UVOD

Protected areas are important places for nature-based tourism and ecotourism (Stojanović et al., 2022), so the increasing surface of these areas is an important factor in the development of tourism. For example, in 1961 protected areas covered 3% of the Earth's surface, while today they cover about 15% of the Earth's surface and about 3% of the oceans (Wearing and Schweinsberg, 2019). The characteristics of tourism in protected areas, as an economic activity, make it an important driver of nature protection. Protected areas, recreation, tourism and visitors show numerous interactions (Leung et al., 2018). Despite the fact that it is often neglected and underestimated, tourism in protected areas is a very significant opportunity to educate visitors about natural values and the great importance of biodiversity. Sustainable activities that bring more visitors to protected areas are raising their environmental awareness, but it is also important that the visitors do not endanger environmental and cultural attractions (Bushell and Bricker, 2016). There are several tools that can be used to educate visitors in protected areas, one of the common ones being the interpretation of natural and cultural values (Hughes and Ballantyne, 2013; Stojanović, 2023).

Interpretation is essentially an educational activity aiming to discover the meaning and different relationships in nature, through the use of original objects, first-hand experience or the use of illustrative media, but in such a way that does not imply only the use of factual information (Tilden, 1957). Interpretation of the environment implies the translation of the professional language of natural sciences and related fields into concepts and ideas that are understandable to people who are not scientists (Ham, 1992). In tourism, interpretation is carried out with the help of simple brochures, ecological-educational trails, short films and slide presentations, guided walks and tours, settings in galleries and museums, as well as in visitor centres (Eagles and McCool, 2002; Newsome et al., 2005). Each of these activities can additionally affect the education of tourists, and as a rule, they can also make tourists accept environmentally friendly norms of behaviour. This is why, in tourism development, education is one of the important strategies in visitor management (Weaver, 2006). Due to the character and importance, in tourism development in protected areas, visitor management also stands out as the management of visitor impacts, thus emphasizing the significance of identifying unacceptable changes occurring as the results of visits (Wearing and Schweinsberg, 2019).

Protected areas and their preserved nature, as the main attribute of the image of Croatia, are an attractive factor that contributes to the intensification of tourist traffic, i.e. the economic and accompanying activities in tourist regions. However, the absurdity is that this also encourages the degradation and even devastation of these areas (Vidaković, 2003; Borojević, 2018). Recently, emphasis has been placed on the sustainability of tourism in Croatian protected areas, which is one of the main development topics in tourism (Carić and Škunca, 2016). Tourism in Croatian protected areas is mainly focused on sports and recreational tourism, ecotourism, nature-based, educational, rural, and cultural tourism (Kreitmeyer, 2018). At the beginning of tourism development, protected areas had insufficient infrastructure for visitors, low environmental efficiency and inadequate visual identity (Martinić, 2010). In particular, promotional and marketing activities were at the very low level, as was the case with knowledge and skills of tourism management, knowledge of the structure and needs of target groups of visitors, and monitoring of the impact of tourism use (Križman Pavlović, 2008; Talić, 2018). During the last ten years, a continuous increase in the number of visitors has been recorded, as well as in the presence of vehicles and additional waste generation in protected areas, which has encouraged a more active role of protected area managers in defining and implementing activities and goals leading to social, environmental and economic sustainability (Duvnjak et al., 2023). Due to various challenges of moderating current activities in protected areas, legislation has been adopted and strategies, plans and management models have been designed (Kožić and Mikulić, 2011). In recent years, and based on comprehensively conducted analyses that have pointed out the shortcomings and deficiencies, numerous projects and programs have been implemented in protected areas, especially those aiming to emphasize the educational-interpretative and content function, and to ensure the sustainability of tourist use through the development of visitor management plans (Telenta, 2023).

Due to the tourist visits’ overall importance for protected areas in the global tourism system and due to the trend of constant growth of tourism in protected areas of Croatia, the aim of this paper is to consider the ways of interpretation in the protected areas, as well as the role of interpretation in nature protection.

METODE

The main task of this paper is to examine the applicability of tools for the interpretation of natural values in Croatian protected areas, since they are crucial for assessing the sustainability of protected area management. Three additional tasks arise from this general one.

Task 1:

The first task was to explore the ways of interpreting and managing visitors in literature recognizable globally, with the aim of identifying all available tools for interpretation of the environment and visitor management. Relevant international literature, i.e. monographs, journals and documents were consulted. Based on this, most important tools for environmental interpretation in protected areas were selected and arranged into five basic groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Environmental interpretation and visitor management tools

Tablica 1. Alati za interpretaciju okoliša i upravljanje posjetiteljima

Source: Authors (based on the literature review)

Task 2:

The next task was about researching the representation of the selected groups of interpretation tools and visitor management within the selected protected areas in Croatia.

Task 3:

The final task was a comparative analysis of the recognized interpretation tools from theory, i.e. of visitor management and the current situation in protected areas of Croatia. Based on these analyses, conclusions were drawn on the current state of the applied interpretation tools in Croatian protected areas and recommendations for future research were defined.

Instrument

The survey research was conducted based on the questionnaire formed for the purpose of this paper, according to the review of available studies considering the issues of the facilities, contents, the existence of the ethical code of conduct and the interpretation of natural resources in protected areas. The first group of questions was about the facilities of protected areas, such as the existence of the visitor center and the accompanying contents, walking paths and organized tours. The next group of questions was about the plans and strategies for further tourism development, with indications of tourism activities that should be prioritized. The third group of questions obtained the items regarding the ethical code of conduct, starting from its existence in protected areas to the manners of its presentation to the visitors. The final group of questions was about the interpretation of natural values in protected areas and the contribution of the quality interpretation to nature protection. Besides successful manners of interpreting the natural values to visitors, the questions were also about monitoring the visitors’ satisfaction.

Uzorak i postupak prikupljanja podataka

The research was conducted in seven protected areas of the Republic of Croatia, which have different levels of protection. The sample was designed to cover all geographic macro-regions at the state level, in order to be able to compare the data of regions where there is mass tourism and those where continental tourism is at the beginning of its development and without the features of mass tourism. Online questionnaires were distributed to seven managers of protected areas in October 2023. Each of the seven representatives of specific protected areas provided their responses via official email addresses on behalf of their institution. Their email addresses were collected via the official websites of the protected areas, after determining the group of areas that should be included in the study. The questionnaires were sent to one representative within one institution, or more precisely to the managers of protected areas, thus making the 100% of the returned answers with the whole population in the relevant area. The respondents were informed about the fact that their involvement in the study is voluntary and anonymous, while gathered answers will be used only for scientific purpose and in a group manner, without a possibility of their identity disclosure.

Područje istraživanja

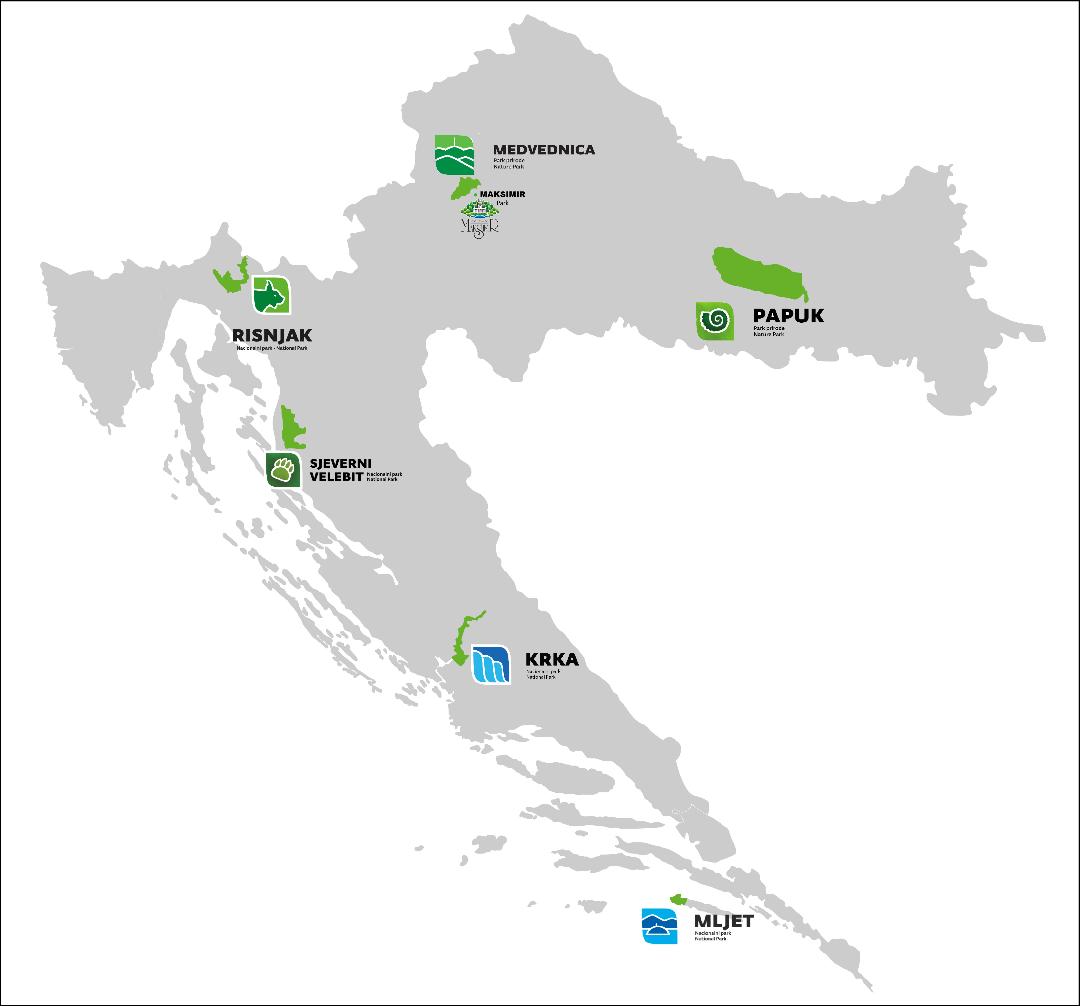

As already mentioned, the sample covered all geographic macro-regions of Croatia, to provide the possibility of comparison of the data between the regions. In the area of the Pannonian Plain the following areas were analysed: Papuk Nature Park, Medvednica Nature Park, and Maksimir Forest Park. In the mountain area Northern Velebit National Park and Risnjak National Park were analysed, while in the coastal area, Krka National Park and Mljet National Park were analysed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analysed protected areas in the Republic of Croatia

Slika 1. Istraživana zaštićena područja u Republici Hrvatskoj

Author: Dragana Markanović, Institute for Development and International Relations, IRMO, Zagreb

Mount Papuk was declared a nature park in 1999, and due to its exceptional geodiversity, it became the first Croatian geopark and a member of the UNESCO World Geoparks Network in 2007. The area of the park covers 336 km2. It mainly comprises forest areas of exceptional geological diversity, with numerous watercourses, gentle hills with vineyards at the foot of the mountain and few, but valuable grassland areas. In the area of Papuk Nature Park, significant remains of cultural heritage have been preserved – the remains of medieval cities, profane and sacral buildings and archaeological sites (Vitek, 2012). The western part of Mount Medvednica, in the northern part of the City of Zagreb, was declared a nature park in 1981, and in 2009 the park area was expanded to 17,938 ha. Complex geological processes have also affected other natural phenomena in the park. Its basic value is a complete natural forest complex that occupies 82% of the area. Tourism in the Medvednica area began to develop in the second half of the 19th century with the construction of hiking trails, mountain lodges, ski resorts, roads, cycling and educational trails (Tišma et al., 2022). Preserved heritage makes the entire area of the park an attraction that contributes to the enrichment of the tourist offer of the City of Zagreb (Popijač et al., 2022). The area of Maksimir Park in Zagreb has been a monument of park architecture since 1964 and a protected cultural and historical heritage since 1994. The area of Maksimir Park covers 356.21 ha. The park is an important element of the green infrastructure of the City of Zagreb, contributing to the well-being of people and improving the quality of life (Opačić and Dolenc, 2016). Maksimir Park has a pronounced recreational and educational function through numerous, highly attended educational programs, events and other interpretations, predominantly for domestic visitors (Marin et al., 2021).

Northern Velebit was declared a national park in 1999 due to the abundance, diversity and peculiarity of karst forms, the richness of flora and fauna and exceptional natural beauty in a relatively small area of 109 km2 (Devčić, 2021). The park is globally significant for its karst speleological objects and endemism of underground fauna, and due to these and other values, Mt. Velebit was included in the UNESCO list of biosphere reserves in 1978 (Bralić, 2005). Opening for tourism of the current area of the park started at the beginning of the 20th century when the first mountaineering shelters and the first mountaineering lodge were constructed, and the first hiking guide to Velebit was printed. Risnjak National Park was declared in 1953. Today it covers an area of 6,350 ha. The park is one of the oldest Croatian protected areas. It has extraordinary potentials of exceptional natural value – birds, large carnivores, game, vast plateaus and mountains with diverse karst phenomena (Bralić, 2005). Also, though to a lesser extent, it has intangible cultural heritage, especially traditional crafts.

Krka River flow area has been protected as a natural value since 1948, and was declared a national park in 1985, when the middle and lower course of the river was located within the boundaries of the protected area. In 1997 the border of the national park was extended to the upstream parts of the river. The basic values of the park are geomorphological and hydrological traits, accompanied by a distinctive flora and fauna (Bralić, 2005). The development of tourism in this area started from the very beginning of its protection, and it is experiencing momentum since it was declared a national park (Radeljak and Pejnović, 2008). Mljet National Park was founded in 1960. It covers an area of about 54 km2, occupying one third of the island of the same name. It received the status of the national park due to the exceptional beauty of its landscape, rich and preserved vegetation cover, valuable cultural heritage and specific features of the relief, and especially due to the specific coastal indentation (Bralić, 2005).

REZULTATI

Based on the results of the completed surveys of representatives of seven protected areas in different regions of Croatia, we have established that almost every investigated area has visitor centres, except Maksimir Park. Visitor centres are equipped with contents that correspond to the standards of well-equipped facilities of this type in protected areas in the rest of Europe (information stand, settings for the presentation of natural and cultural heritage, souvenir shops, classrooms, halls for movie projections, and some of them also have facilities for housing ecotourists). Likewise, each of the researched protected area within its boundaries has guided tours and self-guided tours. As part of such organized tours of the parks, rules of conduct or ethical codes are communicated to the visitors, which, according to the respondents, are used by all the researched protected areas. The most common ways of communicating it to the visitors are through information boards on the trails, through brochures and on the internet.

Finally, each of the protected areas develops tourism based on the adopted plans for its economic activity, and each of the interviewees believes that the interpretation of the environment contributes to the protection of nature and the preservation of natural and cultural heritage. The interviewees expressed their opinions about the ways in which it was carried out in the form of free answers, and these views were conveyed in the discussion part of the paper.

RASPRAVA

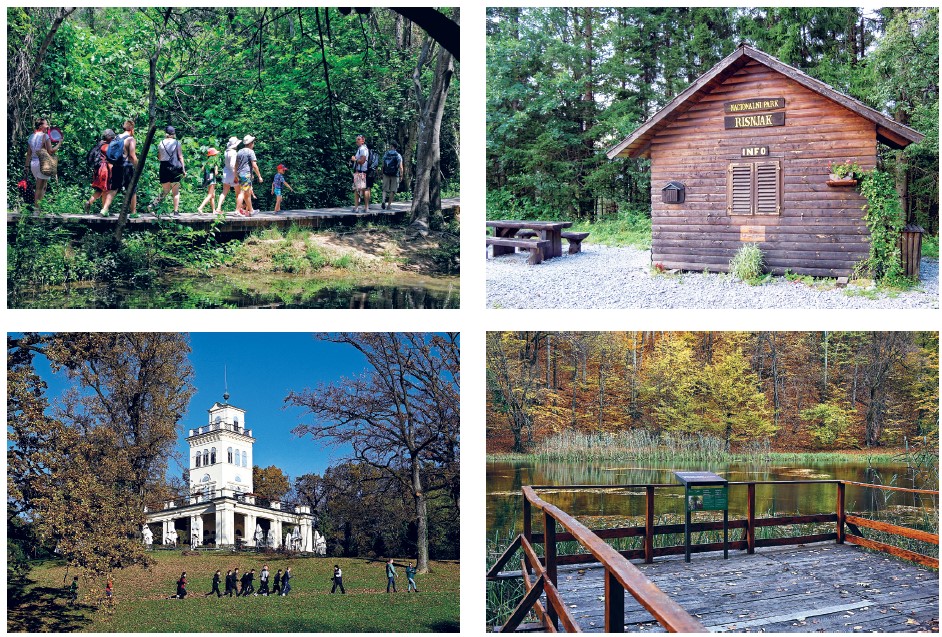

All analysed parks, regardless of the type of protection and the time of legal designation of the protected area, have a long history of recognizing and respecting the fundamental natural phenomena. In addition to the function of protection, these areas also have an increasingly significant tourist importance. The visitors’ attendance of Croatian parks has been intensified by recent investments in the development of interpretation facilities and the renovation and construction of tourist infrastructure, all of which contribute to local development (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Interpretation and dedication to visitors in protected areas of Croatia (a – visitor trail in Krka National Park; b – info-point in Risnjak National Park; c – cultural heritage as an integral part of the offer in Maksimir Park; d – platform for observing biological values in Papuk Nature Park)

Slika 2. Interpretacija i posvećenost posjetiteljima u zaštićenim područjima Hrvatske (a – staza za posjetitelje u Nacionalnom parku Krka; b – info-točka u Nacionalnom parku Risnjak; c – kulturno nasljeđe kao integralni dio ponude u Parku Maksimir; d – platforma za promatranje bioloških vrijednosti u Parku prirode Papuk)

Photo: Vladimir Stojanović

Regardless of the Croatian macro-region to which it belongs, for each researched protected area in this paper, it was reported that it is developing nature-based tourism, while ecotourism is planned and developed in Papuk Nature Park, Krka National Park, Sjeverni Velebit National Park and Medvednica Nature Park. For the needs of these forms of tourism, infrastructure with a low impact on the environment is being built (visitor centres, information boards, landscaped viewpoints), which is equally represented in the protected areas of regions with a high intensity of mass tourism (Pannonian Plain) and those regions that are not on the path of mass tourists (coastal area).

Visitor centres are facilities that provide an overall picture of the protected areas (Wearing and Neil, 2009), where modern information technologies provide tourists with information on natural values (Wearing and Schweinsberg, 2019). This is why in this research special attention was paid to those important facilities for the interpretation of protected areas. Visitor centres are gateways to protected areas from which visitors start their tour (Holloway and Humphreys, 2016). These facilities are also important because they help protect animal species through education and, generally, because they encourage tourists to get involved in protection (Newsome et al., 2005). Thus, it is encouraging that as many as six out of the seven protected areas analysed have such facilities for the interpretation of natural values and the reception of visitors (Table 2). Their contents, such as providing information, presenting natural heritage and film screening, mostly correspond to the offer of visitor centres in numerous other destinations (Eagles and McCool, 2002). In Risnjak National Park, the "Birth House of the Kupa River" was opened to visitors in the now uninhabited hamlet of Kupari. It offers visitors educational content about the natural characteristics of the river and the population inhabiting its banks. Visitor centres in Krka National Park similarly provide educational content about the Krka River. In the Velebit House, a visitor center in Northern Velebit National Park, the center of the educational story are humans and their direct and indirect impact on nature. It is common for visitor centres to expand or combine with educational centres (Wearing and Neil, 2009), and examples from Croatia clearly indicate that education is an integral part of interpretation in visitor centres of protected areas.

Visitor centres, equipped with modern methods of interpretation, with the aim of attracting a larger number of visitors, are also common in other countries of the European Union, for example in Germany, in the Bayerischer Wald National Park (Stemberk et al., 2018). Their role is crucial for encouraging visitor education and is seen as the most important factor in shaping visitor behaviour (Minciu et al., 2012). The role of visitor centres in the presentation of natural and cultural heritage is recognized in particular in geodiversity, biodiversity and cultural diversity (UNESCO, 2023), and such a concept, through the design of naturalist settings, is also common in the following European countries: Iceland (Burns et al., 2021), Northern Ireland (Great Britain), Lithuania, Romania (Jarolímková and Elss, 2023), but also in other parts of the continent. According to this research based on the surveys completed by the respondents, it can be observed that the presentation of natural and cultural heritage, together with the presentation of films, which are an important means of education, represent the dominant content of interpretation in the researched visitor centres. This type of heritage presentation is desirable, encouraging and should ensure an increase in the number of visitors in the future.

Table 2. Facilities in visitor centres in protected areas of the Republic of Croatia

Tablica 2. Sadržaji u centrima za posjetitelje u zaštićenim područjima Republike Hrvatske

Source: Authors

The role of humans in nature should be an indispensable part of the presentation of the values of protected areas (Ham, 1992). The promotion of cultural heritage in visitor centres, but also on educational trails, is strongly present in Croatian protected areas. In Papuk Nature Park, the "Count's educational trail in Jankovac" was named out of respect for Count Josip Janković, responsible for arranging of the site situated in the area of today's park. In Medvednica Nature Park, the Zrinski mine from the 16th century is available to visitors, while on the routes of Mljet National Park there are numerous archaeological sites, churches and monasteries. This way of presenting and interpreting cultural content emphasizes the connection of nature, people and their history, while the interpretation of prehistoric and historic monuments is of particular importance (Tilden, 1957). Otherwise, there is a danger that protected areas could be presented to visitors as dehumanized and deprived of the human element (Wearing and Schweinsberg, 2019). The analysis shows that this phenomenon has been avoided in protected areas throughout Croatia.

Most of the representatives of protected area managers in this research stated that interpretation on the spot and with the help of guides is the best way to present the value of these protected areas. Oral presentation of natural values is one of the basic forms of interpretation in guided tours. Oral presentations with a guide are linear, because they take place in a definite sequence which is defined by the guide (Ham, 1992), as well as by the protected area manager who defines the route programs. For example, the programs of such routes are precisely defined in Northern Velebit National Park according to the locations of visits and hourly rates, while the same is the case in Mljet National Park, where five routes are accurately predetermined, which are the examples of linear principles in interpretation. Furthermore, other protected area managers have expressed the importance of oral and guided routes: "the interpretation of the 'living word' – in situ – should be retained and used as much as possible, because in this way the visitor can feel the environment, climate, circumstances in which this natural value survives" [Krka National Park, source based on the survey responses]. The importance of education in childhood is emphasized in particular in such oral and educational routes, because such interpretation intended for children must not be a dilution of content intended for adults, but must be prepared in such a way so that it provides its essence (Tilden, 1957). Programs intended for children exist, for example, in Risnjak National Park, with a linear program elaborated in detail.

Self-guided tours are desirable and favourite among visitors, as they allow freedom in the pace of movement and mastering a particular trail, and studies have shown that independent tourists show greater affection for this way of getting to know the protected area (Wearing and Neil, 2009). For this reason, they are welcome in areas where there is no mass tourism, as it is the case in Papuk Nature Park. However, such tours are also present in all other analysed protected areas of Croatia, as proved by the large number of information and interpretation boards on educational trails. Signs and platforms are very important for this type of interpretation, because where there are none, visitors who prefer self-guided tours might be frustrated (Fennell, 2015). Numerous projects financed through the EU funds with the aim of improving the interpretation of natural values and eliminating deficiencies have helped Croatia improve the interpretation of visits relying on self-guided tours (Kreitmeyer, 2018). That is why each of the seven analysed protected areas also offers self-guided tours.

Guided tours and self-guided tours are organized in other protected areas of Europe according to a similar model, which has also been observed in Croatia. In the Central Bohemian Uplands Protected Landscape Area, in the Czech Republic, such tours are organized as educational events of importance for raising environmental awareness (Ralle, 2019). In Fulufjället National Park in Sweden, guided tours, according to the survey of visitors, help to better understand the natural values of that national park, while the importance of guided tours in Finland is also indicated by the fact that an increasing number of visitors are ready to pay for such services to tourism companies (NCM, 2019).

Well-performed communication, for example between managers and visitors, can build public support for the preservation and management of protected areas. Clear and customized messages are essential when addressing visitors through brochures, newsletters, or websites (Leung et al., 2018). In protected areas, the interpretation must focus on education, especially related to the heritage of the site (Spenceley et al., 2015). The representatives of the managers of the researched protected areas of Croatia understand this importance, which is clear in their statement emphasizing the following attitudes: "(it is important to) educate visitors regarding protected areas in the need for protection, so that everyone could be as responsible as possible for the areas they visit, because tourism is the leading challenge of every destination, especially of protected areas" [Krka National Park].

Being an important tool in visitor management (UNEP & WTO, 2005), codes of ethics encourage environmentally, socially and culturally appropriate and acceptable behaviour of visitors (Fennell, 2015). Codes of ethics are evidence of the mutual links between ethics and natural environment, in the process of using natural resources through tourism (Payne and Dimanche, 1996). The importance of codes of ethics is well recognized in the examined protected areas, since each of the managers uses them in the personal practice of tourism development in those protected areas. Thus, Papuk Nature Park warns visitors not to damage the vegetation, not to hunt and not to kill animals; likewise, Northern Velebit National Park warns them not to harvest plants and mushrooms; Krka National Park warns them not to harvest plants and not to disturb game, including the disturbance caused by drones. These rules clearly highlight the importance of the environmental code (Fennell, 2015; Holden, 2008), and such practice is known in many other destinations around the world, for example in Canada (Edgell, 2020), which has a long tradition of applying the principles of sustainability in tourism in protected areas. There are various ways of communicating codes of ethics worldwide (Stojanović, 2023). In the researched protected areas of Croatia the communication of codes of ethics is most often performed through information boards as well as along educational paths, through brochures and internet portals (Table 3).

Table 3. Codes of ethics and how they are communicated to visitors in protected areas

Tablica 3. Etički kodeksi i kako se oni prenose posjetiteljima zaštićenih područja

Source: Authors

Codes of ethics should be linked to the environmentally responsible or irresponsible behaviour of visitors in the researched protected areas. Periodic reports on nature protection show that illegal activities by visitors are sporadic and almost unrecorded in Risnjak, Sjeverni Velebit and Mljet national parks (https://www.np-risnjak.hr/en/, https://np-sjeverni-velebit.hr/www/en/), https://np-mljet.hr/?lang=en), while Krka National Park recorded a slightly higher number of incidents, where the destruction of strictly protected plant and animal species was also recorded (https://www.npkrka.hr/en_US/). Medvednica Nature Park is near a densely populated area, so there has been a large number of destructions of visitor infrastructure such as boards and signs (https://www.pp-medvednica.hr/en/), while in Papuk Nature Park there is also a problem with camping in places that are not intended for that purpose (https://www.pp-papuk.hr/?lang=en).

The results of our research have shown that each representative of the protected area managers was explicit in their view that a good interpretation contributes to the protection of natural and cultural heritage. Their explanations include the following views based on their experience: "(interpretation) causes less vandalism and degradation" [Northern Velebit National Park], "quality interpretation allows not only visitors, but also the local community to learn about the values of heritage, and thus to understand that the need for protection extends beyond the protected area, which directly or indirectly affects the protected area" [Krka National Park], "quality interpretation introduces the topic of nature protection to visitors, which is not clear enough to most visitors" [Papuk Nature Park]. Based on the views on the necessity of interpretation, the representatives of the managers also made proposals for improving the interpretation tool: "it is necessary to have more employees in charge of interpretation" [Northern Velebit National Park], "develop a network of local guides, since in order to ensure quality it is not enough just to display educational boards" [Papuk Nature Park], "use interdisciplinary approach and intensify the promotion of the existing infrastructure" [Maksimir Park].

ZAKLJUČAK I BUDUĆA ISTRAŽIVANJA

Environmental interpretation in protected areas stands out as very important, because it provides visitors with relevant information and content for a better quality of their stay in nature. Furthermore, based on the interpretation, a higher level of nature protection should be encouraged, while the number of incident situations by visitors with a negative outcome for natural values should be reduced. Numerous and varied professional literature supports the importance of topics on ecological interpretation.

This research was conducted in seven protected areas of Croatia and in its different geographical regions, with the aim of getting a better idea of the interpretation of heritage as a very important tool in visitor management and nature protection. All researched protected areas are well versed in the importance of interpreting natural values for visitor management and nature protection, as proved by the wide range of tools they apply for this purpose. Most applied tools are as follows: interpretation in visitation centres; guided tours; self-guided tours; publications, brochures and codes of ethics. The causes of this trend in the development of sustainable tourism of Croatian protected areas should lie in projects that have helped in enhancing interpretation. Thus, for example, in the period from 2014 to 2020 alone, about twenty projects funded by the European Union were implemented.

The results of our research show that visitor centres have one of the leading roles in the interpretation of the environment of protected areas due to the variety of contents offered, which range from providing information to providing accommodation services. According to the managers of the researched protected areas in this paper, interpretation on the spot with the help of a guide is the best way to present the value of these protected areas. Since the stay of visitors in nature also represents a potential danger to nature, each of the managers is aware of the role of ethical codes in the interpretation and management of visitors. However, the shortcoming of this research is that it cannot highlight sufficiently clear the evidence that would point to the effectiveness of the application of ethical codes, since there is still no way to quantitatively separate incidents of vandalism committed by tourists from those committed by other visitors to protected areas.

In future research, based on the statements of the representatives of the protected area managers on monitoring the satisfaction of visitors which they conduct, quantitative research on the effectiveness of interpretation in the conservation and protection of nature should be realized. Besides that, an analytical approach for connecting the obtained results with the effects of the function of education and interpretation on the level of preservation of an individual protected area might be further conducted. In such research, reports from the nature conservation service on the illegal behaviour of visitors, degradations caused by visitors, violations and imposed sanction might be consulted. Altogether, they could provide an overall review and concrete results, with the aim of their implementation in plans and strategies for the development of protected areas in Croatia.