Introduction

Today, women’s participation in sports shows positive signals. At the international level, this is illustrated by a record of 48.7% of women participating in the Summer Olympics in Tokyo 2020.2 In parallel, we observe that more and more sports traditionally perceived as male-dominated, such as American football, hire women in coaching functions. A similar observation applies to the presence of women in the decision-making positions of sport organisations. We see, for instance, an encouraging evolution in the percentage of women members of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) from 21% to 38% between 2013 and 2020.3 Nevertheless, current studies and data concur to confirm that gender equity in the decision-making positions of sport organisations is still an issue, as women are still and largely underrepresented compared to men.4,5,6,7,8

In the Swiss sport system, public intervention in the non-profit sector is based on the principle of subsidiarity9. Sport organisations in this sector, such as Swiss national sports federations (SNSF), sport clubs, or the umbrella association of sports (Swiss Olympic), benefit from an important degree of strategic and operational autonomy. However, they also benefit from direct and indirect financial support by the public sector at the three levels of Swiss federalism (federation, cantons, and municipalities). They receive subsidies for their contribution to the development of elite or mass sport and can have facilitated access to sport facilities. Swiss Olympic represents the interests of more than 80 SNSF and partner organisations, and organises the Olympic teams. It mainly relies on public support anchored in time-bound performance agreements with the Federal Office of Sport (FOSPO) – that is part of the Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) – as well as from lottery funds. At the national level, we observe that the percentage of women presidents in SNSF and Swiss Olympic stagnated at around 5% for the period between 2000 and 2009.10 In the following years, the representation of women in the presidencies of SNSF recorded an increase and, according to Markus Lamprecht, Rahel Bürgi, Angela Gebert, and Hanspeter Stamm11, came to around 20% in 2016. In 2019, the sample of heads of performance surveyed in the study by Hippolyt Kempf et al.12 consisted of only 21% women. In 2021, only 14.7%13 of the heads of lower management units of the FOSPO and 30.7%14 at Swiss Olympic were women. At the local level, of the 20,000 voluntary sport clubs that compose the non-profit sector, membership is largely male-dominated. Only 18% of these organisations are headed by female presidents.15 Gender underrepresentation in the decision-making positions of the main sport organisations in the public and non-profit sectors in Switzerland is a clue, and this evidence confirms a strong consensus in the literature and other levels of analysis that gender underrepresentation is the norm rather than the exception.16

Research that combines gender dynamics and sport governance is not recent.17 The representation and promotion of women in sport organisations is a traditional sport governance theme that is developing as a result of the desire of sport governing bodies,18 such as umbrella associations (national Olympic committees [NOCs] and/or association of sports federations) or sport ministries to diversify, democratise, and make more equitable decision-making of sport organisations that are largely dominated by men.19 Since the early 2000, this organisational deficit has led to an important body of context-sensitive literature that investigates the micro (individual), meso (organisational), or macro (systemic) measures to be activated to improve the presence of women in decision-making positions.20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 The literature highlights the influence and steering role of sport governing bodies and discusses the effectiveness of “hard” (e.g. binding quotas and targets) versus “soft” (e.g. awareness-rising) measures.31

In contrast to other European countries, such as Norway, and compared to measures in the areas of sports facilities, sport ethics and security or the promotion of elite and mass sport, we observe that gender equity from a macro perspective has not been a priority until recently. However, the discourse on the need to increase the number of women in decision-making positions of sport organisations has taken on a new dimension since 2019, with the accession of the first woman to head the DDPS since its creation in 1998. This has energised institutional discourse and narratives on the ineffectiveness of gender equity policies in sport and led to the implementation of harder measures to ensure better representation of women in the army32 and in decision-making positions of SNSF, including a target requirement of a minimum of 40% representation in executive committees to be implemented by the end of 2024.33,34

Building on sport governance literature and existing longitudinal case studies, the objective of this contribution is to uncover the evolution of gender representation in decision-making positions in sport governing bodies in Switzerland and to identify the relations with associated measures. With a quantitative analysis, we analyse the three important organisations in the Swiss sport system from the public and non-profit sectors – (a) the FOSPO, (b) Swiss Olympic and (c) SNSF – that are not covered by current statistical databases on sport and gender from the European Institute for Gender Equality and focus on three levels of decision-making.35 The analysis covers the period between 2012 and 2021, which concurs with both the enforcement of the Sports Promotion Act and the available raw data Kempf et al.36. The first section of this paper highlights the evolution of gender representation in the decision-making of sport organisations at international and national levels and reviews the existing measures to promote gender equity. We include an overview of the initiatives undertaken in the Swiss sport system. The research design and data collection strategy are presented in the second section. We analyse (a) the evolution of women's representation in decision-making positions in national sports federations in Switzerland over a 10-year period (2012-2021) and (b) compare the observed evolution with the implementation of hard and soft measures.

Many sports and disciplines have gradually become more feminised since the beginning of the 20th century (more women’s competitions and women’s clubs). The participation of athletes in the 2020 Summer Olympic Games in Tokyo is close to perfect equality, with 48.7% of women participating.37 Boosted by targeted programmes, such as the Alpine’s Rac(H)er Programme38 or National Football League’s diversity policy to hire female offensive assistant coaches, the presence and performance of women in traditionally male-dominated sports and functions (car racing, football refereeing and men’s basketball coaching) is increasing. From an economic perspective, a handful of sports offer encouraging examples of commercialisation and growing fan interest. However, the figures are still far from the revenues generated by men’s competitions. In addition, although female athletes can earn more than their male counterparts (e.g., in tennis), the most paid athletes in the sports industry are men at the international level. In the Swiss sports system, this applies especially to ice hockey and soccer.39 In a similar way, their representation in decision-making functions at the governance and management levels is still mainly dominated by men. At the international level, while we see an encouraging increase in the percentage of women IOC members40 between 2013 and 2020 from 21% to 38%41, the issue was set on the agenda twenty years earlier, in 2000, as part of the IOC reform following the Salt Lake City scandal.42 In 2010, only 18% of the members of the executive committees of international sports federations were women.43 This trend has rarely moved six years later, as in 2016, the level of representation barely exceeded 15%.44,45 In 2020, only one of the 28 international summer sports federations has a board with a gender representation of more than 40%.46 At the national level, the number of women on the executive committees of the French NSF has also steadily grown. After a stagnation between 2009 and 2013, their representation increased between 2013 and 201747; however, the figures navigated around 35% for Olympic and 30% for non-Olympic NSF. In 2013, only 12% of the executive committee members of the Spanish NSF were women, and this figure rose to 25% in 2018. However, this proportion is much lower for the highest position in decision-making (approx. 5%).48 This evidence also confirms a trend identified in other countries, as the presence of women in decision-making in NSF of the 28 countries of the European Union (EU) represented – in 2017 – only 14% of all the functions and only 5% for the function of president.49 Between 2007 and 2020, women’s representation in the decision-making functions of the NSF of Liechtenstein stagnated and could not exceed 18%.50 In 2010, only 17.6% of the executive members of NOCs were women.51 In 2016, this figure barely exceeded 15%.52 Although there is a slight positive evolution for the position of president and deputy president, we find evidence that the number of women at the highest executive position of NOCs in the 28 EU countries even decreased from 14.3% to 11.1% between 2019 and 2022.53 In the public sector, available data from the European Institute for Gender Equality do not allow us to identify a clear longitudinal trend among national sports ministries, but we observe that women are comparatively better represented at the administrator level than at the minister level, particularly senior administrators (49.7% in 2022). Although evidence shows global and perceptible improvements in gender representation in the decision-making positions of sport organisations, the situation is still problematic.54 While several measures have been implemented to correct gender inequalities, we observe that in some national contexts, the situation has barely changed, and overall, men remain overrepresented, especially in the highest decision-making positions.

MEASURES TO IMPROVE GENDER REPRESENTATION

Studies that combine sport governance perspectives and the question of women’s representation and promotion in sport organisations are not recent.55 There are mainly interested in making these more diversified, democratic, and equitable, as these are still and largely dominated by men.56 Gender equity is about ‘achieving democratic legitimacy.’57 This domination is considered a constraint that can hamper fairness and social justice values58 and reinforce the “glass wall” effect for women who seek career advancement,59 as well as the expected positive influence on the performance and “good” governance of sport organisations.60,61 This deficit has led to an important body of literature on the micro- (individual), meso- (organisational) or macro-level (systemic) measures to be activated and implemented to make sport organisations more equitable62,63,64,65, including a fruitful debate on the effectiveness of “hard” (e.g. regulation or sanction) versus “soft” (e.g. informal communication) ones.66,67 In this vein, Hovden68 shows, in particular, that the introduction of quotas is not the principal driver when considering the overall distribution of men and women in decision-making positions, but it can secure the nomination of women, as requested by related regulations. Building on studies by Burton and Leberman69, Table 1 illustrates potential measures to promote gender representation in sport organisations.

Table 1: Measures to promote gender representation in sport organisations

| Measures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hard | Soft | |

|

Micro-level (individual/personal) | ||

|

Meso-level (organisational) | ||

|

Macro-level (systemic) |

Source: own illustration.

Micro-level measures focus on the transformation of individual behaviour as a key driver to activate and initiate change within an organisation. Relevant studies build on the assumption that women are often not equipped with the necessary psychosocial predispositions to pursue a career in decision-making positions (e.g. character, confidence, values, perceptions, capital, or beliefs) or that their role can be influenced by the resistance of their (male) peers,70,71 which, in turn, influences their attainment and retainment in decision-making positions.72 To unlock such situations, targeted measures are oriented on confidence, motivation-building, and empowerment, including tailor-made mentoring or leadership development programmes, but also on gender-friendly communication (e.g. inclusive writing) and individual lobbying for decision-making positions. In this regard, women leaders and managers play a key role in implementing gender equity measures.73 Their roles in allocating resources, promoting employees, shaping organisational strategy and culture, and implementing concrete measures are key.74

At the meso-level, barriers to gender representation are mainly found in negative workplace culture,75 the lack of strategy and capacity of organisations to set and implement gender-promotive cultural settings or organisational values,76,77,78 organisational policies or processes, such as selection procedure and informal recruiting processes,79,80,81 or the influence of dominant leadership discourses and perceptions of gender-oriented skills within an organisation.82 Typical hard measures to lift this burden include dedicated strategies (i.e. inclusion of gender promotion in the strategic objectives or the strategic plan), positive discrimination recruiting, and hiring or equal salary policies. Softer measures include the development of gender-promotive organisational values or the organisation of conferences and events on the topic.

At the macro level, barriers to gender representation in decision-making positions are mainly found in the ineffectiveness of sport governing bodies to steer the behaviour of organisations in the sport system to be consistent with desired outcomes by pressure, incentives, regulation, or control.83 Such organisations play a particular role, as they can change the status quo and balance gender injustice through equitable recognition and redistribution.84 Typical macro-level and hard measures include the implementation of gender quotas and targets by regulation,85 as well as binding governance codes, as illustrated by the introduction of Sport England and UK Sport’s code for sports governance.86 Several context-sensitive analyses have been performed on the impact and effectiveness of quotas or targets87 for national sport organisations, such as in Australia88, France89, the United Kingdom90, Norway,91,92,93,94,95 Sweden,96 or Spain97.98 Evidence highlights that quotas and targets have a positive impact on the representation of women in decision-making bodies and that the figures tend to rise after regulations are implemented. Adriaanse, and Schofield99 found evidence in Australian sport organisations that boards with a minimum of three women represented are perceived as a precondition to advancing gender equity. In Spain, the figures in NSF have increased from 12% in 2013, the year before the implementation of the quota, to 25% in 2018. Similar findings are found in France between 2009 and 2020.100 Hovden argues for “fast-track” gender quota implementation instead of a more incremental approach, as it can serve as political legitimation to growing stakeholder impatience and fatigue for advancing gender equity in sport organisations for decades.101 From a soft perspective, initiatives to increase and support the involvement of women in sports in all functions and roles have been introduced one after the other from the mid-1990s, with the organisation of IOC’s World Conferences on Women and Sport since 1994, the creation of International Working Group on Women and Sport (1995), the signing of the IOC supported Brighton Declaration (1994) and the report by the IOC 2000 Commission published in the aftermath of the Salt Lake City Scandal in 1998 that insists on equal representation of men and women members IOC bodies, such as the Athletes’ Commission and the Brighton plus Helsinki Declaration on Women and Sport (2014), whose main tenet is that ‘without women leaders, decision makers and role models and gender- sensitive boards and management with women and men within sport and physical activity, equal opportunities for women and girls will not be achieved’.102 Such soft initiatives remain present today, as many good governance benchmark analyses, such as the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations Reviews of International Federation Governance (Indicator 3.8) or the Sports Governance Observer (Principles 24 and 50), include gender-targeted measures, a path initiated by the Sydney Scoreboard in 2016. Such soft measures are key ‘in creating awareness of and sensitivity to the issue’103 of the equal representation of women and men in the governance of sport governing bodies.

MACRO-LEVEL MEASURES TO PROMOTE GENDER EQUITY IN THE SWISS SPORT SYSTEM

Between the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Swiss sport system underwent several structural changes that formed the foundations of what is still relevant today. The Swiss Sports Association and the Swiss Olympic Committee merged to form Swiss Olympic, and the Federal Military Department was expanded to include the area of sports, including the creation of FOSPO. Pertaining the division of competencies that is characteristic of a federalist system and the principle of the subsidiarity of public intervention, non-profit sport organisations, such as NSF, benefit from an important degree of strategic and operational autonomy. However, they can also rely on direct and indirect financial support by the public sector at three levels of Swiss federalism: national, cantonal, and local. They receive subsidies for their contributions to elite and mass sports and can have facilitated access to sport facilities. Today, Swiss Olympic represents the interests of more than 80 NSF and partner organisations, and also mainly relies on public funds from lotteries based on time-bound performance agreements with FOSPO. Swiss Olympic and FOSPO also cooperate with numerous actors in the Swiss sport system, particularly when amending laws and ordinances, concluding service agreements, or issuing standards with NSF. This configuration leads to a significant production of interpellations, motions, and concepts in many areas of sport.104

At the macro level, the topic of gender representation in the decision-making positions of sport governing bodies emerged at the beginning of 2002, when the Federal Council’s (2000) concept for a sports policy in Switzerland recognises that ‘the proportion of women in leadership positions (...) is still too low’ (p. 6) and that it is necessary to put in place measures to encourage their participation. In 2002, this concept led to a catalogue of measures, which was successively evaluated for the period 2003–2006 and 2007–2010. However, the evaluation did not mention any references to the targeted measures. During this period, neither the law or the ordinance on sport, nor the service agreement between FOSPO and Swiss Olympic made any reference to measures on the promotion of women. Since 2006, Swiss Olympic requires its member federations to allocate at least 15% of the federal subsidies to the promotion of ethics in sport on the basis of the seven principles of the 2004 FOSPO/Swiss Olympic Charter on Ethics in Sport, of which equal treatment is a key principle. However, the principle does not specifically mention gender representation. We observe, however, that the Swiss Sports Observatory gathers information and monitors its evolution – not in the area of “fairer and safer sport,” but in the basic dataset.

The 2010s coincided with the first steps of the revision of the Sports Act and a period marked by the fight against organisational corruption in sport. While the fight against doping was already included in the 1972 law, ethics and safety in sports were given an entire chapter in the new draft (Chapter 5). The Charter of Ethics in Sport was revised, and three new specific concepts and measures in the field of mass sport, youth sport, and elite sport and sports facilities were published. Similar to 2000, the federal government’s concept for youth and elite sport (only) acknowledges that targeted measures have been taken by clubs and NSF without mentioning concrete examples, but again regrets that women are proportionately less numerous than men in youth and elite sport and significantly underrepresented in decision-making positions in Swiss sport at a historically very low level (Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS 2016). This leads the federal government to call NSF for better promotion, but only from 2024 onwards. Between 2010 and 2018, the strategies of Swiss Olympic adopted and published in 2012 and 2015 or the performance agreements between the FOSPO and Swiss Olympic (2011–2014, 2014–2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019) make no reference to the promotion of women in decision-making positions. As an administrative unit of the federal government, the FOSPO is directly influenced by policymaking in the field of human resources. Based on the Federal Personnel Act (SR 172.220.1), employers must take appropriate measures to ensure equity between women and men. With strategic target values, the federal government sets target values for the proportion of women in the administration.105 For many years, the FOSPO has been below the target value of 44–48% of women in decision-making positions for 2016–2019 and 46–50% for 2020–2023.106

We observe that the discourse on the need to increase the number of women in decision-making positions has taken on a new dimension in 2019, following the accession of the first woman to head the DDPS since its creation in 1998. This has energised institutional and political narratives on the ineffectiveness of gender equity measures in parliament (see Inquiry Trede) and in the federal government, which has led to the implementation of harder measures to ensure better representation of women in decision-making positions. Building on its strategy of 25 November, 2020 for companies linked to the Confederation, the federal government expects the NSF to comply with gender representation targets (Federal Council 2021a). This includes a target requirement of a minimum of 40% of women’s representation in executive committees to be implemented by the end of 2024.107,108 The performance agreement between FOSPO and Swiss Olympic obliges NSF to promote gender equity. In the version of 2021, Swiss Olympic shall set related measures and is also requested to document the progress made on the basis of the performance agreements with NSF. In the medium term, gender equality measures will be integrated into the revision of the Sports Promotion Ordinance, and compliance with the targets should be taken into account in the calculation of subsidies.109 Ultimately, the federal government considers that Swiss Olympic is responsible for conducting awareness-raising and education campaigns but, currently, without related financial support.110 In April 2021, the federal government issued Equality Strategy 2030 as the first national strategy to specifically promote gender equity. It sets four action fields (professional and public life, conciliation and family, gender violence, and discrimination) and related goals and measures, particularly related to the improvement of gender representation and gender balance in decision-making positions. This representation should be implemented in particular in events, conferences, and panels by or with the federal administration.111

Another special situation occurred at the meso level at the time examined, with a stronger impact on the advancement of women. “The Magglingen Protocols” is the name given by the media to revelations by eight Swiss female athletes about abuse in gymnastics training at the national sports centre in Magglingen. The documents became public at the end of October 2020 and have been processed in the media and politically since. As a result, the federal government wants to put ethical principles into sports on a legally binding basis. In this way, the federal government can enforce financial cuts if the principles are not adhered to. The ethical principles will be anchored in an amendment to the Sports Promotion Ordinance (SR 425.01), which is due to come into force in 2023.112 This amendment includes a balanced gender representation in the management bodies of sports organisations (association board, foundation board and board of directors) being required as a prerequisite for the disbursement of financial support.113 Gender balance is achieved when both genders are represented by at least 40% of the seats in a multimember body.114 In addition, because the required integration of ethical principles in the Sports Promotion Ordinance is based on the Sport Promotion Act (SR 415.0), these adjustments would have a long-term character.

Ultimately, as it was at the international level, the prevalence of the topic has been reinforced since 2020 – by the creation of specialised organisations, such as Helvetia on Track or Sporti(f) – to improve the visibility and recognition of women in all areas of sport and to ensure that clubs, federations, public authorities, and other sports organisations are involved in its process and public authorities and other sports organisations balance the composition of their bodies, commissions, juries, boards of directors, managements, and management teams.115 Within this context, measures include benchmark analysis and the ongoing development of a database that includes a list of women leaders in sports. It also includes awareness-raising campaigns. Sporti(f) organises networking events, and Helvetia on Track requests that decision-making positions are publicly communicated, that the criteria are set, and that sport governing bodies, such as Swiss Olympic, shall submit at least one female and one male candidate for each candidacy. In 2020, Swiss Olympic organised the first “Swiss Olympic dialogue” on the topic of women in decision-making functions. In the last two years, several NSFs, such as the Swiss national football association, have also decided to raise awareness on the topic with debates and conferences. Such softer measures are also perceptible with regular political speeches or interviews with Federal Councillor Amherd including calls for more women in sport governing bodies or a better promotion of women.116,117,118

Methods

To provide evidence in response to the research question, a descriptive analysis of the quantitative data was conducted. The analysis period covers 2012–2021, as the Federal Act on the Promotion of Sport and Exercise (SR 415.0) was passed in 2012; this act represents a landmark in Swiss sports policy and therefore provides the legal basis for the national promotion and financial support of sports. The Sports Promotion Act counts among the hard measures at the macro level (see Table 1).

Figure 1. Study Design

Notes: FOSPO = Federal Office of Sport; SNSF = Swiss National Sports Federations. Source: own illustration.

The quantitative data collection and analysis measures the variation in women’s representation in decision-making positions in sport governing bodies. Three different organisations were considered that act on a national level: (a) the FOSPO, (b) Swiss Olympic and (c) SNSF. The FOSPO represents the public sector, while Swiss Olympic and the SNSF represent the non-profit sector. For all three organisations, gender representation in operational decision-making positions was analysed.

At the FOSPO and Swiss Olympic, decision-making positions were defined if the persons worked in a management function according to their employment contract. Within these two organisations, the lower, middle, and higher managements were examined in an aggregated manner since no information on the level of the management position was available in the data set. The data on the proportion of women at FOSPO were supplied directly by FOPER as percentages over the years 2012 to 2021.119 No data on absolute figures for the FOSPO were available. The data set for Swiss Olympic was supplied by Swiss Olympic itself over the entire period from 2012 to 2021.120 The data set contained absolute numbers of women and men over the specified period with a sampling size varying between n = 16 and 25 depending on the year. At the SNSF, leadership positions were defined according to their function, with the underlying idea of examining the superiors of athletes in elite sports. Therefore, performance directors and youth sport directors were examined, as they act as supervisors of athletes in elite sports. Those positions can be assigned to lower management without an existing definition by the SNSF respectively. The data was provided by Swiss Olympic and originates from a database extract as of 25.02.2022 of the functions performance directors and youth sports directors with a varying sample size of n = 74 to 88 from 34 SNSF representing 55 different sports over the period between 2016 and 2021. Since the functions were not systematically recorded before 2016, there is no data available for the previous years.

Results

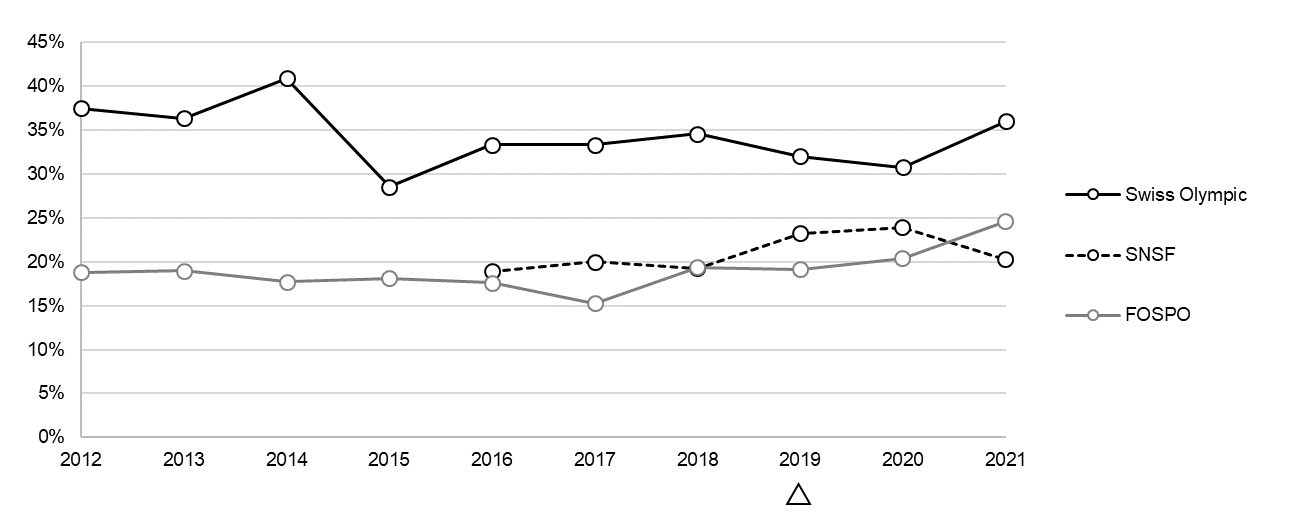

The quantitative data analysis examined whether the proportion of women in leadership positions changed between 2012 and 2021. Looking at the gender representation in decision-making positions in the three different sport governing bodies (Figure 2), it is apparent that Swiss Olympic has the highest proportion of women overall. In all three organisations, there is fluctuation in women’s representation, and therefore no trend identifiable towards more women over the entire period from 2012 to 2021. The FOSPO has shown an upward trend since 2018, with a slightly stronger increase from 2020 to 2021. This increase is also identifiable at Swiss Olympic. In contrast, SNSF showed a decline in 2021 after an increase in the proportion of women in previous years.

Figure 2. Proportion of women in operational leadership positions of Swiss sport governing bodies 2012–2021

Notes: FOSPO = Federal Office of Sport; SNSF = Swiss National Sports Federations; = Taking office of Federal Councillor Viola Amherd. Source: FOPER, Frauenanteil im Kader des Bundesamts für Sport und der Bundesverwaltung; Swiss Olympic, Gender-Statistik; Swiss Olympic, “Card-Inhaber (Swiss Olympic Techniker)” [dataset], accessed February 25, 2022, https://www.swissolympic.ch/athleten-trainer/swiss-olympic-card/card-inhaber.html?searchId=7971).

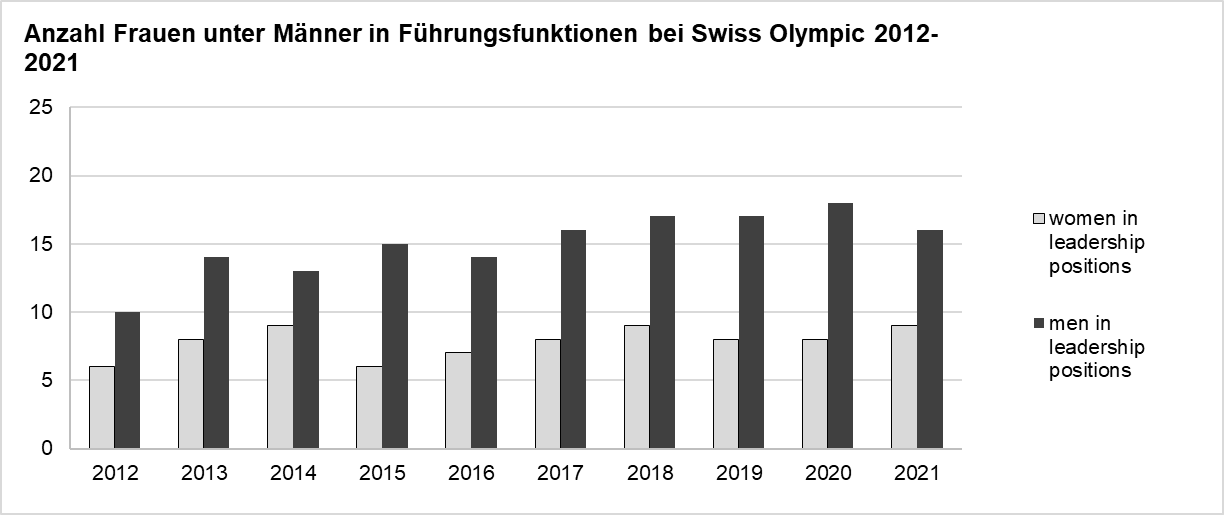

Figure 3 shows the absolute number of women and men at Swiss Olympic over time. It is evident that the proportion of women fluctuated over the entire period and that the proportion of women in 2021, at 36%, was very slightly below the baseline level of 2012, at 37.5%. In 2015, there was a drop in the proportion of women caused by an increase in the number of men, accompanied by a reduction in the number of women. Since then, the proportion of women has fluctuated, never returning to its peak level in 2014 (41% of women). The increase in women’s representation in 2021 can be explained by an increase in women and a decrease in men at the same time. Consequently, no pattern can be identified as to whether the gender distribution is more likely due to a change in the proportion of women or to a change in the proportion of men. However, it can be seen that when large changes in the gender distribution occurred, this was due to an opposite development in the two gender ratios.

Figure 3. Number of women and men in management positions at Swiss Olympic 2012–2021

Notes: Source: Swiss Olympic, Gender-Statistik

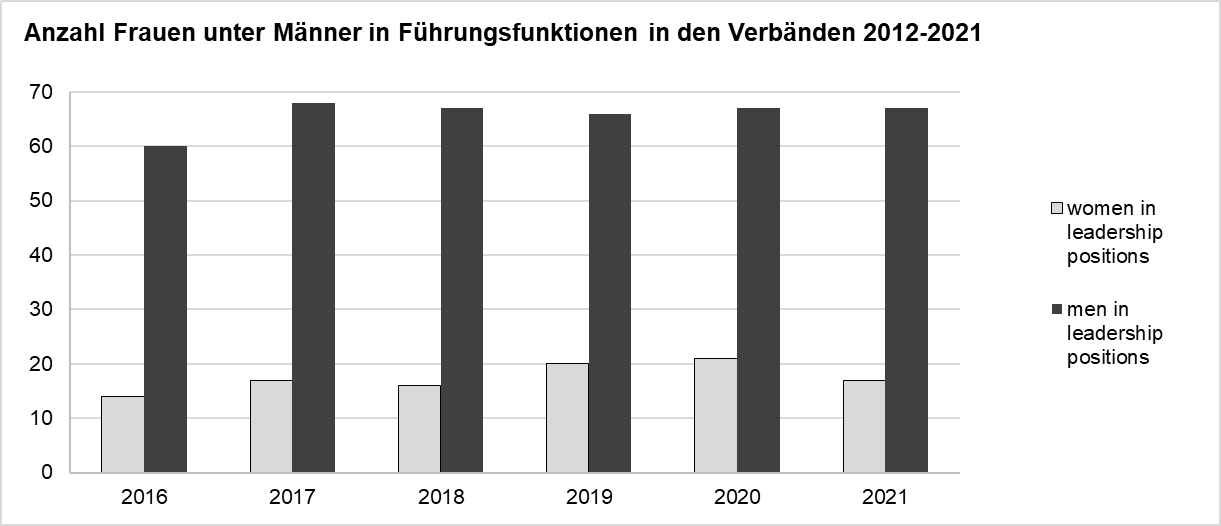

The absolute number of women and men at the SNSF over time is shown in Figure 4. Similar to Swiss Olympic, the SNSF do not show clear patterns in gender distribution, but rather fluctuations among women, as well as men.

Figure 4. Number of women and men in leadership positions at SNSF 2016–2021

Notes: Source: Swiss Olympic, “Card-Inhaber (Swiss Olympic Techniker)”

Discussion

The aim of this study was to present the evolution of gender representation in sport governing bodies in Switzerland in light of three cases: FOSPO, Swiss Olympic, and SNSF. During the period 2012 and 2021, evidence from our data shows that (a) there is no overall positive trend in the representation of women in decision-making positions in the three examined organisations and (b) that compared to other national contexts, figures are relatively low for national sport governing bodies and FOSPO (15.3% to 24.6%) and rather average–good for Swiss Olympic (28.6% to 40.9%). During this period, some national sport federations have hired or elected women in top management positions (e.g., rugby in 2013 or gymnastics in 2021) or middle management positions, but such initiatives remain rare. We can isolate a slight positive increase in representation at FOSPO since 2017 and a stronger increase between 2020 and 2021. This observation is comparable to Swiss Olympic for the same period. On the contrary, after a positive evolution in the last two years, the representation of women in SNSF dropped from 2020 to 2021.

Our results for Switzerland contradict evidence from other countries, such as Norway, France or Spain, where the presence of women in decision-making positions or bodies has grown faster in the last years. Most of the period under investigation in our study does not take into account the introduction of a hard measure, such as a quota, which was only communicated in late 2021 for implementation by 2024 and consubstantial to the modification of the Sports Promotion Ordinance. However, this observation suggests that possible soft measures at the micro or meso level within the Swiss sport system may be ineffective in achieving the policy objectives, as the Swiss sport system includes a high degree of cooperation,121 public sector subsidiarity, and autonomy of non-profit sport organisations. On the other hand, we observe a possible effect of “anticipatory obedience” in the period 2020–2021, during which Federal Councillor Amherd activated soft (macro) measures to emphasise the importance of gender representation by calling for more women in sport governing bodies or a better promotion of women in the army with public speeches and interviews.122,123,124 This anticipatory obedience was also observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.125 In parallel, a set of governmental policy documents clearly insist on the topic of diversity in public administration (e.g. Federal Personnel Act). Furthermore, specialised organisations, such as Sporti(f) or Helvetia on Track, were created, and gathering women leaders (including Federal Councillor Viola Amherd) has gained much visibility and legitimacy through important communication campaigns. With awareness-rising power, soft macro-level measures can, therefore, have a catalytic effect to lay the ground for the implementation of stronger measures by sport governing bodies.

In the period of 2020–2021, the interference of the federal government in the governance and management of autonomous non-profit sport governing bodies and the pressure for organisational change have also been backed by two exogenous factors: the particular situation due to the COVID-19 crisis and the “Magglingen protocols” in 2020. Both events have catalysed a larger reform of the Swiss sport system, as they changed power relations and respective expectations among the stakeholders. In the first case, the federal government injected substantial public funds with the intention of limiting the damages caused by the pandemic, which, in turn, stabilised the capabilities of sport organisations. This has reinforced the reporting and accountability processes between public and non-profit sport organisations. In the second case, the “Magglingen protocols” created a climate for reform towards a more ethical and fair sport system, including the amendment of the Sports Promotion Ordinance by 2023. Both events have generated a new sense of urgency in the sport system. The traditional democratic and participatory rather lengthy processes characteristic of the Swiss political system moved into sharper and faster processes tinted with a humanistic approach with regard to sport-related issues. In this vein, the occurrence of these two events created a peculiar sporting climate in the period of 2020–2021, which, in turn, may have influenced the legitimacy and prevalence of the gender narrative in the Swiss sport system.

Compared to other countries, such as Norway, Sweden, or Spain, Switzerland does not have a strong track record in the development and implementation of hard macro-level measures, such as quotas or targets. In Norway, the gender quota system has been implemented for the umbrella federation since 1987.126 In Switzerland, such measures have only emerged in recent years. This mirrors Hovden’s recommendation127 to “fast-track” gender quota implementation to serve as political legitimation to growing stakeholder impatience for advancing gender equity in sport organisations. Building on the experiences of other national contexts, we can expect the overall number of women to increase, especially if the quota is followed by financial sanctioning mechanisms for non-compliance128 and anchored in the Sports Promotion Ordinance. In turn, having more women in decision-making positions reinforces concern and raises social awareness of the issue, as quantitatively more people carry out the narrative. However, building on Hovden,129 the introduction of quotas is not the principal driver when considering the overall distribution of men and women in decision-making positions. It can secure the nomination of women, as requested by related regulations, but other factors can hinder or boost the achievement of the objectives set by the quota, particularly at the meso level. Caprais, Sabatier, and Ruby130 mentioned that the governance structure and representation system of NSF (e.g., number of seats in decision-making bodies, number of management units, type of nomination process, and terms of reference of the position) may influence the decision of a career pathway. This decision is also more broadly related to the number of women candidates for a position, the type of sports disciplines and the width of their participation base (i.e., number of women in the sports discipline). Longitudinal evidence from Spain shows that the higher the position is located in the hierarchy, the more difficult it is for women to access it.131

This study provides new data on gender representation in decision-making positions in the Swiss sport system. It can complement benchmark studies on European countries. It also offers a descriptive account of the measures that promote gender representation. However, it should be pointed out that the literature review is partly based on publicly available policy documents and that the results are based on an interpretation of quantitative descriptive raw data. From there, we do not build evidence on a statistical relationship between the types of measures and their effect, but rather discuss potential causalities. To better understand these mechanisms and also to prove explanatory evidence, a series of qualitative interviews with decision-makers (men and women) should be conducted (e.g., on the ideological resistance to quotas, the type of structural and processual challenges related to implementation within an organisation, the role of leadership or the existence and interplay between macro- and micro-level initiatives that have already been implemented in sport governing bodies). A mixed-methods approach is recommended for further investigation. Qualitative data can be used to explain the effects that emerge from quantitative data. This will allow for grounder research outcomes in the Swiss sport context, comparable to other national case studies and secure the effectiveness of policy measures over the long run. Furthermore, to follow Valiente Fernández,132 who regrets a lack of reflection on the type of organisation that implements a quota (e.g., government, private companies, and non-profits), and Jakubowska,133 Adriaanse, and Schofield134 and Pape, and Schoch,135 who highlight that gender-promotive measures are consubstantial to organisational culture and values, a more representative sampling and sharper segmentation of sport governing bodies should be performed. In our analysis, we included three types of organisations that represent two different sectors – public and non-profit – and that have their own logic. The results for one type of organisation, NSF, are also a clustering of data. In the public sector, we focused on a single organisation (FOSPO). It would be relevant to analyse the impact of a gender quota and its interplay with other measures within each sector.

Conclusion

Improvement of gender representation in sports remains slow, but many initiatives have been undertaken. To date, their effectiveness has been measured using descriptive quantitative benchmark analysis. Although they can be criticised methodologically, they have the advantage of problematising and creating awareness of an issue. Our analysis does not show clear evidence that the number of women who hold decision-making positions in sport organisations is steadily growing in the long run. Building on the literature, we can expect a positive effect after the enforcement of the target in 2024. However, we have also observed that other types of measures can contribute to reaching the policy aim. Therefore, it is an opportunity for researchers to continue to collect and analyse quantitative data among the same sport governing bodies in the long term and sharpen the analysis with a better deconstruction of the decision-making positions within. This, in turn, will provide better evidence to support the implementation of sustainable meso- and micro-level measures for the development of sport organisations and contribute to re-anchoring the principle of the subsidiarity of public intervention and the autonomy of non-profit sport organisations.