts of Slovenia there is a distinct lack of young growth and regeneration is dispersed, which leads to browsing problems (Jerina 2008); more young growth in large regeneration gaps would mitigate the problem. Pure spruce stands on non-native growing sites are susceptible not only to bark stripping but also to bark beetle outbreaks, fungi and windbreak (Diaci 2006). In Slovenia, intensive planting of spruce is a thing of the past, but in some other European countries the practice remains widespread and should be revised due to the negative impacts associated with red deer.

The results of studies such as ours can be useful directly in wildlife management planning, for example in habitat ranking of hunting grounds. Some European countries, including Croatia, use habitat ranking of hunting grounds for planning of hunting quotas, although the practice is in other countries generally being replaced by more modern methods of adaptive management. Habitat ranking (determining the expected habitat suitability for each species in the hunting grounds) is based on expert knowledge of the species and its habitat preferences (Apollonio et al. 2010,Morellet et al. 2011). Our study, on the other hand, quantitatively evaluated the impact of individual environmental factors on red deer habitat suitability, which could be used for the habitat ranking of given hunting ground. Since the environmental factors were studied at country level, their local effects can deviate from our estimates, which can therefore only be considered as average approximations to reality. In this sense the results of our study underline a shortcoming of habitat ranking: the method assumes that expert knowledge can always and everywhere be applied to reliably evaluate habitat suitability and target densities of red deer or other wild animals. However, this is difficult even with modern analysis of large sets of empirical data.