1. Historical development of the pension system

The system of generational solidarity is attributed to the German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, who delivered a speech in 1881 in the Reichstag advocating that people who are too old to work or who cannot work and generate income be afforded a dignified life (Stein, 1897? ). The term "peculium", which represents the amount of money that was allowed in the ancient Rome for slaves to dispose of and save for the purpose of redeeming liberty towards the end of his working life, which Bismarck then used in his speech, is at the root of the word "pension" which has grown worldwide (Sinn, 2004). The Bismarck bill was passed by the German Parliament in 1889 and subsequently adopted by numerous other states (Herbay, 2014). However, due to the changed circumstances today, this system is facing new challenges. Countries with the Bismarck system spend on average about ten percent of their gross domestic product on pensions (Conde-Ruiz and Gonzalez, 2016).

The first forms of pension funds and paid pensions in Croatia appeared in the mid-nineteenth century and were related to particular occupations, such as government officials and servants, and soldiers and their families. At the end of the nineteenth century, the beginnings of German pension insurance reached Croatia through Austria-Hungary, which is still being applied today in a somewhat changed form. Mining fraternities and mutual assistance organizations were established throughout Croatia, followed by the establishment of similar associations of workers in the construction and railways (Puljiz, 2007). Due to the outbreak of World War I and subsequently to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the pension system at the time failed to materialize, and workers' mutual assistance organizations went bankrupt. In 1922, a law was enacted to provide for uniform compulsory insurance of workers against the risks of old age, disability and death. In the same year, the Central Office for the Insurance of Workers, or the ancestor of today's Croatian Pension Insurance Institute, was established in Zagreb. The general workers 'pension scheme did not apply until 1937 because of adverse economic and political circumstances and because the social partners at the time could not reach an agreement on its financing, but the Central Office for Workers' Insurance still paid pensions to certain categories of insured persons, those taken over the succession of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and those who have acquired a pension due to an accident at work or an occupational disease. Pension insurance was funded by contributions of three percent on wages and was paid by employers and workers. The retirement age was 70 years, like the one in German law of 1889, so that workers' pensions were hard to come by even if the functioning of the system was not hampered by the political and economic difficulties of the time. It is interesting that today's Croatian Pension Insurance Institute changed its name several times, but it is still housed in the same building that the then established Central Office for Insurance of Workers had built. After the end of World War II, the Central Institute for Social Security was established, and pension insurance based on generational solidarity was part of a single social security system. In the first period after the end of the war, the pension scheme was restricted to workers, war participants and war victims, while craftsmen and individual farmers remained outside the pension system. They were introduced into the system in the late 1960s and early 1980s, and their pensions were much lower than workers' pensions (Puljiz, 2008). From today's perspective, it seems almost unbelievable that in 1946 only 10,104 people received pensions (Brkašić et al, 2002). In 1971, there was a separation of pension from health insurance. In the years that followed, a number of international social security contracts were concluded covering Croatian workers abroad, and direct relations were established with German and Austrian pension providers, where about 80% of Croatian emigrants worked.

2. The effectiveness of the reforms implemented

After the independence of the Republic of Croatia, national pension and disability insurance funds for workers, sole proprietors and individual farmers were established. The transitional and economic crisis of the early 1990s and the war greatly hindered the transformation and functioning of the pension system in the early years of independence. With significant evasion of contributions, the number of new pensioners increased sharply at that time, with the simultaneous decline in the number of insured persons, ie those who had to finance the system based on intergenerational solidarity, so that the pension system found itself in a financially difficult situation that required its reforms. The first reform came into force in 1999, most importantly raising the retirement age, extending the pension calculation period, changing the indexation method and a new way of calculating pensions using points, and tightening the criteria for obtaining disability pensions (Vukorepa, 2015). The measures were aimed at mitigating or stopping negative trends and stabilizing the situation and developments in the pension system. The emphasis of the 1999 reform was on financial sustainability rather than on expenditure cuts because once acquired pension rights are permanently guaranteed and cannot be reduced (Marušić, 2003). Although the measures temporarily improved the financial sustainability of the system in terms of reduced inflows of new retirees and lower growth in pension expenditures, they led to a significant difference in the amount of pensions acquired before and after the reform came into force. This disruption was corrected during 2007 and 2008, raising pension expenditures again, but with the difference that this increase is paid from the state budget.

In 2002, under the influence of the World Bank, a new pension reform began (Stubbs and Zrinščak, 2009). This reform, based on three pillars, aimed at diversifying pension sources, increasing individual accountability for pensions and contributing to the long-term financial sustainability of the system (Puljiz, 2011). However, it should be noted that during the 2008 global recession, due to the fall in securities prices on the global financial markets, the viability of pension pain funds was called into question, which indicated that such a pension system had weaknesses (Olgić Draženović et al, 2018). In 2010, a gradual leveling of the conditions of age for women and men was adopted, an attempt was made to reward persons who became eligible for full retirement age and remain in the world of work, and discontinued early retirement. The aforementioned discouragement of early retirement through smaller pensions was not a penalization, but had a mathematical and economic justification, since such pensioners pay shorter and thus pay less for the system, while on the other hand they draw pension relatively longer (Vukorepa, 2011).

Today's pension system in Croatia, at least in formal terms, is a combination of a system of generational solidarity and capitalized savings. In addition to the security component, individual capitalized savings brings a component of equity to the pension insurance, since the insured person receives a pension that is in line with his / her previously paid contributions (Dujmović, 2011). It is a personal, individual savings of each policyholder that is capitalized which means that it is increased by a certain yield. Although funds from the insured are collected and managed by pension funds, which are divided into three risk groups according to investment strategies, the payment of pensions is made exclusively through mandatory pension companies. The first, main pension pillar is the system of generational solidarity, and it pays three quarters of the pension contributions, or 15 percent. The second pillar is a compulsory pension pillar of capitalized individual pension savings, in which 5 percent, or one quarter of pension contributions, is paid, while the third pillar represents additional, voluntary pension savings. However, there were also problems with the different pension levels of persons born between 1952 and 1961 who were able to choose whether to enter the second pillar or remain only in the first and persons born after 1961 who were by law had to enter the second pillar. Namely, the total pension to be paid from both pillars is lower than that paid only from the first pillar due to insufficient accumulation of funds in the second pillar. There were two reasons for this: a short pay period and insufficient growth in second-pillar allocations, as was intended at the time of the adoption of the 2002 pension reform. Allocations for the second pillar have gradually increased to 10 percent, but so far have remained at the initially adopted 5 percent. This has led to the calculation of pensions for persons in both pension pillars being less favorable than for persons in the first pillar only. The most recent pension reform, the one from 2019, stipulates that future retirees receive a statutory allowance of 27 percent for a portion of the pension relating to second-tier funds if they are transferred from the second tier to the first tier or an allowance of 20.25 percent for pensions from the second pillar if the insured person does not wish to transfer these funds to the first pillar. The same reform penalized early retirement and wanted to raise the retirement age to 67. These changes sought to equalize the amount of pensions on the one hand, and to some extent relieve the pension system in the longer term, but due to public pressure, the shift in the age limit has been halted for the time being.

3. Financial characteristics of the pension system of the Republic of Croatia

When Europe's first pension systems were in place, the retirement age was generally between 65 and 70 years. Due to the circumstances at the time and the average life expectancy at the time, this limit was such that few people even reached retirement, and if so, retirement generally did not last long. However, after the end of World War II, there is a significant reduction in the retirement age. A little later, due to the high unemployment occurring in Europe in the 1980s and 1990s, the practice of early retirement expanded into the life of the insurer in the 1950s. So, too, the institution of early retirement took root in Croatia, and in the mid-1990s, the average insured's retirement age was only 54 (Puljiz, 2005). In European countries, it was believed that this would solve the unemployment problem, that is, it would create more jobs for young unemployed people and that it would stimulate growth. By forcibly passivising one part of the working population contingent, the opposite was generally achieved: employers used early retirement to reduce labor and rationalize costs, and a large number of new retirees significantly increased the pressure on already overburdened pension funds. In Croatia, too, the pension system has been widely used as a means of alleviating social problems and rising unemployment. Within the pension system, economic problems that, by their very nature, belonged more to other social subsystems, such as social welfare in the narrow sense or the unemployment program, were often addressed at high and long-term costs (Marušić, 2003).

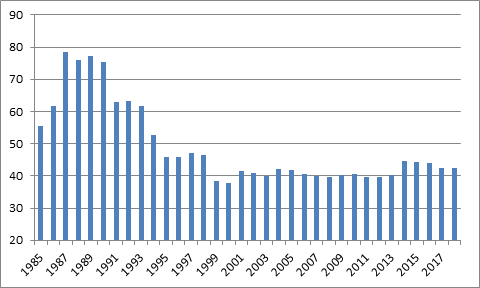

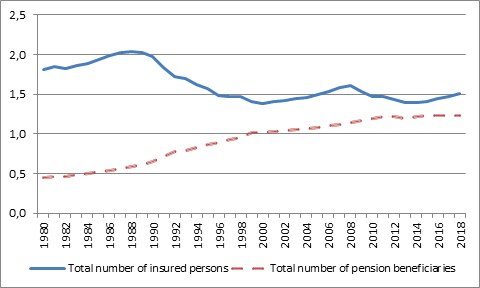

After 2000, a large decline in the number of insured persons was stopped, and since then their number has stagnated and ranges from 1.4 to 1.6 million, but on the other hand, the number of pensioners is increasing.Chart 1 shows trends in the number of insured persons and the number of pension beneficiaries.

Source: HZMO (2019)

A look at the trends in the number of insured persons and the number of pension beneficiaries indicates the financial unsustainability of the pension system under the current conditions. The curve of the number of pension beneficiaries is steadily increasing, reaching 1.2 million at the end of 2018, while the curve of the number of insured persons, after a noticeable major decline in the early and mid-1990s, is stagnant and is about 1.5 million. The movement of the curves indicates that they may intersect in the near future, that is, there may soon be more pension beneficiaries than insured persons. It is a process that may be slowing down, but it is unlikely that trends can change and that process can be avoided. The difference in the number of insured persons and pension beneficiaries decreased from more than 1.3 million in 1990 to less than 0.3 million in 2018. An indicator that better describes this problem and is often used is the ratio of the number of insured persons to the number of pension beneficiaries, which is shown inchart 2.

Source: HZMO (2019)

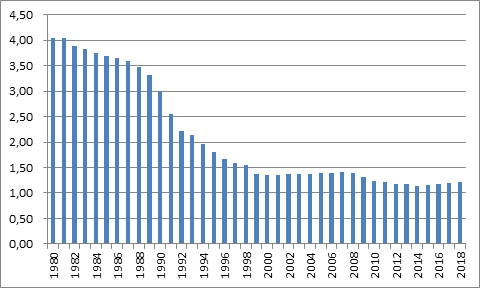

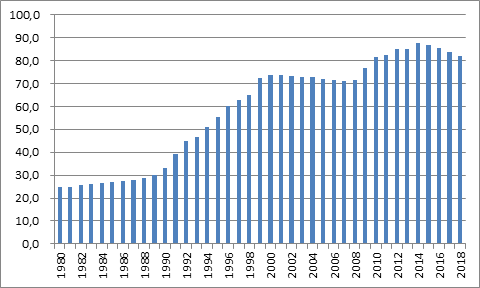

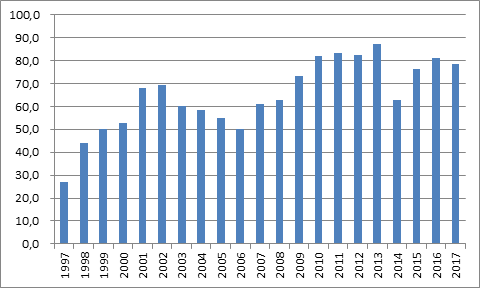

In 1980, 4.04 insured persons paid contributions to one pension beneficiary. Funding for the pension system was significantly different in such circumstances than it is today, when only 1.22 insured persons pay contributions to one pension beneficiary. Although the most noticeable negative change occurred from the beginning to the mid-1990s, this ratio has been in constant decline throughout the period under review. As early as the 1980s, this ratio had fallen by more than 25 percent, or decreased from 4.04 to 3.00. In addition to the economic reasons and retirement conditions of that time, an important share in the mentioned change can be attributed to the factor of declining birth rate, or changes in the age structure of the population. This factor influences the decrease in the ratio over the whole observed time. A relatively larger decline, but in absolute terms very similar, occurred during the transition crisis and the war: from 3.00 to 1.81, or almost 40 percent. The decline in the ratio continues all the time, which indicates even more unfavorable ratios between the number of insured persons and the number of pension beneficiaries. The number of pension beneficiaries per 100 insured persons is shown inchart 3. This number is also called the system dependency ratio.

Source: HZMO (2019), author processing

The system's dependency ratio in Croatia since the second half of the 1990s is among the highest in the world. The figure of 82 pension beneficiaries per 100 insured persons in 2018, and its continuous increase since 1980, confirms two already pointed facts: first, that in the foreseeable future the number of pension beneficiaries will be equal to or greater than the number of insured persons, and second, that the amount of contribution based pensions will be so small that it will not be sufficient for life. Namely, assuming that the number of insured persons and the number of pension beneficiaries are equal, at the rate of 15 percent of the allocation for the first pension pillar, ie the generation solidarity pillar, the total cumulated pension funds will make up 15 percent of the total salaries. According to this, the average pension, if financed solely by contributions, would be in the amount of 15 percent of the average salary, which would lead to very unpleasant social consequences.Chart 4 shows the trend in the share of the average pension in the average wage over the last few decades.

The average pension was decreasing by the end of the 1990s, and since then has remained stable at around 40 percent of the average wage. In 2018, it amounted to approximately HRK 2,640 and amounted to 42.3 percent of the average salary. It should be noted that the average pension consists of old-age, invalidity and survivors' pensions, and that the old-age pension is about five percent higher. However, it is a low level of pensions that leads to a difficult life for retirees and causes dissatisfaction with its comparison with length of service and years of payment of pension contributions. Further reduction of the average amount of pensions is therefore not realistic not only because of possible resistance, but also because of the fact that this would increase social problems. A system of generational solidarity in which costs and revenues are balanced can be expressed by the following equation (Willmore, 2004):

pR = swL

where p is the average amount of pension and R represents the number of pensioners. On the left side of the equation are system costs and on the right are funding sources. The contribution rate s, multiplied by the average wage and the number of employees L, represents the mass of funds collected, ie the sources of financing the pensions paid. From the previous equation, the required contribution rate can be calculated with the desired ratio of average pension to average salary and the ratio of number of employees and number of pensioners:

s = (p / w) / (L / R)

With productivity and wages rising, so are pensions, so the system is in balance as long as the number or ratio of employees and retirees is constant. As this ratio worsens, that is, the number of pension beneficiaries increases or the number of employees decreases, the system becomes unsustainable. It is necessary to either reduce the ratio of pensions to wages, which means reducing them realistically, or increasing the rate of appropriation to maintain the existing level of pensions. Both measures are limited because neither the appropriations can be raised indefinitely nor the pensions can be significantly reduced.

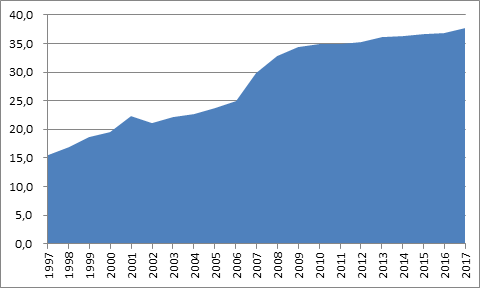

The solution is either to raise the contribution rate, which would have a direct and negative impact on competitiveness and economic growth, or change the way pensions are funded through a change in tax structure. It should be borne in mind that raising the contribution rate has an economic margin of efficiency and that it would be a measure that would only temporarily solve the problem and would significantly impair competitiveness and jeopardize other macroeconomic objectives. Grdinić et al (2017) find in the sample of former transition countries the negative and statistically significant effects of social security contributions on economic growth both in the short and long term. Crnogorac and Lago-Peñas (2019) warn of the problem of the informal economy and tax evasion caused by an irreversible tax structure. Deskar-Škrbić (2018) goes a step further and finds that fiscal policy plays a very important role in stimulating the Croatian economy. Kotlikoff (2011) believes that the system needs to be thoroughly reformed because partial measures can hardly bring a viable solution. Moreover, he believes that the partial measures will make the situation even worse and that future generations will find the system in an even more difficult state than it is today. On the other hand, frequent changes in the tax structure suggest a precarious institutional environment that is considered one of the main derivatives of the economic growth of national economies (Buterin et al, 2018).Chart 5 shows HZMO expenditures for pensions and retirement benefits.

Despite pension reforms, pension expenditures in the 21 observed years increased almost threefold, from HRK 15.4 billion in 1997 to HRK 39.2 billion in 2018. As this relative and absolute increase in the amount for pensions was not accompanied by an increase in the contribution rate, and there was no increase in the number of insured persons, it is clear that the pension system lacks the money to function and must be moved from somewhere. Over the past three decades, several significant changes in the amount and manner of collecting pension contributions have occurred, and are presented intable 1.

| Year | Contributions from salary | Contributions on salary | In total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 9,50 | 9,00 | 18,50 |

| 1991 | 11,00 | 11,00 | 22,00 |

| 1994 | 13,50 | 13,50 | 27,00 |

| 1995 | 12,75 | 12,75 | 25,50 |

| 1998 | 10,75 | 10,75 | 21,50 |

| 2000 | 10,75 | 8,75 | 19,50 |

| 2003 | 20,00 | 0,00 | 20,00 |

Source: HZMO (2019a)

Since 2003, the pension contribution rate has not changed, totaling 20 percent. Insured persons in both pension pillars pay three quarters into the first pillar and one quarter into the second pillar. Although since 2000 there have been only salary contributions and no more salary contributions, both for the insured and the employer, this is generally not relevant. Namely, for both the worker and the employer, the amount of pay is important, one as income and the other as a cost category. While workers have the perception that wages are low and that work is poorly paid, employers have the impression that the same work is very expensive. Since contributions reduce net income, they are unpopular and considered as benefits to the state, and it is less important whether they are paid by the employer or the worker.

With the introduction of the second pillar, which pays a quarter of the revenues, since 2002 a transition cost has been incurred, that is, the long-term cost of the state related to the settlement of the deficit in the first pillar. The lack of money is covered by the state budget, and chart 6 shows how much HRK is paid for pensions and pension benefits for every HRK 100 collected pension contributions for the first pillar.

Since for every HRK 100 contributions collected, in order to pay pensions and pension benefits, it is necessary to provide around HRK 80 in the budget, it may be asked whether the pension system in the Republic of Croatia is still based on the German model of generational solidarity. The unfavorable ratio of insured persons and pension beneficiaries, which implies an insufficient mass of pension payment contributions, has led to the need for budgeting to be understood in itself. These interventions are increasing year by year.Table 2 shows the comparative movement of pension expenditures and contributions and budget revenues.

Pension expenditures grew by 173.2 percent between 1997 and 2017, and contribution income grew by only 73.5 percent. To make up for that difference, budget allocations have increased more than tenfold. In 1997, the share of appropriations in pension expenditures was 11.9 percent, and by 2017 it had risen to 44.0 percent. Despite the increase in contributions collected in absolute terms, the focus of pension payments is slowly but surely shifting from contributions to taxes.

4. Conclusion

All the data presented indicate that contributions can be less and less counted and that in Croatia the system of generational solidarity as such, at least when it comes to pensions, does not exist in its original form. The payment of pensions and the functioning of pension insurance are increasingly dependent on Croatia's budgetary capabilities, so significant system reforms need to be made to take into account the objective constraints on the age structure of the Croatian population and the importance of the impact of the tax structure on the competitiveness of the economy.

The features of the major changes made to the Pension Insurance Act so far and a series of minor changes to the relevant laws are attempts to reduce the financial pressure in the long run, that is, attempts to create the assumptions for the long-term sustainability of the system. However, due to problems on the revenue side of the system, such changes do not mean much in the long run. The demographic problems faced by Croatia are directly linked to the future functioning of a pension system based on generational solidarity and are one of the factors behind its greatest limitation. Contributions have a distortive effect and, by themselves, adversely affect the competitiveness of the economy. Therefore, substantially increasing the contribution in order to possibly better fill the first pillar, that is, the pillar of generational solidarity, is neither a realistic nor economically wise nor justified option. Resolving the demographic issue is certainly at the heart of resolving this issue, but the effects of a pro-natalist policy would only be noticeable in a few decades, if it were to be adopted and successfully implemented. In the meantime, it is necessary to ensure the functioning of the system, that is, to take care of the revenue side in the conditions that are given and which can be predicted with greater or less certainty. This means that there is a need to change the regulatory framework, which primarily means a change in the tax structure and a shift from income taxation, ie from the collection of pension contributions towards a greater reliance on consumption taxation.