INTRODUCTION

It has been known since Aristotle that, in addition to being physical, human being is also a spiritual, rational, and social being; that is, a being of the community (‘zoon politikon’). From his belonging to society comes his need for companionship and familiarity with others. For this familiarity to be without conflict and tension, in every society there is a certain organization of social life. Historically speaking, the aforementioned organization of social life differs greatly. Traditional societies were characterized by strong belonging to a particular community characterized by a relatively homogeneous culture, and the emphasized importance of traditional authorities such as family and church. On the other hand, modernity is characterized by belonging to a society characterized by cultural heterogeneity, the creation of impersonal and contractual ties, and authority based on law1. The characteristics of modern societies are the diversity of worldviews and value systems of individuals, the pluralism of political concepts and parties, the coexistence of diverse religious communities, and the multitude of opposing social, cultural, and economic interest groups2. In such circumstances, one cannot avoid discussing their interrelationships and the degree and peculiarities of tolerating the different.

Since tolerance is the central theme of this article, before the empirical analysis of tolerance in six European Mediterranean countries, the introductory part presents the definition, theoretical explanations, methods, and examples of tolerance research.

DEFINING TOLERANCE

Until the 16th century, the term tolerance mainly referred to the ability to endure physical discomfort3. It is only within the complex modern societies that the ideology of tolerance appears. Initial ideas were related to discussions about religious (Christian) tolerance4,5. Newer discussions about tolerance discuss tolerance as a moral virtue of an individual, and a political virtue of a liberal state3. More space is left for discussions about freedom of conscience and opinion following the maxim about the equality of all people in rights and freedoms. However, religions still have an important role in encouraging tolerance6.

The initial step of the scientific approach to tolerance is precisely defining the term, and bringing it into relation with other related terms. The word tolerance is derived from the Latin verb ‘tolerare’, which means to suffer or to bear. From a psychological point of view, tolerance means the ability to endure physical or mental pain, discomfort, stress, or negative environmental pressures and influences. In social psychology, social tolerance involves putting up with something or someone unpleasant, repulsive, different, or unacceptable. It is an attitude towards someone or something or a way of dealing with people, ideas, or things, which allows the equal existence of these people, ideas, or things. At the same time, tolerance towards people refers to tolerance for a number of their properties and characteristics - behaviour, habits, attitudes, beliefs, appearance, etc.6. In sociology, tolerance means the moral virtue of an individual and the political virtue of a liberal state. It is a way of behaving by which we allow others the freedom to express opinions with which we do not agree, and the right of others to live according to their principles, which are different from ours3. Tolerance is one of the ideals of a democratic and pluralistic society, but also a highly desirable virtue for every individual. Sociologists are particularly interested in the connection between globalization and tolerance. They believe that globalization encourages the need for more intense and extensive tolerance because it is based on the increased propagation of more intensive communication between people of different physical, psychological, and social characteristics6.

When talking about tolerance, it is important to mention some related terms. First, these are the concepts of prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination. Prejudice is a hostile or negative attitude towards members of a recognizable group of people, which is based solely on their membership in that group. A stereotype is a generalization about a group of people, by which the same characteristics are attributed to almost all members of that group, regardless of the actual variations between members. Discrimination is unjustified negative and harmful behaviour towards members of a group, just because of their belonging to that group7. A term that can also be linked to tolerance is prosocial behaviour. It is any act committed with the aim of benefiting another person7. Some laws established for prosocial behaviour apply to tolerance. For example, the expression of such behaviour is influenced by the mood of individuals. Individuals in a good mood are more inclined to prosocial behaviour. Prosocial behaviour and tolerance are also affected by emotions such as fear, which most often reduce tolerant and increases intolerant behaviour6. Moreover, it is useful to mention the concept of social distance. It is the degree of social separation, diversity, and distance between individuals, groups, or layers of society. Social distance indicates the degree of closeness that individuals are willing to achieve with the average member of a certain social group. Expressing social distance is an indirect way of measuring prejudice against certain national, ethnic, racial, religious, and other groups, and is also a measure of tolerance8. The term opposite to tolerance is intolerance. It relates to attitudes and behaviours that do not show tolerance towards differences. It can be expressed as racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, anti-Semitism, chauvinism, xenophobia, and religious discrimination6.

THEORETICAL EXPLANATIONS OF TOLERANCE

More precise theoretical explanations of tolerance were created at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. The following is a presentation of several theories that enable a better understanding of the presence of tolerance in contemporary society.

According to the theory of social identity9, social identity is as important to individuals as individual identity. An individual is naturally close, loyal, and generous towards the group to which he belongs in relation to groups to which he does not belong. Bias towards one's group refers to positive treatment and feelings towards that group, and negative treatment and feelings towards other outside groups. The explanation for this attitude towards other groups is in the process of competition. As soon as people are divided into groups, competition begins. Membership in one's group creates a desire to win in order to gain supremacy, and increase self-esteem. The maintenance of group boundaries is also influenced by certain social and cultural factors that can increase attachment to one's group and isolation from outside groups. With the increase in intragroup interdependence due to shared values and goals, the need to maintain clear boundaries towards other groups also increases10. For this research we put emphasis on the conflict theory presented by Hovland & Scars, which states that the reciprocal relationship between ingroup cohesion and outgroup hatred depends on the circumstances and most often takes place due to competition for physical resources and political power. A lack of resources in an inhabited area leads to conflict between two or more groups, which favours the creation of feelings of fear, insecurity, and threat, and, consequently, intolerance and hatred towards outside groups7. For example, when it comes to drug addiction the social conflict theory states that there are higher numbers of drug abusers in lower social classes and low income families. Drug abusers tend to turn to crime, or are perceived as criminals, and this leads to conflict with other social groups, and intolerance of their lifestyle in the society11. Furthermore, according to the scapegoat theory12, frustration caused by a real conflict results in aggression toward the so-called scapegoat. For example, an economic crisis and a sudden drop in standards in a country can bring about some unpopular groups being blamed. Thus, as a result of the economic crisis in Germany after the First World War, many turned against the Jews, and in the USA violence against Arabs increased after September 117. Blumer points out that in such cases, prejudices are the result of a change in collective perception, which is stimulated by the media, or the public characterization of some groups as negative13.

In modern societies characterized by the existence of many different groups to which an individual can belong at the same time (e.g., one by ethnic origin, another by religion), there is a higher probability of creating a context in which loyalty and attachment to one's group are not necessarily connected with hatred of outside groups14. Today, mixed marriages due to religion, race, language, and nationality are common. Lipset states that the differentiation of roles and the crossing of groups to which we belong is an important prerequisite for the development of stable democracies, and thus more tolerant societies15. This thesis is related to the concept of social capital, and the theory of socio-cultural development. Putnam states that social capital refers to the characteristics of social organizations such as trust, norms, and networks16. Fukuyama believes that social capital is manifested through the ability of people to cooperate to fulfil common goals17. In both cases, a tolerant society encourages communication between different groups. A society with high social capital is a society of intertwined ties, in which individuals can rely on others from their networks. A fundamental prerequisite for the creation of such societies is the growth of trust in society and the formation of civil society. It consists of groups and organizations of a formal or informal type, that act independently of the state and the market, and promote diverse social interests18. Such organizations connect people through networks, horizontally and vertically. Inglehart states that at a high level of economic development in modern societies, certain intergenerational changes occur, and the importance of personal freedom increases19. Economic prosperity frees people from the pressure caused by material problems, and restrictive norms are slowly replaced by more liberal principles. People focus on post-materialist values, and personal choice and individualism come to the fore. Societies focused on personal choices are more sensitive to discrimination and violations of human rights, and are guided by ideas of tolerance towards diversity, gender equality, and alternative lifestyles20.

RESEARCH ON TOLERANCE

Since tolerance is based on attitudes, its existence and strength within a population can be determined by measures of attitudes. To examine attitudes, researchers use specially created scales, which contain a series of questions aimed at a clearly defined object of attitude (e.g., attitude towards members of a certain nation). The answers to the questions determine the intensity of the attitude, which can vary from extremely negative to extremely positive. The scales can be used to examine ethnic prejudices; that is, the social distance that an individual wants to maintain in relations with members of another ethnic group. For example, people of one ethnic background can be asked about the degree of closeness they would be willing to have with members of another ethnic group (would they agree to live in the same country or neighbourhood, work in the same factory, be friends or marry, etc.). The assumption is that consent to greater closeness means greater acceptance of another ethnic group, or greater tolerance towards it, and vice versa6. Research on the levels of tolerance is mainly focused on specific countries due to their specific religious, political, and social context.

Loek Halman analysed variations in the level of tolerance in different European countries. His analysis was based on research conducted from 1988 onwards within the framework of the Eurobarometer and European Values Study project. The Eurobarometer survey21 showed that the majority of Europeans approve of the ideals of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and recognize and accept human diversity while condemning racist attitudes. However, most Europeans also believe that there are too many people of different races and nationalities living in their countries. Regarding this question, Europe can be divided into three parts. The first part consists of intolerant countries, in which there is a widespread opinion that there are too many people of different nationalities or races in their country (Belgium, Germany, France, and the UK). The second part are tolerant countries, which do not think that there are too many people of different nationalities and races in their countries (Ireland, Spain, and Portugal). The third part are the countries that are between these two extremes (Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark). Furthermore, the data of the research carried out in 1981 and 1990 within the European Values Study project, enables an answer to the question of whether intolerance is directed only at foreigners, or at other groups in society. When asked which groups they considered least desirable in the neighbourhood, Europeans cited those with problematic behaviours, such as alcoholics, drug addicts, and political extremists. Individuals with potentially problematic behaviours are less desirable in the neighbourhood than individuals who differ in terms of nationality, race, or religion. Also, regarding the tolerance towards strangers in the neighbourhood (e.g., people of different nationalities or races) the participants are intolerant if they believe that they disturb their lives22. However, since the end of the 1980s, certain social changes have taken place. Therefore, the stated results should be interpreted with some caution. Economic depression, and an additional influx of asylum seekers and economic immigrants, were recorded in European countries. Such circumstances potentially changed the degree of tolerance towards foreigners.

Recent studies of tolerance in Europe showed that the association between education and levels of trust and tolerance varies significantly across countries. A major source of this variation lies in the way in which individuals react to the level of diversity in the country where they live23. Kuyper showed that Europe is moving towards more tolerance and that the differences are related to other values, levels of income and income inequality, educational attainment, religious factors, degree of urbanization, EU membership, and political systems, etc.24 Stoeckel & Ceka showed that far-right groups (i.e., fascists and neo-Nazis), and Muslims were the most disliked groups in Europe25. Also, conspiratorial thinking and cosmopolitanism emerge as the most important predictors of political tolerance. Recent research often states that education makes modern societies more tolerable26,27. More specifically, it is important to teach children and young adults about social diversity, and conduct more research since the level of tolerance does not only relate to social context but also some individual differences28,29.

ANALYSIS OF TOLERANCE IN SIX EUROPEAN MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES

In this article, the results of the tolerance research obtained within the European Values Study project are used. It is a comparative international project in which the values of the inhabitants of European countries are examined. The data provide insight into the ideas, beliefs, preferences, attitudes, values, and opinions of citizens across Europe. It is a valuable source of data on how tolerant citizens in European countries are, or towards which social groups they show a greater or lower degree of tolerance. We focus on the analysis of tolerance in six European Mediterranean countries: Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania. The data obtained from research conducted in 2017 are used. The objectives are to determine for each of the mentioned countries: (1) the level of tolerance or intolerance towards social groups in general, (2) the level of tolerance or intolerance towards individual social groups, and (3) the existence of statistically significant differences between different socio-demographic groups of respondents concerning their level of tolerance or intolerance.

METHODOLOGY

The European Values Study project began in 1981 and is repeated every nine years in a changing number of European countries. In this article, the results of the tolerance scale obtained in 2017 on samples of citizens in Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania were analysed. As for the type of samples by individual countries, they are different, but they share the characteristics of being probabilistic and multiphasic. In terms of sample size, 9 001 respondents were included in all six countries, and their structure by individual country is as follows: Albania (16,1 %), Bosnia and Herzegovina (19,2 %), Croatia (16,5 %), Italy (25,2 %), Montenegro (11,1 %), and Slovenia (11,9 %).

As a measure of tolerance, or intolerance, towards certain groups, the respondents’ answers to the question of which of the nine social groups they would not like to have as neighbours were used. The question was in a dichotomous form in the questionnaire, where respondents could mark whether they wanted a certain social group for their neighbours. The responses of individual respondents were added together to create one quantitative variable that describes the tolerance of each respondent towards the idea of having certain social groups as their neighbours. The obtained variable was used for further statistical analyses that were made following the research objectives.

In the analysis, the Clopper-Pearson method was used to calculate the interval of proportions of citizens in certain countries concerning their desire not to have certain social groups as their neighbours. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the socio-demographic groups (gender, age, and level of education) of respondents concerning the previously described quantitative variable. These tests were used because the Kolmogorov Smirnov test indicated a non-normal distribution of the used quantitative variable (sig. = 0,000). The statistical program SPSS (v21) was used. The results were presented tabularly and graphically using box plots, and the option of obtaining a display in the form of folders was used in the Microsoft Office 365 program package. Conclusions about the results were made at a significance level of 5 %.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Level of Tolerance towards Social Groups in General in Different Countries

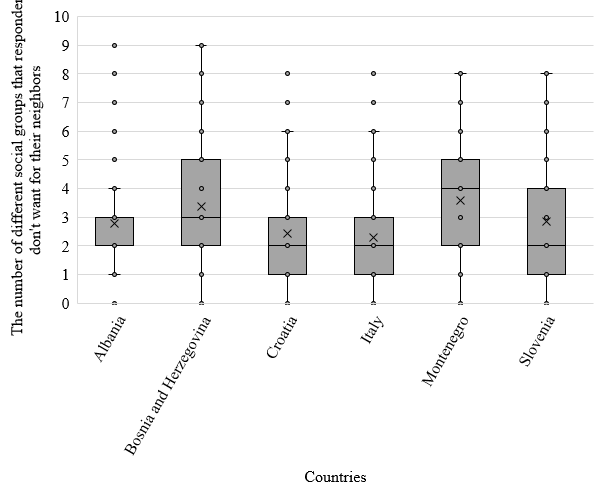

The first research objective was to determine the level of tolerance or intolerance in six European Mediterranean countries. To answer this objective, a question about which social groups were not desirable as neighbours was used for the analysis. More specifically, the respondents in the EVS survey were asked to choose which of these social groups they do not want as their neighbours: people of different races, heavy drinkers, immigrants/foreign workers, drug addicts, homosexuals, Christians, Muslims, Jews, and gypsies. Since the question of interest was asked in a dichotomous form, for each respondent, the points he achieved were added up concerning the number of groups that were not desirable to him. If a respondent chose all nine social groups as undesirable, he received the maximum number of points. Based on the described procedure, a new quantitative variable was created, the results of which were used to obtain a box plot representation of the points achieved by respondents from all six observed countries.

The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 1. Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia are the countries with the highest tolerance levels compared to the other countries. Respondents from these countries achieved the fewest points, the median value for them is two, while for the other countries the median values range between three and four. The lower the median value, the fewer social groups were identified as undesirable neighbours by respondents in the survey. Furthermore, the analysis pointed to the fact that the most remarkable differences in answers between respondents were found in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This information can be seen in the elongated form of the box plot, which points to the fact that there is a considerable percentage of respondents who do not want a single social group as their neighbours, but also a percentage of those who have no problems with any social group. In contrast, of all the six observed countries, Albania proved to be the most homogeneous, as the majority of respondents from that country do not want just two or three social groups as their neighbours.

Level of Tolerance towards Individual Social Groups in Different Countries

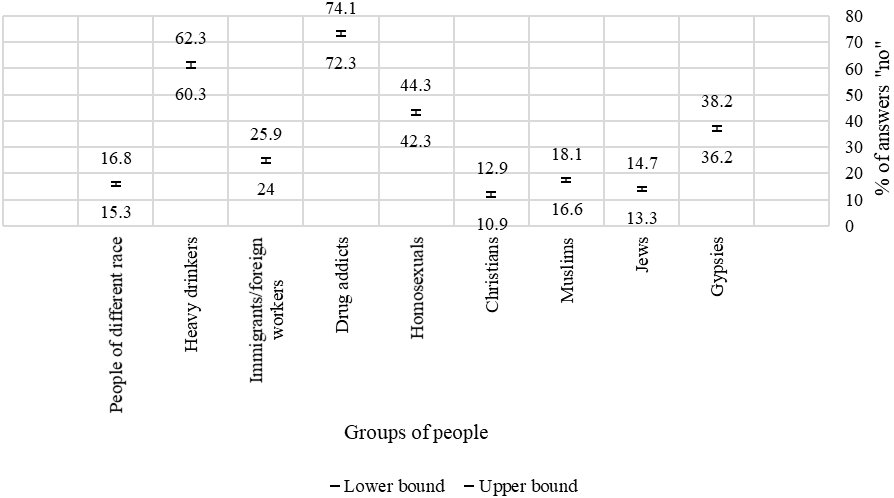

The second research objective was to determine the level of tolerance towards individual social groups in six European Mediterranean countries. The analysis showed which of the social groups are considered the most problematic in different countries. Using the Clopper-Pearson method, at a significance level of 5 %, we calculated the intervals of the proportions of respondents who chose certain social groups.

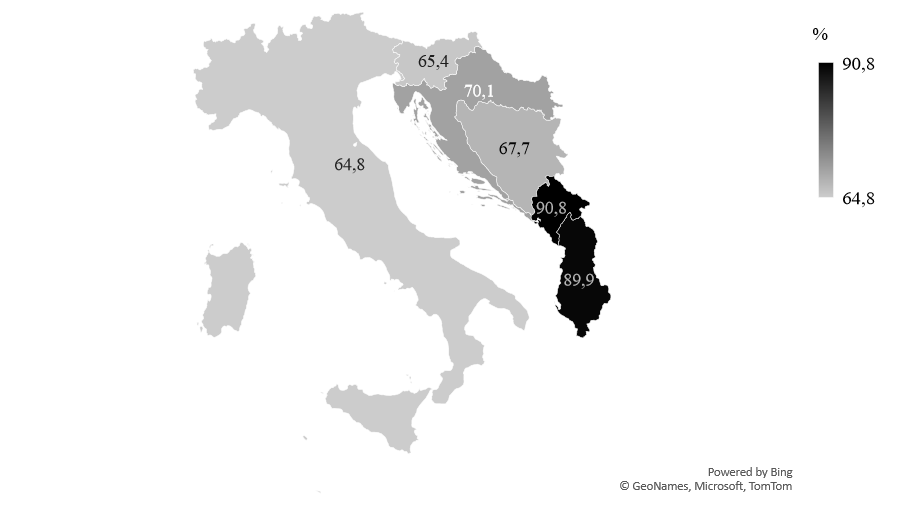

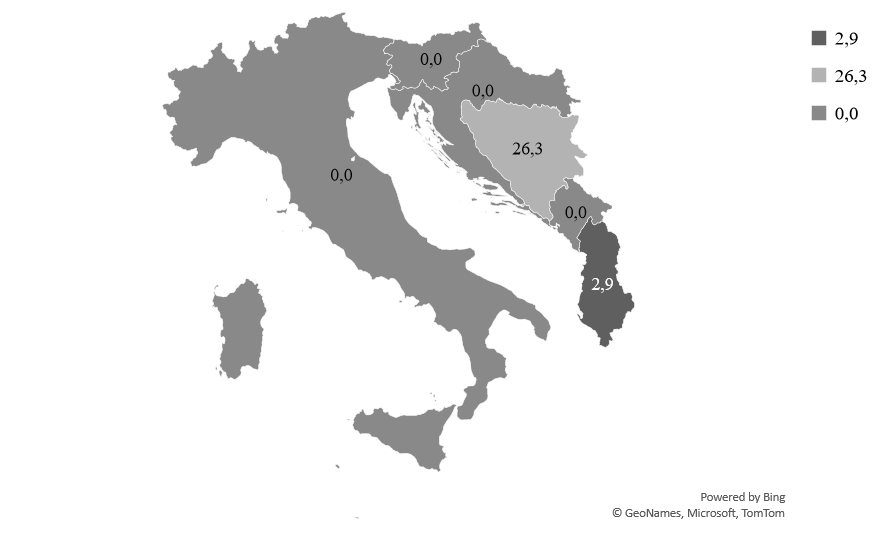

The results are shown in Figure 2. Members of the ‘drug addicts’ group are the most problematic - between 72,3 % and 74,1 % of all respondents in the survey do not want them as their neighbours. The social groups of the ‘heavy drinkers’ are also not desirable for approximately 60 % of all respondents. These two social groups can be considered as groups of people who are perceived as a threat to social and personal safety, due to their possible deviant and antisocial behaviour. This threat is often associated with the stigmatization of those groups in society. So, intolerance towards them in most cases exceeds the real threat they represent. Thus, the stigmatization of these groups, often due to a lack of knowledge and prejudices, results in their being perceived as a threat to social and personal security. Because of the threat to security, fear appears, which makes people less tolerant. They focus on their security, so terms such as civil liberties and human rights are less accessible in their memory [30]. On the other hand, approximately 10 % to 18 % of all respondents do not want members of different religious groups (Christians, Muslims, and Jews) and people of different races as their neighbours, making them the least problematic. The mentioned social groups can be considered as groups of people of different racial and cultural heritage. Tolerance towards these groups is not related to a threat to personal security, but to a threat to cultural heritage, and the preservation of national identity and tradition. It is related to the concept of sociotropic threat, which is defined as generalized anxiety and a sense of threat to society, the state, or the region in which one lives31. According to the results, the perception of such a threat was not a problem in the analysed countries.

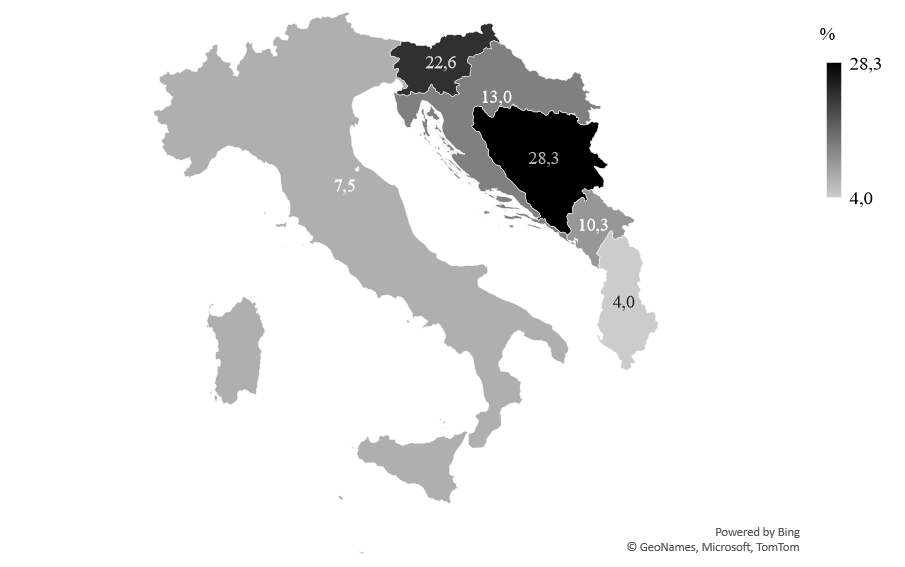

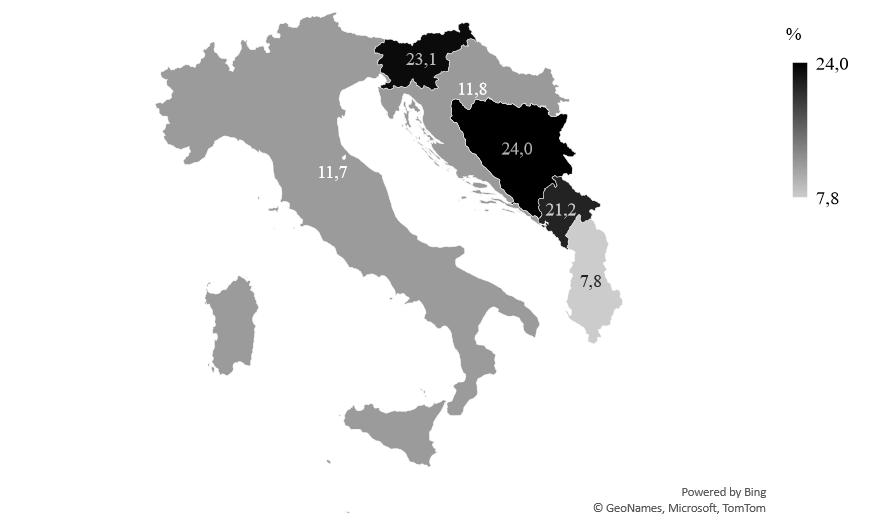

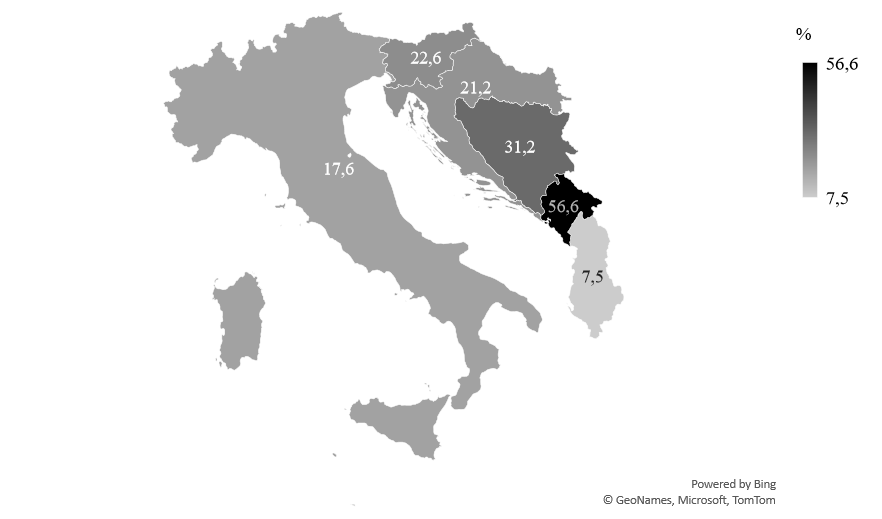

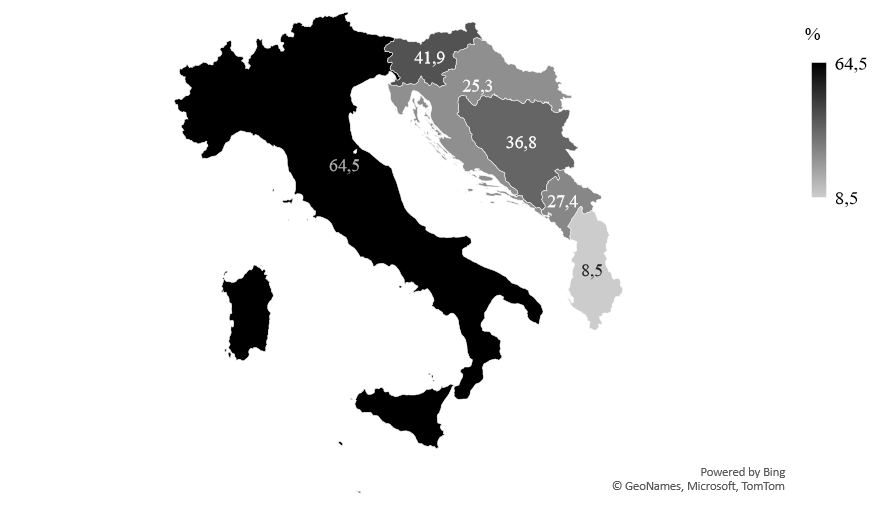

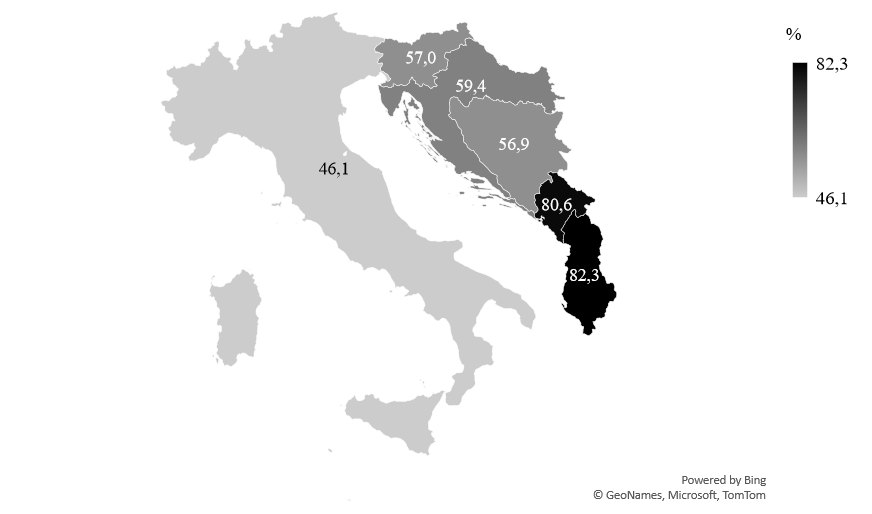

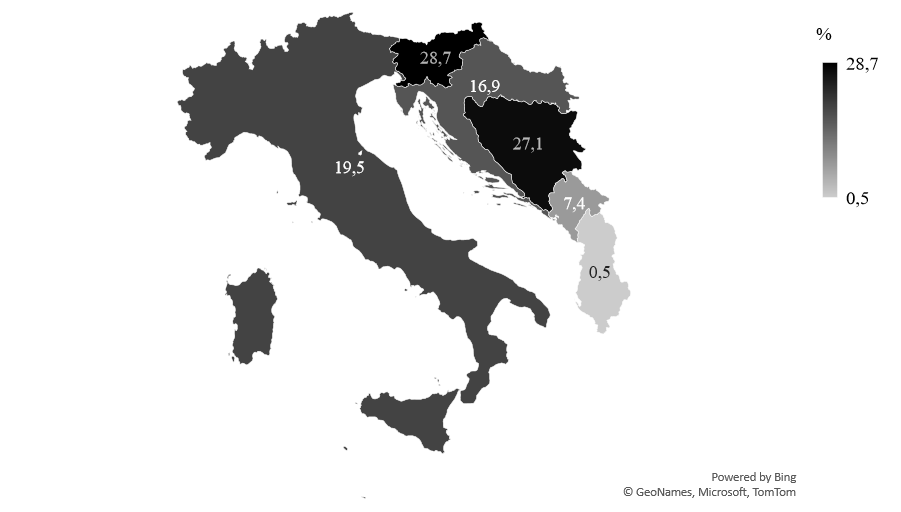

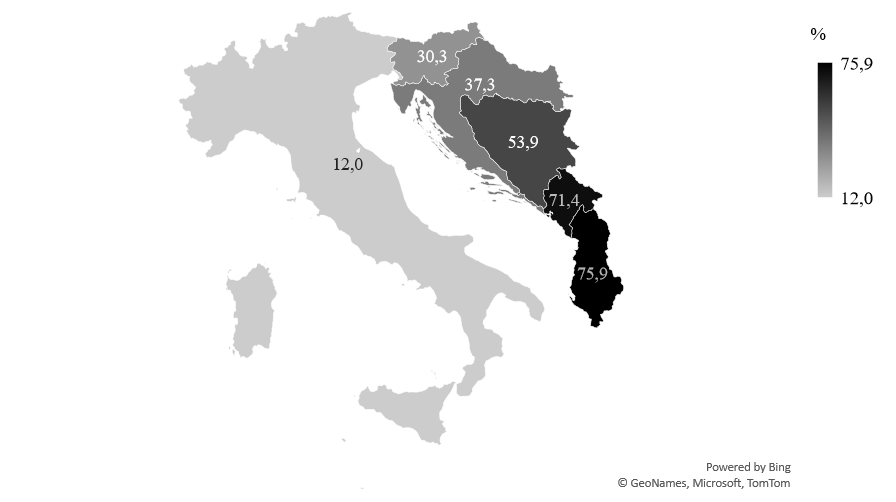

The results are also presented via the following Figures 3 to 11. They visually present which social groups are least desirable as neighbours in certain countries. People of different races are least desirable in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Slovenia (over 23 % of respondents agree with this statement). Immigrants and foreign workers are least desirable in Montenegro (56,6 % of respondents agree with this statement). Italy leads all countries in terms of the lack of desire to have Gypsies in their neighbourhood (64,5 % of respondents agree with this statement). Heavy drinkers and drug addicts are the least desirable in Albania and Montenegro (over 80 % of respondents agree with these statements). Also, drug addicts are the most undesirable social group for neighbours in all observed countries. As for religious groups, Christians and Jews are the least desirable in Bosnia and Herzegovina (over 26 % of respondents agree with these statements). Similarly, Muslims are least desirable in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in Slovenia (over 27 % of respondents agree with this statement). For Christians, it should also be emphasized that, as a religious group, they are considered the least problematic group in one's neighbourhood in all observed countries. Finally, regarding social groups whose members identify as homosexuals, they are the least desirable in Montenegro and Albania (over 71 % of respondents agree with this statement).

Level of Tolerance towards Certain Social Groups Concerning Socio demographic Characteristics of Respondents

The third research objective was to determine the existence of statistically significant differences between different socio-demographic groups of respondents in different countries concerning their level of tolerance or intolerance. The following characteristics of the respondents were observed: gender, level of education, and age group. In general, women, younger people, and people with higher education express more negative attitudes or greater prejudices towards social groups and the behaviours of these groups that have more traditional or more conventional attitudes and behaviours7.

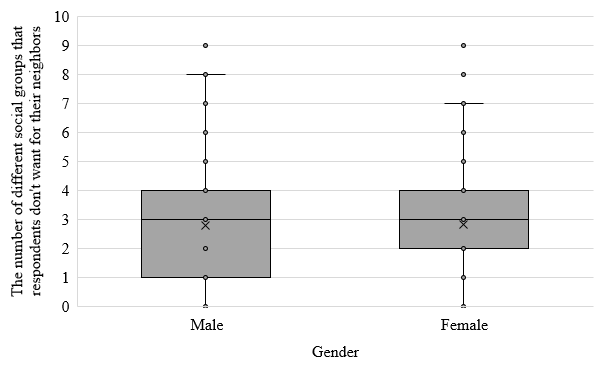

The results for the gender groups of respondents are shown in Figure 12 and Table 1. The number of social groups that men and women do not want as their neighbours is equal (Me = 3 for both), with slightly greater heterogeneity of results found for men. Using the Mann-Whitney test, the existence of a statistically significant difference (alpha = 5 %) between men and women in each of the observed countries was not found.

ANALYSIS OF TOLERANCE IN SIX EUROPEAN MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES

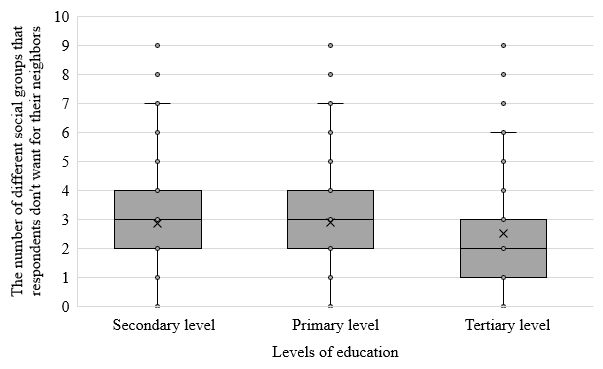

The results for the level of education group of respondents are shown in Figure 13 and Table 2. Respondents with a tertiary level of education have the fewest problems with different social groups (Me = 2), opposite to respondents with a lower level of education (Me = 3). To observe whether there is a statistically significant difference between respondents concerning the observed variable, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test. The analysis showed that the difference between groups of respondents with different levels of education, at the significance level of 5 %, exists among respondents from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, and Montenegro. More specifically, respondents with a tertiary level of education have lower mean rank values, which implies that they have chosen a smaller number of social groups that they do not want as neighbours, compared to respondents with lower levels of education.

ANALYSIS OF TOLERANCE IN SIX EUROPEAN MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES

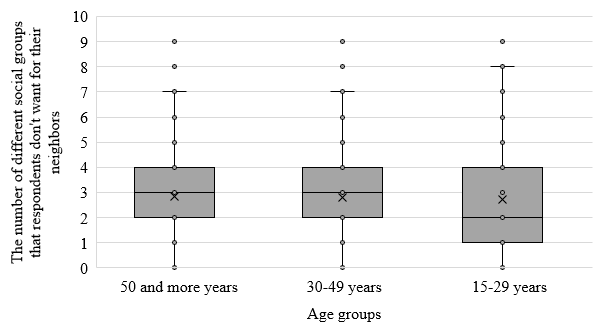

The results for the age group of respondents are shown in Figure 14 and Table 3. The younger respondents were more tolerant towards a larger number of social groups. Respondents between the ages of 15 and 29 mostly listed up to 2 social groups that they would not want as

ANALYSIS OF TOLERANCE IN SIX EUROPEAN MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES

their neighbours, while older groups of respondents listed up to 3 social groups. Also, Figure 14 shows that there is greater heterogeneity in the views of respondents on this issue among the younger age group. Since three age groups were compared and the condition of normality of the dependent variable was not met, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test. At the significance level of 5 %, there is a statistically significant difference between age groups in the following countries: Albania, Croatia, Italy, and Montenegro. In all the listed countries, except Croatia, younger age groups have lower mean rank values, which means that compared to older age groups, they marked fewer social groups that they do not want as their neighbours. In Croatia, those aged 50 and more years have the lowest mean rank value, which means that they have relatively more tolerance towards certain social groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this article is to present the level of tolerance or intolerance in six European Mediterranean countries. More specifically, using data from the European Values Study, we determined: (1) the level of tolerance or intolerance towards social groups in general, (2) the level of tolerance or intolerance towards individual social groups, and (3) the existence of statistically significant differences between different socio-demographic groups of respondents concerning their level of tolerance or intolerance. The results show that Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia are the countries with the highest tolerance levels compared to the other analysed countries. Also, members of the ‘drug addicts’ group, followed by the ‘heavy drinkers’, are considered the most problematic social groups in all six European Mediterranean countries. These results are in accordance with previous research, and also with the theoretical framework of social conflict theory presented by Hovland & Scars. ‘Drug addicts’ and ‘heavy drinkers’ are perceived as associated with crime and violence, and are as such not tolerated in the general population. When it comes to gender, there is little difference in tolerance level, while more educated, and younger respondents have higher levels of tolerance. It surely would be useful in future analysis to make a comparison of the level of tolerance in Central European countries and Mediterranean countries. Also, future analysis should include an investigation of more specific differences between respondents concerning their political orientations, and religiosity.

This article contributes to a better understanding of differences in tolerance levels in several European countries. In recent years, Europe is changing its social structure, so the examination of tolerance is important because intolerance increases conflict. It is also important to state that the increase in positive social relations is mainly influenced by social processes in which positive social behaviour towards stigmatized groups is promoted at all levels. This is particularly achieved through education, and media information32. It is necessary to systematically work on educating and informing citizens about the characteristics of different social groups, to reduce the perception that they are a threat, encourage citizens to be more tolerant towards them, and thereby build a more humane society.