INTRODUCTION

Resilience is a multifaceted and multidisciplinary concept that attracts a great deal of research across numerous and diverse academic disciplines - from ecology, engineering and computer sciences[1-4], across psychology, medical sciences and social work[5, 6], to marketing, management and accounting[7-9]. Consequently, there is no straightforward definition of resilience.

At an individual level, resilience is conceptualized as the capability of individuals to recover from adversities or as the process of adaptation to adversity[10-12]. Sparse studies of consumer resilience conceptualize resilience at an individual level and explore how consumers recover or adjust their consumption habits after experiencing some form of adversity situation. However, the concept of adaptive responses is not developed in these studies, while antecedents and consumer behavior consequences remain under-explored. This is particularly valid in the online context which is gaining importance with increasing digitization of the entire value chain.

Other key aspect of this research – online privacy – involves the rights of an individual concerning the storing, (re)using or provision of personal information to third parties and displaying of information pertaining to oneself on the Internet. In the digital era, the online privacy concept focuses on personal information shared with family, friends, businesses, and strangers, while at the same time engaging in self-protection of sensitive information[13]. Modern lifestyle increased demand for information and the spread of new technologies that gather personal information that limit the purely private spaces and increase the number of privacy violation cases in terms of unauthorized collection, disclosure, or other use of personal information.

This research connects these two concepts – resilience and online privacy violation. Nowadays, resilience attracts increasing research interest in the new domains, such as the context of information security, digitalization of trade and services, and extent of Internet usage. On the other hand, understanding privacy issues related to resilience and their effect on consumer behavior, specifically in an online environment, is limited and studies on consumer resilience to online privacy violation are missing. This subject is worth exploring, since individuals who experienced online privacy violations might change their subsequent online behavior and intentions to adopt new online services and/or technologies. If the trust after online privacy violation is not restored or if new online activity equilibrium is established at the lower level of consumer activity, the implications might be disturbing for business and public policies. Although research on privacy and resilience certainly has its applicative value in everyday life, the phenomenon of resilience to privacy violations remains largely under-explored.

This literature review paper has threefold aim: (i) it aims to provide a contemporary literature review of resilience related concepts, with special emphasis on resilience concepts used in social research environment focusing on individual consumer and their behavior; (ii) it also provides a contemporary literature review of privacy related concepts, with special focus on privacy and privacy violation in an online environment; and (iii) this research aims to set grounds and offer suggestions for future development of both conceptual and empirical research frameworks to assess consumer resilience to online privacy violation. We employed a non-systematic literature review of resilience and privacy concepts and definitions across various academic disciplines which may be adapted for the specific purpose of researching consumer resilience to privacy violation in an online environment and to define future research directions

Our work adds to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, as already stated above, evolving economic and technological advances are constantly increasing the rate of digitalization of entire value chain, which in turn increases the need for large amount of (individual) information to be available online, and raises the opportunity of online privacy violation. Therefore, growing attention of both academic and professional community is given to individual resilience to these adverse privacy intrusion events. Furthermore, online privacy has recently gained importance, especially since the introduction of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Governments and businesses are shaping their strategies to be in line with these regulations and to improve security for their online purchases. Thirdly, since both concepts of “resilience” and “privacy” have originated outside of social domain and outside of online environment, this research presents an important novelty since these two concepts are adapted to suit the consumer-based analysis in digital society. Finally, as resilience to online privacy violations may become more important given the current level of digitalization, this research provides an avenue for future research on both conceptual and empirical research frameworks on this topic.

This paper starts with a brief description of methodology used for literature review. The third section introduces the concept of resilience across various disciplines, and presents context and issues related to consumers’ resilience. The fourth section elaborates an individual approach to researching consumer behavior related to privacy violation in an online environment, followed by the section which combines concepts presented in previous two sections i.e. it connects resilience with online privacy violation concerns. The sixth section identifies key issues for future research and offers suggestions on how to develop a research model of consumer resilience to online privacy violation, and the last section concludes.

METHODOLOGY

As the main purpose of this paper is to develop a future research framework for assessing consumer resilience to online privacy violation, we conducted a non-systematic literature review[14,15], also called a narrative style literature review[16]. The main goal of this method is to identify a gap in the literature, to summarize relevant published research studies, and to define future research directions that have not been previously addressed[16]. This literature review type is considered vital for articles “devoted specifically to reviewing the literature on a particular topic”[17; p. 311], as well as “a valuable theory-building technique”[17; p. 312]. Since the present study aims to contribute to the existing theory by analysing and describing theoretical and empirical findings of previous research studies, and thus creating a conceptual model as a future framework for assessing consumer resilience in an online setting, the applied narrative literature review approach can be considered valid.

This article represents an overview article (also known as a narrative overview or an unsystematic narrative review; according to Green et al.[18] and it is one of the three possible types of narrative reviews of the literature (for other types see Green et al.[18]). To assure the objectivity of the narrative literature review approach, as well as the structural consistency with the previous overview articles, the authors of this article followed one of the widely adopted standard patterns of a narrative literature review explained by Green et al.[18]. After the article title and structured abstract were given, the main components of a narrative overview included in the article are Introduction, Methods, Discussion, and Conclusion, following by Acknowledgement and References section. The very similar IMRaD approach – Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion[16,19] – has not been applied, since the Results section of the article is missing in this study as it is not empirical but conceptual in its nature.

For the present study, literature searches were conducted within the Google Scholar database using relevant keywords related to resilience, its antecedents, and its outcomes. The following keywords were used as starting search terms: “resilience”, “antecedents of resilience”, “outcomes of resilience”, and “consequences of resilience”. Upon authors’ decision, the inclusion criteria referred to the academic articles from various scientific areas, since resilience is a multidisciplinary concept. The exclusion criteria were also established by authors, and they referred to articles not available through the full-text option and not written in English. The authors made a conscious, joint, and iterative decision to consider each found article as relevant and to include them in this review.

THE CONCEPT OF RESILIENCE

This chapter starts by briefly elaborating different views on resilience concept across various academic disciplines. It then focuses on explaining key concepts related to resilience of systems and individuals.

RESILIENCE AS A HOLISTIC CONCEPT

Resilience can be defined as a broad application of failure-sensitive strategies that reduce the potential for and consequences from erroneous actions, surprising events, unanticipated variability, and complicating factors[20]. Many argue, however, that resilience has become a “boundary object” across disciplines which share the same vocabulary, but with different understanding of the precise meaning. Brand and Jax[1; p. 9]note that resilience as a boundary object is “open to interpretation and valuable for various scientific disciplines or social groups, (…), and can be highly useful as a communication tool in order to bridge scientific disciplines and the gap between science and policy”. Most of related literature develops resilience as a theoretical concept in their relevant fields, but empirical research (case studies, surveys, or modelling) which would test these theoretical approaches are rather rare.

The term resilience originates from the Latin word resilire, meaning to spring back. It was first used in physics and technical sciences to describe the stability of materials and their resistance to external shocks. In his seminal work, Holling[21] defined engineering resilience as the ability of a system to return to an equilibrium or steady-state after a disturbance, measuring how long it takes for a system to bounce back after a shock.

Hollings’[21] concept of resilience refers to the robustness or resistance on the one hand, versus adaptive capacity on the other, i.e. from these two approaches it is not clear if a resilient system resists adverse conditions in the first place or adapts to them after they have occurred[22] and in what time span it occurs. Longstaff, Koslowskib and Geoghegan[23] in their attempt to systemize holistic resilience concepts across various disciplines describe four types of resilience:

a) Resilience defined as the capacity to rebound and recover is predominantly adopted in traditionally engineered and other designed systems where resilience is seen as a system property or measure of stability.

b) Resilience defined as the capability to maintain a desirable state or to bounce back to an approved equilibrium or assumed normal state is predominantly employed in business, psychology, and other social sciences disciplines.

c) Resilience defined as the capacity of the systems to withstand stress where high resilience implies sufficient robustness and buffering capacity against a regime shift and/or the ability of system components to self-organize and adapt in the face of fluctuations.

d) Resilience defined as the capability to adapt and thrive is often conceptualized in social systems and psychology as a skill that an individual or group can use when facing disturbance that will allow them to reach a level of functionality which has been determined to be “good”. These disciplines acknowledge the existence of multiple possible states after the disturbance event, ranging from a worse-than-before, acceptable level to an even better post-disturbance state.

While resilience has a clear definition within engineering and psychology, this is not the case within the social complex adaptive systems research domain. Masten and Obradovic[24] pointed out that resilience theory across the developmental and ecological sciences was rather similar and that findings from the developmental theory and social resilience research were instructive for both individual and community resilience. Adaptive systems are crucial for the resilience of people, including their intelligence, behavior regulation systems, and social interactions with family, peers, school, and community systems. These adaptive systems for human resilience include regulatory systems, personal intelligence, and motivation to adapt, macrosystems (such as governments, the media), as well as knowledge, memories, and experience of individuals, families, and communities. A process of adaptation after a disturbance or adversity is influenced by economic development, social capital, information and communication, competences, and trusted sources of information[25].

There are two different approaches to the concept of resilience. The first approach deals with the resilience at the systemic level. This approach analyses resilient systems, their characteristics, and responses. In general, resilient systems are able to restore their functions after disturbance. The second approach refers to the resilience at the level of individuals. Resilient individuals have the capacity to adapt positively to stressful events. Studies within this approach are mainly focused on the characteristics of resilient individuals and the processes of attaining resilience.

KEY RESILIENCE CONCEPTS

The concept of resilience in systems is mostly developed in the context of ecological and environmental systems. The focus on system properties that emphasizes constant change and reorganization has been a great strength of this concept of resilience. Resilience thinking is very valuable in framing and discussing aspects of sustainability and sustainable development. Furthermore, this concept of resilience is highly flexible and can be applied to a range of systems across a range of scales from individuals to households, communities, regions, and nations.

Resilience thinking represents a conceptual vagueness of the definition of resilience and reveals blurred boundaries among concepts used in the research of resilience. Resilience thinking deals with the dynamics and development of complex social–ecological systems, addressing three central aspects: resilience itself, adaptability, and transformability[26]. To better understand the application of resilience concepts, the main terms used in the resilience thinking (resilience, adaptive capacity, adaptability, transformability, adaptation, vulnerability and robustness) will be explained according to Martin-Breen and Anderies[27].

Resilience in complex adaptive systems is best defined as the ability to withstand, recover from, and reorganize in response to crises. It is the appropriate framework to be applied to conditions prevailing in dynamic systems that undergo permanent internal changes. In such systems there is no fixed normal state, only functions of the systems are fixed and known. Therefore, after the disturbance, a resilient system will have its functions restored, yet not at the same level or in the same way as it was before the disturbance. Application in the literature is mostly in ecology and developmental psychology, specifically in child development.

Adaptive capacity is closely related to resilience. According to Dalziell and McManus[28], adaptive capacity is a mechanism for resilience since it reflects the ability of the system to respond to external changes, and to recover from damage. System characteristics that enhance resilience are diversity, efficiency, adaptability, and cohesion[29], but it remains unclear how to connect these system characteristics with the characteristics of an individual. Adaptive capacity and transformability are two aspects of resilience. Adaptive capacity refers to the capability of a particular system to effectively cope with shocks. Increased adaptive capacity would facilitate adaptation to changes, thus increasing resilience.

Adaptability is the key feature of complex adaptive systems which, if resilient, maintain their functions after the disturbance, but, due to the adaptability, not in the same structure as before the crisis. Complex adaptive systems may also assume new functions, so transformability is also often a feature of complex adaptive systems.

Adaptation is adjustment in the face of change. It may be positive, negative, or neutral. Change may be based on immediate conditions, knowledge of past conditions or new information about predicted conditions. A person, society or species can adapt. As opposed to adaptation, coping is the process of individual intentional change in response to a stressor.

In the resilience literature, vulnerability denotes the opposite of resilience. Vulnerability and adaptation have been used to refer to individuals. Terms such as adaptive capacity, transformability, and robustness, on the other hand, are traditionally used to refer to collectives of decision-making units (villages, cities, nations, etc.). Similarly, individual vulnerability is the antonym of individual resilience. Resilience in this sense means the speed at which a person returns to normal, while sensitivity is the degree of disturbance experienced when facing a certain magnitude of crisis.

Robustness, like resilience, refers to the capacity of a system to continue functioning after experiencing external shocks, but in a short period of time. Resilience, on the other hand, emphasizes learning and transformation that occur over long periods.

THE CONCEPT OF PRIVACY

Thus far, we have delved into the concept of resilience and its diverse range of applications. In this chapter we switch focus to the other fundamental concept in our research, and that is privacy. Chapter starts with a brief overview of different privacy dimensions, before exploring deeper the key aspects of privacy in an online environment. We continue with the presentation of arguments for balancing the need for online information with the need for online privacy. Finally, chapter concludes with elaboration and recent literature of online privacy violations.

DIFFERENT DIMENSIONS OF PRIVACY

The notion of privacy is very individual; it differs from person to person and from one situation to another. Thus, much like with resilience, it is not surprising that privacy is also viewed and researched in many different scientific fields and disciplines. The concept of privacy has also been described through its various dimensions and the approaches may vary depending on the context of studying privacy issues across disciplines.

Among the most cited definitions of general privacy is the one by Alan Westin, who defines it as “claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others”[30; p. 10]. Buchanan et al.[31] go into more detail and emphasize different dimensions of privacy concept: (1) informational privacy refers to a concept of controlling how personal information is collected and used, and is especially pronounced in the digital age when the Internet made personal information easy to collect, store, process and use by multiple parties; (2) accessibility privacy overlaps with informational privacy in cases where “acquisition or attempted acquisition of information involves gaining access to an individual”, but it also extends to cases where physical access is at stake; (3) physical privacy is defined as the degree to which a person is physically accessible to others; (4) expressive privacy “protects a realm for expressing ones’ self-identity or personhood through speech or activity”; and (5) social/communicational privacy refers to an individual’s ability and effort to control social contacts. Similarly, Clarke[32] distinguishes four dimensions of the privacy concept: (1) privacy of the person, concerned with the integrity of the individual’s body, (2) privacy of personal behavior, concerning sexual preferences and habits, political activities and religious practices, (3) privacy of personal communications, referring to the freedom to communicate without routine monitoring of their communications by third persons; and (4) privacy of personal data which covers the issue of making the data about individuals automatically available to third parties.

Past research concentrated on privacy issues from many perspectives (as is to be expected given its broad range of applicability), ranging from defining the meaning of privacy, analysing public opinion trends regarding privacy, evaluating the impact of surveillance technologies, consumers’ responses to privacy concern, causes and different behavior of privacy protection, and the need for balance between government surveillance and individual privacy rights[33]. Previous research has shown differentiated effects on privacy concerns based on various factors such as culture[34], trust in online companies or institutions[35] or different demographic characteristics[23] and personality traits[36].

PRIVACY IN AN ONLINE ENVIRONMENT

Moving on to somewhat more recent concept of online privacy, Gellman and Dixon[37] emphasize the importance of the intertwinement of online and offline privacy issues by noting that what happens offline affects what is done online and vice versa, especially in the age of fourth industrial revolution when the entire supply chains are becoming predominantly digitalized. The Oxford dictionary defines “online” as "controlled by or connected to a computer" and as an activity or service which is "available on or performed using the Internet or other computer network". Similarly, Gellman and Dixon[37] define “online” as connections to the Internet in very broad terms and in its most technical sense refers to computers or devices that connect to the Internet and the World Wide Web.

Online privacy has a different dynamic than offline privacy because online activities do not respect traditional national and/or conceptual borders. Online privacy involves the rights of an individual concerning the storing, reusing or provision of personal information to third parties, and displaying of information pertaining to oneself on the Internet. In the digital era, the online privacy concept focuses on personal information shared with family, friends, businesses, and strangers, while at the same time engaging in self-protection of sensitive information[13]. Before the digital era, securing personal information and maintaining privacy simply meant safeguarding important documents and financial materials in a safe “material” place, but with the rise of the Internet, an increasing amount of personal information is available online and vulnerable to misuse. Even a simple online activity such as using various search engines can be potentially misused for consumer profiling. Reed (2014) coined the term “digital natives” to describe new generations of children who have grown up with the Internet as a presence throughout their entire lives and are accustomed to these online activities from very young age. However, Walther[38] emphasizes that most people, including these “digital natives”, fail to realize that, once uploaded, information stays online more or less forever, and as such can be retrieved and/or replicated, despite subsequent efforts to remove it.

Finally, it is important to distinguish between concepts of privacy and data protection. European Commission[39] defines data to be classified as personal data for “any information that relates to an identified or identifiable living individual. Different pieces of information, which, collected together, can lead to the identification of a particular person, also constitute personal data. Personal data that has been de-identified, encrypted or pseudonymised, but can be used to re-identify a person, remains personal data and falls within the scope of the GDPR.” Furthermore, under Article 4 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), personal data is defined as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (“data subject”); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.” Currently, data protection is believed to be the most critical component of privacy protection as more and more aspects of everyday lives are being automated and digitized.

BALANCING THE NEED FOR ONLINE PRIVACY

In a modern society, privacy is recognized as an individual right, but also as a social and political value[40, 41]). With the coming of the fourth industrial revolution and the emergence of technology-based surveillance, a galloping volume of online transactions and usage of private client data in developing business strategies, both state and private sector are holding, processing and sharing a large amount of personal information. Thus, many governments have put in place privacy protection policies to meet the demands for safety, security, efficiency, and coordination in the society. The flip side of this coin is that governments themselves, in the process of securing individual privacy, might gain too much power over individuals in terms of profiling behavior and purchasing habits. Thus, there is a certain need to balance the privacy of individuals against the legitimate societal need for information[42]. For this need to be positively perceived in the eyes of the public, it must be done in a professional and transparent way. Adding to this debate, Smith, Dinev and Xu[43] explain two interesting concepts: privacy paradox and privacy calculus. The former is a phenomenon where an individual expresses strong privacy concerns, but then behaves in a contradictory way, for example, by sharing personal information online. On the other hand, privacy calculus can be explained as a trade-off between privacy concern “costs” and “benefits” in the form of the service obtained. Rational expectations theory in this concept states that users are willing to disclose personal information if their perceived benefits outweigh the perceived privacy concerns.

Solove[40] argues that in a modern society the value of privacy must be determined based on its importance to society, and not in terms of individual rights. Goold[44] argues that citizens would demand a decrease in state surveillance if they perceived it as a threat to their political rights and democracy in general. Several articles have also shown that privacy concerns or previous privacy violations act as a hindrance to the growth of e-commerce[45]. Companies have realized that protecting consumers’ private information is an essential component in winning their trust and is a must in facilitating business transactions[46]. Wirtz, Lwin and Williams[47] indicate that citizens who show less concern for internet privacy are those individuals who perceive that corporations are acting responsibly in terms of their privacy policies, that sufficient legal regulation is in place to protect their privacy, and have greater trust and confidence in these power-holders.

PRIVACY VIOLATIONS ONLINE

Privacy violation is a stressful event in which occurrence cannot be predicted in a specific point in time and its scope and consequences are not known in advance. Like the concept of privacy, the concept of privacy violations is extremely difficult to measure, as an individuals’ subjective notion of online privacy violation is complex, and it differs across different individuals. Increased demand for information and the spread of new technologies that gather personal information indeed limit the purely private spaces and increase the number of privacy violation cases. The violation of privacy on the Internet includes change in the privacy norms i.e. what information is gathered, how information is used, and with whom information is shared[48, 49]. However, perceptions of privacy violations can be very subjective and therefore difficult to be legally defined and protected, especially when it comes to implementation[50].

Online privacy violations became a real threat that should be addressed by both the government[51] and businesses[52] in order to increase trust of consumers and downgrade the perceived risk[53]. Since the offset of the fourth industrial revolution, information privacy has been in the focus of e-commerce and marketing strategies towards consumers, as online companies want to collect consumer information (often times not allowing them to proceed with their purchase without providing some sensitive personal information), and consumers often view this practice as a privacy violation[54].

While privacy theft can be carried out on the systems that are easily fooled by spoofing[55], these thefts have a large impact on consumers’ feeling of security. Information privacy concerns and violation present a significant obstacle to more people engaging in e-commerce[56]. There is also an enormous impact if consumers’ financial position is affected from the privacy theft, for example by unauthorized online payment. These situations occur because traditional online payment systems (e.g. banking) require a consumer to be authorized using only his/her own information, such as a username and password[57]. To tackle this problem, new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be leveraged to secure consumers’ positions on the market, as well as their identity[58].

As a response to previous privacy violation experiences or as a means of preventing privacy violation, individuals adopt different strategies to make them more secure online. Gurung and Jain[59] list the suggested typologies of individuals regarding their online privacy violations: (1) privacy aware, referring to being knowledgeable and sensitive about risks associated with sharing personal information online; (2) privacy active, referring to active behaviors adopted by consumers in regards to their privacy violation concerns; and (3) privacy suspicious, referring to concerns about particular company’s or individual’s behavior regarding their privacy practices. In terms of protection against privacy violation, Yao[60] and Gurung and Jain[59] posit that, from an individual perspective, it can be either passive or active. Passive protection involves reliance on a government or other external entities, and it is beyond the direct control of an individual. The level of this protection is also dependent on collective actions and institutional support, as well as on cultural and socio-political norms. On the other hand, active protection relies on individuals themselves actively adopting various protective strategies. Examples of these strategies may include abstaining from purchasing, falsifying information online, and adjusting security and privacy settings in the Internet browsers[61].

COMBINING RESILIENCE AND ONLINE PRIVACY VIOLATION

After introducing and discussing the concepts of resilience and privacy violation of consumers in an online environment in previous two chapters, this chapter aims to connect the concepts of resilience and online privacy violation from the point of consumer living in age of high digitalization of entire value chain.

Proposed research of consumer resilience to privacy violation online is exploring resilience at the intersection of an individual and psychology, and in engineering contexts. To assess this research issue, one should examine the capacity of an individual to recover from adversity, depending on their individual characteristics and their environment. In the specific context of exploring resilience to online privacy violation, it should be considered that resilient individuals possess three common characteristics: an acceptance of reality, a strong belief that life is meaningful, and the ability to improvise[62]. Thus, one should consider definitions from organizational and disaster management pointing out the importance of the period of regressive behavior, as well as accounting for previous experiences.

From an individual’s point of view, resilience is an interactive concept that is concerned with the combination of serious risk experiences and a relatively positive psychological outcome, despite those experiences[63]. Early studies on individual resilience focused on child development in adverse settings, especially poverty, where the traditional approach included identifying risk-factors. The risk-approach aims to identify psychological, familial, and environmental factors to reduce these risks. Consumer behavior is inevitably determined by psychological factors. Application of resilience in psychology can be found in two streams: one originating from the study of the impacts of crises and abrupt changes that impact families; the other looks at child development after a traumatic event. In developmental psychology, to determine resilience one chooses outcomes and risk factors to be measured. In some studies, resilience is observed if good outcomes are achieved despite the threats to adaptation or development. However, defining what is good or normal is not precisely set. Studying resilience as a positive adaptation in the context of significant adversity seems to be more applicable to different psychology research. Resilience is then defined as an ongoing process of continual positive adaptive changes to adversity, which enable future positive adaptive changes. Such a definition assumes bidirectional interactions, as well as recognition that history, including previous adaptations, determine (positive) adaptive outcomes. Since the introduction of adversity and positive adaptation concepts to the resilience literature[10,64], most researchers agree that, for resilience to be demonstrated, both adversity and positive adaptation must be evident[63].

Once the wide variety of resilience concepts across disciplines and practical applications have been introduced, the principal question is which field of resilience is appropriate to research consumer resilience to online privacy violation, so naturally one has to look back at the research of resilience in social sciences. Raab, Jones and Székely[65] explore societal resilience to the threats to democracies posed by the current mass surveillance of communications and other applications of surveillance technologies and practices. The authors use an example of public goods to illustrate the distinction between the concepts of resistance and resilience: resistance prevents deviations from the ideal state (so no recovery is needed), while resilience helps to recover after stress provided that deviation from ideal state has occured. In distinction to resistance which implies invulnerability to stress, resilience implies an ability to recover from negative events and the ability of a system to experience some disturbance and still maintain its functions. There are two possible outcomes of resilience: full recovery, which is the return to the previous ideal state, and partial recovery, where the real state after recovery is not equal to the ideal state before the shock.

Two streams of research are particularly important for the context of consumer resilience to online privacy violations. The first stream explores the complex inter-relationship between privacy and system resilience, i.e. resilience is here conceptualized at the system-wide level, ranging from small information systems to the entire social system. Studies within this research stream mainly deal with the question of how to maintain resilience of the system when its privacy is endangered[66]. Another related field of research, with the same system-wide conceptualization of resilience, explores the relationship between surveillance and resilience, and how surveillance (and privacy as its antipode) contributes to or hampers resilience of societies to various threats[65,67].

The second stream of research deals with consumer behavior and resilience on an individual level, which is the stream where we position this research as well. Studies within this body of literature, although still rather rare, conceptualize resilience at the individual level and explore how consumers recover or adjust their consumption habits after experiencing some form of adversity situation[7,68]. These studies explore resilience at the individual level and conceptualize it as the capability of individuals to recover from or adjust to various adversities and misfortunes or as the process of adaptation to adversity[10,11,69].The main fields that apply this conceptualization of resilience are psychology, medical sciences, criminology, social work, and business studies[7].

Literature on consumer behavior is abundant (for a historical overview see Solomon et al.[70]) and more recent studies explore consumer behavior in an online environment[71,72,73] that gains importance due to the development of the online marketplace. Recently, Islam[74] stated that cultural and social factors, demographics, motivation, perceived risk, trust, and attitude of consumers all affect their buying intentions online. However, behavior consequences, which are more complex in the online environment compared to offline, remain under-explored[75]. National and local governments across different countries are continuously adopting digital technologies in different spheres, from collecting data to providing different digital services with the goal of improving the quality of citizens’ lives. In this context, citizens’ concerns about online privacy and their behavior are different depending on the kind and purpose of data collection[73]. In addition to that, digitalization raises consumer protection issues for the future development and implementation of e-services in the public sector or implementation of the smart city concept[76], and requires improved consumer skills, awareness, and individual engagement that would result in sustainable buying decisions[77]. Twenty years ago, back in 1999, consumers were not willing to provide personal information online when asked, and this rate exceeded 95 %. This rate was highly affected by the privacy concerns, which was in turn highly influenced by skills of consumers[78]. As complexity for protecting of the digital consumer rose, movements for simplifying and defining explicit statements on how consumer data will be used and directives on how to improve consumer skills increased[79]. Internet skills diminish as the population age increases, and that affects overall consumer activities over the Internet[80]. An important characteristic of digital consumerism is that digital goods are not effective for structuring social relationships, as everyone can have everything[81].

FRAMING FUTURE RESEARCH

In the previous chapter we have combined the notions of resilience and privacy violation online. This chapter aims to set grounds and offer suggestions for future development of both conceptual and empirical research frameworks to assess consumer resilience to online privacy violation.

To assess consumer resilience to online privacy violation, one should find an appropriate theoretical concept and proceed with building and testing the developed model. Research on consumer resilience to online privacy violation should borrow and adapt theoretical concepts used in studying resilience in diverse academic disciplines. Researchers should primarily consider approaches used in resilience of individuals, considering individuals’ protective factors in addition to risk factors. Individual resilience is not only determined by relatively rigid personality characteristics, but it also to a greater extent affected by broader micro- and macro-environmental factors.

Previous studies that explored resilience at the individual level identified several contributing factors or antecedents that lead to resilience[5,82]. Some of personal antecedents to resilience include various psychological attributes (personality traits, locus of control, self-efficacy, self-esteem, optimism)[82, 83] while others are socio-demographic factors, such as age, gender, education[84, 85]. Carver, Scheier and Segerstrom[86] have identified optimism as an individual difference variable that reflects the extent to which people hold generalized favorable expectancies for their future. Also, different aspects of psychological well-being should be analyzed and related to different aspects of resilience because those who have higher resilience are effective in improving psychological well-being[87. Finally, there is evidence that personality traits in general have high impact on resilience. Some studies showed that among different personality factors, honesty, humility, and openness to experiences occurred in a stressful situation prior to other personality factors, thus affecting the development of resilience, while extraversion and agreeableness affected innate and acquired resilience.

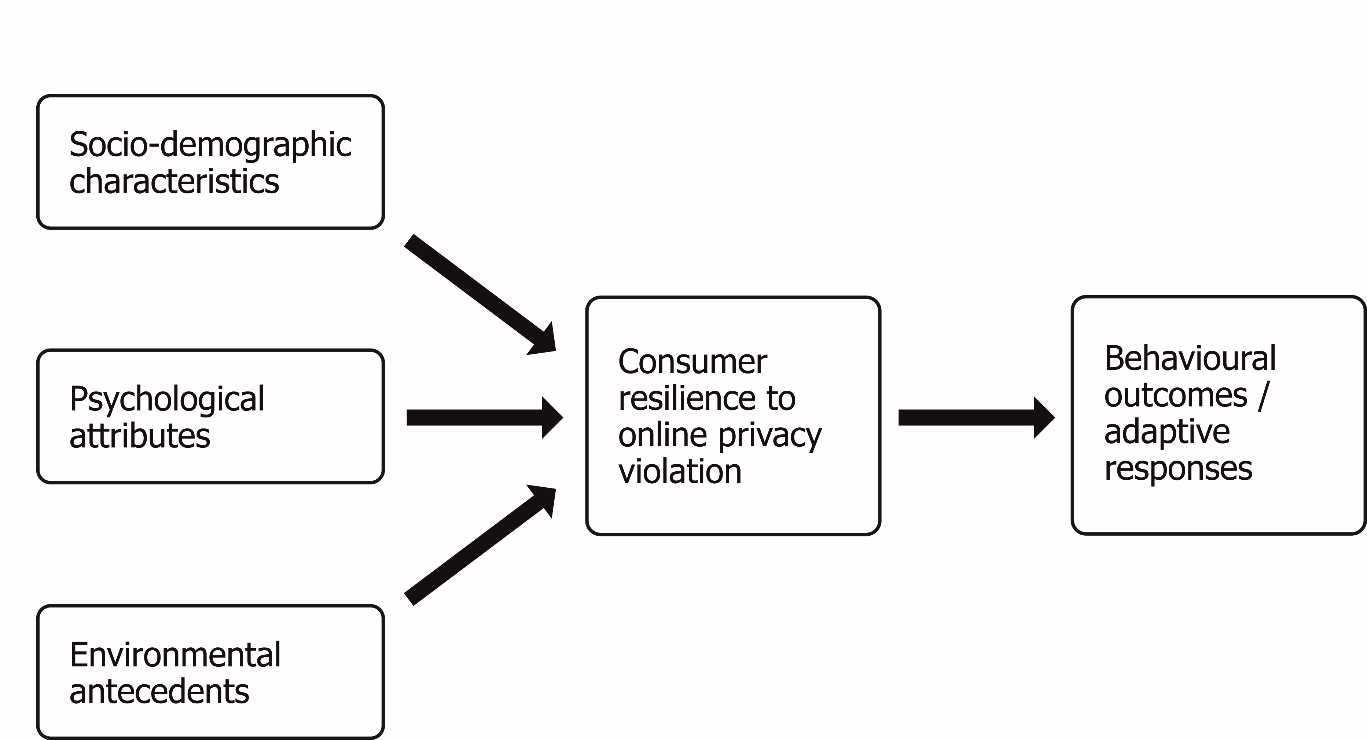

Environmental antecedents to resilience should include various micro-environmental factors (social support, family relationships, peers, stability), as well as macro-environmental factors (community, institutions, cultural factors) that affect resilience[10]. Three elementary groups of antecedents of consumer resilience to online privacy violation are shown on Figure 1.

Resilience differs from traditional concepts of risk and protection in its focus on individual variations in response to comparable experiences[63]. Accordingly, the focus of future research needs to be on those individual differences and causal processes that they reflect, rather than on resilience itself as a general quality.

There are two sets of research findings that provide a background to the notion of resilience. First, there is the universal finding of huge individual differences in people’s responses to all kinds of environmental hazard. Before inferring resilience from these individual differences in response, there are two major methodological artefactual possibilities that have to be considered. To begin with, apparent resilience might be simply a function of variations in risk exposure. Resistance to (environmental hazards) may come from exposure to risk in controlled circumstances, rather than avoidance of risk. This possibility means that resilience can only be studied effectively when there is both evidence of environmentally mediated risk and a quantitative measure of the degree of such risk. The other possible artifact is that the apparent resilience might be a consequence of measuring a too narrow range of outcomes. The implication is that the outcome measures must cover a wide range of possibly adverse consequences. Second, there is evidence that, in some circumstances, the experience of stress or adversity sometimes strengthens resistance to later stress— the so called ’steeling’ effect. Although literature on individual differences in response to environmental hazards is more abundant, there are some empirically-based examples of stress experiences increasing the resistance to later stress. Risk and protection both start with a focus on variables, and then move to outcomes, with an implicit assumption that the impact of risk and protective factors will be broadly similar in everyone, and that outcomes will depend on the mix and balance between risk and protective influences. Resilience starts with a recognition of a huge individual variation in people’s responses to the same experiences, and considers outcomes with the assumption that an understanding of the mechanisms underlying that variation will cast light on the causal processes and, by so doing, will have implications for intervention strategies with respect to both prevention and treatment.

Adaptive responses of resilient individuals to various adversities and misfortunes are mainly explored in literature as possible indicators of resilience[88, 89]. Specifically, in the context of resilience in research on consumer behavior, the concept of adaptive responses is not developed. The closest concept that might be applied is that of adaptive capacities which include preventive strategies to avoid event and impact-minimising strategies, which seek to facilitate recovery[90].

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this article is to develop the future research frontiers in investigating consumer resilience to online privacy violation. Therefore, a range of the theoretical concepts that might be applied in the research of consumer resilience to online privacy violation are examined. Based on the non-systematic literature review we conducted mainly on resilience and to a lesser extent on consumer behavior theory, we came to the proposal of a conceptual model of consumer resilience to online privacy violation. The model should be based on the premise that after the stressful event individual consumer is acting differently than before this adverse event. A set of individual socio-demographic characteristics as well as micro- and macro-environmental conditions affect the specific consumer resilience to privacy violations, and in turn affect their behavior outcomes.

Distinctive to the resilience concepts applied in investigating system resilience, resilience in disaster management, in ecological or psychological fields, resilience of organizations and other resilience domains, this article proposes an interdisciplinary approach to assess resilience of consumers to online privacy violation. Compared with the previous research, we offer a unique research approach to this new and unexplored aspect of consumer behavior in the digital environment.

The article has practical implications for researchers. The model that would include a set of individual characteristics and environmental variables will contribute to the existing understanding of resilience at the intersection of psychology, economics, and privacy studies. Furthermore, it will also contribute to the understanding of adaptive responses of resilient individuals to privacy breaches in an online environment, as well as to the understanding of processes by which resilience affects adaptive responses of individuals in the specific context of online privacy breaches.

This study is not without limitations and open questions for future research. Firstly, a very practical limitation was that it was not feasible to incorporate all the resilience theoretical contributions from all resilience domains in this review. Secondly, during future selection and testing of the prospective variables to enter our conceptual model, researchers could get additional insights in the resilience, privacy online and related consumer behavior, and thus amend this model with new variables. Finally, this model is set to analyse online privacy violation effects on consumer future behaviour (via their degree of resilience), while these adverse events many also have other spill over effects to consumers themselves and to their closer circle of relatives and friends, which are currently not included in the proposed model. The future research implications stem from the fact that the extant resilience literature is scarce in empirical analyses and mostly based on the case studies and to a lesser extent to surveys. The survey of Internet users having experienced the privacy violation online would be an appropriate data collection method and the structural equation modelling could serve the most appropriate to test the relations in the model.