Introduction

A natural landscape is defined by natural factors: climate, soil, water, relief, geological foundation, and flora and fauna (Herlitzius et al. 2009).

Any landscape is continuously exposed to changes caused by natural forces as well as socio-economic activities. By changing just one of these natural factors through human activity, way of life, or the culture of particular social groups, a natural landscape becomes a cultural landscape.

Thus, it can be said that today, most landscapes on Earth are in fact cultural, and the way they develop or change is “an expression of the dynamic interaction of natural and cultural influences” (Antrop 2005:22).

The consequences of this interaction are visible in the strong connectivity in the mosaic of landscape patches and ecological processes (Fu et al. 2006), as well as anthropogenic activities.

In fact, processes that take place in the landscape create patterns and structures, while being driven and directed by the prevailing spatial structures. In short, these are the reasons and consequences of spatial heterogeneity for various ecological processes (Lang and Blaschke 2010).

The structure of the landscape represents a specific combination of parts, that is, landscape patches. The characteristics of landscape structure as a spatial component are easily observed, described and quantified (Blaschke 2000).

This can be done using computational devices, geographical data processing methods, and digital image processing, which have had a great influence on studying the structure or development of landscapes (Lang and Blaschke 2010).

When determining landscape types, two approaches are used: one is based on land cover/land use and the other is based on the synthesis of natural and cultural characteristics using a hierarchical approach (Dumbović Bilušić 2015).

As a result of this, and given the observed features, the more homogeneous spatial parts of the landscape can be determined, which are then classified into landscape types.

The objective of this paper, using the appropriate spatial analysis methods, is to determine individual structural characteristics (

shape, position and

condition) of the landscape patches of Central Lika according to landscape types for the year 2012 and, using regression analysis, to determine the possible correlation between them.

When determining landscape types in Central Lika, an approach based on land cover/land use was applied. Data from the CORINE Land Cover database for 2012 (CLC 2012) were used.

The data point to the natural geographical characteristics and socio-geographical factors of landscape development which are visible in a space, and so are considered in relation to land cover/land use in Central Lika in this paper.

The database (CLC 2012) comprises digital data which refer to parts of the landscape (for example, settlement, pasture, lake etc.), and is divided into data classes. In this paper, all the digital data referring to the landscape of Central Lika were defined as landscape patches of Central Lika.

For the purposes of this research, all data classes referring to the area of Central Lika were divided into various landscape types (for example, the data classes

Pastures and

Natural grasslands were classed under

Grassland). On this basis, each landscape patch of Central Lika was assigned to one of the landscape types of Central Lika.

At the same time, the landscape patches were assigned to individual landscape types, so that they were as homogeneous as possible in relation to each other in terms of their natural geographic features and the socio-geographic factors of landscape development which were evident in the researched space.

All the patches and landscape types of Central Lika used in this paper are available as digital data, and the spatial analysis was efficiently conducted using GIS methods.

In fact, GIS technology enables and provides qualitative, accurate information about the landscape and its characteristics (Olahová et al. 2013), a higher speed and an entire series of additional qualitative and quantitative analyses which would be incredibly difficult to perform without GIS application.

In addition, an analysis of landscape indicators forms a foundation for a comparison of various scenarios in the landscape, and provides insight into specific features of the landscape over time (Paudel and Yuan 2012).

Previous Research

Using different approaches and methods, landscapes and individual parts of landscapes have been studied in domestic and international papers from different aspects, by analysing the structure and function of landscapes over one or more periods of time.

When research is conducted on a landscape, patches or parts of the landscape are studied. Research papers show one or more levels of landscape (for example, subtype, type, and the landscape as a whole), while analyses are usually performed on one case study, for one separate area or in parallel on several case studies, for several different areas.

By applying GIS technology,Lang and Blaschke (2010) analysed three aspects of landscapes (structure, function and development) using various examples or landscapes, that is, using descriptive-analytical and empirical methods in turn. However, in the analysis of structural characteristics for landscape patches in Central Lika,

this paper uses only one appropriate spatial analysis method for each of the observed characteristics (

Shape Index for the

shape, Average Nearest Neighbour for the

position and

Core Area for the

condition ).M. Jovanić (2017) also analysed all three mentioned aspects of landscape on one case study,

the area of Central Lika. Using the methods of spatial analysis and regression analysis, she analysed the characteristics and development of the characteristics of the landscape patches in Central Lika for subtypes and types of landscapes and the landscape as a whole. In papers by other authors (for example,Rutledge 2003,Olahová et al. 2013),

in addition to the above-mentioned spatial analysis methods, a number of others were used.Rutledge (2003)showed a model with a higher number of indicators which were applicable when analysing the patch fragmentation of the landscape, but did not conduct an analysis in a specific, defined area.

By using data for a specific point in time, some researchers have studied the current, modern structure of the landscape.Túri (2010) conducted an analysis of the landscape structure at the patch level. The results of 30 indicators were compared using spatial analysis methods for two areas.Blaće (2015) analysed the development of the landscape structure of Nadin municipality using more than 20 indicators. However, for the sake of clarity, in research showed in this paper one appropriate spatial analysis method was used for each structural characteristic, and suitable attribute descriptions were provided in order to explain the results in more detail.Blaschke (2000) conducted an analysis of the landscape structure using multiple examples, and employed empirical methods when researching spatial-statistical GIS technology methods regarding the connectivity and optimisation of the spatial arrangement of landscape elements.

However, by using data for single points in time, these papers also analysed their structural changes over time. For example,Aničić and Perica (2003), using the photographic content of karst agricultural areas, analysed the structural changes for single points in time over a given period.

By using data for multiple points in time, some authors have analysed changes and the development of the landscape during one or more time periods.Esbah (2009) analysed changes in structural characteristics of patches in an urban area City of Aydin, Turkey, in two observation years (1977 and 2002) by using a larger number of indicators or spatial analysis methods, but did not include the methods of

Average Nearest Neighbour and

Core Area which are applied in this paper.Cole et al. (2018) conducted an analysis of the change in land cover /land use on a case study for the territory of the United Kingdom, during multiple time frames (2000–2006, 2006–2012), based on data from the CORINE Land Cover database. However, they did not analyse any structural characteristics.Paudel and Yuan (2012) conducted a study about landscape development and the ecological consequences of building a metropolitan area of Saint Paul and Minneapolis in the United States with reference to specific years (1975, 1986, 1998, 2006).

In their analysis, they used a variety of data (aerial photography, orthophoto maps, or multispectral satellite images and spatial planning documents). When analysing various objects through multiple points in time, domestic authors have used a variety of data and analysis methods for landscape research.Morić-Španić and Fuerst-Bjeliš (2017) determined the landscape types of a case study, the area of the island of Hvar by combining multiple data types in two observation years (a vegetation map (1975) and CORINE Land Cover, Croatian Forestry data and digital orthophoto maps (2011)), and tracked landscape change trends in the observed period.

This paper uses the GIS model, which has further applications regarding agricultural revitalisation opportunities.Cvitanović (2014) used remote sensing to conduct an analysis of changes in land cover/land use in a case study, area of Hrvatsko zagorje, for the time period 1991−2011.Cvitanović and Fuerst-Bjeliš (2018) analysed changes in land cover/land use in one particular area for the time period of 1991–2011, using remote sensing, GIS, regression analysis and qualitative methods, with the aim of analysing the socio-geographic factors of change.Jogun et al. (2017, 2019) used, among other, remote sensing methods and a simulation model for analysis and projection of land cover changes, when analysed land cover changes in the northern Croatia for the period 1981–2011, and Požega-Slavonia County for the period 1985–2013.

It is especially important to mention works which have analysed data over a time span of 250 years or more, when satellite images were not available and could not be analysed by remote sensing methods. Instead, various other kinds of sources from different time periods were used, which demanded a very specific work methodology. That works also include recent data, which means the time frame of the investigation is indeed extensive.

For a 250-year time span,Olahová et al. (2013) mapped changes in land cover/land use in a case study, landslide Handlová in Slovakia. For more recent years (2003 and 2011), they analysed the changes in the structual characterics of patches of the area using a higher number of indicators. In the first part of their paper,Fuerst-Bjeliš et al. (2000) presented the results of research into anthropogenic influences on the Central Velebit environment over a longer time period (starting before the 17th century) using the descriptive-analytical method.

They performed a diachronic analysis and produced a model of periodization changes to compare individual indicators in various stages of the observed period and analyse their development. In the second part of the paper, based on establishing a synthetic criterion which comprised three geoecological parameters (relative height, length of slope, length index and relative height) and one aesthetic parameter (visibility), by using multi-variant cluster and discriminatory analysis, they conducted a geoecological evaluation of the landscape.

At the same time, a land capability map was created (with six capability categories).

Whilst researching landscape changes in individual areas in the Republic of Croatia over a longer time period, authors have also made use, for example, of comparative analyses of various data sources. In research of environmental changes in a case study for the area of the central part of the Dalmatian hinterland from the middle of the 18th century to the present day,Fuerst-Bjeliš et al. (2011) used a combination of narrative, cadastral and cartographic sources – topographic and orthophoto maps, while a spatial analysis was conducted using GIS technology to research landscape changes in one area from the mid-18th century onwards.

This research, which began early in the 21st century (Fuerst-Bjeliš (2002),Fuerst-Bjeliš (2003),Fuerst-Bjeliš et al. (2003)), and was one of the first in modern times in Croatia to analyse changes in the landscape over a period of several centuries, making use of sources of different ages, including GIS technology and other research methods. More recent studies have followed, which including combined methods (along with GIS and other quantitative and qualitative methods) over shorter or longer time spans.Durbešić (2012) andDurbešić and Fuerst-Bjeliš (2016) conducted a spatial analysis of landscape changes in an area using GIS technology for a period from the 19

thcentury to today, using necessarily varied source categories and including an analysis of socio-geographical change factors.Blaće (2019) studied changes in forest cover in the case study of Ravni kotari, also for a period of greater time span, from the 19th century, to the present day using GIS technology and correlation methods. This research also included socio-geographical factors of change.

In this paper, based on the example of Central Lika, in addition to a spatial analysis of landscape patches for a specific point in time or condition (2012), we conducted a linear regression analysis with the aim of explaining the interrelations of the observed indicators (average index of patch shape, average index of core area, and average nearest neighbour index). Regression analysis has been applied till now in various research projects, but with other data and other indicators.Nupp and Swihart (2000) conducted an analysis of the influence of patch fragmentation in a woodland on different species of small mammals.

Analyses of the characteristics (for example, numbers, density and weight) of various species of small mammals in correlation with indicators of structural landscape patch variety, using logistical and multifaceted linear regression models have been carried out. For example,Pahernik (2000), andFaivre and Pahernik (2007), using the obtained values of spatial arrangement and density of sinkholes, performed a regression analysis to ascertain the correlation of characteristics (for example, density and numbers) of sinkholes and spatial features (for example, inclination, energy of the relief, azimuth, lie in relation to the points of the compass).

A more extensive analysis was conducted, which gave a better insight into these correlations with other physical and geographical features (for example, geological age, morphology and others), but without using socio-geographic variables.

Methodological Explanations

3.1. Methodological comments on the use of data on land cover/land use

When ascertaining landscape types, this paper uses an approach based on land cover/land use. For this purpose, data from the CORINE Land Cover 2012 (CLC 2012) database were used.

[1]

The CLC 2012 database was produced at the European level in the context of the

Copernicus Land Monitoring Service project.

The part of the database that relates to the Republic of Croatia was produced by the Croatian Agency for the Environment and Nature (HAOP).

The data in the database for the Republic of Croatia are arranged in a digital database according to the current administrative-territorial organisation of the country.

The standard approach to creating the CLC database is based on the visual interpretation of satellite imagery according to the accepted CLC methodology. Between 1985 and 1990, the European Commission implemented the CORINE programme, creating an information system on the condition of the European environment, while methodologies were developed and agreed upon at the European level.

Since the formation of the EEA (European Environment Agency) and the establishment of Eionet (European Environment Information and Observation Network), the coordination of the CORINE database, including updates, has been carried out by the European Environment Agency (CLC 2006 technical guidelines 2017).

Based on CLC methodology, data are created in a vector data model on a scale of 1:100 000, with a minimum polygon width of 100 metres for linear entities (lines) and 25 ha for surface entities (polygons). In addition to this data source and the method on which it is based, it is important to note that not all parts have been entered in the database.

For example, when looking at the landscape type

Built-up Land, smaller settlements are not visible because there is too low a concentration of objects in relation to grid resolution. Also, due to the insufficient width of objects in relation to the grid in the landscape type

Built-up Land, only highways are visible, while other roads are not.

In order to provide the most accurate definition of landscape types and landscape patches in Central Lika, data from the database were taken as factual and analysed as such in this paper.

The defined CLC nomenclature consists of 44 data classes. This means that at the European level, the diversity of land cover/land use is covered in 44 data classes (Cole et al. 2018).

From the CLC 2012 data base for Central Lika, 19 data classes were grouped into 6 landscape types for the purposes of this paper:

Built-up Land, Grassland, Agricultural Land, Forestland, Succession of Scrub/Forests, Water Areas.

However, as mentioned in the introduction, all the data in the database in question are actually parts of the landscape and those that refer to Central Lika are defined for the purposes of this paper as landscape patches in Central Lika.

Also, since all the data in the CLC 2012 are organised in data classes, those concerning the area of Central Lika are classed as landscape types in Central Lika.

[2]

This procedure resulted in landscape patches within a specified landscape type in Central Lika which were as homogeneous as possible, given their natural geographical features and the socio-geographical factors of landscape development which are visible in the space.

3.2 Methodological comments on spatial analysis methods used

An analysis was performed for this paper based on using various spatial analysis methods for landscape patches with the help of GIS technology. In doing so, the

shape, position and

condition of landscape patches were analysed in more detail, as was the landscape of Central Lika as a whole.

In order to calculate indices for landscape structure in this research, the basic software package ArcGIS Desktop version 10.0 produced by ESRI was used.

The

shape of landscape patches is determined by the

Mean Shape Index (herein after: MSI). MSI is based on the spatial analysis method known as

Shape Index, whose result is the application of a numerical shape index value (minimum, maximum and mean) for each of the observed sets.

In this paper, MSI measured the mean patch shapes for each landscape type and for the landscape patches of Central Lika as a whole.

For the vector shape data, MSI is calculated using the formula (Lang and Blaschke 2010):

where

p– circumference of patch,

a– surface area of patch

MSI refers to the deviation of the patch shape from a circle (Lang and Blaschke 2010). Thus, MSI measures the geometrical complexity of the patches – the greater the complexity, the greater the MSI value (Esbah 2009). Based on the patch complexity or MSI value, attributive descriptions are defined.

[3]

If the shape of the observed set of patches is simple, that is, close to a circle, the MSI value is close to one (1). On the other hand, the more complex a shape of observed patch sets, the greater the MSI value.

That means that elongated patches, corridors, spirals and other complex patch shapes have a higher MSI value than compact, rounded patches and patches with a simple shape.

The

Core Area Index (herein after: CAI) is used to determine landscape patch

condition. This is obtained by calculating the data from each patch in the observed set (for all landscape types and for the landscape of Central Lika as a whole). CAI is a numerical value which describes the ratio of the Core Area, herein after: CA) and the total area for each of the observed sets.

The smaller the numerical value of CAI, the greater the fragmentation of the inner areas, that is, they must be complex or elongated objects because the core area of the patches is smaller, and vice versa.

CA is obtained as the result of applying the GIS method for CA patches and is a numerical value (in this paper expressed in km

2) which refers to the total CA for each of the observed sets. In the technical sense, CA may be said to be equal to the inward depiction option of the spatial analysis method

Buffer.

The command-line syntax for

Buffer is (ESRI 2020):

<plaintext> Buffer_analysis <in_features> <out_feature_class> <buffer_distance_or_field> {FULL | LEFT | RIGHT | OUTSIDE_ONLY} {ROUND | FLAT} {NONE | ALL | LIST} {dissolve_field;dissolve_field...}

The CA of the patches in fact denotes the central patch area which is not exposed to external influences, that is, the patch area without the margins. It is important to note that the size of the patch margins (the influence of the exterior towards the core) depends on the object being studied. The issue concerns establishing effectively used areas depending on the context.

While researching small mammals in a woodland,Nupp and Swihart (2000) used a distance to the margin of 50 metres. While researching landscape patches for two different parts of the landscapeTúri (2010) used a distance to the margin of 10 metres.Lang and Blaschke (2010) used distances of 5m, 10m, 20m, 35m and 50m according to various examples.

For the purposes of this paper and the level of generalisation of the data used (100m), we used a distance of 50 metres for all landscape types and the landscape of Central Lika as a whole.

The

position of landscape patches was studied based on the GIS method of

Average Nearest Neighbour (Spatial Statistics), herein after:

Average Nearest Neighbour.

By determining the radius of distance by which the classification of intensity around every observed element can be determined (Pahernik 2000), this method was implemented in order to ascertain the average distance between each observed landscape patch and its nearest neighbour.

This also determined the grouping, randomness and dispersion of the observed landscape patches.

The near neighbour analysis using this method was conducted using vector data, taking into consideration all patches according to landscape type, and the landscape of Central Lika as a whole. On the other hand, in other research (for example,Faivre and Pahernik 2007, (Pahernik 2000, 2012), it was conducted using a raster data model which only looked at sinkholes.

One version of this method was chosen, according to which the landscape patches are turned into points or centroids in advance. The distance between the centroids of each patch and the location of the nearest neighbouring centroid is measured, then the average of all measured distances is calculated (ESRI 2019).

Average Nearest Neighbor is obtained by calculation based on formulas (ESRI 2020):

– observed mean distance between each feature and their nearest neighbor

– expected mean distance for the features given a random pattern

d

i

– equals the distance between feature i and

its nearest feature

n – total number of features

A– total study area

z

ANN

– z-score for

Average Nearest Neighbor

The results of applying this GIS method are the following values:

Observed Mean Distance,

[4]

Expected Mean Distance,

Nearest Neighbor Ratio,

z-value and

p-value.

[5]

If the value of the

Nearest Neighbor Ratio is less than one (1), this indicates grouping. If it is greater than one (1), it indicates the dispersion of the landscape patches.

Based on the obtained values, by using this spatial analysis method, attributive descriptions are automatically shown (grouped, random, dispersed), as listed and explained in this paper.

Research Area

The research area in this paper was Central Lika. According to current administrative-territorial organisation, Central Lika covers an area of three units of local self-government: the town of Gospić, the municipality of Lovinac and the municipality of Perušić which are integral constituents of Lika-Senj County. The total research area covers approximately 1,690 km

2.

There are 78 settlements located within the research area, 50 of which belong to the town of Gospić, 18 to the municipality of Perušić, and 10 to the municipality of Lovinac.

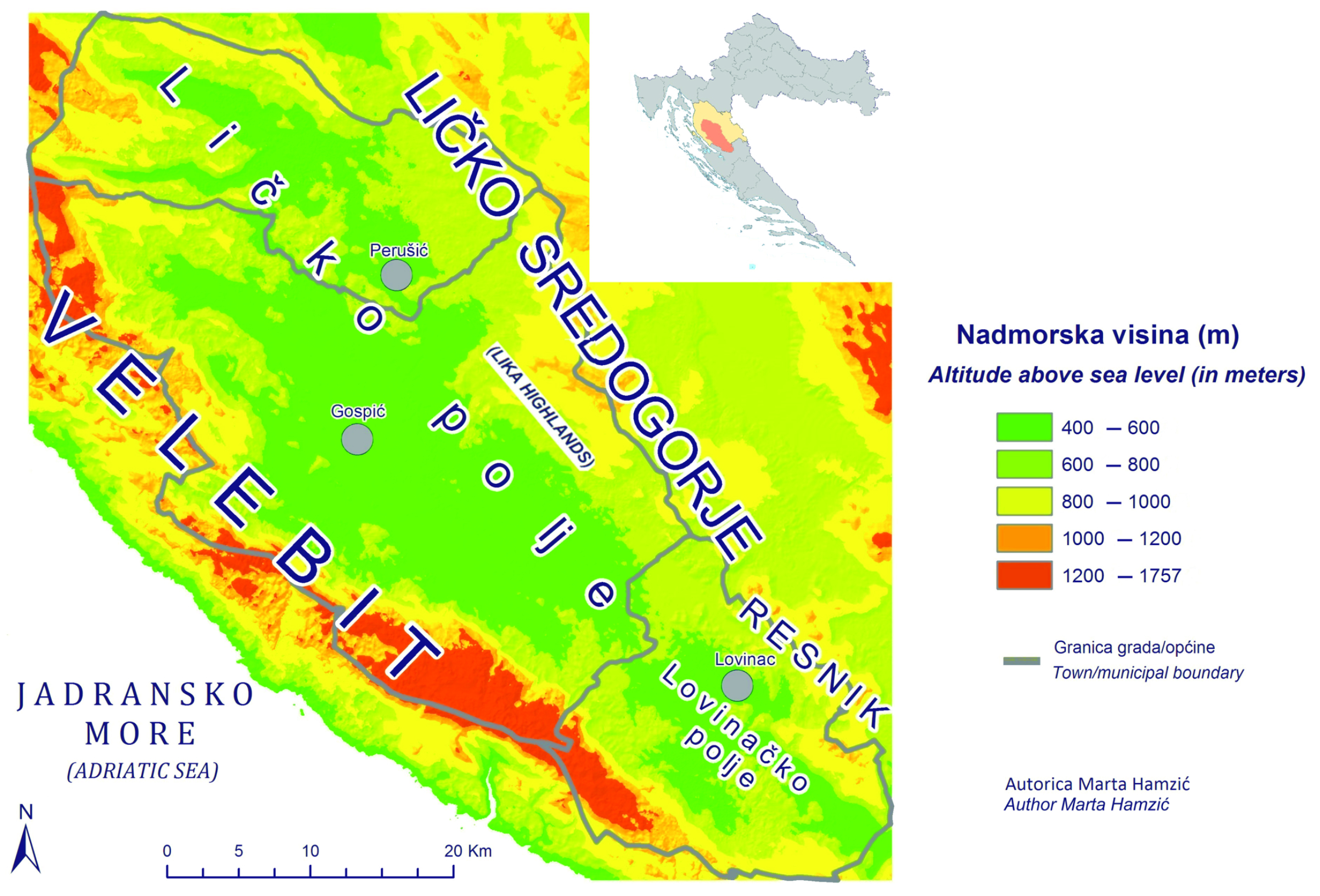

The basis for Central Lika's regional distinctness is an orographic framework comprising the mountainous ridge of Velebit to the west and southwest, the Lika highlands to the east, and the mountainous Resnik massif on the southeast side. The middle part of Central Lika is formed by Ličko polje, which is considered the largest karst field in the Republic of Croatia.

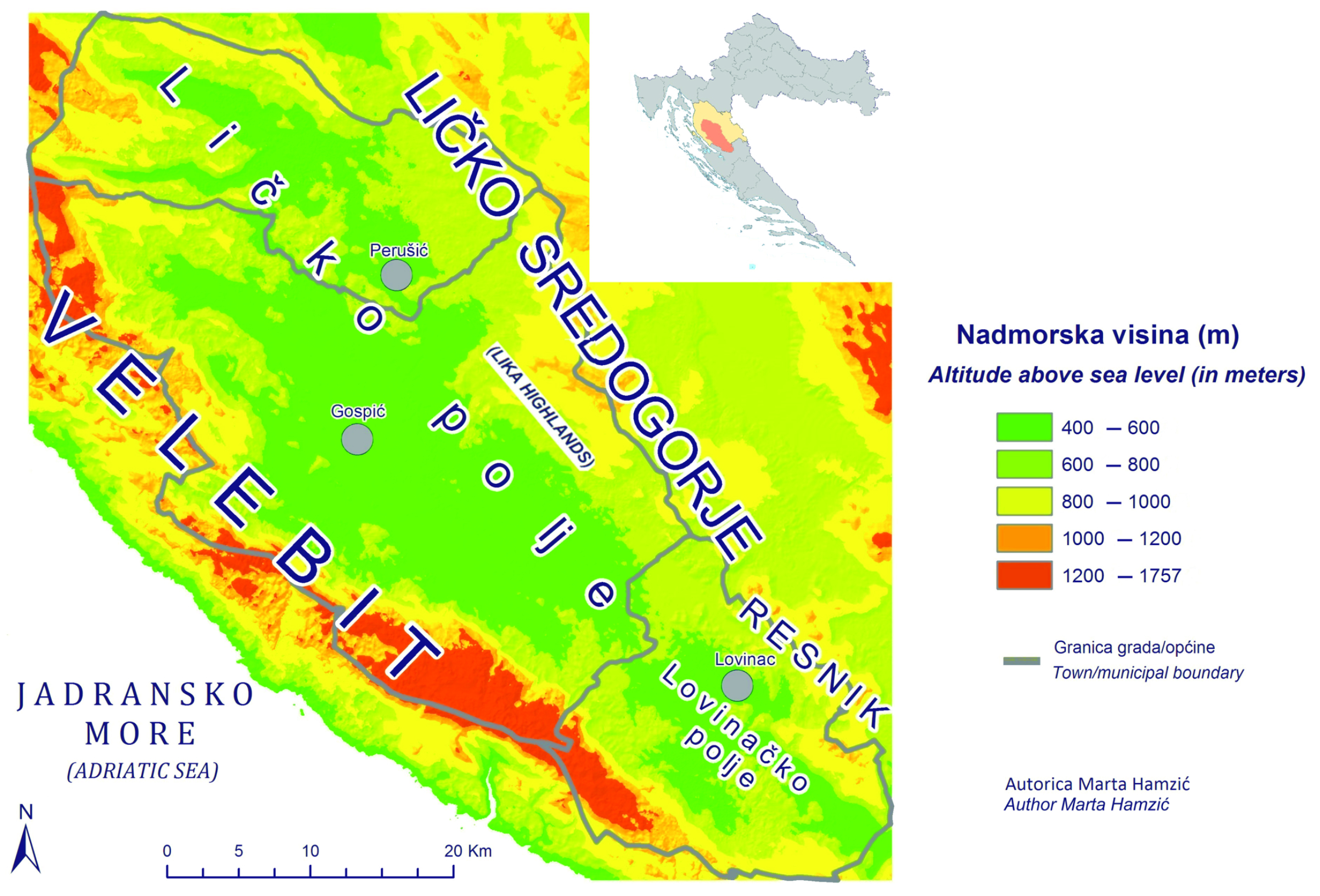

The southeast part of the research area is mostly occupied by Lovinačko polje. It is separated from the rest of Central Lika by conical hummocks, or elevations in the karst (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research area – Central Lika. Source: DARH, SGA; SRPJ, SGA

The range of altitudes above sea level in the research area is 461 m to 1,757 m, and the average altitude is 740 m (Pahernik and Jovanić, 2014).

The settlements and areas of human activity in Central Lika are mainly concentrated in the central area − Ličko polje (Lika Field).

The artificial surfaces and areas of human activity occupy a total of 17.05% of the surface area of Central Lika. The total artificial area is 1.29% and refers to the total area of human settlements

[6]

, which amounts to 0.66% of the area, while 0.63% of the area refers to transport facilities and economic-entrepreneurial activities (motorways and associated land, entrepreneurial zones, construction sites and mineral exploitation sites). Agricultural land covers a total of 15.76% of the area of Central Lika (CLC 2012).

Structural Characteristics of Landscape Patches in Central Lika According to Landscape Type

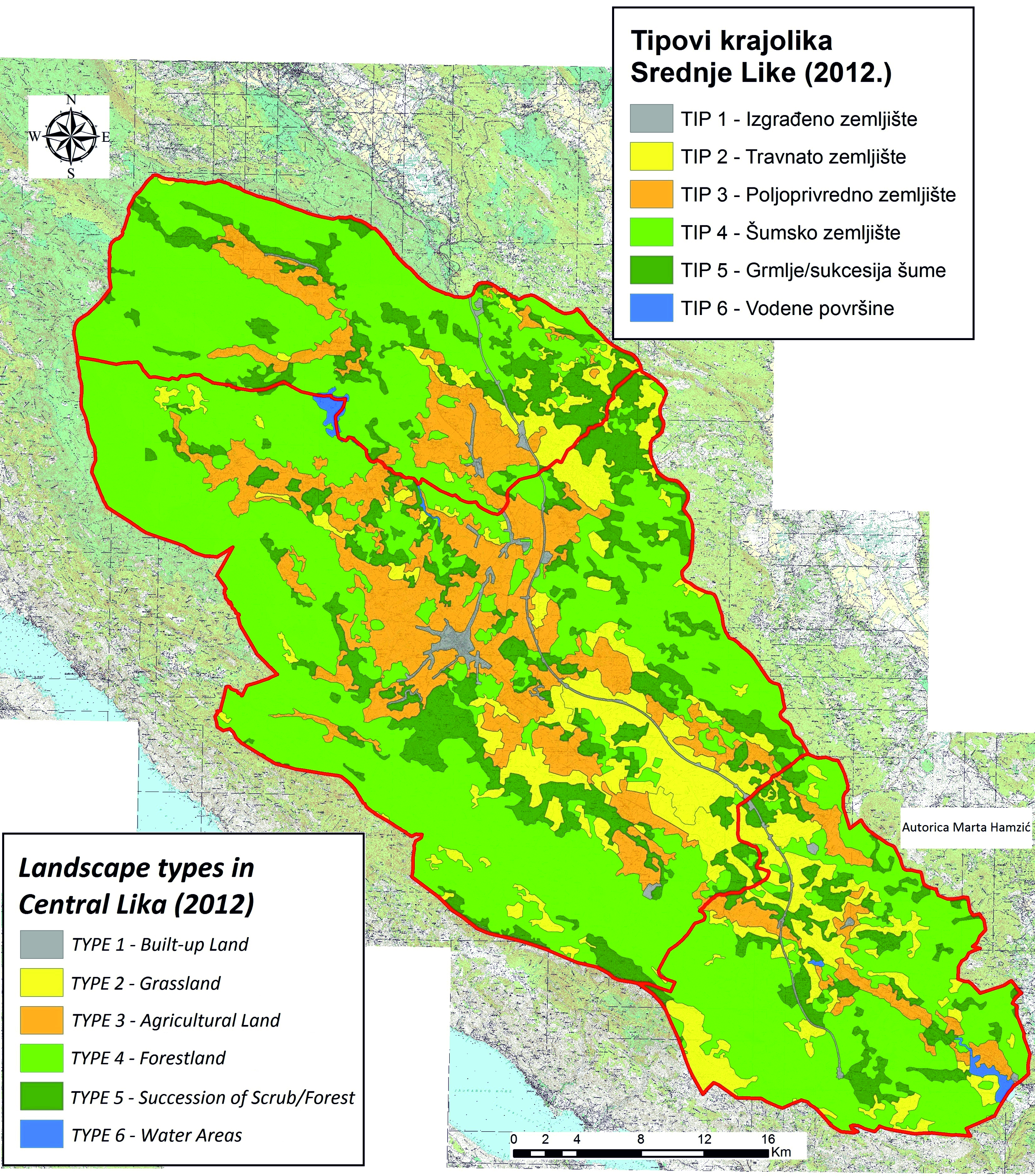

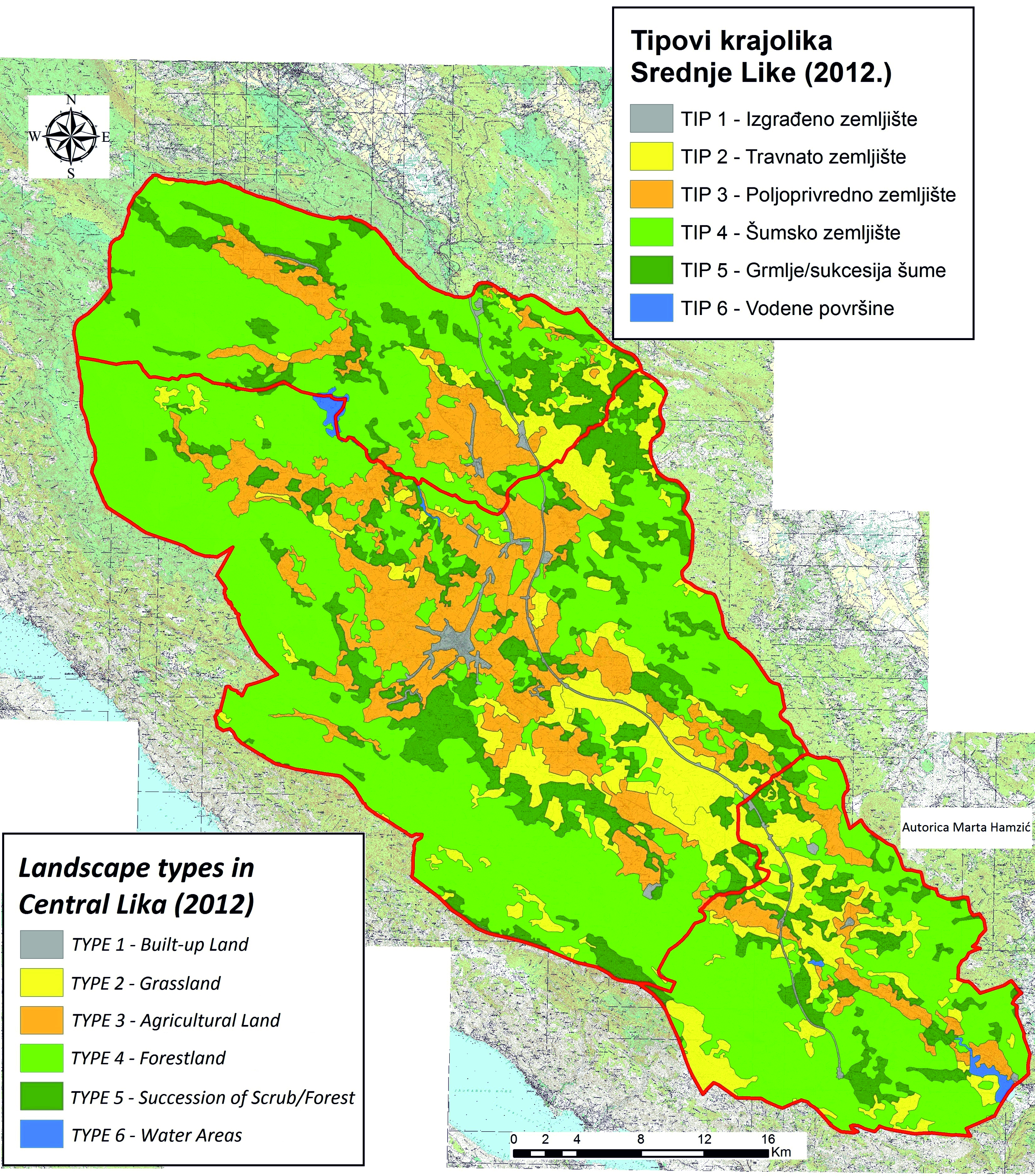

According to the procedure mentioned earlier in the paper, based on data on land cover/land use from 2012, the area of Central Lika is classified in six landscape types (Fig. 2):

Built-up Land

Grassland

Agricultural Land

Forestland

Succession of Scrub/Forests

Water Areas

Figure 2. Landscape types in Central Lika (2012). Source: CLC 2012, HAOP; SRPJ, SGA; Topographical maps, SGA

Based on several indicators and the use of spatial analysis methods, analyses were performed on patches of landscape types.

By applying them, values were obtained for the

shape,

position and

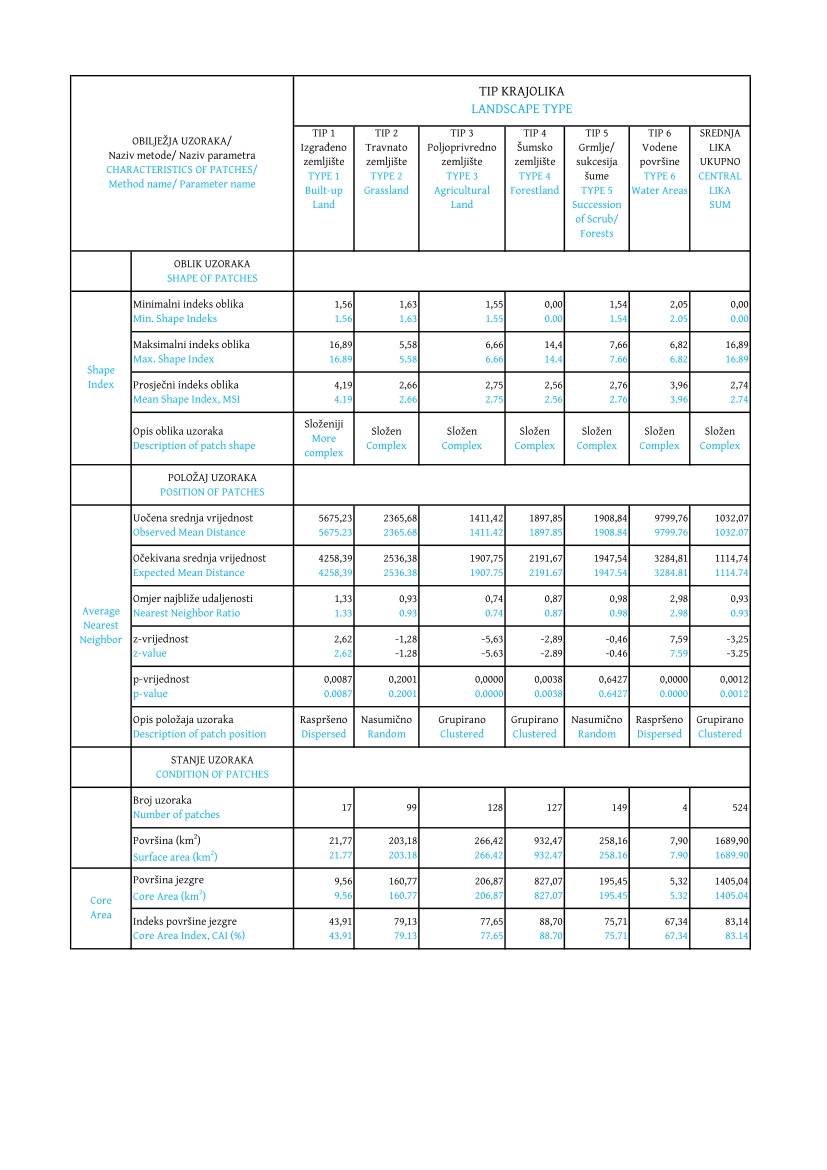

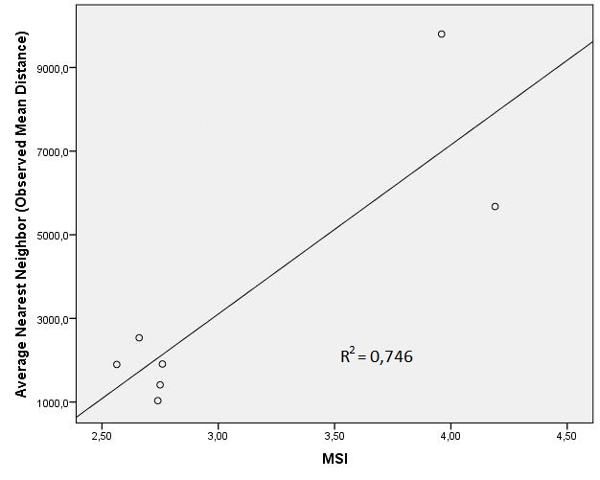

condition of patches of landscape types in Central Lika and the landscape of Central Lika as a whole. The obtained values are shown in Table 1.

Comments: In the section

Methodological comments on spatial analysis used the applied methods and meaning of attributive descriptions are explained in detail.

The landscape type

Built-up Landin the area of Central Lika comprises a total of 17 patches. This landscape type is mostly situated close to the central part. It includes settlements with a higher number of inhabitants, that is, settlements with a higher concentration of buildings, transport facilities and economic-entrepreneurial activities (motorways and associated land, entrepreneurial zones, construction sites and mineral exploitation sites).

The MSI value is highest compared to other landscape types (4.19). Given this value, the shape of the patches in this landscape type can be described as more complex. This is particularly pronounced in elongated patch examples such as the highway and its associated land. Among other landscape types in Central Lika, the category of

Built-up Land has the lowest CAI value (43.91%).

In this landscape type, the highest number of patches are complex or elongated, which is why the surface area of the core of the patches is the smallest. In terms of the position of the patches of this landscape type, they are dispersed. This means that in the area of Central Lika, for this landscape type, there is an averagely great distance between the centre of the patch and the centre of the nearest neighbouring patch.

The landscape type

Grassland in Central Lika comprises a total of 99 patches. In the area of Central Lika, this landscape type refers to pastures and natural grasslands which have developed as a result of the first phase of vegetation succession. After the end of the Second World War, "basic infrastructure was created and the initial industrialisation of the region was carried out" (Pejnović 1985: 66). More complex economic development was launched.

Thus, in accordance with socio-economic processes (deagrarisation, deruralisation, urbanisation, reduction of the total population and ageing of the population), the population of Central Lika has become less and less engaged in agriculture. Abandoning the land, or rather the extensification of agricultural land and neglect of cultivation, has led to a natural process of vegetation succession or natural afforestation (Fuerst-Bjeliš et al., 2000).

In the first phase of vegetation succession, low-growing plants take over agricultural land, forming grassland. In the second phase, medium-high vegetation develops on the grassland – shrubs and forest undergrowth. In the final, third phase, trees and forests thrive.

The landscape-type characteristics of

Grassland include a variety of grasses that do not grow tall, partly due to cattle grazing (pastures) and partly due to natural conditions (natural grasslands). Pastures are mostly located in areas away from settlements, because arable land is found next to settlements. Natural grasslands are located on mountain slopes, but also in the lowland areas (in Ličko polje on the west side of the highway).

The MSI value is one of the lowest among other landscape types (2.66), because in this type, the average shape of the patch is among the simplest, meaning it is closest to the shape of a circle. However, given this value, the shape of the patches in this landscape type can be described as complex. The CAI value is among the highest (79.13%) compared to other types of landscape in Central Lika.

This means that in this landscape type, the surface area of the core of the patches among the largest, because only a small number of patches have a complex or elongated shape. The patches in this landscape type are randomly positioned.

Hence, due to the average distance between the centres of neighbouring patches, they cannot be said to be either clustered or dispersed. However, the

p-value is 0.2001, which is higher than the borderline value (0.05), which means that these results do not differ from random ones and are therefore not analysed in the paper.

The landscape type

Agricultural Land comprises a total of 128 patches. They are located close to the central part of Central Lika, and are less represented on the margins. They are located next to settlements and have developed on more fertile soil.

The small population uses them for agricultural purposes, growing different crops, fruit, vegetables, cereals, fodder, and cattle-feed. If socio-economic processes continue in the area of Central Lika (deagrarisation, deruralisation, urbanisation, reduction of the total population, ageing of the population), it is likely that fewer and fewer areas will be used to cultivate labour-intensive crops (fruit and vegetables), and more areas will be used for non-labour-intensive crops (cereals, fodder and cattle-feed), or left fallow.

The landscape will be more neglected, but greener. Only in the area close to the town of Gospić is it possible to maintain the current extent of agricultural land.

The MSI value for the landscape type

Agricultural Land is 2.75. Given that this value is approximately equal to the MSI value for the Central Lika landscape as a whole (2.74), it can be said that the patch shape is approximately as complex as the average shape of all Central Lika patches. According to this value, the shape of the patches in this landscape type can be described as complex.

The CAI value is among the highest (77.65%), because the surface area of the patch core is larger, due to the large number of patches with a simpler shape and the small number of patches with a complex or elongated shape. The patches for the landscape type

Agricultural Land are in a clustered position. This means that in this landscape type, the average distance from the centre of one patch to the centre of the next neighbouring patch is not great.

In other words, the agricultural plots in Central Lika are arranged close together.

The landscape type

Forestland comprises a total of 127 patches. They are mainly located on the margins of the research area − on the slopes of Velebit, the Lika highlands and Resnik, and on the margins of Ličko polje (Lika field) and Lovinačko polje (Lovinac field). In Ličko polje, there are mostly deciduous forests of sessile oak with common hornbeam (

Querco petraeae-Carpinetum Illyricum) at lower altitudes.

Along the water courses, there are smaller areas beneath the forests of hydrophilic species of black alder with sedge (

Carici brizoidis-Alnetum), grey willow (

Salix cinerea) and willow (

Salix purpurea).

At higher altitudes above the mountain beech forests (

Fagetum illyricum montanum) in the area of central and northern Velebit, there are beech and fir forests (

Abieti-Fagetum illyricum), and in the highest parts of the mountain forests beneath the peaks, sub-alpine beech forests grow (

Fagetum illyricum subalpinum) (Pelcer and Martinović 2003).

The MSI value for this landscape type is the lowest (2.56) compared to other observed landscape types. Thus, the patches related to forest land are the simplest, that is, closest to the shape of a circle. Given this value, the shape of the patches can be described as complex. The CAI value for this landscape type is the highest (88.70%) compared to other types of landscape in Central Lika.

The core area of the patches is the largest, because the highest number of patches have a simpler shape. The patches in this landscape type are clustered, because on average there is a smaller distance between the centres of neighbouring patches.

The landscape type

Succession of Scrub/Forests is mainly located in Ličko polje and on the lowest slopes of the relief frame. Shrubs, that is, forest succession, are mostly located far from settlements, in the belt between grassland and deciduous forests. They are mostly created when agricultural land is abandoned or neglected, and represent the second phase of vegetation succession. This landscape type is characterised by different species of medium-high vegetation.

If these grow in areas where socio-economic processes have enriched the soil with mineral ingredients, they will gradually grow into forests. However, in some areas, due to the poorer quality of the depleted soil, the third phase of vegetation succession will not develop, and no tall vegetation (forests) will develop from the shrubs. On such substrates, heathers and ferns (

Genisto-Callunetum illyricum) develop as secondary vegetation (Pelcer and Martinović 2003).

The landscape type

Succession of Scrub/Forests comprises the highest number of patches − a total of 149. The MSI value for this landscape type is one of the highest (2.76), because the shapes of patches related to shrubs/forest succession is among the most complex compared to other observed landscape types. The CAI value is one of the lowest (75.71%), because the surface area of the patch core is one of the smallest due to fewer patches with a simpler shape, and more patches with a more complex shape.

Nevertheless, given the MSI value, the average patch shape for this landscape type is about as complex as the average patch in the Central Lika landscape (2.74). The patches in the landscape type

Succession of Scrub/Forests are positioned randomly. However, the

p -value is 0.6427 and is higher than the borderline value (0.05), which means that these results do not differ from random ones and are therefore not analysed in the paper.

The landscape type

Water Areas in Central Lika refers to several objects: one watercourse (the lower course of the River Lika, which also flows underground) and three bodies of water (Lake Kruščićko, Lake Štikada with Lake Ričice and the retainer on the subterranean River Obsenica). Even though, due to natural conditions, the area of Central Lika is abundant in water (numerous springs and sources, watercourses, and bodies of water), the data indicate that only a few objects belong to the landscape type

Water Areas which is understandable because they are very small in area.

Thus, this landscape type comprises the fewest patches −a total of four. The MSI value for this landscape type is one of the highest (3.96), and the average patch shape of this landscape type can be described as complex. The CAI value is one of the lowest (67.34%) compared to other observed landscape types, because the surface area of the patch core is one of the smallest due to the lower number of patches with simpler shapes and the higher number of patches with more complex shapes. Moreover, patches of landscape type

Water Areas, along with patches of landscape type

Built-up Area, have the most complex shapes.

The position of the patches of landscape type

Water Areas is dispersed. This means that on average, there is a long distance between the centres of neighbouring patches for this landscape type.

Regression Analysis of Selected Values of Structural Characteristics of Landscape Types in Central Lika

In the linear regression analysis, specific values were used for the characteristics of Central Lika´s landscape. These values were obtained as a result of using GIS technology methods on landscape patches in Central Lika according to landscape types and the Central Lika landscape as a whole. Based on the results of the linear regression analysis, the interrelations are explained further according to the applied indicators used in the study for the

shape,

position and

condition of the landscape patches in Central Lika.

Linear regression was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.

The model of simple linear regression is expressed using the following equation (Corporate Finance Institute 2020):

Y = a + bX + ϵ

Y – dependent variable

X – independent variable

a, b – parameters

ϵ − residual (error)

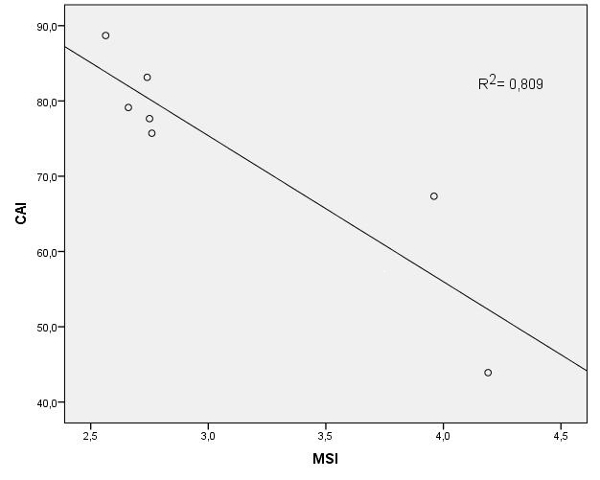

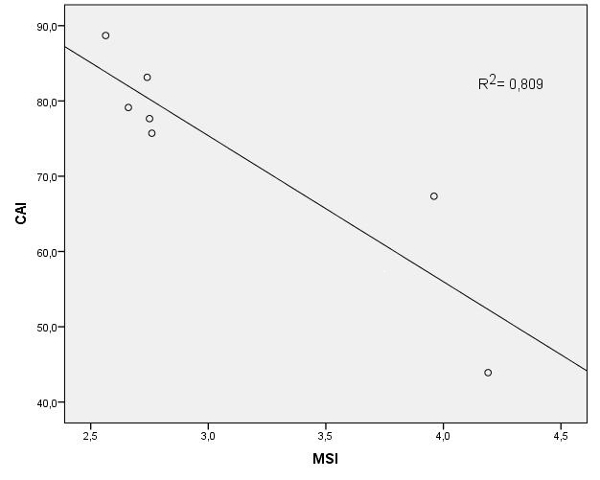

The relationship between the MSI indicator − the average value of the shape index (value for the

shape of landscape patches) and the CAI − core area index (value for the

condition of landscape patches) was analysed (Fig. 3).

Fig 3. Scatter diagram showing the correlation of the average value of the shape index (MSI) and the core area index (CAI)

By conducting a regression analysis of these indicators, the value of the standardized coefficient ß (ß = –0.899) was obtained, which indicated a strong negatively oriented connection.

A

p -value (

p = 0.006) was obtained, which indicated that the observed phenomenon differed from the random one.

This meant that as the shape index (MSI) increased, the core area decreased, and vice versa. Thus, it can be concluded that patches with more complex shapes have a smaller core area.

On the other hand, the simpler the shape of the patches (the closer to a circle), the larger the surface area of the core. This is also evident in the results presented in the previous chapter.

So, for example, the landscape type

Built-up Land has the highest MSI value and the lowest CAI value, because this landscape type has the largest number of patches with complex or elongated shapes, so the surface area of the patch core is the smallest.

On the other hand, the landscape type

Forestland has the lowest MSI value and the highest CAI value. This indicates that this landscape type has the highest number of patches with a simpler shape, which is why the surface area of the core of the patches is the largest.

The obtained value of the determination coefficient (R

2= 0.809) indicates that 80.9% of the connections were explained by the examined correlation.

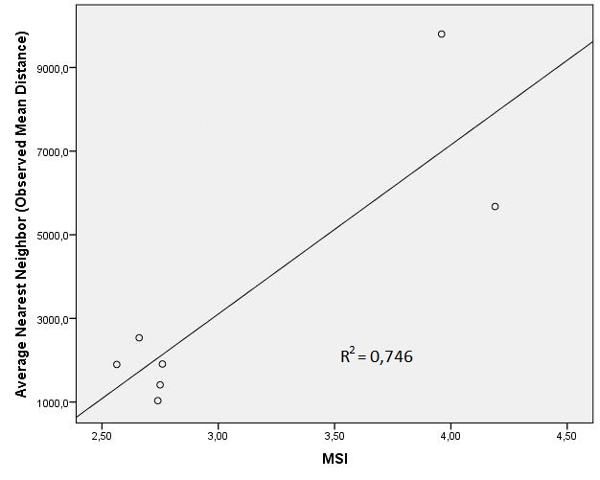

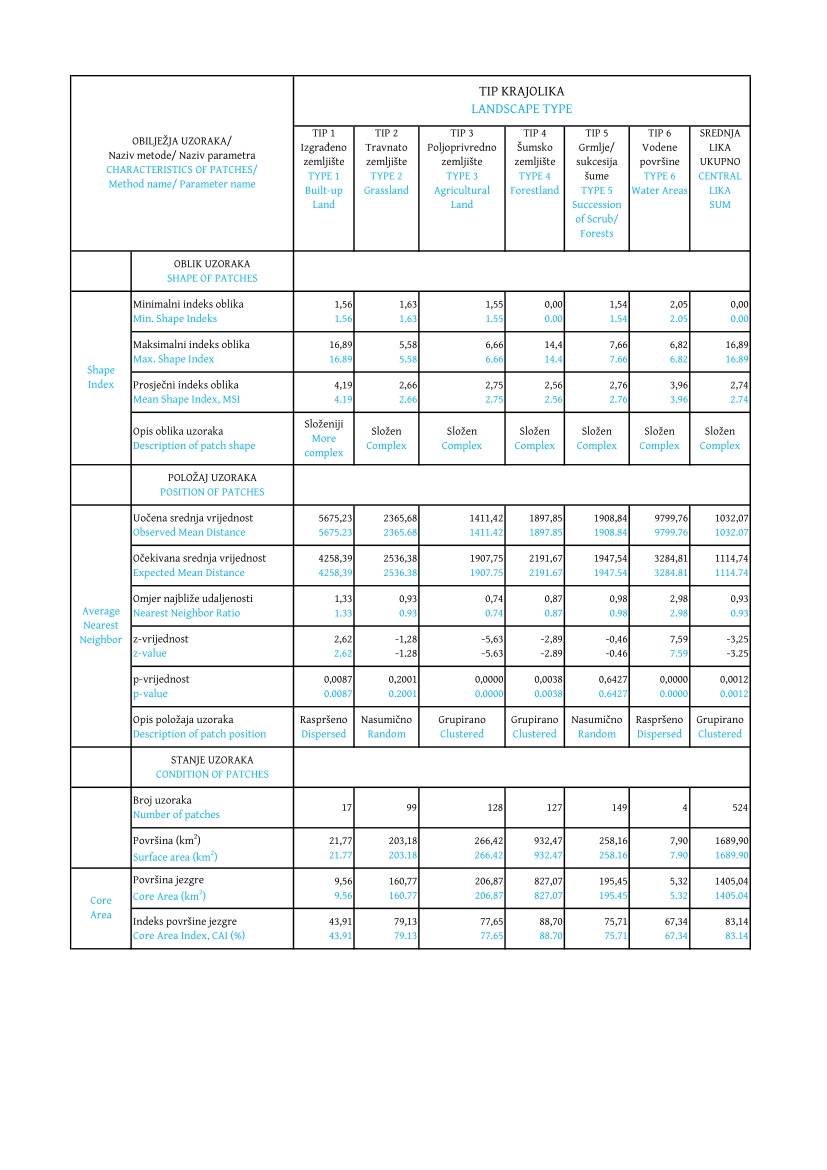

The relationship of the MSI indicator − the average value of the shape index (value for the

shape of landscape patches) and, using the GIS method

Average Nearest Neighbour, the values of the

Observed Mean Distance − the observed mean value of the average nearest neighbour (value for the

position of landscape patches) was analysed (Fig. 4).

Fig 4. Scatter diagram showing the correlation of the average value of the shape index (MSI) and the

Average Nearest Neighbour -

Observed Mean Distance)

The linear regression analysis yielded a value for the standardized coefficient ß (ß = 0.864) indicating a strong, positively oriented connection. A

p -value (

p = 0.001) was obtained which indicated that the observed phenomenon differed from the random one.

The result obtained meant that with an increase in the shape index, the adjacency of the patches increased, and vice versa. Thus, it can be concluded that patches of a more complex shape have a more distant near neighbour connection (they are more distant or dispersed), and the simpler their shape (more like a circle) the closer they are clustered.

For example, the landscape types

Built-up Land and

Water Area have the highest MSI indicator values, and also the

Average Nearest Neighbour -

Observed Mean Distance indicator values. In these landscape types, the largest number of patches have a complex or elongated shape.

Also, given the long distance from the patch centre to the centre of the neighbouring patch, the position of the patches is dispersed. On the other hand, the landscape type

Forestland has the lowest MSI indicator value, because it has the largest number of patches with a simpler shape. Given the small distance from the patch centre to the centre of the neighbouring patch, the patches are clustered.

The obtained determination coefficient (R

2 = 0.746) indicates that 74.6% of the connection was explained by the examined correlation.

Regression analysis was also used to analyse the connection of the CAI − core area index (value for the

condition of landscape patches) and the

Average Nearest Neighbour -

Observed Mean Distance (value for the

position of landscape patches).

The values of the determination coefficient (R

2 = 0.363) and the standardized coefficient ß (ß = –0.602) were obtained. However, the obtained

p -value (

p = 0.152) was higher than the borderline value (0.05), which meant that the observed phenomenon did not differ from the random one, so these results were not analysed further.

Previously conducted research byM. Jovanić (2017) on a more detailed sample, landscape patches for both subtypes and types of landscapes and the landscape of Central Lika as a whole, confirmed the results presented here for the correlation between

shape and

condition (ß = − 0.550;

p = 0.004; R

2 = 0.302) as well as

shape and

position (ß = 0.659;

p = 0.001; R

2 = 0.434) of the Central Lika landscape patches, while also no correlation for the

condition and

position of the landscape patches of Central Lika was found.

Conclusion

The research presented relates to the application of spatial and linear regression analysis in determining the structural features (

shape,

positionand

condition) of patches in the Central Lika landscape, that is, their interrelation at one particular point in time (2012).

The spatial analysis in this paper uses an approach in which a set of indicators for landscape structure and GIS technologies was applied to landscape types and the Central Lika landscape, using a single spatial analysis method for each of the structural characteristics. To determine the landscape types, an approach based on land cover/land use was used.

Six landscape types were identified in Central Lika and are analysed in detail in this paper.

Linear regression analysis established the connection between the

shapeand

condition, and the

shapeand

position of the patches in the landscape of Central Lika. However, no correlation was found for the

condition and

position of the patches in the Central Lika landscape.

Thus, for

shape and

condition, the results showed that patches with a more complex shape had a smaller core area, that is, the simpler the shape of the patches (closer to a circle), the larger the surface area of the core.

This was also evident in the results, where the landscape types

Built-up Land and

Forestland stood out.

In fact, considering

shape, the results showed that in Central Lika, patches of the landscape type

Forestland had the simplest shape, that is, were closest to a circle, while landscape type patches of

Built-up Land had the most complex shape,

because this landscape type consists of patches with a complex shape (for example, settlements) or an elongated one (for example, highways and associated land). On the other hand, considering the

condition of landscape patches, the results showed that in the landscape type

Forestland the patch core area was the largest because,

compared to other landscape types, a large number of patches had a simpler shape, while in the landscape type

Built-up Land, the patch core area was the smallest because it had the largest number of patches with a complex or elongated shape. Based on the above, that is, the established link between

shape and

condition,

it can be concluded that the patches of the landscape type

Forestland are the least exposed to external influences, because they occupy the fewest marginal areas. On the other hand, patches in the

Built-up Land landscape type occupy the most marginal areas and are exposed to the greatest external influences.

The results of the linear regression analysis for the

shape and

position of patches in the Central Lika landscape showed that patches with a more complex shape have a higher level of adjacency, and the simpler their shape (closer to a circle) the lower the adjacency. This is also evident in the results presented in the paper.

Observing the landscape types that have the most complex patch shapes,

Built-up Land and

Water Areas, they also have the highest adjacency. Only these landscape types were found to have dispersed patches, that is, the average distance from the centre of the patch to the centre of the neighbouring patch is long.

On the other hand, the landscape type

Forestland that has the simplest shape of landscape patches and the lowest adjacency of all the landscape types in Central Lika. Also, this landscape type was found to have clustered patches, that is, the average distance from the centre of one patch to the centre of its neighbour was not long.

Data from the CORINE Land Cover 2012 database were used in this paper. It does not record all landscape categories, which is a certain disadvantage of this database. However, on the other hand, its significant advantage is that it is made at the European level according to the accepted CLC methodology, so this research is completely comparable with other research in Europe that would use the approaches and methods presented in this paper.

The comparability of the results in the case of using some other databases, such as multispectral satellite images, would be significantly reduced due to the large differences in approaches and processing methodologies among different authors.

The applicability of knowledge about the interrelationships of shapes, positions and conditions of landscape patches, which indicate the (non) presence of external influences on its development and changes, is primarily in the physical planning of various activities and areas / facilities of appropriate purposes.

In particular, the interrelationships of the shape and position of landscape samples can provide insight into the most suitable site selection for protective environmental activities, for example in activities related to the protection of humans, plants and animals from negative external influences (locating noise barriers, nests, watering places, etc.).

Uvod

Prirodni se krajolik može definirati prirodnim čimbenicima: klimom, tlom, vodom, reljefom, geološkom osnovom, florom i faunom (Herlitzius i dr. 2009). On je konstantno izložen promjenama uzrokovanim kako prirodnim silama tako i društveno-gospodarskim aktivnostima. Promjenom makar samo jednog od prirodnih čimbenika čovjekovom djelatnošću, načinom života/ kulturom pojedinih društvenih grupa, prirodni krajolik postaje kulturni. Stoga se može reći kako su danas gotovo svi krajolici na Zemlji zapravo kulturni, a razvoj krajolika odnosno njegove promjene su „izraz dinamične interakcije prirodnih i kulturnih utjecaja“ (Antrop 2005:22). Posljedice te interakcije vidljive su i u jakoj povezanosti mozaika uzoraka krajolika i ekoloških procesa (Fu i dr. 2006) te antropogenog djelovanja. Naime, procesi koji se odvijaju u krajoliku stvaraju uzorke i strukture, no istodobno ih vode i usmjeruju prostorne strukture koje prevladavaju. Ukratko, riječ je o uzrocima i posljedicama prostornoga heterogeniteta za različite ekološke procese (Lang i Blaschke 2010).

Struktura krajolika je specifičan spoj dijelova, tj. uzoraka krajolika. Obilježja strukture krajolika kao prostorne komponente mogu se jasno promatrati, opisivati i kvantificirati (Blaschke 2000). Razlog tome su i računalni alati, metode geografske obrade informacije, kao i obrada digitalnih slika koji su imali velik utjecaj u proučavanju strukture, odnosno razvoja krajolika (Lang i Blaschke 2010).

Pri utvrđivanju tipova krajolika postoje dva pristupa: na temelju zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta i na temelju sinteze prirodnih i kulturnih obilježja korištenjem hijerarhijskog pristupa (Dumbović Bilušić 2015). Kao rezultat toga se, s obzirom na promatrana obilježja, utvrđuju što homogeniji prostorni dijelovi krajolika koji se svrstavaju u tipove krajolika.

Cilj ovog rada je, korištenjem odgovarajućih metoda prostorne analize, utvrditi pojedina strukturna obilježja (

oblik),

položaj i

stanje uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like prema tipovima krajolika za 2012. godinu te regresijskom analizom ustanoviti postoji li povezanost među njima.

Pri utvrđivanju tipova krajolika Srednje Like korišten je pristup koji se temelji na zemljišnom pokrovu/načinu korištenja zemljišta. Naime, korišteni su podatci iz baze podataka CORINE Land Cover iz 2012. godine (CLC 2012). Ti podatci ukazuju na prirodno-geografska obilježja i društveno-geografske čimbenike razvoja krajolika koji su vidljivi u prostoru i time su u radu razmatrani kao zemljišni pokrov/način korištenja zemljišta Srednje Like.

Baza podataka (CLC 2012) sastoji se od digitalnih podataka koji se zapravo odnose na dijelove krajolika (npr. naselje, pašnjak, jezero i sl.), a raspoređeni su u klase podataka. U ovom radu su svi ti digitalni podatci koji se odnose na područje Srednje Like definirani kao uzorci krajolika Srednje Like. Za potrebe ovog rada sve su klase podataka koje se odnose na područje Srednje Like raspoređene u jedan od tipova krajolika (npr. klase podataka

Pašnjaci i

Prirodni travnjaci svrstane su u tip krajolika

Travnato zemljište). Na temelju prethodnog može se reći kako su u ovom radu svi uzorci krajolika Srednje Like svrstani u jedan od tipova krajolika Srednje Like. Pri tome se uzorke krajolika težilo rasporediti u pojedini tip krajolika tako da međusobno budu što homogeniji s obzirom na njihova prirodno-geografska obilježja i društveno-geografske čimbenike razvoja krajolika koji su vidljivi u prostoru.

Svi uzorci i tipovi krajolika Srednje Like korišteni u ovom radu su podatci u digitalnom obliku te je najpogodnijim načinom provedena prostorna analiza – upotrebom GIS-a. Naime, GIS tehnologija omogućava kvalitetne i točnije informacije o krajoliku i njegovim obilježjima (Olahová i dr. 2013) te veću brzinu i čitav niz dodatnih kvalitativnih i kvantitativnih analiza koje bi bez primjene GIS-a bile vrlo teško, odnosno nezamislivo provesti. Također, analize pokazatelja krajolika predstavljaju temelj za usporedbu različitih scenarija u krajoliku i za razumijevanje pojedinih obilježja krajolika tijekom vremena time (Paudel i Yuan 2012).

Dosadašnja istraživanja

Krajolici, odnosno pojedini dijelovi krajolika se, koristeći različite pristupe i metode, istražuju u domaćim i inozemnim radovima s različitih aspekata, analizirajući kako strukturu tako i funkciju krajolika, odnosno kroz jedno vremensko razdoblje ili više njih.

Pri istraživanju krajolika proučavaju se uzorci ili dijelovi krajolika. U radovima se prikazuju jedna ili više razina krajolika (npr. podtip, tip, krajolik u cjelini), dok se analize provode najčešće na jednoj studiji-slučaju, odnosno za jedno izdvojeno područje ili pak usporedno na više studija-slučaja, odnosno za više različitih područja.

Lang i Blaschke (2010) primjenjujući GIS tehnologiju analizirali su sva tri navedena aspekta krajolika (struktura, funkcija i razvoj) na različitim primjerima, odnosno krajolicima primjenjujući naizmjence deskriptivno-analitičku i empirijsku metodu. Međutim, u ovom radu se, pri analizi strukturnih obilježja uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like, za svako od promatranih strukturnih obilježja koristi samo jedna odgovarajuća metoda prostorne analize (

Shape Index za

oblik,

Average Nearest Neighbor za

položaj i

Core Area za stanje).M. Jovanić (2017) također je analizirala sva tri navedena aspekta krajolika jedne studije-slučaja, područja Srednje Like. Pri tome je korištenjem metoda prostorne analize i regresijske analize analizirala obilježja i razvoj obilježja uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like za podtipove i tipove krajolika te krajolik u cjelini. U pojedinim radovima drugih autora (npr.Rutledge 2003,Olahová i dr. 2013) uz navedene metode prostorne analize koristi se i veći broj drugih. Tako jeRutledge (2003) prikazao model s većim brojem pokazatelja koji se mogu primijeniti pri analizi fragmentacije uzoraka krajolika, ali pri tome ne provodi i analizu na određenom konkretnom prostoru.

Upotrebom podataka za jednu vremensku točku, u pojedinim se radovima istražuje trenutačna, suvremena struktura krajolika.Túri (2010) proveo je analizu strukture krajolika na razini uzorka. Pri tome je metodama prostorne analize za dva područja usporedio rezultate čak 30 pokazatelja.Blaće (2015) analizirao je razvoj strukture krajolika općine Nadin korištenjem više od 20 pokazatelja. Međutim, u ovom radu za svako strukturno obilježje se radi preglednosti primijenjuje jedna odgovarajuća metoda prostorne analize te se navode primjereni atributni opisi kako bi se pobliže objasnili rezultati.Blaschke (2000) analizu strukture krajolika proveo je na većem broju primjera empirijskom metodom pri istraživanju prostorno-statističkih metoda GIS tehnologije u smjeru povezanosti i optimizacije prostornog rasporeda elemenata krajolika. Međutim, korištenjem podataka za jednu vremensku točku u radovima se analiziraju i njihove strukturne promjene tijekom vremena, tako su primjericeAničić i Perica (2003) korištenjem fotografskog sadržaja krških poljoprivrednih područja u jednoj vremenskoj točki analizirali njihove strukturne promjene tijekom vremena.

Korištenjem podataka za više vremenskih točaka, u pojedinim radovima se analizira promjena, odnosno razvoj krajolika za jedno vremensko razdoblje ili više njih.Esbah (2009) analizirao je promjenu strukturnih obilježja uzoraka gradskog područja Aydin u Turskoj za dvije promatrane godine (1977. i 2002.) upotrebom većeg broja pokazatelja, odnosno metoda prostorne analize, no ne uključuje primjerice pri tome i metode

Average Nearest Neighbori

Core Area, korištene u ovom radu. U raduCole et dr. (2018) za više vremenskih razdoblja (2000−2006, 2006−2012) provedena je analiza promjene zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta na studiji-slučaju za područje Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva, utvrđenih na temelju podataka baze CORINE Land Cover, no pri tome se ne analiziraju i strukturna obilježja.Paudel i Yuan (2012) (2012) iznose istraživanje o razvoju krajolika te ekološke posljedice izgradnje metropolitanskog područja Saint Paula i Minneapolisa u Sjedinjenim Američkim Državama za više godina (1975, 1986, 1998. i 2006.), a pri analizi koriste različite vrste podataka (aerosnimke, ortofoto i multispektralne satelitske snimke te prostorno-planske dokumente). Hrvatski autori u istraživanjima krajolika kroz više vremenskih točki analiziraju različite objekte upotrebom različitih vrsta podataka i metoda analize.Morić-Španić i Fuerst-Bjeliš (2017) utvrdili su tipove krajolika na studiji-slučaju za područje otoka Hvara na temelju kombinacije više vrsta podataka za dvije različite godine. Koristeći vegetacijske karte (1975) i CORINE Land Cover, podatke Hrvatskih šuma i digitalnih ortofotosnimaka (2011) utvrdili su trendove promjene krajolika. U radu je primjenjen GIS model koji ima moguću aplikaciju kroz model revitalizacije poljoprivrede.Cvitanović (2014) je za razdoblje 1991−2011 primjenom daljinskih istraživanja također proveo analizu promjene zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta na studiji-slučaju za područje Hrvatskog zagorja. Za isto područje i vremensko razdobljeCvitanović i Fuerst-Bjeliš (2018) analizirali su promjene zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta pri čemu su u metodologiju istraživanja uključena daljinska istraživanja, GIS, regresijska analiza i kvalitativne metode s ciljem analize društveno-geografskih čimbenika promjene.Jogun i dr. (2017 i 2019) su upotrebom, između ostalog, metoda daljinskih istraživanja i simulacijskog modela za analizu i projekciju promjena zemljišnog pokrova, analizirali promjene zemljišnog pokrova u sjevernoj Hrvatskoj za razdoblje 1981−2011 i Požeško-slavonskoj županiji za razdoblje 1985−2013.

Posebno je potrebno izdvojiti radove u kojima se analiziraju podatci vremenskog raspona od 250 godina i više, što je vrijeme za koje nisu dostupne satelitske snimke koje bi se analizirale metodama daljinskih istraživanja, već se nužno koriste različiti tipovi izvora iz različitih vremenskih razdoblja, što zahtijeva sasvim specifičnu metodologiju rada. U tim istraživanjima koriste se i recentni podatci te se time dobiva dobiva veliki vremenski raspon istraživanja.Olahová i dr. (2013) su za razdoblje od 250 godina kartografski utvrdili promjene zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta na studiji-slučaju za područje klizišta Handlová u Slovačkoj. Za dvije recentnije godine (2003. i 2011.) analizirali su promjenu strukturnih obilježja uzoraka tog područja korištenjem većeg broja pokazatelja. U prvom dijelu radaFuerst-Bjeliš i dr. (2000) deskriptivno-analitičkom metodom izneseni su rezultati istraživanja antropogenog utjecaja na okoliš središnjeg Velebita kroz duže vremensko razdoblje (od prije 17. stoljeća). Pri tome je napravljena dijakronijska analiza i model periodizacije promjena jer se uspoređuju pojedini pokazatelji različitih faza promatranog razdoblja i analizira se njihov razvoj. U drugom dijelu rada, na temelju uspostave sintetičkog kriterija koji se sastoji od tri geoekološka parametra (relativna visina, dužina padina, indeks dužine i relativne visine) i jednog estetskog parametra (otvorenost pogleda), korištenjem multivarijantne cluster i diskriminantne analize, provedena je geoekološka evaluacija krajolika. Pri tome je konstruirana bonitetna karta (šest bonitetnih kategorija). Pri istraživanju promjena krajolika pojedinih područja Republike Hrvatske kroz duži vremenski period u radovima se koristi, na primjer, komparativna analiza različitih izvora podataka. U istraživanju promjena okoliša na studiji slučaja za područje središnjeg dijela Dalmatinske zagore od sredine 18. stoljeća do danas,Fuerst-Bjeliš i dr. (2011)su primjenili kombinaciju narativnih, katastarskih i kartografskih izvora − topografske i ortofotokarte, a prostorna analiza je provedena primjenom GIS-a. To je istraživanje, započeto početkom 21. stoljeća (Fuerst-Bjeliš (2002),Fuerst-Bjeliš (2003),Fuerst-Bjeliš i dr. (2003)), jedno od prvih u novijem razdoblju u Hrvatskoj u kojem se analiziraju promjene pejzaža za razdoblje od nekoliko stoljeća, koje koristeći izvore različite starosti uključuju GIS i ostale metode istraživanja. Na to se istraživanje nadovezuju i kasnija, recentnija istraživanja koja uključuju kombinirane metode (uz GIS i druge kvantitativne i kvalitativne metode) u kraćem ili duljem vremenskom rasponu. U radovimaDurbešić (2012) teDurbešić i Fuerst-Bjeliš (2016) provedena je prostorna analiza promjena pejzaža također jedne izdvojene studije-slučaja u Dalmatinskoj zagori. Za područje planine Svilaje, za razdoblje od 19. stoljeća do suvremenog razdoblja, korištene su pri tome nužno različite kategorije izvora uz primjenu GIS-a. To je istraživanje također uključilo i analizu društveno-geografskih čimbenika promjene.Blaće (2019) istražio je promjene šumskog pokrova na studiji-slučaju Ravnih kotara, također za razdoblje većeg vremenskog raspona, od 19. stoljeća, do danas uz primjenu GIS-a i metode korelacije. I to je istraživanje uključilo društveno-geografske čimbenike promjene.

U ovom je radu na primjeru područja Srednje Like, osim prostorne analize uzoraka krajolika za jednu određenu vremensku točku odnosno stanje (2012.), provedena i linearno-regresijska analiza s ciljem objašnjenja međuodnosa promatranih pokazatelja (prosječnog indeksa oblika uzorka i prosječnog indeksa površine jezgre, odnosno prosječnog indeksa susjednosti). Regresijska analiza korištena je do sada u pojedinim radovima, ali s drugim podatcima i drugim pokazateljima. Tako suNupp i Swihart (2000) proveli analizu utjecaja fragmentacije uzoraka šumskog zemljišta na obilježja različitih vrsta malih sisavaca. Provedene su analize obilježja (npr. prisutnost, gustoća i težina) različitih vrsta malih sisavaca u međuzavisnosti s pokazateljima strukturnih različitosti uzoraka krajolika, pri čemu su korišteni logistički i višestruki linearni regresijski modeli. Primjerice, u radovimaPahernik (2000) teFaivre i Pahernik (2007) s dobivenim vrijednostima prostornog rasporeda i gustoće ponikava, primijenjena je regresijska analiza s ciljem utvrđivanja međuzavisnosti obilježja (npr. gustoća, broj) ponikava i obilježja prostora (npr. nagib, energija reljefa, azimut, pružanje prema stranama svijeta). Također je provedena je i daljnja analiza pri kojoj su produbljeni ti odnosi s drugim fizičko-geografskim obilježjima (npr. geološka starost, morfologija i dr.), no bez društveno-geografskih varijabli.

Metodološka objašnjenja

3.

3.1. Metodološke napomene vezane uz upotrebu podataka zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta

U ovom radu je pri utvrđivanju tipova krajolika korišten pristup koji je temeljen na zemljišnom pokrovu/načinu korištenja zemljišta. U tu svrhu korišteni su podatci koji su sadržani u bazi podataka CORINE Land Cover 2012 (CLC 2012).

[1] Baza podataka CLC 2012 izrađuje se na europskoj razini u okviru projekta

Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Dio te baze koji se odnosi na Republiku Hrvatsku proizvod je Hrvatske agencije za okoliš i prirodu (HAOP). Podatci za Republiku Hrvatsku u toj bazi organizirani su u digitalnu bazu podataka prema važećem administrativno-teritorijalnom ustroju.

Standardni pristup izrade baze podataka CLC temelji se na vizualnoj interpretaciji satelitskih snimaka prema prihvaćenoj CLC metodologiji. Naime, u razdoblju 1985.–1990. Europska komisija je primijenila program CORINE te je nastao informacijski sustav o stanju europskog okoliša, a metodologije su razvijene i dogovorene na razini EU-a. Nakon uspostave Europske agencije za okoliš (EEA) te osnivanja Europske informacijske i promatračke mreže za okoliš (Eionet), koordinaciju baza podataka CORINE, uključujući i ažuriranja, provodi Europska agencija za okoliš (CLC 2006 technical guidelines 2017).

Na temelju CLC metodologije stvaraju se podatci u vektorskom modelu podataka u mjerilu 1:100 000, minimalne širine 100 metara za linearne entitete (linije) i 25 ha za površinske entitete (poligone). Uz navedeni izvor podataka, odnosno metodu na kojoj se temelji, važno je napomenuti kako u bazu podataka nisu uneseni svi dijelovi. Tako, na primjer, kod tipa krajolika

Izgrađeno zemljište zbog nezadovoljavanja kriterija dovoljne koncentracije objekata u odnosu na rezoluciju rešetke, nisu vidljiva manja naselja. Također, kod tipa krajolika

Izgrađeno zemljište zbog nedovoljne širine objekta u odnosu na rešetku, od prometnica je vidljiva samo autocesta, dok ostale nisu vidljive. U namjeri što vjernijeg definiranja tipova krajolika i uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like, podatci navedene baze su korišteni kao činjenični te su kao takvi analizirani u radu.

Definirana CLC nomenklatura sadrži ukupno 44 klase podataka. To znači da je na europskoj razini raznolikost zemljišnog pokrova/načina korištenja zemljišta generalizirana na 44 klase podataka (Cole i dr. 2018).

Unutar baze podataka CLC 2012 za područje Srednje Like evidentirano je 19 klasa podataka koje su za potrebe ovog rada svrstane u šest tipova krajolika:

Izgrađeno zemljište ,Travnato zemljište, Poljoprivredno zemljište, Šumsko zemljište, Grmlje i sukcesija šume, Vodene površine. Naime, kako je u Uvodu ovog rada navedeno, svi podatci u toj bazi podataka su zapravo dijelovi krajolika, a oni koji se odnose na područje Srednje Like su za potrebe ovog rada definirani kao uzorci krajolika Srednje Like. Također, s obzirom na to da su svi podatci u bazi podataka CLC 2012 raspoređeni u klase podataka, one koje se odnose na područje Srednje Like su za potrebe ovog rada svrstane u tipove krajolika Srednje Like.

[2] Provedeni postupak rezultirao je time da su uzorci krajolika unutar pojedinog tipa krajolika Srednje Like što homogeniji s obzirom na njihova prirodno-geografska obilježja i društveno-geografske čimbenike razvoja krajolika koji su vidljivi u prostoru.

3.2. Metodološke napomene vezane uz korištene metode prostorne analize

U radu je provedena analiza koja se temelji na korištenju različitih metoda prostorne analize na uzorcima krajolika pomoću GIS tehnologije. Pri tome se detaljnije analiziraju

oblik,

položaj i

stanje uzoraka krajolika za tipove krajolika te za krajolik Srednje Like u cjelini. U radu je za izračunavanje pokazatelja za strukturu krajolika korišten osnovni softverski programski paket ArcGIS Desktop verzije 10.0 proizvođača ESRI.

Oblik uzoraka krajolika ustanovljen je na temelju prosječne vrijednosti indeksa oblika (engl.

Mean Shape Index, dalje u tekstu MSI). MSI se temelji na metodi prostorne analize engleskog naziva

Shape Index, čiji je rezultat primjene numerička vrijednost indeksa oblika (minimalna, maksimalna i prosječna) za svaki od promatranih skupova. U ovom radu MSI mjeri prosječan oblik uzoraka svakog tipa krajolika te uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like u cjelini.

MSI se za podatke vektorskog oblika dobiva na temelju formule (Lang i Blaschke 2010):

gdje je

p – opseg uzoraka,

a – površina uzoraka

MSI se odnosi na odstupanje oblika uzorka od oblika kruga (Lang i Blaschke 2010). Time MSI mjeri geometrijsku složenost uzoraka − veća složenost uzoraka znači veće vrijednosti MSI (Esbah 2009). Na temelju složenosti uzoraka, odnosno na temelju vrijednosti MSI u radu su definirani atributni opisi.

[3]Ukoliko je oblik promatranog skupa uzoraka jednostavniji, tj. sličniji je obliku kružnice, vrijednost MSI je bliža vrijednosti jedan (1). S druge strane, što je složeniji oblik promatranog skupa uzoraka, to je vrijednost MSI veća. To znači da uzorci linearnog oblika, oblika koridora te uzorci spiralnog i složenog oblika imaju veću vrijednost MSI od kompaktnih i zaobljenih uzoraka te uzoraka jednostavnog oblika.

Za stanje uzoraka krajolika korišten je pokazatelj indeks površine jezgre (engl.

Core Area Index, dalje u tekstu CAI) koji je izračunan na temelju podataka svakog uzorka u promatranom skupu (za tipove krajolika i krajolik Srednje Like u cjelini). CAI je numerička vrijednost koja označava omjer površine jezgre (engl.

Core Area, dalje u tekstu CA) i ukupne površine za svaki od promatranih skupova. Pri tome, što je dobivena numerička vrijednost CAI manja, to znači da je rezultat veće fragmentacije unutarnjih područja, tj. da je riječ o složenim ili izduženim oblicima jer je površina jezgre uzoraka manja, i obratno.

CA se dobiva kao rezultat primjene GIS metode za CA uzoraka kojom se dobiva numerička vrijednost (u ovom radu u km

2) koja se odnosi na ukupni CA za svaki od promatranih skupova. Može se reći kako je CA, u tehničkom smislu, jednak opciji prikaza prema unutrašnjosti metodi prostorne analize

Buffer.

Sintaksa naredbenog retka za

Bufferje (ESRI 2020):

<plaintext> Buffer_analysis <in_features> <out_feature_class> <buffer_distance_or_field> {FULL | LEFT | RIGHT | OUTSIDE_ONLY} {ROUND | FLAT} {NONE | ALL | LIST} {dissolve_field;dissolve_field...}

CA uzoraka zapravo označava središnji prostor uzoraka koji nije pod vanjskim utjecajima, dakle označava područje uzorka bez rubnog dijela. Pri tome je važno napomenuti kako veličina rubnog dijela (utjecaj izvana prema jezgri) uzorka ovisi o objektu istraživanja. Naime, riječ je o utvrđivanju efektivno korištenih površina u ovisnosti o kontekstu. Tako suNupp i Swihart (2000) pri istraživanju malih sisavaca na šumskom zemljištu koristili udaljenost rubnog dijela od 50 m.Túri (2010) pri istraživanju uzoraka krajolika za dva različita dijela krajolika koristio je udaljenost rubnog dijela od 10 m.Lang and Blaschke (2010) na različitim primjerima koristili su udaljenosti rubnog dijela od 5 m, 10 m, 20 m, 35 m i 50 m. U ovom radu se zbog svrhe rada te razine generaliziranosti podataka (100 m) koristi udaljenost rubnog dijela od 50 m za sve tipove krajolika i krajolik Srednje Like u cjelini.

Položaj uzoraka krajolika istražen je na temelju prosječnog indeksa susjednosti, korištenjem metode

Average Nearest Neighbor (

Spatial Statistics), dalje u tekstu

Average Nearest Neighbor. Temeljem određivanja radijusa udaljenosti pri čemu se određuje klasifikacija intenziteta oko svakog promatranog elementa (Pahernik 2000), ta metoda primijenjena je u svrhu utvrđivanja prosječne udaljenosti svakog od promatranih uzoraka krajolika prema najbližem susjednom. Pri tome se utvrđuje grupiranje, nasumičnost, odnosno raspršenost promatranih uzoraka krajolika.

Takva analiza susjedstva u ovom se radu provodi s vektorskim podatcima, uzimajući u obzir sve uzorke po tipovima krajolika, te krajolik Srednje Like u cjelini. S druge strane, u pojedinim radovima (npr.Faivre i Pahernik 2007, (Pahernik 2000, 2012) provodi s rasterskim modelom podataka pri čemu se promatraju samo ponikve.

Korištena je opcija te metode pri kojoj su uzorci krajolika prethodno pretvoreni u točke, odnosno centroide. Pri tome se mjeri udaljenost između lokacije centroida svakog uzorka i lokacije najbližeg susjednog centroida te se zatim mjeri prosjek svih izmjerenih udaljenosti (ESRI 2019).

Average Nearest Neighbor se računa po formuli (ESRI 2019):

– uočena srednja udaljenost između svakog uzorka i najbližeg susjednog

– uočena srednja udaljenost između svakog uzorka i najbližeg susjednog

d

i

– udaljenost između uzorka i i najbližeg susjednog

n – ukupan broj uzoraka

A – područje istraživanja

z

ANN

– z-vrijednost za

Average Nearest Neighbor

Rezultat primjene te metode su vrijednosti: uočena srednja udaljenost (engl.

Observed Mean Distance),

[4] očekivana srednja udaljenost (engl.

Expected Mean Distance), omjer najbliže udaljenosti (engl.

Nearest Neighbor Ratio),

z -vrijednost i

p -vrijednost.

[5]Ukoliko je vrijednost omjera najbliže udaljenosti manja od vrijednosti jedan (1) − ukazuje na grupiranje, a ako je veća od vrijednosti jedan (1) − ukazuje na raspršenost uzoraka krajolika. Na temelju dobivenih vrijednosti, korištenjem te metode prostorne analize automatski su prikazani atributni opisi (grupirano, nasumično, raspršeno) koji su u radu navedeni i objašnjeni.

Područje istraživanja

Područje istraživanja ovog rada je Srednja Lika. Prema aktualnoj administrativno-teritorijalnoj organizaciji, Srednja Lika obuhvaća područje tri jedinice lokalne samouprave: Grad Gospić, Općinu Lovinac i Općinu Perušić, koje su sastavni dio Ličko-senjske županije. Ukupna površina područja istraživanja iznosi približno 1690 km

2. Na području istraživanja nalazi se 78 naselja – Gradu Gospiću pripada 50 naselja, Općini Perušić pripada 18 naselja i Općini Lovinac pripada 10 naselja.

Osnovu regionalne izdvojenosti Srednje Like čini orografski okvir kojeg sačinjavaju: gorski hrbat Velebit sa zapadne i jugozapadne strane, Ličko sredogorje s istočne strane i gorski masiv Resnik s jugoistočne strane. Središnji prostor Srednje Like odnosi se na Ličko polje, koje se smatra najvećim krškim poljem na području Republike Hrvatske. Jugoistočni dio istraživanog područja zauzima Lovinačko polje. Od ostatka područja Srednje Like odvojeno je kupastim humovima, odnosno uzvišenjima u kršu (sl. 1).

Raspon nadmorske visine područja istraživanja je između 461 i 1757 m, a prosječna nadmorska visina iznosi 740 m (Pahernik i Jovanić 2014). Naselja i područja čovjekovog djelovanja Srednje Like uglavnom su koncentrirana na središnjem prostoru – Ličkom polju.

Izgrađene površine te područja čovjekovog djelovanja zauzimaju ukupno 17,05 % površine Srednje Like. Naime, ukupna izgrađena površina iznosi 1,29 % površine Srednje Like. To se odnosi na ukupnu površinu naselja Srednje Like

[6] koja iznosi 0,66 % površine te na 0,63 % površine koja se odnosi na površine objekata s prometnom i gospodarsko-poduzetničkom djelatnosti (autocesta i pripadajuće zemljište, poduzetničke zone, gradilišta i mjesta eksploatacije mineralnih sirovina). Na poljoprivredno zemljište odnosi se ukupno 15,76 % površine Srednje Like (CLC 2012).

Strukturna obilježja uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like prema tipovima krajolika

Prema postupku navedenom prethodno u radu, na temelju podataka o zemljišnom pokrovu/načinu korištenja zemljišta iz 2012. godine, područje Srednje Like svrstano je u šest tipova krajolika (sl. 2):

Izgrađeno zemljište

Travnato zemljište

Poljoprivredno zemljište

Šumsko zemljište

Grmlje/sukcesija šume

Vodene površine

Na uzorcima tipova krajolika provedene su analize koje se temelje na više pokazatelja i korištenju metoda prostorne analize. Njihovom primjenom dobivene su vrijednosti za

oblik,

položaj i

stanje uzoraka tipova krajolika Srednje Like i krajolik Srednje Like u cjelini. Sve dobivene vrijednosti su prikazane utablici 1.

Tablica 1. Rezultati promatranih pokazatelja za oblik, položaj i

stanje uzoraka krajolika Srednje Like (2012. godina)

Napomena: U poglavlju „Metodološke napomene vezane uz korištene metode prostorne analize“ detaljno su objašnjene korištene metode i značenja atributnih opisa.

Tip krajolika

Izgrađeno zemljište na području Srednje Like sastoji se od ukupno 17 uzoraka. Taj tip krajolika pretežno je položen bliže središnjem dijelu. Sadrži naselja s većim brojem stanovnika, odnosno naselja s većom koncentracijom izgrađenosti te objekte s prometnom i gospodarsko-poduzetničkom djelatnosti (autocesta i pripadajuće zemljište, poduzetničke zone, gradilišta i mjesta eksploatacije mineralnih sirovina). Vrijednost MSI je među ostalim tipovima krajolika najveća (4,19). S obzirom na tu vrijednost, oblik uzoraka tog tipa krajolika može se opisati kao složeniji. To je naročito izraženo kod izduženih uzoraka, kao što je autocesta i pripadajuće zemljište. Među ostalim tipovima krajolika Srednje Like, kod tipa krajolika

Izgrađeno zemljište vrijednost CAI je najmanji (43,91 %). Naime, kod tog tipa krajolika je najveći broj uzoraka sa složenim ili izduženim oblikom zbog čega je površina jezgre uzoraka najmanja. S obzirom na položaj uzoraka tog tipa krajolika, riječ je o raspršenom položaju uzoraka. To znači da je na području Srednje Like kod tog tipa krajolika prosječno velika udaljenost središta uzorka do središta susjednog uzorka.

Tip krajolika

Travnato zemljište na području Srednje Like sastoji se od ukupno 99 uzoraka. Na području Srednje Like taj se tip krajolika odnosi na pašnjake i prirodne travnjake, koji se razvijaju kao rezultat prve faze sukcesije vegetacije. Naime, od završetka Drugoga svjetskog rata stvorena je „osnovna infrastruktura i provedena inicijalna industrijalizacija regije“ (Pejnović 1985:66) i započeo je složeniji gospodarski razvoj. Time se, u skladu s društveno-gospodarskim procesima (deagrarizacija, deruralizacija, urbanizacija, smanjenje ukupnog broja stanovnika, starenje stanovništva) stanovništvo Srednje Like sve manje bavi poljoprivredom. Zapuštanje, odnosno ekstenzifikacija korištenja poljoprivrednih površina i napuštanje njihove obrade dovodi do prirodnog procesa sukcesije vegetacije, tj. prirodnog pošumljavanja (Fuerst-Bjeliš i dr. 2000). U prvoj fazi sukcesije vegetacije na poljoprivrednom zemljištu izrasta nisko raslinje koje se može nazvati travnatim zemljištem. Zatim, ukoliko dođe do druge faze sukcesije, na travnatom zemljištu se razvija srednje visoko raslinje – grmlje, odnosno sukcesija šume. Iz takvog srednje visokog raslinja se u završnoj, trećoj fazi sukcesije vegetacije postepeno razvija visoko raslinje − šumsko zemljište.

Obilježja tipa krajolika