1. INTRODUCTION

The growth of Web 2.0 and social media has enabled the development of user-generated content (UGC) and created a new marketing era that refers to the "extended field of relationship marketing", which has shifted strongly towards the online environment and has reinforced the dynamic and interactive business environment in the hospitality and tourism sector (Kim, Yoo and Yang, 2019;So and Li, 2020). Tourism and hospitality service providers look for unique ways to involve customers in the value-added process and enable personalized experiences (So and Li, 2020). The authors López Barbosa, Sánchez-Alonso and Sicilia-Urban (2015) emphasized the enormous value of customers' feelings or attitudes towards services or products based on customer-generated content researchers, companies and customers themselves. In the age of experience economy, the perceived value of a product or service depends largely on the consumption experience and not on ready-made value propositions aimed at making customer experiences more inimitable and memorable (Lei et al., 2020). Brands in the tourism and hotel industry invest in digital marketing strategies (e.g. Facebook’s brand pages) to enhance customer engagement on social media (Su, Reynolds and Sun, 2015). The authors Kumar and Mirchandani (2012) stated that “these investments often see a substantial return on investment, as positive customer interactions in social media experience a ripple effect when they extend from a single user to the broader social network.” Therefore, customer engagement in social media can be seen as a crucial source of information, as previous studies show that customer engagement affects positively consumers’ brand awareness (Hutter et al., 2013;So et al., 2016), word-of-mouth activities (Hutter et al., 2013), improves customers' brand valuations and future purchase intentions (Hollebeek, Glynn and Brodie, 2014).

With the spread of UGC on various platforms, different opportunities have arisen for marketers and researchers. Through online sentiment analysis, the "big data" produced offered marketers the opportunity to gather marketing intelligence (Erevelles, Fukawa and Swayne, 2016) and researchers the ability to systematically extract and classify consumer sentiment about products and services expressed in comments and postings on social media sites in order to obtain brand attitudes and new market trends (Rambocas and Pacheco, 2018). User-generated content with a focus on comments/reviews in social media can significantly influence the buying decision of potential customers (Ma, Cheng and Hsiao, 2018). The authors Levy, Duan, and Boo (2013) pointed out that more than half of all hotel bookings are influenced by online reviews. Therefore, it is essential for business managers to stay current on technology, customers and social media to align marketing and business efforts with customer needs and issues (Moro and Rita, 2018).

The importance of continuous research on social presence can be seen in the previously highlighted survey on respondents' attitudes to Croatia's online reputation as a tourist destination (Mušanović, 2020). The results indicated that 72.8 per cent of the respondents use other tourists' comments as a source of information when searching for information online. A total of 49.8 per cent of respondents read consumer reviews on travel review portals, 46.2 per cent use social media as a source of information, 41.6 per cent use social sharing sites. The most reliable sources are those that offer up-to-date information (52.5 per cent) and those that have the most votes and likes (42.6 per cent).

Recently, in a literature review on the role of social media and advertising in hospitality, tourism and travel sectors, Chu, Deng and Cheng (2020) called for qualitative studies, as most studies relied on quantitative methods such as structural equation modelling, content analysis, descriptive analysis and regression analysis. Among others, only two studies with text analysis (Wattanacharoensil and Schuckert, 2015;Chang, Ku, & Chen, 2019) and six studies with thematic analysis were identified (Chan and Guillet, 2011;Lim, Chung and Weaver, 2012;Line and Runyan, 2012; (Blichfeldt and Smed, 2015;Blichfeldt and Smed, 2015;Moro & Rita, 2018). In order to contribute to the applied methods in social media and hospitality research, sentiment analysis is used.

Despite the above facts, the importance and significance of customer engagement and their feelings and/or attitudes towards services or products based on UGC cannot be ignored, given the fact that brand communication, advertising and customer engagement are the main business models for many social media platforms and should be researched continuously (Moro and Rita, 2018). The social networking platform Facebook is a good choice to maintain analysis as the largest social media platform that creates a dynamic environment for brand communication and consumer engagement (Su et al., 2015).

The purpose of the study is: a) to provide a general descriptive overview of comments posted by Facebook page followers; b) to identify specific textual attributes of hotel brand posts on social media that may lead to customer engagement (embodied here as reactions, comments, and shares); c) to apply the sentiment analysis to Facebook comments of four- and five-star hotel brands in Croatia; d) to identify and compare the feelings and attitudes of customers towards the staff, services and products that hotel brands promote by posting messages on Facebook pages; e) to offer meaningful implications for interactive marketing practitioners, online advisers, and social media website operators in the hospitality sector.

The aim of this study is therefore to answer the following research questions:

1. How active are the page followers (users) on the hotel brand's Facebook pages in terms of hotel categorisation?

2. Is there a difference between the sentiment scales of four- and five-star hotel brands in comments posted by page followers on Facebook?

3. What kind of sentiment do Croatian five-star hotel brands spread among Facebook users through comments posted on Facebook?

Following, the literature review, the research methodology is explained and the applied sentiment analysis data flowchart are described. Finally, the obtained results are presented and discussed and the most significant conclusions are reported.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Social media and advertising in tourism and hospitality

Only a decade ago, social media were considered to be platforms or applications that allow users to socialize, network and share digital content, information and/or sentiments (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). With the development of social media, such definitions no longer reflect the full potential and purpose of social media and it is agreed that social media have become one of the most important advertising venues for marketers Chu et al. (2020). Social media may serve today as a channel for a number of marketing activities, such as customer relationship management, customer service, buyer research etc. (Ashley and Tuten, 2014). In other words, as a “dynamic, interconnected, egalitarian and interactive organism”, social media has enabled brands and customers to connect through various platforms that allow social networks to build on common interests and values (Peters et al., 2013). This connectedness can be determined as strong or weak "social ties", which play an important role in determining the recommendation behaviour of customers (Verlegh et al., 2013;Li, Larimo and Leonidou, 2020).

Social interactions between brands and customers not only influence consumer decisions, but also the connection patterns of users and the strength of social ties indicate the intensity of social interactions (Aral and Walker, 2014;Li et al., 2020). The brand communication and generation of social media data has increasingly enabled brands to better manage customer relationships and improve business decisions (Libai et al., 2010). A large amount of social media data from different social media types and formats can be easily extracted and meaningfully used with modern information technologies, which helps tourism marketers to understand the actual sentiments and experiences of tourists.

The collection and value creation through social media data has been identified as a new strategic resource that can improve marketing results, it can also serve as an important source for customer analysis, market research and crowdsourcing of new ideas (Gnizy, 2019). It should be emphasized that social media platforms (primarily Facebook) are considered by advertisers as the most beneficial platforms for sharing brand-related content and promoting brand associations (Pütter, 2017).

The phenomenon of social media in hospitality and tourism has received a lot of attention from different perspectives. A content analysis study by Leung, Law, van Hoof, and Buhalis (2013) based on social media studies published between 2007 and 2011, showed that consumer-centred research focuses on the influence of social media on the travel planning process. Another content analysis by Nusair (2020) included 439 social media articles published in 51 hospitality and tourism journals between 2002 and 2016 and showed that social media research in hospitality and tourism is mainly based on quantitative methods. The author found that large datasets, netnography, Travel 2.0 and Web 2.0 were topics that marked a new trend in social media research that emerged between 2011 and 2016. The authors Chu et al. (2020) identified three main perspectives in literature, namely: use of social media from the consumer's perspective, organization’s perspective and the effects of social media, while Knoll (2016) identified seven main research topics on advertising in social media: use of advertising in social media, attitudes towards and exposure to advertising, targeting, user-generated content in advertising, electronic word-of-mouth in advertising, consumer-generated advertising and other advertising effects. The authors Leung, Bai and Erdem (2017) explored the message strategy and its effectiveness in a study of 1,837 messages from 12 hotel brand Facebook pages based on a quantitative methodology. The authors found that the picture message was the best message format. Leung (2019) proved that destinations' Facebook pages are effective in terms of improving fans' visit intentions. Leung (2019) conducted an extensive literature review of Facebook marketing research in the tourism and hospitality industry with three objectives. The first was to investigate how Facebook influences fan behaviour through survey methods and modelling (Choi, Fowler, Goh, and Yuan, 2016;Kang, Tang and Fiore, 2014;Lee, Xiong and Hu, 2012;Leung and Tanford, 2016). Second, to develop a typology of Facebook messages based on content analysis and examine the attractiveness of messages based on the number of likes, comments and shares (Kwok and Yu, 2013;Wang and Kubickova, 2017; Su et al., 2013;Leung, Bai and Erdem, 2017). The third purpose of Facebook marketing research is to investigate the marketing effectiveness of messages through experimental design (Atwood and Morosan, 2015;Cervellon and Galipienzo, 2015;Ladhari and Michaud, 2015;Leung, Tanford and Jiang, 2017). The monetary value of a single Facebook “like” to a business in general is found to be considerable (Gruss, Kim and Abrahams, 2020).

More recently, researchers have shown a growing interest in exploring what encourages likes, comments and shares (Mochon, Johnson, Schwartz and Ariely, 2017), while marketers are replacing advertising-based content with brand-based content in an effort to increase social media activity and customer engagement (Facebook for Business, 2013).

2.2 Branding with social media

Branding has been identified as a topic of great relevance to attract consumer attention and to respond with messages to promote brand building and stimulate purchasing behaviour in the hotel industry worldwide (Forgacs, 2003;Moro and Rita, 2018). Brand communication on social media refers to any brand-related communication “distributed via social media that enables internet users to access, share, engage with, add to, and co-create” (Alhabash, Mundel and Hussain, 2017). Brand presence on social media occurs as paid display advertising, brand participating in social networks as a brand persona, published branded content, and branded engagement opportunities for consumer participation (Ashley and Tuten, 2014). Therefore, the social media business model perspective plays an important role as companies generate revenue while offering free services and users make their final purchasing decisions. As a result of brand activities in social media, brand awareness and brand liking can be increased, customer loyalty and engagement can be promoted, the mouth-to-mouth communication of consumers about the brand can be stimulated, and traffic can be directed to brand locations online and offline (Ashley and Tuten, 2014).

Alalwan, Rana, Dwivedi and Algharabat (2017) conducted a literature review on social media in marketing and examined 35 articles with related topics on branding through social media platforms, arguing the crucial influence of marketing activities on brand awareness and identity. Muk and Chung (2014) proved that customers can be motivated to follow a brand site in social media by hedonic and utilitarian factors. Christo (2015) empirically investigated that the characteristics of social media brands play a strong role in predicting customer trust, with a consequence of a positive impact on brand loyalty. Furthermore, Smith and Gallicano (2015) confirmed that Twitter and Facebook are more effective social media platforms for communicating with customers and creating and presenting brand stories than YouTube. Nusair, Bilgihan, Okumus and Cobanoglu (2013) assured that brand innovation is influenced by the importance of social media as a strategic mechanism.

Brand presence and advertising messages in social media must be carefully designed to serve their purposes. Since travel experiences are intangible, advertising focuses essentially on images and can evoke and influence the message recipient’s mental imagery of the hotel or trip (Wang and Lehto, 2020).

2.3 Sentiment analysis in the hospitality context

The development of sentiment analysis was driven by the need to know what others think (Ma et al., 2018). Thanks to the advances in machine learning and data mining, sentiment analysis techniques provide an opportunity to transform qualitative data into quantitative emotional values in a series of words or texts, to compare their online presence with that of their competitors and to create possibilities for more innovative research design (Ma, Cheng and Hsiao, 2018). Therefore, the goal of automatic sentiment recognition is to provide information and extract sentiments from behavioural data. Opinions and attitudes are essential components of interactions between parties, as they provide information that helps to interpret the meaning behind a person's behaviour (intentions) (Zhang and Provost, 2018).

Although the sentimental analysis has been examined in different areas, this paper focuses on the field of social media in hospitality, which is a relatively new phenomenon that started approximately ten years ago with the authors Pekar and Ou (2008). The authors performed sentiment analysis (Termextractor22 tool was used) on 268 customers’ hotel reviews based on the natural language processing algorithm with expressions describing different hotel features. The main outcome of this study was the developement of the sentiment relationship between the topic of the sentence and the sentiment itself. Shi and Li (2011) performed the sentiment analysis on a sample of 4000 positive and negative hotel reviews using the support vector machine (SVM) based supervised machine learning model. To improve the understanding of visualizations, Chen, Chen and Takama (2016) applied latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) to cluster reviews. An interactive visualization system was proposed by the authors, it presented sentiment words with aspects based on natural language processing and sentiment lexicons. Geetha, Singha and Sinha (2017) explored the relationship between customer sentiment and online customer ratings of 496 hotels. The authors used the supervised learning algorithm and performed the analysis using Wordnet 3.0 abs Sentiwordnet 3.0 tools. The customer ratings and actual customer feelings were shown to be consistent across hotels belonging to the two categories of premium and budget. The findings of Park, Kang, Choi and Han (2020) show that the feedback reviews of re-visitors tend to contain more words in a sentence and reveal more positive/negative sentiments than those of one-time visitors. The authors used linguistic inquiry and word count to conduct a sentiment analysis on the user feedback reviews. Luo, Hunag and Wang (2020) applied a sentiment analysis on 363,723 Chinese-text online reviews using the Jieba tool for Python and the Word2Vec tool to calculate similarity and term frequency. The most positive sentiments are associated, by location followed by facilities, service, price, image and reservation experience, while negative sentiments include sound insulation, air conditioning, bedding, windows, toilets, TV sets, WiFi signals, towels, elevators, hair dryers, slippers, toilet bowls, cash return, bills. The authors Ma et al. (2018) gave a critical overview of the origin, development and process of sentiment analysis in the context of hospitality research and emphasized the beginning of the use of sentiment analysis to analyse customer comments, although hospitality organizations rely heavily on word-of-mouth on the Internet.

The text analysis has provided a set of tools for the direct analysis of text content in social media, especially in the area of novel feature sets, sentiment analysis and semantic understanding (Gruss, Kim and Abrahams, 2020).

3. METHODOLOGY

Before the coronavirus COVID-19 triggered an unprecedented global crisis with enormous impact on the political, social and economic system, Croatian tourism was in its "full bloom", breaking tourist records year after year. In 2019, Croatia recorded 21 million tourist arrivals and 108.6 million overnight stays, as published by the Ministry of Tourism and Sport of the Republic of Croatia (2020a). For the first time in Croatian tourism history, more than 20 million tourists visited the destination (90% was accounted by foreign tourists). In total, 39 million overnight stays were recorded in private accommodation, 25 million overnight stays in hotels and 19 million overnight stays at campsites (Ministry of Tourism and Sport of the Republic of Croatia, 2020a). Therefore, it is considered appropriate to conduct the analysis on Croatian hotel brands on social media.

According to the official data published by the Ministry of Tourism of the Republic of Croatia in January 2020, a total of 44 five-star hotels and 329 four-star hotels are categorized (Ministry of Tourism and Sport of the Republic of Croatia, 2020b). The data was collected in February 2020 using NCapture for NVivo and manually from Facebook, as the most popular social networking site. Given the large number of hotel brands in Croatia, several selection criteria had to be defined. First of all, in order to narrow down and specify the sample, hotel brands listed on the first ten pages of the website www.booking.com sorted by hotel rating and category were included in the sample. Secondly, all selected hotel brands had to be searched and checked for an official Facebook website. Hotel brands that did not have an official hotel brand Facebook page, hotel brands that did not post in English and hotel brands that did not post at least three postings per month were excluded from the research. Finally, the sample comprised a total of 31 hotel brands, namely 10 five-star hotel brands and 15 four-star hotel brands. Thirtheen 4-star hotels are located at the searside, of which four belog to hotel chains. Two 4-star hotels are located in the continental part of Croatia. Eight 5-star hotels are located at the seaside, of which six belong to hotel chains. Two 5-star hotels are located in the contentnal part of Croatia of which one belongs to the hotel chain. One, two and three-star hotel brands were not observably active on their Facebook pages and were therefore excluded from the sample. The analysis included postings and comments from hotel brands published from January to December 2019. A total of 1,743 comments and 1,026 postings from 5-star hotel brands, and 2,505 comments and 1,347 postings from 4-star hotel brands were collected.

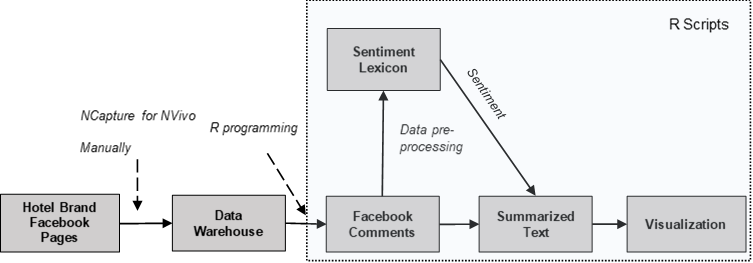

Before data analysis, common text pre-processing functions from R's tm package in R Studio were applied. These functions are: tolower (makes all text lower case), removePunctuation (removes functions such as dots and exclamation marks), stripWhitespace (removes tables, extra spaces), removeNumbers (removes numbers), removeWords (removes certain words (e.g. he and she) or data scientist defined step words), stemDocument (reduces prefixes and suffixes on words, making term aggregation easier). To obtain meaningful results, additional functions were applied to remove hypertext transfer protocols ("http"), World Wide Web ("WWW") and symbols such as hashtags ("#") and at signs ("@"), as some comments only contained tags from relatives or links to web pages. The flow chart of the proposed system for mining Facebook comments towards hotel brands is illustrated inFigure 1. Furthermore, the analysis only contained comments in English, German and Italian. Finally, a sample of 725 postings from 5-star hotel brands and 705 postings from 4-star hotels was included in the final analysis.

To answer the research questions, sentiment analysis with the AFINN and Bing lexicons was applied. The non-binary AFINN lexicon manually rates words from -5 to 5, with negative values indicating negative sentiment and positive values indicating positive sentiments. The higher the score, the higher the degree of positivity or negativity. There is no fixed range within which AFINN ratings are limited. The Bing lexicon categorizes words in a binary fashion into positive and negative categories.

The sentiment analysis aimed to obtain a calculation of emotional polarity (positive and negative) and an understanding of the attitudes, opinions and emotions expressed. A major advantage of sentiment analysis is that online comments can be collected and analysed in real time. Despite the challenges of automatically detecting sentiment in text (e.g. complexity and subtlety of language use, use of creative and non-standard language, lack of para-linguistic information, lack of large amounts of labelled data, subjective and cross-cultural differences) (Kwartler, 2017), the authors proved the accuracy of given sentiments and results.

4. RESULTS

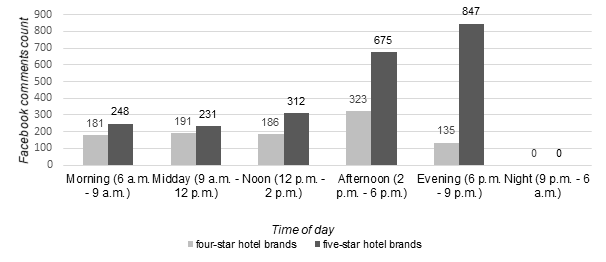

To gain insight into the characteristics of comments published in hotel brand posts, a descriptive outline is provided. According to the analysis, in 2019 a total of 1,026 postings and 1,743 comments from Croatian five-star hotel brands and a total of 1,347 postings and 2,505 comments from Croatian four-star hotel brands were recorded on Facebook pages. Of the 88,126 page followers of four-star hotel brands on Facebook, most are active during the day and in the afternoon. In total, 881 comments are posted during the day, 135 in the evening and none at night. Of the 244,790 page followers of five-star hotel brands on Facebook, most comments are posted in the afternoon (675) and evening (847).

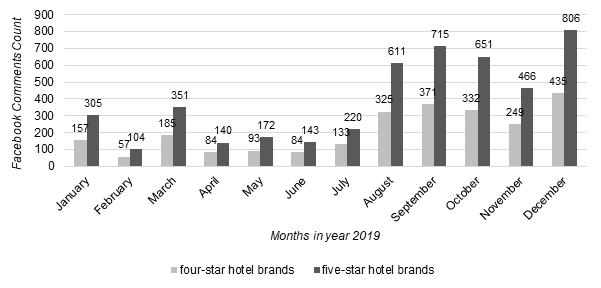

The descriptive analysis of both hotel brand categorizations shows that the activity of Facebook followers is highest from August to December, reflecting the end of the peak season and the low season. The lowest activity is seen from January to July (Graph 2).

To identify specific text attributes of hotel brand posts in social media that lead to customer engagement, customer reactions (emojis), comments, shares and number of page followers are collected to calculate the index of interaction rate. The interaction rate index indicates the number of interactions (reactions, comments, shares) in relation to the size of the page (Lies and Fuß, 2019). According to the four-star hotel brands, a total of 204,814 customer reactions (emojis), 2,505 customer comments, 6,039 customer shares and 244,790 page followers were observed. The interaction rate is 87.16 and indicates the average number of interactions per 100 followers of the site, which is very low and is not considered successful.

According to the five-star hotel brands, a total of 144,947 customer reactions (emojis), 1,743 customer comments, 3,321 customer shares and 88,126 page followers were observed. According to this, the interaction rate is 170.22 and indicates the average number of interactions per 100 followers of the site, which is slightly higher but still relatively low.

In previous research, researchers found that social media turned users from passive to active consumers who create content about products and consumption experiences (Bigne et al., 2020). In this case, the page followers of four- and five-star hotel brands in Croatia behave like passive users (lurkers) and tend to read posts and comments, view posted photos or videos and have little engagement with the hotel brand and other page followers.

When looking at the frequency analysis of extended positive words, the word beautiful is most frequently mentioned in Facebook comments from four- and five-star hotel brands (35 and 49, respectively). The analysis also showed that Facebook page followers in both hotel categories use almost the same positive words in their comments. Facebook comments of four-star hotel brands contained the word great 35 times, nice 30, best 19, love 26, well 10, happy 16 times. Facebook comments of five-star hotel brand contained the word great 20 times, nice 10, best 41, love 31, well 15 and happy 21 times. Other words most often used in comments are glad, top, awesome, good, amazing, perfect, enjoyed, right, wonderful, fabulous, kindly, stunning, super, top, luxury, thankful, warm, work, recommendation, incredible, joyful, lucky, helped and few more.

The frequency analysis also showed that the comments of four-star hotel brands contained more negative words than the comments of five-star hotel brands. The most common negative words in comments on four-star hotel brands are bloody (2), cold (2), hell (2), limited (1), bad (1), bug (1), jealous (1), sad (1), problem (1), worry (1), while the most negative word in the comments on the five-star hotel brands was hard (2), bad (1), blur (1), cheating (1), complaining (1), jealous (1), incomparable (1), nervous (1), sad (1), shame (1), ugh (1).

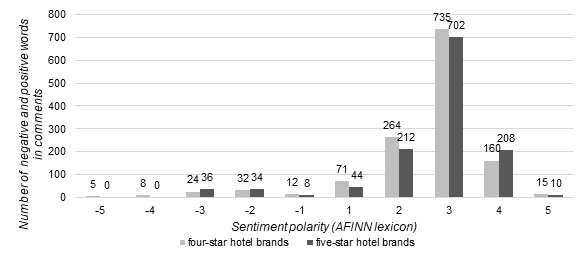

In order to fulfil the aim of this study, the sentiment analysis was carried out (Graph 3).

Source: Authors

The analysis showed that the observed Facebook comments contain predominantly positive sentiments. Specifically, four-star hotel brand postings contained a total of 81 negative words and 1,245 positive words. Only 5 words had a sentiment value of -5, 8 words had a sentiment value of -4, while the most negative sentiment values receiving a value of -2. In contrast, 735 words received a sentiment value of 3, followed by sentiment value 2 with 264 words, sentiment value 4 with 160 words and the lowest sentiment value 5 with 15 words.

The analysis of the automatic classification of the sentiment polarity of five-star hotel brands shows that the comments with the values -5 and -4 did not contain negative sentiments. Almost the same number of words contained the sentiment values -3 and -2 (36 and 34 respectively). The distribution of the words with positive values is amounts as for the 4-star hotel brands. The sentiment values contained the most positive words (702), followed by sentiment value 2 (212 words), sentiment value 4 (208 words), sentiment value 1 with 44 words and sentiment value 5 with 10 words.

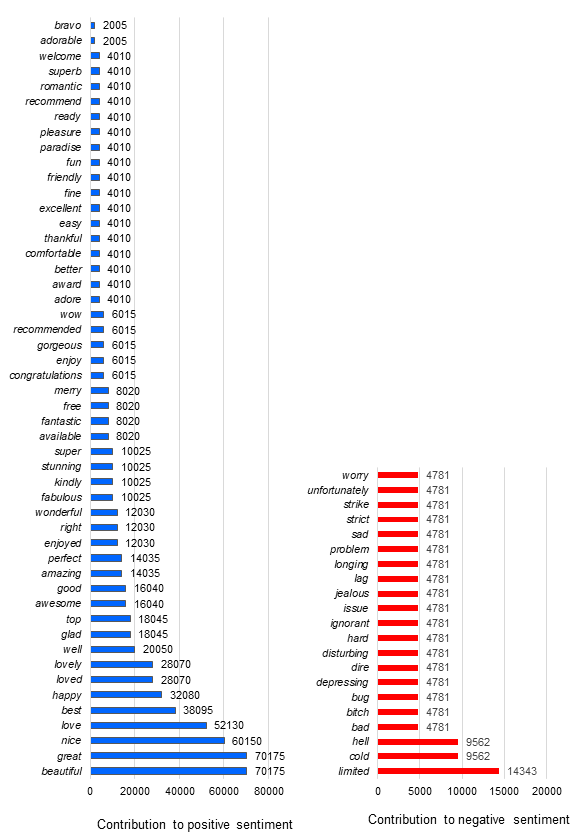

In addition, the authors draw word contributions on the sentiments of the comments in four-star hotel brands using the Bing lexicon inGraph 4. The Bing lexicon has created data on the contribution to sentiment and clustered them into "positive" and "negative" sentiments.

Source: Authors

As shown in the analysis of 4-star hotels, the words beautiful and great are the most commonly used words, which contributed to the positive sentiment with frequencies of more than 70,000. The smallest contribution to positive sentiment refers to the words bravo and adorable with frequencies of 2,005, and the words welcome, superb, romantic, recommend etc. with frequescies of 4,010. The words limited, cold and hell are words that mostly contributed to the negative sentiment with frequencies of 14,343 and 9,562 respectively.

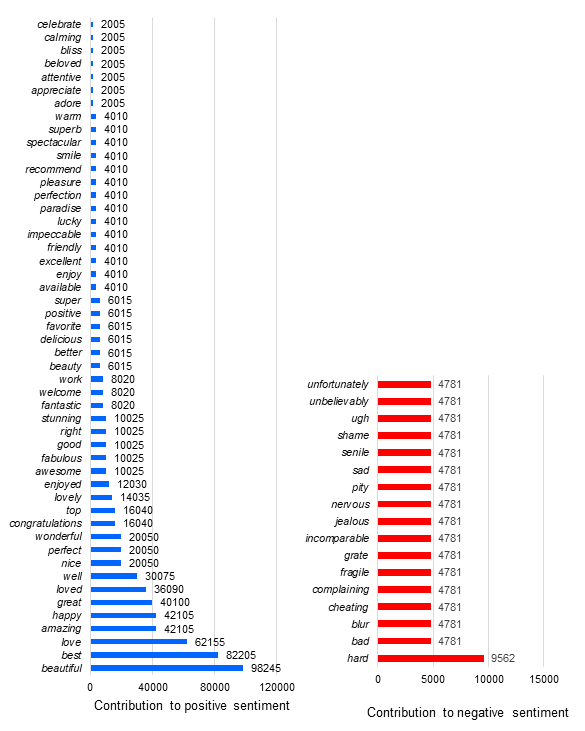

Source: Authors

When analysing the contribution to sentiments of five-star hotel brands, the highest contribution to positive sentiment was identified by the words beautiful with a frequency of 98,245, best with a frequency of 82,205 and love with a frequency of 62,155. The lowest frequency of contribution to positive sentiment is identified by the words celebrate, calming, bliss, beloved, attentive, appreciate and adore with frequencies of 2,005.

The highest contribution to negative sentiment refers to the words hard (9,562), while the contribution of 4,781 refers to the other negative words such as bad, blur, cheating, complaining, nervous, pity and sad (seeGraph 5).

To ensure that the words accurately reflect the sentiments, the validation was achieved by analysing the Facebook comments of the hotel brands by sentiment polarity:

• Positive sentiments

[1] Our most favourite hotel by far... adore Dubrovnik hotel, adore Zagreb... what’s not to love about beautiful Croatia...

[2] A beautiful hotel with super friendly staff who gave us a great welcome and looked after us very well on our stay. This hotel has got it so right! Hope to return soon!

[3] Great hotel great staff great everything ❤️

[4] Stayed there in June 2019... loved my stay #needtocomeback

[5] Love staying here, best hotel in Zagreb and close to everything you need ❤️

[6] Simply the best!!!

[7] It’s a gorgeous pool with lovely views across the bay to the old Venetian town of Trogir.☀️

[8] Absolutely beautiful place enjoyed it so much

[9] Ah, a great location for a perfect summer vacation. See you. :) And merry Christmas to you too!

[10] Yes, now it is the second time and its fantastic.

• Negative sentiments

[1] Is the contest limited to only 1 photo/participant? I can´t find this in terms&conditions

[2] Bloody hell time goes fast

[3] And to dam cold to actually get in the water

[4] Ashleigh M. depressing!!!!!

[5] Sexistic adv made by ignorant marketers. NOT your style. Think deeper

[6] I stayed at the hotel a few years ago. There's a parking problem

[7] It's always hard to leave

[8] Such a beautiful place. But a real shame you don't allow non-residents to experience the beauty or sit outside your lovely bar area with a coffee of a morning or a drink of an evening

[9] What a pity there's no floating class this week! We would have loved to try it!

[10] Oh, you SO deserve this treat! So happy for you. I’m in recovery... trying to get doc to sign-off paperwork so I can leave the hospital! Ugh...

5. CONCLUSION

Brand communication on social networks has a significant impact on customers' emotional reactions. Nowadays, it is common for customers to publicly express their thoughts and feelings on social media platforms. Therefore, it is essential for companies, especially hotels, to efficiently analyse customers' opinions and use them to design their future communication strategies.The purpose of the study was to provide a general descriptive overview of comments posted by Facebook page followers to identify specific textual attributes of hotel brand posts on social network site and to apply the sentiment analysis to identify and compare the feelings and attitudes of customers towards the staff, services and products that hotel brands promote by posting messages on Facebook pages. New insights were gained by reviewing the activity of hotel brand followers and the sentiment of hotel brand comments on Facebook. The advantage of applied sentiment analysis can be reflected in the fact that it enables researchers and practitioners to exponentially update user-generated content on social media platforms.

This research included an integrated framework to collect, preprocess data, extract sentiment teatures from Facebook posts, classify information and visualize the sentiment results. The results of the sentiment analysis indicated that the sentiment was more positive than negative, which is not surprising, as hotel brands strive to present themselves as positively as possible to draw customers' attention to booking and returning to their hotels. Comparing the contents of both hotel categories in terms of Facebook comments, it can be concluded that there was no significant difference in content and sentiments. The extracted positive words refer to location, service, facilities, image, reservation, circumstances, staff, etc. The negative words mostly refer to individual cases related to the experience of the service and the tourist offer. Apart from the fact that every hotel brand tries to achieve guest satisfaction with its services and offers, in this case only a small number of comments are identified with negative sentiments. Furthermore, the analysis reveald that the four- and five-star hotel brand Facebook pages differ slightly from the activity perspective in terms of the number of likes, comments, and shares. It is interesting to note that the majority of analysed followers of Croatian hotel brand pages are lurkers (passive users) who view posted content and read comments on posts, but rarely or never actively interact (respond, comment or share). This raises the question of whether hotel Facebook content managers are using appropriate brand communication strategies. Research by Kusumasondjaja (2018) found that social media users are more likely to respond positively when the message is created in a conversational or interactive approach, while they avoid interacting with brand content created in a self-oriented style.

The results offer meaningful implications for interactive marketing practitioners and hotel management in general, online consultants, social media site operators and academics. The literature review in this study established the relevance of the given topic and contributed to the state-of-the-art of qualitative research in the field of tourism and hospitality in social media. From a practical point of view, the analysis of large amounts of data and involvement in social media are becoming increasingly relevant to consumer behaviour, customer engagement, changes in brand awareness and the growth of electronic word of mouth (eWOM), but also have a significant impact on the attitudes of newcomers to the business. It appears that practitioners in online media and in the tourism and hotel industry play a crucial role in encouraging and facilitating customer engagement. This study can help managers look beyond hotel ratings to the sentiments customers have about hotels on social media sites. Human language can express emotions that qualitative ratings cannot capture. Hotel brands and marketers should focus on increasing the number of their Facebook followers, paying attention to the social influence of Facebook pages, converting passive users into active users to increase interaction rates and brand awareness, and responding to both positive and negative online comments to improve and maintain their image and respond to customer needs. In addition, hotel managers and marketers should hire staff trained in the use of open source software and programming languages such as R so that they can develop algorithms that best suit their needs and allow them to make the most of valuable, freely available and up-to-date data. The application of sentiment analysis can suitably provide operational and strategic improvements. The real guest experience data provides a more general and truthful interpretation than perceived data from a survey. In addition, the daily application of visual and multimedia analytics could provide an essential tool for risk control and promotion. This indicated that the crucial role of the service provider in creating an environment in which interaction and exchange can take place successfully (Grönroos, 2008). It should be emphasized that no similar studies have been identified that directly contribute to Croatian hotel industry and serve as a basis for further analysis in this area.

This study has several limitations. The results cannot be generalised, as only a total of 25 four- and five-star hotel brands were included in the study. The current study takes into account only one social media platform and comments written in English, German and Italian. The comments of several platforms should be analysed and compared with different algorithms and lexicons supporting several critical languages such as Croatian. Therefore, further studies should address these limitations in order to expand the results. The application of sentiment analysis faces several challenges mentioned in this study. Sometimes users express their opinions in a sarcastic way that is difficult to detect. Despite these limitations, this study provided meaningful results by applying a powerful tool for understanding consumer sentiments.