3. Prikazi otoka Korčule na odabranim preglednim geografskim i pomorskim kartama Europe i Sredozemlja

3.1. Kartografski prikazi otoka Korčule na pomorskim kartama i izolarima

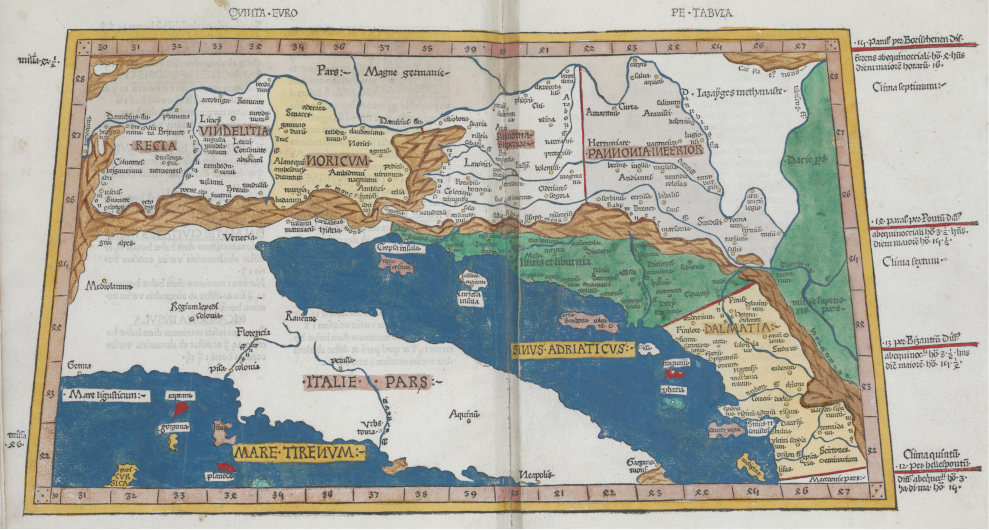

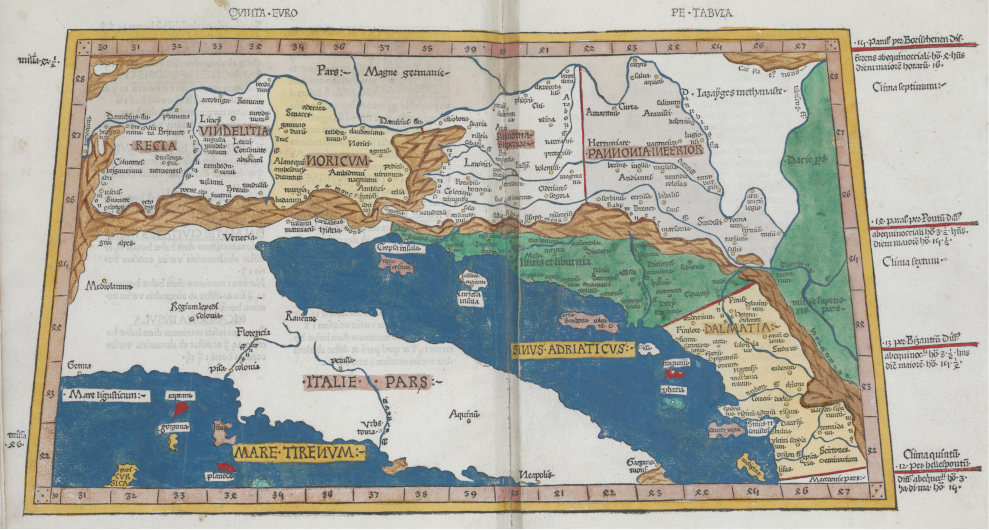

Ako se izuzme Peta karta Europe antičkoga kartografa Klaudija Ptolemeja iz 2. st., koja je za tisak priređena u više različitih inačica od 1477. (Gautier Dalché 2007) pa nije poznat nego se samo može pretpostaviti izgled otoka Korčule na toj antičkoj karti (slika 1), kontinuirano detaljnije kartografsko prikazivanje Jadrana nastupilo je s pomorskim kartama koje su se počele izrađivati najkasnije od kraja 13. st. (Campbell 1987). Na tim je kartama u fokusu bio geografski sadržaj obale kopna i otoka relevantan za planiranje i provedbu navigacijskih zadaća pa su na njima bili imenovani samo oni geografski objekti koji su se uklapali u tu sadržajnu matricu. One su sadržajno bile komplementarne portulanima (plovidbenim priručnicima) pa se za najranije takve karte koristi i naziv portulanske karte. Te karte počele su se izrađivati u razdoblju nadmetanja više jadranskih sila, prije svega Venecije i Ugarsko-hrvatskog kraljevstva, za nadmoć nad sjeveroistočnim dijelom Jadrana. Venecija je, nakon višestrukih prekida od kraja 10. st., od 1409. (na Korčuli od 1420.) utvrdila svoju vlast nad većim dijelom sjeveroistočne obale Jadrana i zadržala je na tom prostoru sve do 1797. (Vrandečić i Bertoša 2007). S ciljem kontrole i upravljanja tim područjem mletačke su vlasti započele s dokumentiranjem i kartiranjem prostornih resursa pa su uz pomorske karte izrađivane i karte koje bi se, po današnjim tipologijama karata s obzirom na njihov sadržaj, mogle svrstati u topografske karte.

Figure 1. Depiction of the island of Korčula on a version of the Fifth Map of Europe by Claudius Ptolemy - excerpt, prepared by J. Reger, Ulm, 1486 (The Renaissance Exploration Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.) / Slika 1. Prikaz otoka Korčule na inačici Pete karte Europe Klaudija Ptolemeja - isječak, priredio J. Reger, Ulm, 1486. (The Renaissance Exploration Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.)

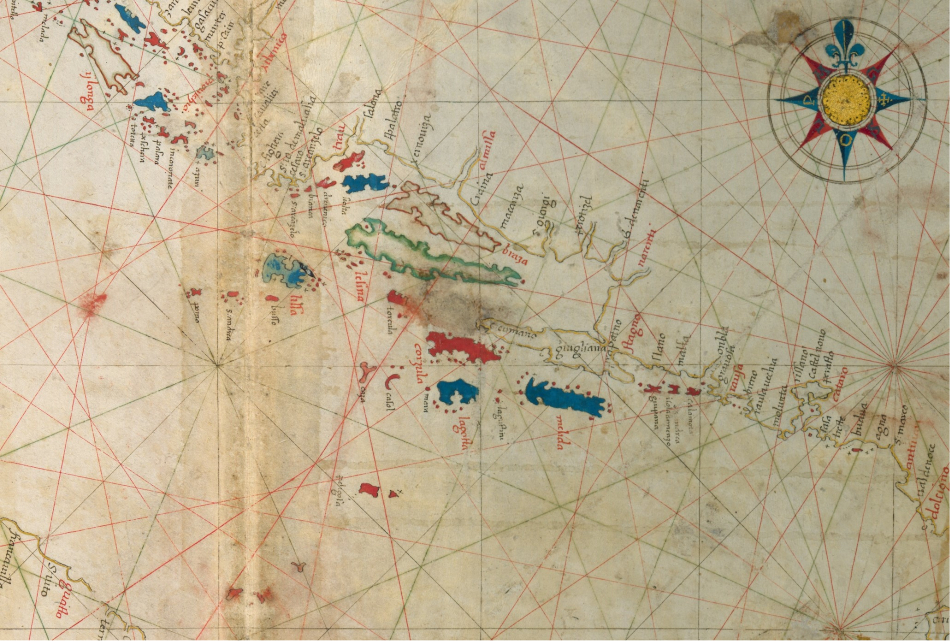

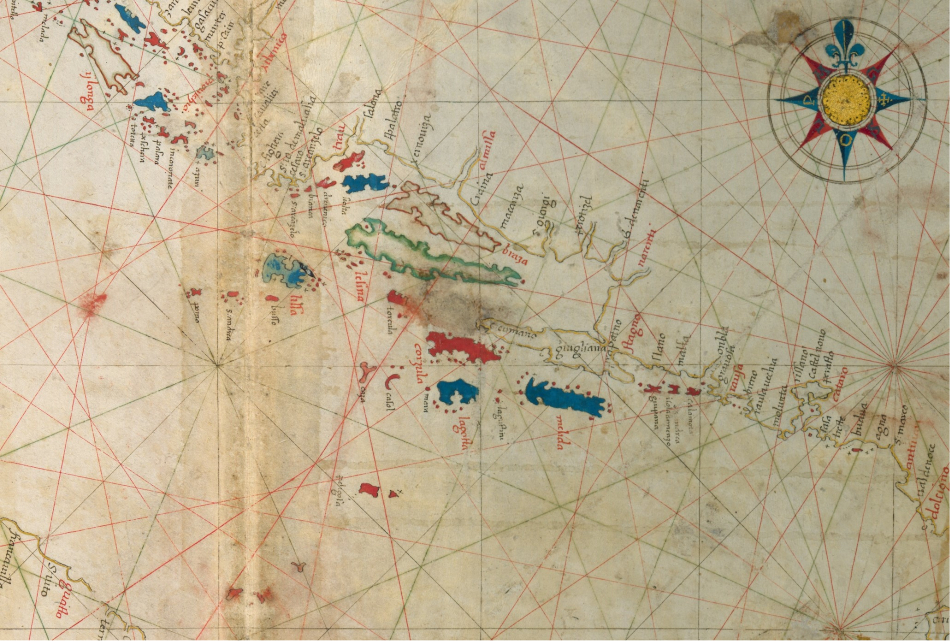

Na pomorskim kartama Jadrana otok Korčula je redovito prikazivan, a najčešće i imenovan. To je logično s obzirom na veličinu i važnost toga južnodalmatinskog otoka. Međutim, prikaz toga otoka ostao je 'zamrznut' stoljećima na preglednim pomorskim i iz njih deriviranim kartama Jadrana.[1] Otok je na karti Jadrana Pietra Vescontea (1318) imenovan kao C(o)rzola (slika 2), a na karti Jadrana Pietra Coppa (1525) kao Curzola (slika 3), što je ime koje pripada mletačkom korpusu jadranske toponimije. Pomorsko-kartografske prikaze jadranske obale, uz venecijanske i druge južnoeuropske autore, izrađivao je i Dubrovčanin Vicko Dimitrije Volčić (Vincentius Demetrius Volcius Raguseus). Na njegovoj pomorskoj karti Jadrana iz 1593. (slika 4) otok Korčula je zabilježen kao Corzula crvenom bojom, kojom je ispisao imena najvažnijih geografskih objekata na moru i kopnu (npr. imena Dubrovnika, Kotora, Stona, otoka Hvara, otoka Visa, Mljeta i Lastova), za razliku od manje važnih geografskih objekata čija je imena ispisao crnom bojom. Volčić, podrijetlom iz grada u relativnoj blizini Korčule, u prikazu obalne crte tog otoka učinio je iskorak u odnosu na starije i strane autore pomorskih karata pa se na njegovom crtežu može jasno prepoznati prostrani zaljev Vela Luke. K tome, ucrtao je mnoge otočiće i grebene u blizini Korčule dajući tako do znanja da je riječ o potencijalno opasnim objektima za plovidbu.

Figure 2. Depiction of the island of Korčula on Vesconti's map of the Adriatic - excerpt, Venice, 1311 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien, Handschriftensammlung, Cod. 594, Tabla 11.) / Slika 2. Prikaz otoka Korčule na Vescontijevoj karti Jadrana - isječak, Venecija, 1311. (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien, Handschriftensammlung, Cod. 594, Tabla 11.)

Figure 3. Depiction of the island of Korčula on Coppo's map of the Adriatic - excerpt, Venezia, 1525 (Lago, Rossit, 1984) / Slika 3. Prikaz otoka Korčule na Coppovoj karti Jadrana - isječak, Venezia, 1525. (Lago, Rossit 1984)

Figure 4. Depiction of the island of Korčula on Volčić's map of the Adriatic - excerpt, Naples, 1593 (National Library of Finland, the A. E. Nordenskiöld Map Collection's maps before year 1800, Sign. N_Kt_103c) / Slika 4. Prikaz otoka Korčule na Volčićevoj karti Jadrana - isječak, Napulj, 1593. (National Library of Finland, the A. E. Nordenskiöld Map Collection's maps before year 1800, Sign. N_Kt_103c)

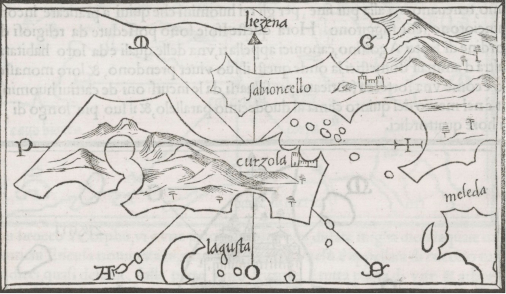

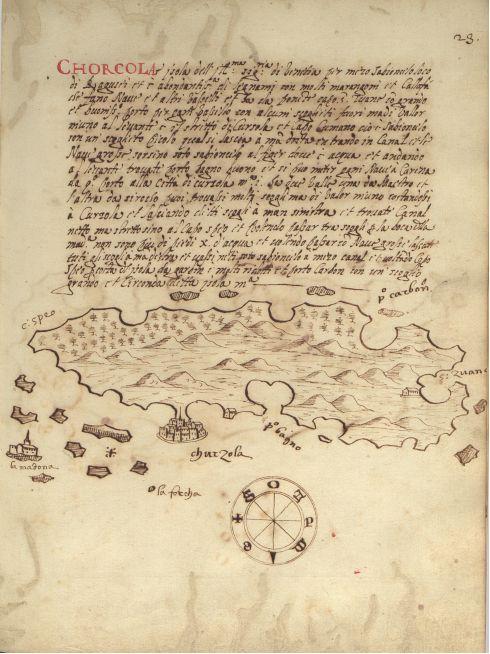

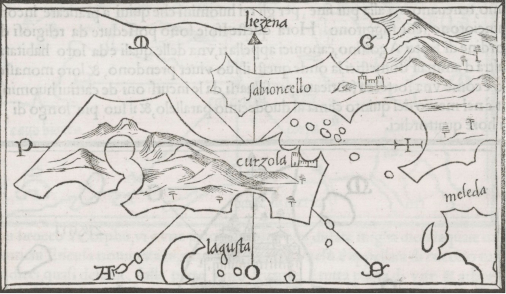

Žanrovski navezani na pomorske karte i portulane bili su izolari. To su zbirke karata priobalnoga područja s pripadajućim tekstovima (ponajprije opisima otoka i luka) na kojima prevladavaju prikazi otoka (Kozličić 1995,Faričić i dr. 2020). Prvi među izolarima s prikazom hrvatskih otoka bio je Isolario nel qual si ragiona di tutte l'Isole del mondo Benedetta Bordonea, koji je tiskan u Veneciji 1528. (Kozličić 1995). U inačici Bordoneova izolara iz 1534. prikazano je više hrvatskih otoka, a među njima i Korčula. Otoci i obala prikazani su generalizirano. Na otoku je prikazano samo jedno naselje - grad Korčula (curzola), dok je među većim uvalama prikazan, ali ne i imenovan Velalučki zaljev (slika 5).

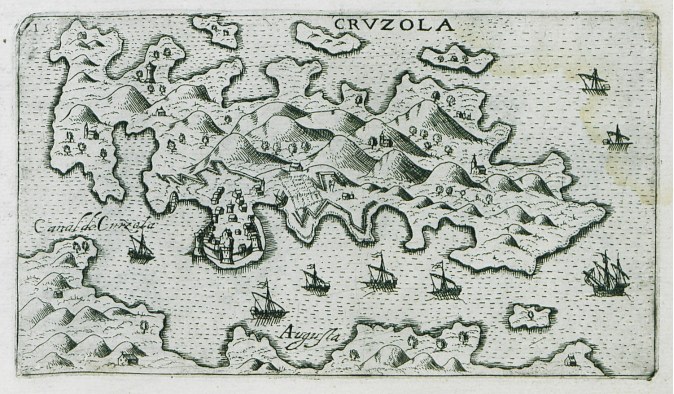

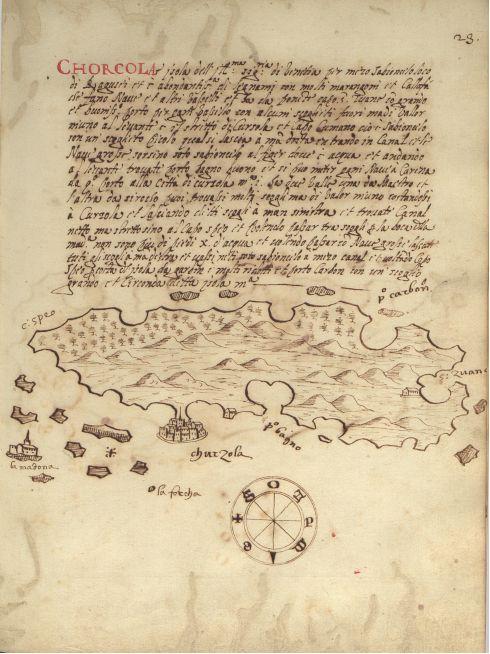

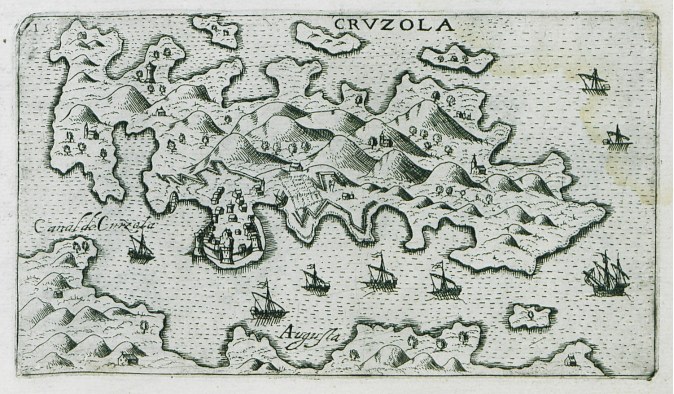

U Camociovom izolaru Isole famose porti, fortezze, e terre maritime sottoposte alla Ser.ma Sig.ria di Venetia, ad altri Principi Christiani, et al Sig.or Turco (1574), otok Korčula je prikazan s utvrđenim gradom Korčulom (CVRZOLA) koji omeđuju dvije uvale s brodogradilištima (squeri) te s kratkim opisom opsade i obrane grada Korčule od turske flote 1571. (slika 6). Na istoj su karti prikazani otoci u Pelješkom kanalu: Bobarda (ime koje se vjerojatno referira na obližnje korčulansko naselje Lumbardu), Lamadona (otočić Badija s franjevačkim samostanom), Fornase (od tal. fornace, pećnica što bi moglo označavati vapnenicu na otoku Majsanu) i Forcha (najvjerojatnije otočić Lučnjak). Prikazani su i otočići na južnoj strani otoka Korčule La lima (Mali i Veli Pržnjak, Trstenik, Gredica i Lukovac) i Carbon (Zvirinovik koji se nalazi ispred luke Karbuni). Na zapadnoj strani otoka nije upisan nijedan toponim. Grčki pomorac i kartogrtaf Antonio Millo je u svom djelu Isulario et Portolano iz 1582. otok Korčulu imenovao kao CHORCOLA, a utvrđeni grad Korčula kao churzola (slika 7). Na Millovoj karti Korčule prikazani su svi otočići kao i na Camociovoj karti Korčule, ali imenovani su samo Lamadona i Forcha te Carbon. Francuski kartograf André Thevet otok Korčulu je prikazao na karti u plovidbenom priručniku Le Grande Insulaire et Pilotage, 1586. (Faričić i dr. 2020). Thevet je otok imenovao nesonimom Isle de Cursola, a grad Korčulu ojkonimom Cursola (slika 8). Prikazao je i sve otočiće koji su prikazani na Camociovoj i Millovoj karti dok je na sjevernoj strani otoka posebno istaknuo one uvale koje su dobre za sidrenje (Bonne sonde). Kartograf Giuseppe Rosaccio u djelu Viaggio da Venetia a Costantinopoli iz 1598. otok Korčulu (CRVZOLA) prikazao je bez obližnjih otočića u Pelješkom kanalu (između otoka Korčule i poluotoka Pelješca). Taj kanal je imenovao hidronimom Canal de Curzola koji se danas odnosi na Korčulanski kanal između otoka Hvara i otoka Korčule (slika 9).

Figure 5. Depiction of the island of Korčula in Benedetto Bordoneo's isolario, Venice, 1534 (Stanford Libraries, Renaissance Exploration Map Collection, Maps and Atlases from the Renaissance Period) / Slika 5. Prikaz otoka Korčula u izolaru Benedetta Bordonea, Venecija, 1534. (Stanford Libraries, Renaissance Exploration Map Collection, Maps and Atlases from the Renaissance Period)

Figure 6. Depiction of the island of Korčula in Giovanni Francesco Camocio's isolario, Venice, 1574 (Historical Library, Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Piraeus, Travelogues - Travelers' Views) / Slika 6. Prikaz otoka Korčula u izolaru Giovannija Francesca Camocia, Venecija, 1574. (Historical Library, Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Piraeus, Travelogues - Travelers' Views)

Figure 7. Depiction of the island of Korčula in Antonio Millo's isolario, Venice, 1582 (Sylvia Ioannou Foundation, Liechtenstein, Books and manuscripts, Sign. B.0254., f.21b) / Slika 7. Prikaz otoka Korčule u izolaru Antonija Milla, Venecija, 1582. (Sylvia Ioannou Foundation, Liechtenstein, Books and manuscripts, Sign. B.0254., f.21b)

Figure 8. Depiction of the island of Korčula in Andre Thevet's isolario, Paris, 1586 (British Library, King George III's Topographical Collection, Sign. K.Top.113.46) / Slika 8. Prikaz otok Korčula u izolaru Andrea Theveta, Pariz, 1586. (British Library, King George III's Topographical Collection, Sign. K.Top.113.46)

Figure 9. Depiction of the island of Korčula in Giuseppe Rosaccio's isolario, Venice, 1598 (Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation, Piraeus, Travelogues - Travelers' Views) / Slika 9. Prikaz otoka Korčule u izolaru Giuseppea Rosaccia, Venecija, 1598. (Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation, Piraeus, Travelogues - Travelers' Views)

Prevladavajuće obilježje prikaza otoka Korčule u izolarima Camocia, Milla, Theveta i Rosaccia ogleda se u deformiranosti prikaza obalne crte i oblika otoka. Prikaz istočne obale otoka Korčule tj. prostora grada (poluotoka) Korčule se redovito prostorno preuveličavao u odnosu na ostale prostorne cjeline otoka. Na taj način se vjerojatno htjela istaknuti važnost upravnog i pomorskog položaja grada Korčule. Prikaz realne izduženost otoka Korčule i zapadno-istočnog pružanja, s gradom Korčulom na istočnoj, a Velalučkim zaljevom na zapadnoj obali je u potpunosti izostao na svim kartografskim prikazima. Ta su izobličenja ponajprije posljedica slabog poznavanja geografskih obilježja prikazanog prostora i izostanka jedinstvenog linearnog mjerila (Faričić i dr. 2020). Izuzetak je Millov kartografski prikaz koji je na zapadnom kraju otoka Korčule ucrtao duboki zaljev s kaštelom i toponimom sv. Ivan (s. Zuane). Takav prikaz zapadnog dijela otoka donekle reflektira stvarno stanje jer su se u Velalučkom zaljevu u 16. st. nalazila četiri kaštela korčulanskih plemića te crkvice sv. Vicenca i sv. Ivana u Gradini (Maričić 1997).

U razmatranju otoka i grada Korčule potrebno je istaknuti još jednu specifičnost. Naime, tijekom srednjega i ranoga novog vijeka grad Korčula je imao veliku važnost. Povoljan geoprometni položaj grada i Pelješkog kanala rezultirao je kartografskim ostvarenjima s naglašenim prikazima istočnog dijela otoka Korčule. Za razliku od istočnog dijela otoka koji je umnogome bio obilježen urbanim i pomorskim funkcijama grada Korčule, zapadni dio otoka bio je agrarni prostor izrazito ruralnih obilježja. Na tom dijelu otoka poljoprivreda je bila glavna gospodarska djelatnost koja se razvijala na relativno velikim agrarnim površinama koje su pripadale Blatu (Campi Blatta). U središnjem dijelu otoka bila su polja koja su pripadala Smokvici (Campus Smoquize) i Čari (Campus Magnus Carre) dok je na istočnom dijelu otoku bio tek manji broj polja i to u Lumbardi (Campus Lombarde) i Žrnovu (Campus Zernove). U okolici grada Korčule nije ih bilo (Dokoza 2009). Takva geomorfološka obilježja utjecala su na razmještaj i razvoj naselja. Pogodnost geografskog položaja Blata zasnivala se na smještaju uz najznačajnije otočne agrarne površine, ali i udaljenošću od mora i okruženošću uzvisinama, a s time i zaštićenošću od napada gusara i pirata. Blato na najstarijim prikazima otoka Korčule nije bilo kartirano, zacijelo ponajprije zbog toga što su oni bili usmjereni na prikaz obalnog prostora. Istodobno, na kartama Korčule objavljenim u izolarima na zapadnoj obali tog otoka nije imenovan ni najveći otočni zaljev, Velalučki zaljev, već uvale ispred otočića La lima i Carbona na južnoj obali otoka. To je posljedica unutarotočne prometne povezanosti odnosno činjenice da Velalučki zaljev - iako sigurno sidrište - nije bio u upotrebi već je jedina izvozna luka otoka bila Korčula. Transport poljoprivrednih proizvoda sa zapadnog dijela otoka do grada Korčule išao je preko luka Prigradice i Prižbe. Naime, grad Korčula je ovisio o uvozu žita iz Sicilije i južne Italije, međutim ta ovisnost je dijelom ublažavana proizvodnjom žitarica, osobito ječma, na blatskim poljima (Dokoza 2003).

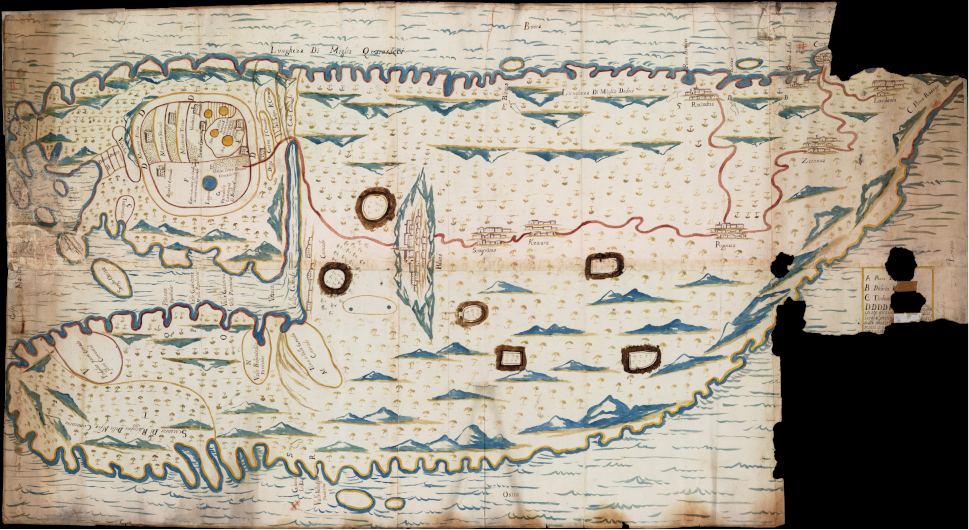

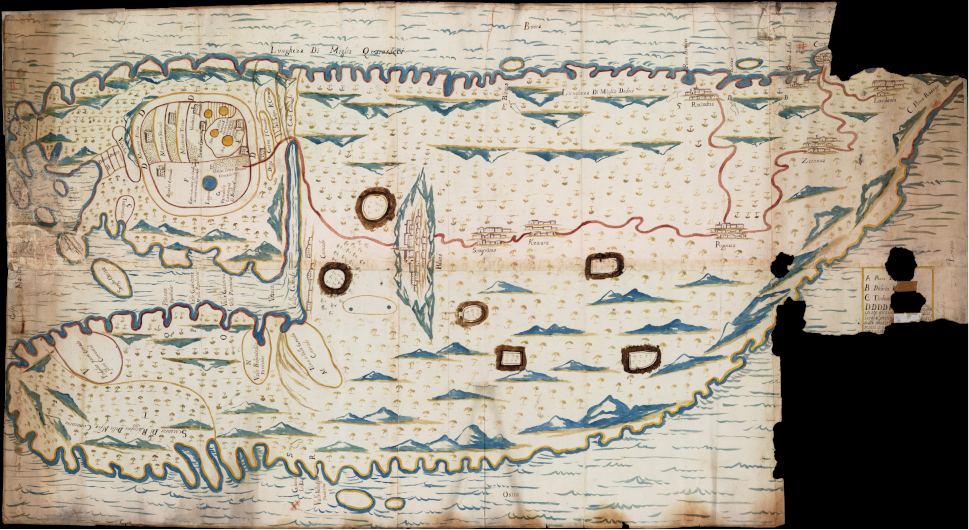

3.2. Kartografski prikaz otoka Korčule nepoznatog autora iz Archivio do Stato di Venezia

Dok su geografski sadržaji zapadnog dijela otoka Korčule na pomorskim kartama uglavnom izostavljeni, u tome pogledu mnogo je bogatija karta otoka Korčule nepoznatog kartografa iz Archivio do Stato di Venezia. U tom se arhivu karta datira u drugu polovicu 16. st., ali niti jedan podatak na karti nas nije naveo da potvrdimo ili odbacimo takva dataciju. K tome, uz kartu nije vezan niti jedan poznati dokument (ili ga mi našim propustom nismo pronašli) pa nisu jasne ni okolnosti njezina nastanka. Nažalost, karta je vrlo oštećena na dijelu u kojem se nalazi kartuša s tekstom. Sačuvani dio teksta nema niti jednu riječ koja bi upućivala na autora, okolnosti i vrijeme nastanka karte. Skloni smo, stoga, dataciju ipak postaviti šire pa pretpostaviti da je karta nastala ili u drugoj polovici 16. ili u prvoj polovici 17. st. Naime, žanrovskih analogija toj rukopisnoj karti Korčule nema u 16 st., dok iz prve polovine 17. st. potječu detaljniji prikazi pojedinih hrvatskih otoka ili dijelova otoka pod mletačkom upravom kao što je, primjerice, Garsoganijeva karta Sutomišćice na otoku Ugljanu iz 1610., najstarija rukopisna karta iz zbirke Mape Grimani Državnoga arhiva u Zadru (Faričić 2022).

Za razliku od karata u izolarima koje su bile tiskane i imale su veći odjek, a zasigurno i širu korisničku publiku, rukopisna karta otoka Korčule bila je čuvana u nekom od ureda mletačke državne administracije i nije bila poznata tadašnjoj široj geografsko-kartografskoj zajednici. Zbog toga je njezina komunikacijska uloga nažalost uokvirena unutar mletačke administracije. Tijekom ranoga novog vijeka isti je slučaj bio i s drugim rukopisnim kartama manjih prostornih cjelina koje, jer su bile namijenjene za uvid u prostorne resurse ili za utvrđivanje zemljišno-imovinskih odnosa za koje je bio zainteresiran manji broj službenika i zemljoposjednika, nisu bile javno dostupne, pa stoga nisu mogle poslužiti kao izvor prostornih podataka prilikom izrade tiskanih karata većih prostornih cjelina.

Na polju karte posebno je istaknut zapadni dio otoka Korčule i njegove poljoprivredne površine (slika 10). Posebno je zanimljiva pozornost koja je usmjerena prema Velalučkom zaljevu (Valle Grande) i mnogim toponimima unutar zaljeva (Vranaz, Tudoroviza, Privala, Cursar, Valle Bobovischia, Valle Gabriiza i Piscena Paricolar ) koji se i danas koriste kao imena uvala. Unutar zaljeva imenovan je i poluotočić Sv. Ivan (S. Giovanni) s crkvom te otočići Ošjak (scoglio Osciak) i Proizd (Proisd scoglio ). U dnu Velalučkog zaljeva tada nije postojalo naselje već samo četiri kaštela korčulanskih plemića (Izmaeli, Gabrijelić, Nikoničić i Kanavelić) te crkvice sv. Vicenza i sv. Ivana u uvali Gradina (Maričić 1997). Svi navedeni objekti su ucrtani na kartografskom prikazu, osim crkvice sv. Vicenca u neposrednoj blizini kaštela.

Figure 10. Depiction of the island of Korčula by an unknown author, second half of the 16th century - first half of the 17th century (Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Miscellanea Mappe, Sign. 36) / Slika 10. Prikaz otoka Korčule nepoznatog autora, druga polovica 16. stoljeća - prva polovica 17. stoljeća (Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Miscellanea Mappe, Sign. 36)

Osim u obalnom prostoru, toponimija je bogata i u agrarnom prostoru Bradata (Bradar Conrado) s istaknutom lokvom dok su ostale agrarne površine označene znakom kvadratića. Razmještaj kvadratića u okolici Blata, Smokvice i Čare odgovara agrarno najznačajnijim površinama na otoku. Iako je zapadni dio otoka bio u fokusu nepoznatog autora, on ne ističe, kako bi se očekivalo, u prvi plan agrarno najznačajnija blatska polja. Naime, na zapadu otoka Korčule agrarnu okosnicu razvoja su činili Blatsko polje - Donje blato, te Potirna, ali poljoprivredna proizvodnja bila je disperzirana na svim poljima ili blagim padinama zapadnog dijela otoka. Uz agrarnu, prednost polja Bradat je bio i geografski položaj. Polje je bilo smješteno u sjevernom dijelu Velalučkog zaljeva i imalo je neposredan izlaz na zaljev ili lučicu Gradinu sv. Ivana koja je bila u potpunosti zaklonjeno sidrište. Uvala Gradina od prapovijesti je bila važna kao točka dodira na plovidbenom putu koji povezuje istočnu i zapadnu obalu Jadrana putem tzv. otočnog mosta Gargano - Tremiti - Palagruža - Sušac - Korčula - Hvar - Neretva. Tu povezanost potvrđuje i antička villa rustica u istočnom dijelu polja Bradat tj. zaobalju Gradine preko koje je komunicirala što dokazuje i rimski pristan na sjeverozapadnom dijelu uvale (Borzić 2009). Gradina sv. Ivana imala je i vojnu važnost u pogledu nadzora ulaska u Velalalučki zaljev, ali i nad Viškim kanalom.

Na temelju povijesnih toponima iz malobrojne arhivske građe moguća je, u usporedbi s prikazom na karti iz Venecije, rekonstrukcija agrarnog krajolika. Među spomenutim lokalitetima ističu se Gradina i Bradat, koji se navode u dokumentima o podjeli kneževe zemlje 1411. godine.[2] Polje Bradat spominje se nekoliko puta i u drugim arhivskim dokumentima, kao i njegovi manji dijelovi Bradat stup i Zabradat. Često imenovanje Bradata, ali i manjih prostornih jedinica u arhivskim izvorima upućuje na agrarnu važnosti tog polja. To potvrđuje i vlasništvo nekoliko korčulanskih plemića nad zemljišnim parcelama u tom polju (Dokoza 2022).

Na kartografskom prikazu uz grad Korčulu i njezin uobičajeni panoramski prikaz imenovana su i sva otočna naselja (Blatta, Smogvirza, Kzzara, Pupnara, Zernova, Racischia, Lombarda i Curzola) koja su prikazana stiliziranim crtežom. Pri tome je posebno zanimljiv prikaz Blata koji jasno odražava percepciju naselja kao demografskog i agrarnog središta otoka u ranom novom vijeku.

Zanimljiv kartografski element na karti su manicule[3] koje upućuju korisnika na pet otočnih uvala. To su uvala Grdača (Grherda) na južnoj strani otoka, te uvale Blaca (Blazza), Vaja ili Samograd (Porto Barbier), Kneža (Knexa) i najvjerojatnije Žrnovska banja (Sirechia Luka) na sjevernoj strani otoka Korčule. Teško je odrediti zašto su te luke dodatno istaknute kartografskim znakom male ruke. Može se pretpostaviti da je namjera nepoznatog autora bila istaknuti ključne luke za unutarotočnu pomorsku komunikaciju, odnosno luke koje su povezivale grad Korčulu s ostatkom otoka.

Kartografski prikaz otoka Korčule izdvaja se među dosadašnjim poznatim i dostupnim kartografskim prikazima otoka. Naime, svi drugi prikazi tog otoka, uglavnom mletačkih, ali i drugih europskih autora, sadržajno su se podudarali. U pravilu su zadržavali isti obalni prikaz s isticanjem grada Korčule i Pelješkog kanala afirmirajući upravno značenje grada, ali i važnost otoka u pomorsko-geografskom sustavu Jadrana i Sredozemlja.

Kako je već istaknuto, mletačka uprava nad većim dijelom sjeveroistočne obale Jadrana zahtijevala je i veći angažman venecijanskih vlasti oko kartiranja jadranskih prostornih resursa. S obzirom na prevladavajuće uopćene prikaze Korčule na kartama Jadrana, najvjerojatnije je i karta nepoznatog autora nastala kao odraz težnji mletačkih vlasti za detaljnijim kartiranjem otočnog prostora koji do tada bio poznat samo u osnovnim crtama.

3.3. Kartografski prikazi otoka Korčule tijekom 17. i 18. stoljeća

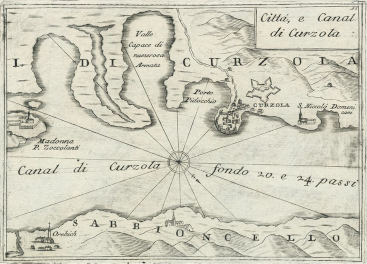

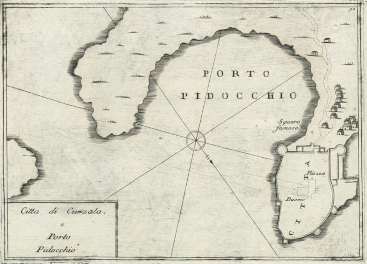

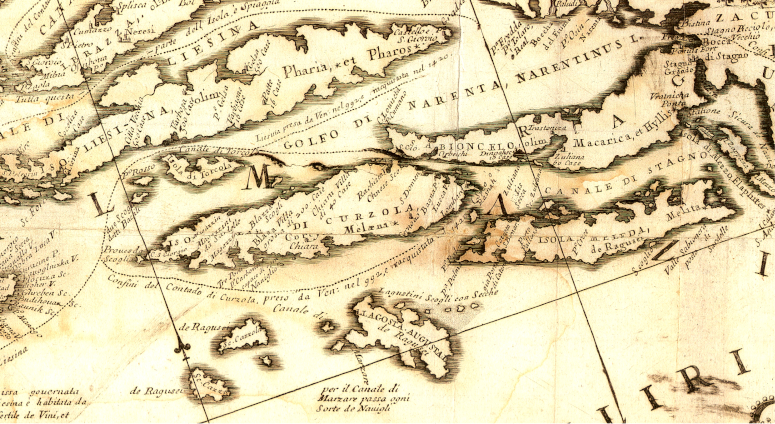

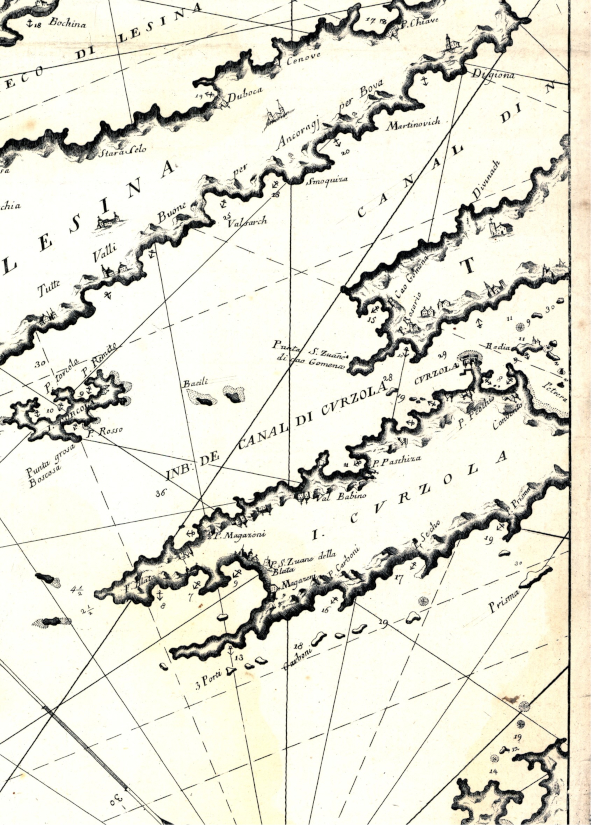

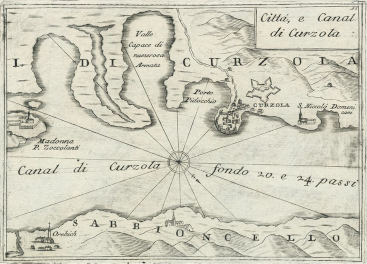

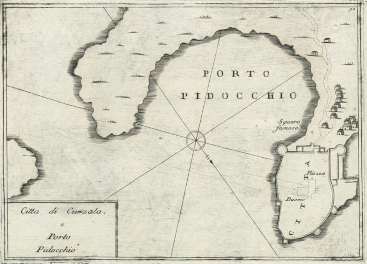

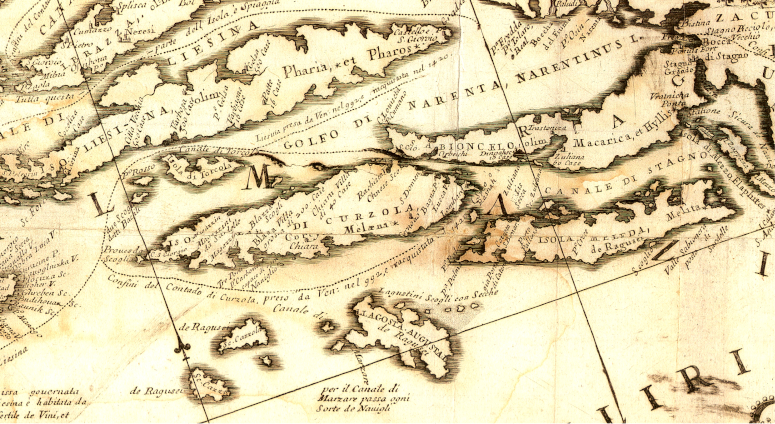

Mletački interes za kartografskim prikazom sjeveroistočne obale Jadrana dodatno je osnažen političkim okolnostima u 17. i početkom 18. st. Veći dio današnje Hrvatske bio je ustrojen kao pogranični prostor imperijalnih sila Habsburške Monarhije, Osmanskog Carstva i Mletačke Republike. U tom razdoblju došlo je do tri rata između Venecije i Osmanskog Carstva - Kandijski rat (1645-1669), Morejski rat (1684-1699) i Drugi morejski rat (1714-1718). Tijekom tih ratova Venecija je izgubila svoje posjede po kojima su ti ratovi nazvani (Kandija - Kreta i Moreja - Peloponez), ali je znatno proširila svoj posjed u zaobalju sjeveroistočne obale Jadrana. U tom kontekstu Venecija je nastojala dobiti što preciznije kartografske prikaze starih i novih stečevina svog prekomorskog posjeda na Jadranu (Mayhew 2008). U kvaliteti prikazivanja današnjega hrvatskog primorskog prostora istaknuo se mletački kartograf Vincenzo Maria Coronelli koji je izradio više desetaka karata s prikazima pojedinih dijelova jadranskoga priobalnog pojasa. Prikaz socio-geografskih sadržaja otoka Korčule Coronelli je dao na karti Dubrovačke Republike koja je objavljena u Veneciji 1688. (Stato di Ragusi Bocca del Fiume Narenta, Isole di Lesina e Curzola nella Dalmatia prosedutte Dalla Serenissima Republica di Venetia)(slika 11). Na južnoj strani otoka prikazana je uvala Karbuni (Carbone) uz napomenu da je pogodna za sve vrste brodova, a dodatno je točkastom crtom i slovom d označena plovidbena ruta između otočića Zvirinovika i Obljaka. Na sjevernoj strani otoka prikazane su i opisane uvale Blaca (Blazza) kao luka pogodna za manje brodove tj. barke, uvala Rašišće (Rachisca) kao luka koja nije pogodna za sidrenje u slučaju da pušu bura (Greco) i sjevernjak (Tramonta) te Žrnovska banja (Bagna) kao luka dobra za sve vrste brodova. Na zapadnom dijelu otoka u trima lukama su označena skladišta usoljenih srdela i vina i to u Velalučkom zaljevu (Magazzini da Sardelle e Vino) te u uvalama Triporte i Prigradica (Magazzini). U prikazivanju istočnog dijela otoka Coronelli nije donio značajnijih novosti. Detaljniji prikaz grada Korčule (slika 12 i13) objavljen je u njegovoj zbirci karata, planova i veduta Mari, Golfi, Isole, Spiaggie, Porti, Citta, Fortezze, ed altri Luoghi Dell' Istria, Quarner, Dalmazia, Albania, Epiro, e Livadia u Veneciji 1694. Na njima je istaknuta luka Pidocchio[4] i podatak o dubini Pelješkog kanala: Canal di Curzola fondo 20 e 24 passi[5], te brodogradilište za koje je upisano da je 'čuveno, cijenjeno' (squero famoso), čime je za razliku od Camocija koji je također prikazao korčulanske škverove, dao dodatnu kvalitativnu oznaku za tu gospodarsku djelatnost.

Figure 11. Coronelli's depiction of the island of Korčula on a map of the Dubrovnik Republic - excerpt, Venice, 1688 (Library of State Archives in Zadar, Zadar, Sign. II. A*) / Slika 11. Coronellijev prikaz otoka Korčule na karti Dubrovačke Republike - isječak, Venecija, 1688. (Državni arhiv u Zadru, Zadar /dalje HR-DAZD/, Knjižnica, Sign. II. A*)

Figure 12. Map of the Korčula and Pešeljac Channel area, Venice, 1694 (Library of State Archives in Zadar, Zadar, Sign. II. A*) / Slika 12. Karta užeg područja Korčule i Pelješkog kanala, Venecija, 1694. (HR-DAZD Knjižnica, Sign. II. A*)

Figure 13. Coronelli's map fo the city of Korčula, Venice, 1694 (Library of State Archives in Zadar, Zadar, Sign. II. A*) / Slika 13. Coronellijev plan grada Korčule, Venecija, 1694. (HR-DAZD, Knjižnica, Sign. II. A*)

Coronelli je poopćene prikaze grada Korčule dao i na drugim kartama. Na karti Dalmacije iz 1694. godine označene su granice dalmatinskih okruga (contadi) na kopnu i na moru (slika 14), te godine mletačkog zauzeća pojedinih obalnih i otočnih komuna. Unutar Korčulanskog okruga koji je uspostavila mletačka vlast 1420. godine (Dokoza 2009) uz otok Korčulu i pripadajuće otočiće Coronelli je obuhvatio i otok Šćedro (Isola di Torcola). Naveo je da su Mlečani zauzeli Korčulu 992., a zatim ponovno 1420. Uz uvale na zapadnom dijelu otoka označio je skladišta (Magazzin, Magazzini da Sardelle i Magazzini) što upućuje na gospodarsko značenje tog dijela otoka. Za naselje Blato uz ojkonim je istaknuta i veličina naselja (Blatta Villa grossa di 200 casa). Coronelli je, kao i autori karata u izolarima, istaknuo važnost otočnih luka i to na južnoj obali otoka (Carboni, Tre Porte) uz bilješku da su te luke dobre za sve vrste brodova.

Tijekom 18. stoljeća Coronellijeva geografska građa je kod mnogih europskih kartografa prihvaćena kao predložak za različite reprodukcije prikaza Jadrana. Coronellijev utjecaj zadržan je i kod prikaza Korčule, što se, uz ostalo, vidi i na kartama francuskog hidrografa i kartografa Jacquesa Nicolasa Bellina. Zanimljiv je njegov odabir korčulanskih toponima na karti Jadrana iz 1771. godine (slika 15). Uz ime otoka istaknuo je pripadnost otoka Veneciji (I DE CURZOLA aux Venitiens). Iako je riječ o pomorskoj karti, Bellin je korisnicima dao i relevantne političko-geografske informacije približavajući im političke odnose na Jadranu. U ovom slučaju Bellinova je namjera bila razgraničiti teritorij između dviju Republika pa je tako otok Korčula označen kao mletački, a otok Mljet kao dubrovački posjed. Bellin je posebno imenovao Blato (Blatta) koje je prikazano s crkvom te Lumbardu (Lombara) i Čaru (Chiara). Od hidrografskih elemenata označena su sidrišta na zapadnoj strani otoka - Velalučki zaljev i luka Tri porte (Les trois Ports bons pour tous Vaiβeaux) na jugozapadnoj obali, koja je, Coronellijevim tragom, opisana kao dobra luka za sve brodove. Na istočnoj obali je istaknuto sidrište u Pelješkom kanalu te na sjevernoj obali u uvali Kneža ili Žrnovska banja. Zanimljivo je, međutim, da Bellin na karti Jadrana nije prikazao grad Korčulu. Štoviše, to nije učinio ni na karti dijela dalmatinske obale od Rogoznice do Stona (Coste de Dalmatie entre Ragoniza et Stagno) na kojoj je dao detaljniji prikaz otoka Korčule (slika 16) poput onoga koji se nalazi na Coronellijevoj karti Dalmacije. To je primjer kako je kartografska generalizacija nedovoljno upućenoga kartografa „pomela“ važan geografski sadržaj.

Figure 14. Coronelli's depiction of the island of Korčula on a map of Dalmatia - excerpt, Venice, 1694 (Library of State Archives in Zadar, Zadar, Sign. II. A*) / Slika 14. Coronellijev prikaz otoka Korčule na karti Dalmacije - isječak, Venecija, 1694. (HR-DAZD, Knjižnica, sign. II. A*)

Figure 15. Depiction of the island of Korčula on a map of the Adriatic -by Jacques Nicolas Bellin - excerpt, Paris, 1771, (National and University Library, Atlas and Map Collection, NSK-SJZXVIII-145_001) / Slika 15. Prikaz otoka Korčule na karti Jadrana Jacquesa Nicolasa Bellina - isječak, Paris, 1771. (Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica, Zbirka atlasa i zemljovida, NSK-SJZXVIII-145_001)

Figure 16. The island of Korčula on Bellin's map of the central part of the Dalmatian coast - excerpt, Paris, 1771 (University of Split Library, Split, Map collection, R-684) / Slika 16. Otok Korčula na Bellinovoj karti srednjeg dijela dalmatinske obale - isječak, Paris, 1771. (SKST, Kartografska zbirka, R-684)

Coronellijev geografski sadržaj nije bio jedini predložak koji je poslužio za mnoge kasnije nekritičke, a kadšto i nekvalitetne reprodukcije. Naime, odvojeno od koronelijanskog niza karata razvijao se jedan drugi osamnaestostoljetni dijakronijski reprodukcijski niz. Mletačke su vlasti poslije ratova s kraja 17. i početkom 18. st. organizirale izradu korografskih, odnosno topografskih karta Dalmacije. Izradi tih karata nisu prethodile sustavne geodetske izmjere premda su mjernički postupci bili provedeni s ciljem određivanja, a zatim i iscrtavanja novih mletačko-habsburško-osmanskih granica. Na tim korografskim kartama uspostavljen je geografsko-kartografski obrazac koji se, uz onaj Coronellijev, zadržao se sve do kraja 18., odnosno do početka 19. st. kada već anakroni korpus geografskih podataka postupno zamjenjuje sadržaj topografskih i pomorskih karata koje su nastale kao rezultat topografske i hidrografske izmjere današnjega primorskog dijela Hrvatske (Faričić 2011,2017;Kozličić i Faričić 2016). U pogledu prikaza otoka Korčule na korografskoj karti Dalmacije, koju je u Zadru oko 1718. izradio nepoznati autor (možda Francesco Melchiori koji je tada bio istaknuti kartograf u službi mletačke uprave u Dalmaciji), razlikuje se od Coronellijevih karata po mnogo boljem prikazu obalne crte te imenovanjem pojedinih manjih uvala i otočića na južnoj (Trastenich, Bercich, Trepozzi, Porto Simon, Chandria vala, Rocotniza, Perina vala) i sjevernoj (Rachisca vala, Rasohattiza) obali otoka. Od krajnjih geografskih točki otoka imenovani su na zapadnom dijelu otočić Čančir (Cao Cancara) i rt Kursar (Cao S. Zorzi), a na istoku rt Ražanj (Cao Rasagn) (slika 17). Međutim, neki drugi elementi preuzeti su od Coronellija poput antičkog imena otoka i prikaza administrativnih granica Korčule s godinama mletačkog zauzeća tog otoka (ali tim granicama nije obuhvaćeno Šćedro).

Napredak u prikazu Korčule zabilježen je kod Giuseppea A. Grandisa, koji je koristeći geografski sadržaj s topografske karte iz 1718., ipak obavio odgovarajuće izmjene i dopune na rukopisnoj topografskoj karti Dissegno o' carta topografica della Dalmazia koju je izradio u Zadru 1781. Na toj karti prikaz otoka Korčule je realniji zbog preciznijeg prikaza obalne crte, te prikaza reljefa crtkanjem pri čemu je Grandis gušćim crticama prikazao veće nagiba padina, a rjeđim crticama padine s manjih nagibom. Od otočnih naselja prikazana su (imenovana i označena kartografskim znakom crvene boje) uglavnom obalna naselja odnosno uvale koje su bitne za pomorsku komunikaciju. Žarišta naseljenosti u unutrašnjosti otoka Blato i Smokvica, pa i Lumbarda koja je na obali, nisu prikazana na toj Grandisovoj karti kao ni na karti Dalmacije iz 1718. Iako je Grandis svoj kartografski prikaz u usporedbi s kartom iz 1718. dopunio toponimima Tankaraca (Tremuli), Prapatna (Prapadna) i Bristva (Brista) na sjevernoj obali otoka, a na južnoj uvalom Brna (Porto Berno) (slika 18), ostao je unutar metodološkog obrasca u kojemu je zanemarena unutrašnjost otoka.

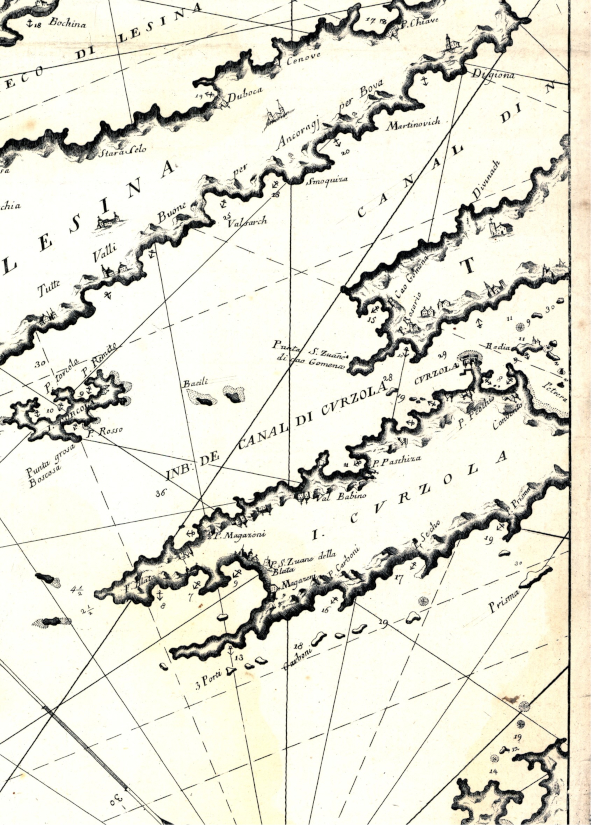

Posljednji ranonovovjekovni kartografski prikaz otoka Korčule je onaj Vincenza di Lucija koji je oko 1790. izradio kartu Jadrana u više listova, među kojima je i list s prikazom otoka i akvatorija kojima pripada i Korčula. Kartografski prikaz Vincenza de Lucija u pogledu prikaza Korčule ipak ne donosi nikakvu novost (slika 19). Na tom prikazu otoka Korčule (I. CVRZOLA) može se primijetiti isticanje toponima na zapadnoj obali otoka. Uz već ustaljene na geografskim kartama (3 Porti, Carboni, Magazeni, P. Magazeni), na toj su pomorskoj karti upisani i toponimi P. Blata i P. S. Zuane della Blatta. Toponim P. Blata odnosi se na krajnji zapadni dio Velalučkog zaljeva tj. prostor Privale. Drugi toponim P. S. Zuane della Blatta upisan je u dnu Velalučkog zaljeva i teško je odrediti na koji dio obale se odnosi. Naime, u zapadnom dijelu otoka nalaze se dvije crkve posvećene sv. Ivanu. Jedna je crkvica posvećena sv. Ivanu Krstitelju u uvali Gradina, a druga je posvećena sv. Ivanu Evanđelistu i nalazi se u naselju Blatu. Imenovanje krajnjeg zapadnog dijela otoka tj. punte Privala s P. Blata upućuje na upravno-teritorijalnu aktualnost, odnosno postupnu litoralizaciju naselja Blata u kojem Velalučki zaljev postaje funkcionalni dio Blata što je u konačnici dovelo do oblikovanja novog naselja Vela Luke.

Figure 17. Depiction of the island of Korčula on a map of Dalmatia by an unknown author - excerpt, Zadar, around 1718 (HR-DAZD-383, State Archives in Zadar, Map collection, Sign. 1.3.1). / Slika 17. Prikaz otoka Korčule na karti Dalmacije nepoznatog autora - isječak, Zadar, oko 1718. (HR-DAZD-383, Kartografska zbirka, Sign. 1.3.1).

Figure 18. Depiction of the island of Korčula on Giuseppe Antonio Grandis's map - excerpt, Zadar, 1781 (HR-DAZD-383, State Archives in Zadar, Map collection, Sign 1.3.3) / Slika 18. Prikaz otoka Korčule na karti Giuseppea Antonija Grandisa - isječak, Zadar, 1781. (HR-DAZD-383, Kartografska zbirka, Sign 1.3.3)

Figure 19. The island of Korčula on a cartographic depiction of the Adriatic by Vincenzo de Lucio - excerpt, Venice, around 1790 (Croatian State Archives, Map collection, E.IV.13.) / Slika 19. Otok Korčula na kartografskom prikazu Jadrana Vincenza de Lucija - isječak, Venecija, oko 1790. (Hrvatski državni arhiv, Kartografska zbirka, E.IV.13.)