INTRODUCTION

Values are an important aspect of every society, and they create people’s attitudes and behaviour. Hence, the objective of this study is to research how much power as a social value in general, power in the sense of domination and power over natural and social resources is important to students in Southeast Europe in relation to other motivational types of values from Schwartz’s model. It is also the objective to determine whether the power in general, power in the sense of domination and power over natural and social resources differ among countries. The sample of students is important because they are young people whose habits can still be varied through various social policies and educations, and it is therefore very important to research this population and their values. This article is special because it presents the results of student research in seven Southeast European countries where such research is lacking. INTRODUCTORY DELIBERATIONS ON THE CONCEPTS OF VALUES Man has all through the past always been occupied by the concept of values, trying to name socially acceptable values, to understand and define them. With the Modern Age establishment of different scientific paradigms within the framework of individual social and humanistic sciences, there have been different definitions of the term of values. So philosophy describes values as general characteristics or value terms attributed to individual bearers of values or assets in the process of evaluation, humanities describe values as goals or purposes of action, psychology and sociology as characteristics of thinking, also attitudes, convictions, opinions or actually psychological dispositions and subjective orientations towards values, while pedagogy defines values as normative cultural assets (as norms, ideals, guiding principles, beliefs or moral norms)[1]. The issues of values are also dealt with by other social sciences as anthropology, political sciences and economy, within the context of their respective field of research. So are values “an set of general convictions, opinions and attitudes on what is correct, beneficial and desirable, and which is created through a process of socialization”[2 ; p.500]; p.500 or, according to Shalom H. Schwartz, values are “desirable goals of various significance that transcend specific situations, and act as guiding principles in a man’s life[3]. Schwartz also developed an abundant instrumentation for measuring the system of values, and, alongside Schwartz’s model of norms activation as a concept of determining values, today is the system of values worldwide determined and measured in accordance with the Inglehart’s concept of postmaterialism[4]. Inglehart’s model is based on the thesis that value orientations (traditional, modern and postmodern or postmaterialist) are subject to political and economic development, and in accordance with Maslow’s theory of satisfying human needs, which explains the hierarchic constitution of various human needs: postmatierialist higher-order needs will appear only after the satisfaction of lower-order needs (material needs)[5]. Schwartz’s model is linked to the ability of an individual’s altruistic behaviour, which is determined by personal and social norms as well, and so it will be explained[6] as a sense of moral duty that a person possesses while aiding another human being. In the theoretical part of this article, various sociological concepts of the value power have been thematised as well as Schwartz’s concept of the system of values and motivational type of value power based on it, and it finishes with the overview of relevant research of the systems of values for different populations of subjects from seven countries of Southeast Europe (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, Slovenia and Serbia). POWER AS A PART OF CONSTRUCT OF UNIVERSAL HUMAN VALUES Power is one of the most important theoretical concepts in sociology, but there are also other social sciences dealing with that concept. The most significant sociologist dealing with this concept must have been Max Weber, who defines power as “chances of one person, or a particular number of people, to exercise one’s will within the common course of action, even despite the resistance of others participating in that course of action”[7 ; p.589]; p.589. In the discussion on power in the national sociology, J. Županov surely takes the lead. In his book After the Flood, Županov[8; p.p. 70-71]discusses social and political changes in Croatia after the breakup of Yugoslavia in the context of privatisation. The author initially lists two kinds of power – the power over someone and the power for something, and accordingly also two types of participation in power. The first type is the so-called negative participation in power, in the way that the power of one results in the complete taking of power from the other, so the result would be a complete blockage of the other. The second type of power for something is the equal participation in the decision-making process. Županov also mentions the fake participation, which should be distinguished from the “real” one because it actually represents manipulation and is ideologically marked. Ultimately, Županov wonders whether privatisation presents a transition from the system of power to the system of private ownership or it is just a transition from one type of power to the other. If it is the latter, Županov states: “If privatization is just a substitution of politocratic power by a private economic power, then the social democracy in countries in transition should not be oriented towards the “ownership democracy” or “national capitalism” but towards getting their share, i.e. participating in power[8; p.70]. Schwartz’s model of universal contents and the structure of human values as motivational actuators of a man or guiding principles resides on a theoretical concept assorting all values into one of ten motivational types of values: universalism, self-direction and benevolence, security, conformity, hedonism, stimulation, achievement, tradition and power. Shalom H. Schwartz’s measuring instrument Portrait Value Questionnaire, which measures the proportion and hierarchy of basic human values, has turned out to be reliable and effective for international research of personal and social values[9][10]. The latest version of this scale is PVQ-RR scale assessing ten basic and 19 specific values[11]. Ten already mentioned types of values are linked by motivation stemming from three basic conditions, i.e. from biological needs, the need for coordinated human interaction and the need to function and remain within one’s own social group[6]. As shown in Table 1, Schwartz’s model encompasses ten different types of basic values and 19 values stemming from them. The value of power comprises two specific values: power as domination and power over resources. Power as domination is defined as “power through significance of exerting control over people”, and power over resources is defined as the “significance of controlling material and social resources”[11]. Based on various international samples, Schwartz[11] comes to the conclusion that power over resources applies to material resources and the protection of wealth “regardless of how power is exerted in a society”[11; p.19], while the value of power as domination is “focused on exerting one’s own power over others and the way power is distributed and used in a society”. According to the example of the author[11; p.p.32-33], the person that holds the power of domination as important would exhibit the particular behaviour of “Manipulating others to gain what they want”, while the person holding the power over resources as important would exhibit the behaviour of “Mentioning to others how valuable some of his/her possessions are”. Schwartz[12][13][14] defines the motivational type of value power as a social status and prestige, control and domination over people and resources, with following specific values: social power, wealth, social status, authority, preserving the public image of an individual.

Previous research of Schwartz’s values has shown that it is more important to men to have power over resources than to women. On the other hand, it is more important to women to have power in form of reputation. It is important to point out here that reputation as a value had until recently been a part of the value of power alongside the power in form of domination and power over resources. However, research has shown that it is more appropriate to observe reputation as a specific value[11]. We should also point out that numerous studies have shown that alongside the higher socioeconomic development and a higher degree of the democratisation of a society there is the decline in importance of values conformity, security, tradition and power[15].

RESEARCH OVERVIEW

In spite of the large scientific reception of Schwartz’s theory of universal concepts and structure of values and the research fertility of instruments developed by Schwartz (Schwartz Values Survey – SVS and Portrait Values Questionnaire – PVQ), in the countries of Southeast Europe whose student populations took part in this research, we have observed no wide application of these instruments. In the Republic of Croatia, as well as in other countries of Southeast Europe, a cross-national and longitudinal World Values Survey – WVS[16] is being conducted, and there is information available to the interested public on values of each of the observed national populations, alongside the possibility of their comparison. The research comprises different dimensions of the reality of life, and the subjects from the Republic of Croatia choose as the most significant values in their life family values (99 %), and afterwards the values related to friends and acquaintances (96 %), free time (92 %), work (90 %), religious values (65 %) and eventually to policy (23 %). The comparative analysis of the results of the three researching waves in the concerned study from 1999, 2008 and 2017/2018 points to the declining trend regarding values related to religion and policy and there is the decrease of the significance of values related to family, friends and acquaintances and free time, which points to the contemporary value orientation of man towards materialistic and post-materialistic dimensions of values in relation to the traditional dimension of values[16]. By the comparative analysis of the results of the studies from 1986, 1999 and 2004, Ilišin[17] determines that the value orientations of the youth as well as those of the older population are mainly stable and that young people atribute grater significance to the area of post-materialistic values, while the older population is more inclined to the traditional ones. The research involving the population of Croatian students (N = 759) was also conducted by Mrnjaus[18] and she compared it to the system of values of Austrian students (N = 855), and the research was conducted by the questionnaire used in the World Values Survey – WVS. The values related to family, friends, education, free time and work are the top priorities of both Austrian and Croatian students[18]. By using Schwartz’s SVS questionnaire, Ferić[19] conducted a research on a student population and established that the highest estimated values were reached for the values of self-direction and benevolence, and the lowest for the values of power and tradition. On the territory of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina the research was conducted on the population aged between 18 and 27 (N = 545) using the SVS questionnaire, and students made up 70,3 % of the total number or 383 subjects[20]. In the Republic of Serbia following hierarchy was found: benevolence, universalism and self-direction as the most prominent values and as the least prominent stimulation, power and tradition[21] in the population of students – future teachers. By using the OVQ questionnaire on the population of future pre-school and school teachers (N = 232), Marušić-Jablanović[22] also determined the highest exhibited values for benevolence, self-direction and achievement and the lowest exhibited values for conformity and power. Subjects from Slovenia (N = 1481) and Hungary (N = 1500) took part in a large cross-national research involving almost 30 000 subjects from 20 countries around the world, and the research was conducted using the PVQ questionnaire[23]. But the tested population was aged 15 and higher so we have neither the data concerning the population of students nor the hierarchy of values for individual national population at our disposal. Nevertheless, the researchers state that the value orientation of subjects, which is in congruence with the expectations, in the former countries of the communist regime (as Slovenia and Hungary) is nearer to the conservative orientation (tradition, security and conformism) and the orientation of self-enhancement (achievement and power), as opposed to other tendencies of self-transcendence and openness to change[23]. For the area of Montenegro there was no adequate data found, and for the population of students from the Republic of North Macedonia, the research was conducted on the total of 226 subjects and as the least prominent values there were tradition and power[24]. A relatively small number of studies of the value systems of students in observed national populations points to further need of conducting similar research because the systems of values of younger population point to trends and future value orientations of the entire population[17].

OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESES OF THE STUDY

The objective of this study is to research how much power as a social value in general, power in the sense of domination and power over natural and social resources is important to students in Southeast Europe in relation to other motivational types of values from Schwartz’s model. It is also the objective to determine whether the power in general, power in the sense of domination and power over natural and social resources differ among countries. Considering the objective of the study, following hypotheses have been constructed: H1: power in Southeast Europe takes lower ranking position than other values, H2: power as value in Southeast Europe is different for individual countries.

METHODOLOGY

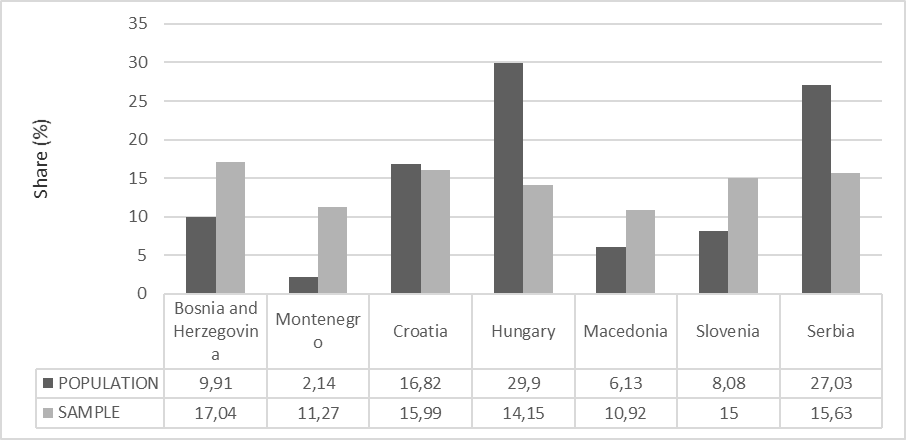

The study was conducted within the project Research on frequency and readiness of students in post-socialist countries of Southeast Europe to report criminal offences, which has won the first prize at an international competition organized by the American Society of Criminology for the best student scientific research project in 2018. A quantitative method of a survey was used in the study, and the data were gathered by an online questionnaire. The participants in the study had been recruited through social networks. The reason for such gathering of data is that online surveying has turned out to be the best method of collecting data when we talk about the student population[25; pp.25-26]. RESEARCH INSTRUMENT The questionnaire contained questions on sociodemoFigureic characteristics and the PVQ-RR scale on values. The PVQ-RR scale of values had, according to Schwartz[11], 57 statements i.e. descriptions of different people where the participants in the study had to answer to what extent they are similar to the described person, on the scale from 1 to 6, where 1 means “not like me at all”, and number 6 “very much like me”[11]. Using the scale of Shalom H. Schwartz, 10 basic values were examined as well as specific values power as domination and power over resources. Basic values with pertaining levels of reliability (Cronbach α) are: self-direction (α = 0,822), stimulation (α = 0,653), hedonism (α = 0,706), achievement (α = 0,652), power (α = 0,84), security (α = 0,801), conformity (α = 0,806), tradition (α = 0,729), benevolence (α = 0,85) and universalism (α = 0,85). Specific values that had been tested were power as domination (α = 0,793) and power over resources (α = 0,796). SAMPLE The study was conducted on an appropriate sample of 1419 students during February and March 2019 in 7 states – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, Slovenia and Serbia. Figure 1 shows the share of students per state in the sample and population. The appropriate sample of 1419 students contained people of both genders, different areas and years of studying, the state of residence, size of the place of birth, socio-economic status, denomination and religiousness.

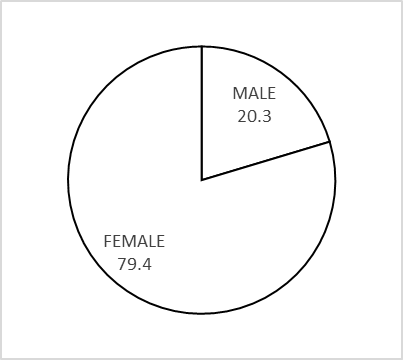

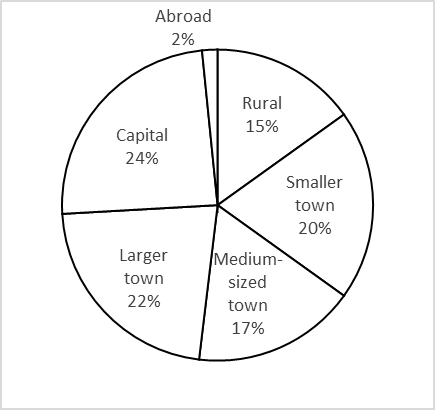

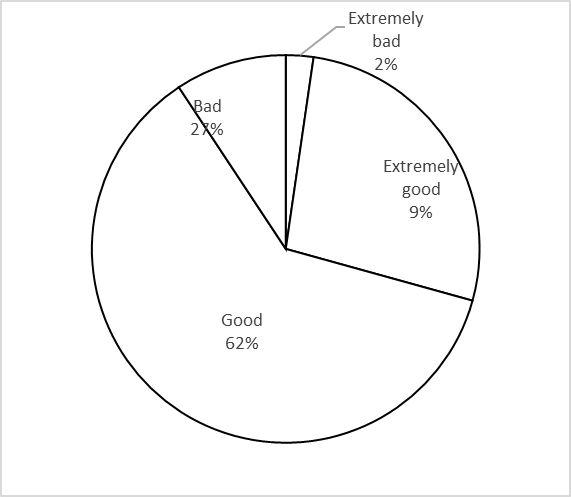

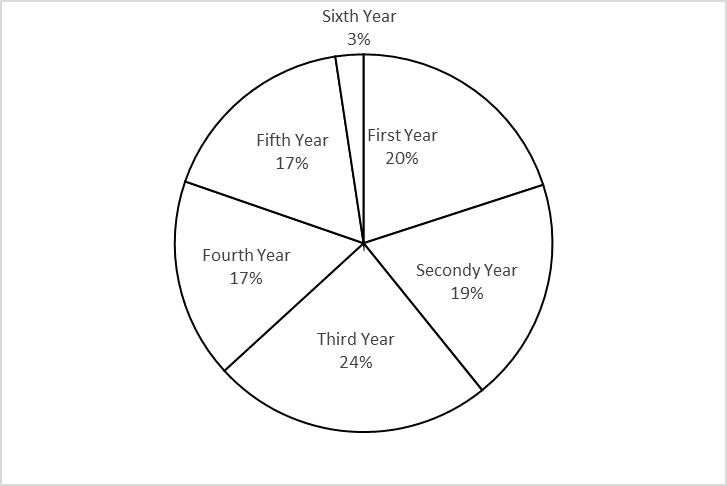

Figure 2 shows how the sample was comprised mainly of people of female gender (79,4 %) while people of male gender were fewer in number. The size of the place of birth was equal in proportion for all categories, where somewhat more participants were born in a capital city (Belgrade, Budapest, Ljubljana, Podgorica, Sarajevo, Skopje, Zagreb), while the smallest number were born in the rural area (15 %) and abroad i.e. out of the SE Europe (2 %), Figure 3. The participants in the research mainly describe their financial situation as good (62 %), and those describing it as extremely bad (2 %) take the smallest share, Figure 4. The years of studying are also equally represented. The most participants are in the third year of study (24 %) and the fewest are in the sixth year (3 %), which can be explained by the fact that the majority of studies in researched states last up to five years, while a few last six years, Figure 5.

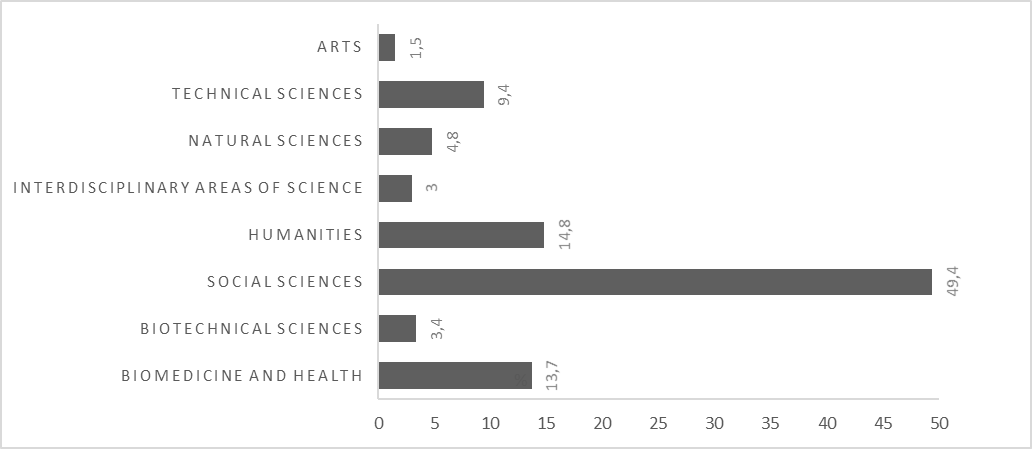

The participants in this research are mainly studying in the area of social sciences (49,4 %) and humanities (14,8 %), in the area of biomedicine and healthcare (13,7 %), then in the area of technical sciences (9,4 %), natural sciences (4,8 %), biotechnical sciences (3,4 %) and in the interdisciplinary area (3 %), while the smallest share is in the area of art (1,5 %), Figure 6.

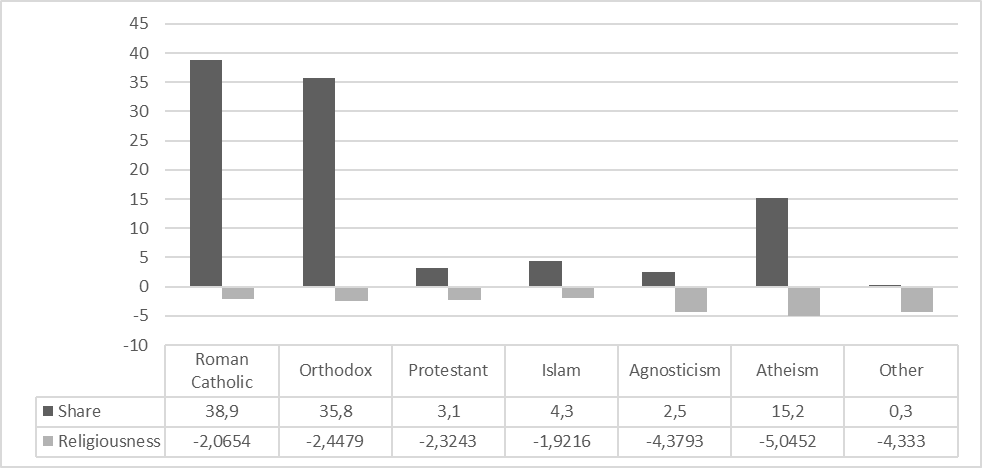

Considering the fact that the study was conducted in culturally different areas, it seems important to underline the structure of denomination and religiousness. In the sample, the largest number state their belonging to the Roman Catholic (38,9 %) and Orthodox Church (35,8 %), after that a somewhat smaller share is made up by Atheism (15,2 %), Islam (4,3 %), Protestantism (3,1 %), Agnosticism (2,5 %) and other (0,3 %). In Figure 7, we can see that the greatest religiousness is exhibited by the followers of Islam and Roman Catholicism, while the smallest religiousness is exhibited by atheists.

STATISTICALS METHODS When analysing the data, descriptive and multivariate statistical analyses were used, and the data were analysed using the IBM SPSS software. The results were corrected according to the recommendation of the author of the measuring instrument, S.H. Schwartz[11], so the values were centred in such manner that the average value of all items of the research participants was subtracted from each social value of a participant. The answers of the participants who had answered to more than 49 items with the same answer i.e. the ones who had not completed the questionnaire in full (less than 50 %) were also taken out from the sample. In this study descriptive statistics (percentages, frenquencies, ranks, mean) and MANOVA and ANOVA were used (Multivariate test, Levene’s test for homogenity of variance, Games-Howell post hoc test).

RESULTS

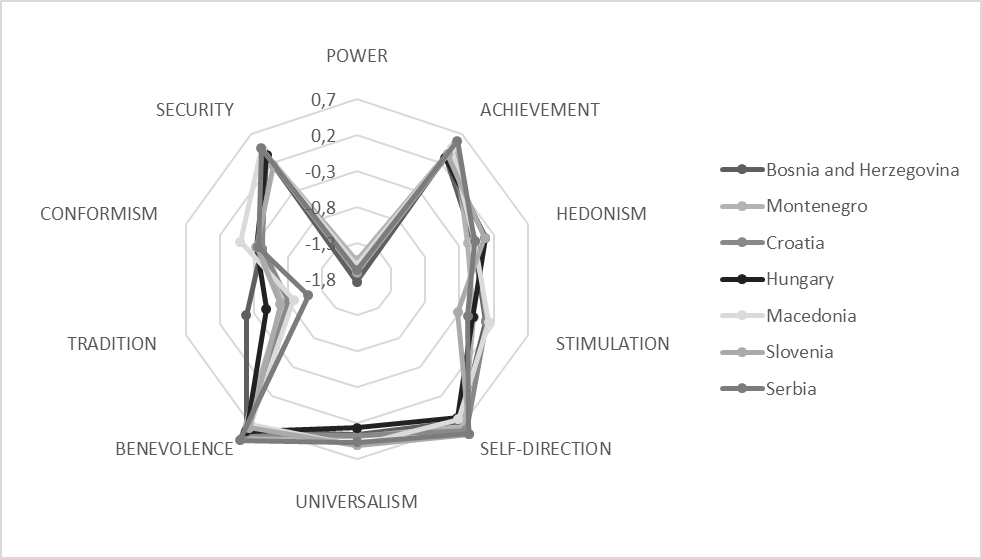

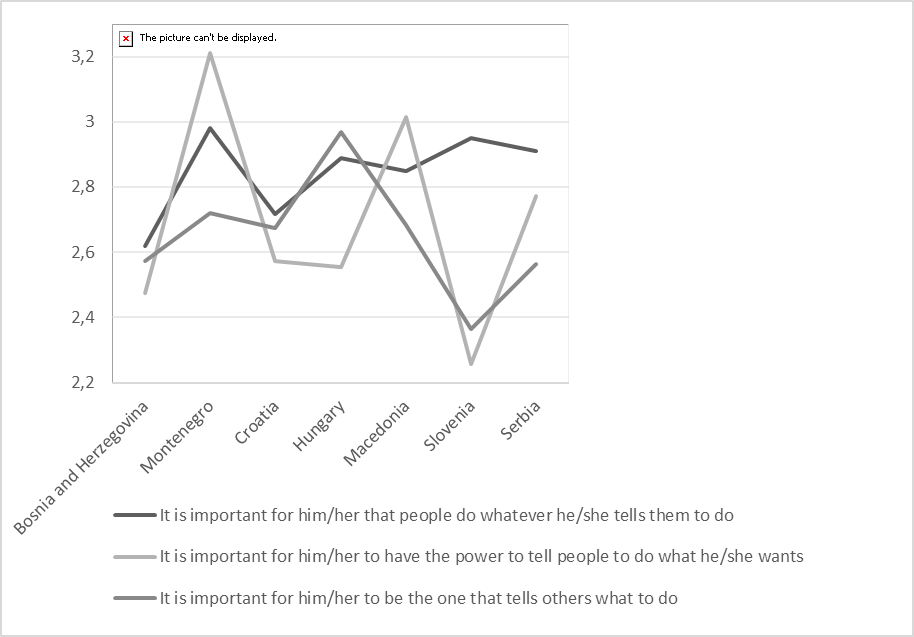

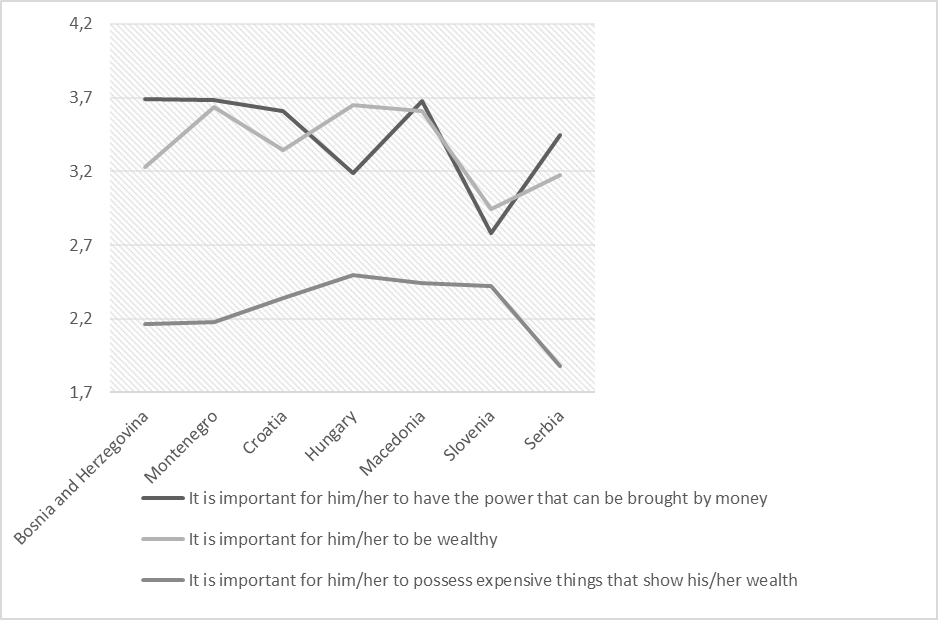

DESCRIPTIVE INDICATORS According to the descriptive analysis of rank, the results indicate that social values have a similar hierarchy with smaller discrepancies and differences (Table 2). In all states, power takes up the last position according to its significance, while other values take higher ranking positions. In accordance with the results shown in Figure 8 and based on the descriptive analysis, we can assume that the states of Southeast Europe have a mostly similar system of values. When we talk about the value of power (Figure 8 and Table 2), it can be observed that power takes up the last, tenth, position for all states in relation to other values. However, even though ranking positions are consistent for all states, there are differences in arithmetic means of the value of power, so power is the most important to participants from Montenegro and then consecutively to Macedonia, Hungary, Serbia, Slovenia and Croatia, while the lowest average of the value of power belongs to the participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Table 2. Whether the differences are statistically significant will be revealed by further results’ analysis. SIGNIFICANCE OF POWER OVER PEOPLE By observing individual tested statements, we can see that for power as value there are certain differences. So, for instance, in the linear combination making up the variable of the significance of power as domination over people, in Figure 9 – Significance of power as domination over people according to states, we can see statements seemingly measuring the same thing, the domination over people, although they can ultimately have different values. In this research, therefore, as in similar research related to social values, the average is taken i.e. a linear combination of all results and personal results of an individual and so a new variable is made. SIGNIFICANCE OF POWER OVER RESOURCES In Figure 10 we can see the trend of arithmetic means of the linear combination of the significance of power over resources. According to tested statements, we can see that each participant was asked about the extent to which the described person is similar to them regarding the importance of gaining and having wealth. Although being a seemingly personal value, on the macro level of a state it actually indicates to what extent it is important for a nation to have wealth i.e. natural and social resources[14].

SIGNIFICANCE OF POWER IN GENERAL

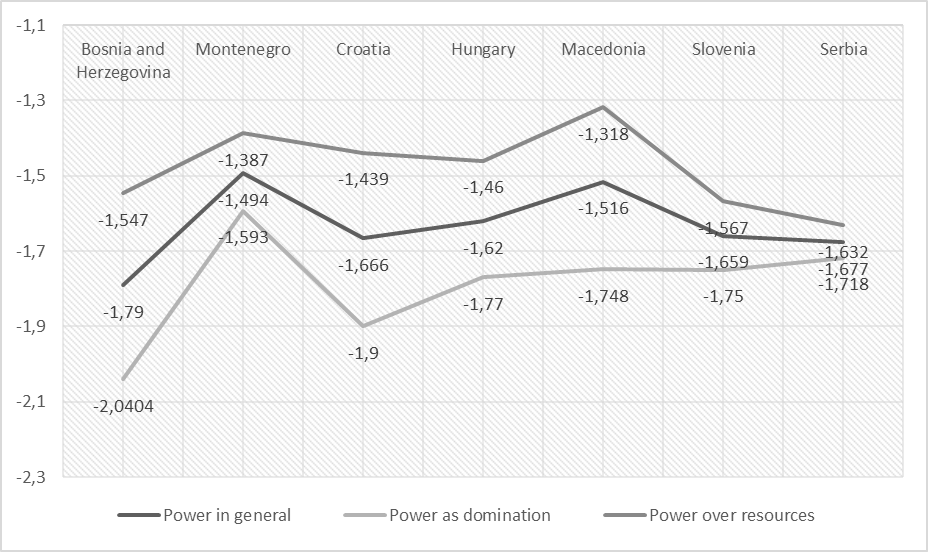

When we compare the arithmetic means per state for power in general, power as domination over people and power over resources, we can see that power over resources is more important than power of domination over people. Power in general represents the average, i.e. the linear combination of those two kinds of power as a value. MANOVA AND ANOVA After the descriptive indicators, we have tested statistically significant differences in power as value among the states.

| Effect | Pillai's Trace | F | df1 | df2 | Significance | Partial Eta Squared | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 0,031 | 2,308 | 18 | 3939 | 0,001 | 0,010* |

*significant at 5 % probability level According to the multivariate test, which determines the differences on multiple variables among multiple groups, there is a statistically significant difference among groups (significance equals 0,001). Further analyses will determine among which groups there is the difference and what it is like.

| Dental service | F | df1 | df2 | P | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power – domination | 5,101 | 6 | 1313 | < 0,001** | ||||||||||

| Power – resources | 0,793 | 6 | 1313 | 0,575 | ||||||||||

| Power in general | 2,466 | 6 | 1313 | 0,022* |

*significant at 5 % probability level According to Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance we can determine that the variance is not homogenous for the variables ‘power-domination’ and ‘power in general’, but it is homogenous for the variable ‘power-resources’. In accordance with that, there is a potential limitation because variances are not the same in all groups, in this case in all states. However, taking into consideration that MANOVA and ANOVA are very robust statistical procedures, the limitation is minimal.

*significant at 5 % probability level According to the results of ANOVA (Table 5), there is no statistically significant difference among groups considering the significance of power in general or the significance of power over resources. Nevertheless, there is a statistically significant difference for the significance of power as domination over people (p = 0,005). The results of the post hoc test (Table 6) show how the statistically significant difference in power as domination exists only between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, where for the participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina (M = –2,073; SD = 1,196) power as domination over people is statistically significantly less important than for the participants from Montenegro (M = –1,629; SD = 1,32). The post hoc test has not shown any statistically significant differences among other states in power as domination. We can therefore conclude that, considering all performed analyses, except

*significant at 5 % probability level. in the case of the difference between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro in the significance of power as domination over people, there are no statistically significant differences in the significance of power among the states of Southeast Europe. The aforesaid makes it apparent that in all the states, apart from the mentioned ones, power in general, power as domination and power over resources are equally significant, i.e. insignificant, taking into consideration that power takes the last ranking position in relation to other values in all researched states.

DISCUSSION

The results of the research have shown how power as a value in the states of Southeast Europe has been ranked in the lowest position, which adheres to the theoretical framework of values by S.H. Schwartz, according to which the value of power is also usually the least pronounced value in many observed general populations[14]. We have thus confirmed the H1 hypothesis. Furthermore, the results indicate how there is no statistically significant difference in the significance of the value power among states, except between Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which differ in the significance of the value power – domination over people, where it is less significant for the participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina to have power in the sense of domination over people than it is to the participants from Montenegro. Thus the hypothesis H2 has been partly confirmed. Taking into consideration that the participants in this research were students, i.e. young people, let us point out that the system of values is formed in childhood and adolescence and it is mostly formed and relatively stable in the age of young adulthood[17][25]. Therefore, the researching of the system of values in student population is of great importance because the trends in a continuous research of the system of value of young people are indicative of general trends in society[26]. So the results of the research with the population of young people point towards the future system of values of general population at the point when current participants enter their mature age. It is also important to say that the age of participants is a relevant predictor of the hierarchy of values, which changes through life under the influence of different occurrences such as war and crisis, physical aging, life status and similar. Younger participants in stabler and wealthier states will so exhibit more significance for the values of hedonism, stimulation, self-direction and universalism, and less on security, traditionalism and conformity. Aging positively correlates with security, tradition and conformity, and negatively with stimulation, hedonism and achievement[13]. The education of participants is also an important predictor of the hierarchy of values because it positively correlates with the years of formal education for the values of self-direction and stimulation, achievement and universalism and negatively for the values of conformity, tradition and security[13]. We have mentioned that sudden changes and discontinuity or discrepancies in the system of values of both young participants and general population indicate crisis situations in a person’s life and society, so that the system of values, which is, as already said, relatively stable in a person’s life, suddenly changes in the middle of an economic crisis, poverty, natural cataclysms or in the state of war[1]. This thesis is best illustrated by the results of two major studies conducted in the Republic of Croatia that tested the systems of values of the youth. In the study Position, awareness and behaviour of Croatia’s young generation from 1986, postmaterialist values were more prominent than in 1999 in the study System of values of the youth and social changes in Croatia[27]. The differences in the system of values of the youth determined in mentioned studies are explained as the consequence of war sufferings during the Homeland War and the economic crisis ensuing as the consequence of war devastations, but also privatisation and a huge loss of employment and mass emigration from Croatia. In fact, in accordance with Maslow[4], it is necessary firstly to satisfy existential needs (physiological and security needs as materialist values), while social needs (needs for respect and self-affirmation as postmaterialist values) are satisfied only after the existential ones have been satisfied. Therefore, the process that happened in the Croatian society is called the retraditionalization of values, because of the change from a prevailingly materialist and postmaterialist system of values into the system of prevailingly traditional and materialist values[17][28]. Let us also mention the findings of the study[26] according to which the deviant behaviour of the youth and their antisocial behaviour is positively correlated with a hedonistic orientation of values and negatively with conventional and self-actualizing dimensions of values so we consider that protective factors are the values of universalism, self-realization values and traditional values, while risk factors include hedonism, utilitarianism and power, which is the subject of this study. The aforesaid substantiates the relevance of choice of particularly student population as the sample of participants in this study because the understanding of the system of values of young people indirectly indicates possible predictors of socially inacceptable forms of behaviour of the young generation. Even though there is, for a more detailed discussion, a lack of results of similar cross-national research, which would produce comparative data comparable to the results of this study, it is nevertheless important to mention the results of the World Values Survey – WVS according to Inglehart’s concept and a specific measuring instrument. Based on the results of that study, the system of values in Croatia is placed into the 4th quadrant with the countries of Western Europe, and not with the countries of the former communist regime, because the study has shown that the participants simultaneously possess materialist values (traditional values and survival) and postmaterialist values (secular rational values and values of self-expression). The study was conducted for the first time in 1981 and in the Republic of Croatia it has been conducted by the scientific research team from the Catholic Faculty of Theology – University of Zagreb[29]. Up to now, five such studies have been conducted (in 1981, 1990, 1999, 2008 and 2017) and the data about the study itself and gained results can be found on the web site of the research project (http://www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu). Considering the value of power within ten motivational types, let us also point out that the results of this study have confirmed the findings of the major Schwartz’s cross-national research in which power takes the lowest 10th ranking position[8], i.e. that the participants from observed countries also marked the value of power as the least significant value. It is therefore interesting that a statistically significant difference in exhibiting significance for the value power is established only on the samples of participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. The reasons for such results have to be sought in the particularities and events from the recent past, the economic and social level of development of those countries, as well as their geopolitical position and other elements, which is not the subject of this study. Considering the results of previous studies, and in the context of finding the statistically significant difference, it is necessary to point out one more time that the value power is a risk factor for socially inacceptable forms of behaviour[26], so the result indicates the need to devise special prevention programmes, which would sensitize and educate the young population to recognize and prevent the occurrence of such forms of behaviour in those social environments where the value power is especially prominent. RESEARCH LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH The limitation of this research is a convenient sample that may not be representative and no conclusions can be drawn from the population as a whole. Furthermore, limitation is also an online survey that can affect the representativeness of the sample. Namely, in the recruitment of participants via Facebook, there was a voluntary completion of the questionnaire – therefore, at our request, the questionnaire was filled out by those who wanted through the link. There is a possibility that persons with a particular value system may be more inclined to complete the questionnaire, which may affect representativeness. There is a need to further explore this topic especially internationally and through the Internet to perfect measurement tools and online data collection methods.

CONCLUSION

Systematic researching of the system of values of various groups of participants and the general population of inhabitants is highly important for the understanding of general trends in society. Participating in longitudinal and cross-national studies of this type, like the World Values Survey – WVS or researching with Schwartz’s instruments for examining the hierarchy of the system of values, contributes to a better understanding of the modern context in which different societies do not coexist in minimal interaction, but they create new values in everyday communication and cooperation and, in spite of many challenges, they create the culture of peace and community. The fact that the value power gains the lowest results among ten motivational types of values clearly states that the modern world is not burdened by activities that would serve to achieve domination over other people or over natural or other resources. But, what applies to the general population, does not apply to every individual participant. Thus is the selected Schwartz’s questionnaire PVQ-RR a good choice for a measuring instrument, which simultaneously gives reliable information about the system of values of each individual[30]. The values of universalism, benevolence and self-direction are the most prominent values indicating the humanistic orientation of a man and the community he belongs to. The existence of those values in student populations in the states of Southeast Europe optimistically heralds the age of peace and security, alongside with a continuous analysis of risk elements of safety and other threats coming from different sources. We also come to the conclusion that the formation of the system of values is significantly influenced by general social processes within a society, which were explained by Ronald Inglehart in his modernization theory[15]. The limitations of this study are the inability to compare each of the observed student populations to the system of values of general populations in their home counties, as well as the fact that this study is conducted for the first time so the study results are not comparable in a chronological context. This study could, through multiple researching waves, provide clear answers on trends in the systems of value of student populations in observed countries of Southeast Europe, as well as the trends in systems of value in the geopolitical area in question.

REMARK

1The data for students are taken from state statistic offices, available for a specific state: Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina[31], Statistical Office of the Republic of Montenegro[32], Croatian Bureau of Statistics[33], Hungarian Central Statistical Office[34], State Statistical Office of Macedonia[35], Statistical Office of Slovenia[36] and Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia[37].