Fr. Silvije Grubišić, the Neglected Bible Translator: Notes on Some Translation and Translational Solutions

1. Croatian Bible Translation

The history of Croatian Bible translation heritage is so rich that we should be somewhat embarrassed concerning how relatively little work we have done in careful and academic research and disclosures of this Bible translation wealth. With its historical, lingual, and linguistic treasury, especially in the dialectal history of translation and all its language varieties, Croatian Bible translation is, without any false modesty, at the very top of the European history of Bible translation traditions. Only a handful of European nations can boast of such Bible translations in the history of their dialectal idioms and their varieties as Croatian Bible translation can. Since the heritage of Croatian Bible translations is so plentiful, it would be wise to share a brief remark regarding the difference between lingual and linguistic terms, which refer to notions such as language, supradialect, and dialect. For example, until recently, the Kajkavian and Chakavian were considered dialects or supradialects in the Croatian language corpus, where supradialect is the higher category. However, in the last few years, Croatian Kajkavian and Croatian Chakavian have been recognized internationally as languages and are no longer supradialects.1

Speaking about Fr. Silvije Grubišić as a Croatian Bible translator and his Bible translations, we should, at least in outline, mention Bible translation in general. Bible translation is a complex and challenging task that contains methodological, linguistic, stylistic, and religious matters. It resembles a pendulum with three points of reference. In the translation process, this pendulum keeps “swinging” between three reference points – the source text, the translator, and the reader, hoping to create harmony among them. Concerning this, Božo Lujić aptly concludes that when Bible translations and translating are discussed, “The result is different types of translation: closer or farther from the original text, closer or farther from the reader” (Lujić 2018, 58).

From the perspective of method and language, there are different categories of Bible translations. According to their method, some translations are called word-for-word translations (philological or literal), and some we call free translations (or paraphrases). Also, there are adaptations, informal “translations” that are descriptive and whose primary goal is communication. However, these latter texts are in danger of being oversimplified in translation to the point of missing all the complexity in the crucial elements of the biblical original.2

From the perspective of the original biblical language, a translation can be considered standard, which means that it linguistically relies on the received standard language of the translator. However, more and more of the so-called contemporary translations aim to adapt to the reading audience and, occasionally, to the conversational language, which, of course, does not have to be identical to the standard language. Also, some translations try to enrich the sacral authenticity of the Bible as the Word of God through archaisms (most often in verb formation) or biblicisms (most often on the level of nouns) and even embellish the translated text.3

1.1. Who is Silvije Grubišić?

Fr. Silvije Silvestar Grubišić was a Herzegovian Franciscan, born on April 8, 1910, in the poor Herzegovian town of Sovići (in Bobanova Draga, between Grude and Posušje). He spent most of his life serving in Croatian missions in North America and among American Croats. He died in West Allis, Wisconsin, on May 12, 1985.

After finishing Primary School in Sovići, he graduated from a classical gymnasium in Široki Brijeg (1932). He joined the Franciscan order while still in a gymnasium (1929) and was ordained as a priest on June 16, 1935, in Mostar. He served as a Friar in Široki Brijeg until 1937, when Croatian Missions in North America asked for help in their ministry among American Croats. So, as a 28-year-old, Grubišić moved to North America (in 1938), where he spent the rest of his life in different American cities.4

Upon coming to the United States of America in 1938, Grubišić was appointed parson in the Croatian St. Mary’s Assumption Parish in Steelton, Pennsylvania. He served there for three years (until 1940). Next, he moved to Chicago and later to New York. He also served in many other American Croatian parishes in Milwaukee, Ambridge, and Florida and spent a year serving in Canada (1969–1970). In 1954, Grubišić led a small delegation of Croatian priests to the United States of America to see American President Eisenhower. The reason for the meeting with the President was to deliver a memorandum in which many (143) Croatian priests who lived and served outside Croatia asked the Yugoslavian authorities to stop persecuting believers.5

Grubišić’s Bible translation work and endeavor began in 1973 in Chicago and continued until 1984, a year before his death in West Allis, Wisconsin, in 1985. Unfortunately, his translation work or possible analysis of his translation in his homeland does not draw much attention.6 At the same time, his commitment to Bible translation was a cause of much writing in the United States of America, not only in their Croatian publications but in the American press.7

In his doctoral work ( Pastoral-theological and Catechetical Contribution of Bonaventura Duda to the Croatian Theology, 2013), Antun Volenik mentions Silvije Grubišić and his contribution to Bible translation in several places. Describing travels and pilgrimages of Bonaventura Duda, Volenik also mentions his visit to the United States of America in 1965 and his meeting with Fr. Grubišić:

In New York, he meets the Herzegovian Friar Silvije Grubišić, who served there as a parson. By then, he had already translated the Bible into Croatian “as a proper amateur, but of a high style” (Klarić, 9). A part of that translation, namely the Pentateuch, was later chosen by Duda as the template in the translation of the Zagreb Bible because of “the vigor of the language and because it, as such, represented a contribution to the contact of the Croatian Bible with the Anglo-American speaking and biblical-theological area” (Volenik 2013, 46–47).

Volenik further mentions some Bible translations and translators, Silvije Grubišić among them, who played a crucial role in the preparation and creation of the so-called Zagreb Bible: “Immediately before Zagreb Bible was published in 1967, we saw a publication of the translation by Ljudevit Rupčić which, together with translations done by Silvije Grubišić and Gracijan Raspudić, demand a special review since they will serve as templates for parts of the Zagreb Bible” (Volenik 2013, 159).

Grubišić was indeed self-taught in the Hebrew language, as he testifies (Grubišić 1979, 183). Still, Marko Mišerda, describing Grubišić as a self-taught biblicist and Bible translator, concludes: “It is interesting that Grubišić did not go through specialist Bible schools, but his enterprise overcame all difficulties” (Mišerda 1985, 99).

1.2. Types of Translation

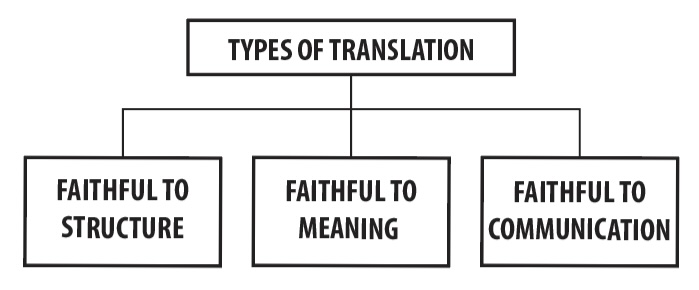

Instead of traditional categories and categorizations of Bible translations (philological, literal word for word, paraphrases, adaptation, etc.), it would be clearer to divide Bible translations according to types of translation as suggested by Heidemarie Salevsky (Lujić 2018). She argues that, in addition to traditional categorizations of Bible translations, we should accept a different model, which would use types of translation instead of categories of translation, namely three different types of Bible translation – concerning structure, meaning, and communication. It would look something like this, depending on which aspect the translation emphasizes (Lujić 2018, 59):

The ideal type of translation would be one that completely encompasses all three aspects. However, such typological representation of translations should not at all mean that one type excludes the other or that these types cannot overlap. Most frequent misunderstandings and disputes arise when, directly or indirectly, one attaches exclusivity to a specific biblical (type of) translation.

1.3. Biblical Translation of Silvije Grubišić

How does Silvije Grubišić’s translation stand in relation to the represented translation types? Which aspect do the particularities of his translation point to? Are his peculiar translational and lexical solutions the reason why Fr. Silvije Grubišić’s name is rarely, if ever, mentioned in popular media and expert circles of Croatian Bible translations and translators? For example, in the general introduction to the Bible (published by Kršćanska sadašnjost), in the description of the Book of Job, editors wrote: “We have used the manuscript translation of Silvije Grubišić here and there.”8

Grubišić’s translation of the Old Testament, some of his linguistic and translational solutions, and his complete approach to Bible translation most certainly deserve more attention than a casual note would imply. There are no indicators of exclusivity or universality in Grubišić’s translation. However, we can readily observe that his translation is remarkable in many respects. Among many Croatian Bible translations, it stands out as creative and unconventional in some elements but undoubtedly “faithful to communication.” Specificities of Grubišić’s translation are primarily seen in his vocabulary and lexicon. The language of his translation is very immediate and vivid, intensely direct, and sometimes bordering on ruthless cynicism. In his translation, Grubišić not infrequently uses dysphemism ( drop dead, butchered, dung, hussy, and the like) or colloquial terms ( pillowcase, bed, mischief, robber, mean, do-gooder, the poor, topple, and the like).

The translation does not contain unnecessary biblicisms, which makes it different from most other Croatian Bible translations. This fact alone makes the text come alive and closer to the average reader in a unique way, although it sometimes sticks out through inspirational, occasionally even provocative solutions, so direct that they border on colloquial mercilessness, causticity, and dysphemism. In all this, Grubišić tenaciously follows and conforms to the source text, as evident in some of his exceptionally valuable footnotes. Grubišić’s translation is not only vividly rendered, as might be done by another skillful linguist, but primarily well thought-through and exhaustively researched, not only from a linguistic and textual angle but also from a historical and religious context of the Bible. This is especially evident in Grubišić’s footnotes.

2. Vivid Translation

What made Fr. Grubišić embark on this monumental task and begin translating the Old Testament? In Grubišić’s own words, he set about this work prompted by the following ruminations:

I could not fathom such frequent publications of the New Testament without the Old. It seemed like cutting down a healthy and sound tree in bloom. Even if planted in the best soil, can the cut-off part ripen and yield the best fruit? That is when I got my hands on the Hebrew Bible. With all its scientific apparatus, it contains a bit more than 1400 pages. I got myself several grammar books and dictionaries. The ministry I was later posted to do required that I spend most of my time in my room. I had to occupy myself with something. Therefore, I set about translating the Old Testament. First, I started with the Book of Job. It is considered to be the hardest. If I persevere to the end, I say, the others will be easier (Grubišić 1979, 183).

We have already said something about the vocabulary and lexicon of Grubišić’s translation – it is not only vivid and unconventional but perhaps to some readers even inappropriate and improper, as seen in words such as rogues, good-for-nothings, scoundrels, forest robbers, do-gooder, stiffs, butchered, dung, drop dead, “šumetina” (augmentative for forest), “jametina” (augmentative for pit), and similar. Grubišić’s vocabulary is exceptionally close to the source text, which, when it was made, did not “suffer” from biblicisms in any form. The translator here dared to become close to the reader on the level of vocabulary and context, as we have already pointed out.9 In his translation, Grubišić crosses the lines of the sometimes trivial or clichéd biblical style.

However, it should be said that Croatian Bible translations keep sailing between Scylla and Charybdis: between faithfulness to the original, protecting the exalted and godly nature of the text on one side, and communicativeness and contextuality of the modern reader on the other. Whether we call it a balancing act or a compromise, it is the inevitable reality of Bible translation and interpretation.

Grubišić’s translation seeks to bridge the mentioned compromises or “balancing acts.” In that regard, we could say that the translation is successful in many elements. His lexicon, language, and style are, in many aspects, closer to the reader than most “predictable” translations and translational solutions.

For a better and more precise insight into all the distinctive features and values of Grubišić’s translations, let us consider several texts that showcase his translational solutions and skills. In his translation of the Psalms, we find many poignant examples of such solutions. Furthermore, much of his translational lexicon and vocabulary rigorously relies on the original Hebrew text, as we shall try to show in some of his translational solutions.

2.1. My Liver Jumps (Ps 16)

In the source text, the psalmist’s abdominal organs, primarily kidneys, and liver participate in his joy (16:7, 9).10 For reasons of style and comprehension, most translators here, as in some other places, instead of kidneys, as it is said in the original, translate this word as the heart. Šarić here states: “I always have the Lord before me. He is at my right hand, and that is why I never stumble. My heart rejoices, and my spirit ( liver) is glad, and my body rests in safety” (16:8-9). Consistent with the original and his translational uniformity, without stylistic subtlety, Grubišić translates these lines as follows: “I constantly hold the Lord before me, and from his right hand, I will certainly not depart. Therefore my heart rejoices, my liver jumps for joy, my body rests comfortably” (16:8-9).

Kidney or liver could, and should, be translated as conscience. Such is Alter’s translation (2007, 46), “I shall bless the Lord Who gave me counsel through the nights that my conscience would lash me.” In the original biblical text, the kidney (kidneys) represent a paradigm and metaphor for the center of man’s conscience. This is well illustrated in a text from the prophet Jeremiah where the people are described as those who are doing well (have taken root, bear fruit) but care little for their God. The translations of Kršćanska sadašnjost and Ivan Evanđelist Šarić here state, “You have planted them, and they have taken root; they grow and bear fruit. But you are only close to their lips, but far from their hearts” (רחוק מכליותיהם) (Jer 12:2).11

In many places, the heart, even when the original does not say heart, is a deft and subtle stylistic solution. Abdominal organs in the original biblical text far surpass only one organ, the heart, and this should be manifest in the translation.

2.2. Look at the Do-Gooder (Ps 37)

“Progress and prosperity are guaranteed for the one who is honest and upright” (Ps 37:37), Kršćanska sadašnjost translates: “Look at the upright and look at the blameless: the peacemaker has posterity.” Šarić renders this very similarly, “Look at the honest and look at the upright because he who is a peacemaker has a future!” (Ps 37:37). Grubišić’s translation is ingenious and lucid: “Look at the do-gooder, look at the straight shooter! A blameless man has a future.”12 In many places in the original, one must bear in mind a certain synonymy of the following notions: ישר ( honest, upright) and תם ( whole, of integrity). Many Croatian translations render this as upright and blameless, which are biblicisms of a sort. Grubišić persistently avoids biblicisms, choosing colloquial expressions, such as we find here in the do-gooder and the straight shooter. In every case, Grubišić tries to stay faithful to the meaning and structure, but he prioritizes faithfulness to communication.

2.3. Drop Dead (Ps 55)

The originality and the fierceness of Grubišić’s translational solution are especially highlighted in Psalm 55. Using melodramatic vocabulary, the translator here portrays the situation as somewhat grotesque. The narrative of the psalm focuses on the fact that the psalmist has been abandoned by his best friends, who have turned into enemies and are now trying to kill him: “You, my companion and I, my companion, my bosom friend!... You, whose company I was so fond of, with whom I have walked around in God’s house side by side! May you drop dead! May you fall into Sheol alive!” (55:16).

Using elements of imprecatory psalms, the psalmist wishes these to die. For his biblical text, Grubišić uses a very rough, somewhat raw, and uncouth term – (may they) drop dead. Why does Grubišić use this dysphemism here?13 When we consider the Hebrew original of this verse, we find יַשִּׁימָוֶת( yaššimāwet), which is a compound of נשא (“outsmart”) and מות (“death”).14 However, it is not entirely clear why Grubišić uses such a dysphemism ( drop dead).

2.4. My Brain Became Leavened (Ps 73)

Psalm 73 is, in many ways, exceptional and deserving of our attention. Especially, and because, Grubišić, in his translational inventiveness, adds additional emotional charge to this psalm. Brueggemann believes that Psalm 73 holds a “central place in the Psalter” (2007, 204). Artur Weiser comes to similar conclusions and says that Psalm 73 “holds the most prominent place among the mature fruit of the struggle and the pain the Old Testament faith had to endure. That is a strong testimony of the human soul’s struggle and could be compared to the Book of Job” (1962, 507).

Several psalms follow the orientation/disorientation/reorientation pattern. So, the psalmist is initially secure in his faith and trust in God and firmly oriented. Then, confused by wrongdoings and threats, distressed and disappointed in God and his (in)justice, he finds himself in a state of complete disorientation. He cannot understand the injustice God seems to allow: “I tried to understand all this, but it troubled me deeply” (Ps 73:16). This process culminates in the psalmist’s meditation and introspection when in the renewed presence of God (“till I entered the sanctuary of God,” cf. Ps 73:17), he observes the final destiny of evildoers and the wicked (“I understood their final destiny,” 73:17b). Psalmist has now been reoriented.15

Psalm 73 is typical of precisely these psalms, in which we notice the pattern of orientation-disorientation-reorientation. These psalms abound in very immediate vocabulary and lexis. Forms and formulas of poetic idyll are often avoided. Such intensive wording of the original asks for a reciprocal response from the translator. For instance, while in Psalm 73:12 a great majority of translators speak of thieves and deceivers, or sinners amassing wealth, Grubišić uses the language and vocabulary of the people and calls them scoundrels: “ scoundrels increase their wealth” (73:12).

In the next verse, the psalmist asks: “Have I, then, in vain kept my heart pure” (73:13; Kršćanska sadašnjost and Šarić), while Grubišić here, more intensely, and with a dose of cynicism, translates, “So (I) have kept my heart pure for nothing.”

And while the psalmist looks at the prosperity of the wicked (Grubišić: of the scoundrels), not understanding all these injustices, he becomes caught off guard, confused, and disoriented. He simply cannot understand all that is going on around him (73:21). His mind cannot fathom all these wrongdoings, so he concludes, “my soul was distressed” (Kršćanska sadašnjost) (73:21).16 And yet again, we are then surprised by Grubišić’s original, unexpected, and unusual translation of this verse which reads, “When my brain became leavened, and my emotions became hidden, I became a madman without understanding.” The original here compares and uses metaphors from the cottage industry. Such vocabulary points to yeast and fermentation (חמץ) in bread-making.17

3. Grubišić’s Footnotes

Besides everything that has already been said about Grubišić’s translational solutions, it is essential to say something about the exceptional value of his footnotes. These notes are not only very informative and concise but brilliantly educational and, in some details, acutely illustrative.

3.1. Psalm 1:1 What Luck

Grubišić’s vividness can be seen both in his translational solutions and footnotes. Stylistically, he is characterized by a conversational style. So, for example, Ps 1 in Grubišić’s translation says: “What luck for the man who does not come to the counsel of the wicked, does not participate in the assembly of sinners nor sits in the meeting of the ungodly.” All other translations render this as “Blessed is the man.” It is impressive how skillfully and knowingly Grubišić uses his footnotes. Merely by reading these concise translator’s notes, the reader will be schooled and educated. For example, in a footnote about the mentioned Psalm, Grubišić discusses different approaches and aspects of biblical translation and some concrete translational solutions from the cited text in the Psalter. In this footnote, we are once again met with his picturesque and somewhat lively conversational style and expression:

1:1 It is conspicuous to differ from other translators. The readers will at least ask themselves: Why this? – Translation from one language to another, as with many other things, depends on the taste. One translator can be more appreciative of the faithfulness to the source text, while another can be more enthused by the expressions of the language he is translating from. Personally, we hold that staying faithful is more important, especially if the original thought can be stylistically well expressed through faithful translation. So, good. The first word of the first psalm is translated as: Blessed! We find the same thing in other languages, although Hebrew uses a noun: ašre. We think that ašre is well expressed in Croatian if translated as a noun, as we have done. At the same time, the translation is faithful to the original. We will also try to proceed according to this rule in other places. That is what we do in the second verse. Instead of the customary expression: does not follow the counsel, we translate asah as holding council. According to the dictionary, that is one of its meanings, and it is more in the spirit of the Hebrew language, whose characteristic is the tangibility of expression. Language experts justify translating derek as assembly instead of the old way.

With relatively few words, Grubišić in this footnote provides a concise language analysis and translational aspects and variants. Also, he does not leave unexplained terms that he uses in his translation, which are perhaps not entirely clear, as will be seen in the coming example from Psalm 2. In his notes, Grubišić will explain why he sometimes uses terms that are most probably unfamiliar or unclear to a broader reading audience.

3.2. Psalm 2:3 “Gužve”18

The episode we find in Psalm 2 portrays different situations that Israel, this small nation overwhelmed by many superpowers of that time that wanted to enslave and eradicate them, found itself in. The psalmist points to the power of their God, so he sees their rebellions as folly: “Why do the nations rebel and the peoples plot foolish plans? Earthly rulers gather together, and princes deliberate among themselves against the Lord and his Anointed.” On the other hand, the Israelites decide: “Let us tear off their shackles ( moser, מוסר) and throw off their yoke” (Ps 2:2-3).

Grubišić here renders: “Why do earthly kings entrench themselves, and princes plot against the Lord and his anointed? Let us break their cords, shake off their yoke!” Grubišić expertly and meticulously expounds on the term cords and provides instruction for the reader:

2:3 Chains, shackles, and cuffs are words that presume some variety of metal or irons. However, at the time this psalm was written, in 10th c. BC, iron was most probably still a rarity. It was the Philistines who had a monopoly over iron in Palestine. Therefore mosarot must denote cords. Furthermore, they were easy to acquire: they were made of branches. Chastetree wood, willow wood, vines, and white vines were perfect for cords.

This kind of footnote will concisely and vividly teach the reader about the biblical text and the context of the time.19

3.3. 1 Samuel 10:11 and Pentecostals

Grubišić’s footnote on the text in 1 Samuel 10:11, describing an unusual event from King Saul’s life, proves even more inspirational. The King encounters a group of prophets in a “prophetic ecstasy.”20 Meeting this charismatic group, Saul himself begins to prophesy, so the text says: “All who knew him from before and have now seen him in a prophetic ecstasy among prophets, asked one another: ‘What happened to the son of Kish? Is he also among the prophets?’” Grubišić uses the footnote under 10:5 to describe the mission and the task the prophets of Saul’s time were to perform and says:

Here we encounter for the first time a significant phenomenon in the life of Old Testament believers: the appearance of the nabiim prophets… it is said that the first group was started by Samuel himself to confront the indolent priesthood. Its task was to proclaim the will of God. When proclaiming it, the prophets often fell into a religious ecstasy similar to today’s Pentecostals.

Things can hardly get any more illustrative or vivid. Here, again, Grubišić remains faithful to communication ( faithful to communication), gives particular care to structure, and especially lexicon ( faithful to structure), and finally, very carefully attempts to bridge the Old Testament world with our modern world, history, and culture. This can be seen in his footnote on the text of 1 Samuel 10:11.

Conclusion

In biblical translation, in the conception of translations according to their type ( faithful to structure, faithful to the meaning, and faithful to communication), Grubišić’s translation is more than exemplary in terms of satisfying the conditions of communication and meaning. In contrast, in terms of structure, it mostly follows other translations.

He certainly dove into translation and translating of the Bible, honoring and accepting the mentioned approach about three types of biblical translations. We have indicated and demonstrated that he desired to stay faithful to the original. Methodologically, though, he sometimes veered toward the word-for-word translation. However, this was not done mechanically because his translational vocabulary and lexicon clearly show that Grubišić wants to remain faithful to communication and not only the original.

For a more reliable idea, evaluation, and authentic fabric of Grubišić’s translation and everything that he lived through and experienced in the history of the Bible, as well as the historical background, the interested reader should, by all means, read his travelogue Pripovijest o Bibliji: S puta po biblijskim zemljama (1979). Grubišić embarked on his month-long journey to the Holy Land in May 1966. In this travelogue and the way he wrote it, a careful reader will not miss connections to his translation of the Old Testament.

Fr. Silvije Grubišić most certainly deserves more academic and general attention in the treatment of his translations and translational solutions. The creativity of his translation genius, albeit somewhat unconventional, is indisputably exceptionally communicative for the reader and intriguing and inspiring for the expert analysis.