1 Introduction

In the Pontifical Croatian College of St Jerome, in Rome, a manuscript geographic map of the Croatian countries is kept, drawn in 1663 by the architect and geographer, Pietro Andrea Buffalini, of Rome. The map dimensions are 155 cm x 100 cm (the outer dimensions of the frame being 190 cm x 125 cm). It contains a display not of a graticule, but of a linear scale bar and a simplified display of the directions of north (marked by a stylized lily sign, commonly known as fleur-de-lis) and east (marked by the sign of a cross) on a blue circle. Although the map has no title, its content and purpose are described in a cartouche: Congregatio Nationis Illyricae sicuti instituta fuit ab Illyricis ex Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosna et Slauonia in Urbem confluentibus; ita eorundem Regnorum Nationales tantum, vel Oriundi, Slavonica tamen lingua loquentes, iurium ipsarum participes esse debent: ut constat ex Decisione Sacrae Rotae diei X Decembris MDCLV coram R.P.D. Priolo: Ideo ad evitandas aequivocationes vel fraudes haec quatuor Regna, fines que eorum delineati fuerunt ut possint distingui quae loca includi, quaeue excludi debeant.[1] It is, therefore, a cartographic representation of four provinces – Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia and Bosnia – which coincide with the geographic name of Illyricum, and from which those who can make use of the rights of the Congregation of the Illyrian (Croatian) nation have the right to come into the pontifical college of St Jerome. It is the first known modern map showing all the large spatial units which were settled at that time by a Croatian population, those who use the Croatian language (Slavonica lingua) (Mlinarić et al. 2012). At the time of the creation of the 1663 map of Illyricum, the area shown was politically divided among three states: the Habsburg Monarchy, the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice, and only the area of the Republic of Dubrovnik functionally practised a high degree of political independence. The map, however, does not reflect particular imperial interests and the narratives associated with them, but the awareness of belonging to the same ethnic or linguistic body, based on the ancient tradition framed by the Roman-era name of Illyricum. From a formal perspective, it is an anachronism, but also a functionally skilful choice of a name that made it possible to spatially encompass varying regional entities. This area is demarcated in relation to the neighbouring European regions by a border whose edge has the text Confini delle quatro prouincie Illyriche. Within this border, not all the areas that were then settled by Croats are shown. Specifically, Istria, Međimurje and the Croatian part of Baranja remain outside the borders. Ivan Črnčić, who was the first to briefly describe the map, offered a reason for excluding Međimurje: “Surely they were afraid of the town of Strigov, where they claim that St Jerome was born” (Črnčić 1886: 69–70). In fact, even at the time of the creation of the map, there was a lively debate about the location of ancient Stridon, which lay, according to Jerome himself, on the border between Dalmatia and Pannonia, and it must have been difficult for advocates of Marulić's thesis that Jerome's Stridon should be the Sidron on Ptolemy's Fifth Map of Europe to 'drag' Međimurje to that border (Bulić 1920,Suić 1986,Margetić 2002).

The 1663 map of Illyricum (Figure 1) is one of the oldest maps of the entire territory of today's Croatia, by which it is possible to precisely determine its utilitarian purpose and detect its users: determining the right to use the services of hospices, or institutes for Catholic Croats in Rome in accordance with the decree of the high judicial authorities of the Papal States to those who lie within the boundaries of the four provinces of Illyricum: Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia and Bosnia.

Figure 1. 1663 Map of Illyricum in the Pontifical Croatian College of St Jerome in Rome / Slika 1. Karta Ilirika iz 1663. u Papinskom hrvatskom zavodu Sv. Jeronima u Rimu

Brief but substantive cartographic analysis of the 1663 map of Illyricum has already been carried out in the scientific literature (Črnčić 1886,Škrivanić 1968,Marković 1993), and the ecclesiastico-legal and historico-geographic context of its genesis has also been analysed (Mlinarić et al. 2012). As a supplement to previous research on the 1663 map of Illyricum, the depiction of the coast on that map is cartometrically compared with that on selected geographic maps and nautical charts from the late 16th century and the first half of the 17th. On the basis of this analysis, we try to determine whether the selected maps served as templates for creating the 1663 map of Illyricum, and whether a qualitative step forward was taken with that map in the rendering of the northeast coast of the Adriatic. In addition, on the basis of research into the available written data sources, we try to contribute to the discussion on the (co)author's contributions to the shaping of the geographic content of the manuscript map of Illyricum.

2 Authorship of the 1663 Map of Illyricum

Stjepan Gradić's contribution to the making of the map

At the time of creation of the 1663 manuscript map of Illyricum, the head of the Fraternity of St Jerome in Rome was Stjepan Gradić (Stefano Gradi, Stephanus Gradius), from Dubrovnik (Krasić 1987: 92). In view of this, some scholars have logically believed that it was actually Gradić who gave Buffalini the necessary geographic data, and that Gradić was not only the legal representative of the client but also the creator of the map that was drawn, technically, by Buffalini. Moreover, Gradić's collaboration with Buffalini was very fruitful in other areas, too. Perhaps the most important achievement of this collaboration is Buffalini's engagement in the design of the new Dubrovnik cathedral, which, according to the design of that Roman architect, was built on the site of the cathedral destroyed in the earthquake that struck Dubrovnik in 1667 (Marković 2012: 83–92). In addition, the edifice of the College of St Jerome in Rome was extended in accordance with Buffalini's project (Gudelj 2014: 375).

In previous research, scientists started from the data that was first presented by Ivan Črnčić, writing about the problem of using the names Slovene and Illyrian in the guesthouse of St Jerome in Rome (Črnčić 1886: 69). The immediate motive for making the map of Illyricum was a dispute over who could be a member of the College of St Jerome in Rome. In 1655, the Sacra Rota Romana ruled that Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia and Slavonia should be considered as Illyricum (Črnčić 1886: 64–66). The Fraternity of St Jerome in Rome ordered the creation of a map of that area on 6 October 1659, and the manuscript map was drawn up by the Roman architect Pietro Andrea Buffalini on 2 September 1663, for which he was paid 36 scudi. Črnčić added that during the creation of the map, the “painter” Buffalini was “directed” by the head of the Fraternity, Abbot Stjepan Gradić, of Dubrovnik, who was the curator of the Vatican Library and a member of the Academy of the Swedish Queen Kristina (Črnčić 1886: 69).

Gradić, in view of his position in the Fraternity of St Jerome, was unquestionably crucial in the choice of person who would draw the map. However, the question arises as to why Buffalini was chosen. Pietro Andrea Buffalini belonged to the academy of Italian artists in Rome under the title of St Luke (Accademia de i Pittori e Scultori di Roma), whose establishment was approved by papal breve in 1577. In the 1696 catalogue he is listed as Pietro Andrea Buffalini Architetto, and the date of his admittance to the academy, 16 June 1673, is noted next to his name (Ghezzi 1696: 51,Gudelj 2016: 193). Buffalini is also mentioned in the scientific literature as a professor of geography at Rome's University of La Sapienza (Bedini 2021, 281), which is also confirmed by a scientific treatise of the 17th century on the observation of celestial bodies, in which he signed himself “Io Pietro Andrea Buffalini Proffesore di Geografia mano propria” (Buffalini 1666: 38).

In Črnčić's wake, Gradić's contribution to the creation of the map was also highlighted by Gavro Škrivanić, stating that the map was created “in accordance with the ideas and instructions of Stiepo Gradić” (Škrivanić 1968: 273), while in another place he calls it “Gradić's map of Illyria-Dalmatia” (Škrivanić 1968: 276), which was “a first-class source for the historical and historico-geographic studies of that time” (Škrivanić 1968: 276). In the same way, the map has been attributed to Gradić by Ćosić and N. Glamuzina, repeating Črnčić's and Gavranović's statements that Buffalini made the map in accordance with Gradić's (Gradi's) instructions, calling that map “Gradi's map” (Ćosić and Glamuzina 2018: 207). Marković believes that it is not correct to refer to the map of Illyricum at the Croatian College of St Jerome in Rome, as Gradić's map, like Škrivanić did, “but it is a synthesis of the joint work of the members of the College with the cartographer Buffalini” (Marković 1993: 175–182, note 12). This was repeated by Slukan Altić, adding that Gradić and his colleagues “in creating the map, did not redraw existing maps, but each member of the College, with respect to their origins, participated in the mapping of that part of Illyricum (Slukan Altić 2003: 130). In support of this, one can highlight the fact that Buffalini, during the making of the map, resided at house no. 17, owned by the Fraternity of St Jerome (Gudelj 2016: 191). Marković states that Ivan Lučić (Giovanni Lucio, Joannes Lucius) used that map (drawn by Buffalini) as a template for the map that was published in the third edition of the book De regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae ('On the Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia') in 1668 (Marković 1993: 182), while Slukan Altić has determined that it was a matter of “Gradić's map, taken over and modified” (Slukan Altić 2003: 132). Judging by the congruence of the geographical content, Lučić's 1668 map Illyricum hodiernum is unquestionably very similar to the 1663 manuscript map of the same area. Our cartometric analysis confirms that it is an almost facsimile depiction of the coastline of the northeast Adriatic coast, which differs from all older and contemporary representations of that coast on maps and charts.

Ivan Lučić of Trogir's contribution to the making of the map

Recent archival research by Gudelj resulted in her claim that “the map was made with the evident help of Gradić and the Trogir historian, Ivan Lučić” (Gudelj 2016: 191). In fact, at the time of the creation of the 1663 map of Illyricum, Ivan Lučić of Trogir, who succeeded Gradić as the leading man in the Fraternity of St Jerome also stayed in the College of St Jerome in Rome (Škrivanić 1968: 273). Dealing primarily with the map of Illyricum printed in 1668 and published in the book 'On the Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia', but also with the 1663 manuscript map of Illyricum,D. Mlinarić et al. (2012) state, relying on the correspondence of the geographical content, that it is Lučić's cartographic achievement. Lučić's authorship of the map, or at least his crucial co-authorial contribution to the shaping of its geographical content, is supported by his words written in the work Memorie istoriche di Tragurio ora detto Traù ('Historical testimonies about Trogir'), published in 1673: “Whoever takes a closer look at various positions will see that, on maps printed thus far, there are many errors, not only in connection with the territory of Trogir, but also with the entire Province. In order to correct this, I have made a new map of today's Illyricum, which consists of four provinces – Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Slavonia – and, with various sketches and notes, I have corrected, to the best of my ability, the errors printed hitherto, encouraging whoever it pleases to look there at correctly drawn positions and to add those corrections that seem to him to be more accurate than what I have printed” (Lučić 1673, translated 1979: 706). Among the Croatian historians of cartography, Kozličić was the first to bring attention to this, pointing out that Lučić's maps have no real analogies in the history of mapping the eastern Adriatic (Kozličić 1995: 218, 220).

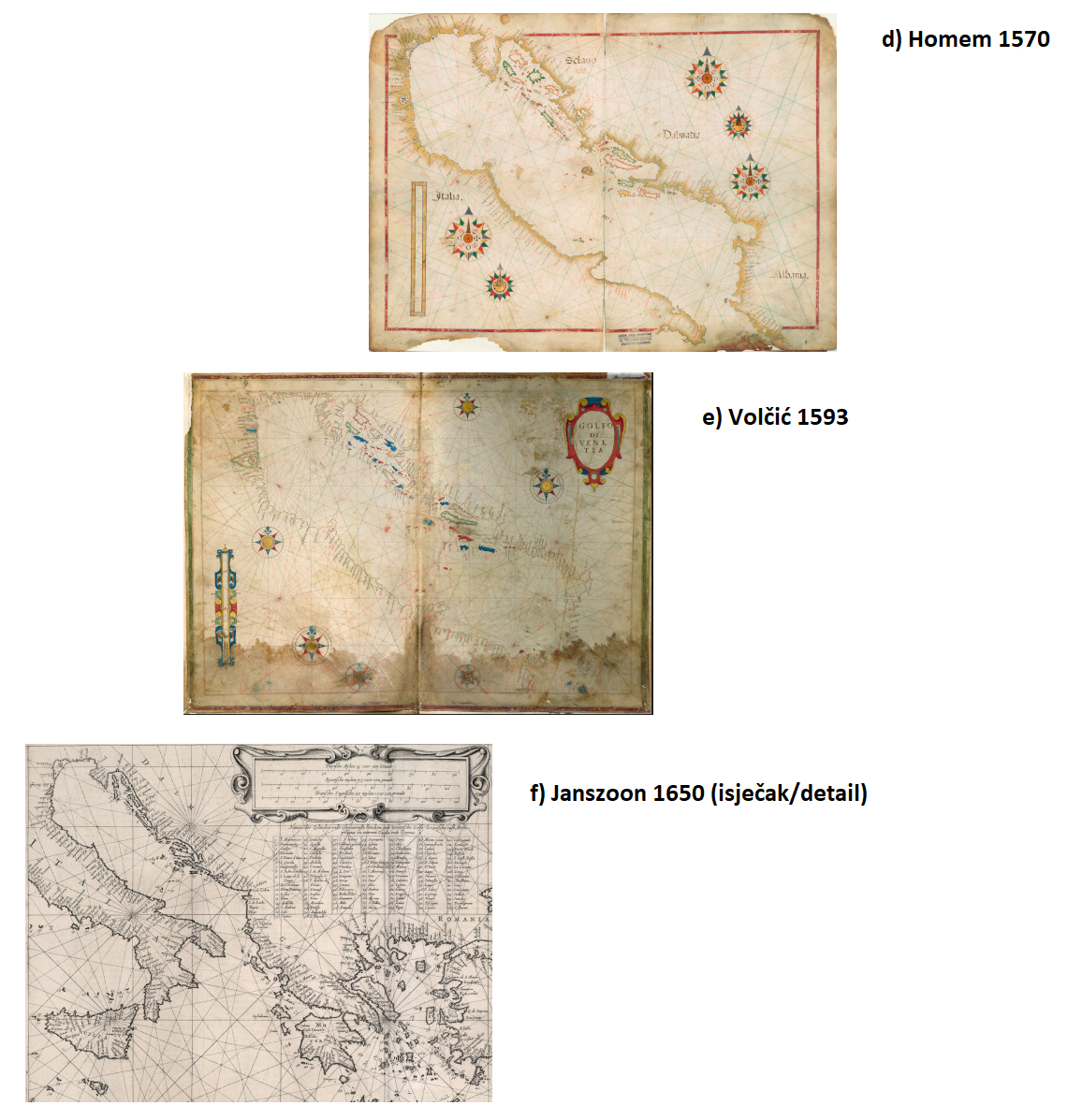

Lučić was aware of the fact that on that map of Illyricum he had given a general depiction without sufficient detail, so in 1676, in a letter addressed to Danijel Difnik of Šibenik, he gave instructions that his brother (Franjo), who was preparing a comprehensive Historia della guerra di Dalmatia tra Venetiani e Turchi ('History of the Candian War in Dalmatia between the Venetians and the Turks'), be forwarded a proposal to supplement his work with a map of Dalmatia, more detailed than his, at least for the areas of Zadar, Šibenik, Trogir, Split and Omiš (Kečkemet 1986: 7–52). In the first edition of his work 'On the Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia', Lučić published five comprehensive and very generalized maps of the coastal part of today's Croatia. Not until the third edition of that book, published in 1668, was the map of 'Today's Illyricum' subsequently included, having been prepared for printing by the Dutch publisher and cartographer Joan Blaeu. Blaeu then published the same map in 1669 in the Atlas Maior / Geographia Blaviana (Figure 2). Blaeu's contribution was similar to that of Buffalini: Lučić (and other co-authors) did not deal with the technical aspect of mapmaking, but he was crucial in defining its geographical content.

Figure 2. 1669 Map of 'Today's Illyricum' published in Blaeu's Atlas Maior / Slika 2. Karta „Današnjeg Ilirika“ iz 1669. objavljena u Blaeuovom Atlas Maior

The publication of the printed map of 'Today's Illyricum' enabled its dissemination throughout Europe. Although its communicative potential was great, it was soon replaced by maps depicting the same area, created by Giacomo Cantelli and Vincenzo Maria Coronelli. Coronelli's maps became templates that, with minor modifications, were prepared for printing by numerous European cartographers during the 18th century, so they became a model for shaping geographical perception, and for cartographic representation of an area that is today an integral part of the Republic of Croatia, in the era that preceded systematic geodetic surveying. On the other hand, the 1663 map of Illyricum became one of the longest-lasting permanently-used manuscript maps; its original, framed and covered with glass like a painting, hangs to this day on the wall in a special room of the Pontifical Croatian College of St Jerome in Rome.

3 Geometric Features of the Coastal Part of the Map

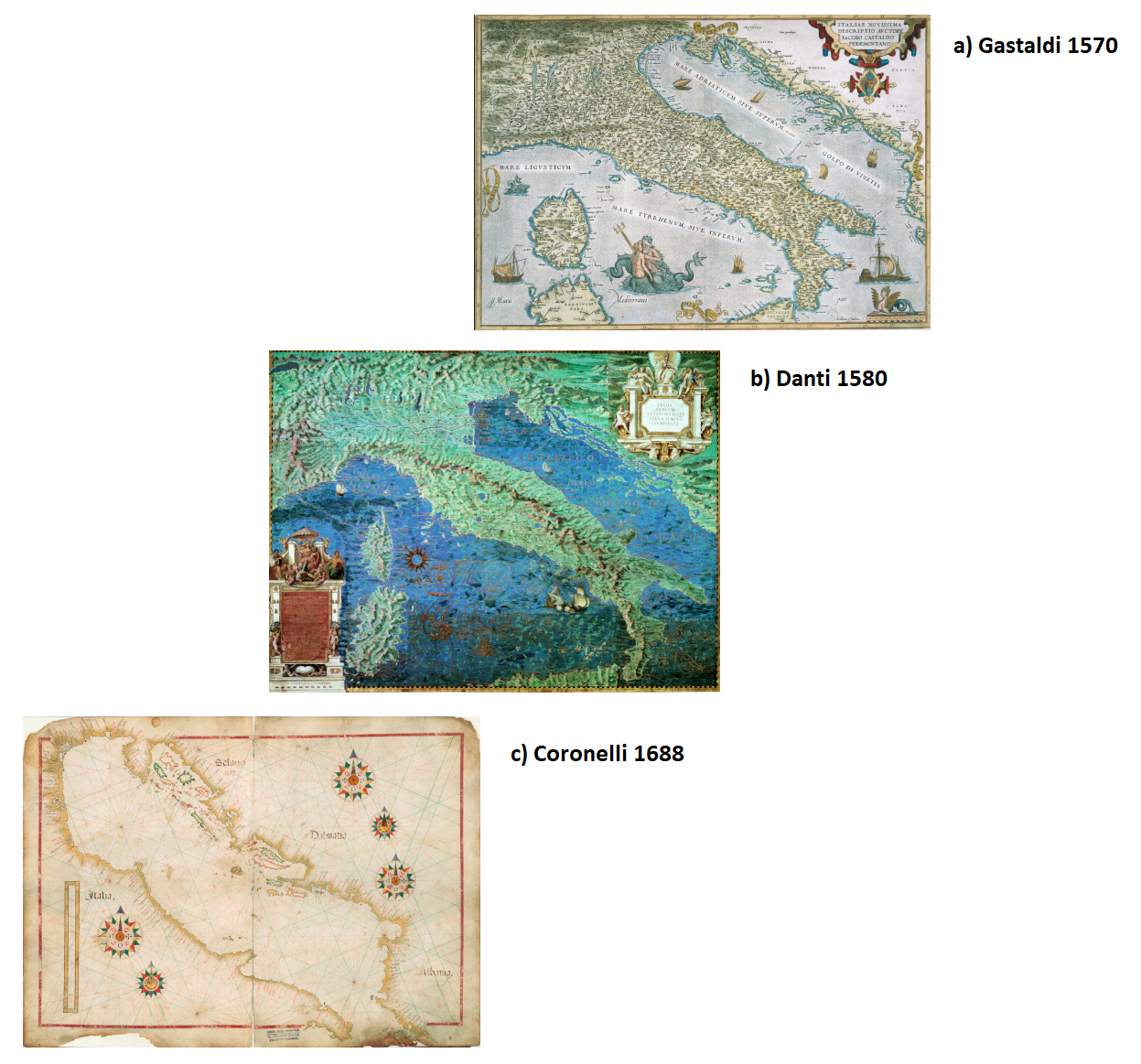

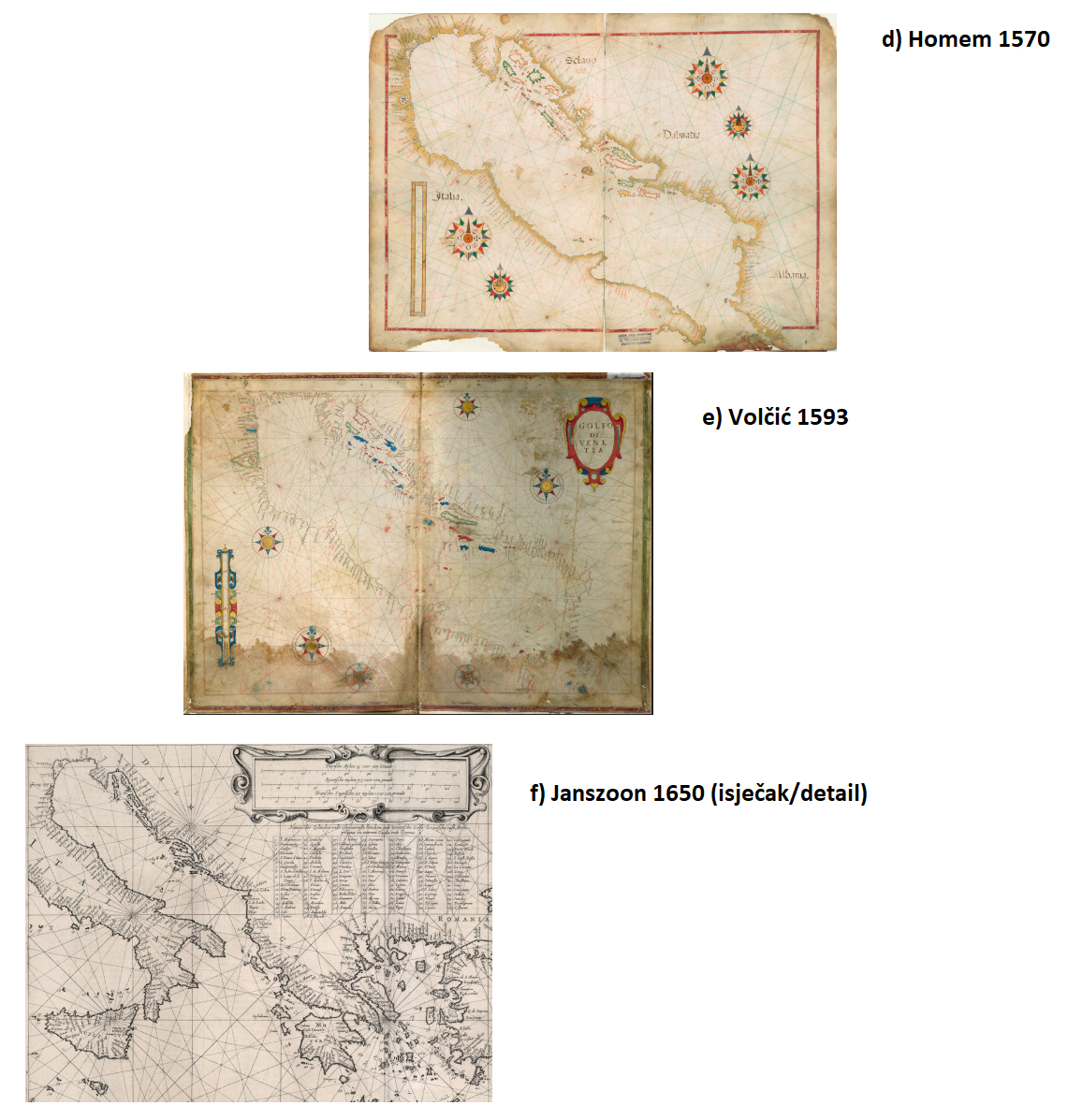

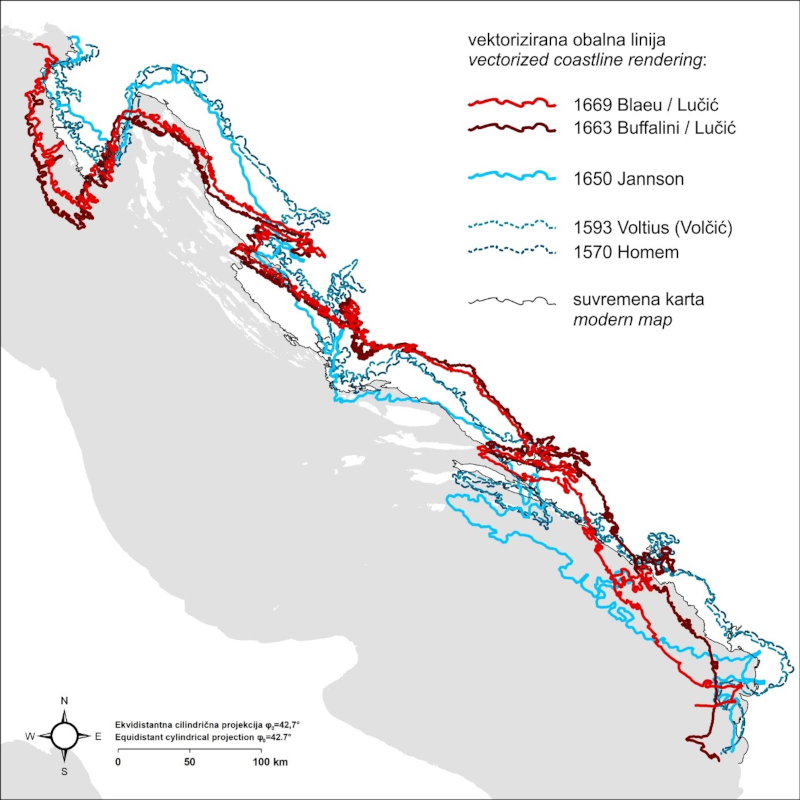

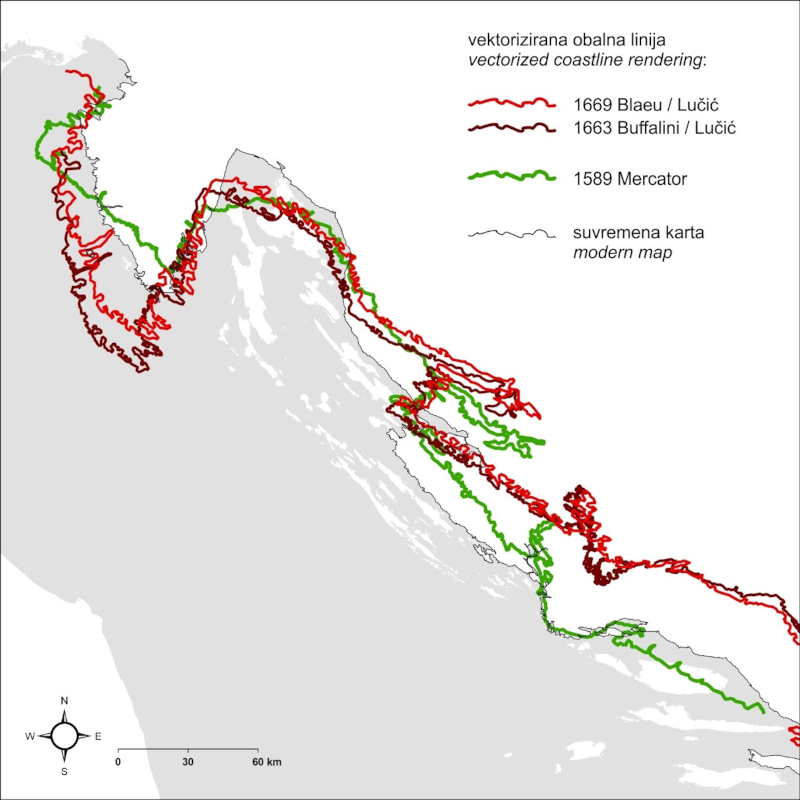

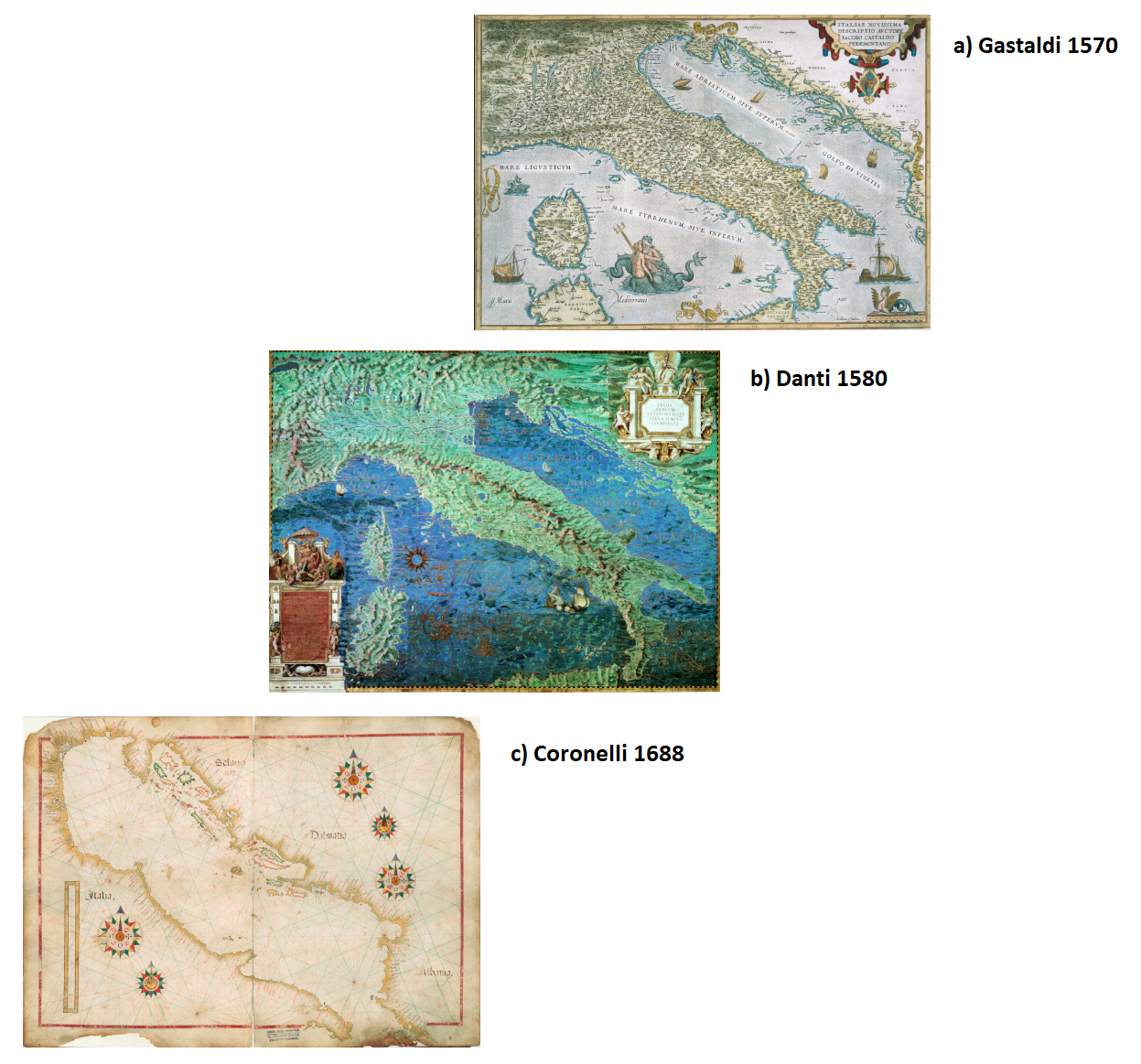

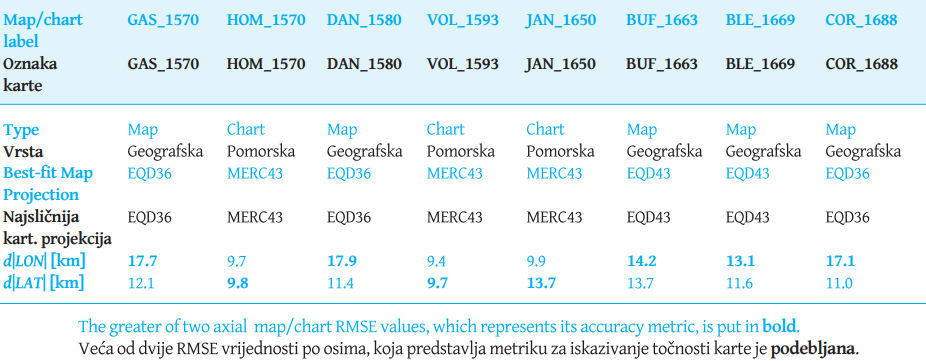

The coastal part of the 1663 map of Illyricum was metrically compared with the rendering of the coastline on the 1669 map of 'Today's Illyricum' (published by the Dutch publisher and cartographer, Joan Blaeu) and on a selected sample of maps and charts made at the end of the 16th and during the 17th century (Table 1,Figure 3). Two from each group of maps and charts were produced approximately a century earlier (GAS_1570, HOM_1570, DAN_1580 and VOL_1593), and one from each group (JAN_1650 and COR_1688) was produced in approximately the same period as the map of Illyricum (BUF_1663 and BLA_1669).[2]

Table 1. Research sample of maps and charts / Tablica 1. Uzorak geografskih i pomorskih karata

Maps from the sample were georeferenced using the Helmert transformation (Modenov and Parkhomenko, 1965: 77–93) on a sample of points that was standardized with regard to the coverage of the Adriatic Sea on them. For georeferencing maps showing the entire Adriatic Sea, 45 identical points were determined; on the DAN_1580 map, 39 (of the 45) points were determined; while the maps of Illyricum, which show only the eastern part of the Adriatic Sea, were georeferenced on the basis of 20 (of the 45) identical points. The geometric accuracy of the maps was determined on the basis of the deviation (residual) of their identical points in relation to their corresponding reference points and is expressed using root mean squared error (RMSE) (Loomer, 1987: 113;Bevington and Robinson, 2003: 98–114;Jenny and Hurni, 2011: 403–405;Nicolai, 2014: 209–210;Penzkofer, 2016: 27–28), in which the greater of the two values of error, one per axis, is used as a measure of accuracy. In addition to georeferencing the maps, the coastline of the mainland stretching from the Bay of Trieste to Durrës (corresponding to the coverage of the eastern part of the Adriatic Sea on the maps of Illyricum) was vectorized on all the maps in the sample, in order to make it easier to determine whether certain types of cartographic templates were used, potentially, in creating the rendering of the east coast of the Adriatic Sea on the 1663 map of Illyricum, and whether improvements in the quality of the geographic content, in relation to earlier cartographic realizations, were achieved.

The nautical charts in the selected sample (Table 1) showed the highest accuracy in comparison with the Mercator projection, in which deformations in representation of distance are least when it is set with a standard parallel of φ0=42.7° (MERC43), which is approximately the central parallel for the Adriatic Sea basin.[3] Intervals of one degree of longitude (LON) and latitude (LAT) on the graticules on the three maps have a ratio (LON/LAT) of approximately 0.8° across the entire field of the map, which indicates that they were made in a normal equidistant cylindrical projection with standard parallel φ0=36° (EQD36), which corresponds to the central parallel of the Mediterranean Sea, and which was used by Marinus of Tyre for his maps of the ecumene (Snyder 1993: 6,Breggren and Jones 2000: 33–34).

Figure 3. Selected maps and charts of the 16th and 17th centuries with which the map of Illyricum of 1663 is compared: a – Gastaldi 1570, b – Danti 1580, c – Coronelli 1688, d – Homem 1570, e – Volčić 1593, f – Janszoon 1650 (detail) / Slika 3. Odabrane geografske i pomorske karte 16. i 17. st. s kojima je uspoređena Karta Ilirika iz 1663.: a – Gastaldi 1570, b – Danti 1580, c – Coronelli 1688, d – Homem 1570, e – Volčić 1593, f – Janszoon 1650 (isječak)

On the map of Illyricum printed in the atlas by Joan Blaeu (BLA_1669), this ratio is 0.73, which corresponds to a normal equidistant cylindrical projection with standard parallel φ0=42.8° (EQD43)[4]. The 1663 map of Illyricum (BUF_1663) does not contain the graticule, but the coastline rendering on it is visibly, even at a glance, very similar to the rendering on the 1668 map of Illyricum. On this basis, it was assessed that both maps were made in the same projection, and map BUF_1663 was also georeferenced to a modern map given in the EQD43 projection.

In georeferencing the maps, it was determined that they show the highest accuracy (lowest RMSE values of geometric errors) precisely in comparison with these projections. Navigational charts show a larger mean latitudinal error (RMSE d|LAT|) versus average mean longitudinal error (RMSE d|LON|), while for all the maps in the sample (including the 1663 and 1668 maps of Illyricum), the average errors of longitude are greater (Table 2). Average RMSE d|LON| errors of the two maps of Illyricum are lower than the errors on the other maps by about 3 km, but it is not possible to compare the two sets of maps, since fewer than half the number of identical points were used for georeferencing the maps of Illyricum.[5]

Table 2. The geometric accuracy of coastline renderings on the maps of Illyricum (BUF_1663, BLA_1669) in comparison with coastline renderings on selected older and contemporary maps and charts on which the Adriatic Sea is represented / Tablica 2. Geometrijska točnost prikaza obale na kartama Ilirika (VAT_1663, BLE_1669) u usporedbi s prikazom obale na odabranim starijim i suvremenim geografskim i pomorskim kartama na kojima je prikazano Jadransko more

The rounded average scale of the 1663 map of Illyricum, according to distance measurements on the map and in GIS software (QGIS), is 1:450,000. Measurements of distance were made on five segments – Cape Permantura - Zadar, Zadar - Cape Ploča, Cape Ploča - Cape Lovište (Pelješac), and Cape Lovište - mouth of the River Drim – and compared with their lengths on a modern map in the EQD43 projection at a scale of 1:1 (deformations caused by map projection were taken into account). The standard deviation (SD) amounts to 36,581, i.e. about 8%, with the largest deviation from the average recorded for the southern part (measurement of Cape Lovište - mouth of the River Drim), without which the SD would amount to 27,201, i.e. about 6%. The linear scale on the map is indicated in Italian land miles (Scala di Miglia treara Italiane). It represents a distance of 30 miles and has a total length of 109 mm, and is divided into three larger intervals of 10 miles each (36 mm in length per interval), while one larger interval is further divided into 10 smaller ones (3.6 mm in length), each of which represents one mile. On a georeferenced map, those 30 map miles correspond to a distance of 47.4 km, which would mean that one mile equals 1.58 km – a value that roughly corresponds to one Tuscan mile of 1,654 m (Treese 2018: 145). The scale of Buffalini's map derived exclusively on the basis of the linear scale is 1:434,862.

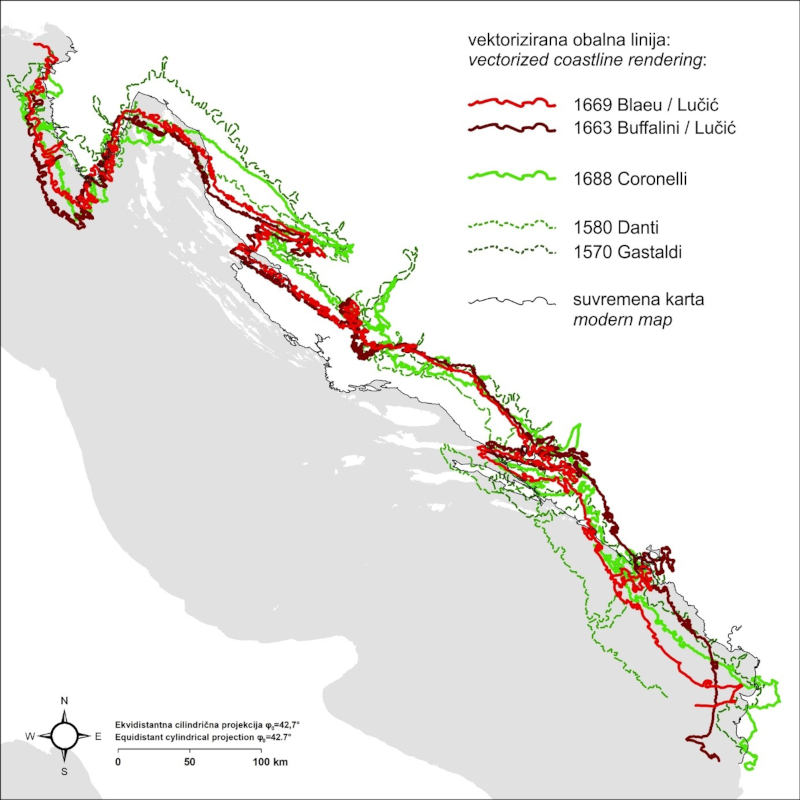

Figure 4. Vectorized renderings of the Eastern Adriatic Sea mainland coastline on the maps of Illyricum (1663, 1669) in comparison with its renderings on the selected maps, two older (1570, 1580) and one contemporary (1688); the vectorized coastline rendering on those three maps is reprojected from EQD36 into EQD43 / Slika 4. Vektorizirana obalna crta istočnog dijela obale kopna Jadranskog mora na kartama Ilirika (1663, 1669) u usporedbi s dvije starije (1570, 1580) i jednom suvremenom (1688) geografskom kartom; vektorizirani prikaz obalne crte na te tri geografske karte reprojiciran je iz EQD36 u EQD43

The representation of the area of Illyricum on the map is rotated by (−35°), with respect to the direction of the sign for north, but during georeferencing of the map it was found that the rotation of the display (Ɵ) is (−27°), which would mean that the north direction on the map has a deviation of (−8°) in relation to the rotation resulting from the conformal transformation of the map in the GIS software. However, on the basis of these values, it is not possible to determine with what accuracy the author performed the rotation of the display, because: a: georeferencing was performed on a sample of only 20 coastal points, and the display of the coast makes up a relatively small part of the total display of area on that map, and b: the accuracy of the coastal part of the map shows positional errors, which probably also exist on the rest of the display, which has not been metrically analysed.

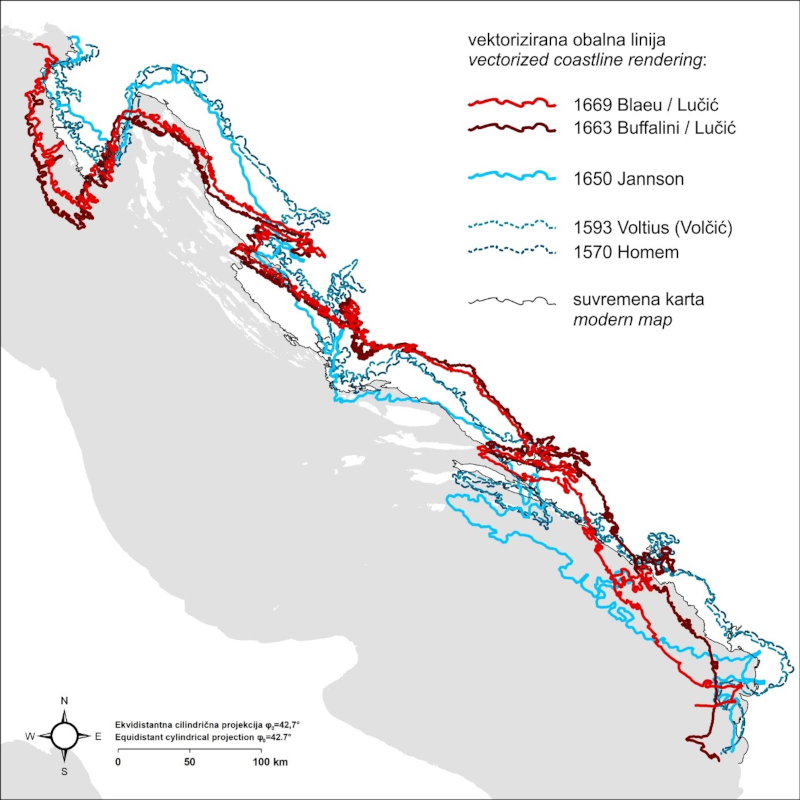

Figure 5. Vectorized renderings of the Eastern Adriatic Sea mainland coastline on the maps of Illyricum (1663, 1669) in comparison with the selected nautical charts, two older (1570, 1593) and one contemporary (1650); the vectorized coastline rendering on those three nautical charts is reprojected from MERC43 into EQD43 / Slika 5. Vektorizirana obalna crta istočnog dijela obale kopna Jadranskog mora na kartama Ilirika (1663, 1669) u usporedbi s dvije starije (1570, 1593) i jednom suvremenom (1650)

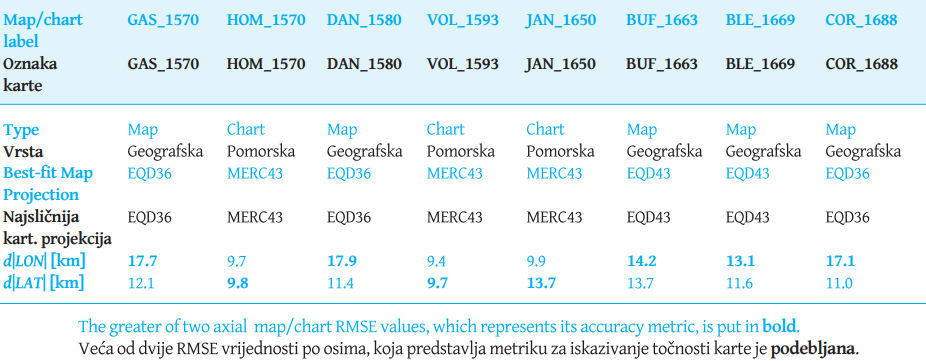

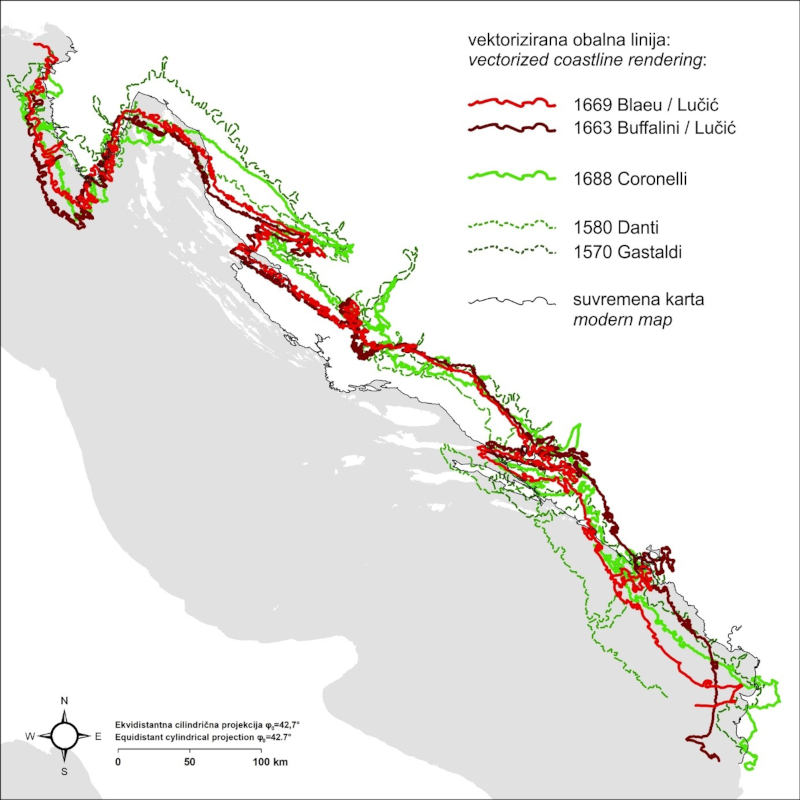

The appearance of the coastline on the 1663 map of Illyricum on most of the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea is extremely similar to its appearance on the 1668 map of Illyricum (like on Blaeu's 1669 edition of the same map). Visible differences exist only in the rendering of the extreme southeast part of the coast, but this difference is caused mostly by a change in the appearance of the peninsula of Pelješac, because of which, on the 1668 (1669) map of Illyricum, there was a relative transposition of the coast south of it in a southerly direction. If the transposition of that segment of the coast is ignored, the far southeast part of the coast is, with the exception of the rendering of the Drim delta, very similarly drawn on both maps.

The maps of Illyricum are most accurate in comparison to the EQD43 projection, while the nautical charts are most accurate in comparison to the MERC43 projection, and the geographic maps are most accurate in comparison to the EQD36 projection. The mainland coastline of the eastern part of the Adriatic Sea was vectorized on all eight maps/charts in the projection relative to which they show the highest geometric accuracy, which is why (for the purpose of comparing the appearance of the coastline on these maps/charts with its appearance on the maps of Illyricum in the same coordinate system) subsequent re-projection was performed of these vector data into the EQD43 system (Figure 4,Figure 5). The rendering of the coast of Istria on the 1663 and 1668 maps of Illyricum is less accurate than its rendering on the maps/charts they were compared to, especially in relation to the rendering of the coast of Istria on the nautical charts. On the other hand, the rendering of the area below Velebit, especially the part between Senj and Karlobag, is shown more reliably on the 1663 and 1668 maps of Illyricum than on the selected examples of maps and charts. The area of northern Dalmatia is most reliably drawn on the three geographic maps (least reliably on the nautical charts). The perception of that part of the coast is very realistic, but it shows deviations in the approximated axis of extension of the coast, while the whole of southern and central Dalmatia is shown similarly to the geographic maps, with the exception of Danti's map of Italia nova, where there are large deviations in this respect. In the preparation of the research, we assumed that that particular map could have had an important influence on the rendering of the coastline on the 1663 map of Illyricum. That map is, in fact, one of the maps in the Gallery of Geographic Maps in the Vatican Palace created in 1581 by cartographer Ignazio Danti. In 1631, Pope Urban VIII (Barberini) charged the Vatican librarian and cartographic erudite, Lukas Holstein, with updating the geographic content of the maps, which Holstein did with regard to the Italia nova map (Fiorani 1996, 128), but the exact extent of his interventions on that map and a number of others is not known. (He did not attend to all the maps in the Gallery.) Given that Stjepan Gradić was appointed advisor to the Sacred Congregation of the Index in 1658, and curator of the Vatican Library in 1661 (Martinović 1983: 14), he certainly had access to the Gallery, where he could consult Danti's maps (with Holstein's additions). Access to the Gallery was also possible for Buffalini, thanks to good connections with the Barberini family (cf. Gudelj 2016: 193). However, cartometric analysis did not confirm accordance of the content of the Italia nova map with the 1663 map of Illyricum. Nor is the rendering of the coastline on the 1663 and 1668 maps of Illyricum similar to the rendering of the same area on the nautical charts of the sample, which indicates that Lučić did not use them as graphic templates for creating the maps of Illyricum.

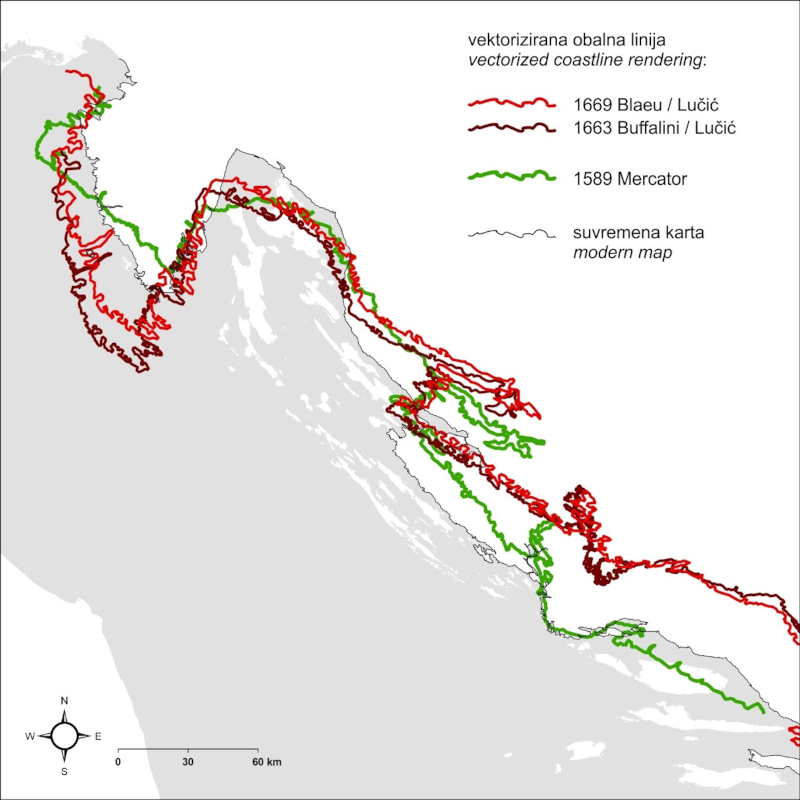

However, some traces clearly point to some of the cartographic sources used. Among others, there was most likely the original 1589 map of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia by Mercator, numerous versions of which were printed, and thus widely available even in the 17th century. Mercator's traces were not noticeable in the rendering of the coastline as one of the key geographic contents that greatly define the appearance of the depicted region (Figure 6), but was recorded in his mistake of showing Zagreb twice: Agram at the proper location, and Zagrabije near the confluence of the Kupa and Sava, near Sisak. It is odd that Lučić, or any of his associates, did not notice and then correct this mistake. Evidently, they, like many other cartographers of the time, were strongly influenced by authorities in the field of geography and cartography on the one hand; and, on the other, they uncritically compiled various data sources without checking whether inconsistent mosaics of content thus arose. Therefore, his contemporary Stjepan Glavač was correct in writing, in the dedicatory cartouche of his map of Croatia (in a narrower sense) printed in 1673: “When I think that all the neighbouring provinces have maps made (as I was partly taught by experience of travel, and partly by reliable connections with learned people from those areas), the description of our Homeland alone is composed so superficially that it hardly contains any true notion. For much of it lies in the wrong place, much that is worthy of mention has been omitted, and much has been somewhat ludicrously crammed in; to remain silent about much else, it is enough to see how it has been concluded that Agram and Zagreb are two cities, two miles apart, which is not true at all, the only difference being that one name is German and the other Latin” (translated fromMarković 1998, 381–382). At the same time, it should be pointed out that the spatial scope of “our Homeland”, i.e. Croatia as perceived and depicted by Glavač accords with what was called, in early modern vocabulary, the remains of the remains of the once great and glorious Kingdom of Croatia (reliquiae reliquiarum olim magni et inclyti regni Croatiae), and not the entire area shown on the 1663 map of Illyricum.

Figure 6. Vectorized renderings of the Eastern Adriatic Sea mainland coastline on the maps of Illyricum (1663, 1669) in comparison with its rendering on Mercator's map (1589); the vectorized coastline rendering on all three geographic maps is reprojected from EQD36 into EQD43 / Slika 6. Vektorizirana obalna crta istočnog dijela obale kopna Jadranskog mora na kartama Ilirika (1663, 1669) u usporedbi s njezinim prikazom na Mercatorovoj karti (1589); vektorizirani prikaz obalne crte na sve tri geografske karte reprojiciran je iz EQD36 u EQD43

4 Conclusion

Through research on the original map of Illyricum, which is kept in the Pontifical Croatian College of St Jerome in Rome, Ivan Lučić was confirmed as one of the key (co)authors of the map. Lučić correctly demurs, claiming only that his map was an attempt to correct many “mistakes” in the depiction of the same area, but he encouraged “whoever it pleases to look there at correctly drawn positions and to add those corrections that seem to him to be more accurate than what I have printed”. Despite the progress in the presentation of certain geographical elements, Lučić (as well as other co-authors) still did not know the geographical features of the area depicted well enough, for he certainly did not travel throughout it, let alone make topographical observations or organize and carry out metrologically demanding surveying procedures. The co-authors of the map of the four Croatian spatial units with the politico-legal categories of kingdoms – Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia and Bosnia – thus remained within the framework of a frequently-applied method in shaping the content of the small-scale maps that were made in the second half of the 17th century: on the basis of a compilation of existing maps, those elements of the geographic content that the co-authors knew well, either empirically or on the basis of available archival documentation, were supplemented or altered in places. With regard to their scientific focus, although very broad, Lučić and other participants in that cartographic endeavour could not make any improvements from a geodetic point of view, but empirically they still rendered the coastline of the northeast part of the Adriatic significantly better than had been shown on maps and charts until that time. It is possible to establish that the most important co-authorial contribution to the map of Illyricum drawn by Buffalini was that of Lučić, and following Marković and Gudelj, the contributions of Gradić and other members of the Croatian community of St Jerome in Rome cannot be ignored, either. In view of Lučić's contributions to the creation of the maps of Illyricum, it is not justifiable to attribute the 1663 map exclusively to Buffalini, or the 1668 map (and later editions) exclusively to Blaeu. When attributing these maps, it is most appropriate to follow the words of Lučić from his work 'Historical testimonies about Trogir' – which are similar, in key parts, to the text in the cartouche of the 1663 map – i.e. to call that map Lučić's map of Illyricum, of which the prototype was drawn by Buffalini in 1663, and the printed version was produced by Blaeu in 1668.

Note

This paper is the result of research carried out within scientific project IP-2020-02-5339, Early Modern Nautical Charts of the Adriatic Sea: Source of Knowledge, Means of Navigation and Medium of Communication, funded by the Croatian Science Foundation.

1. Uvod

U Papinskom hrvatskom zavodu Sv. Jeronima u Rimu čuva se rukopisna geografska karta hrvatskih zemalja koju je nacrtao arhitekt i geograf Pietro Andrea Buffalini iz Rima 1663. Karta izrađena je u dimenzijama 155 cm x 100 cm (vanjske dimenzije okvira iznose 190 cm x 125 cm). Ne sadrži prikaz stupanjske mreže, već linearno mjerilo i pojednostavljeni prikaz smjera sjevera (označen stiliziranim znakom cvijeta ljiljana) i istoka (označen znakom križa) na plavom krugu. Premda karta nema naslov, u kartuši je opisan njezin sadržaj i njezina namjena: Congregatio Nationis Illyricae sicuti instituta fuit ab Illyricis ex Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosna et Slauonia in Urbem confluentibus; ita eorundem Regnorum Nationales tantum, vel Oriundi, Slavonica tamen lingua loquentes, iurium ipsarum participes esse debent: ut constat ex Decisione Sacrae Rotae diei X Decembris MDCLV coram R.P.D. Priolo: Ideo ad evitandas aequivocationes vel fraudes haec quatuor Regna, fines que eorum delineati fuerunt ut possint distingui quae loca includi, quaeue excludi debeant. [1] Riječ je, dakle, o kartografskom prikazu četiriju provincija – Dalmacije, Hrvatske, Slavonije i Bosne – koja se podudaraju s geografskim imenom Ilirika, i iz kojih u papinski zavod Sv. Jeronima imaju pravo dolaziti oni koji se mogu služiti pravima Zbora ilirske (hrvatske) nacije. To je prva poznata novovjekovna karta na kojoj su prikazane sve velike prostorne cjeline koje su u to doba bile naseljene hrvatskim stanovništvom, onim koje se služilo hrvatskim jezikom (Slavonica lingua) (Mlinarić i dr. 2012). U vrijeme izrade karte Ilirika 1663. prikazani prostor bio je politički fragmentiran između tri države: Habsburške Monarhije, Osmanskog Carstva i Mletačke Republike, a samo je prostor Dubrovačke Republike funkcionalno prakticirao visok stupanj političke neovisnosti. Na karti se, međutim, ne zrcale partikularni imperijalni interesi i s njima povezani narativi, već svijest o pripadnosti istom nacionalnom, odnosno jezičnom korpusu, na podlozi antičke tradicije uokvirenom rimskodobnim imenom Ilirika. Formalno gledajući, riječ je o anakronizmu, ali i o funkcionalno spretnom odabiru imena kojim je bilo moguće prostorno obuhvatiti različite regionalne entitete. Taj je prostor omeđen u odnosu na susjedne europske regije granicom uz koju je ispisan tekst: Confini delle quatro prouincie Illyriche. Unutar te granice nisu prikazani svi prostori koji su tada bili naseljeni Hrvatima. Naime, izvan granica ostali su Istra, Međimurje i hrvatski dio Baranje. Za izdvajanje Međimurja već je Ivan Črnčić, koji je prvi ukratko opisao kartu, ponudio razlog: „Valja da su se bojali grada Strigova gdje ono tvrde, da se je rodio sv. Jeronim“ (Črnčić 1886: 69–70). Naime, i u doba izrade karte bila je živa rasprava o lokaciji antičkog Stridona koji se po navodima samoga Jeronima, nalazio na granici Dalmacije i Panonije, a pobornicima Marulićeve teze da je Jeronimov Stridon potrebno poistovjetiti sa Sidronom na Ptolemejevoj Petoj karti Europe, zasigurno je bilo teško Međimurje „privući“ toj granici (Bulić 1920,Suić 1986,Margetić 2002).

Karta Ilirika iz 1663. (slika 1) je jedna od najstarijih karata cijelog područja današnje Hrvatske kod kojih je moguće nedvojbeno precizno utvrditi njezinu utilitarnu svrhu i detektirati njezine korisnike: određivanje prava na korištenje usluga hospicija, odnosno zavoda za Hrvate katolike u Rimu po odredbi visoke sudske vlasti Papinske Države onima koji se nalaze unutar granica četiriju provincija Ilirika: Dalmacije, Hrvatske, Slavonije i Bosne.

U znanstvenoj literaturi već je obavljena sažeta, ali sadržajna kartografska analiza karte Ilirika iz 1663. (Črnčić 1886,Škrivanić 1968,Marković 1993), a analiziran je i crkveno-pravni i povijesno-zemljopisni kontekst njezina nastanka (Mlinarić i dr. 2012). Kao prilog dosadašnjim istraživanjima karte Ilirika iz 1663. kartometrijski je uspoređen prikaz obale na toj karti s prikazom obale na odabranim geografskim i pomorskim kartama s kraja 16. i prve polovine 17. st. Na temelju te analize nastojali smo utvrditi jesu li odabrane karte služile kao predlošci za izradu karte Ilirika iz 1663. i je li je s tom kartom učinjen kvalitativni iskorak u prikazivanju sjeveroistočne obale Jadrana. K tome, na temelju istraživanja dostupnih pisanih izvora podataka nastojali smo pridonijeti raspravi o (ko)autorskim doprinosima u oblikovanju geografskog sadržaja te rukopisne karte Ilirika.

2. Autorstvo karte Ilirika iz 1663.

Doprinos Stjepana Gradića izradi karte

S obzirom na to da je u vrijeme izrade rukopisne karte Ilirika iz 1663. predsjednik Bratovštine Sv. Jeronima u Rimu bio Dubrovčanin Stjepan Gradić (Stefano Gradi, Stephanus Gradius) (Krasić 1987: 92), pojedini znanstvenici logično su smatrali da je upravo Gradić Buffaliniju dao potrebne geografske podatke i da je Gradić ne samo zakonski predstavnik naručitelja nego i autor karte koju je u tehničkom smislu izradio Buffalini. K tome, Gradićeva suradnja s Buffalinijem bila je vrlo plodonosna i na drugim područjima. Možda najvažnije ostvarenje te suradnje je Buffalinijev angažman u projektiranju nove dubrovačke katedrale koja je, po nacrtu toga rimskog arhitekta, sagrađena na mjestu katedrale porušene u potresu koji je Dubrovnik pogodio 1667. (Marković 2012: 83-92). K tome, prema Buffalinijevu projektu proširena je zgrada Zavoda sv. Jeronima u Rimu (Gudelj 2014: 375).

U dosadašnjim istraživanjima znanstvenici su polazili od podataka koje je prvi iznio Črnčić pišući o problemu korištenja imena Slovjenin i Ilir u gostinjcu Sv. Jeronima u Rimu (Črnčić 1886: 69). Neposredan povod za izradu karte Ilirika bio je spor oko toga tko može biti član Zavoda Sv. Jeronima u Rimu. Sveta Rota je 1655. presudila da se pod Ilirikom trebaju smatrati Dalmacija, Hrvatska, Bosna i Slavonija (Črnčić 1886: 64–66). Bratovština Sv. Jeronima u Rimu naručila je izradu karte tog prostora 6. listopada 1659, a rukopisnu kartu nacrtao je rimski arhitekt Pietro Andrea Buffalini 2. rujna 1663. i za to mu je plaćeno 36 škuda. Črnčić je dodao da je „slikara“ Buffalinija tijekom izrade karte „putio“ predsjednik Bratovštine opat Stjepan Gradić, Dubrovčanin koji je bio kustos Vatikanske knjižnice i član Akademije švedske kraljice Kristine (Črnčić 1886: 69).

Neupitno je da je Gradić, s obzirom na svoj položaj u Bratovštini Sv. Jeronima, bio presudan za odabir osobe koja će nacrtati kartu. Međutim, postavlja se pitanje zašto je odabran baš Buffalini. Pietro Andrea Buffalini pripadao je akademiji talijanskih umjetnika u Rimu pod titulom sv. Luke (Accademia de i Pittori e Scultori di Roma), čija je ustanova odobrena papinskim breveom 1577. godine. U katalogu iz 1696. godine zaveden je kao Pietro Andrea Buffalini Architetto te mu je pored imena naznačen datum 16. lipnja 1673. godine, datum njegova pristupanja akademiji (Ghezzi 1696: 51,Gudelj 2016: 193). Buffalini je u znanstvenoj literaturi spomenut i kao profesor geografije na rimskome učilištu La Sapienza (Bedini 2021, 281), što potvrđuje i znanstvena rasprava o promatranju nebeskih tijela iz 17. stoljeća u kojoj se vlastoručno potpisao: „Io Pietro Andrea Bufalini Proffesore di Geografia mano propria“ (Buffalini 1666: 38).

Črnčićevim tragom Gradićev doprinos izradi karte istakao je i Gavro Škrivanić navodeći da je karta izrađena „po zamisli i uputstvima Stiepa Gradića“ (Škrivanić 1968: 273), dok je na drugom mjestu naziva „Gradićevom kartom Ilirije – Dalmacije“ (Škrivanić 1968: 276), koja je „prvorazredni izvor za istorijska i istorijsko-geografska proučavanja toga vremena“ (Škrivanić 1968: 276). Na isti način kartu su Gradiću atribuirali Ćosić i N. Glamuzina, ponavljajući Črnčićeve i Gavranovićeve navode da je Buffalini kartu izradio po Gradićevim (Gradijevim) uputama i nazivajući tu kartu „Gradijevom kartom“ (Ćosić i Glamuzina 2018: 207). Marković je smatrao da kartu Ilirika iz hrvatskog zavodg Sv. Jeronima u Rimu nije ispravno nazivati Gradićevom kartom kako je to učinio Škrivanić „već je sinteza zajedničkog rada članova Zavoda s kartografom Buffalinijem“ (Marković 1993: 175–182, bilješka 12). Isto je ponovila i Slukan Altić, dodajući da Gradić i suradnici „pri izradi karte nisu precrtavali već postojeće karte, nego je svaki član Zavoda s obzirom na svoje podrijetlo sudjelovao u ucrtavanju tog dijela Ilirika (Slukan Altić 2003: 130). U prilog tomu može se istaknuti činjenica da je Buffalini tijekom izrade karte stanovao u kući br. 17 u vlasništvu Bratovštine sv. Jeronima (Gudelj 2016: 191). Marković je naveo da je Ivan Lučić (Giovanni Lucio, Johannes Lucius) tu kartu (koju je nacrtao Buffalini) koristio kao predložak za kartu koja je objavljena u trećem izdanju knjige De regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae („O kraljevstvu Dalmacije i Hrvatske“) 1668. 1668 (Marković 1993: 182), dok je Slukan Altić utvrdila da je riječ „o preuzetoj i dotjeranoj Gradićevoj karti“ (Slukan Altić 2003: 132). Sudeći po podudarnosti geografskog sadržaja, neupitno je da je Lučićeva karta Illyricum hodiernum iz 1668. vrlo nalik rukopisnoj karti istoga prostora iz 1663. Naša kartometrijska analiza potvrdila je da je riječ o gotovo faksimilom prikazu obalne crte sjeveroistočne jadranske obale koji se razlikuje od svih starijih i istodobnih prikaza te obale na geografskim i pomorskim kartama.

Doprinos Ivana Lučića Trogiranina izradi karte

Recentna arhivska istraživanja Jasenke Gudelj rezultirala su njezinom tvrdnjom da je „karta načinjena s očiglednom pomoći Gradića i trogirskoga povjesničara Ivana Lučića“ (Gudelj 2016: 191). Naime, u vrijeme izrade karte Ilirika iz 1663., u Zavodu sv. Jeronima u Rimu boravio je i Ivan Lučić Trogiranin, koji je Gradića naslijedio na mjestu prvoga čovjeka u Bratovštini sv. Jeronima (Škrivanić 1968: 273). Baveći se ponajprije kartom Ilirika tiskanom 1668. i objavljenom u knjizi „O kraljevstvu Dalmacije i Hrvatske“,Mlinarić i dr. (2012) i za rukopisnu kartu Ilirika iz 1663. navode, oslanjajući se na podudarnost geografskog sadržaja, kako je riječ o Lučićevom kartografskom ostvarenju. U prilog Lučićevom autorstvu karte ili barem presudnom koautorskom doprinosu u oblikovanju njezina geografskog sadržaja idu njegove riječi napisane u djelu Memorie istoriche di Tragurio ora detto Traù („Povijesna svjedočanstva o Trogiru“), objavljenom 1673.: „Tko na njoj bolje pogleda razne položaje vidjet će da na dosada tiskanim kartama ima mnogo pogrešaka i to ne samo u vezi s trogirskim teritorijem, već i sa cijelom Pokrajinom. Da bih to ispravio, ja sam načinio novu kartu današnjeg Ilirika koji se sastoji od četiri pokrajine: Dalmacije, Hrvatske, Bosne i Slavonije, i raznim sam nacrtima i opaskama ispravio najbolje što sam mogao dosada tiskane pogreške, potičući svakoga koga to veseli da tamo gleda točno nacrtane položaje i da doda one ispravke koji mu se budu činili točnijim od onih što sam ih ja tiskao“ (Lučić 1673, translated 1979: 706). Na to je među hrvatskim povjesničarima kartografije prvi upozorio Kozličić, koji je istakao da Lučićeve karte nemaju pravih analogija u povijesti kartografiranja istočnog Jadrana (Kozličić 1995: 218, 220).

Lučić je bio svjestan činjenice da je na toj karti Ilirika dao uopćen prikaz bez dovoljno detalja, pa je u pismo upućenom Šibenčaninu Danijelu Difniku 1676. dao uputu da svom bratu (Franji), koji je pripremao opsežnu Historia della guerra di Dalmatia tra Venetiani e Turchi („Povijest Kandijskog rata u Dalmaciji između Mlečana i Turaka“), prenese prijedlog da svoje djelo dopuni s kartom Dalmacije, detaljnijom nego što je njegova, bar za područje Zadra, Šibenika, Trogira, Splita i Omiša (Kečkemet 1986: 7–52). Lučić je u prvom izdanju svojega djela „O kraljevstvu Dalmacije i Hrvatske“ objavio pet preglednih i vrlo poopćenih karata primorskog dijela današnje Hrvatske, dok je tek u trećem izdanju te knjige objavljenom 1668. naknadno uvrštena karta „Današnjeg Ilirika“, koju je za tisak priredio nizozemski izdavač i kartograf Joan Blaeu. Blaeu je istu kartu zatim 1669. objavio i u atlasu Atlas Maior / Geographia Blaviana (slika 2). Blaeuov doprinos bio je nalik onom Buffalinijevom: Lučić (i drugi koautori) nije se bavio tehničkim dijelom izrade karata već je bio ključan u definiranju njezina geografskog sadržaja.

Objavljivanje tiskane karte „Današnjeg Ilirika“ omogućilo je njezinu diseminaciju širom Europe. Premda je njezin komunikacijski potencijal bio velik, uskoro su je zamijenile karte s prikazima istog prostora koje su izradili Giacomo Cantelli i Vincenzo Maria Coronelli. Coronellijeve karte postale su predložak koji su, uz neznatne preinake, za tisak priređivali brojni europski kartografi tijekom 18. st. pa su one postale model za oblikovanje geografske percepcije i kartografsko prikazivanje prostora koji se danas nalazi u sastavu Republike Hrvatske u epohi koja je prethodila sustavnim geodetskim izmjerama. S druge strane, karta Ilirika iz 1663. postala je jednom od najdugovječnijih permanentno korištenih rukopisnih karata – njezin se original, uokviren i obložen staklom poput slike, i danas se nalazi na zidu u posebnoj prostoriji Papinskoga hrvatskog zavoda Sv. Jeronima u Rimu.

3. Geometrijska obilježja obalnog dijela karte

Obalni dio Karte Ilirika iz 1663. metrički je uspoređen s prikazom obale na karti „Današnjeg Ilirika“ iz 1669. (u izdanju nizozemskog izdavača i kartografa Joana Blaeua) i na odabranom uzorku geografskih i pomorskih karata izrađenih krajem 16. st. i tijekom 17. stoljeća (tablica 1,slika 3). Po dvije karte iz svake grupe izrađene su približno jedno stoljeće ranije (GAS_1570, HOM_1570, DAN_1580 i VOL_1593), a po jedna iz svake grupe (JAN_1650 i COR_1688) je izrađena u približno sličnom razdoblju kao i karte Ilirika (BUF_1663 i BLA_1669).[2]

Karte iz uzorka georeferencirane su korištenjem Helmertove transformacije (Modenov, Parkhomenko, 1965: 77–93)na uzorku točaka koji je standardiziran s obzirom na obuhvat prikaza Jadranskog mora na njima. Za georeferenciranje karata na kojima je prikazano čitavo Jadransko more određeno je 45 identičnih točaka, na karti DAN_1580 određeno je 39 (od 45) točaka, dok su karte Ilirika, na kojima je prikazan samo istočni dio Jadranskog mora, georeferencirane na temelju 20 (od 45) identičnih točaka. Geometrijska točnost karata određena je na temelju odstupanja (reziduala) njihovih identičnih točaka u odnosu na pripadajuće im referentne točke i izražena je s pomoću srednje kvadratne pogreške (RMSE – root-mean-square error) (Loomer, 1987: 113;Bevington i Robinson, 2003: 98–114;Jenny i Hurni, 2011: 403–405;Nicolai, 2014: 209–210;Penzkofer, 2016: 27–28), pri čemu se kao mjera točnosti koristi veća od dvije vrijednosti pogreške po osima. Osim georeferenciranja karata, na svim kartama iz uzorka vektorizirana je obalna crta kopna na potezu od Tršćanskog zaljeva do Drača (koji odgovara obuhvatu prikaza istočnog dijela Jadranskog mora na kartama Ilirika), kako bi se lakše utvrdilo li određeni tipovi kartografskih predložaka potencijalno bili korišteni za izradu prikaza istočne obale Jadranskog mora na karti Ilirika iz 1663. te jesu li postignuta unaprjeđenja kvalitete geografskog sadržaja u odnosu na ranija kartografska ostvarenja.

Pomorske karte iz odabranog uzorka sample (tablica 1) pokazale su najveću točnost u odnosu na Mercatorovu projekciju, pri čemu su, kada je zadana sa standardnom paralelom φ0=42,7° (MERC43), što je približno srednja paralela za bazen Jadranskog mora, deformacije prikaza duljina najmanje[3]. Intervali od jednog stupnja geografske dužine (LON) i širine (LAT) na stupanjskim mrežama na trima geografskim kartama imaju omjer (LON/LAT) od otprilike 0,8° po čitavom polju karte, što ukazuje na to da su izrađene u uspravnoj ekvidistantnoj cilindričnoj projekciji sa standardnom paralelom φ0=36° (EQD36), koja odgovara srednjoj paraleli Sredozemnog mora, a koju je za svoje karte ekumene koristio Marin iz Tira (Snyder 1993: 6,Breggren i Jones 2000: 33–34).

Na karti Ilirika koju je u atlasu tiskao Joan Blaeu (BLA_1669), taj omjer iznosi 0,73, što odgovara uspravnoj ekvidistantnoj cilindričnoj projekciji sa standardnom paralelom φ0=42,8° (EQD43)[4]. Karta Ilirika iz 1663. (BUF_1663) ne sadrži prikaz stupanjske mreže, no prikaz obalne crte na njoj je već na razini opažanja vidljivo vrlo sličan prikazu na karti Ilirika iz 1668. Na temelju toga procijenjeno je da su obje karte izrađene u istoj projekciji te je karta BUF_1663 također georeferencirana na suvremenu kartu zadanu u projekciji EQD43.

Georeferenciranjem karata utvrđeno je da pokazuju najveću točnost (najmanje RMSE vrijednosti geometrijskih pogrešaka) upravo u usporedbi s tim projekcijama. Pomorske karte pokazuju veću prosječnu pogrešku geografske širine (RMSE d|LAT|) naspram prosječne pogreške geografske dužine (RMSE d|LON|), dok su kod svih geografskih karata iz uzorka (uključujući karte Ilirika iz 1663. i 1668.) prosječne pogreške geografske dužine veće (tablica 2). Prosječne RMSE d|LON| pogreške dviju karata Ilirika razmjerno su niže od pogrešaka na ostalim geografskim kartama za oko 3 km, no ta dva skupa karata nije moguće usporediti zbog više od dvostruko manjeg broja identičnih točaka upotrjebljenih za georeferenciranje karata Ilirika.[5]

Zaokruženo prosječno mjerilo karte Ilirika iz 1663. prema mjerenjima udaljenosti na karti i u GIS softveru (QGIS) iznosi 1:450 000. Mjerenja duljina izvršena su na pet segmenata; Rt Permantura – Zadar, Zadar – Rt Ploča, Rt Ploča – Rt Lovište (Pelješac) i Rt Lovište – ušće rijeke Drim i uspoređena s njihovim duljinama na suvremenoj karti u EQD43 projekciji u mjerilu 1:1 (u obzir su uzete deformacije uvjetovane projekcijom). Standardna devijacija (SD) pritom iznosi 36.581, tj. oko 8%, pri čemu je najveće odstupanje od prosjeka zabilježeno za južni dio (mjerenje Rt Lovište – ušće rijeke Drim), bez kojeg bi SD iznosila 27.201, tj. oko 6%. Linearno mjerilo na karti naznačeno je u talijanskim kopnenim miljama (Scala di Miglia treara Italiane). Predstavlja udaljenost od 30 milja i ukupne je duljine 109 mm, a podijeljeno je na tri veća intervala od po 10 milja (36 mm duljine po intervalu), dok je jedan veći interval dodatno podijeljen na 10 manjih (3,6 mm duljine), od kojih svaki predstavlja po jednu milju. Na georeferenciranoj karti tih 30 milja s karte odgovara udaljenosti od 47,4 km, što bi značilo da je jedna milja jednaka 1,58 km – vrijednost koja približno odgovara jednoj toskanskoj milji od 1.654 m (Treese 2018: 145). Mjerilo Bufallinijeve karte izvedeno isključivo na temelju linearnog mjerila iznosi 1: 434 862.

Prikaz prostora Ilirika na karti je, s obzirom na usmjerenje oznake sjevera zarotiran za (−35°), no prilikom georeferenciranja karte ustanovljeno je da rotacija prikaza (Ɵ) iznosi (−27°), što bi značilo da smjer sjevera na karti ima otklon od (−9°) u odnosu na rotaciju proizašlu iz konformne transformacije karte u GIS softveru. Međutim, na temelju tih vrijednosti nije moguće odrediti s kolikom je točnošću autor izveo rotaciju prikaza jer: a: georeferenciranje je izvedeno na uzorku od samo 20 obalnih točaka, a prikaz obale čini manji dio ukupnog prikaza prostora na toj karti i b: točnost obalnog dijela karte pokazuje pogreške položaja, a koje vjerojatno postoje i na ostatku prikaza koji nije metrički analiziran.

Izgled obalne crte na karti Ilirika iz 1663. na najvećem dijelu istočne obale Jadranskog mora iznimno je sličan njezinom izgledu na karti Ilirika iz 1668. (kao i Blaeuovog izdanja iste karte iz 1669.). Vidljive razlike postoje samo na prikazu krajnjeg jugoistočnog dijela obale, no ta razlika je najvećim dijelom uzrokovana promjenom u izgledu poluotoka Pelješca zbog čega je na karti Ilirika iz 1668. (1669) došlo do relativne transpozicije obale južnije od njega u smjeru juga. Ako se transpozicija tog segmenta obale zanemari, krajnji jugoistočni dio obale je, izuzev prikaza ušća Drima, vrlo slično iscrtan na obje karte.

Karte Ilirika najtočnije su u odnosu na projekciju EQD43, dok su pomorske karte najtočnije u odnosu na projekciju MERC43, a geografske karte u odnosu na projekciju EQD36. Obalna crta kopna istočnog dijela Jadranskog mora vektorizirana je na svih osam karata u projekciji u odnosu na koju pokazuju najveću geometrijsku točnost, zbog čega je (u svrhu usporedbe izgleda obalne crte na tim kartama s njezinim izgledom na kartama Ilirika u istom koordinatnom sustavu) izvedeno naknadno reprojiciranje tih vektorskih podataka u sustav EQD43 (slika 4,slika 5). Prikaz obale Istre je na kartama Ilirika iz 1663. i 1668. manje točan u odnosu na njegov prikaz na uspoređenim kartama, poglavito u odnosu na prikaz obale Istre na pomorskim kartama. S druge strane, prikaz podvelebitskog prostora, poglavito dijela između Senja i Karlobaga, je na kartama Ilirika iz 1663. i 1668. prikazan vjerodostojnije u odnosu na odabrane primjere geografskih i pomorskih karata. Prostor sjeverne Dalmacije je najvjerodostojnije prikazan na trima geografskim kartama (najmanje vjerodostojno na pomorskim kartama). Percepcija tog dijela obale vrlo je realistična no pokazuje odstupanja u aproksimiranoj osi pružanja obale, dok je čitava južna i srednja Dalmacija prikazana slično kao i na geografskim kartama, izuzev Dantijeve karte Italia nova kod koje u tom pogledu postoje velika odstupanja. U pripremama istraživanja pretpostavili smo da upravo ta karta mogla imati važan utjecaj na prikaz obalne crte na karti Ilirika iz 1663. Naime, ta karta je jedna od karata iz Galerije geografskih karata u Vatikanskoj palači, što ih je 1581. godine izradio kartograf Iganzio Danti. Papa Urban VIII (Barberini) zadužio je 1631. godine vatikanskoga bibliotekara i kartografskoga eruditu Lukasa Holsteina da ažurira geografski sadržaj karata, što je Holstein u pogledu karte Italia nova i obavio (Fiorani 1996, 128), ali nije poznat točan sadržaj njegovih intervencija na toj i još nekolicini karata (nije intervenirao u sve karte iz Galerije). S obzirom na to da je Stjepan Gradić 1658. godine bio imenovan savjetnikom Svete Kongregacije indeksa, a 1661. godine kustosom Vatikanske knjižnice (Martinović 1983: 14), zasigurno je imao pristup Galeriji u kojoj je mogao konzultirati Dantijeve karte (s Holsteinovim dopunama). Pristup Galeriji mogao je ostvariti i Buffalini zahvaljujući dobrim vezama s obitelji Barberini (cf. Gudelj 2016: 193). Međutim, kartometrijska analiza nije potvrdila podudarnost sadržaja karte Italia nova s kartom Ilirika iz 1663. Prikaz obalne crte na kartama Ilirika iz 1663. i 1668. nije sličan ni prikazu istog prostora na pomorskim kartama iz uzorka, što upućuje na to da ih Lučić nije koristio kao grafičke predloške za izradu karata Ilirika.

Međutim, neki tragovi jasno upućuju na neke korištene kartografske izvore. Među ostalim, to je po svoj prilici bio izvornik Mercatorove karte Hrvatske, Dalmacije i Slavonije iz 1589. čije su brojne inačice bile tiskane tako širom dostupne i u 17. st. Mercatorov trag nije uočljiv u prikazu obalne crte kao jednoga od ključnih geografskih sadržaja koji umnogome definiraju izgled prikazanog prostora (Figure 6)[6], već je ostao zabilježen u njegovoj greški dvostrukoga prikazivanja Zagreba: Agrama na stvarnoj lokaciji i Zagrabije u blizini ušća Kupe u Savu kod Siska. Neobično je da Lučić ili bilo tko od njegovih suradnika nisu opazili, a zatim i ispravili tu grešku. Očito su, kao i mnogi drugi tadašnji kartografi, bili pod snažnim utjecajem autoriteta u polju geografije i kartografije, a s druge strane nekritički su kompilirali različite izvore podataka ne provjeravajući dolazi li pritom do nesuvislih sadržajnih mozaika. Stoga je s pravom njegov suvremenik Stjepan Glavač u posvetnoj kartuši svoje karte (uže) Hrvatske tiskane 1673. napisao: „Kada pomislim da sve susjedne pokrajine imaju izrađene zemljovide (kako su me dijelom poučila iskustva s putovanja, a dijelom vjerodostojne veze s učenim ljudima iz tih područja), jedino je opis naše Domovine sastavljen tako površno da jedva u sebi nosi neku istinitu predodžbu. Jer u njemu se mnogo toga nalazi na pogrešnom mjestu, mnogo toga, spomena dostojno, izostavljeno je, mnogo pak toga nagurano je na smiješni način; da prešutim mnogo ostaloga, dovoljno je vidjeti kako se zaključuje da su Agram i Zagreb dva grada, međusobno udaljena dvije milje, što uopće nije točno, već je razlika samo u tome da je jedno ime njemačko, a drugo latinsko“. (prijevodMarković 1998, 381–382). Pritom treba istaknuti da se prostorni obuhvat „naše Domovine“, odnosno Hrvatske kakvom ju je percipirao i prikazao Glavač podudara s onim što se ranonovovjekovnim rječnikom nazivalo ostatcima ostataka nekoć velikoga i slavnoga Hrvatskog Kraljevstva (reliquiae reliquiarum olim magni et inclyti regni Croatiae), a ne cijeli prostor koji je prikazan na karti Ilirika iz 1663.

4. Zaključak

Istraživanjem izvornika karte Ilirika koja se čuva u Papinskom hrvatskom zavodu Sv. Jeronima u Rimu utvrđeno je da je Ivan Lučić jedan od ključnih (ko)autora karte. Lučić se korektno ogradio da je njegova karta pokušaj ispravke mnogih „pogrešaka“ u prikazivanju istoga prostora ali je potakao „svakoga koga to veseli da tamo gleda točno nacrtane položaje i da doda one ispravke koji mu se budu činili točnijim od onih što sam ih ja tiskao“. Unatoč pomacima u prikazivanju pojedinih geografskih elemenata, Lučić (kao ni drugi koautori) ipak nije dovoljno dobro poznavao geografska obilježja prikazanog prostora jer ga zasigurno cijeloga nije proputovao, a kamo li obavio topografska opažanja ili pak organizirao i proveo mjernički zahtjevne postupke izmjere. Koautori karte četiriju hrvatskih prostornih cjelina s državno-pravnim kategorijama kraljevstava – Dalmacije, Hrvatske, Slavonije i Bosne – ostali su stoga u okvirima često primjenjivane metode u oblikovanju sadržaja na kartama sitnoga mjerila koje su se izrađivale u drugoj polovici 17. st.: na temelju kompilacije postojećih karata mjestimično su dopunjeni ili izmijenjeni oni elementi geografskog sadržaja koje su suautori empirijski ili na temelju dostupne arhivske dokumentacije dobro poznavali. S obzirom na njihovu znanstvenu usmjerenost, premda vrlo široku, Lučić i drugi sudionici u tom kartografskom pothvatu nisu ni mogli učiniti iskorake s geodetskog motrišta, ali su empirijski ipak znatno bolje prikazali obalnu crtu na sjeveroistočnom dijelu Jadrana nego li je ona bila prikazivana na dotadašnjim geografskim i pomorskim kartama. Moguće je ustanoviti kako je najvažniji koautorski doprinos karti Ilirika koju je nacrtao Buffalini bio onaj Lučićev, a tragom Markovića i J. Gudelj, ne mogu se zanemariti ni doprinosi Gradića kao i drugih članova svetojeronimovske hrvatske zajednice u Rimu. S obzirom na Lučićeve doprinose izradi karata Ilirika, atribuiranje karte iz 1663. kao isključivo Buffalinijev rad ili karte iz 1668. (i kasnijih izdanja) kao isključivo Blaeuov rad nije opravdano. Pri atribuiranju tih karata najprikladnije je slijediti Lučićeve riječi iz njegova djela „Povijesna svjedočanstva o Trogiru“ koje su u ključnom dijelu slične tekstu u kartuši karte iz 1663., tj. da se ta karta nazove Lučićevom kartom Ilirika čiji je prototip 1663. nacrtao Buffalini, a tiskanu inačicu 1668. priredio Blaeu.

Napomena

Ovaj je rad rezultat istraživanja provedenih u sklopu znanstvenog projekta IP-2020-02-5339 Ranonovovjekovne pomorske karte Jadranskog mora: izvor spoznaja, sredstvo navigacije i medij komunikacije koji financira Hrvatska zaklada za znanost.