1. Introduction

Corresponding with the Ottoman incursions into areas of Southeastern Europe from the sixteenth century onward, the geostrategic and political interest in the Croatian lands increased (Marković 1993, 134). As Eastern European Christian regions, the medieval Kingdoms of Bosnia, Croatia and Slavonia, also including parts of Hungary, have gradually been incorporated under the Ottoman reign after strong diplomatic actions. These were preceded by devastating light cavalry raids of

Akindji troops, infantry formations and even

Janissary elite. The deterioration of the Slavonian estates caused by military attacks from the Ottoman krajina (

serhat) started after the fall of the Kingdom of Bosnia, followed by the establishment of the Bosnian Sandžak in 1463. The newly gained territory was incorporated into the Ottoman Rumeli Eyalet (Moačanin 1999, 25;Mujadžević 2012, 102). Political instability among the local nobility also contributed to the defeat of the Croatian-Hungarian rule in the Slavonian lowland between the Drava and Sava. After 1537, this territory was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire (Holjevac and Moačanin 2007, 13;Moačanin 2001, 7). Such political, but also dynastic, cultural and economic turmoil has surely attracted the interest of European political elites, especially those economically and politically interested in their lost possessions (such as the Hungarians or Habsburgs). Since the Ottoman presence in this Catholic area indicated cultural, religious, economic, and other shifts, it consequently created fear in Western Europe, but also drew the interest for “the Ottoman” Other and the exoticness of Eastern European regions under Ottoman rule in both military and cultural circles (Bisaha 2004;Goffman 2002, 224;Lauer and Majer 2014;Theilig 2011, 1-10). Cartographic interest increased especially after the 1699 Great Turkish War warfare turning point, which accelerated the Ottoman withdrawal. The Ottoman decline, caused by a gradual onset of social crisis, corruption, military and economic collapse of the Ottoman-Turkish system of timars

[1], alongside the strengthening of the Anti-Ottoman aliances among its European political rivals and military opponents from the mid seventeenth century,enabled Croatia to regain the majority of its sixteenth century possessions, Slavonia

[2] included (Holjevac and Moačanin 2007, 164-168;Mujadžević 2012, 105).

Regardless of the increased European interest in geographical discoveries in the New World, reinforced commercial goals and accumulation politics focused on the colonisation of India and Africa, Eastern Europe still attracted significant interest in demographic complexity and in an economic exploitative sense. The weakening of feudal anarchy, the introduction of enlightened absolutism in Central and Southeastern Europe, parlamentarism, liberalism and secularization of Northern Europe accelerated technical revolutions and evolutions of Western societies and economies (Adamček 1981, 62-63). In such a world not just political as well as cultural interest in the distant Eastern Europeans prevailed, from academic research curiosity to exotic amusement for elites

[3], described in travelogues or depicted in paintings and maps.

[4] Similarly to maps, early modern travelogues and guidebooks might additionaly reveal a sense of real place in history, offering the author's insight into categories like ethnic/religious/cultural consciousness and patriotic awareness of local people. Highly important in that sense was the recognition of separate sovereign political bodies in Southeastern Europe (Black, 1997: 8). This may explain why cartographic attention has been paid to the mapping of Croatia and its neighbouring countries, both coastal and continental parts. Yet, the latter was the last existing area under the rule of the Croatian Diet, representing at the same time the geographically marginal but politically important bulwark of Christianity (

Antemurale Christianitatis) as the shield against the Ottoman pressure (Adamček 1981, 17;Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017, 49;Mlinarić, Faričić and Mirošević, 2012: : 145-176). Due to the division of the Croatian lands between various superpowers such as the Ottomans, Venetians and the Austrian branch of the Habsburg Empire, many cartographers were able to draw inspiration from each other in order to depict the area as accurately as possible, searching for information among the most reliable sources available (the Croatian students, mapmaking apprentices, or other immigrants from Croatian areas) (Adamček 1981,18;Budak 2007,104-109;Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017, 37-40;Mlinarić, Faričić and Mirošević, 2012: : 151-153). Cartographers from Austria, Italy and Hungary, as representatives of these neighbouring powers ruling over some of the Croatian territories had the privilege of being acquainted with the region or had all the prerequisites for such an advantage (Kozličić 1995;Marković 1993;Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017;Pandžić 2005;Slukan Altić 2003). The Southern Slavonian administrative unit of the Military Border on the river Sava (

Militärgrenze), predominantly the Slavonian Military Border, organised to prevent or block Ottoman trans-border military campaigns was self-financed but controlled by the Habsburg administration (

Hofkriegsrat). Therefore, this territory was of the utmost interest for the Habsburg military officers, known as the most accurate mapmakers of the time. Consequently, the early modern maps of Slavonia, primarily issued by military engineers after carefully conducted terrain surveys offered comparatively much more reliable cartographic data than any other cartographic tradition (Adamček 1981: 18;Štefanec 2016: 52). During the eighteenth century Austrians (and their accomplices) became much more devoted to geopolitical information, especially after the conduction of the Peace Treaties and founding of the Border Delineation Commissions. These committee endeavors resulted with precise borderline maps of the mutually agreed dividing lines after the Peace Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, furnishing their maps during the century with additional geo-military data, like plans of the fortifications or strategically important communications (commercial, sanitary or even postal) and corridors (Weigel 1700;Gadea 1718).

The Dutch, to the contrary, despite of being the pioneers of the cartographic tradition or even more precise - a mode of mapping in the late sixteenth century, had less knowledge because they were not in direct contact with the region (Marković 1993, 137-148). Throughout the century, they rather continued to rely on German/Austrian or French map templates and have continued to follow earlier mapping experts while reproducing and re-printing their own synthesis of collected cartographic information. However, this did not stop them from issuing maps of Croatia and surrounding countries. Regarding such a reality, the authors of this paper selected and consulted some of the most representative but distinctive (by thematic approach, purpose, scale, etc.) early eighteenth century cartographic archival sources from several cartographic traditions or mapping modes, comparing them additionally with narrative sources like travelogues. By conducting a transdisciplinary, comparative qualitative analysis they tend to reveal the traces of widely-known original cartographic elements on Dutch maps (as images) of Slavonia. Since the Dutch used high aesthetics in visual presentation and were known for their interest in politically fascinating spaces, human representations and even in attractive images of less known exotic and even fantastic areas (Slukan Altić 2003: 114;Black, 1997: 8-12), these elements were sought after. The main goal of this study is to reveal the specific style, if such existed, in which eighteenth century Dutch mapmakers depicted Slavonia. Consequently, there has been made use of some of the most representative Dutch eighteenth-century maps which are preserved in the map collection of one of the most prominent among the national institutions (National and University Library in Zagreb) and in a private collection (Collectio Felbar). In addition to selected Dutch maps, Austrian, German and French maps have been compared in search for mutual influences and /or remarkable differences between various map traditions and/or mapping modes.

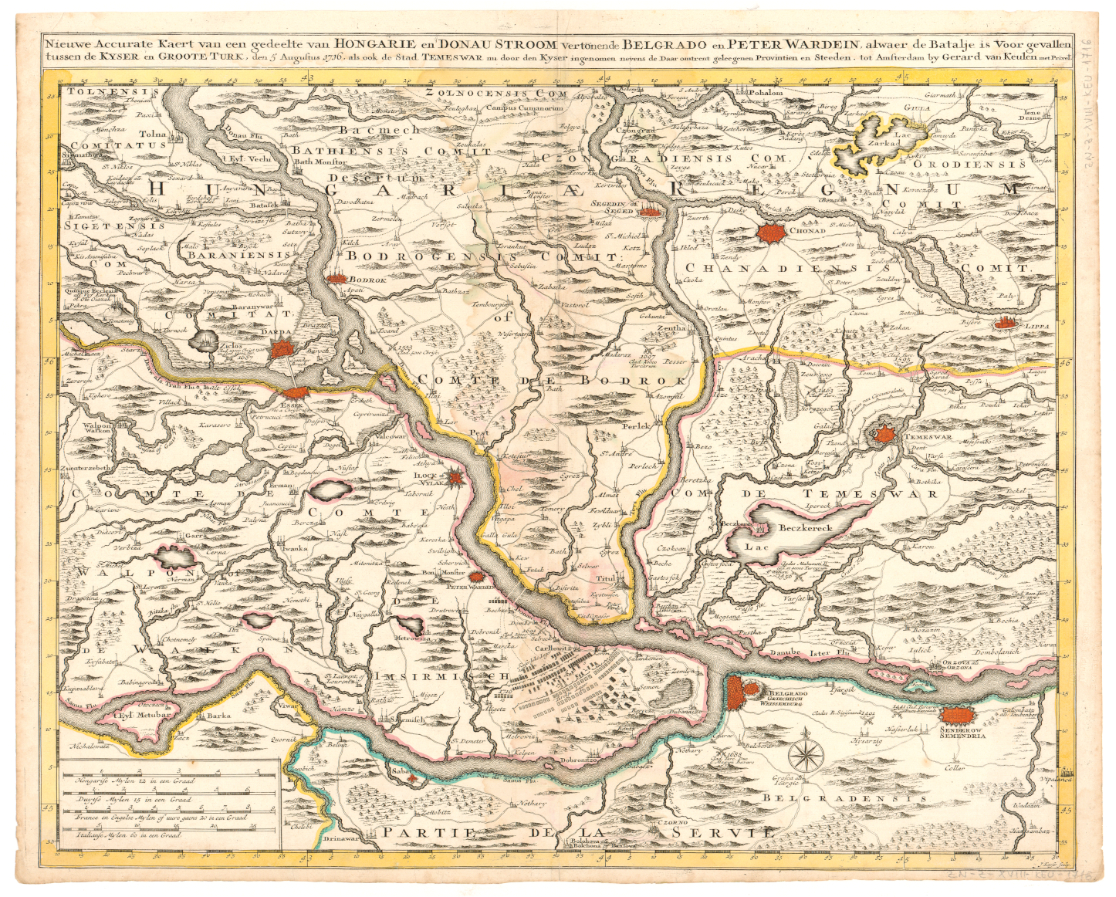

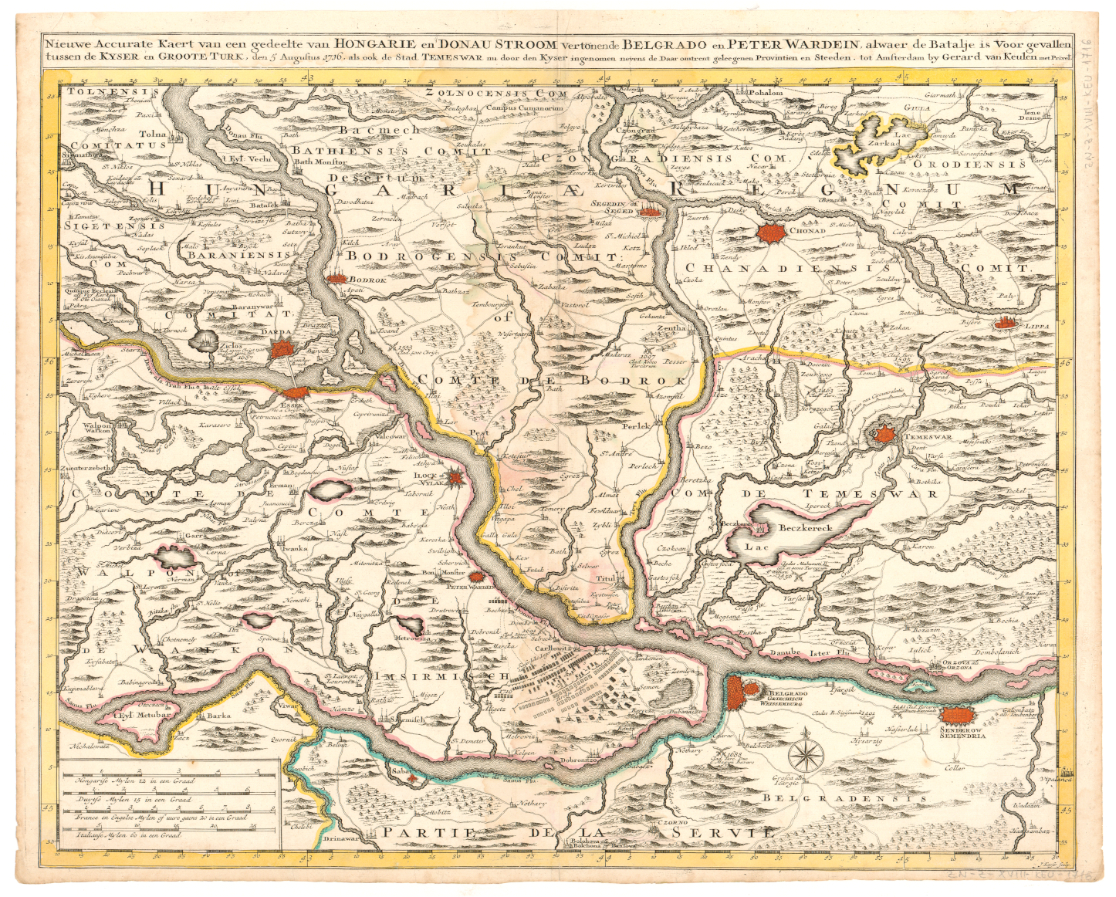

Fig.1 Gerard van Keulen, Nieuwe Accurate Kaert van een gedeelte van HONGARIE, 1716, ZN-Z-XVIII-KEU-1716, National and University Library in Zagreb / Slika 1. Gerard van Keulen, Nieuwe Accurate Kaert van een gedeelte van HONGARIE, 1716, ZN-Z-XVIII-KEU-1716, Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu

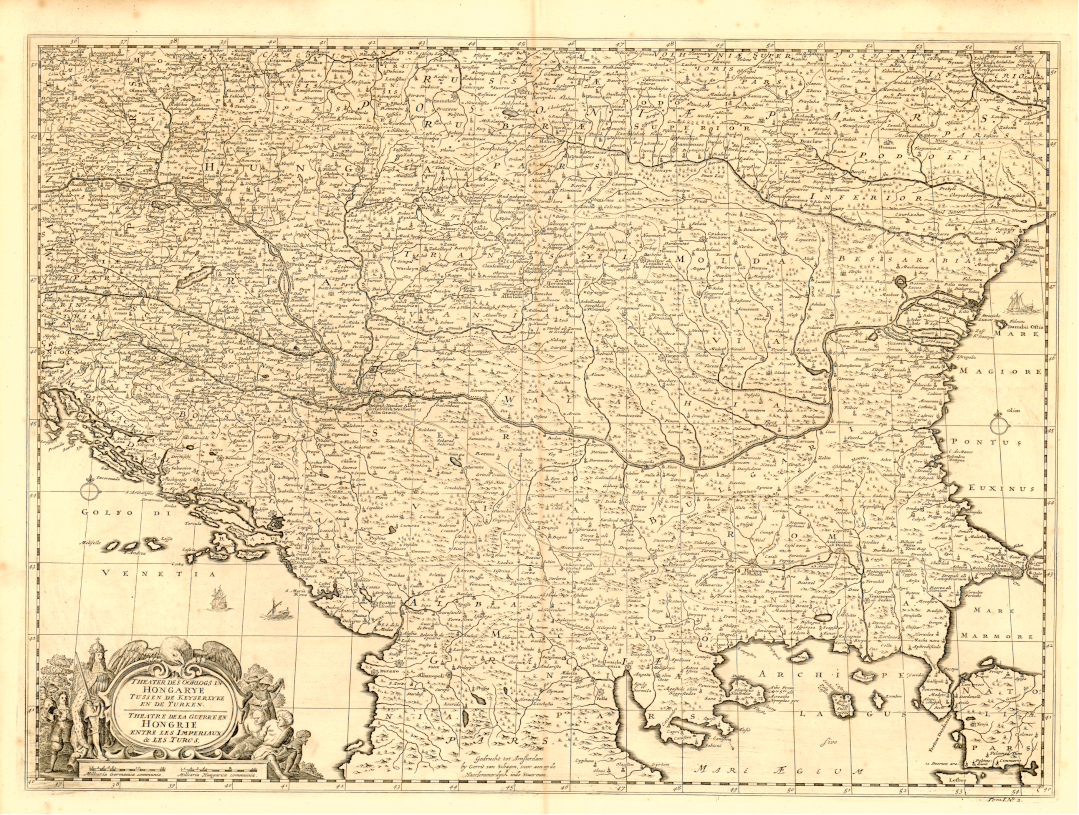

Fig. 2 Gerrit van Schagen, THEATER DES OORLOGS IN HONGARYE …., 1729, S-U-XVIII-27, National and University Library in Zagreb / Slika 2. Gerrit van Schagen, THEATER DES OORLOGS IN HONGARYE …., 1729, S-U-XVIII-27, Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu

Fig. 3 Joannes van der Bruggen, REGNUM SLAVONIAE, 1737., S-JZ-XVIII-139 (8), National and University Library in Zagreb / Slika 3. Joannes van der Bruggen, REGNUM SLAVONIAE, 1737., S-JZ-XVIII-139 (8), Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu

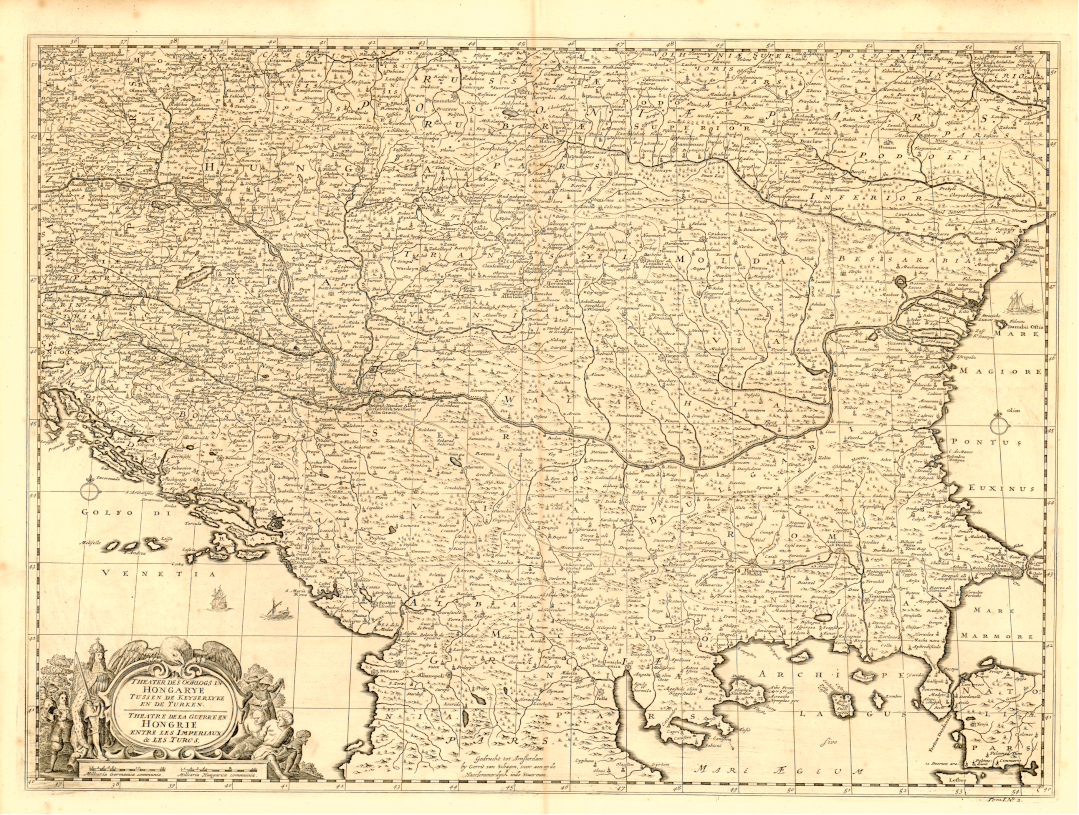

Fig. 4 Joachim Ottens, Novissima Tabula Hungariae et Regionum quondam ei unitarum ut Transilvaniae, Valachiae, Moldaviae, Serviae, Romaniae, Bulgariae, Bessarabiae, Croatiae, Bosniae, Dalmatiae, Slavoniae, Morlachiae et Republicae Ragusinae, 1725, Collectio Felbar, No 437. / Slika 4. Joachim Ottens, Novissima Tabula Hungariae et Regionum quondam ei unitarum ut Transilvaniae, Valachiae, Moldaviae, Serviae, Romaniae, Bulgariae, Bessarabiae, Croatiae, Bosniae, Dalmatiae, Slavoniae, Morlachiae et Republicae Ragusinae, 1725, Collectio Felbar, No 437.

2. The Cartographic Connection between the Low Countries and Croatian Lands

The contextual framework for the Dutch cartographic understanding of the geostrategic importance of Slavonia in European history also relied upon complex and inconsistent terminology of the area. The name Slavonia or “Sclavonia” was used from the Middle Ages onward, for the first Croatian state on the one hand and for the territory of the Eastern Adriatic hinterland populated by the Slavic people (

Sclavi,

Sclavini,

Sclavones) on the other. Slavonia experienced various territorial and other kinds of changes such as the shift of the very name, which was used for slightly different areas and political entities from medieval to early modern times (Bali 2014;Budak 2007;Marković 2005, 13;Pandžić 2005, 49).

Furthermore, some Dutch and Flemish travelogues from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries prove this practice, occasionally relating the name of Slavonia to the Adriatic coastland, presumably recognizing the Slavic languages spoken there. According to some travellers, such as Jan Want in 1516, Istria also belonged to Slavonia, while Jan Aerts in his 1481 travel report and Jan Somer in 1590 believe that Istria and its towns of Poreč, Rovinj and Pula belonged in Hungary, by which they probably meant that it belonged to the Hungarian crown. Joos van Ghistele also paid attention to the territorial structure of this area. According to his travel report from 1481, islands such as Pag belonged to Slavonia, and Budva (

Boudewa) was the last town to fall under the power of Slavonia. (Want 1896, 167;Aerts 1484, 42;van Ghistele 1998, 49-57). Some of these authors might have even been influenced by usual geo-cartographic misunderstandings of the region, reflected in works of contemporary Netherlandish mapmakers like Mercator, which are to be discussed later in the text.

The Ottoman penetration into Europe imposed the importance of Slavonia for the European superpowers. Bordering with the Ottomans even increased the frequency of Slavonia appearing on maps dedicated to the region of Hungary, facing the territories of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina belonging to the Ottomans (Marković 1993, 234). This made Slavonia highly important for several mapmakers. Simultaneously, the cartographic field of borderland mapping experienced a huge step towards applied geodesy and higher accuracy, as well as amplifying the significance of military geodetic surveying, mathematics and scale-based topography rather than the artistic aspect in maps. Compared to the Dutch mapmakers the Habsburgs military engineers had much more experience in these fields. The images of Slavonia in Dutch cartography also significantly depended on the general cartographic development in the Low Countries. Cities in its southern parts, such as Antwerp, experienced a golden age in the sixteenth century as an extremely convenient place for printers and publishers who shaped and published their works for the ever-growing curious international public (Koeman and van Egmond 2007, 1290;Koeman et al 2007, 1298;Marković 1993, 134). The publication of solid maps of various world locations made non-professionals familiar with the view of the already known Old World, including also some lesser-known European countries (Koeman et al 2007, 1374). From the seventeenth century, the economic and cultural centre and the majority of the cartographic knowledge shifted to Amsterdam, which entered its golden age. The city owed this largely to the Fall of Antwerp in 1585, which became dominantly Catholic again (Asaert 2004;Blom and Lambrechts 2014, 149-152;Zandvliet 1985, 38). Many of the protestant (Calvinist) intellectuals from the Southern part of the Low Countries settled in Amsterdam, thus cartographic production continued to evolve through the seventeenth century. According to Koeman, Schilder and some other researchers, the main causes the “industry” gradually passed to Amsterdam as a better alternative to Antwerp were “travel for commerce and discovery, the war against Spain, geographic changes within the region and the influence of immigrants from the southern provinces” (Koeman et al 2007, 1299-1300, 1305).

Consequently, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are known in the history of cartography as “the century of atlases” or the most prolific and important age for the development of artistic aesthetics in the Dutch cartographic tradition. The eighteenth century was again on some occasions overburdened with an over-decorative narrative, developed calligraphic and excessive ornamentation (Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017, 28). From that period onward, new players in map production, such as France and England entered the scene and it became more difficult for the Low Countries to maintain their "monopoly" and leading role (Zandvliet 1985, 2, 93). The importance of military maps, in particular in war-affected areas like Southeastern Europe was further developed, which was clearly visible in the total map production of that time (Fürst-Bjeliš and Zupanc 2007, 7-8, 11;Marković 1993, 234, 241;Marković 2005, 17;Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017, 51;Sills 2007, 981-1002, 991). To conclude, Mercator, Ortelius, Blaeu, and the like were pioneers in representing Croatia on early modern sixteenth and seventeenth century general or regional maps, with significant interest in borders of medieval Kingdoms of Croatian lands (Slavonia included) (Slukan, 2003: 115). But the contribution of the eighteenth-century Dutch cartographers to the understanding of Slavonia remained relatively underexposed. Besides, some of their maps were reprints or additions to new atlases and therefore still reflecting the images and compiling the data from the previous centuries

[5], especially regarding their modest direct personal experience in data gathering (Fürst-Bjeliš and Zupanc 2007, 7-8;Mlinarić and Miletić-Drder 2017, 51;Lučić, I, 1730). Similar practice occurred in narrative sources throughout the early modern period. Flemish travellervan Ghistele (1998) in 1481 clearly indicated that Slavonia used to be a kingdom once upon a time, to which all other lands or regionims he used for corresponding territories, such as Dalmatia, belonged. Since map-making was prolific in the eighteenth century, especially for the multiple bordering Croatian territories, the focus of this research is on the specific contribution of the Dutch.

3. Discussion

All selected maps are compared according to dominant cartographic features, regarding primarily landscape relief features, hydrographic elements, toponyms and bordering demarcations and fortifications.

3.1 Mapmaking Purposes and Scale-content Relations

Among the Dutch mapmakers many similarities but also some differences can be found. First, the maps byvan Schagen (1729,Fig. 2),Ottens (1725,Fig. 4) andvan der Bruggen (1737,Fig. 3) pay less attention to the landscape relief. The mountains are shown in a simplistic manner. Rivers such as the Drava and Sava are drawn in a relatively linear fashion, as are their tributaries. This can be explained by the focus of van Schagen's map being mainly on Hungary, as the title of the map confirms. Although at first glance van der Bruggen's

Regnum Slavoniae is different from van Schagen's, because of the immense colour palette and the specific focus on Slavonia as a region, not much attention was paid to the relief features of this map either. Hilly orographic formations that characterise Slavonia today are shown by van Schagen less accurately or not at all. The area of contemporary Serbia is again more mountainous, which was probably used as a tactic by the author to fill empty or less interesting areas, which were of considerably lesser importance for the general purpose of the map

Regnum Slavoniae. Differently from van Schagen's map, van der Bruggen has depicted the rivers and the hydrographic elements like meandering currents in much greater detail. This can mainly be explained by the scale difference and the focus on this map, which was entirely on Slavonia. The major hydronyms are written in Latin, indicating a general trend of this language supremacy in cartography. Additionally,van der Bruggen (1737) has used to work and obtain the data in Prague, Vienna, and Augsburg, thus representing as much of the Austrian as of the Dutch mode of mapping (see his alternative map in the Felbar Collection, dated in 1740). Such a complex and/or shifting cartographic identity and belonging manifestation were highly reflected in his cartographic style, blurring the clear distinction between the Dutch, Austrian or any other cartographic mapping mode or tradition (Slukan, 2003: 114;Black, 1997:10-12). Due to the scale used and area presented, bothvan Schagen (1729) andOttens (1725,Fig. 4), since presenting much broader space area, have shown much more reduced spectrum of simplified orographic and vegetation symbols.

Most toponyms were regularly rendered in Latin, while there was more arbitrary "freedom" about certain toponyms of less important settlements (econyms) and tributaries (potamonyms) (Faričić 2007, 148-179;Faričić et al 2012, 125-134).Van Keulen's map (1716,Fig. 1) has a clearer finish in terms of relief, which may be explained by the scale and the objective of the map. There are again no oronyms recorded in the region of Slavonia.Van Keulen (1716) attached importance to forestation, which was included more abundantly than on the other Dutch maps. In addition, the tributaries and the major river flows are elaborated in detail and, as in some other Dutch maps, are named in Latin which indicated their international importance and recognition. Ultimately, relief does not play an important part in any of the Dutch maps. The relief features on the maps of German mapmakerHomann (1745) and Austrian mapmakerReilly (1791) were slightly more elaborated than on most of the observed Dutch maps, but again not in detail. Since Slavonia is generally lowland, only less important neighbouring areas of the map were strategically coloured with mountain formations indicating vertical dynamics. Forested areas are not usually mapped in Slavonia, but the part of Hungary was given a few trees next to the rivers to fill in the blank spaces. Rivers such as the Drava and Sava are again represented in a somewhat simplistic linear manner, although the bending meanders with the tributaries are represented in more detail.

Moreover, the maps of Reilly, dating from the end of the century, can be hardly and not just in artistic aspects comparable to the Dutch maps from the beginning of the century, primarily thanks to the significantly changed Western European cartography of the late eighteenth century. The step towards scientifically established cartography, based on systematic geodetic surveying was taken primarily in Habsburg and French environments, but some reflections can be also seen among the Dutch authors. Unfortunately, the Dutch maps from the second half of the eighteenth century were poorly represented in the selected national or private map archives, thus these particular sources and mapping trends of the late eighteenth century have to be examined in some other study.

3.2 Cartographic Influences on the Use of Toponyms, Colour and Creation of Symbols

A striking novelty ofGadea's (1718),Schimek's (1788), (especially for neighbouring Bosnia), andHomann's maps (1745) is an abundance of toponyms, representing a clearly wider knowledge and better understanding of the region (Slukan Altić 2003, 230). This was not the case for the Dutchmen. For example, one can see both

Agram and

Zagrabia on the left side of van Schagen's map, both indicating the city of Zagreb, although

Zagrabia is situated closer to

Sisseg or

Sisaken (contemporary Sisak). This unintentional misconception when depicting Croatia has thus been adopted and spread among Dutch mapmakers for centuries. It was Mercator himself who included this obscure misinterpretation in his map. Thus it is clear that this eighteenth century mapmaker was also inspired and simultaneously informed by older cartographic models (German and Italian), unselectively adopting information from both of them, which was a common practice of the time. Although van der Bruggen had not made the same mistake about Zagreb as van Schagen, he opted to highlight the religious importance of

Agram using corresponding graphic symbols. As the episcopal seat,

Agram stood out from the rest of the towns on the map, emphasized by a very recognizable sign of the cross on the cathedral's tower. In opposition to copying older data, the Habsburg military mapmakerGadea (1718) has recorded absolutely new and accurate positions of 68 exact and named bordering stones or toft land markers for the borderline delineation southern of the Sava River. It was agreed by the Peace Treaty (of Passarowitz/Požarevac 1718), which was also conducted and carefully drawn on maps specifically issued by the Border Commission. Generally, these Peace treaties acted as milestones since their purpose was determining the new Habsburg-Ottoman border. Consolidation of territorial sovereignty, along with the spread of the authorities (governmental, legal, political, confessional) led to implementation of firm frontiers, needed by the growing Habsburg bureaucracies (Black 1997: 17). Therefore, a detailed mapping of the border area had to be performed, which highly contributed to improving the quality of geographical knowledge of the border parts of Slavonia but also of the general geographies along the borderlines.

The inspiration and influence of the “fathers of cartography” from previous centuries, namely Mercator, on the eighteenth-century Dutch mapmakers is also reflected in the fact that van Schagen had recorded contemporary Nova Gradiška and Bosanska Gradiška as

Gradiskia and

Gradiskia Turcicum. Moreover, he has indicated the importance of older boundaries, which existed prior to the Ottoman arrival. After all, the Treaty of Karlowitz (signed in 1699) and of Passarowitz (signed in 1718), were the milestone after which most territories in question were regained by Croatia and Slavonia (Fodor and Dávid 2000;Pešalj 2010, 29-42;Slukan-Altić 2003, 242;Tracy 2016, 5, 356). Van Schagen's map appeared in 1729, when the Ottomans largely left the area around Požega (

Posega) after their defeat in the 1691 Battle of Slankamen (Slukan-Altić 2003, 140). This is yet another sign that van Schagen, as a Dutch mapmaker, relied on older maps. A similar trend can be seen on van der Bruggen's map, namely in the “recycled” toponyms.

[6] The French map of Delisle (1717) has reflected the direct influence and insight of the 1699 Bordering Commission, since one of its co-authors was not just a member of this delineation body but its head personally, count Luigi Fernando Marsigli (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017: 167-168).

Differences also appear when selecting and depicting the most important fortifications in Slavonia, either by use of symbols or colour

[7]. For van Schagen, Požega held the most important defending function as a fortification and thus differed from the other towns. Gradiška and Osijek (

Ezzech) were depicted by van Keulen, van Schagen and van der Bruggen, who have accentuated their urban but again slightly bordering context with only a few turrets. In contrast to van Schagen, van der Bruggen highlighted the fortified towns of Osijek (

Eszek), Slavonski Brod (

Brod), Ilok (

Illok), and Varaždin (

Varasdin) with a red colour. Požega (

Possega) was less in the spotlight, although its name appeared in the same font. The fact that these aforementioned towns were marked red on van der Bruggen's map can be explained by their prominent location on the borders, with their strategic and military importance. Ivanić Grad (

Ivanitz), Kraljeva Velika (

Kraliovavelika) and Nova Gradiška (

Gradiscia) are also characterised by detailed fortifications, although not coloured in red. In addition, Slavonski Brod had both a red and colourless fortification, which indicated its strategically important but somewhat ambivalently complex position. The Austrian mapmakers showed similarities to the Dutch in depicting fortified towns. The red colour and symbols of fortified architecture (turrets) were usually used for the majority of militarily important border towns. Some of the turrets on the Dutch maps were clearly marked with a symbol of the cross indicating that these towns belonged to the Christian territory. Van Keulen used the same cartographic pattern on his map. On this particular map specimen it is not possible to find any towers with the recognizable crescent symbols on the other side of the clearly colour-coded boundaries. This practice of political authority identification is for example visible in the Italian map

Tvto il Côtado di Zara e Sebenicho byPagano (1530). He clearly depicted the distinction between the Ottoman and Christian territories in Dalmatia by using flags with crescents on turrets at the Ottoman borderland (

serhat). The same effect of the border delineation with the exact borderline and with consistently differentiating cartographic symbols of identity (a cross for Christian-Venetian settlements, and a crescent for Muslim-Ottoman places) has been even better recorded on the Dutch map of Northern Dalmatia byJan Janssonius (1646).

Similarly as van der Bruggen, van Keulen also opted to apply colour, largely to delineate the various territories. Osijek (

Essek), Ilok (

Ilock or

Vylakv), Petrovaradin (

Peter Warden) and a large number of other towns of lesser importance have been given a clear red colour, as in van der Bruggen's case, to highlight their strategically important borderland location. However, Osijek did stand out from the other towns by van Schagen's addition of the

Ezzech brug (and van Keulen's

Essecker Brück, written in German fashion), where the word

brug means bridge in Dutch. Interesting to note is that the wooden bridge built by Mimar Sinan for Suleyman, was actually burned down in 1686, which is again an indication that both Dutchmen were inspired by older traditions and have depicted some historical characteristics of the region from its Ottoman period (Haničar Buljan et al 2014). Whereas this bridge was of great importance during the Ottoman reign and therefore often noticed by many travellers from Western Europe. The Englishman Edward Browne even recorded a drawing of the wooden bridge in his travelogue from 1673 (Brown 1673). Another illustration of the bridge has been made by a Flemish painter from the seventeenth century. In the book depicting the towns of Austria, the Antwerp Baroque artist Jacob Peeters drew the

Essekker Brugh as an introductory page to the chapter on towns of Lower Hungary (Peeters 1690).

The toponyms used for the region of Slavonia clearly point to additional inspiration, which was drawn from German and Hungarian mapmakers, while a slight Dutch-language twist has also been applied. Words such as "brug" and the way

Posega and

Sisaken were written indicate an expected Dutch-language influence on the Dutch mapmaking. Gerard van Keulen even combined the French and Dutch language by naming the Vukovar-Srijem County as

Comte de Walpon of [meaning “or” in Dutch]

de Walkon. Smaller tributaries such as

Krasiza of [“or” in Dutch]

Gasso Flu. or

Draw als Trah Flu. again point to the Dutch-language contribution. Dutch toponyms were used for important places. An example is the contemporary Hungarian town of Pécs, recorded on the map as

Quinque Ecclesiae als Vyff Kerken o[f]

t Ote Oiazak, representing a combination of Latin and Dutch. Considering the Dutch titles of the maps, van Schagen has chosen to include the word

Oorlog, meaning “war”, referring to the warfare climate at the Ottoman borderland. Just as in his map, Gerard van Keulen narratively (in the title) depicted Slavonia as a part of a larger unit. Furthermore, the word

Batalje in his map's title, a Dutch corruption of the French word

Bataille (battle), again indicates the military aspect and purpose of both maps.

What differentiates the Austrian and Dutch maps in comparison is mainly the strong focus on the territories, borders and details which aimed to emphasize the military purpose of the map. The boundary was drawn in a way to include the entire region of Srijem between the Sava and Danube rivers within the possession of Slavonia. The borderline demarcation and specific choice of the colour made the map exceptional. This also indicates the geostrategic reality since Southeastern Srijem was in Ottoman hands until the end of the Habsburg-Ottoman War of 1716-1718 (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017, 194). The dotted lines marked the Military Border, or the

Militär Gränze as Reilly himself called it. The other dotted line indicated the actual border formed after the Peace of Passarowitz in 1718. Remarkable are some other Reilly's lines, which were not to be found on any of the other maps. One line starts from Zemun (

Semlin) and continues all the way to Novska (

Nofska), with another branch towards Osijek (

Essek) and Požega (

Possega). These lines and points connecting the different urban settlements in Slavonia represented mail routes (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017, 194). These features rarely occurred on maps from earlier periods and once again demonstrated the change of the map production towards utilitarian mapmaking. Finally, it is remarkable howReilly (1791) recorded the region of

Kleine Walachey around the river Pakra (

Parka Fl.). This does appear only onDelisle's map from 1717, with old counties recorded, which was all based on Marsigli's direct information. According to Ankica Pandžić, the choronym

Kleine Walachey or

Mala Vlaška in Croatian, "often found between Civil Croatia and Turkish Slavonia around Pakrac" refers to the fifteenth and sixteenth century Vlach settlements with the duty to "defend the border from the Turks (…) Although the area was put back under county administration of Civil Croatia in the 1740s, the name

Mala Vlaška was retained on the maps till the end of the eighteenth century" (Pandžić 2005, 60). Besides, a new element of postal routes and stations has been recorded onReilley's postal map (1791), following the interests and needs of the growing Austrian administrative apparatus of the late eighteenth century (Slukan-Altić 2003; 230).

However, on his map Homann, while depicting much the same extent of Slavonia, also emphasized a French translation of the title in addition to a Latin one. Once again, the map has been coloured and edited with dotted lines clarifying where the territorial distinctions lie. It delineated the border between Slavonia as part of the Habsburg Empire and Bosnia as part of the Ottoman Empire after the conclusion of the Peace of Passarowitz. In addition, it is striking that Homann chosen to reproduce the red line that serves as the border in the old position as it was before the Peace Treaty of 1718. This shows that he relied on older maps of his predecessors. Therefore, it is also not surprising that Homann distinguishes himself from the rest of the analysed mapmakers by representing the state of affairs in the form of the earlier manorial estates, the so-called

Dominium. These estates can also be distinguished from each other by the use of dotted lines (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017, 176-177). As already mentioned, borderline delineations after the Peace Treaties' conclusions predominately defined the production of Austrian and German cartographers, such as in the case ofSchreiber (1749) and towards the end of the century in the case ofSchimek's map (1788).

3.3 Use of the Corations and/or the Cartouches

In opposition to balanced informative decorations on some of the German / Austrian maps, rather plain although strict in baroque style cartouche onSchreiber's map (1749), almost all of the cartouches of the Dutch maps are detailed. However, there is a complete lack of this kind of decorative iconography onSchimek's map (1788). The elaborated cartouche of van Schagen's map combined Habsburg symbolic elements and images of the Ottoman soldiers' inferior status. The map title hardly corresponds to the visual impression of both, the map itself and the cartouche, since the cartouche is much older. This is an example of how many Dutch cartographers, despite the growing influence and military importance of the mapmaking sector, still stuck to the particular artistic aspect of mapmaking (Zandvliet 1985, 2, 60, 93). Similar to van Schagen's cartouche, which was full of symbolism, van der Bruggen also made a statement with the decoration of three angels holding a map of a divided Europe. By adding important objects from Christian symbolism along the upper and lower edges of the map he emphasized the history of the suffering fate of this Christian region. His map is imbued with a Baroque style through the attention paid to the cartouches and the decoration, but also powerful colours. Such an obvious predominance of the artistic aspect is exactly what was considered to be the main reason for Amsterdam losing its prominence as an international centre for cartography, with other superpowers such as France and England taking over (Sills 2007, 991;Zandvliet 1985, 2). The focus of van Keulen's map was evidently on warfare since the words

Kyserlyke Leger have indicated the Imperial Army of the Habsburgs, while

Turckse Leger has referred to the Turkish Army. The same was confirmed by the title which brought news on the battle of 5

th of August 1716 between the Habsburg Empreror (

Kyser) and the Sultan (

Groote Turk). Quite the opposite, there is no Baroque cartouche on this map as there was on the others. Rather, van Keulen focused on the graphic scale with varieties of miles, specifically the Hungarian, the German, the French, English and Italian. He emphasized the empirical aspect of an eighteenth-century map, broadening its communication capacity. However, the similar Christian alliances' supporting aspect and the reference to the wide European tradition are reflected through the map. Van Keulen has additionally attached dates to some toponyms, mainly of victories or battles in general. One example is

rec. a Christ 1687, written in Latin near Osijek, highlighting the victory of the Christians over the Ottomans in the second battle of Mohács (Dupuy and Dupuy 1993, 638;Kinross 1977, 350-351). The Dutchmen were also used to highlighting the religious background of the region of Slavonia next to the predominant military purpose of the maps, again combining versatile map communication capacities. Along the eighteenth century the Dutch cartography was also confronted with various political interests for Slavonia. Besides the military importance of Slavonia, expressed by decorative war symbols in the graphic title cartouche on Ottens' map from 1725, further focus was stick to the political development and the establishment of borders on the Eastern European edges. Since the vast area presented on the map itself, geographical names and orography elements were slightly underestimated.

While onGadea's map (1718) aesthetics, especially of elaborated cartouches, were of immense importance, another Austrian representative,Reilly (1791) or GermanSchreiber (1749) expectedly did not opt for an artistic aspect to fill in the gaps on their maps, which underline the huge importance they paid to military, political and strategic contents and purposes of the map. Human figures were additional graphic elements for communicating (hidden) agendas. Next to the legend, used to clarify urban gradations and fortifications on Homann's map, the author added a cartouche with Austrian pivotal figures such as Barun Trenk. Aside from figures who played an important role in freeing Slavonia from the Ottoman regime, images of Ottoman soldiers further emphasized regional complexity and the importance of the unification of Christian states (Dupuy and Dupuy 1993, 638;Kinross 1977, 350-351).

Finally, it is important to reveal in what way the Dutch maps differ from other cartographic traditions that were also not in direct contact with Slavonia. Le Rouge's map of 1742 indicates in what respect the French cartographic production of the eighteenth century differed from the Dutchmen (Le Rouge, 1742). Slavonia on his map was, similar to van Keulen's and van Schagen's maps, part of a larger region. There are far fewer details than on van der Bruggen's map. What makes this particular cartographic item similar to the previous map is that colour has been added later to delineate certain territories, enlightening the political and military aspect. The Danube, Drava and Sava are again represented in a simplistic way with less meandering. Considering the toponymy, a certain level of French language adaptation among astionyms has appeared. Le Rouge does not write

Zagrabia or

Agram but adopted the Hungarian version

Zagrab, indicating his basin of sources, while Sisak seems somewhat Francized as

Sissck. Other toponyms that immediately catch the eye again relate to the defensive military character or structural organisation of Slavonia. In that case, the authors kept their original "standardised" names. Like the Dutch, onGadea's (1718) andReilly's (1791) maps important fortresses are coloured in red. Again, the importance of Požega (

Possega) and Osijek (

Essek), with its famous bridge becomes clear on Le Rouge's map. The author even recorded details of the newly built Northeastern Karl's bastion in Osijek, as the recent addition to the Habsburg defensive fortifications. Slavonski Brod (

Brodt) is not given the same status as the aforementioned towns and is only represented by a small tower as other second-rate towns. The military dimension can also be highlighted by the recorded dates of important battles. To the contrary, Le Rouge's map reflected other famous techniques of emphasizing the military importance by decorations, applying a detailed cartouche with the exotic elements like elephants and crocodiles. However, cannons, flags and various other weapons catch the eye in that sense even more. On the contrary toGadea's (1718), but similarly as the Dutchmen, Schreiber, Reilly and le Rouge, the other French author Delisle has also used graphic scale measurements in different sizes (miles of various provenance). While the toponyms and geographic grid made the map slightly different from the others, it is evident that much information was lacking. Thus it seems that French maps are in many ways comparable to the Dutch maps. This may suggest that despite their growing share of the cartographic production on the European scene, the French continued to draw inspiration from the aesthetics but also the cartographic style of the Dutch.

4. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to compare a small and heterogeneous but distinctive selection of the Dutch, Austrian, German and French maps from the first half of the eighteenth century in order to find out how Dutch mapmakers, who were not in direct contact with the region of Slavonia, mapped this strategically important Southeastern European border region. The selected Dutch maps of various scales and purposes, resulting in slight differences among them, were compared with maps created by French and Habsburg mapmakers, the latter being politically, and military connected with Slavonia and thus more familiar with it. The analysis of the chosen maps has not revealed huge differences between particular Dutch and Austrian maps, but it proved the changes in eighteenth century cartography, with increasing interest for the current political and geostrategic situation but also for more precise geodetic elements. Furthermore, the analysis of the French maps, which were also not in direct contact with Slavonia, proved similar findings with the Dutch cartographic tradition. The artistic narrative of previous centuries has been slightly receding to the erudite and information-driven approach. Furthermore, the military dimension started to dominate due to the geopolitical importance of Slavonia at the time, thus the focus in the majority of observed sources is mainly on the bordering issues and territorial presentations. These were the fields and skills highly appreciated and developed by the Habsburg military topographers, which can explain the comparatively higher numbers of geographical names recorded and specific geographic (topographic, hydrographic) elements drawn on Austrian maps.

In spite of the fact that the selected maps can not represent the Dutch cartographic tradition as a whole, this comparison reveals trends and tendencies that the Dutch cartographers strived to combine both, outstanding decorative content on the one hand and informative quality of mapmaking on the other. Consequently, the Baroque artistic aspect remains present, but the interest for particular border demarcation has obviously increased. However, the same tendency was also illustrated by Austrian and German maps since the authors have also included detailed and very elaborate decorative cartouche drawings. What have distinguished the Dutch and the German/Austrian cartographers, the latter strongly sharing and continuously developing similar mathematic postulates, with geodetic and utilitarian mapmaking views, were the additional more accurate geo-cartographic elements and terrain details in their works. An abundance of toponyms due to the better knowledge of the region among Habsburg topographers and engineers, the addition of legends, and inclusion of specific topographic elements to eighteenth-century Slavonia demonstrated in which area the Dutch cartographers were somewhat behind due to lack of first-hand geographical knowledge. Quite the opposite, some of the analysed Dutch cartographers have prevailed to focus on older maps as their inspiration, omitting the more recent data, even though they probably realised that much had changed over time. Furthermore, on the majority of the selected maps of relatively common types, scales and purposes but different provenances (the Dutch, Austrian or French), since all represent the perspective of the Christian West, the religious and even political distinction between the Christian and Ottoman possessions was either vaguely or blurry evident. Only a general impression loosely indicated the Ottoman presence or completely denied it. This practice of “silence” was highly noticeable during the Ottoman (Eastern-Muslim) penetration across the borderlines of once medieval kingdoms (Slavonia included) as the Eastern European edges.

Although this study tended to test the possibilities of a comparative analysis on rather limited cartographic archival data, it certainly confirmed the expected trends or existence of widely known quality elements of the Dutch mapping mode or even tradition on each and every observed Dutch map. Thus, it can serve as the starting point for the broader research of the images and perceptions of Slavonian early modern bordering territories among the mapmakers that were not very familiar with the Southeastern European geostrategic and political position and worked without accurate geographic/cartographic field information.

Explanatory note

Sclavonien

[8] op de kaert

[9]

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result of research within the Scientific project

Croatia - New Immigration Country? funded by the Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies.

1. Uvod

Usporedno s osmanskim prodorima na prostor jugoistočne Europe od šesnaestog stoljeća nadalje jača i politički, odnosno geostrateški interes za hrvatske zemlje (Marković 1993, 134). Osmansko je Carstvo postupno osvajalo jugoistočnoeuropska kraljevstva; srednjovjekovnu Bosnu, Hrvatsku i Slavoniju te dijelove Ugarske i uključivalo ih u sastav svoje države, dijelom i diplomatskim aktivnostima. Njima su obično prethodili devastirajući pljačkaški prodori lagane konjice - akinđija, pješačkih jedinica, pa i elitnih janjičara. Nakon pada Bosanskog Kraljevstva te uspostave Bosanskog sandžaka 1463. godine zaredali su vojni upadi iz osmanske krajine (

serhata) prema slavonskim posjedima. Novoosvojeni je prostor uključen u osmanski Ejalet Rumeliju (Moačanin 1999, 25;Mujadžević 2012, 102). Propasti hrvatsko-ugarske vladavine u nizinskom međurječju Save i Drave pridonijela je i politička nestabilnost lokalnoga plemstva. Cijeli je prostor nakon 1537. godine uključen u Osmansko Carstvo (Holjevac i Moačanin 2007, 13;Moačanin 2001, 7). Spomenute su dinastičke promjene, uz političke, kulturne i ekonomske mijene, izazvale pojačani interes europskih političkih elita, prije svega onih koje su imale ekonomske i političke interese na prostoru svojih izgubljenih posjeda, primjerice ugarskih ili habsburških. Osmanska prisutnost u prethodno katoličkom prostoru kao i spomenute kulturne, vjerske, ekonomske i ostale promjene posljedično su izazivale strah širom zapadne Europe. Ujedno su poticale i interes vojnih i kulturnih krugova za Osmanlije kao strance i „druge“ i “egzotizaciju” istočnoeuropskih posjeda pod osmanskom upravom (Bisaha 2004;Goffman 2002, 224;Lauer i Majer 2014;Theilig 2011, 1-10). Interes kartografa porastao je napose završetkom Velikog bečkog rata 1699. godine, koji je označio vojnu prekretnicu i ubrzao osmansko povlačenje. Propadanje osmanske države bilo je posljedica postupnog jačanja krize, osipanja društvenog poretka, korupcije te vojno-ekonomskog kraha osmansko-turskog sustava timara

[1]. S druge strane, pratilo ga je jačanje anti-osmanske koalicije eurospkih političkih rivala i vojnih oponenata tijekom 17. stoljeća. Spomenuti su procesi omogućili da Hrvatska dobije većinu svojih posjeda iz šesnaestog stoljeća, uključujući i Slavoniju

[2] (Holjevac i Moačanin 2007, 164-168;Mujadžević 2012, 105).

Usprkos jačanju europskih interesa za Velika geografska otkrića u Novom svijetu, za revalorizaciju komercijalnih interesa i za kolonizacijske politike akumulacije dobara u Indiji i Africi, istočna je Europa nastavljala privlačiti pozornost Zapada zbog svojih ekonomskih resursa i demografske složenosti. Slabljenje feudalne anarhije i uvođenje prosvijećenog apsolutizma u središnjoj i jugoistočnoj Europi, jednako su kao i parlamentarizam, liberalizam i sekularizacija sjeverne Europe utirali put tehničkoj revoluciji i evoluciji zapadnih društava i ekonomija (Adamček 1981, 62-63). U takvim se okolnostima pored političkog zadržao i kulturni interes za udaljene istočnoeuropske krajeve, u rasponu od znanstveno-istraživačke znatiželje do egzotične zabave za elite

[3], vidljiv u narativnoj formi putopisa ili grafičkih prikaza poput slika ili novih karata.

[4] Baš poput karata, ranonovovjekovni su putopisi ili putni dnevnici mogli otkriti informacije o povijesti nekog prostora te čak razotkriti autorova saznanja o etničkoj, vjerskoj ili kulturnoj osviještenosti pa i patriotizmu lokalnog stanovništva. U tom su kontekstu posebno važna bila saznanja o različitim suverenim političkim jedinicama jugoistočne Europe (Black, 1997: 8). To objašnjava pojačani kartografski interes za hrvatske i njima susjedne zemlje, bilo priobalja ili kontinentalne unutrašnjosti. Kopneno je zaleđe ujedno predstavljalo posljednji ostatak teritorija pod vlašću hrvatskih staleža i Sabora, koji je, iako u europskom kontekstu geografski marginalan prostor, istovremeno bio politički važan štit pred osmanlijskim pritiscima, s ulogom predziđa kršćanstva (

Antemurale Christianitatis) pressure (Adamček 1981, 17;Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017, 49;Mlinarić, Faričić i Mirošević, 2012: : 145-176). S obzirom na to da su hrvatske zemlje bile podijeljene na posjede Osmanlija, Mlečana i austrijske grane kuće Habsburg, mnogi su kartografi preuzimali inspiraciju jedan od drugoga, u cilju što točnijeg prikaza prostora. Informacije su nalazili među najpouzdanijim dostupnim izvorima podataka, poput hrvatskih studenata, kartografskih pripravnika ili drugih useljenika s ovoga prostora (Adamček 1981,18;Budak 2007,104-109;Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017, 37-40). Kako su austrijski, talijanski ili ugarski kartografi bili predstavnici susjednih političkih sila koje su vladale dijelovima hrvatskoga teritorija, bili su u prednosti jer su bolje poznavali prostor ili su barem imali pretpostavke za to (Kozličić 1995;Marković 1993;Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017;Pandžić 2005;Slukan Altić 2003). Na južnom dijelu Slavonije, uz rijeku Savu organizirana je administrativna jedinica Vojna krajina (

Militärgrenze) točnije Slavonska krajina, s ciljem zaustavljanja širenja i prevencije novih osmanlijskih prekograničnih upada. Premda se samofinancirala, kontroliralo ju je Dvorsko ratno vijeće (

Hofkriegsrat) u Beču. Istodobno je taj prostor bio iznimno zanimljiv habsburškim vojnim časnicima i inženjerima, poznatima upravo po najpreciznijoj kartografiji toga vremena. Stoga su i njihove ranonovovjekovne karte Slavonije izrađene na temelju preciznih terenskih izmjera bile komparativno znatno pouzdanije i točnije od karata predstavnika drugih kartografskih tradicija (Adamček 1981: 18;Štefanec 2016: 52). Tijekom 18. stoljeća Austrijanci i njihovi suradnici više su pažnje posvećivali geopolitičkim informacijama, posebno nakon potpisivanja različitih mirovnih ugovora, odnosno formiranja komisija za razgraničenje. Njihovi su napori rezultirali preciznim kartama razgraničenja, kao sporazumno dogovorenim linijama razgraničenja nakon sklapanja Karlovačkog mira 1699. godine. Karte spomenute Komisije dopunjavane su tijekom stoljeća novim vojno-geografskim podatcima, primjerice planovima utvrda ili strateški važnim komunikacijskim pravcima i koridorima (trgovačkim, javnozdravstvenim ili čak poštanskim) (Weigel 1700;Gadea 1718).

Za razliku od njih predstavnici nizozemske kartografske tradicije odnosno prepoznatljivog modela kartografske produkcije s kraja 16. stoljeća, premda su pionirski kročili putem kartografskog razvoja, raspolagali su s manje praktičnih znanja o predmetu kartografskog prikaza, između ostaloga i zato jer nisu bili u direktnom kontaktu sa slavonskim prostorom (Marković 1993, 137-148). Tijekom stoljeća su se nastavili oslanjati na njemačke i austrijske, odnosno francuske katografske predloške i stručnjake u opetovanom recikliranju i ponovnom tiskanju starih sinteza koje su okrupnjivale prikupljene geografske podatke iz prethodnih vremena. No to ih ipak nije sprječavalo u izradi karata hrvatskih i susjednih zemalja. Stoga su autori ovog rada izabrali nekoliko reprezentativnih, premda raznovrsnih (tematski, namjenom i mjerilom) kartografskih izvora različitih kartografskih tradicija, odnosno načina kartiranja s početka 18. stoljeća za transdiciplinarnu i komparativnu kvalitativnu analizu. Dodatna je komparacija karata provedena u odnosu spram narativnih izvora poput putopisa. Cilj studije je identifikacija tragova prepoznatljivih nizozemskih kartografskih elemenata na kartama kao slikama Slavonije. S obzirom na visoke nizozemske estetske kriterije vizualne prezentacije i interes za politički zanimljive prostore, prikaze ljudi pa čak i privlačne slike manje poznatih egzotičnih krajeva, to su bili elementi za kojima se u istraživanju tragalo (Slukan Altić 2003: 114;Black, 1997: 8-12). Primarni je cilj studije bio detektirati prepoznatljiv stil, ako takav postoji, koji bi bio specifičan za nizozemske karte Slavonije osamnaestoga stoljeća. Stoga su korištene reprezentativne nizozemske karte osamnaestoga stoljeća koje se čuvaju u zbirci karata jedne od najznačajnijih nacionalnih ustanova (Nacionalne i sveučilišna knjižnica (NSK) u Zagrebu) te u jednoj od privatnih kartografskih zbirki (Collectio Felbar). Pored odabranih nizozemskih karata u studiji su uspoređene i austrijske, njemačke te francuske karte u potrazi za međusobnim utjcajima, odnosno prepoznatljivim razlikama među predstavnicima različitih kartografskih tradicija i obrazaca kartiranja.

2. Kartografske veze Nizozemske i hrvatskih zemalja

Razlog slabijeg poznavanja geostrateške važnosti Slavonije za povijest Europe među nizozemskim kartografima počiva dijelom na složenoj i promjenjivoj terminologiji imena pokrajine. Ime

Sclavonia koristilo se od srednjega vijeka, bilo u imenu prve hrvatske države, bilo općenito za prostor istočnojadranskoga zaleđa koje su naseljavali Slaveni (

Sclavi,

Sclavini,

Sclavones). Slavonija je u tom smislu prolazila kroz različite mijene, uključujući i promjene imena koje se koristilo za donekle različite prostorne i političke entitete u razdoblju od srednjeg do ranoga novog vijeka (Budak 2007;Marković 2005, 13;Pandžić 2005, 49;Bali 2014).

Štoviše, neki su nizozemski i flamanski putopisci tijekom 15. i 16. stoljeća potvrdili tu praksu, gdjekad povezujući ime Slavonije uz jadransko priobalje, vjerojatno zbog prisutnosti slavenskih jezika na spomenutom prostoru. Prema nekim putnicima, poput Jana Wanta 1516. godine, Istra je također bila dio Slavonije, dok su Jan Aerts u svojem radu iz 1481. te Jan Somer iz 1590. godine zabilježili da Istra i gradovi poput Poreča, Rovinja i Pule pripadaju Ugarskoj, pri čemu su vjerojatno mislili na posjede ugarske krune. Joos van Ghistele također je posvetio pažnju prostornim odnosima u Slavoniji. Njegov putopis iz 1481. navodi otok Pag kao sastavni dio Slavonije, dok je Budva (

Boudewa) posljednji grad koji je dospio pod upravu Slavonije (Want 1896, 167;Aerts 1484, 42;van Ghistele 1998, 49-57). Na neke od tih autora utjecalo je uobičajeno geo-kartografsko nerazumijevanje, odnosno krive informacije koje su se o regiji širile, a koje se moglo pronaći u radovima njima suvremenih nizozemskih kartografa poput Mercatora, što je tema kojom ćemo se pozabaviti nešto kasnije u tekstu.

Osmanski prodor u Europu nametnuo je pitanje Slavonije kao važno, posebno među najmoćnijim europskim državama, pa je razgraničenje s Osmanlijama omogućilo da se Slavonija sve češće pojavljuje na kartama Ugarske, nasuprot prostoru Bosne koji je bio pod Osmanlijama (Marković 1993, 234). I dok je zbog svoga položaja Slavonija postala posebno važna dijelu kartografa, istodobno je u kartografiranju pograničja došlo do snažnog razvojnog iskoraka prema većoj preciznosti zbog primjene geodezije. Širi se uporaba vojnih geodetskih izmjera, sve više se na topografskim kartama primjenjuju matematička znanja i mjerilo dok umjetnički elementi i dekoracija padaju u drugi plan. U usporedbi s nizozemskim kartografima, habsgurški su vojni inženjeri upravo u tim područjima kartografije bili puno iskusniji.

Slike Slavonije na nizozemskim kartama također su prilično ovisile o ukupnom kartografskom razvoju u Nizozemskoj. Gradovi na jugu poput Antwerpena zabilježili su zlatno doba svoga razvoja u 16. stoljeću jer su bili iznimno pogodni za djelovanje tiskara i nakladnika koji su oblikovali i objavljivali svoje publikacije za rastući broj znatiželjnih korisnika diljem Europe (Koeman i van Egmond 2007, 1290;Koeman i dr. 2007, 1298;Marković 1993, 134). Objava kvalitetnih karata različitih lokacija, uključujući i karte manje poznatih europskih zemalja, približila je prostor poznatoga Starog svijeta običnim ljudima (Koeman i dr. 2007, 1374). Nakon sedamnaestog stoljeća ekonomski i kulturni centri, kao i većina kartografskoga znanja prebacuju se u Amsterdam. Grad u to doba bilježi svoje najprosperitetnije razdoblje razvoja, zahvaljujući prvenstveno padu Antwerpena 1585. godine, koji je ponovno postao katoličko središte (Asaert 2004;Blom i Lambrechts 2014, 149-152;Zandvliet 1985, 38). Većina je obrazovanih (kalvinističkih) protestanata pristigla iz južnih krajeva Nizozemske i naselila se u Amsterdam, gdje se kartografska produkcija nastavila snažno razvijati tijekom sedamnaestog stoljeća. Koeman, Schilder i neki drugi istraživači razlog tom postupnom preuzimanju primata u kartografskoj industriji nalaze u činjenici da je Amsterdam bio bolja alternativa Antwerpenu zbog “trgovačkih putovanja i otkrića, rata protiv Španjolske, geografskih promjena unutar regije, ali i utjecaja useljenika iz južnih pokrajina” (Koeman i dr. 2007, 1299-1300, 1305).

Kao rezultat tih događaja su 16. i 17. stoljeće u povijesti kartografije poznati kao “stoljeće atlasa”, odnosno kao najproduktivnije i najvažnije razdoblje u razvoju umjetničke estetike po kojoj je nizozemska kartografska tradicija postala poznata. Tijekom osamnaestog stoljeća u nekim se slučajevima čak javlja zagušenost dekorativnog narativa pretjerivanjem, kićenom kaligrafijom ili prezastupljenom ornamenikom (Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017, 28). Od tog razdoblja novi akteri kartografske proizvodnje, poput Francuske ili Engleske, počinju dominirati europskim prostorom čime bitno otežavaju Nizozemskoj da zadrži primat i “monopol” na europskom tržištu role (Zandvliet 1985, 2, 93). Važnost vojnih karata, posebno za ratom zahvaćena područja poput jugoistočne Europe, nameće ih kao sve traženije proizvode. Svjedoči tome ukupna kartografska proizvodnja toga vremena (Fürst-Bjeliš i Zupanc 2007, 7-8, 11;Marković 1993, 234, 241;Marković 2005, 17;Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017, 51;Sills 2007, 981-1002, 991). Konačno, Mercator, Ortelius, Blaeu i još nekolicina bili su pioniri u prikazivanju hrvatskih zemalja na generalnim ili regionalnim ranonovovjekovnim kartama šesnaestog i sedamnaestog stoljeća. Oni su pak poseban značaj pridavali prezentacijama granica srednjovjekovnih kraljevstava na prostoru hrvatskih zemalja, među kojima je bila i Slavonija (Slukan, 2003: 115). Doprinos nizozemskih kartografa stvaranju percepcije o ranonovovjekovnoj Slavoniji i njezinom razumijevanju bitno je manje poznat istraživački problem. Neke su od njihovih karata osim toga bile pretisci ili dopune novim atlasima te su stoga u 17. i 18. stoljeću odražavale stanje i sintetizirale podatke iz prethodnih stoljeća

[5], dijelom i zbog skromnijih osobnih iskustava i mogućnosti prikupljana podataka njihovih autora (Fürst-Bjeliš i Zupanc 2007, 7-8;Mlinarić i Miletić-Drder 2017, 51). Slična se praksa može pronaći tijekom cijeloga ranog novog vijeka i u narativnim izvorima. Flamanski putnikvan Ghistele (1998) je primjerice putujući 1481. godine jasno naglasio da je Slavonija nekada davno bila Kraljevstvo, kojem su pripadale sve ostale zemlje, odnosno horonimi zemalja koje je za pripadajući prostor autor koristio, poput Dalmacije. S obzirom na to da je 18. stoljeće bilo kartografski vrlo plodno, posebno za prostore hrvatskih višestrukih pograničja, fokus je ovog istraživanja stavljen upravo na specifičnom nizozemskom kartografskom doprinosu poznavanja Slavonije.

3. Rasprava

Sve odabrane karte su međusobno uspoređene s obzirom na neke dominantne kartografske značajke, poput primjerice elemenata reljefa, hidrografskih elemenata, toponima, kao i oznaka razgraničenja ili fortifikacija.

3.1 Namjena karata i odnos između mjerila i sadržaja

Među nizozemskim kartografima bilo dosta sličnosti, premda i određenih razlika.Van Schagen (1729,slika 2),Ottens (1725,slika 4) ivan der Bruggen (1737,slika 3) su inicijalno odlučili posvetiti manje pažnje krajobrazu, odnosno prostornome reljefu. Planine su prikazane vrlo pojednostavljeno. Rijeke poput Drave i Save su također ucrtane relativno linearno, jednako kao i njihove pritoke. Može se to objasniti činjenicom da je u fokusu van Schagenove karte prije svega bila Ugarska, što potvrđuje i naslov karte. Premda se na prvi pogled van der Bruggenova karta dosta razlikuje od van Schagenove, prije svega zbog naglašenijih boja i užeg fokusa samo na Slavoniju, ona također manje pažnje posvećuje reljefnim značajkama. Brežuljkaste orografske formacije koje karakteriziraju današnju Slavoniju kod van Schagena su manje precizno prikazane ili su potpuno izostavljene. Područje današnje Srbije karakterizira istaknuta planinska dinamika, što je vjerojatno bila kartografska taktika za popunjavanje praznih prostora na karti koje je autoru bio od sekundarnog značenja za opću svrhu te karte. S razlikom od van Schagenove karte, van der Bruggen je na svojoj mnogo detaljnije ucrtao rijeke i ostale hidrografske elemente poput zavojitih pritoka. Uzrok tome počiva i u razlici mjerila, ali i u fokusu njegove karte, koji je u potpunosti bio usmjeren na Slavoniju. Najvažniji hidronimi zabilježeni su na latinskom jeziku, što potvrđuje trend upotrebe jezika za stjecanje prevlasti u kartografskoj proizvodnji. Osim toga,van der Bruggen (1737) je radio i prikupljao podatke u Pragu, Beču i Augsburgu te je stoga predstavljao austrijski, barem koliko i nizozemski kartografski pristup (vidjeti alternativnu inačicu iste karte u Felbar Collection, datiranu u 1740. godinu). Stoga je složen i promjenjiv kartografski identitet, odnosno refleksija osjećaja pripadanja, koji je vidljiv u njegovom radu, ujedno vodio zamagljivanju distinkcije između elemenata austrijskog, nizozemskog ili bilo kojeg drugog kartografskog pristupa ili tradicije (Slukan, 2003: 114;Black, 1997:10-12). S obzirom na to da su njihove karte prikazivale značajno veći prostorni obuhvat i bile drugačijeg mjerila,van Schagen (1729) iOttens (1725,slika 4) prikazali su vegetacijske i orografske elemente u znatno reduciranom i pojednostavljenom obliku.

Toponimi su na kartama uglavnom bilježeni latinskim jezikom, dok je više jezične “slobode” bilo pri bilježenju imena manje važnih naselja (ekonima ili ojkonima) ili riječnih pritoka (potamonima) (Faričić 2007, 148-179;Faričić i dr. 2012, 125-134).Van Keulenova karta (1716,slika 1) ima preciznije izrađen reljef, što se može objasniti izborom mjerila i svrhe karte. S druge strane oronime je na području Slavonije autor ponovno izostavio. Za razliku od ostalih Nizozemaca,Van Keulen (1716,slika 1) je više pažnje posvetio detaljima pošumljenosti prostora. Pritoci i najvažniji riječni tokovi su, kao i na nekim drugim nizozemskim kartama detaljno ucrtani, a njihova su imena zabilježena na latinskom jeziku, čime autor pridonosi međunarodnoj važnosti i prepoznatljivosti karte. Konačno, reljefni sadržaj nije bio posebno izražen niti na jednoj promatranoj nizozemskoj karti. S obzirom na to da je Slavonija ionako generalno nizinska zemlja, tek su manje važne (susjedne) regije strateški istaknute obojanim planinskim formacijama, što donekle implicira vertikalnu dinamiku tih prostora. Šumovita područja izostaju na kartografskim prikazima Slavonije, ali ih zato ima više na rubnom prostoru Ugarske, premda i tamo osamljeno raspršeno drveće pokraj rijeka služi popunjavanju praznina na karti. Rijeke poput Drave i Save su linearno pojednostavljene, dok su krivudavi meandri s pritokama nešto detaljniji. Premda su elementi reljefa na austrijskim kartama (Hommannovoj ili Reillyjevoj) donekle bolje elaborirani, niti na njima nema mnogo detalja. Osim toga, Reillijevi radovi s kraja stoljeća teško se mogu uspoređivati s nizozemskim kartama iz prve polovice stoljeća, i u umjetničkom i u raznom drugom pogledu. Uzrok tome su značajne promjene u zapadnoeuropskoj kartografiji koje su uslijedile upravo u drugom dijelu 18. stoljeća. Iskorak prema znanstveno utemeljenijoj kartografiji, temeljenoj na sustavnim geodetskim izmjerama dogodio se prije svega među habsburškim i francuskim kartografima, premda njihove odraze nalazimo i među nizozemskim autorima. Nažalost, nizozemske karte iz druge polovice 18. stoljeća su izuzetno slabo zastupljene i sačuvane u nacionalnim i privatnim kartografskim zbirkama koje smo konzultirali, stoga bi tu vrstu posebnih izvora odnosno kartografskih trendova na njima valjalo istražiti nekom drugom prilikom.

3.2 Kartografski utjecaji u primjeni toponima, boje i simbola

Upečatljivu novost karataGadee (1718),Schimeka (1788), posebno za prostor susjedne Bosne, iHomanna (1745) predstavlja obilje toponima, koji jasno ukazuju na široko znanje i bolje poznavanje regije, što kod Nizozemaca nije bio slučaj region (Slukan Altić 2003, 230). Tome svjedoči lijeva strana van Schagenove karte, na kojoj se istodobno nalaze naselja

Agram i

Zagrabia. Oba označavaju grad Zagreb, premda se

Zagrabia nalazi bliže današnjem Sisku (

Sisseg ili

Sisaken). Ova nenamjerna zabluda u kartografiranju hrvatskog prostora tako se stoljećima usvajala i širila među nizozemskim kartografima. I Mercator je uključio tu pogrešnu interpretaciju u svoju kartu. Taj podatak može objasniti zbog čega je i taj kartograf osamnaestog stoljeća još uvijek preuzimao inspiracije, ali i informacije sa starijih kartografskih predložaka (njemačkih i talijanskih). Neselektivno je precrtavao sadržaj s njih, što je uostalom tada bila uobičajena praksa. Premda van der Bruggen nije ponovio pogrešku s prikazivanjem Zagreba kao van Schagen, odlučio je istaknuti vjersku važnost Agrama pomoću odgovarajućih grafičkih simbola. Kao biskupsko sjedište,

Agram se izdvajao od ostalih gradova na karti, što je naglašeno vrlo prepoznatljivim simbolom križa na tornju gradske katedrale. Nasuprot spomenutom kopiranju zastarjelih podataka, habsburški je vojni kartografGadea (1718) zabilježio potpuno nove i točne pozicije čak 68 konkretnih, imenom označenih, graničnih humaka i zemljišnih oznaka koje su markirale liniju razgraničenja južno od Save, kao što je dogovoreno prilikom sklapanja Požarevačkog mira 1718. godine. Odredbe Mira su detaljno provedene i pažljivo zabilježene na kartama koje je za tu priliku izradila Komisija za razgraničenje. Ukupno gledano upravo su spomenuti mirovni ugovori predstavljali prekretnicu s obzirom na to da je njihova svrha i bila određivanje nove habsburško-osmanske granice. Konsolidacija teritorijalne cjelovitosti i suvereniteta, kao i širenje raznih ovlasti (upravnih, pravnih, političkih, vjerskih) vodili su uspostavi čvrste granice koja je ujedno bila nužna za rastući austrijski administrativni aparat (Black 1997: 17). Stoga je valjalo provesti detaljno kartiranje graničnoga prostora, koje je bitno pridonijelo napretku kvalitete geografskoga znanja o pograničnim dijelovima Slavonije, ali također i o ukupnoj geografiji uzduž linija razgraničenja.

Inspiracija i utjecaj “očeva kartografije” iz prethodnih stoljeća, posebno Mercatora, na osamnaestostoljetne nizozemske kartografe također se može primijetiti na van Schagenovoj karti, jer su današnje Nova Gradiška i Bosanska Gradiška zabilježene kao

Gradiskia i

Gradiskia Turcicum. Štoviše, istaknuta je važnost starih granica koje su postojale prije dolaska Osmanlija. Mir u Srijemskim Karlovcima (sklopljen 1699. godine) i Požarevački mir (sklopljen 1718. godine) označili su prekretnicu nakon koje su gotovo svi upitni prostori ponovno pripadali Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji (Fodor i Dávid 2000;Pešalj 2010, 29-42;Slukan-Altić 2003, 242;Tracy 2016, 5, 356). Van Schagenova karta objavljena je 1729. godine, u doba kada su Osmanlije uglavnom napustili područje oko Požege (

Posega) nakon poraza u bitci kod Slankamena 1691. godine (Slukan-Altić 2003, 140). Time se također potvrđuje postavka da se van Schagen kao nizozemski kartograf oslonio na starije karte. Sličan trend može se primijetiti na van der Bruggenovoj karti, posebno prilikom upotrebe „recikliranih“ toponima.

[6] Delislova francuska karta iz 1717. godine odražava izravan utjecaj i uvid u građu koji je imala Komisija za razgraničenje iz 1699. godine. Razlog leži u tome što jedan od suautora karte nije bio samo običan član Komisije kao specijalnog tijela već i njegov voditelj; grof Luigi Fernando Marsigli (Mlinarić i Miletić Drder 2017: 167-168).

Razlike su također vidljive u izboru i prikazivanju najvažnijih tvrđava u Slavoniji, bez obzira koriste li se pritom simboli ili boje.

[7] Po van Schagenu, Požega je imala važniju obrambenu ulogu kao tvrđava i tako se razlikovala od drugih gradova na njegovoj karti. Gradišku i Osijek (

Ezzech) su van Keulen, van Schagen i van der Bruggen prikazali tako da su naglasili njihov urbani, ali također i pogranični kontekst, ucrtavajući svega nekoliko tornjeva. Za razliku od van Schagena, van der Bruggen je crvenom bojom naznačio utvrđene Osijek (

Eszek), Slavonski Brod (

Brod), Ilok (

Illok) i Varaždin (

Varasdin). Požega (

Posega) je donekle bila u drugom planu, iako je njezino ime upisano istom veličinom slova. Razlog da su navedeni gradovi naglašeni crvenom bojom i na van der Bruggenovoj karti bio je u njihovom istaknutom položaju na granicama te u strateškom i vojnom značaju. Ivanić Grad (

Ivanitz), Kraljeva Velika (

Kraliovavelika) i Nova Gradiška (

Gradiscia) su također prikazani detaljnim utvrdama, premda nisu naglašeni crvenom bojom. Nadalje, Slavonski Brod ima dvojako označene fortifikacije; i crvenom bojom i bez obojenja, što označava njegov složen i strateški važan, ali donekle i ambivalenatan položaj. Austrijski kartografi primjenjuju slične obrasce u prikazivanju fortifikacija kao i Nizozemci. Crvenu boju i simbole utvrđene arhitekture (kule) se inače koristilo u prikazima za većinu većih i vojno značajnih pograničnih naselja. Neke od fortifikacija su na nizozemskim kartama jasno označene simbolima križeva, čime je naglašena njihova pripadnost kršćanskom prostoru. Van Keulen je isti obrazac primijenio na svojoj karti. S druge strane na ovom specifičnom primjerku karte ne može se pronaći utvrde označene polumjesecom na prostoru s druge strane jasno bojom istaknutih granica. Dobar primjer spomenute identifikacije političkog suvereniteta simbolima može se pronaći na karti talijanskog autora Pagana

Tvto il Côtado di Zara e Sebenicho iz 1530. godine. On je jednoznačno zabilježio razliku između osmanskih i kršćanskih posjeda u Dalmaciji upotrebom stijegova s polumjesecom na istaknutim utvrdama osmanlijskog pograničja (

serhat). Isti princip razgraničenja povlačenjem konkretne granične linije, ali i dosljednim razlikovanjem prostora upotrebom kartografskih simbola identiteta (križ za kršćanska, tj. mletačka naselja i polumjesec za muslimanska tj. osmanska) još je jasnije vidljiv na nizozemskoj karti sjeverne DalmacijeJana Janssoniusa (1646).

Poput van der Bruggena, van Keulen je također odlučio koristiti boju, uglavnom za distinkciju različitih teritorija. Osijek (

Essek), Ilok (

Ilock ili

Vylakv), Petrovaradin (

Peter Warden) i većina drugih gradova manje važnosti označeni su crvenom bojom, ne bi li se, kao i kod van der Bruggena naglasio njihov strateški važan pogranični položaj. Doduše, Osijek se razlikovao od drugih gradova zbog van Schagenovog dodatka riječi

Ezzech brug (i van Keulenovog

Essecker Brück, pisano njemačkim pismom), pri čemu nizozemska riječ

brug znači most. Zanimljivo je da je drveni most, koji je Mimar Sinan gradio za Sulejmana, izgorio 1686. godine, što potvrđuje da su oba Nizozemca bili vođeni starim materijalima te su bilježili određene povijesne karakteristike regije iz vremena osmanske uprave (Haničar Buljan i dr. 2014). Naime, spomenuti je most bio od velike važnosti upravo tijekom osmanske vladavine te su ga stoga putnici iz zapadne Europe nerijetko spominjali. Englez Edward Brown je drveni most čak vizualno prikazao u svom putopisu iz 1673. godine (Brown 1673). Još jedan prikaz mosta izradio je flamanski slikar iz sedamnaestog stoljeća. U knjizi koja prikazuje gradove Austrije, antwerpenski barokni umjetnik Jacob Peeters, nacrtao je

Essekker Brugh na uvodnoj stranici poglavlja o gradovima Donje Ugarske (Peeters 1690).

Toponimi korišteni za područje Slavonije jasno upućuju na nadahnuće radovima njemačkih i mađarskih kartografa, a primijenjen je i lagani zaokret prema većoj uporabi nizozemskog jezika. Korištenje riječi poput "brug" i načina na koji su napisani

Posega i

Sisaken ukazuju na očekivani utjecaj nizozemskog jezika u nizozemskoj kartografskoj produkciji. Gerard van Keulen je čak kombinirao francuski i nizozemski jezik tako što je Virovitičku i Srijemsku županiju nazvao

Comte de Walpon of [što na nizozemskom znači "ili"]

de Walkon. Manje pritoke kao što su

Krasiza of [“ili” na nizozemskom]

Gasso Flu ili

Draw als Trah Flu. potvrđuju primjenu nizozemskog jezika. Za važna mjesta korišteni su nizozemski toponimi. Primjer je tadašnji ugarski grad Pečuh na karti zabilježen kao

Quinque Ecclesiae als Vyff Kerken o[f]

t Ote Oiazak, što predstavlja kombinaciju latinskog i nizozemskog jezika. Promatrajući nizozemske naslove karata, zamjetno je da je van Schagen uključio riječ za rat (

Oorlog), a odnosi se na ratnu klimu na osmanskom pograničju. Jednako kao i na samoj karti, Gerard van Keulen je i u naslovu tekstualno opisao Slavoniju kao dio veće cjeline. Korištenjem riječi

Batalje u naslovu karte, a koja u nizozemski dolazi od iskrivljene francuske riječ za bitku (

Bataille), autor ponovno naglašava vojni aspekt i svrhu oba zemljovida.

Ono po čemu se austrijske karte komparativno razlikuju od nizozemskih uglavnom je precizniji fokus na prostorni prikaz, granice i detalje koji su imali za cilj naglasiti vojnu svrhu. Granica je povučena tako da obuhvati čitavu regiju Srijema između Save i Dunava kao posjed Slavonije. Prikaz graničnog razgraničenja i specifičan izbor boje učinili je kartu iznimnom. Takav prikaz implicirao je geostratešku realnost, jer je jugoistočni dio Srijema bio u osmanskom posjedu do kraja habsburško-osmanskog rata 1716-1718 (Mlinarić i Miletić Drder 2017, 194). Isprekidane linije zapravo su označavale teritorij Vojne krajine ili

Militär Gränze kako ju je nazvao Reilly. Druga točkasta crta označava stvarnu granicu koja je nastala nakon Požarevačkog mira 1718. godine. Znakovite su i neke druge Reilllyjeve linije koje se nisu mogle naći niti na jednoj drugoj karti. Jedna od njih počinje od Zemuna (

Semlin) i nastavlja sve do Novske (

Nofska), s s drugim krakom prema Osijeku (

Essek) i Požegi (

Possega). Te linije i točke koje ona povezuje su različita gradska naselja u Slavoniji koje povezuju poštanske rute (Mlinarić i Miletić Drder 2017, 194). Navedene značajke rijetko su se javljale na kartama iz ranijih razdoblja i također ukazuju na promjenu stila izrade utilitarnih karata. Konačno, zanimljivo je kako jeReilly (1791) zabilježio područje regije

Kleine Walachey oko rijeke Pakre (

Parka Fl.). Ona se pojavljuje samo naDelisleovoj karti iz 1717., na kojoj su zabilježene i stare županije, a sve je bilo omogućeno direktnim Marsiglijevim informacijama. Prema Ankici Pandžić, horonim

Kleine Walachey ili

Mala Vlaška se često može pronaći na „granici između banske Hrvatske i turske Slavonije, oko Pakraca“, a odnosi se na vlaška naselja iz 15. i 16. stoljeća koja su imala obavezu „braniti granicu od Turaka. (...) Iako se to područje četrdesetih godina 18. stoljeća vraća županijskoj upravi, odnosno civilnoj Hrvatskoj, naziv Mala Vlaška zadržao se na kartama do kraja 18. stoljeća (Pandžić 2005, 60). Osim toga, naReilleyjevoj poštanskoj karti (1791) zabilježen je novi element poštanskih ruta i postaja, koji prati potrebe rastućeg austrijskog administrativnog aparata s kraja osamnaestog stoljeća (Slukan-Altić 2003; 230).

Premda je prikazivao gotovo isti opseg Slavonije, Homann je na svojoj karti uz latinski istaknuo i francuski prijevod naslova. Karta je također obojena i uređena točkastim linijama teritorijalne podjele. Ocrtala je granicu između Slavonije kao dijela Habsburškog Carstva i Bosne kao dijela Osmanskog Carstva nakon sklapanja Požarevačkog mira. Osim toga, upečatljivo je da je Homann odlučio crvenom bojom istaknuti staro razgraničenje, kakvo je vrijedilo prije sklapanja mirovnog ugovora 1718. godine, što potvrđuje da se oslanjao na karte svojih prethodnika. Stoga također ne čudi što se Homann izdvaja od ostalih analiziranih kartografa time što prikazuje raspored i smještaj ranijih vlastelinskih posjeda, kao prostor

Dominija (

Dominium). Oni se mogu čak i međusobno razlikovati jer su odvojeni točkastim linijama (Mlinarić i Miletić Drder 2017, 176-177). Kao što je već spomenuto, razgraničenja sukladna zaključcima mirovnih ugovora dominantno su obilježavala kartografsku produkciju austrijskih i njemačkih kartografa, kao što je bio slučaj saSchreiberovom kartom (1749) i potkraj stoljećaSchimekovom kartom (1788).

3.3 Upotreba grafičkih dekoracija i/ili kartuša