INTRODUCTION

Globally, open data has played an important role in creating social and economic opportunities, solving public problems and empowering citizens to make better decisions[1]. An example of this is the United Kingdom, where heart surgeons of the National Health Service published comparable data on individual clinical outcomes in 2004. In 2011, improvements are reported; the survival rate increased by more than a third[2]. Another example is Nepal where open data regarding aid flows – expressed in geographical information – have contributed to building a transparent and accountable public institution after the civil war[3]. Likewise, within the European Union, open data is considered important for socio-economic developments of the society[4]. Recently, the lack of effective data use to address the COVID-19 virus shows that this important development still requires further work. In April 2020, 500 data practitioners and organisations over the world engaged in the ‘Call for Action’ by GovLab, a big data think tank, to develop an open data infrastructure which is capable of challenge the pandemic and other dynamic threats[1].

The majority of the data which is considered most valuable for tackling dynamic threats in the world is generated and held by the private sector – collected and controlled behind closed doors[1]. Interestingly, most global, regional and national efforts on opening data focus on open government data (or public sector information, PSI). It is expected that the value of open public sector information in Europe will increase from € 52 million in 2018 to € 194 billion in 2030[5]. However, in order to answer pressing public questions on dynamic threats data publicly obtained needs to be open, central and incorporated into both public and private sector[1-4]. The growing demand for open data is starting to have an influence on the open data policy of the European Union. The scope in the new open data directive is not limited anymore to public sector organisations, but was extended to other sectors.

In 2019, open data and the re-use of PSI was enacted in a new EU Directive, the Open Data Directive (ODD). The ODD provides a common legal framework for a European market for government-held data[4]. It builds on the Directives of 2003 and 2013, that focused on the re-use of records from public organisations, including national archives and libraries[6]. The new ODD also applies to documents held by public undertakings, research performing organisations and research funding organisations. These are non-government parties that collect, produce, reproduce and disseminate documents to provide services in the general interest[7]. Most often the data policies of public undertakings are restricted, not open data policies. The provisions of the new Directive are not yet mandatory for public undertakings. However, one may expect that new legislation will be more strict in the future. For the Netherlands to comply successfully with future legislation the challenge is to identify the barriers and means of tackling them for public undertakings to achieve an open data policy in the future.

In this article the following research question is central: “How can public undertakings in the Netherlands overcome the barriers to opening their datasets in order to be prepared for expected future legislation towards open data for public undertakings?”

We applied a mixed method research methodology. First, we conducted a comprehensive literature study on various concepts of open data and openness of data, barriers of open data, and the open data directive. This resulted in a first draft openness level model. Then we conducted interviews to review the open data status of three public undertakings and mapped their status on the openness level model and highlighted barriers to be overcome to move to the next level. In this last step, we used the experiences of a best practice open data public undertaking.

In this article we first explain open data and the open data directive, and present three levels of openness. The following section addresses the barriers one may have to tackle when moving from one level of openness to a next. Then, we assess the current level of openness of three Dutch public undertakings and explore the barriers they may experience when opening up their data ultimately by adhering to the requirements of the EU open data directive. The article concludes with the conclusions and recommendations for further research.

OPEN DATA (DIRECTIVE)

Open data is data that does not have any barriers in the (re)use. Open data aims to optimize access, sharing and (re-)using data from a technical, legal, financial, and intellectual perspective[8].

In the European Union, the Directive on the re-use of public sector information (PSI directive 2003/98/EC) was central to the stimulation of open government data. It was, however, only after two revisions that open data was introduced in the Directive on open data and the re-use of public sector information[7]. Re-use of documents held by public sector bodies should be provided in principle free of charge, and not be subject to any conditions in the re-use. High value datasets, documents associated with important socioeconomic benefits having a particular high value for the economy and society, shall be available free of charge, provided va APIs and as a bulk download.

The Directive’s focus has been on documents of public sector bodies. However, the scope of the Directive has been extended from solely public sector bodies to educational and research establishments (schools, universities) and cultural establishments (libraries, museums and archives) in 2013 to public undertakings in 2019.

Public undertakings collect, produce, reproduce and disseminate documents to provide services in the general interest. At this moment, the Open data directive applies to public undertakings operating in the transport and utilities sectors only. Organisations operating in these sectors may decide themselves to release their data for re-use. For these data available for re-use a limited set of obligations is applicable, as compared to the general PSI regime. Public undertakings, for instance, can charge above marginal costs for dissemination, and are exempted from the general procedural rules on how to process requests for re-use.

However, the first PSI directive of 2003 exempted documents from educational and research establishments and cultural establishments explicitly, then brought the educational and research establishments and a major part of the cultural ones (libaries, museums, archives) under the scope of the first revision of the PSI Directive 2013/37/EU with very similar voluntary provisions. In the last revision, several of the voluntary provision were replaced by requirements: for example, documents of many educational and research establishments should be available for re-use and in principle be provided free of charge. A similar development can be foreseen for documents of public undertakings.

In order to assess the effort a public undertaking has to undertake to move from its existing data sharing policies towards full open data policies, we developed a framework identifying three levels of openness.

LEVELS OF OPENNESS

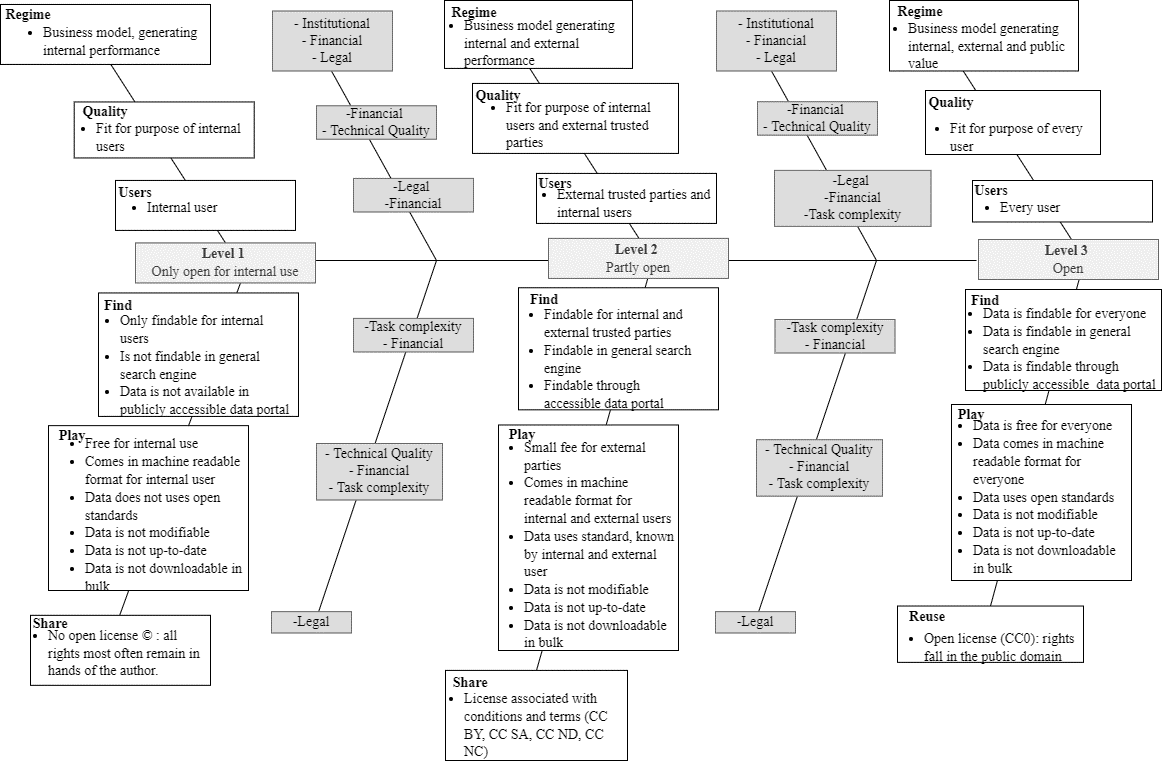

The definitions of open data from the literature review were used as an input for the creation of a multi-dimensional model on distinct levels of open data, Figure 1. Three levels of open data were identified: (1) only open for internal use, (2) partly open for external users, and (3) fully open data. To specify the requirements of the three levels, we used the sub categories of find, play and share from[9]. Find and play are associated with how the data can be found and used, whereas share is associated with the person using the data and how the data can be shared.[9] claims that once data is found and used, it should be possible to share it with others[9]. However, when considering openness level three, ‘sharing’ was replaced by re-use since sharing does not imply that the data can be re-used by all, which is a requirement of the Open data directive[7].

At the first level data is considered not to be open at all and only accessible for the internal user. Here, the data cannot be found through a general search engine[10]. This makes the data invisible to everyone but the internal user. The absence of an open licence makes it impossible to share the data with external users[9,[10,[12,[13]. This suits an internal regime that is focussed on using the data for internal purposes, limiting the data quality to the purpose of the internal user[14].

In the second level of openness, partly open for external users, the data is under strict conditions available to external parties: the metadata of the data is published in publicly accessible data portal and/ or search engines, in a machine-readable format[10]. However, fees may be charged and the data can only be shared under certain conditions and terms. This data policy generates both internal and external value.

In the most open level, open data, the data is adhering to the most fundamental principles of open data: free of charge, no conditions in the re-use, data is downloadable in bulk, adhering to open standards, among others. The data is findable through a general search engine and data portal, free of charge, comes in a machine-readable format and with an open licence so that everyone can re-use the data[7,[14,[15. At this level, internal-, external-, as well as public value are generated. This third level is most closely following the requirements of the Open Data Directive.

MOVING FROM ONE LEVEL OF OPENNESS TOWARDS ANOTHER: ADDRESSING OPEN DATA BARRIERS

While open data can contribute to social and economic benefits, moving from a lower level of openness to full open data will encounter numerous barriers[1,[16]. To achieve open data these barriers need to be identified and overcome. These barriers can be perceived from either the provider’s perspective or the user’s perspective[10,[11,[16] We identified three types of barriers: (1) institutional barriers, (3) task complexity barriers, and (3) technical quality barriers.

INSTITUTIONAL BARRIERS

Any unwillingness from data providers in terms of financial and legal risk to make data open available, is known as an institutional barrier[16]. Institutional risks like this make organisations cautious when providing data[17]. Such a risk-averse culture results in organisations preferring not take any risk to change[16,[18].

Perceived financial risks can be divided in two categories: (1) fears for budget deficits due to the loss of income when a cost recovery policy needs to be replaced by an open data policy, and (2) the expected extra costs related to additional human and financial resources both to collect, to maintain, to process the data and finally to distribute it as open data[19]: adaptation costs, infrastructural costs and structural maintenance / operational costs[11,[19].

Legal risks of open data are manifold: higher liability risk due to errors in the data, misuse of the data, disclosure of secured information, such as trade secrets can put an organisation at risk[20], violation of data protection stated by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or privacy legislation, breaches of existing contracts, and/or open government data unfairly competing with similar datasets sold by a company. An example of unexpected increased liability risk was in Pacific Gas & Electricity (PG&E), an American utility company that published their data without any restrictions toward the use of the data. After a spatial analysis, done with open data from the company on the electricity poles, PG&E were held liable for the cause of the largest and most destructive wildfires in state history. The study showed that the locations of the fires were often in the proximity of the electricity poles from PG&E (energy data request from public datasets from PG&E). Their equipment of electric powerlines across the state evoked sparks that caused wild-fires which took the life of 84 people in 2018[21]. In 2020, PG&E pleaded guilty and agreed to pay a maximum fine of 25.5 billion dollar for losses from the 2018 wild fire, blamed on the crumbling equipment of PG&E[22]. On the one hand it can be stated that open data is used correctly in this case by directing to the cause of the wildfires in California in 2018. On the other hand, this example highlights that, from a data providers perspective, there are risks associated with open data.

TASK COMPLEXITY BARRIERS

Finding and using data tends to be challenging and often complex for the data user, due to high complexities. These complexities are worsened when there is no explanation of the context of the data or when the data formats and datasets are too complex to handle[11,[16,[18]. For example, complexity becomes a barrier in geographical datasets for an unexperienced user when attempts are made to open an AutoCAD drawing (a detailed 2D or 3D illustration) in a geographical information system (GIS, ArcGIS pro for example). Matching of data formats with information systems can become more challenging and require more user knowledge/experience to manipulate the data.

Therefore, use of data is considered only for those with domain knowledge which allow for opening, using and interpreting the data[16]. So data can only be accessed and used by a user who has the technical skills to download the data, open the data in a GIS and analyse the data through tools. The format and complexity of data may contribute to a digital divide, a barrier, as the use of data might be limited to certain groups; only those with domain knowledge[16]. User skills is a potential barrier that can be tackled by improved data format, structure and utility.

TECHNICAL QUALITY BARRIERS

In order for the data to ensure a valuable return on both user and provider side, the data needs to be fit for use[14,[23]. Because every user may have a different purpose when using data, a guarantee of quality cannot be given[16,[18]. An accuracy check on the data needs to be done before the data can be used for a certain purpose. Such a check can be accomplished through contact with the data creator and by enquiring about the correctness of the data in terms of the completeness of the metadata[16]. Often this is not possible as contact information, if present at all, does not trace back to the actual data creator[11,[16]. Even when the metadata is present sufficient data quality is not guaranteed as there is no single standard for metadata for all usersresulting in heterogeneity of metadata models and different vocabularies[11]. At worst, this could limit or prevent the user from reusing the data[16]. The absence of agreed quality standards, possible lack of a supporting infrastructure (data portal), as well as fragmentation of manipulation software and applications can present technical barriers to data openness.

SUMMARY OF BARRIERS & LEVELS OF OPENNESS

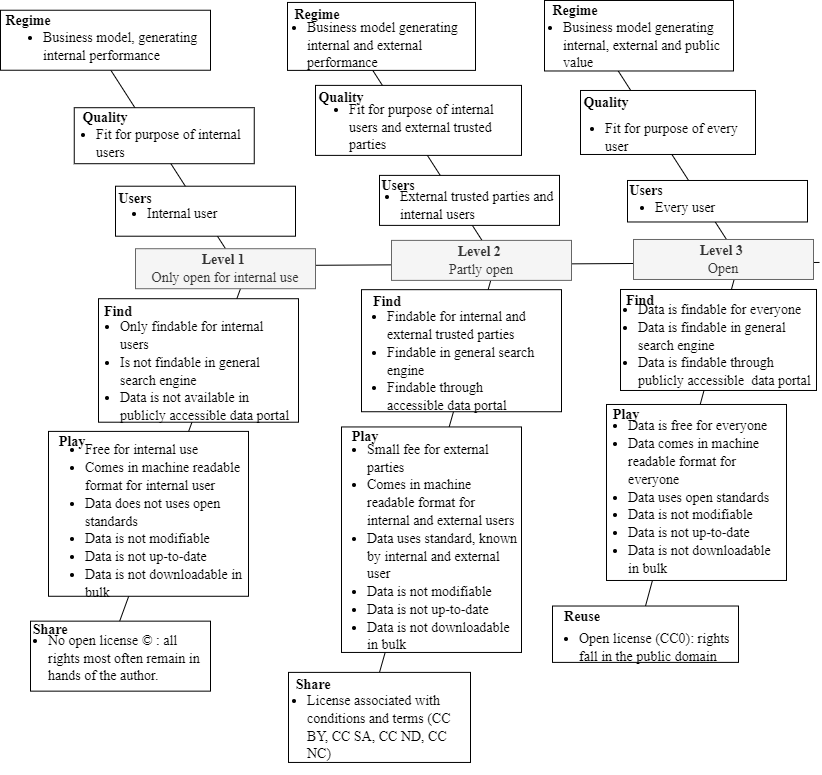

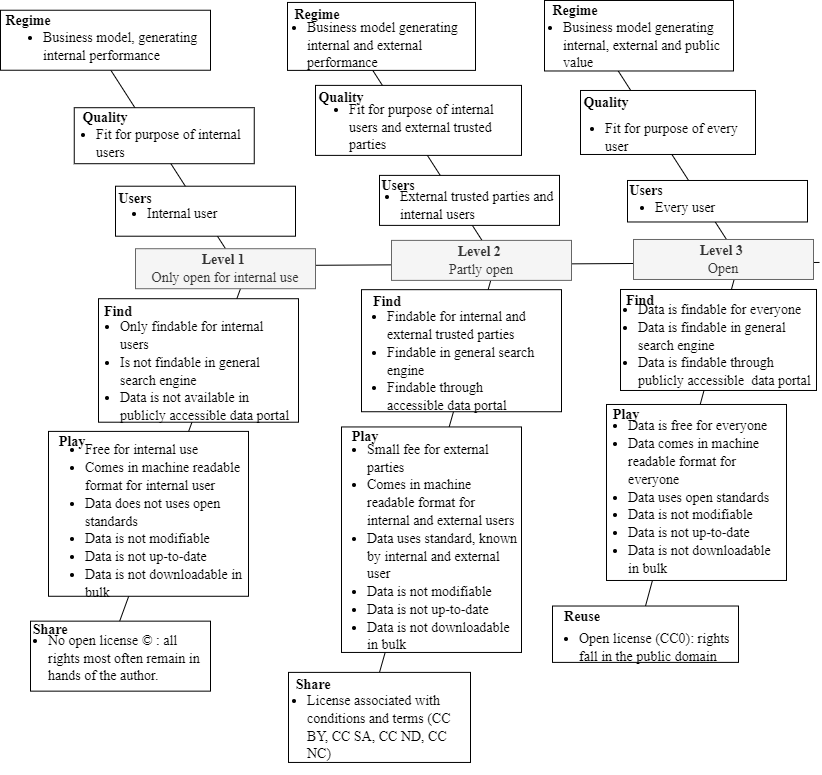

The barriers together with the different levels of open data identified so far are presented in Figure 2. Firstly, it shows the organisational barrier that affect the attainability of the data, which is addressed by the data provider in terms of regime, quality of the data and the type of user (the upper part of the model)[24]. A regime may face institutional, financial and legislative barriers when steps towards an open data policy are made[2-[27]. Creating an open data regime requires willingness of the data provider to do so and this includes finding financial funds and applying licenses that allow the user to share and re-use the data[16,[17,[25]. In order to create more openness through improved quality of the data, improving attainability and usability, financial and technical barriers need to be tackled. To modify the quality of the data for external and public users technical skills are required as well as financial resources to adjust the quality to the purpose of external and public users[11]. Legal barriers may be faced when changes in licence are required enabling the sharing of data with external trusted parties whether or not under conditions. This is due to the fact that external parties also have the rights to access and modify the data through a new licence. Therefore, new legal barriers are faced for the data provider to limit data misuse and data fragmentation, which might be caused by external parties as a result of more rights. When legislation does not prevent the re-use of the data for every user anymore, there are liability risks for the data provider when the step towards level three is taken. These risks can be expressed in financial, actual and/or reputational damage from false conclusions drawn from the data by the users, or from publishing private and secure data[28]. Financial barriers are encountered when making the data findable and accessible through search engines and/or data portals for external users. Barriers associated with task complexity are faced when the users shift from being external trusted parties to public users as the data user is unknown to the data provider in level three. The domain knowledge of the user is difficult to assess which makes it is difficult for the data provider to know whether the published data suits the knowledge domain of all the user[16].

As a result of the barriers perceived by the data provider, the ability for the data user to find, play with, and share or re-use the data can decrease. In order to make the data more findable for users other than the internal users, the data providing organisation faces financial and task complexity barriers. The same barriers are faced when it comes down to play. Financial investment by the data provider is required to create the possibility for the user freely to use and modify the data. The additional barrier of technical quality is faced by play since the published data need to be recent, in a machine-readable format and possible to be downloaded in bulk. The barriers faced by the requirements of share/re-use are associated with the application of different types of licenses as this decides whether and under which conditions the data can be shared and re-used. The attainability of the data for the user is determined by the data provider[24,[28-[31]. Figure 2 shows the possible barriers between levels of openness, based on the literature review.

OPEN DATA IN THREE PUBLIC UNDERTAKINGS

In this section we show the results of a case study in three Dutch public undertakings. We performed interviews with one Analytics Specialist, two Data Stewards, a GEO-IT solution architect, an Enterprise Data Architect and a Product Developer. We reviewed the level of openness in these organisations, and the perceived barriers to move to a next level of openness.

PORT OF ROTTERDAM

Port of Rotterdam (PoR) is the biggest sea harbour of Europe, situated in the Harbour of Rotterdam. The harbour has deep-sea connections with more than a thousand harbours around the world. The Port Authority has an important role in developing, organising and managing the logistic activities in the Harbour. PoR’s shares are held by the Municipality of Rotterdam (70 %) and the Dutch government (30 %). The shares are not listed on stock exchange which makes PoR an unlisted public limited company.

Regarding the different open data levels, Port of Rotterdam can be placed in the situation prior to level 1. Although data is shared with internal users, it is not yet shared with all internal users. Data is collected within departments and typically not shared with others within PoR. Data is only shared with third parties when this is in the interest of PoR’s business activities. Until now, data has never been shared with citizens exclusively to generate public value. Awareness of the value of sharing data is growing within the company. This has resulted in 12 data domains which should create an overview of the data that is used by the departments and the impact it has. When this task is completed, a next step will be to create more openness towards third parties to generate both internal and external performance. Sharing data with citizens for the sake of generating public value on its own is not yet on the horizon. This next step will be towards level two of the different open data levels, dealing with, in order of significance to PoR, technical and institutional (including legal) barriers, Figure 3. Legal barriers are not considered to be the biggest issue since PoR controls the conditions and terms that can be determined in the data delivery agreement. Technical issues, however, are considered difficult barriers to deal with since a new technical department needs to be developed to make the data more findable through a portal for third parties (between ‘find’ and ‘play’ in Figure 3). The quality needs to be fit for the purpose of third parties which requires additional investments of PoR. The willingness to share data with external parties is growing within the company, but still is not for granted, placing the institutional barrier not on the top of the list. The drive to share data is there but the next step is to find the most suitable technical and financial solution for it. As yet, level three, where data sharing is replaced by data re-use and the user is identified as everyone, is a step too far away for Port of Rotterdam.

SCHIPHOL

Amsterdam Schiphol Airport is the largest airport in the Netherlands and plays an important economic and social role in Europe. It is considered one of the most connected airports in the world and facilitates 332 international connections. Regional airports, international alliances and cooperation enhance this international connection. Schiphol is held by the Royal Schiphol Group, with the Dutch government, the municipality of Amsterdam and Rotterdam and Groupe ADP (an airport operator) as stakeholders.

Schiphol can be placed in level two of the multi-dimensional open data model. The goal of their data governance is to share data with internal, external and public users. Sharing data with

the public user is, however, only executed when there is no interference with the commercial interests of Schiphol. Sharing data with external trusted parties is possible and comes with an agreement that covers liability issues regarding misuse of the data. For the public user the available datasets are presented on the open data portal of Schiphol. Even though the data is available for the external and public user, it is not directly accessible and so it cannot be ‘re used’. To control the data used by the public user a data request – subsequently a registration – is needed from the user. After a request, the data is provided to the user with less meta data and a lower level of detail than the source data, controlling the sensitivity and amount of data provided to external users.

Perceived barriers that Schiphol associates with the next step towards open data concern security and privacy barriers, confidentiality barriers and institutional barriers (see Figure 4). The interviewees highlighted that the main issue that causes the privacy and security barriers is the level of detail of the data. This applies first of all to the security barrier. The available data reveals too much detail, such as the location of the armoury, that could assist a terrorist attack. Secondly, too much detail can reveal private data about individuals at Schiphol which places these data under the scope of the GDPR, which does not allow for open data (level three in the model). Confidential agreements with third parties cause the third legal barrier. Schiphol cannot share data that is retrieved from third parties if re-use is only allowed by internal users of Schiphol; this data cannot be shared with others. Lastly, due to fear of false conclusions drawn from the open data of Schiphol, not all data is made openly available. This is an institutional barrier. Both interviewees state that Schiphol has already experienced reputational damage as a result of false conclusions drawn by users and, as a result of that, they are not willing to adapt to a fully open data regime. However, it could be argued that publishing open data could prevent reputational damage. By publishing open data, Schiphol creates the opportunity to provide good and correct data, which can prevent the risk of false conclusion drawn by the user. So instead of fearing open data, it could also be considered a solution.

In contrast to the Port of Rotterdam, financial, technical, and quality issues are not considered to be the main causes for the barriers faced by Schiphol. These barriers are listed as numbers four, five and six – associated with ‘quality’, ‘find’ and ‘play’, in Figure 4. Financial issues due to development and maintenance costs of open data are not considered since costs for developing and distributing data for public use are already made and not considered a great issue. A technical quality barrier will also not be the main problem since Schiphol already succeeded in setting up a data portal for the users (developer.schiphol.nl). Technical quality barriers are not faced in the sense that modification of the data for public use is not possible; it is possible but does take some time and effort.

LIANDER

At present, for most organisations it is clear what open data is, and which social and economic values it can offer[4]. However, ‘open data’ is not a sort of package that organisations can buy in a shop that comes with instructions on how to apply it. This raises the question how organisations can best share their data or even provide it as open data. Since data sharing is relatively new, hard facts and figures are not yet available to indicate the best way of data sharing. It is often best to learn from the success of other organisations by learning how they overcame the barriers to open data. This was acknowledged by the European data organisations who focussed on data sharing for both governments as well as private organisations (Data.overheid.nl, user meeting, 2020).

One public undertaking that has successfully opened their data is Liander, which is a Dutch utility company and subsidiary of Alliander, which develops and manages energy networks. Liander is allowed to operate as an independent grid operator, however, the activities cannot be in conflict with the national grid management. The company is providing open data since 2014 and define open data as digital data that is made available for everyone through the internet[32].

The motivation to provide open data needs to be very clear. Liander wanted to contribute to a better collaboration with the regions within their area of operation[32]. Furthermore, it was motivated by the social benefits open data brings to the society. Liander often received individual questions regarding the utility usage of their network and the bottlenecks within their network. These requests needed to be answered one by one which resulted in a time consuming activity for Liander. By publishing their most sought-after data they wanted to create more opportunities for the users (such as municipalities) to work with their information without having to ask Liander for input every time. With data readily accessible, the user can work with Liander’s information and substantiate their own plans with meaningful data. In turn, such plans could benefit to Liander’s network. This potential societal benefit was the main motivation for Liander. Saving time on individual data questions was also considered a motivation to continue to provide open data. The other motivation arose from the fact that Liander wants to contribute to energy transition. Providing open data on for example consumption per year, per type of house can give an understanding on the best possible manner to lower the energy consumption. Since Liander mainly provides their own collected data and not data from external parties, they do not face the same issue of sharing confidential data from clients as Port of Rotterdam and Schiphol.

The first question that needs to be answered is whether sharing of data is allowed under the law. Similar to Port of Rotterdam and Schiphol, the fear of liability issues was present. Although Liander has experienced significant objection to data sharing from different Dutch legal authorities, liability issues were never experienced. The disclaimer used for the open data (Creative Commons BY) may be an explanation for this.

Similar to Schiphol Airport, the fear of terrorism also affects Liander’s data. In order to get approval for such issues was discussed with the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD). After years of discussion, the AIVD decided which of Liander’s data could be published and which data could not be published. The AIVD imposed aggregation of the level of detail that was publicly available. The AIVD decided that the electricity cable network could be published, whereas the location of the gas pipes was considered too sensitive to publish in terms of explosion risk. Although it took years for Liander to satisfy the requirements of AIVD, the willingness to provide open data never gave way to fear for legal or terrorism issues according to the interviewee.

Another legal barrier was in potential unfair competition. In the Netherlands, the ACM (consumer association authority) ensures a fair balance between companies and protects consumer interest. Initially, the ACM considered the E-Atlas of Liander as a distortion of competition: unfair competition. The fear was that other companies would be disadvantaged in their business if Liander put a similar business to the market, financed by public funds. In practice, this was not the case as other businesses were not allowed to access this source data on electricity and gas usage due to data protection legislation. Due to market barriers, not related to data, other companies could not start a similar business. In this case unfair competition could not result from data issues.

Technical barriers were not an issue for Liander when setting up an open data portal. “Setting up the open data portal is done by internal employees so no extra, external costs are made”. Moreover, the data portal was developed by the internal employees to reduce the time spent on previous data requests. Therefore, the internal time spent on the development is an investment to win time in the future. The internal expenses were estimated at 0,5 FTE. Ignoring opportunity costs and since these costs were made already, no additional financial issues were faced by Liander.

Feedback on the quality of the data is actively encouraged by Liander as it gives information on the quality requirements of the user. Moreover, the feedback given by the users can be used to improve the quality of the data so that other users will not face the same issue.

The case of Liander proves that consistent determination to provide open data is key to achieving it. Liander faced mainly legal barriers associated with the level of detail of the data they could provide. The initial level of detail of the data interfered with both the guidelines of the AIVD and the GDPR. Aggregation of the data was key for the organisation to ensure open data without breaking the legal protection and privacy guidelines. In their action plan towards open data they dealt with legal, technical and quality issues that were challenged with data aggregation and legal discussions. By opening up Liander’s data, the company experienced benefits in time and money saved on individual data request. Providing open data contributed to the energy transition because Liander’s data informed on possible manners to lower energy consumption. Liander considered providing of open data a social benefit and which was a key motivating point. The next chapter assesses whether Port of Rotterdam and Schiphol could apply this working method as well in order to achieve open data.

DISCUSSION

The Liander experience indicates that aggregation is an important tool to achieve open data that complies with legal requirements in terms of privacy, security and confidentiality of data. A discussion point could be whether open data can still be achieved without the option of aggregation. For PoR this could apply to the less sensitive datasets classified as ‘public’ instead of ‘internal’ or ‘confidential’. This could, for instance, be the case for the datasets on traffic signs as often used by PoR for internal purposes. Within this dataset, all attributes such as model number, location, and year of placement are classified as public; no aggregation is needed to provide this data as open data. Other datasets which seemingly do not hold confidential data, such as road networks, may prove otherwise. The dataset on the road network holds several attributes which are classified as public such as the road type, function, length, and hardening layer, but this dataset also holds confidential information, such as inspection results and level of ambition (the desired maintenance level of the asset). For Schiphol, the same could be considered. Is it possible to open up datasets which presumably do not hold sensitive data? Of all the datasets on which Schiphol is currently working it may be possible for the dataset on flying birds. The approach could be that this information has no potential provoke terrorism or breach the requirements of the EU General Data Protection Regulation. This approach could be applied to more datasets than the flying birds. Moreover, without the possibility of aggregation it might be possible for both companies to provide open data through the CC-BY licence, as done by Liander. Since this licence allows re-users to distribute adapt, and build upon the data if attribution is given to the creator, it could remain a sense of control for the companies. This way, it becomes clear for what purposes the data is used and by whom.

The lessons from Liander show that at the heart of open data sits an open data mindset; a fundamental belief in the concept that openness of data is desirable and a service to the common good. PoR and Schiphol, as mostly publicly owned organisations, could reasonable be expected to adopt a more socially responsible approach to their data. Liander’s experience showed a more holistic approach to data by considering the cost of responding to questions in combination with the cost of data openness. They showed that the added expense was limited and outweighed by commercial as well as social benefits.

Liander also showed that careful management of accessibility of the data, for instance by aggregating, mitigates the risk to reputation and could be off-set by the benefit of being regarded as a transparent, accountable and socially responsible organisation. As a grid operator, Liander is a ready target for potential criticism, for instance on climate impact. PoR and Schiphol, being less open with their data, but still significant potential targets for criticism, could benefit a more pro-active approach to open data. A pro-active approach to open data could anticipate such accusations and potential reputational damage. Hence, they could point at the readily available data; this is often sufficient to deflect more detailed investigation. For example, for Schiphol this could be done by providing correct data on road networks to avoid false conclusions drawn by the users, subsequently the media. The cost effort in responding to media or legal challenges, both in direct financial terms but also in reputational terms, should be included in the equation when considering data openness.

Finally, the pressure to open up data in public and semi-public organisations will continue to accumulate. Both PoR and Schiphol would recognise the unavoidability of moving toward open data. Early recognition of the inevitability investment requirement would still give them an opportunity to plan, schedule, implement and finance their open data programme at their own tempo. Once regulation overtakes their effort, the tempo will be set from outside and may be less optimal.

CONCLUSIONS

In this research the following research question was addressed: “How can public undertakings in the Netherlands overcome the barriers to opening their datasets in order to be prepared for expected future legislation towards open data for public undertakings?”

It can be stated that public undertakings, such as Port of Rotterdam (PoR) and Schiphol Airport, can overcome barriers towards open data to be prepared for the foreseen future legislation of the Open Data Directive. However, to do so changes need to be implemented. The multi-dimensional model in this research identified three different levels of open data for a public undertaking to reference it’s data policy: (1) only open for internal use, (2) partly open for external users, and (3) fully open data. In this model the requirements of open data are interpreted from the data provider’s perspective in order to make the data more open for the end-user. At the first level data is only accessible for the internal user, using the data for internal performance; such data cannot be found through a general search engine. At the second level data openness is improved as it is findable and accessible through a general search engine or data portal, available for the external data user as well as to the internal data user. Data is used for generating internal and external performance. At the third level data can be considered most open. The data is findable for the internal, external and public user, through a general search engine and data portal, free of charge and with an open licence for everyone to re-use the data.

Neither PoR nor Schiphol are ready to comply with the future rules when the Open Data Directive requirements become mandatory. Barriers still need to be overcome, but Liander has shown that this can be achieved with prolonged leadership. PoR is placed in level one of the model as the collected data is used by and shared with the internal user mostly. Schiphol can be placed in level two since it shares data with internal, external and public users. Sharing data with the public user is, as yet, only executed when there is no interference with the Schiphol’s commercial interests. The main goal of both public undertakings is to generate internal performance with their collected data. In between the levels, barriers are identified which are faced when a higher level is pursued. Identified barriers to be overcome are financial, institutional, task complexity, legal, and technical. For Liander, that provides open data since 2014, similar barriers were encountered and defeated on their path to open data. The Liander case shows that achieving open data starts with the institutional motivation to do so. A commitment to open data must stem from the top level in the corporate body to gain sufficient traction.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For future research it is recommended to take this research as a motive and reset the scope to the outcomes of this research. An interesting feature presented in the results was the use of aggregation by Liander. Aggregation was considered to be the key method to use for the achievement of open data in terms of legal requirements concerning security privacy and confidentiality. One proposed action would be to focus on the level of aggregation, suitable for the current data policy of both PoR and Schiphol. The question to consider would be: to what extent can the level of the datasets be aggregated and still contribute to the internal performance of the companies? This question interprets the level of detail from the data provider. However, the same question could be asked from the perspective of the users: how valuable is aggregated data for users?

Another recommendation derives from the action plan used by Liander to achieve open data. The different legal and technical steps taken in this action plan could also be taken by PoR and Schiphol. Liander’s action plan helped the company to map the different steps and actions needed to achieve open data; it is recommended to set up a similar action plan for PoR and Schiphol. Future research could develop a similar and suitable action plan for PoR and Schiphol that gives insights in the detailed actions needed to achieve open data for these public undertakings.

A final future research question is associated with the three levels of openness. The aim would be to reach the third level of openness since then an organisation meets the requirements of the Open Data Directive. However, for organisations in beginning stages of open data, is it possible to simply ignore the second stage and leapfrog directly to the most open level? Or should organisations first experience an intermediate level of openness in order to be fully equipped and ready for the final stage?