1. INTRODUCTION

Slovakia has undergone significant changes, especially after 1989 when communism collapsed, and the socialist economic structure transformed into a market economy.16,17 According to Marušiak the transition phase in Slovakia followed similar or mimetic processes as in other countries of the former Eastern Bloc, with efforts to shift towards a more pluralistic and open government and society.18 These changes resulted in a number of changes within sports in Slovakia. Namely, new sport-related legislation now defines the natural and legal persons that constitute the sports ecosystem. A sports professional may perform various functions in sports. Legal persons include sports organisations, such as sports clubs, national sports associations, and other national sports organisations.19 Public authorities form the overall sports structure within the public sector, which operates on three main levels: national, regional, and local. At the national level, central authorities manage sporting affairs, including policymaking, finance, and cooperation with NGOs. The Ministry of Tourism and Sports plays a crucial role in funding sports, with other ministries such as the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defence supporting various sporting initiatives. Regional authorities focus on the development of sports within their regions, supporting the construction and operation of sports infrastructure, and collaborating with local sports organisations to organise competitions and events. At the local level, municipalities support physical culture, the education of sporting talent, and the organisation of local sporting events.20,21,22 This structure is pivotal to the sustainable development of sports in the Slovak Republic and the promotion of physical activity across all age groups.

The sports ecosystem’s specificity represents the funding scheme through a complex system of various public sector actors. The main element is the Sports Funding Formula (SFF), which considers sporting success, interest in sports, and membership up to the age of 23. This formula is crucial for the redistribution of funding at the national level. The Ministry of Tourism and Sports (MTS) is the primary funding body, distributing funds to various programmes. These programmes include support for recognised sports, sports infrastructure, national sports projects, and sport-for-all initiatives. In addition, the MTS provides merit grants for athletes. In contrast, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defence primarily fund their respective sports clubs and organisations. Thhe Government Office also contributes funding, although this is often irregular and mostly related to special projects and support for sporting events. However, perhaps the most important component of funding comes from cities and the higher territorial units (HTUs), with cities providing the majority of the funding. This money is primarily earmarked for sports activities, events, and infrastructure in local communities. However, many authors’ analyses have shown that this funding is not sufficient, making sports in Slovakia often dependent on the commercial sector.23,24,25

The 2017 Concept of Sport Funding in the Slovak Republic revealed that the private sector contributed less than 15% to the total funding of sports.26 Efforts to increase private sector support through sponsorship agreements and super-deduction have faced challenges and setbacks. These issues have been addressed in the 2030 Sports Strategy, which sets out key priorities across six pillars: transparent funding, infrastructure modernisation, education, development of elite sports, promotion of active participation among the population, and digitalisation. The authors of this document identify the most important challenges as the lack of transparency in funding and the low level of sports participation among the population.27

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The disintegration of the Soviet Union served as a catalyst for major geopolitical shifts in the 1990s, significantly impacting emerging countries in Central Europe. Early on, these countries engaged in strategic cooperation with the West, pursuing integration into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). Internally, many of these countries are still navigating the transition, with instances of democratic backsliding observed even after more than three decades.28 This constellation did not bypass the sports sector, which experienced significant changes, particularly regarding ownership transfer and the extent of political presence.29 Despite limited research interest in sport-related policymaking in Central Europe, the interplay between the public sector and the sports movement continues to shape the sports landscape, which is characterized by a culture of public administration and strong bureaucracy.30,31 This seems to be a common feature among post-communist countries, although the governmentalization of sport is neither a new phenomenon nor exclusive to communist countries.32 While sport in leading democracies rests on a high degree of autonomy, the public sector remains closely involved in policymaking due to the importance of sports in health, cultural policy, or broader social cohesion efforts.33 The setup of a sport-related policy network depends on democratic capacity and socio-political structure. For instance, in plural societies like Norway, the executive branch exercises strong coordinating efforts with the sports movement. In contrast, less develop societies, such as those in the Western Balkan, are less pluralistic and more politicized and bureaucratic.34,35,36 Due to the ongoing transition processes, this should be observed in an individual and contextual manner, as the distribution of jurisdictions and competencies often bypass formal institutional settings and regulatory regimes, either contributing to or limiting the consolidation of a coherent sports ecosystem.37 Therefore, the nominal dominance of the public sector should be understood in the context of the historical development of sport-related institutions and the socio-political realm that influences and shapes sport governance. That being said, document analysis will be employed to understand how sports policy has been shaped over different periods, including the development of appropriate institutional arrangements. Given the limited research both nationally and regionally, legislation and policies will be major sources, clustered depending on their origin and nature.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SPORT POLICY

According to the Association of the Learned Law Society (UčPS), the beginnings of the relationship between the state and sports in Slovakia can be tracked back to 1869 (UčPS, 2023).38 Reich Law No. 62/1869 made the teaching of physical education compulsory in real schools in Moravia. These early developments constituted a foundation for contemporary sports. However, it was not until the end of WWII, that the introduction of a more system approach in sports policy development occurred:

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the funding of sports primarily relied on membership fees paid to sports associations and clubs. At that time, there was no concept of full state funding for sports. However, after 1948, the situation regarding the funding of sports changed. Antonín Imla, chairman of the Czechoslovak Union of Physical Education, emphasized that the Union played a crucial role in the national front and served to fulfil state goals.39 This association became the highest body responsible for the development of basic physical education, sports, and tourism in Czecho-Slovakia.40 The new understanding of sports during this period continued the state funding that had already begun during the First Czechoslovak Republic. This resulted in significant changes to Slovak sports, with the full integration of sports into state control and regulation. During this time, sports were heavily subsidised by the state, but also fell under complete state control. This period is also referred to colloquially as the period when sports were the showcase of communism. The organisation of sports in post-1948 Slovakia was strongly directive and subject to the communist sports movement. This period saw the unification of various entities involved in sports, physical education, and tourism, often achieved through violent means. The trends that developed in sports during this time can be characterized by politicisation, militarisation, and centralisation. Politicisation meant that sports became an instrument of political influence and propaganda. Militarisation involved using sports to promote military objectives and prepare youth for military service. Centralisation occurred through the merger of various sports organisations into a unified system under the leadership of the Czechoslovak Sports Federation (CSF).41 These changes weakened the autonomy of the sports movement due to increased state interventionism. Overall, the post-1948 period led to significant changes in the funding and organisation of sports, turning them into instruments of state control and political influence.42

Fundamental changes in the system of sports and its funding emerged with the adoption of Act No. 187/1949 Coll. on the State Care of Physical Education and Sport.43 This Act established the State Committee for Physical Education and Sport, composed of various members, including representatives of the Czechoslovak Sokol Community. In addition, the law required defunct physical education and sports organizations, which had ceased to exist due to unification, to transfer their property to the Czechoslovak Sokol Community. According to Križan, this step can be interpreted as the state de facto taking control of Slovak and Czech sports.44 Later, Act No. 68/1956 Coll. on the Organisation of Physical Education was issued, further centralising the sports system by entrusting the organisation and management of voluntary physical education and its planned development to a single voluntary physical education organisation.45 All existing state committees were abolished, and power was transferred to the new Czechoslovak Union of Physical Education. Its main task was to ensure the overall management and organisation of the entire sports movement, which, by 1979, had as many as 1,703,000 members in 25,240 physical education units.46 However, major changes in the organisation and funding of sports did not occur until 1990. During the period of normalization, there were attempts at democratisation, but political leaders were reluctant to introduce major reforms. Sport was a tool of propaganda and power for them, and the funds associated with sports were significant. The aim was not only to keep sports at a high level but also to use them to promote the socialist regime and its success.47

CZECH-SLOVAK FEDERAL REPUBLIC

In an attempt to preserve the federation, the Government of National Understanding was formed, aiming to establish a more pluralist political system.48 Following this event, significant changes occurred in the field of sports. The first logical step was the decentralisation and nationalisation of sports. Despite these changes, political intervention in sports continued to some extent, particularly with the adoption of Act No 198/1990 Coll.49 This law removed most aspects of the militarisation of sports and transformed sports into a humanising element. It also responded to the increasing commercialisation of sports, the rise of entrepreneurial activity in sports, and the growing role of sponsorship. However, these statutes were basic and did not comprehensively address the entire system in these areas of sports.50 After 1990, the door was opened for more decentralisation and a greater role for private actors in sports, while political influence was still present, but to a lesser extent than under the previous regime.

The new system Slovakia adopted from Western countries proved to be problematic and did not achieve the expected success. Križan characterised this development by noting that sports had to adapt to a freer society, where they no longer occupied the forefront of attention as they did in the communist, state-owned system, with provided generous public funding and other forms of support.51 There was a need for sports to quickly transform into a voluntary sport, or even a sports industry on the territory of Slovakia, similar to the process that occurred in Western European countries over the course of the 20th century. However, it was expected that this transition would happen relatively quickly in Slovakia, even without significant state support. A similar transition of the sports system can be observed in Hungary.52

The summary of the era up to the end of 1992 indicates that the transformation of sports brought more problems than positive results. Among the biggest problems were economic difficulties linked to insufficient funds, non-coordination of cooperation, and privatisation of sports facilities. Other equally important problems included limited state support, the absence of a stable and transparent funding model, the lack of a clear concept for the development of sports, rising costs of sports, the abolishment of sports clubs, the disappearance of training centres, and many other negative factors.53 This era of sports in the Czecho-Slovak Federative Republic was definitively ended by the peaceful division into two separate states, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, in 1993.54

SLOVAK REPUBLIC

The last stage of development in the field of funding and operation of sports spans from 1993 to 2015, marked by the adoption of a new sports act and the introduction of a new funding model that remains in use today, albeit with some modifications. During this era, the number of sports bodies with stable structures and established internal regulations stabilised. Simultaneously, new sports emerged, while some traditional sports saw a decline in popularity. The transfer of competencies in sports from central authorities (ministries) to regional levels that aligned with territorial reforms could be observed as well.55

The era of autonomy in sports began on a positive note with Slovakia’s adoption of several international activities by the Council of Europe, including the European Charter for Sports, the Council of Europe Convention against Doping, and the European Convention on Violence and Spectator Restraint at Sporting Events. During this period, Slovakia also enacted some significant laws, although they were not perfect. One of these laws was Act No. 264/1993 Coll. on the State Fund of Physical Culture, which regulated the conditions for funding sports through lottery companies. Another important legislation was Act No. 288/1997 Coll. on Physical Culture, which focused on education and entrepreneurship in sports and introduced foundational principles in this field.56,57,58

During this era, spanning from 1993 to 1997, there is a notable lack of precise records regarding the funding allocated to sports, as highlighted in the 2004 report on the state of sports in the Slovak Republic.59 One of the main reasons for the decline in financial support for sports was a methodological error dating back to 1993, resulting in an annual loss of 400 million Slovak crowns from the budget. The methodological error was corrected only in 2003, yet its repercussions are still evident today.60 Furthermore, the Government Decision of the Slovak Republic No. 904/2001, which abolished the State Fund of Physical Culture and transferred its financial resources to the Ministry of Tourism and Sports, marked the end of sports and physical education organisations’ ability to influence the allocation of public resources to sports.61

This legislation laid the groundwork for sports regulations, with Act No. 455/1991 Coll. on Trade Business specifying conditions for business activities. These acts intersected by regulating state budget funding, business sponsorship, taxes, and compliance for activities and entities involved in sports within the country. Overall, the relationship between these acts and sports funding is complex and multifaceted. However, it is clear that the state budget allocations and business support facilitated under these acts play a vital role in supporting the development of sports in Slovakia.62,63

After 2004, the Slovak Republic introduced a new organisational structure for sports funding aimed at streamlining and eliminating redundant elements, although it remained a complex and somewhat inefficient system. Between 2010-2012, a new concept was adopted to promote sports in schools, support interest groups, encourage volunteering in sports, and address various organizational issues within the sports sector. The 2015 Act on Sports, including its later amendments, sets out the current rules for sports funding in Slovakia. However, critics argue that the Act has been less effective following policy changes compared to its original intent.64 The remainder of this article analyses the form and implementation of the current Act on Sports, which is why it has not been discussed in more detail within this chapter.

UNDERSTANDING THE SPORTS ECOSYSTEM IN SLOVAKIA

Slovakia, as a member of the European Union, has undergone various changes in the past that have impacted its economic, political, legislative, and social life of the country. The last significant change occurred after 1989, when the communist regime fell in former Czechoslovakia. This marked the collapse of the socialist economic structure. Morvay et al., define this economic transformation as an effort to establish a functional market mechanism capable of generating strong sustainable growth, thereby eliminating distortions and facilitating equal interactions with more advanced market economies.65 Thus, Slovakia has been undergoing a gradual transformation towards becoming a market-oriented economy.

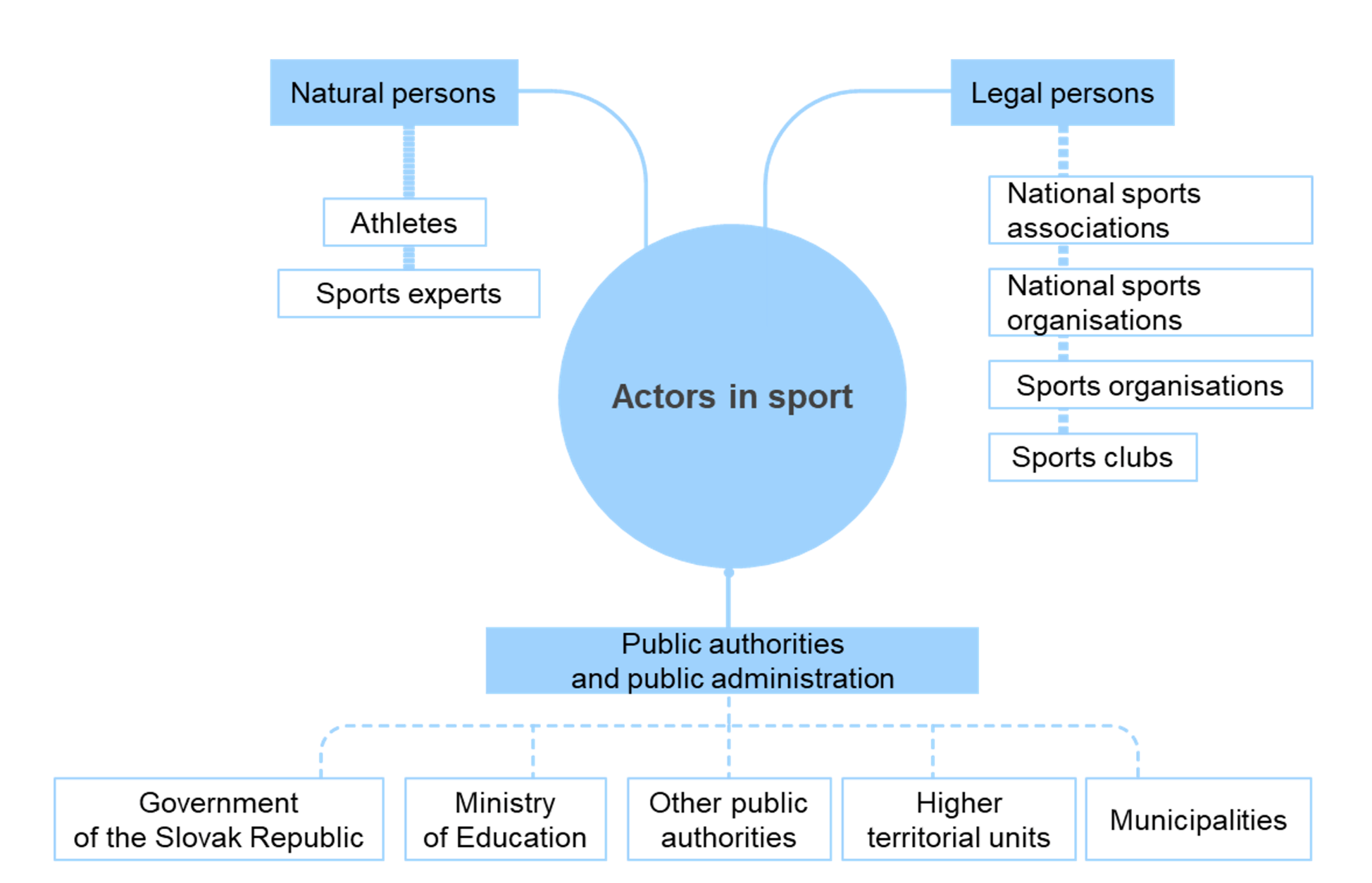

This transformation was logically connected to the introduction of a new Civil Code, which aimed to encompass various legal aspects and definitions related to this concept. The Civil Code has undergone several revisions since its inception. In its most recent edition, similar to the business sector, it classifies entities in sports into natural persons and legal persons. Specifically, Act No 440/2015 Coll. on Sports and on Amendments and Additions to Certain Acts (hereinafter, the 'Act on Sports') addresses this issue in greater depth. In addition to natural and legal persons in sports, the activities of public authorities and public administration bodies can be observed. These are particularly important from the perspective of sports funding.66 Changes to sports funding have made it easier to obtain the funds, introduced new funding methods, and simplified the monitoring of expenditures. Previously, different funding rules applied to sports organizations depending on whether they were set up as non-profit groups or businesses. This simplifies fund allocation, as the separation of funding for individuals and organizations has made it easier to verify how the money is spent.67 A closer look at this division can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Entities active in sports in Slovakia

Source: Own elaboration, 2023

Natural persons

According to the Sports Act, individuals involved in sports are categorised into athletes and sports professionals. There are three categories of athletes: professional, amateur, and unorganized athletes (recreational). Only professional and amateur athletes are eligible to participate in organized sports events representing organizations registered in the official registry.68 Professional athletes are required to perform sports activities based on a contract for professional sports performance or another contract if they perform sports for a sports organization as self-employed individuals. Prior to 2016, the status of professional athletes was not regulated, with athletes signing contracts according to Civil or Commercial Laws, which constituted a breach of Labor Law provisions from 2007.69 Since 2016, the status of athletes has gradually improved, allowing them to be considered employees or self-employed under a special type of employment – sports employment – which constitutes an employment relationship.70,71,72 However, the legislation introduced a transitionary period of five years, providing athletes the option to choose between a contract for professional sports performance and other types of contracts. This legal provision has led to ambiguity regarding the legality and predictability of labor relations in sports, particularly the position of professional athletes, while favoring sports organizations.73

Conversely, amateur athletes engage without formal contracts, with their participation limited to working no more than 8 hours weekly, five days per month, or 30 calendar days. Talent and activity in athletes are categorized into two groups: talented athletes and active athletes. Talented athletes are under 23 years old, showcasing exceptional skills, and are listed in the talent registry.74 Active athletes are those who have in a minimum of three competitions organized by their registered sports organization in the past year, excluding "sports for all" events.75 Regarding sports professionals, their operations can be classified as either volunteer-based or business-based classifications. The law recognizes sports coaches, instructors, officials, and inspectors as sports professionals.76 They can perform their roles as a business, based on a contract for professional activity, within an employment relationship or a similar employment relationship, as volunteers, or without a contract (§ 6, para. 3 of Act No. 440/2015 Coll.).77 The performance of sports professionals’ activities is always determined by the specific nature of the sports activity they are involved in, whether it meets the characteristics of dependent work, business, or can be performed as a voluntary activity.

LEGAL PERSONS

The Sports Act delineates three types of non-governmental sports organizations with legal status: sports clubs that foster engagement and prepare individuals or teams for sports events; national sports associations recognized by the Ministry of Education that hold an international sports body membership, control specific sports in Slovakia, and aid athletes for international contests; and other sports bodies like the Slovak Olympic and Sports Committee and the Slovak Paralympic Committee acknowledged by the Ministry, these bodies have two-year affiliations with international sports organisations and govern particular sports sectors within Slovakia, such as Deaflympic sports, Special Olympics, university sports, school sports, and sports for all.78

PUBLIC AUTHORITIES AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

Under the major reforms initiated between 2003 and 2006, the public sector system was reformed into a deconcentrated state administration with a new structure established.79 The Sports Act’s fourth part outlines the roles of public authorities and public administration entities in the field of sports, which include the Government of the Slovak Republic, the Ministry of Education, other central authorities of state power, self-governing regions, and municipalities.80 The Government of the Slovak Republic is responsible for approving concepts for the development of sports and other materials related to state policies in the field of sports. Additionally, the government approves guarantees for significant competitions and decides on the construction, modernization, and reconstruction of nationally significant sports infrastructure. Lastly, the government makes decisions regarding specially supported sports, which are recognized as sports for all.81 Regarding the government’s support for the sport for all concept and the National Sports Federations (NSFs) it involves, the aim is typically to encourage broad sports participation. While specific NSFs may focus on different sports, the government's emphasis on sports for all generally involves supporting initiatives that promote inclusivity and accessibility to sports across various disciplines and communities.82,83,84

THE STRUCTURE OF THE SPORTS ECOSYSTEM

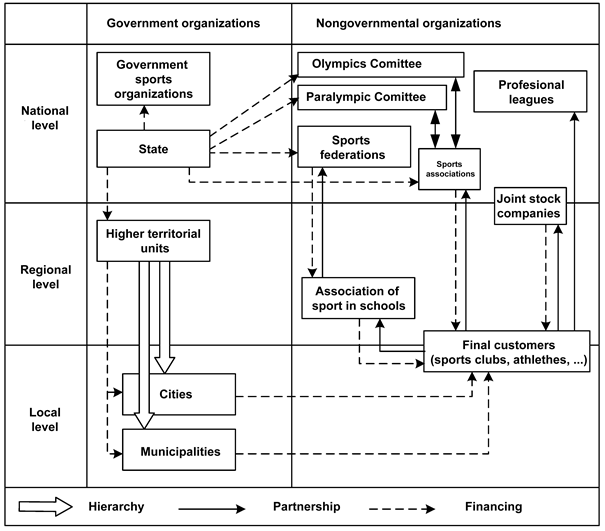

The structure is based on three levels: national, regional, and local levels, interrelated in contributing to coherent structure.

Figure 2 – Sports funding model in Slovakia

Source: Varmus et al. 2018

The legal nature of professional sports leagues in the Slovak Republic is complex and depends on the specific league and sport. Generally, these leagues are established as separate legal entities according to the Civil Code. They can take several forms including civil associations, non-profit organisations, or commercial.85 Some professional sports leagues are directly managed by national sports associations (NSA). For example, the Slovak Ice Hockey Extraliga is managed by the Slovak Ice Hockey Association.86 Other professional sports leagues operate independently of the NSA. For instance, the Slovak Basketball League is governed by a separate association called the Slovak Association of Basketball Clubs.87 In some cases, professional sports leagues may cooperate with the NSA. For example, the Slovak Football League is governed by the Slovak Football Association but also has its own governing bodies.88

NATIONAL LEVEL

The central government in Slovakia is responsible for the management and coordination of sport-related matter. This includes the development of national policies, legislation, and financial frameworks to support sports development. Additionally, the government collaborates with non-governmental organisations and provides subsidies to sports associations from the state budget. There is no permanent parliamentary body responsible for sports in the Parliament of the Slovak Republic. However, this will change as of 1 January 2024, when the new Ministry of Sport and Tourism of the Slovak Republic will be established, leading to the introduction of an appropriate parliamentary body to oversee sports developments.89 Currently, the area of sports is entrusted to several committees, in particular the Committee on Education, Science, Youth, and Sport; the Committee on Social Affairs and Families; and the Committee on Culture and Media. The government is also responsible for sports education and international cooperation. In addition, the central government is responsible for youth policy, which includes the preparation of conceptual and decision-making materials and the coordination of the government’s activities in the planning and implementation of youth policy. They also provide technical, organisational, and substantive support to the activities of the Intergovernmental Working Group on Youth Policy. The central government prepares legislation and establishes conditions for financial support to youth organisations and other institutions providing services to children and youth. This represents an important parameter that plays a central role in setting sports promotion within youth categories.90,91,92

Furthermore, the central government guarantees cooperation between government and local levels of youth policy and creates conditions for the work of children’s and youth organisations. They also coordinate the work of the Accreditation Commission for Youth Work Programmes, including issuing certificates for accredited institutions. To support these activities, the central government publishes research, analytical and forecasting documents, and organizes workshops, conferences, and training sessions for representatives of regions, cities, and municipalities, along with youth and youth workers.93,94,95

The funding of sports as a separate category primarily falls under the role of the Ministry of Tourism and Sports of the Slovak Republic.96 However, this does not mean that other ministries are not involved in the funding of sports at the national level. For example, the Ministry of the Interior funds the police sports clubs, the Ministry of Defence allocates funds for the military sports centre, and the Office of the Government, along with subsidies from the Prime Minister's Reserve, funds various sports projects.97,98,99

REGIONAL AND LOCAL LEVEL

Regional sports strategies in Slovakia are aligned with national directives. In 2021, the 2021-2030 National Sports Strategy of the Slovak Republic was approved. This strategy sets the basic objectives and priorities for sports nationwide. Thus, the management of sports in regions and cities remains within the limits of adaptable cooperation.100

At the regional level in Slovakia, self-governing regions take charge of sports development initiatives, focusing on infrastructure construction, maintenance, and operation in collaboration with municipalities and sports organizations. They manage sports facilities in secondary schools, emphasizing on youth engagement and covering associated expenses. Self-governing regions also collaborate with federations and clubs to establish sports centres, offering sports opportunities, especially for youth, under expert guidance. Additionally, they actively promote and host significant inclusive sports events, thereby enhancing sports participation and providing opportunities for the disabled within their regions.101,102,103

At the local level, municipalities act as public authorities and entities responsible for developing sports development concepts tailored to their municipal conditions. They support the construction, modernization, reconstruction, maintenance, and operation of sports infrastructure within the municipality, including ensuring the utilization of sports infrastructure in elementary schools they establish. Furthermore, municipalities participate in organizing sports activities for all, with an emphasis on youth, often in cooperation with sports federations and sports clubs. For instance, in Považská Bystrica, the association of sports clubs operates under the city’s administration. Municipalities, alongside sports associations and clubs, establish sports centres aim at conducting sports activities for all, particularly youth, guided by sports experts. In addition, municipalities participate in creating conditions for sports for all practices and sports competitions, including those for disabled individuals within the municipality. Finally, municipalities acknowledge and reward athletes and sports professionals active within their community.104,105,106 To operationalize these responsibilities, municipalities allocate budgets, make administrative decisions through mayor's offices or dedicated sports departments, collaborate closely with sports entities, and initiate specific funding programs or grants. Funding sources typically include budget allocations, government grants, and partnerships with higher authorities. Decision-making processes involve various administrative bodies and adapt based on the municipality's structure and available resources.107,108,109

THE SPORTS FUNDING SYSTEM

The interrelation between different levels of the public sector is based on a comprehensive policy framework governing state funding priorities in sports, largely shaped by the sports funding formula.

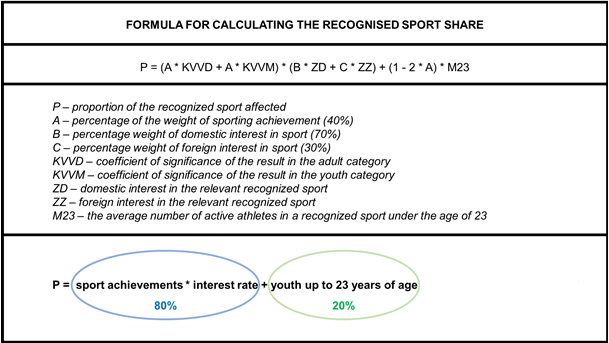

THE FORMULA FOR CALCULATING THE RECOGNISED SPORTS SHARE

The Recognised Sport Share (RSS), created in response to the Sports Act, is a formula designed by experts within the sports movement to enhance transparency in funding allocation. This formula, outlined in paragraph 68 of the Sports Act, comprises three main components. The first part represents sporting success and depends on the coefficient of significance of the result in the adult category or the coefficient of significance of the result in the youth category. Overall, this part accounts for 40% of the whole formula. The second part of the formula consists of interest in sport or, in other words, the popularity of sport. Within this category, the foreign interest in sport and domestic interest in sport are considered, with domestic interest playing the primary role and accounting for up to 70%, while foreign interest accounts for the remaining 30%. As with the first category, this part accounts for 40% of the whole formula. The last part of the RSS is the average number of active athletes in a recognised sport under the age of 23. This part logically accounts for the remaining 20% of the formula.110,111,112

Simplistically, this RSS notation could be expressed as P = sporting success * interest in sport + membership under 23 (detailed description included in Figure 3). Thus, greater sporting success with increased interest and higher youth membership, all contribute significantly to the funding allocation.113

Figure 3 – The formula for calculating the share of recognised sports

Source: Greguška (2019)

The formula for the share of recognised sport applies exclusively at the national level. At the regional or local level, financial support for sport is determined by the decisions of individual self-governing regions or municipalities. In most cases, these decisions are governed by general binding regulations and respond directly to the various subsidy calls issued by the municipalities or self-governing regions.114,115,116

The formula as a whole is very complex, evolving constantly and subject to various legislative amendments. This was also documented by Žaneta Surmajová (2022), Director General of the Legislative and Legal Section of the Ministry of Education, a member of the Council of the UčPS and Vice-Chair of the Chamber for Dispute Resolution (SFA). During a presentation at the Sport and Law 2022 event, she discussed that there has been a total of 13 amendments to the law since 2016, which were not merely technical in nature. In 2019, the UčPS team provided a detailed explanation of the formula to the entire sports sector and the general public involved in this matter. This was in response to demands for a better explanation during the inter-ministerial comment procedure. However, this explanation did not become a sufficient priority from the perspective of the Ministry of Education and Science.117 A closer view of the formula can be seen in Figure 3 above.

FUNDING OF SPORTS BY INDIVIDUAL ORGANISATIONS

Varmus et al. 2023 underlined that the municipalities and the Ministry of Education and Sports of the Slovak Republic play the most important roles in the funding of sports in Slovakia. This is mainly because they manage the largest allocations of money dedicated to sports.118,119

Funding for sports activities via the Cabinet Office and the institution of the Prime Minister’s grant is often irregular, making reliance on this source risky. Allocation of the Prime Minister’s subsidies for the promotion of sports is regulated by Slovak Government Regulation No.440/2017 Coll. on the provision of subsidies from the Prime Minister's reserve. This Regulation stipulates that subsidies from the Prime Minister may be provided to support projects in the field of sports that contribute to the development of sports in Slovakia. The Prime Minister’s Reserve is an extra-budgetary fund intended to cover emergency situations, with the promotion of sports falling under the discretionary power of the Prime Minister. This means that the Prime Minister decides which projects will be supported and the amount of the subsidy.120 The competence to propose the allocation of these subsidies for the promotion of sports lies with the Ministry of Tourism and Sports of the Slovak Republic. The allocation of these subsidies is often linked to projects intended to raise the level of sports in Slovakia. Specific examples supported by these subsidies include: organisation of sporting events (e.g., support for the Women’s European Championship – CEV EurovVolley 2019), modernisation of sports facilities (e.g., the construction of a multifunctional playground in the municipality of Valča), support for training and coaching of athletes (e.g., the purchase of timing devices for firefighting sports competitions), and promotion of sport and health improvement projects to prevent health problems (project: 'Let's do sport – in summer and in winter').121

Table 1 – Distribution of the share of sports funding by individual organizations (in millions of euros)

Note: MTS = Ministry of Tourism and Sports of the Slovak Republic; MI =Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic; MD = Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic; GO = Government Office; SA = subsidy allocation; HTUs =higher territorial units.

Source: Varmus et al., 2023

Allocation of funds by the central body of the Ministry of Tourism and Sports of the Slovak Republic (previously the competent Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport) amounts to a total value of € 532.97 million in the period between 2017-2021. The largest share of funding overall goes to recognised sports (hereafter referred to as RS), which are funded through the RSS. Over the last three years this funding has remained stable, ranging between € 56-58 million annually. The total funds allocated for this programme during 2017-2021 were € 251.39 million.122 The second largest sector is the sports infrastructure. This separate category is mainly devoted to funding the Football Stadiums 2013-2022 project under UV SR No. 115 of 27.2.2013. A third part of the funding goes to the Sports Promotion Fund. The last big category in terms of funding significance is the category of national sports projects. This category was funded totaling €65.59 million, covering the costs for the Olympics in Tokyo, ensuring the preparation and participation of the sports representation in the XVI Paralympic Games in Tokyo, providing rewards to youth coaches for their athletes’ medal placements at major international events in 2020, and supporting activities and tasks related to university sports in 2021, among others. This funding distribution confirms orientation toward high-performance sports, including support for the Slovak Anti-Doping Agency and the National Sprots Centre. However, programmes promoting sports for all are underfinanced.123,124

Table 2 – Distribution of funding of the MTS for individual sports programs (in million €)

Note: SFA = Sports for all; RS= Recognised sports; NSP = National sports projects; SI = Sports infrastructure; TA = Transversal activities; P_021 = Program 021

Source: Ministry of Tourism and Sports of the Slovak Republic, 2023

The Ministry of the Interior is not a very significant contributor to sports funding. The funding of the department is primarily concentrated on police sports clubs and the Union of Sports Organisations of the Police of the Slovak Republic. Regular allocations for sports from this department amount to around 750,000 euros, with no funding provided during the COVID-19 crisis (MVSR, 2023).125

Table 3 – Distribution of the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic funding for individual sports programs (in million €)

Note: PSC BA = Police Sports Club Bratislava; PSC KE = Police Sports Club Košice; PSC BB = Police Sports Club Banská Bystrica; UPEOP SR= Union of Physical Education Organizations of the Police of the Slovak Republic; OPSC = Other Police sports clubs

Source: Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic, 2023

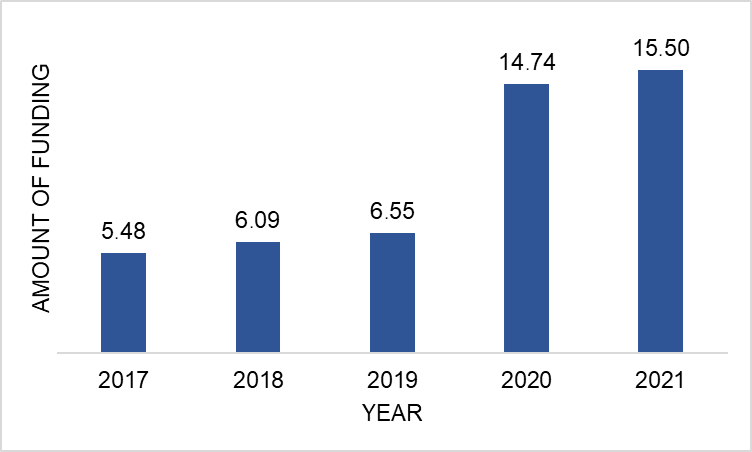

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) plays a key role in supporting athletes of the Dukla Military Sports Centre. The total budget allocated for this purpose over the period 2017-2021 amounted to €48.36 million, primarily focusing on high-performance sports.

Figure 4 – Development of the MoD budget allocated to the sports section (in million €).

Source: Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic, 2023

The Dukla Military Sports Centre supports a large number of recognised sports, most of which have a section included within Dukla Banská Bystrica. Others, such as road cycling, water slalom, or speed canoeing, are managed by sections located in three other centres, which are Dukla Liptovský Mikuláš, Dukla Trenčín and Dukla Žilina.126

From the perspective of sports funding, HTUs, and cities in Slovakia, it can be stated that HTUs contribute an estimated 1% of all financial resources allocated to sports, among the financial package for sports from cities and HTUs. The remaining 99% of allocations are covered by cities. These funds are primarily used for the operation of recognised sports, the organization of sports events, and the development of sports infrastructure in cities and counties. More detailed results of this funding distribution are contained in the authors’ research projects.127,128,129

SERVICE PROVIDERS IN THE FIELD OF SPORTS

Analyse the commercial sector of sports in Slovakia is challenging, as evidenced by the Concept of Sports Funding in the Slovak Republic (2018). Revenues from sponsorship, donations, and similar private company sources accounted for less than 15% of the total funding for sports in Slovakia. More recent data are currently unavailable. The authors of this study argue that this low percentage indicates that Slovakia, as an EU country, is below average compared to other European countries.130

Paradoxically, another study conducted by the authors showed that when surveyed by TNS Slovakia and Strategy magazine about the status of sponsorship in marketing, 40% of marketing managers indicated that sponsorship is a stable part of marketing communication. Furthermore, 34% confirmed that sponsorship should be considered a stand-alone marketing tool. Only 3% of executives viewed sponsorship as a waste of money.131

In recent years, attempts have been made to increase financial support from the private sector in two ways. The first is the sponsorship agreement, defined in sections 50 and 51 of the Sports Act, which allows sponsors to provide support to athletes, sports professionals, or sports organisations that are members of sports federations.132 The second measure is the institution of the super-deduction, intended to incentivise the private sector to invest funds in sports through sponsorship agreements. Despite some advantages, the super-deduction was not included in the amendment to the Income Tax Act and is not currently in force.133

A sports sponsorship contract combines the concept of a specialised gift with advertising, primarily aimed at supporting the sponsored entity’s sporting activities (90%), while secondarily promoting the sponsor’s name or brand (10%).

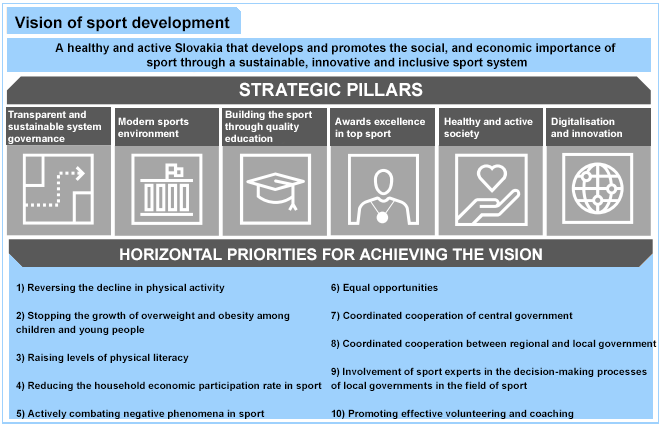

STRATEGIC PRIORITIES FOR BUILDING SPORT

The key priorities for building the future of sports in Slovakia are outlined in the strategic document titled " Sport Strategy 2030" or " Vision and Concept of Sport Development in Slovakia until 2030." This document outlines the future vision for sports, drawing on international best practices. Over the next decade, the primary goal is to elevate sports, athletes, and the sports industry to a status that mirrors their societal and economic contributions. The Slovak Olympic and Sports Committee aims to enhance global visibility through sporting achievements while ensuring universal access to sports for all citizens, regardless of location, age, living conditions, or health limitations. This includes promoting sustainable growth in the sports economy, modernizing sports infrastructure, enhancing sports education, encouraging physical activity among children, and promoting healthy lifestyles. Embracing innovations and modern technologies within the sports domain is equally pivotal.134,135,136

Figure 5 – Strategic Priorities for Building Sports in Slovakia

Source: Slovak Olympic and Sports Committee (2021), modified according to Varmus et al. (2023)

The strategic pillars of the Sport Development Concept by 2030 are based on the main objectives of the Sport Strategy 2030 project. These pillars are developed hierarchically across various levels, ranging from the main areas of development to specific projects and initiatives. Each of the six strategic pillars has defined main objectives, stakeholders, challenges, risks, and key principles for the development of sports in that area, along with an implementation plan. A closer description of these pillars looks as follows:

Enhancing funding models for long-term sports growth.

Boosting GDP contribution, cutting healthcare costs, creating jobs, and aligning with EU funding.

Updating infrastructure, building modern facilities.

Cutting investment debt, improving elite training, adopting innovative solutions.

Elevating physical education standards at all levels.

Improving school resources, training coaches, enhancing management skills.

Fostering youth talent, supporting elite athletes.

Boosting international successes, providing career support, and applying modern solutions.

Encouraging sports participation and healthier lifestyles.

Implementing 'Slovakia Is Sporty,' devising plans, creating aid schemes.

Additionally, it is worth mentioning the document from the Ministry of Investment, Regional Development, and Informatization of the Slovak Republic titled "Proposal for the Vision and Strategy for the Development of Slovakia by 2030 – Long-term Strategy for Sustainable Development of the Slovak Republic." This document discusses long-term sports development in Slovakia with a focus on supporting families, optimizing financial planning, and building sports infrastructure.139

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

From a theoretical standpoint, the primary challenge in building sports in Slovakia can be identified as the transparency of funding. The formula for recognised sport share serves as an indicator of system allignment and transparency, even if it does not work perfectly. Previous research highlights this issue, particularly at the regional or local levels where such a transparent system is absent.140,141,142 On the contrary, the Ministry of Tourism and Sports s of the Slovak Republic identifies the biggest challenges in the field of health in the context of sports development. Within the strategic document titled " Concept of Sport 2022-2026," the following challenges are included:

new epidemics and pandemics, including civilization-related diseases and obesity.143

Building on this information, it can be argued that while researchers perceive the primary challenges in sports primarily in terms of establishing effective funding, the MTS SR, as the central body responsible for sports administration, perceives the problems and challenges of sports, especially in terms of physical and mental well-being. The leadership of the Slovak Olympic and Sports Committee (SOŠV) acknowledges the connection between these issues. in May, they issued the " Declaration of Slovak Sports 2023," which discusses the most pressing issues of Slovak sports. Within this declaration, efforts can be seen to adjust the competency classification of sports within the highest executive bodies of the state, affirming and emphasizing its universal character. According to the SOŠV, sports should not be an unwanted appendage of any ministry; rather, it should be managed by an authority for where it holds a top priority. Another aspect highlighted is funding itself, which should be sufficient and systematically structured to maximise effectiveness across all forms and levels, both at the state and local levels. Other challenges addressed the establishment of a unified National Sports Development Program, ensuring the renovation and construction of sustainable sports infrastructure, guaranteeing long-term, systematic, and transparent support for national sports representation, promoting sports as an integral part of education, and introducing a comprehensive system of sports certifications for young people.144,145

The lack of coordination horizontally within the central public sector (government and ministries) and at the sub-national level (regions and local communities) in promoting sports often results in segmentation and fragmentation of resources. This can constrain the effectiveness and impact of support. Synergies and coordination between these levels are key to ensuring that financial and organisational resources are effectively utilized to support and develop sports activities and programmes nationwide. Improved collaboration among government bodies, local communities, and sports stakeholders can foster synergistic efforts and create a better environment for the growth and promotion of sports at different levels of society.

Bibliography

Grexa, Jan. Míľniky slovenského športu. Bratislava: Slovenský olympijsky výbor, 2018.

KPMG. “Koncepcia financovania športu v Slovenskej republike“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.olympic.sk/sites/default/files/2021-01/KPMG-koncepcia-financovania-sportu-SR-2018.pdf.

Kolník, Peter. “Šport a právo: Zmeny v Občianskom zákonníku a ich vplyv na financovanie športu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.upjs.sk/sites/default/files/pdf/casopis/2017/10/95.pdf.

Križan, Ladislav. “Od hyperaktívneho štátu k štátu nevládnemu: história vzťahu štátu – športu – práva na území Slovenska“. Accessed October 10, 2023.http://www.ucps.sk/clanok-0-1455/Od_hyperaktivneho_statu_k_statu_nevladnemu_historia_vztahu_statu_%E2%80%93_sportu_%E2%80%93_prava_na_uzemi_Slovenska.html

Laposová, Helena. “Metodika na výpočet podielu uznaného športu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.isamosprava.sk/clanky/metodika-na-vypocet-podielu-uznaneho-sportu/.

Marušiak, Juraj. “The Paradox of Slovakia’s Post-Communist Transition“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.rosalux.de/en/news/id/44863/the-paradox-of-slovakias-post-communist-transition.

Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic,“Detailný rozpočet v roku 2023.“ Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.rozpocet.sk/web/#/rozpocet/VS/kapitoly/0/kapitola/11/detail/f/2021/DEBT/FNC.

Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, “Financovanie športu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.minedu.sk/financovanie-sportu/.

Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic. “Koncepcia športu 2022 – 2026“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.minedu.sk/data/files/11170_koncepciasportu2022.pdf.

Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic. “Národné športové projekty“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.minedu.sk/narodne-sportove-projekty/.

Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic. “Prieskum športu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.minedu.sk/data/files/11275_ipsos_sekcia_sportu_prieskum_sportov_2022_na_minedu.pdf.

Ministry of Investments, Regional Development, and Informatization of the Slovak Republic, “Návrh Vízie a stratégie rozvoja Slovenska do roku 2030 - dlhodobá stratégia udržateľného rozvoja Slovenskej republiky – Slovensko 2030 – nové znenie“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://mirri.gov.sk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SLOVENSKO-2030.pdf.

Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic. “Dotácie“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.minv.sk/?dotacie-1.

Morvay, Karol. Transformácia ekonomiky: skúsenosti Slovenska. Bratislava: Retro-print, 2005.

Office of the Government of the Slovak Republic. “Dotácie ÚV SR“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.vlada.gov.sk/dotacie/.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Správa o plnení úloh a súčasnom stave športu v SR“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.nrsr.sk/web/dynamic/Download.aspx?DocID=189402.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon č. 440/2015 o športe a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2015/440/20210101.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o organizácii telesnej výchovy“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1956/68/19570101.html.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o štátnej starostlivosti o telesnú výchovu a šport“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1949/187/.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o Štátnom fonde telesnej kultúry“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1993/264/19940101.html.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o telesnej kultúre a o zmene a doplnení zákona č. 455/1991 Zb. o živnostenskom podnikaní (živnostenský zákon) v znení neskorších predpisov“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1997/288/20140201.html.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o telesnej kultúre“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1990/198/19900518.html.

Parliament of Slovak Republic. “Zákon o živnostenskom podnikaní (živnostenský zákon)“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1991/455/19980701.html.

Perényi, Szilvia. “Hungary“. In Comparative Sport Development Systems, Participation and Public Policy. New Zork: Springer, 2013.

Slovak Association of Basketball Clubs. “Stanovy Slovenskej basketbalovej asociácie“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://slovakbasket.sk/userfiles/file/Stanovy_2021.pdf.

Slovak football association. “Stanovy Slovenského futbalového zväzu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://mediamanager.sportnet.online/media/pages/f/futbalsfz.sk/2022/03/2022-02-25-ksfz-stanovy-sfz-novela-1.pdf.

Slovak ice hockey association. “Stanovy Slovenského zväzu ľadového hokeja“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.hockeyslovakia.sk/userfiles/file/Stanovy/STANOVY%20SZ%C4%BDH.pdf.

Slovak Olympic and Sports Committee. “Stratégia športu“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.olympic.sk/sites/default/files/2022-05/Sport_2030_Phase_II_PwC_v6.pdf.

Slovak sport portal. “Šport v rokoch (1945 - 1992)“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://sport.iedu.sk/Page/sport-v-rokoch-1945-1992.

Šimo, Marián. “Vláda dá do parlamentu sterilnú správu o športe“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.olympic.sk/clanok/vlada-da-do-parlamentu-sterilnu-spravu-o-sporte.

Šisolák, Jaroslav. “Aké je postavenie športu v slovenskej spoločnosti ?“. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://futbalnet.tv/ake-je-postavenie-sportu-v-slovenskej-spolocnosti.

TASR. “Deklarácia slovenského športu 2023 pomenúva najpálčivejšie problémy. Accessed October 10, 2023.https://www.teraz.sk/sport/sosv-schvalil-deklaraciu-slovenskeho/717097-clanok.html.