INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of gastrointestinal disorders with the principal phenotypes of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) (1, 2). The prevalence of IBD is estimated to be 1.5 million and 2 million cases, resp., in North America and Europe (3). The underlying mechanisms of IBD are complex, involving the interplay of genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and alterations in the intestinal microbiome, which impair intestinal barrier function and disrupt immune responses (4). Evidence has shown significant inflammatory cell infiltration in the intestinal mucosa of IBD patients (4). The activation of white blood cells in the mucosa is a key process in IBD pathogenesis, mediated by selectins, integrins, chemokine receptors, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and mucosal addressing cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) (5). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine, plays a role in IBD pathogenesis (6). TNF-α inhibitors were the first class of biological agents approved for IBD treatment, effective against both luminal and extraintestinal manifestations (7). However, these inhibitors can increase susceptibility to serious infections and may lead to treatment failures, resulting in reduced drug efficacy (8, 9).

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds alpha4beta7 (α4β7) integrin to suppress the adhesion and migration of lymphocytes, and this disruption can decrease the inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract (10). Vedolizumab has been reported to be indicated for UC or CD patients at moderate to severe activity with an inadequate response to TNF-α inhibitors (10). Guidelines suggested that the selection of first-line biological agents for IBD patients should be based on efficacy, safety, cost, clinical factors, patient preference, and likely adherence (11). Some studies reported controversial results on the efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors and vedolizumab for treating IBD patients (12, 13). Hahn et al. (9) revealed no significant difference in remission rates between vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors in IBD patients, whereas Sablich et al. (10) reported the superiority of vedolizumab to TNF-α inhibitors in clinical remission (CR) for IBD patients. In addition, Moens et al. (11) found inconsistent results on the forms of IBD that vedolizumab was superior to TNF-α inhibitor regarding endoscopic remission and treatment persistence in UC, while no difference was found in endoscopic remission and treatment persistence in CD.

Considering that there is limited evidence regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of TNF-α inhibitors and vedolizumab in IBD, systematic reviews and meta-analyses synthesizing data pertaining to biological agents (vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors) were needed. A meta-analysis compared vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors for the treatment of IBD patients, although it did not include a direct head-to-head comparison (7). Another meta-analysis focused on comparing vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors specifically for treating patients with UC, without considering those with CD (5). Therefore, the current meta-analysis is performed in a head-to-head manner to comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors in patients with IBD. Further, the efficacy and safety of these biological agents were assessed in individuals with different forms of IBD.

SOURCES AND METHODS

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (14).

Literature search strategy

Two researchers independently performed systematic searches of Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library up to November 15, 2024, for relevant studies. The search strategies are shown in Supplementary File 1. The third researcher provided the consultation if conflicts existed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (i) patients – IBD patients (CD, UC, or IBD-unclassified), (ii) intervention – vedolizumab group, (iii) control – TNF-α inhibitors group (including etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, or golimumab), (iv) outcomes – clinical remission, clinical response, steroid-free remission (SFR), endoscopic remission (ER), histologic remission (HR), endoscopic improvement (EI), treatment failure (TF; IBD-related surgery or hospitalization), adverse events (AEs, severe AEs, infections, or severe infections), (v) studies – cohort studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Exclusion criteria: (i) animal studies or in vitro experiments, (ii) conference abstract, case report, meta-analysis, review, editorial materials, letters, guidelines, news items, patents, (iii) not published in the English language, (iv) articles that have been withdrawn, (v) topic failing to meet the requirements. Details of the definition of outcomes are attached in Supplementary File 2.

Data extraction

Two researchers independently performed the data extraction. The following characteristics were extracted from the studies: the first author, country, publication year, study design, biological treatment, IBD subtype, sample size, sex, age, follow-up time, diagnosis age, disease duration, Mayo score, and prior biologic therapy.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) was employed to assess cohort studies, with evaluation conducted across three dimensions (selection of study population, comparability of the groups, and outcome evaluation) (15). The studies included in the analysis were categorized based on their quality, with low-quality studies receiving scores of 1 to 3 points, moderate-quality studies scoring between 4 and 6 points, and high-quality studies achieving scores of 7 to 9 points. Higher scores represented a higher quality of studies.

The RCTs included in the meta-analysis were assessed using the Jadad scale, which was evaluated in four dimensions (generation of random sequence, randomization concealment, blinding, withdrawal, and loss of follow-up) (16, 17). Based on the Jadad scale scores, studies were categorized into low quality (1–3 points) and high quality (4–7 points), with higher scores indicating more rigorous and reliable study designs.

A pooled relative risk (RR) with a 95 % confidence interval (CI) was calculated for counting data. A heterogeneity test was conducted to assess the statistical heterogeneity across the included studies by using the I2 statistic. The random-effects model was employed to perform meta-analyses if I2 ≥ 50 %, and the fixed-effects model was used if I2 < 50 %. A subgroup analysis was conducted to elucidate the source of heterogeneity, based on IBD subtypes. The presence of bias in the published literature was evaluated for the outcomes using Begg’s test (18). A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the reliability of the pooled results by sequentially removing the individual study. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata15.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), and a p-value of less than 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Search results and study characteristics

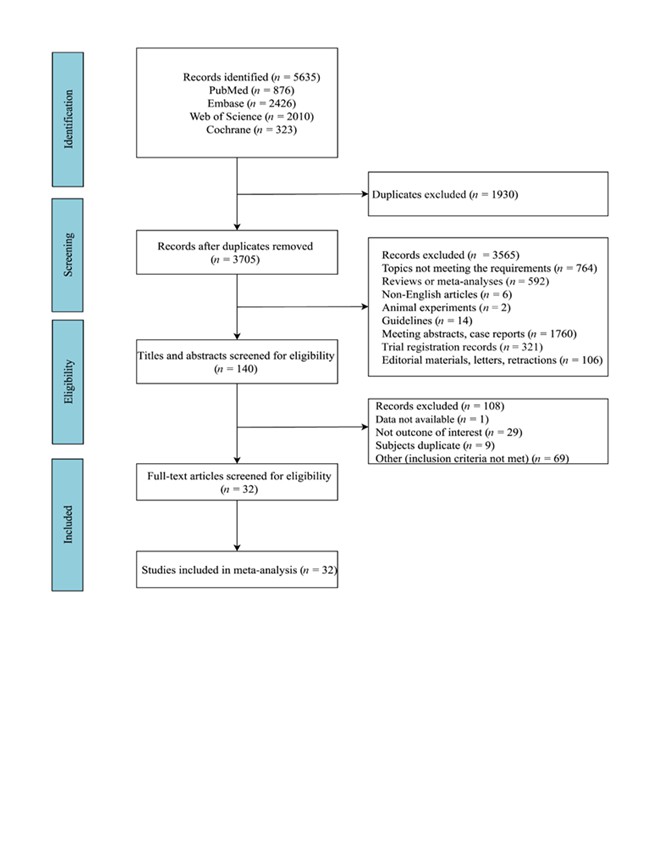

Finally, 5,635 articles were included, of which, 1,930 duplicates were removed. Following an initial screening, 3,565 articles were excluded for the following reasons: topics not meeting the requirements (n = 764), reviews or meta-analyses (n = 592), not published in English (n = 6), animal experiments (n = 2), guidelines (n = 14), meeting abstracts, or case reports (n = 1,760), trial registrations records (n = 321), editorial materials, letters or retractions (n = 106). After screening the full text, 108 articles were excluded: data not available (n = 1), outcome not meeting the requirements (n = 29), duplicated subjects (n = 9), or other excluded criteria (n = 69). Finally, 32 eligible studies were included (Fig. 1) (12, 13, 19–48).

Fig. 1. The flowchart of the study search.

Table I shows the included studies’ characteristics. There were 31 cohort studies and 1 randomized controlled trial involving 5,640 patients in the vedolizumab group and 15,480 patients in the TNF-α inhibitors group. According to the NOS scores, 19 studies met 7–9 criteria (NOS, high quality) while the remaining 12 studies met 6 criteria (NOS, moderate quality). One RCT study obtained 6 points by Jadad scale scores and was assessed as high quality.

Table I. The characteristics of the included studies

AEs – adverse events, EI – endoscopic improvement, CD – Crohn’s disease, CR – clinical remission, ER – endoscopic remission, HR – histologic remission, RCT – randomized controlled trial, SFR – steroid-free remission, TF – treatment failure, TNF – tumor necrosis factor, UC – ulcerative colitis

* – mean (SD), ** – median (IQR), ^ – median (Q1, Q3)

Pooled results for the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors

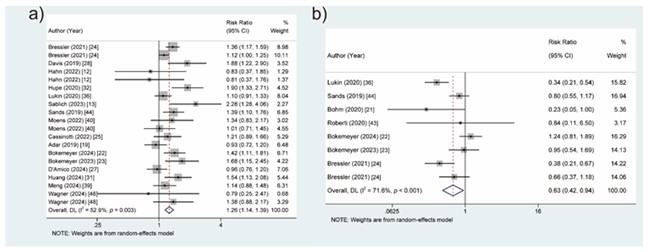

Compared to TNF-α inhibitors, vedolizumab was superior in clinical remission (RR = 1.26, 95 % CI: 1.15–1.39) (Fig. 2a) for IBD patients. In terms of safety, the pooled results showed that the risk of severe AEs (RR = 0.63, 95 % CI: 0.42–0.94) (Fig. 2b) in the vedolizumab group was lower than in the TNF-α inhibitors group. No significant differences were observed in clinical response, ER, SFR, HR, EI, IBD-related hospitalization, AEs, infection, and severe infection between the vedolizumab group and TNF-α inhibitors group (Table II).

Fig. 2. Forest plots of vedolizumab vs. TNF-α inhibitors for the efficacy and safety of treating patients with IBD: a) clinical remission, b) severe AEs.

AEs – adverse events, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, TNF – tumor necrosis factor

Table II. Pooled results for efficacy and safety of vedolizumab vs. TNF-α inhibitors in IBD patients

AEs – adverse events, CI – confidence interval, EI – endoscopic improvement, ER – endoscopic remission, HR – histologic remission, I2 – I-squared statistic, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, RR – relative risk, SFR – steroid-free remission, TF – treatment failure, TNF – tumour necrosis factor

Subgroup assessment

Table III summarizes the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors according to different types of IBD. We also found the superior efficacy of vedolizumab to TNF-α inhibitors in clinical remission (RR = 1.38, 95 % CI: 1.24–1.55), clinical response (RR = 1.19, 95 % CI: 1.05–1.34), SFR (RR = 1.21, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.43) for UC patients. A superior clinical remission (RR = 1.16, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.31) of vedolizumab (vs. TNF-α inhibitors) was also observed in CD patients. Compared to the TNF-α inhibitors, vedolizumab was associated with decreased AEs (RR = 0.70, 95 % CI: 0.54–0.92) and severe AEs (RR = 0.56, 95 % CI: 0.34–0.93) in UC patients.

Table III. Pooled results for efficacy and safety of vedolizumab vs. TNF-α inhibitors in IBD subtypes

AEs – adverse events, EI – endoscopic improvement, CI – confidence interval, ER – endoscopic remission, HR – histologic remission, I2 – I-squared statistic, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, RR – relative risk, SFR – steroid-free remission, TF – treatment failure, TNF – tumor necrosis factor, UC – ulcerative colitis

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the estimates did not significantly vary when omitting studies one by one (Table II). Publication bias was deemed not to be significant for clinical remission (Z = 1.01, p = 0.327), clinical response (Z = 0.82, p = 0.429), SFR (Z = 1.28, p = 0.219), and AEs (Z = –1.72, p = 0.111) (Table IV).

Table IV. Publication bias of outcomes by Begg’s test

| Outcomes | Begg’s test | |

|---|---|---|

| Z | p | |

| Clinical remission | 1.01 | 0.327 |

| Clinical response | 0.82 | 0.429 |

| SFR | 1.28 | 0.219 |

| AEs | –1.72 | 0.111 |

AEs – adverse events, SFR – steroid-free remission

In the current meta-analysis with 32 studies, vedolizumab yielded better efficacy (clinical remission) and safety (severe AEs) than TNF-α inhibitors in IBD patients. Especially in UC patients, vedolizumab may achieve better performance in clinical remission, clinical response, SFR, AEs, and severe AEs.

Implications of the outcomes

TNF-α inhibitors are widely used biological agents in the clinical treatment of IBD and can be capable of neutralizing TNF-α (6). A meta-analysis suggested that TNF⁃α inhibitors monotherapy or combined therapy was the preferred strategy for mucosal healing in IBD compared to conventional treatments such as glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, and salicylic acid formulations (49). Vedolizumab was a selective treatment of IBD by blocking white blood cell transport to the intestines (50). TNF-α inhibitors and vedolizumab can both effectively induce and maintain mucosal healing, and have become the first-line biological agents for the treatment of IBD (12). A previous meta-analysis that included 14 studies on IBD demonstrated similar results in the efficacy and safety profiles of infliximab and vedolizumab by comparing the occurrence rates of various outcome measures (7). A study by Cholapranee et al. (51) reports that both anti-TNF and anti-integrin biologics (vedolizumab) effectively induced mucosal healing in UC patients compared to placebo. A network meta-analysis ranked infliximab and vedolizumab highest among first-line treatments for inducing remission and mucosal healing in moderate-to-severe UC, based on indirect comparisons (52). Additionally, a head-to-head randomized trial demonstrated that vedolizumab was more effective than adalimumab in achieving clinical response and remission during both induction and maintenance therapy, while also providing a favorable balance of efficacy and safety compared to other available UC treatments (53). Consistently, our meta-analysis showed that vedolizumab exerted a better effect on clinical remission than TNF⁃α inhibitors in IBD patients.

Some IBD patients may demonstrate a lack of response or a reduction in response to TNF-α inhibitors, which are also linked to higher risks of infections and malignancies (54). Different from TNF-α inhibitors, vedolizumab inhibits the interaction between white blood cells and the intestinal vascular system by blocking the binding of integrin and MAdCAM-1 on intestinal endothelial cells to accurately and selectively suppress intestinal inflammation without any adverse effects of systemic immune suppression (5). Our results indicated that the risk of severe AEs of vedolizumab was lower than that of TNF-α inhibitors in IBD patients. This may be explained by the intestinal selective effect of vedolizumab, which did not affect the body’s immune function, thereby increasing safety. Further, we found that the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab were superior to TNF-α inhibitors regarding clinical response, SFR, AEs, and severe AEs in patients with UC while not in patients with CD. This finding indicated that vedolizumab may be more suitable for UC patients, and the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab needed to be further explored in CD patients.

While discussing, we highlight that although vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors have shown positive efficacy in many patients with IBD, a subset of patients are insensitive to or do not respond well to these treatments. Therefore, the exploration of novel therapeutic approaches is critical for these nonresponsive patients. In recent years, Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitors such as tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, etc. (55), and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulators, such as etrasimod (56), have shown promising clinical effects, providing new options for patients with refractory IBD. In addition, biological agents targeting IL-23/12, such as ustekinumab and mirikizumab (57), are also in clinical use, and these agents target different inflammatory pathways through different mechanisms, which may open up new therapeutic prospects for patients who have failed to benefit from traditional therapies. Therefore, future studies need to focus on the long-term efficacy and safety of these new therapies in order to provide a more comprehensive treatment strategy for IBD patients.

Limitations of the study

However, it should be noted that this meta-analysis is not without limitations. First, only studies published in the English language were included, and it may lead to a bias related to language. Secondly, while our subgroup analyses were performed based on different subtypes of IBD, we observed that some outcomes still exhibited heterogeneity. Additionally, prior biologic therapy and variations in treatment protocols may influence the assessment of both efficacy and safety of the treatments. However, due to limitations in the original studies, we are unable to conduct further analyses to explore these factors in more depth. Third, the included studies are all performed in Europe and America. It is not possible to generalize the findings to patients living in other areas. In the future, more RCTs need to be performed to further explore this in patients from the other areas.

CONCLUSIONS

We explored the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and TNF-α inhibitors in patients with IBD based on currently available studies. The present meta-analysis provided evidence that vedolizumab could be a preferred treatment option that combines both efficacy and safety for patients with IBD, particularly in those with UC. These results highlight the potential of vedolizumab as a targeted therapy that may reduce the systemic side effects associated with traditional TNF-α inhibitors. Our findings provide direct evidence for the use of vedolizumab in the treatment of IBD. Future large RCTs with robust designs and multicenter involvement are essential to further validate these findings and explore optimal treatment protocols.

Acronyms, abbreviations, codes. – AEs – adverse events, α4β7 – alpha4beta7, CD – Crohn’s disease, EI – endoscopic improvement, ER – endoscopic remission, HR – histologic remission, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, MAdCAM-1 – mucosal addressing cell adhesion molecule-1, NOS – Newcastle-Ottawa scale, RCTs – randomized controlled trials, RR – relative risk, S1P – sphingosine 1-phosphate, SFR – steroid-free remission, TF – treatment failure, TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor-α, UC – ulcerative colitis, VCAM-1 – vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Supplementary materials are available upon request.

Conflict of interests. – The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding. – No funding was received.

Authors contributions. – Conceptualization and design, Y.L., J.D. and Q.W.; collecting the data, Y.L., C.L. and Y.H.; analysis and interpretation, Y.L., C.L. and Y.H.; writing, original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing, review, and editing, J.D. and Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.