1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade tourism has been an important economic activity in Portugal and is even considered the country’s largest exporting economic activity. It facilitates the development process of many regions, without which a better quality of life for their population wouldn’t have been possible. Tourism development causes multiple positive and negative effects so strategic planning can be an important instrument to manage these effects. Strategic planning in the tourism area can be considered a tool of the economic and social policy of a country that ensures a more balanced and sustained development. It can contribute to reduce regional disparities and ensure a more harmonious and better distribution of equipment, infrastructure, economic activities and use of the territory.

The leading objective of this paper is to analyse the main strategic instruments that have been defined and implemented in Portugal and guided the national strategy for tourism development throughout the last two decades. Another purpose of the paper is to presents some of the results achieved using these strategic planning instruments in the area of tourism, identifying the main challenges for the Portuguese tourism in the future. We will try to appraise the major benefits that resulted from these instruments and try to identify the areas that still need further improvement.

The methodology adopted was the documental analysis, based in the exploration of the different strategic planning instruments used in Portugal over the last two decades, in order to identify the main areas of intervention during this period. After that, we collected data from a variety of institutional sources, which allowed us to study the evolution of various social and economic indicators regarding tourism. The main indicators for tourism development (arrivals, receipts, guests, overnights and jobs) were analysed, in order to evaluate the efficiency of the planning instruments that were adopted (measured by the variation of those indicators, but also by the variation of the industry’s contribution to the GDP). Taking also in consideration some of the megatrends for the sector, we were able to identify various challenges that still lie ahead.

This text is organized in three main chapters: the first is reserved for the literature review about strategic planning and tourism planning; the second one deals with the strategic tourism planning instruments used in Portugal over time; and the third analyses the major economic indicators related to tourism and identifies the aspects that still need to improve to continue promoting the development of the activity in Portugal.

2. STRATEGIC TOURISM PLANNING: LITERATURE REVIEW

2. 1 Strategic planning in tourism

Despite the origin of the concept of strategy being very much associated with the military field, nowadays it is also related with the ability to manage and lead organizations and has multiple contributions from the areas of management and administration. In literature, it is possible to realize that each author in each temporal context has contributed to a better conception of what is strategy.Mintzberg et al. (1998) categorizes the different views of strategy in ten schools of strategic thinking. The concept of strategic planning fits into the Planning School thus designated byMintzberg et al. (1998:48) that understands strategy formation as a formal process (that is analytical, detailed and decomposed into distinct phases).

In a general way planning is a function of the management process, in which the objectives and the ways to fulfil them are defined. According toWilliams (2003:126) “‘Planning’ has been defined in various ways, but a common perspective recognises it as an ordered sequence of operations and actions that are designed to realise either a single goal or a set of inter-related goals and objectives.”

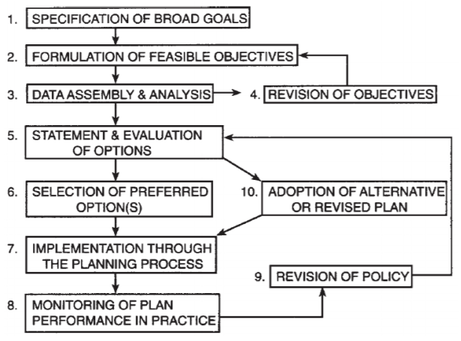

Williams (2003:127) presents a general model of the planning process in which the principal elements in devising and implementing a plan are envisaged as a series of key stages:

Source:Williams (2003:127)

In the tourism sector the need for planning is clearly visible when comparing experiences of success of most of local rationally planned tourist destinations with the negative experience of many unplanned locations verifying negative impacts and low levels of tourist satisfaction. ForWilliams (2003:125) the absence of planning brings evident risks for tourism development because it “will become unregulated, formless or haphazard, inefficient and likely to lead directly to a range of negative economic, social and environmental impacts.”

Williams (2003:129-130) presents some reasons to justify the importance of planning in tourism:

Provides a mechanism for a structured provision of tourist facilities and associated infrastructures;

Permits the co-ordination of activity;

Allows at conserving resources, but also at maximising the benefits to local populations;

Provides a mechanism for the distribution and redistribution of tourism-related investment and economic benefits;

Gives the industry a political significance (since most planning systems are subject to political influence and control) and therefore provides a measure of status and legitimacy;

To anticipate likely demand patterns and to attempt to match supply to those demands;

To maximise visitor satisfaction.

According toTeixeira (2005:49), strategic planning, unlike other levels, aims to anticipate the longterm future, including the definition of objectives and the ways of action to achieve them. Strategic decisions have long term impact, such as the ones that imply the definition of products, services, markets, the development of destinations and regions, high investments, among others. According toFerreira (2009:1520), planning must be seen as a critical element that guarantees, in the long term, the sustained development of the tourist destination. ToCarvalho & Costa (2014:2) strategic planning in tourism is crucial as a tool for the development of the regions, since it can help in the planning and qualification of the territory, guide public and private investment, strengthen the qualification of human resources and the development of products and destinations.

Tourism development at the international level has increased competition between destinations, resulting in a number of positive but also negative impacts. Planning can be the answer to achieve, on the one hand, the maximization of income from this activity and, on the other hand, minimizing its negative effects. Due to the set of peculiar resources used and effects that derive from tourism over diverse sectors, then the development of these activities should be based on a planning process that includes a solid assessment of the destination resources and their attractiveness potential and an assessment of possible impacts.

The negative effects of mass tourism brought to the discussion the concept of sustainable development of tourism.Holden (2008:171) refers that there is an evident need for the environmental planning and management of tourism, because of the sometimes negative interaction between tourism and the natural environment and that has become a concern to different stakeholders in tourism as governments, NGOs, local communities, donor agencies and the private sector.Hall (2000) proposes a sustainable approach of the tourist planning or, in other words, an integrated tourism development planning. This means that tourism planning must be able to articulate the physic and economic dimension of tourism, ensuring, in a long-term, the viability of the tourism industry. The author identifies that strategic long-term tourism planning has three objectives: conservation of tourism resource values; experience of visitors who interact with tourism resources; and maximizing economic, social and environmental returns for the communities’ stakeholders. ForTribe (2004:380) sustainability can be that level of development which does not exceed the carrying capacity of the destination and, thus, does not cause serious or irreversible changes to the destination and that can sustain itself in the long run.

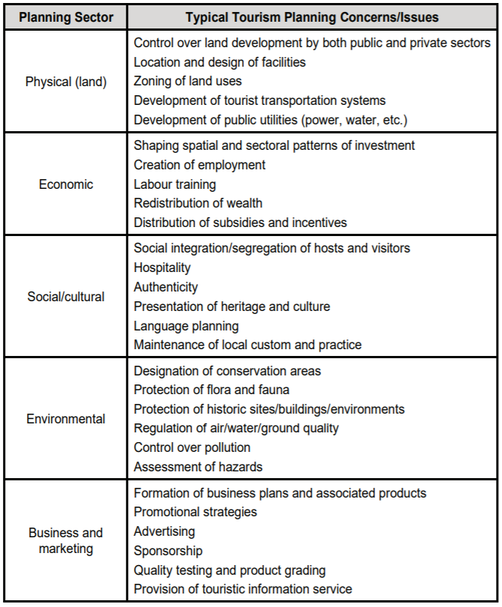

ToWilliams (2003:131) tourism planning, as a concept, is characterised by a range of meanings, applications and uses because it encompasses many activities; addresses physical, social, economic, business and environmental concerns; involves different groups, agencies and institutions; may be exercised by both the public and the private sectors and be subject to varying degrees of legal enforcement; works at local, regional, national and (occasionally) at international scales.Table 1 summarises a cross-section of applications within the broad realms of tourism planning according toWilliams (2003:132).

In summary strategic planning in tourism is a long-term process that can encompass different scales, sectors and activities.

2. 2 Tourism planning at the national level

Usually Tourism planning at national level represents in a country the higher level of policies to develop this sector. National plans and policies define the main orientations of tourism development and are the guidelines to elaborate regional and local plans and shape the policies at lower levels of administrative organization.Williams (2003:125) considers that ”Planning, in its different forms, can be a mechanism for:

integrating tourism alongside other economic sectors;

shaping and controlling physical patterns of development;

conserving scarce or important resources;

providing frameworks for active promotion and marketing of destinations.”

As tourism sector has represented a significant weight in the western national economies, then this activity must be properly thought out so that its development can be sustained and sustainable. In pursuit of this objective, governments can play a central role in planning and managing the tourism development process at national scale. ForBaum & Szivas (2008:784) the way how is perceived the role of government and its agencies in to formulate policy, shape practice and deliver services is influenced by the political interpretation of the role of the state in the management of the economy and the social and cultural environment. Thus, in a destination the level of state intervention and direct engagement with the tourism sector that is found will depend upon the way is perceived the economic development, if it is based more on free market or planned models or their combination that are prevalent in the country at a particular point in time, a political construction that varies across time and place (Baum & Szivas, 2008:784). So, it is possible to find situations where the role of the government is more intervenient and others where its plans are more indicative.

According toWilliams (2003:135) national-level planning of tourism seeks to define primary goals for tourism development and identify policies and broad strategies for their implementation. According to this author usually national tourism plans reflects concerns over economic issues because of the perceived capacity of international tourism to affect positively a country’s balance of payments account and the capacity to create employment and that justifies why a growing number of nations have positioned tourism centrally within their national economic development plans.Williams (2003:135) refer that a second role for national tourism plans is the development of regions, to contribute for the redistribution of wealth and to narrow inter-regional disparities; to create employment; to channel tourism development into zones that possess appropriate attractions and infrastructure; to protect fragile regions from potentially adverse effects of tourism development as environmental factors.Williams (2003:135) also indicates a third focus of nationallevel tourism planning that is marketing, which is especially prominent amongst developed destinations that possess the expertise and the resources to form and promote a distinctive set of national tourism products.

Whatever the tourism development objectives, governments can use a varied set of planning instruments.Holden (2008:174) argues that although national priorities and global economic forces that derive from tourism development may detract from environmental conservation then governments have a range of policy and legislative measures (a mix of policy and planning measures) at their disposal which can be used to safeguard resources.Holden (2008:175) indicates some typical measures that governments can consider such as:

The establishment of protected areas through legislation, for example, national parks, and application for international recognition of significant environments, such as the World Heritage Site status given by UNESCO;

The implementation of land-use planning measures such as zoning, carrying capacity analysis, and limits of acceptable change to control development;

Mandatory use of environmental impact analysis for certain types of projects;

Encouraging co-ordination between government departments over the implementation of environmental policy and entering into dialogue with the private sector to encourage the adoption of environmental management policies, such as environmental auditing and the development of environmental management systems.

Tribe (2004: 382) also presents different approaches to encourage sustainability that includes different instruments:

Regulation – generally functions at the national and international level: Planning; Environmental impact assessment; Laws and regulation; Special status designation.

Market approaches – to influence the demand and supply of goods and services: Ownership; Taxes, subsidies and grants; Tradable rights and permits; Deposit–refund schemes; Product and service charges;

Soft tools – to influence consumption at the consumer level: Tourism eco-labelling; Certification/award schemes; Guidelines, treaties and agreements; Citizenship, education and advertising.

According toBenur & Bramwell (2015: 214) when working toward sustainable development and competitive advantage, destinations have fundamental strategic options, that is whether there is product concentration (one or few products) or diversification (diverse products). Also, they must think about their tourism product intensification, that is whether they develop niche or mass tourism products according to the desired market size and physical scale of development. The same authors refer that both strategies have potential advantages and disadvantages for business profitability, destination competitiveness and sustainable development and it is necessary for policy makers, planners, businesses and citizens to be aware and assess such potential advantages and disadvantages, and to consider them carefully in the specific context and circumstances of each destination.

On the last decades, an increase of domestic and international tourist arrivals and, at the same time, an increase on the supply of destinations allowed an increase of competitiveness on the marketplace on both the demand and supply side.Mariani et al. (2014:270) refer that, while competition among tourism destinations is increasing significantly, competitive advantage is typically sustained on a shorter and shorter span of time. Destinations increasingly need to adapt continuously to the changing tourist preferences and, at the same time, need to review if their image still reflects their strong points and credibility. This means a review of its strategies and its strategic positioning.

According toFyall (2019:271) the emergence of so many new destinations around the world brings the need for tools and techniques for destinations to maintain and/or increase their competitive position and their ability to be truly distinctive in the marketplace. This author argues that this is especially the case of many destinations that seek to position themselves beyond tourism goals as great places to live, work, invest and study as well as to visit.Fyall (2019:272) refers that for many destinations re-positioning represents an opportunity to rejuvenate and re-energize themselves with a change on its strategic approach. However, re-positioning strategy must be a campaign based upon real foundations and infrastructural change, tangible actions, to be believable and credible therefore, not to be superficial with words, images and logos not supported by actions (Fyall, 2019:281).

Mariani et al. (2016:4) refer that strategies in tourism became more complex due a tension between collaborative and competitive behaviours, a tendency that means that tourism destinations wherein competing tourism business have also to cooperate with the aim of marketing the destination and strengthening its brand image.Mariani et al. (2014:270) identified a trend that is the increasing importance of collaboration and especially coopetition (which is a mix of cooperation and competition), not only within a tourism destination, but also among destinations, as a strategy for a destination to achieve a competitive advantage in the long term.

The definition of strategies for the development of tourism destinations does not seem to be a consensual process anyway, it is a process that needs to be thought out and planned. Although the strategic tourism planning process is associated with a set of advantages and benefits, its implementation is not without constraints.Williams (2003:131) refers that there have been some constraints and weaknesses associated to tourism planning that includes a tendency towards short-termism (short-term perspectives limits the development of longer-term, strategic planning for tourism; reflection of the natural rhythm of annual cycles and consequence of the structure of the industry at most destinations and the dominance of small enterprises); organizational deficiencies (organizational shortcomings and an absence of planners with specialist knowledge of the industry); and problems of implementation (a divergence between what is intended by a tourism plan and what is actually delivered).

3. NATIONAL STRATEGIES FOR TOURISM IN PORTUGAL

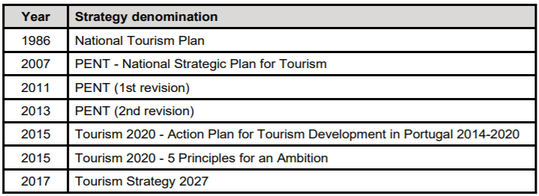

In Portugal tourism is considered a strategic sector of economic development because of its capacity for wealth-generation, contributing to GDP, to the balance of payments, to job creation, and consequently to the country’s competitiveness. Therefore, due to this importance, it is possible to find some national strategies for the development of the tourism sector with a strong commitment of government and tourism stakeholders. Despite that recent priority, it took time for the country to define a long-term major policy for tourism and to produce some planning instrument.Table 2 presents the major strategies for tourism in Portugal.

Moreira (2018) refers that in Portugal tourist planning was non-existent until the 1980s when the first National Tourism Plan (Plano Nacional de Turismo) was published in 1986. According toMoreira (2018): “Under this plan, 19 Regional Tourist Boards were created, following a policy approach to decentralize state power that saw some importance ascribed at both a local and regional scale; land-use planning was valued, as well as investments, professional training, tourist entertainment, balneology and spas and promotion aimed at diversifying markets and increasing revenues.”

From 2006 to 2015, the great reference and strategic orientation for the development of the tourism sector was the National Strategic Plan for Tourism (PENT - Plano Estratégico Nacional do Turismo) which defined the necessary actions for its sustained growth. The first version of PENT was approved by Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 53/2007, of April 4, and was developed for the 2006-2015 time horizon (Turismo de Portugal, 2013:4). Presenting the lines for the strategic development of tourism, PENT was structured in 5 axes: Territory, Destinations and Products; Brands and Markets; Qualification of Resources; Distribution and Marketing; Innovation and Knowledge (Turismo de Portugal, 2007:8); and its implementation required 11 projects, at various levels and encompassing multiple entities.

The main objective was the sustained growth above the European average, with a particular focus on revenue, translated into the following goal: annual growth in the number of international tourists above 5% and revenues above 9% (Turismo de Portugal, 2007:47). The objectives were then defined regionally for the 7 Portuguese regions (Porto and Norte, Centro, Lisbon, Alentejo, Algarve, Azores, Madeira). The strategy was based on the combination of (Turismo de Portugal, 2007:45):

The differentiating elements – these are tourism resources that distinguish Portugal from other competing destinations: climate and light; history, culture and tradition; hospitality; concentrated diversity;

The qualifying elements – these are necessary to qualify Portugal in the range of options for the tourists: modern authenticity, security and excellence in the relation quality/price.

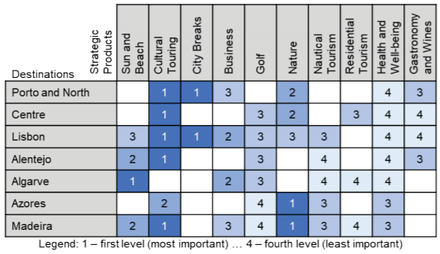

The strategy considered Portuguese “raw materials” – climatic conditions, natural and cultural resources. Ten strategic tourism products were defined for development and consolidation: Sun and Beaches, Cultural and Landscape Tourism, City Break, Business Tourism, Nature Tourism, Nautical Tourism (includes Cruises), Health and Wellness, Golf, Integrated Resorts and Residential Tourism, and Gastronomy and Wines (Turismo de Portugal, 2007:63). For each region a set of products that would contribute to its performance in the short/medium term were defined, according to the resources and distinctive factors of each one. The strategic product x destination matrix is presented onTable 3 and shows the contribution of different products to each region.

Source: adapted fromTurismo de Portugal (2015a:75)

PENT was then object of two revisions, the first in 2011 and the second in 2013. The last revision (Resolution of the Council of Ministers 24/2013 of April 16) was due to its need to be adapted to the strategic changes of the XIX government, due to the instability in the financial markets and moderate economic growth of the main tourist emitting economies of Portugal and also because the reality had shown that the definition of the objectives was not realistic because the results were far below the expectations (Turismo de Portugal, 2013:4). The 2013-2015 strategy continued to build on the 10 products defined in the PENT in order to reinforce the importance of supply stability in the external perception of destiny (Turismo de Portugal, 2013:14). To achieve the objectives, 8 development programs were defined, and 40 projects were implemented (Turismo de Portugal, 2013:48).

In 2015 Turismo de Portugal (National Tourism Authority) launched two strategic documents based on the 2020 time horizon: Tourism 2020 - Action Plan, intended at identifying priorities for the use of community funds for the 2014-2020 programming period; and Tourism 2020 - 5 Principles for an Ambition. Therefore, PENT was replaced by the Tourism 2020 Plan that defined the guiding principles of tourism public policies for 2016-2020. This plan is distinguished from the previous one by aiming at an ambition based on the private sector of tourism, an influence of the philosophy of the right-wing parties that constituted the XIXth constitutional government, which defined an ambition of competitiveness for Portugal and five principles that favour its concretization: the Person, Liberty, Openness, Knowledge and Collaboration (Turismo de Portugal, 2015a:4). Its objectives were to create conditions so that the revenues earned by the private tourism sector grow in Portugal above the average of its competitors and to be one of the ten most competitive destinations in the world (Turismo de Portugal, 2015a:4). The plan expressed this ambition in six different ways (Turismo de Portugal, 2015a:7-8):

A sustainable and quality destination;

A destination of competitive companies;

An entrepreneurial destination;

A destiny linked to the World;

A destination managed effectively;

A destination that marks.

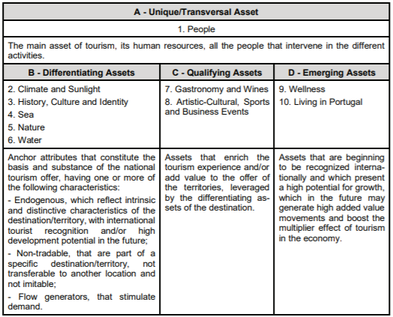

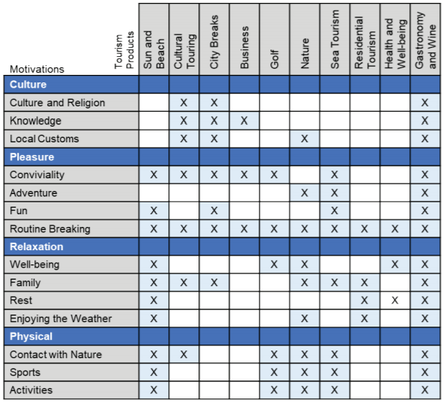

Another difference in this plan is the fact that it does not want to define strategic tourism products for each region, now focusing on the motivations and experiences to the detriment of the products, as can be seen inTable 4. So according to this plan: “Strategic will thus be any product that, in a sustainable and integrated way in the territory, can respond to tourist motivations through a sustainable business model.” (Turismo de Portugal, 2015a:59)

Source: adapted fromTurismo de Portugal (2015a:59)

Tourism 2020 - Action Plan consist on the strategic benchmark that establishes the objectives and the investment priorities in the area of tourism framed in the Portugal 2020, the European investment funds program of Portugal (Turismo de Portugal, 2015b). This plan follows the European Community programming cycle establishing goals and investment priorities and allocating the European structural and investment funds as a way of strengthening sectorial and territorial coordination. It provides a strategic frame of reference for the development of tourism by establishing its vision in a set of 5 strategic objectives (Turismo de Portugal, 2015b):

To attract – Qualification and valorisation of the territory and its distinctive touristic resources;

To compete – Reinforcement of the competitiveness and internationalization of tourism companies;

To train – Training and, R&D and innovation in tourism;

To communicate – Promotion and commercialization of the tourist offer of the country and the regions;

To cooperate – Strengthening international cooperation.

In 2017 the Tourism Strategy 2027 (Estratégia Turismo 2027 - ET27) was approved by the Resolution of Council of Ministers no. 134/2017 of September 27, which is, in the next decade, the strategic reference for Tourism in Portugal and the framework to follow the next cycle of Community Programming. The construction of the Strategy for Tourism 2027 was based on a participatory process, broad and creative, in which the State assumes its responsibility and mobilizes the various agents and society. It establishes a long-term vision, combined with action in the short term, allowing stakeholders to act with greater strategic sense in the present and to frame the future community support framework 2021-2027.

The ET27 is a long-term shared strategy for Tourism in Portugal that aims at the following objectives (Turismo de Portugal, 2017:10):

To provide a 10-year strategic framework for national tourism;

To ensure stability and commitment on strategic options for national tourism;

To promote integration of sectoral policies;

To generate a continuous articulation between the various agents of Tourism;

To act with strategic sense in the present and in the short/medium term.

The implementation and materialization of the ET27 goes through the implementation of projects, based on the lines of action of its 5 strategic axes (Turismo de Portugal, 2017:50):

To value the territory and the communities;

To boost the economy;

To enhance knowledge;

To generate networks and connectivity;

To project Portugal;

And it is committed to goals of economic, social and environmental sustainability.

This is a strategy focused on 10 assets that aim at the sustainability and competitiveness of the Portugal destination distributed in 4 categories of strategic assets (Turismo de Portugal, 2017:46).Table 5 presents the 10 strategic assets that aim the sustainability and competitiveness of the destination.

Beyond the referred strategic plans, it should be noted that in Portugal tourism is also subject to a set of spatial planning instruments (territorial plans and programs that compose the Portuguese Territorial Management System which establishes in different levels (national, regional and municipal) the objectives, principles and responsibilities for spatial and urban planning 1) and other legal framework (as the Fundamental Network for Nature Conservation 2) that affect its development and which implies a diversity of actors, decision-making powers, private and public interests that is not always easy to reconcile and to coordinate. Tourism is included in a first level in the sectoral policy instruments with territorial impact and in connection with the other territorial management instruments. Therefore, in the regional plans, municipal plans and in the special plans must be identified the location and distribution of the touristic activities and spaces and legal restrictions related to the use of natural resources, land-use among others that affect touristic activities.

In any case, the number and diversity of plans and legal framework with influence on touristic activity has not always been positive, sometimes ending in a complex normative of difficult coordination and articulation between sectoral and territorial scope. According to Machado (2010:58) the institutional history of the Portuguese tourist development reveals difficulties in the cross between sectorial tourism policy and territorial planning and urbanism, leading to the insufficiency and ineffectiveness of political options of touristic spatial planning.

4. MAIN RESULTS AND CHALLENGES FOR TOURISM IN PORTUGAL

Almost 15 years after the first major strategic plan for tourism development in Portugal, and 5 years after the Tourism 2020 Plan, it is important to look at the current situation and see how tourism has evolved and how it contributes to the economic development of the country today.

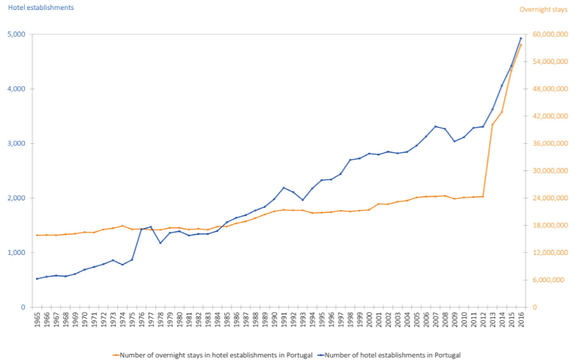

Looking as far back as the middle of the XXth century (Graph 1), we see that Portugal has come a long way. According toMoreira (2018), during the 1960s the expansion of commercial flights to Portugal let to the tripling of the accommodation capacity, in order to serve this increase on the demand. After some fluctuation in the 1970s, due to the oil crisis, but also to the 1974 revolution, the country joined the European Economic Community in 1986, and the investment in infrastructure led to the improvement of supply which, in turn, was reflected in an increase of overnight stays.

Source:Moreira (2018)

After 2012 the number of overnight stays boosted. On one hand, this was because of changes in the regulation of some types of accommodation, that facilitated the opening of new establishments. On the other hand, several international events turned Portugal in to an interesting alternative to some Mediterranean destinations with security issues. Lastly this boost may also be attributed to the effects of the previously identified strategic planning instruments which, together with the international promotion of the destination and international awards received, pushed the growth of demand upwards.

Looking at the Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) data, from the National Statistics Board (Instituto Nacional de Estatística - INE, 2018), we find that the Gross Value Added (GVA) generated by tourism activities in Portugal rose 6,6% in 2016 and 13,6% in 2017, accounting for 7,5% of the national GVA in 2017. The national economy GVA only rose 4% in the same period, so this reflects the activity’s importance to the country’s economy.

The World Travel & Tourism Council data for Portugal (WTTC, 2018), shows that tourism accounted for 10,2% of the investment made in 2017 and 8,5% of the existing employment is in tourism activities, a figure that rises to more than 20,4% if indirect and induced effects are also accounted for. The TSA data indicates that tourism activities accounted for 9,4% of the national employment in 2017, which represents an increase of 4,8% relative to the previous year, a figure higher than the national employment evolution, that only rose 2,1%.

Considering the information made available byPordata (2019), in 2018, the tourism sector generated 328,5 thousand jobs (weighting 6,7% in the national economy), representing an increase of 5,3 thousand jobs compared to the year 2017. The tourism sector is the largest economic activity in the country, accounting for 51,5% of exports of services and 18,6% of total exports in 2018, with tourism revenues accounting for 8,2% of Portuguese GDP.

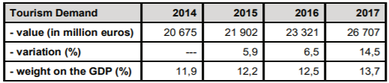

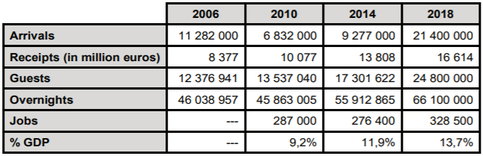

The main results from the TSA (INE, 2018) are presented inTable 6. As we can see, the tourism demand, measured by the tourism consumption on the economic territory (which includes accommodation, food and beverage, transportation, travel agencies, leisure and recreation and other services) has been raising consistently, both in figure and in its weight on the GDP.

According to theEuropean Travel Commission (2019), up until July, the data for 2019 showed a positive performance for the European tourism sector following the solid performance in 2018. Portugal grew both in number of arrivals and in overnights, benefitting significantly from increasing year-on-year tourism revenues. Although competing destinations, like Turkey, Greece or Cyprus, had strong performances, that didn’t lead to a decrease in the demand for Portugal.

Table 7, shows the evolution of the main indicators commonly used. These figures confirm that, although there was a period of recession that started after the 2007 international crises, which reflects on the numbers for 2010, tourism has been able to power the Portuguese economy forward. Even during the intervention of the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Union (commonly called the “troika”), between 2011 and 2014, most of these indicators recovered, having continued to grow after the “clean exit” of the “troika”. The tourism demand amounted to 13,7% of the GDP in 2017, a growth of 14,5% in relation to the previous year.

Source: UNWTO (2007,2011,2015),WTTC (2018),Pordata (2019)

Tourism in Portugal ended 2018 with indicators growing. There were 24,8 million guests registered, a growth of 3,8% over 2017. Among these, 15 million were foreign guests. With a total of 66,1 million overnight stays in 2018 (46,5 million overnight stays by foreigners and 19,6 million overnight stays by nationals), the main emitting markets for Portugal were the United Kingdom (9,1 millions), Germany (6,2 millions) and Spain (4,8 millions) (Turismo de Portugal, 2019).

The increases were also reflected in revenues, with a growth of 9,6%, corresponding to 16,6 billion euros. In this indicator, the main issuing markets for Portugal were the United Kingdom (2,8 billion €), France (2,7 billion €) and Spain (2,2 billion €) (Turismo de Portugal, 2019).

The results presented above reveal the capacity of Portuguese tourism to generate more revenue, more employment and to extend more and more the activity throughout the year and the territory and, therefore, that tourism has the capacity to be a sustainable activity all through the year, not only during the “high season” months.

4. 1 Challenges for the future

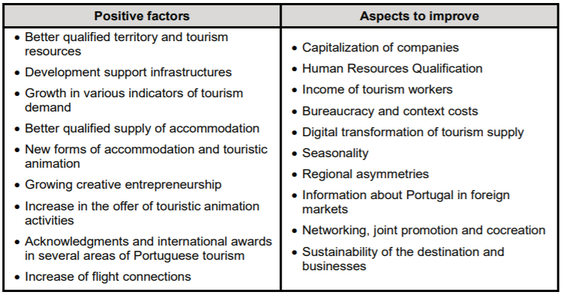

In the new Strategy for Tourism 2027, Turismo de Portugal identifies the positive factors of a decade (2005-2015) of tourism strategies and the aspects to improve in the future. These are presented inTable 8.

Analysing the decade, it was possible to see that the several projects implemented on the sequence of the national strategies had positive effects in developing the tourism supply and infrastructures, like the accommodations. But there are also many areas to improve, as the human resources qualifications, competitiveness of companies, bureaucracy, regional asymmetries, among other aspects that consist on challenges for the future. Thus,Turismo de Portugal (2017:38) pinpoints the 10 challenges for a 10-year strategy, which are:

People – To promote employment, qualification and the valuing of people and to increase the income of tourism professionals.

Cohesion – To extend tourism to the whole territory and to promote tourism as a factor of social cohesion.

Growth in Value – To achieve an accelerated rhythm of growth in revenue vs. overnights.

Tourism All Year – To extend the tourism activity throughout the year, so that tourism is sustainable.

Accessibilities – To ensure the competitiveness of accessibilities to Portugal as a destination and to promote mobility within the territory.

Demand – To reach the markets that best respond to the challenges of growing in value and that allow to extend the tourism to the whole year and in the whole territory.

Innovation – To stimulate innovation and entrepreneurship.

Sustainability – To ensure the preservation and the sustainable economic valuation of cultural and natural heritage and local identity as strategic assets, as well as to make this activity compatible with the permanence of the local community.

Simplification – To simplify legislation and streamline administration.

Investment – To Ensure financial resources and to promote investment.

According toLuís Araújo (2019), president of Turismo de Portugal, one of the objectives of the Tourism Strategy 2027 is “to affirm Tourism as a hub for economic, social and environmental development throughout the territory, positioning Portugal as one of the most competitive and sustainable tourist destinations in the world”.

To achieve this goal, and address the 10 challenges identified above, several measures have been defined, which include investment in technology, infrastructure and human resources. To this end, specific financing lines have been set up to promote the development of inland tourism and instruments that enable the mobilization of tourist businesses and public entities to ensure a more sustainable, affordable and inclusive tourism offer.

Taking in consideration the megatrends thatWTTC (2019) identified as having implications for the travel and tourism industry, we can understand more clearly some of the challenges for the Portuguese tourism.

Related with the innovation challenge, the Reality Enhanced and the Data Revolutionised megatrends imply that tourism activities need to be more experience driven. This can be made possible by the easy access to information and the use of big data and IoT in today’s world, that allows a better personalization of tourism products.

Related with the people and with the cohesion challenges, the Life Restructured and the Power Redistributed megatrends imply that the activity has to take in consideration all the recent social changes, not only in terms of local communities, workers and business models, but also in terms of demand and what tourists value. Individuals are becoming increasingly more mobile and are demanding more accountability from tourist companies.

Related with the demand and the sustainability challenges, the Consumption Reimagined megatrend reflects the growing importance of environmental awareness, but also social and economical concerns of younger generations. Destinations must take these aspects in consideration or face the risk of losing important niches of demand.

Regarding Portugal, these megatrends are, somewhat, already embedded in the challenges identified. All the policies that have been adopted, in recent years, have addressed most of these trends and have proven to bring positive effects. Nevertheless, there is an acknowledgment of aspects to improve, and all the stakeholders have been working together to face these challenges, in order to promote the county’s economic and social development.

5. CONCLUSION

The development of touristic destinations implies the analysis of competitiveness factors and assessment of potential impacts involving the definition and implementation of strategies that comprises a complete, careful and meticulous planning and promotion process. Strategic planning in tourism is crucial because it allows the maximization of income from this activity and, the minimizing of its negative effects and in the long term, the sustained development of the touristic destination. Therefore, national-level planning of tourism seeks, in many countries, to identify a set of objectives that intend to develop this sector trough the definition of strategies and policies that could fulfil that intent.

In Portugal the strategic importance that this sector has in the economy has long been perceived, due to its capacity for wealth-generation, job-creation and contribution to the country’s competitiveness and cohesion. So, a set of strategies for its development have been developed. This paper presented the main national strategic instruments that have been guiding the development of tourism in Portugal analysing its objectives and ways of implementation.

From all the references, PENT proved to be the first major strategy for the sector occupying the horizon of a decade. Although it has been replaced by other strategies, these still contain some aspects of this plan, both in the objectives and at the level of the strategic products / resources / assets to be further developed.

The major indicators analysed show that the strategies had positive effects to develop the touristic supply and infrastructures, as accommodations. Worthy of mention is also the merit of tourism companies, which have improved its qualification, competitiveness and modernization. However, there are many areas to improve as the human resources qualifications, competitiveness of companies, bureaucracy, regional asymmetries, among other aspects that consist on challenges for the future. These aspects to improve and challenges are directly related to the megatrends identified by the WTTC, which focus on the tourists, their needs and their power, but also on the technologies and the ways they can be used to process information and respond to the consumer’s needs.

Despite the efforts of the Government and tourism stakeholders that have recently made a stronger commitment to develop this sector, it must be taken into account that tourism is subject to a quantity of plans and legal framework that affect its development, which implies a diversity of actors, decision-making powers, private and public interests that are not always easy to reconcile and to coordinate.

This paper presented an analysis of Portuguese strategic planning instruments in the area of tourism and explored the main indicators for tourism development, trying to assess the major benefits that resulted from the implementation of these instruments. The main challenges for the Portuguese tourism and the areas that still need further improvement were also identified.

The limitations of this paper are related to the fact it is focused only in Portugal. As a future work, it would be important to compare the results obtained in Portugal to the ones obtained in other markets with similar characteristics and that have also implemented national tourism plans. This benchmarking would, surely, highlight new aspects to be taken in consideration in future plans.