Introduction

Alcohol consumption is a social phenomenon. It is a phenomenon that depends on society: it takes place in society, it is realised by society, but also for society. When we speak of the dependence of alcohol consumption on society, we frame this phenomenon within the regularity of a certain social structure. The values and norms of society form a social space in which individuals consume alcohol (among other things). By regulating how much alcohol should be drunk, which alcoholic beverages should be consumed on which occasions, and with which situations alcohol consumption is associated (how much alcohol is consumed in certain situations), a symbolic dimension of alcohol as a substance is achieved in the context of social life. These social frames (values and norms) determine in some way the social life of an individual. It becomes part of social interaction – alcohol consumption tends to occur when the individual is not alone (and when one does it alone, it is often in the context of reflecting social knowledge that is positively opposed to drinking). However, the viability of alcohol consumption does not depend solely on its value. For alcohol to be a part of social interaction, and thus for socially conditioned rules to be applied, an individual or a particular social group must understand the meaning of their actions. It is only through this repetition that the social meaning of alcohol consumption is realised in social interaction – it becomes a kind of social fact. It is precisely this interplay of value system and interaction that is the key to the social realisation of this phenomenon. Society determines alcohol consumption, but through this determination, alcohol consumption becomes part of the interaction ritual that achieves certain elements of social integration (but also disintegration) in everyday life. In a way, alcohol consumption and its social significance are founded on the interplay of both structure and agency.

This brief introduction opens a space for a sociological reflection on alcohol consumption. It is at this point that the main question of this paper arises. How can we approach alcohol consumption sociologically – what sociological tools or paradigmatic frameworks can explain how alcohol consumption finds its place in social life? To answer this question, some of the basic approaches to the sociological study of alcohol consumption are presented. These approaches are critically reviewed, and finally, a theoretical, sociological starting point for considering the social aspects of alcohol consumption is proposed. The reason for this objective, which aims to provide an answer to the theoretical assumptions of the sociology of alcohol consumption , lies in insufficiently developed or too specific theoretical concepts (despite the large number of sociological studies on the subject). As far as the social aspects of alcohol consumption are concerned, the empirical material does not rely on a specific sociologically grounded theory of alcohol consumption, thus remaining in the realm of what Mills (2000) calls abstract empiricism ─ a moment in the development of sociology in which method is fetishised by sociologists to the detriment of the sociological imagination (seeMills, 2000: 50-75). Now, abstract empiricism is only one of the possible extremes in sociology. There is also a critique (inMills, 2000) of grand theory sociology. As our statement could fall into the second category (without the empirical background of this introduction), it is important to add those concrete empirical aspects of our arguments, which will be presented later in the text.

Sociological Approaches to Alcohol Consumption

The sociological study of the phenomenon of alcohol consumption has often focused on the analysis of excessive alcohol consumption or alcoholism. Alcohol consumption itself has been considered in the context of potential risks of alcoholism or deviance caused by excessive alcohol consumption. An example of this type of attitude can already be found in the works of one of the classical sociologists. In his study of suicide, Durkheim (2005) examines the hypothesis of the relationship between the rate of suicide and the rate of alcohol abuse in certain societies (a term used in the context of the time in which Durkheim was active). He rejects the hypothesis in his research and concludes that there is no significant relationship. This approach was also one of the first approaches to alcohol consumption within sociology as a science. However, it is related solely to determining the relationship between deviant drinking (alcoholism) and suicide. Thus, alcohol consumption was not the immediate focus of research interest.

In contrast to Durkheim, other classical sociological theorists (Weber, Simmel, Tocqueville and Marx) did not consider alcohol consumption as a relevant sociological phenomenon in their works (seeBrezovec, 2021). The fact mentioned, however, does not in any way constitute a criticism of the failure to mention alcohol consumption as a part of society within classical sociological theory. Classical sociologists had the main task of defining the basic principles for the study of social life and social structure. They had to establish sociology as a science. Phenomena of everyday life, such as alcohol consumption, were not crucial to such “big questions” and the establishment of sociological principles. One could say that everyday questions – for example, the relationship between society and alcohol consumption – are a privilege of modern sociologists, made possible precisely by the elaboration of the discipline, which is the legacy of classical sociologists.

This changed with the works of Selden Bacon. Selden Bacon (1943) was one of the first sociologists to take a step further in his reflections on alcoholism and excessive drinking. He presented alcohol consumption as a relevant sociological phenomenon. For him, it was an issue that sociology had to address. It was the task of sociology to explore the ways in which alcohol consumption permeated social life – for example, how different cultures dealt with alcohol consumption, where the threshold of tolerance for excessive drinking and alcoholism lay, and for what reason.

That sociology was literally sociological because it centred on the social, societal, and cultural aspects of drinking. With that approach, sociologists shifted their focus from looking exclusively at alcoholism to looking at the culture, patterns, and norms of drinking. In that line of thinking, alcoholism was viewed as a phenomenon that was social in its roots (its ethos was social). In other words, alcoholism was just the tip of the iceberg, and sociology as a discipline had to dive below the surface and see what it looks like underwater and how deep the problem is. Yet even in this sense, the sociology of alcohol consumption, though broadened by social context, remained trapped by focusing on alcoholism and excessive drinking as exclusively negative features of the relationship between society and alcohol.

Thus, despite his idea, Bacon's studies, as well as other studies of alcohol consumption, focused primarily on examining the social aetiology of alcoholism rather than attempting to actually understand everyday (in many cases socially functional) drinking and its significance to the individual and society. Selden Bacon, as well as others who have studied the sociology of alcohol use, did not move away from what had been termed the problem-oriented approach (Levine, 1991 inFreed, 2010). This sociological problem orientation involves, on the one hand, the search for the social aetiology of alcoholism and excessive drinking and, on the other hand, the detection of social pathologies that are a direct or indirect result of both normalised and excessive or pathological drinking. For example, Ullman (1952) studied the difference in drinking between alcoholics and non-alcoholics (see Ullman, 1952 inFreed, 2010). Ullman discussed these differences to facilitate explaining the pathology of alcoholism (already accepted as a disease). To further support the argument of a problem-oriented approach, we can mention the work of Bucholz and Robins (1989). The opening sentence of their paper's abstract is as follows: This review of sociologically relevant alcohol research addresses definitions of alcohol problems, describes patterns and trends in adult drinking practices and problems and correlates of alcoholism, and describes social policy responses to alcohol. (Bucholz and Robins, 1989: 163).

This, however, does not mean that Bacon or other authors who addressed alcohol consumption sociologically did not see the ritualistic dimension of alcohol consumption, or the connection between sociability and consumption. They perceived alcohol consumption as a relevant social phenomenon that could shape the reality of the situation. However, their approach did not provide a relevant sociological episteme that could lead further research. They detected some aspects of the problem (despite their problem-oriented approach) but had no systematic insight into the phenomenon itself. That further enhanced the retention of the entire field of sociological study of alcohol consumption in the area of alcoholism.

In this way, a whole theoretical tradition of the sociology of alcohol consumption has emerged – for example, Bales and his studies of sociocultural differences in the degree of alcoholism (1946), Perlin and Radabaugh and their definition of alcoholism as a kind of escape from the problems caused by economic regression (1976).

It is important to emphasise, however, that these studies have made a valuable (but limited) contribution to the understanding of alcohol consumption and alcoholism in different societies. For example, such studies can reveal more about the relationship between crime rates and alcohol consumption (Lenke, 1982), gender inequalities in alcohol consumption – alcohol is consumed more often by men than by women (Dawson and Archer, 1992: 122), socio-economic inequalities as a factor in excessive alcohol consumption (lower socio-economic status is associated with more frequent excessive alcohol consumption) (Huckle, You and Casswell, 2010: 1201). All these studies have confirmed certain associations between social actors or phenomena on the one hand and excessive alcohol consumption on the other. All this research has confirmed the sociological relevance of alcohol consumption but has not yet provided a relevant theoretical basis for a full understanding of the phenomenon. In order to understand the social aspects of alcohol consumption, there is a need for an epistemological model that could steer the explanation of purely empirical data towards a sociological theory.

However, this idea of systematising and seeking an epistemological basis for sociological approaches to alcohol consumption is not new. In order to somewhat put in order the sociological history of alcohol consumption, Freed (2010) defined three basic sociological research perspectives or starting points: (1) sociocultural perspectives, in which the dimensions of knowledge, values, and norms that determine society's approach to alcohol use can be found, (2) socio-ecological perspectives, which analyse the ways in which social learning is linked to understandings of alcohol use, and (3) ideological perspectives, which aim to examine the implementation of a discourse that defines alcohol use as a desirable or undesirable characteristic of a society (Freed, 2010: 3). But the consideration of these approaches (as Freed notes) brings us back to the fact that they all use the social context of alcohol consumption as a means of explaining addictive behaviour in the future, so the final conclusions are in the service of considering mainly the dysfunction, and not the functionality of alcohol use for society.

Epistemological Problems of the Sociological Studies of Alcohol Consumption

According to our thesis, three fundamental problems can be identified within the sociology of alcohol consumption. The first problem has already been outlined and relates exclusively to the focus on alcoholism and/or excessive drinking . Even the consideration of so-called recreational drinking is in the service of future aetiological explanations of alcoholism. Thus, the social aspects of the phenomenon are subordinate, i.e., they are not the proper target of study. Within such an approach, the study of the social context of drinking is only a tool for understanding addictive behaviour. It only needs to be understood in order to understand other phenomena.

Another problem is that the sociology of alcohol consumption relies heavily on method and empiricism. Understanding the social dimensions of alcohol consumption is not brought into focus through theoretical consideration of the results but through empirical findings alone. In sociological research on the relationship between society and alcohol consumption, the empirical data mostly stand alone, without an accompanying theoretical definition of drinking. Thus, the sociology of alcohol consumption falls within the framework of abstract empiricism. The most important thing in this type of study (which is identified as a problem in this paper) is the discovery of possible empirical relationships between various social phenomena and alcohol consumption. Theoretical conclusions or the formation of a theory about the social meaning of alcohol consumption, as well as a basic theoretical conceptualisation of the research, are missing or are set in the text just at a declarative level (seeLennox et al., 2018;Buvik, Moan and Halkjelsvik 2018). These claims can be supported by concrete research. For example, Aghi, Dahlberg and Lennartsson (2019) examined the relationship between social integration and alcohol consumption among the elderly population in Sweden. The research identified relevant empirical indicators. Indeed, sociability could be associated with a higher frequency of alcohol consumption in this population. Apart from the empirical material, the elaborated methodology and the results presented, there is no theoretical basis anywhere in the text. The empirical data stand on their own and for themselves. Similarly, the research mentioned earlier problematises alcohol consumption in relation to other social phenomena and/or issues without a proper theoretical background or conclusion. This is the case with some other studies on the social aspects of alcohol consumption (seeGohari et al., 2020;Davoren et al., 2016).

However, it is important to mention that there are new orientations within the sociology of alcohol consumption that point out the theoretical basis as something that should be primal in defining the social aspects of the phenomenon. An example is the study conducted by Thurnell-Read (2021), who investigates the social significance of pubs as a form of social space that enables sociability. More importantly, he investigated the ways in which this form of social space is achieved (using qualitative methodology). Another example is the work of Karlsson, Holmberg and Weibull (2020). They investigated the acceptance of alcohol-related policies in Sweden. They used a very broad theoretical tool to define the research problem – reaching from self-interest theories, ideology theories, knowledge and problem perceptions. Their conclusions are theoretically founded. They found the connection between support for restrictions on alcohol consumption and ideological aspects of life (norms and values relating to alcohol in everyday life) (Karlsson et al., 2020: 118).

To be more precise, in recent studies on alcohol consumption there is a significant trace of theoretical foundations, but they lack a clear epistemological point from which a sociological study of alcohol should start. From that, a third problem arises. In the absence of clear theoretical definitions and with its focus on problematic alcohol use, the empirical work of sociologists on alcohol consumption seems ancillary to professions and disciplines that deal with alcohol more intensively and comprehensively (both in terms of theory and empirical research). Thus, in this sense, sociology is a companion, auxiliary discipline for those concerned with the treatment, treatment methods, rehabilitation, and resocialisation of alcoholics.

Without a clear episteme on which to base sociological work on alcohol use, sociology and its study of alcohol use cannot be independent of other disciplines. This is the third problem with the sociology of alcohol use. Other disciplines give scientific as well as pragmatic meaning to this sociological knowledge. For this very reason, it is not surprising that topics related to alcohol consumption have not entered the so-called mainstream of special sociologies within the sociological community. This has already been noted by Blum (1984), who points out that the majority of sociological papers on alcohol and/or alcoholism have not been published in relevant sociological journals. Considering the way in which sociology has so far researched alcohol, one can get the impression that sociology is indeed an ancillary discipline and in itself does not explain the crucial issues that sociology should investigate when it comes to alcohol consumption – relations between society and the phenomenon – regardless of its functionality or dysfunctionality in the medical sense. Thus, papers on the relationship between society and alcohol consumption might be rejected by the relevant sociological journals because of an inadequate sociological approach or even because the topics are not clearly sociological.

Theoretical Assumptions of Sociological Studies on Alcohol Consumption

As mentioned in the previous part, one of the fundamental points for the sociological study of alcohol consumption in Bacon's works is that alcohol consumption is a part of social life and is subject to social norms, values, expectations and sanctions. So, to explain deviance, we need to detect the cause of deviant drinking. Alongside this point of view, a generally accepted position, taken by other disciplines as well, is that a certain drinking culture determines the direction of future and potential deviations. Thus, in psychiatry, the concept of drinking culture is often mentioned when conceptualising the problem of alcoholism and excessive drinking. Savic et al. (2016), noticed a significant increase in mentions of drinking culture in the SCOPUS database since 2000, and also pointed out that this concept had remained relevant. However, in a large number of papers, this term remains only a meta-term that defines the undefined. In other words, drinking culture is defined as norms of drinking (Mizruchi and Perruchi, 1970), values attached to drinking (Room and Mäkelä, 2000), drinking habits (Ahlström-Laakso, 1976), etc. (seeSavic, et al., 2016: 270-282) These habits, values and norms remain undefined. This undefined drinking culture can practically be understood by common sense, and therefore has become a key point for defining the aetiology of alcoholism.

But can this concept be a vehicle for sociological theoretical constructs of alcohol consumption? In its broadness and indeterminacy, it can support work that moves towards abstract empiricism (where a theoretical construct is set pro forma regardless of its functionality and reflection in reality). Indeed, the goal of the notion of drinking culture encompasses (drinking) culture in the broadest sense of the word, something that an individual possesses and uses to organise their daily life. Culture in this context means the process of civilising (ennobling) man (Busche, 2000: 69-90). In these terms, alcohol consumption reflects the socialisation process of any individual. However, this process of cultivating drinking within an individual and in the broader social context is not unique, but consists of a number of different patterns, some of which are in contradiction with others (and in this contradiction, they form the uniqueness of the social understanding of alcohol). In other words, this drinking culture depends on the situation and the way the individual copes with it (but also on the habitus of the individual in a given society). The insistence on using the term “drinking culture” also excludes sociological concepts such as the interplay of roles, the dimension of power, and social inclusion or exclusion due to alcohol consumption (or a lack thereof).

However, if drinking culture as a basic concept is not precise enough to create a sociology of alcohol consumption, where to start? How to establish a theory useful for a further conceptualisation of research and understanding of this phenomenon in synthesis with empirical data? Where should one begin the search for such a theory?

A possible solution for the theoretical approach to alcohol consumption can be found in the dual process models. Lizardo et al. (2016) noted that the idea of capturing the link between values and actions can lead to a more concrete approach to cultural phenomena. Although the DPM is an interdisciplinary approach, Lizardo et al. (2016) believe that it could benefit sociological research and theory in a particular way. Their paper even cites alcohol consumption as an example of how to carry out the proposed method in a certain way. Alcohol consumption is mentioned in their third domain of DPM – culture and thinking. They consider alcohol consumption a cultural phenomenon that forms a specific area for an individual to process the performance of an action. However, for them, the example of alcohol consumption is a kind of critique of the model, as it has very high variability in everyday life. According to them, the DPM approach to culture and thinking should always be based on empiricism rather than remain only an analytical tool (Lizdardo et al., 2016: 299). The main direction of their approach is valid considering the general idea of connecting the macro- and microbase of society, but do we need to look beyond our own discipline to find a solution? Is it not enough to look at the canon of sociology to see that this kind of epistemological basis has been around since Weber and even Durkheim? The link between action and structure is important, but it can be achieved within sociological theory and method. By accepting the psychological tools, we accept their paradigmatic approach, which focuses more on individual cognition than on the individual as an embodiment of the social. The field of study of sociology is the social sphere, not the individual. Action, thought, and reflexivity are important if they can provide us with the manifestation of some social phenomena. In our own example, we follow the same direction as Lizardo et al., but we use methods that are traditional in the sociological paradigm.

However, here we must ask ourselves what theoretical or even paradigmatic approaches within sociology (if we accept the assumption that sociology is a multi-paradigmatic discipline – seeRitzer, 1975: 156-167) can successfully express the sociological approach to alcohol consumption. First, there is the question of where and in what ways alcohol consumption occurs. Alcohol consumption is inextricably linked to society and the individual. It occurs in concrete situations in its social form, but also in its individual internalisation of meaning. Therefore, it is inseparable from the individual's social actions, but also from their knowledge of the situations in which they find themselves. Alcohol consumption without agency, that is, without a series of individual social actions does not exist as a phenomenon. The social aspect determines alcohol consumption, and this is recorded through the individual's rational action (be it axiological or instrumental rationality, which in a general sense can be presented as ordinary rationality: seeBoudon, 2011: 33-49). Further elaboration may consider the theoretical assumption that human action in society is a fundamental determinant of the sociological theory of alcohol consumption. Here it can be seen that the approach is Weberian in the sense of verstehen sociology. However, in order for a conceptual insight into alcohol consumption to be more theoretically grounded, this verstehen sociology needs to be discussed further. It is necessary to establish a sociological theoretical-methodological approach to this topic in order to construct a stable theory of the sociology of alcohol consumption and to contribute to empirical work regarding the relationship between the individual, society and alcohol consumption.

The present work follows the tradition of interpretive sociology, which in its principles proceeds from the individual, through their activities in the community to broader, societal activities (Weber, 1989: 159). But the individual here is only the starting point from which the whole society is understood. This does not mean that the individual determines society (nor, conversely, that society determines the individual), but that a broader social phenomenon can be understood by observing individual rational actions (whichever rationality is taken into consideration). This legacy of sociological understanding lives on in the basic assumptions of methodological individualism and methodological situationism. It is these approaches, as contemporary successors to verstehen sociology, that can help establish the sociology of alcohol consumption in a unique paradigmatic setting – starting from the microlevel or within the framework of everyday life.

The Principle of Methodological Individualism in the Sociological Theory of Alcohol Consumption

Before proceeding to the analysis of the applicability of methodological individualism when considering the social occurrence of alcohol consumption, it is necessary to briefly describe the basic determinants of this theoretical tool. This approach has its origins in Weber's sociology. In his work “Economy and Society” (2019 [1922])), Weber points out for the first time that in explaining social phenomena, sociology must focus on the individual since the totality of individuals' actions constitutes a particular social relationship. An individual is an internalised society. Within the individual lies an understanding of how and why one should do something in society. This understanding and the socially based intentionality of action can show the sociologist the shape of broader social phenomena.

If we take back Weber's conception of this methodological tool, we find that it is a useful method for understanding social life (Weber, 1989: 162-163), which is based on the understanding of the individual as a kind of a particle of society (Udehn, 2002: 485). A kind of social code of society is woven into the actions of the individual. Thus, methodological individualism does not imply that an individual forms a society, but through this principle, the social patterns of meaning and rationality formation in the individual are revealed. These principles of methodological individualism are applicable to alcohol consumption in that they start from the assumption that in order to understand the broader social picture and perception of alcohol consumption, it is necessary to explore the specific, socially based motives that support an individual in deciding whether or not to consume alcohol. Thus, to discover the social dimensions of alcohol consumption, one must start from the individual and their actions. An individual attaches a certain meaning to alcohol consumption. This meaning is not to be understood exclusively as the subjective experience of the individual, but as a synthesis of the individual’s subjectivity and the social patterns they internalised. No one consumes alcohol until they have learned how and why to do it. When speaking of this learning of drinking patterns, it may also be a matter of primary socialisation, when the child watches adult interactions in which alcohol consumption occurs (among other things), and/or secondary socialisation factors, where alcohol consumption is part of an interaction ritual chain (seeBrezovec, 2017). Thus, by considering the individual practice of alcohol consumption, the social foundations of this phenomenon are also considered. Individuals practise what they have learned in their own way – an individual drinks alcoholic beverages when it suits them. However, this is constantly related to values and normative foundations of drinking.

The abstraction and theoretical-methodological principle of this type seem logical and clear at first glance, but a deeper elaboration points to problems. They may manifest themselves in attempts to find out from the same individuals what alcohol consumption really means to them. An example can be found in Brezovec (2021). When interviewees in in-depth interviews were asked what alcohol consumption meant to them, they did not give specific answers, that is, they did not know how to directly answer the question about the meaning of alcohol consumption for them or their social life. Alcohol consumption is simply present for them, and its importance alone could not be defined. In this example, we can say that the (social) ethos of alcohol consumption does not exist in and of itself. It was only when we started to talk about the accompanying social phenomena and everyday life that the meaning of alcohol consumption for the individual, and thus for society, became clearer.

This brings us to one of the difficulties arising from the exclusive application of the principle of methodological individualism to the question of the relationship between society, the individual and alcohol consumption. The individual rationalisation of alcohol consumption is linked to other social forms of rationality. In other words, alcohol consumption is not an expression of sociability per se. It becomes a social phenomenon only when linked to other social phenomena and particular situations in which the action takes place. For example, the consumption of alcohol does not make social sense if disconnected from a social situation. A celebration does not take place because alcohol is consumed, but alcohol is consumed because there is a celebration. In this sense, the individual can be the basic unit of the sociological analysis of alcohol consumption, but only if the context in which the individual attaches social meaning to alcohol consumption is also considered. Alcohol consumption is a dependent variable related to other social phenomena or actions.

Moreover, alcohol consumption is highly dependent on the particular situation in which it takes place, which relates to the previous paragraph. It is a social phenomenon that changes. At one point, a certain amount, type, and manner of alcohol consumption may be acceptable, while at other times it is condemned. An individual involved in society has to “surf” the wave of social conventions and regulation of the phenomenon. A useful term that can describe this process of achieving the sociability of alcohol consumption is the one used as a foundation of ethnomethodology – the principle of indexicality. Indexicality is a phenomenon that describes the adaptation of actors to a particular context. Individuals form meanings based on their own knowledge of the situation and make them rational – common sense for themselves, but also for the society around them (see more inGarfinkel, 1965 inEisenmann and Lynch, 2021: 13). Here, then, we must pay particular attention to the contextual ambiguity of alcohol consumption in an individual's social life (if we are to understand the same phenomenon sociologically). In other words, the individual rationality of alcohol consumption is not stable, but depends on the nature of the situation in which it occurs. It is important to emphasise that this degree of disorder in the rational derivations of alcohol consumption does not negate methodological individualism, but somewhat complicates its application in the theoretical explanation of the social dimensions of alcohol. Indeed, by the circumstantiality of the phenomenon, we can speak of individual (socially constructed) motives for alcohol consumption, but these motives are too widely dispersed situationally. As such, they depend to a greater extent on the dimensions of knowledge within the individual's situation and their (internalised) rationality. The individual and their actions in the community are a product of the regularity of a given situation. In this respect, it is not the people (individuals) and their situations that are important, but the situations and their people (individuals). Not violent individuals, but violent situations (Collins, 2008:1).

Methodological Situationism as a Supplement to Individualism in Reflection on Alcohol Consumption

Methodological individualism can be a starting point for a socio-theoretical understanding of alcohol consumption. However, because of the difficulties already indicated, it requires certain supplementary approaches. In the previous section, the main drawback was related to the situational dimension expressed in the processes of alcohol consumption. Indeed, alcohol consumption as a social phenomenon varies according to the situation in which we find ourselves. If we focus primarily on the individual and the production of their rationality in relation to society (acting in the community), we cannot fully explain the social aspects of alcohol consumption theoretically. Therefore, the individual must be placed in the context of the situation in which they form the meaning of the social.

The term “situationism” appeared as early as the 1960s, mainly within the framework of psychology, as a kind of critique of the decontextualised approach to human behaviour (Bowers, 1973). Situationism in sociology, however, is most pronounced and most specifically defined in the work of Randall Collins (1981). Before we discuss it any further, it is also worth mentioning that his work and theory mostly reflect on Goffman’s Frame analysis. It is easy to see the connections between the approaches of Randall Collins (methodological situationism) and Goffman with his microstructuralism. In that sense, Goffman [1974] mentioned the primary frameworks. One of these frameworks is the social framework. What social framework does is something he calls “guided doing”, guiding the individual to the standards of their own doing (p. 22). Standards are something that will direct human action in a certain situation. So, in a way, Erving Goffman was one of the pioneers of methodological situationism in sociology, as he noted that the standard expression of the self, which is directed through the situational framework (social framework), is of great importance for sociology to study.

What both Goffman and then Collins did was to see that macrosociological phenomena can be understood through the rules and the ways a situation is realised. Since every situation contains structural elements, the broader structure is practically reduced to its most visible form – the form of interaction in the situation. Social situations are thus endowed with their own specific regularities in which the potential for the action of the individual and the group is organised. Thus, methodological situationism primarily considers the way in which individual phenomenological experience (psychological processes) is established in contextually-situationally organised activities, i.e., actions (Gobo, 2020: 20). At this point, it should be noted that Collins' considerations do not imply that a microsociological epistemology is more important or correct than a macrostructural one. Collins' reflections lean towards defining a theoretical-methodological tool that allows us to know both the interactive and the structural features. But, unlike methodological individualism, the basic unit for understanding the whole picture of society is not the individual, but the situation. The individuals are a part of the situation, but taken by themselves and with their expressions of meaning, they do not mean much. The situation presupposes their meaning – it regulates how one should interact with others (even if others are not physically present while the situation occurs).

As for the study of alcohol consumption, the situational determinants strongly emphasised by psychologists have been primarily related to alcoholism and the accompanying social pathologies which can occur in the context of consumption. For example, Buckner et al. (2008) examined the relationship between social anxiety and levels of alcohol use in specific situations. They concluded that individuals who experience some level of social anxiety in certain social situations are at risk of alcoholism (Buckner et al., 2008: 387). This alcoholism may be a result of tension in social situations, which alcohol can dissolve like a chemical compound. It is important to emphasise that while that study aims to answer certain questions of a psychological nature, it also has much to say about the field of sociology. Indeed, the study also raises questions for sociology and its theoretical explanations of alcohol consumption. While it confirmed the relationship between social anxiety and the risk of excessive alcohol consumption in certain situations, it failed to emphasise the importance of situational determinants and the interaction in which the pressure on the individual arises. The structure of the situation and the individual’s internalised knowledge of that situation offered alcohol consumption as a valued option for relaxation. Alcohol was also part of situational coping. An important limitation of the study is that, like many others, it focused only on excessive alcohol consumption and the risk of alcoholism. Thus, a problem-focused approach can also be seen here.

A study on the situational determinants of alcohol consumption, which also falls within the scope of sociology, was conducted in Norway by Nordaune et al. (2017). They investigated the work environment and how alcohol consumption begins at the workplace. They examined who initiated the consumption, as well as when and how alcohol was consumed. The interviews revealed that the most common triggers for alcohol consumption at work were employers at certain company gatherings (54%). This was followed by customers with whom one came into contact (27%), and in 19% of cases, alcohol consumption was initiated by colleagues, i.e., the work collective. The most common situations in which alcohol consumption occurred at work were celebrations by the work collective and business trips (Nordaune et al., 2017: 5).

While this study points to a lot about the situational determinants of alcohol consumption, it lacks theoretical determination, and its objective is almost just to present the situation without reaching a deeper understanding. Although the study started from situational elements, these were not sufficiently structured in terms of theory. So, the scope of the study was a description of what was manifestly undertaken through empiricism.

If we were to apply situationism in the consideration and understanding of alcohol consumption, we would still need to list some basic steps by which the same theoretical-methodological approach could assist in the realisation of empiricism, but also produce a deeper level of theoretical consideration (of the results obtained) after the realisation of the empirical part. Therefore, in line with Collins' work and the application of methodological situationism, we need to adopt some of the basic theoretical assumptions about the situation that Randall Collins (2004) uses in his work and then apply them to the social dimensions of alcohol consumption. When considering the situation, we must also pay attention to the interactional processes that occur within it. In that matter, Collins (2004) talks about interaction ritual chains that have their ingredients (co-presence, mutual focus of attention, exclusion of others, shared mood). The output of those rituals is certain aspects of social solidarity. So, in a way, the situation has led us to coordinate with others to achieve the feeling of social belonging. It is also important to note that this theory is rooted both in Emile Durkheim’s (1995) Elementary forms of religious life and Erving Goffman’s (1982) Interaction ritual. In order to keep alcohol consumption in the focus of the current paper, we cannot extend the basis of this theory, but we can see (further in the text) how well it can be implemented in explaining the phenomenon of (social) alcohol consumption.

In this sense, alcohol consumption is part of the formation of interactive ritual chains – through alcohol consumption, the ritual of a particular situation is co-actualised, laying a basis for developing situational solidarity with other participants. When we speak of the solidifying quality of alcohol consumption, we can speak of alcohol as deviant, but not as a deviant act. Depending on the culture in which we find ourselves, the consumption of alcohol or its prohibition promotes a certain community of knowledge on alcohol. However, if we look at the patterns prevalent in Western civilization, the knowledge of situational patterns makes alcohol a means of connecting with others. With this attitude towards alcohol consumption, we move away from an orientation towards the problem, and alcohol is determined within the meaning provided by society in a given situation, resulting in the creation of a certain kind of social solidarity.

But can social elements of alcohol consumption be completely subordinated to the situational framework? To some extent, it can be confirmed that alcohol consumption is part of the construction of an interactive ritual chain and solidarity within a given group of people. This is also evident in Krapina-Zagorje County, where mocking expressions about those who do not drink are common in situations where alcohol consumption is desired. Moreover, those who consume alcohol more frequently also have a higher sociability index (Brezovec, 2021: 182). Thus, while the situation determines the direction of the interaction, this does not mean that the individual is left completely alone in it. Even under the pressure of the situation, the individual shapes their own meaning of alcohol consumption according to their motives or experiences. The tailored framework for alcohol consumption is given, but the motives and, ultimately, action, vary according to the social roles, as well as the experiences, of those present. The amount of alcohol consumed also depends on the motives and experiences of the individuals: how and with whom one drinks alcohol, etc. Despite the great importance of the microstructural framework, the real meaning of this situationally permissible consumption enters the sphere of the individual realisation of the meaning of social life.

Therefore, alcohol consumption is situationally determined. There is social permissibility and even pressure to consume alcohol. But the significance of alcohol consumption for individuals taking part in this ritual establishment of interactive solidarity varies depending on their motives for participating in that same situation. It can be said that the situation reflects the social contract that the individual will later practise in their own way. In the field of interaction relations, the situation dictates the ways of permissible action, but it is up to the individual to manoeuvre that action in a way that is acceptable to them. It is important to add that we do not engage in psychologising social relations. If we look through a sociological-phenomenological prism of interaction during our lives, all the situational patterns we have experienced and adopted have shaped us as individuals. Based on these experiences, the now-formed social person enters each new situation with a certain impression of the world that they use to successfully overcome new challenges of social life. In that sense, reflexivity in interaction (seeCooley, 2010 [1902]: 88) is a social phenomenon. It is a kind of upgrade of the assumed social patterns. These patterns, through individual history, form a person, but in the end, the person also forms the course of these patterns – their eventual construction, deconstruction, destruction, and reconstruction.

Previously in the text, the emphasis was placed on the individual as a specific, internalised society. The situation has its regularities, but the individual also has their authenticity produced by the uniqueness of their social experiences. How they will interpret situational determinants and organise their actions will also depend on this accumulated experience. Such is the case with situational derivatives of alcohol consumption. Practising alcohol consumption, which is social, is subject to individual creations of meaning for specific situations that are imposed as defaults.

Methodological situationism can penetrate certain social elements of alcohol consumption. However, the achievement of cognition through the exclusive use of methodological situationism remains primarily at the level of structure (either micro- or later macrostructure), denying the individual and their ability to manipulate certain situations in which alcohol is consumed.

Two-stage Epistemological Model for a Sociological Theory of Alcohol Consumption

How to establish the conditions for developing a sociological theory of alcohol consumption? The construction of the theory cannot be divorced from reality (in this case), everyday manifestations of alcohol consumption in society, which takes place in the framework of social interaction. The reality of alcohol consumption in interaction does not concern alcoholism, but situational norms of consumption. Alcohol consumption in society results from what is called practical reasoning in ethnomethodology (Knorr-Cetina, 1981: 1). The practical reasoning of alcohol consumption is not oriented towards possible alcohol dependence. In other words, in social forms of alcohol consumption, a person is not concerned by possible alcohol dependence, but the best way to meet the expectations of a given situation (and others who participate in it) or their own hedonistic aspirations. Alcohol dependence in the context of social consumption is an exception rather than a rule. In this respect, sociology should also address the rule on alcohol consumption, and talk about the exception based on that rule. In other words, sociology cannot proceed with its episteme in explaining alcohol consumption by describing the phenomenon starting from the problem or determinant to the problem (having problematic drinking as the final target).

Having said all this, it is necessary to specify the epistemological assumptions of the sociological approach to alcohol consumption. Each of the concepts elaborated so far has certain shortcomings in relation to our phenomenon of investigation. However, in a kind of synthesis, the basic sociological starting points for approaching the phenomenon can be pointed out. What is certainly common to both epistemes is a kind of microsociological foundation. The first arguments made in this paper concern the social aetiology of alcohol consumption. Alcohol consumption occurs in society. This means that it manifests itself in a series of microsituations, that is, in a series of interactions. To start from action, from a microsituation, is to understand alcohol in its basic empirical manifestation. By starting from this phenomenon, it is possible to further understand the structural constructs associated with it. However, it is particularly important to stress that, in this way, the sociability of alcohol consumption is not set as an exclusively microsociological phenomenon. It is a phenomenon that is approached inductively – starting from action (understanding the microsociological determinants) and proceeding towards structure (the macrosociological). In this sense, alcohol consumption is only microsociological in its method and comprehensive in its epistemology (both micro- and macrosociologically oriented).

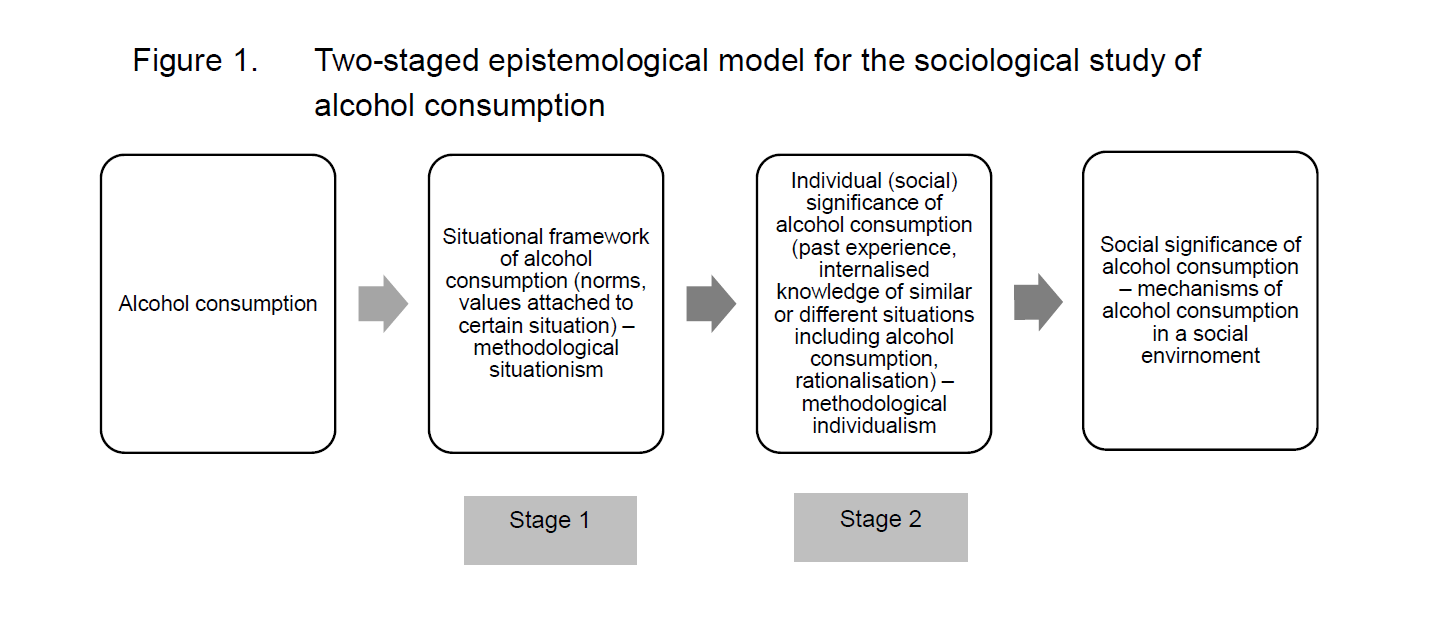

Although both methodological individualism and methodological situationism have relatively similar paradigmatic foundations, there are clear differences between these approaches. They differ in that situationism focuses on the situation and individualism focuses on the individual response to said situation. The situation focuses more on social regularities – values and norms that an individual must know in order to participate in society. Individualism accepts the sociability and regularity of the situation, but focuses on how individuals rationalise their own actions and those of others. It could be said that individualism is an extension of situationism. It has already been mentioned that an epistemological model is being developed for the study of alcohol consumption. It is two-tiered in its nature, given the approaches that have been elaborated. These approaches cannot be reduced to a single common denominator, but may become separate stages in understanding the sociability of alcohol consumption. Thus, before embarking on a sociological approach to alcohol consumption, it is necessary to consider the situational determinants of alcohol consumption in societies and, accordingly, to begin to analyse the individual forms of alcohol consumption or its meaning. In other words, one must first recognise the social rules and common knowledge about alcohol consumption and then see how this knowledge is internalised by the individual, shaping their unique actions. The authenticity of an individual's action relating to alcohol consumption is not theirs alone, but results from the sum of their experiences (of situations) with the general social meaning of alcohol consumption. To know the specific situational determinants of alcohol consumption is to know the basis for the development of individual rationality regarding the phenomenon of alcohol consumption. In this sense, the social precedes the individual, who in turn confirms, reconstructs or deconstructs the social (in our case, alcohol consumption). Here, of course, it is not yet possible to speak of a theory, but an epistemological model is suggested which, in conjunction with the empirical data so far, could provide a clearer definition for the development of theoretical concepts within the sociology of alcohol consumption (see Figure 1). But with this framework proposed by the author, there is a strong chance to get closer to understanding the social mechanisms behind alcohol consumption (excessive, problematic or normal).

Conclusion

The main objective of this paper has been to provide a basic paradigmatic and epistemological framework for developing a sociological theory of alcohol consumption. In doing so, it emphasises the rejection of the so-called problem-oriented approach within the sociological consideration of the phenomenon in order to capture the social dimensions of the consumption and meaning of alcohol rather than exclusively alcoholism or excessive drinking. Alcohol consumption is inextricably linked to society. Society gives alcohol its meaning and purpose. Alcohol consumption is part of social cohesion and, as such, should not be considered exclusively in the realm of alcoholism as a disease or social pathology. In this respect, the paper points to the importance of considering alcohol consumption within the framework of interpretive sociology or the sociology of everyday life (seeSpasić, 2004). The sociology of alcohol consumption ranges from the microlevel to explaining the macrostructural definitions of alcohol in society. However, within such a starting point, it was important to determine the basic theoretical-methodological principles which may guide the further construction of the theory of alcohol consumption as a social construct. In this sense, the synthesis of two microsociological ideas should be used to establish the theoretical and empirical foundations for the study of alcohol consumption: the principle of methodological individualism and the principle of methodological situationism. The theoretical argument in this paper proposes the synthesis of these two approaches in terms of a two-stage epistemological, sociological approach to alcohol consumption. Before beginning to analyse the relationship between society and alcohol consumption, the sociologist should look at the situational determination of alcohol consumption and then at the way individuals rationalise that situation – how they adapt and manipulate the given situation. In other words, the situation provides the framework and the way we consume alcohol on certain occasions, but an individual will draw true rationality from that framework – they will find a way to consume alcohol in the best possible way in a given situation. The first step in determining the sociological approach to alcohol consumption must therefore focus on considering the situational framework. When considering alcohol consumption, the sociologist addresses the way in which drinking occurs in particular situations (how much, when, in what way, and what drink is consumed on particular occasions). Within the sociology of drinking, the sociologist then looks at the interactions within the situational framework. We should reflect on what kind of rationality determines the individual's actions, and how does the individual rationalise the given situation based on their previous experiences. The methodological situation is followed by methodological individualism in the context of sociological approaches to alcohol consumption. Both epistemological dimensions are essential in determining the interactional and structural aspects of alcohol consumption and its place within the framework of social relations. However, reference has to be made to the title of this work – In Search of a Theory. Indeed, the search for the theoretical background of the sociology of alcohol consumption should begin with clear paradigmatic determinations for the study of alcohol within sociology. Thus, this paper cannot provide a clear-cut theory of alcohol consumption in societies, but it can provide theoretical-methodological guidelines that will enable the theoretical conceptualisation of future research. The approaches to empirical studies presented an approximate sociological interpretation and theory. Therefore, the synthesis of empirical and theoretical knowledge is achieved by rejecting the tendencies of abstract empiricism. Similarly, the sociology of alcohol consumption becomes more powerful through a clearer theoretical orientation within the framework of sociology itself. The sociology of alcohol consumption, paradigmatically regulated within the framework of general sociology, no longer has the quality of an auxiliary discipline in defining alcoholism and excessive drinking. It can be individualised by considering the social dimensions of drinking (its functionality and dysfunctionality either for a society or for an individual in that society).

Final Remarks

Having a unique sociological foundation does not mean that this knowledge becomes an end in itself, but within a structured discipline, it can provide a more concrete understanding of the relationship between the social world and alcohol, which may also benefit other disciplines dealing with alcohol consumption. The independence of sociological knowledge is the basis of the multidisciplinary approach. To speak of a multidisciplinary approach in which sociology does not recognise itself is not multidisciplinary in the full sense. Thus, the author does not intend to distinguish between the phenomena of other disciplines or to say that sociology is more important than other disciplines when it comes to alcohol studies. The intention was to provide an epistemological basis for positioning sociology as equally important as other disciplines for studying the phenomenon of alcohol consumption.

Nor was the author's intention to create a new field within sociology – new, special sociology (thus confining the phenomenon within a new cage of disciplinary boundaries). Therefore, the term “sociology of alcohol consumption” was not used to mark the beginning of a new sub-discipline, but to reference general sociology and its possibility to explain this phenomenon in terms of social manifestation.