INTRODUCTION

Culture (lat. colere – cultivate, nurture) is an integrated system of attitudes, beliefs and patterns of behaviour that are characteristic of members of society, and are not a result of biological heritage, but a social product that is created, transmitted and maintained through communication and learning. Culture is by its very nature a social and psychological product because human nature a political being, a “zoonpoliticon” as Aristotle puts it, a community being, a social being[1].

Alcohol consumption is as old as humanity, archaeological findings suggest that, as early as 30 000 years ago, humans knew that fermentation could produce alcoholic beverages[2]. Beer was known in ancient Egypt for 5 000 years BC and was drunk mostly by the poorer population, while the wealthy drank wine. In India, beverages were made from rice (surah) 3 000 years ago, and in Greece, mead was produced. Before the new era, people made wine, and the first description of distillation dates back to 800 AD (the Arab invention). The first descriptions and warnings about the harmfulness of excessive drinking were found in written documents from ancient Babylon, Egypt, Greece and Rome. The Greek god of wine was Dionysus, and the Roman god of wine was Bakus. The Bible says that Jesus created wine from water, and the Church preached that “wine is the blood of Jesus”. Wine is still used in Christian rituals today[3].

Alcohol has been used in the past as a medicine or foodstuff, as a means of relaxing, warming or sleeping, as an integral part of social rituals and celebrations. Among orthodox Jews, alcohol is used as a ritual drink, but it plays no role in daily consumption, while in Italy and France alcohol is a foodstuff, and intoxication is condemned.

Customs, habits, intensity of consumption, type of alcoholic beverages, differences in alcohol consumption by gender, age, religious affiliation differ from culture to culture. Numerous sociological studies address the influence of religious beliefs, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages is linked to a number of factors, one of which is the degree of religiosity of the population. The influence of religious beliefs on alcohol consumption to alcohol consumption in a country varies and depends on many factors, including the degree of religiosity of the population. A significant correlation between alcohol consumption and religion is evident in Islamic law-enforced countries where alcohol and alcohol consumption are prohibited, and in the case of Judaism that permits alcohol consumption, however, the rate of alcoholism among the Jewish is extremely low. Jewish people are specific in terms of alcohol consumption because research shows that 90 % of the Jewish consume alcohol, but the rate of alcoholism is extremely low[4]. Christianity has different views on alcohol consumption; Roman Catholic, Eastern Protestant, and some Protestant churches allow moderate alcohol consumption, while some churches impose abstinence from alcohol, such as the Baptist, Methodist, and some Protestant churches.

R. Bales divides alcoholic beverages according to their function, citing a religious, ceremonial, hedonistic and utilitarian function which addresses certain needs such as relieving oneself from weakness, oblivion, hunger, in the function of warming and repelling fatigue and recall sleep. The hedonistic function refers to the need for feasting and euphoria[4].

D.J. Pittman classified cultures according to their attitude to drinking. He thus distinguishes four basic types of cultures: the first are cultures that condemn the use of alcoholic beverages in any form (Muslims, Hindus, and ascetic Protestants), the latter are ambivalent cultures in which a negative attitude towards alcohol coexists with the idealization of intoxication (English speaking countries, Scandinavia)[5]. Third are tolerant cultures that tolerate moderate alcohol consumption but condemn drunkenness (the Jewish and Italians). Over tolerant cultures are the fourth in which very indulgent attitudes toward intoxication and drunkenness are widespread (French, Japanese, and Camba culture in eastern Bolivia).

From an ethnic standpoint, Štifanić describes completely abstinent peoples such as Arabs, then nations with a low incidence of alcoholism as the Jewish, and those with a high incidence of alcoholism as Irish, Scandinavians, Russians, Slovenes, and Croats. According to the same author, sociology explains five basic approaches that deal with the problem of alcoholism: a functionalist, socio-cultural, sociographic, symbolic-interactionist, and social-political approach[4]. The sociocultural approach addresses the historical aspects of alcohol consumption, examines the ways in which individual societies approach the problem of alcohol consumption, and the meanings that alcohol consumption has in a particular society. Drinking alcohol has the function of enhancing social cohesion; Alcohol consumption rituals symbolize the closeness and solidarity of social groups, and also serve to signify a change in status at birth, wedding, funeral and similar ceremonies where alcohol drinking is inevitable in many societies.

Drinking patterns and types of alcoholic beverages differ from culture to culture as well as between different social strata, but they also have many common characteristics that allow us to distinguish several different patterns of consumption across Europe.

The Mediterranean drinking pattern is typical of the European Mediterranean, and is characterized by excessive drinking without intoxication, socially unobtrusive drinking and tolerating excessive drinking. The alcoholic beverage that is most consumed is wine, which is why the countries of the European Mediterranean are classified in the so-called wine zone (Spain, Portugal, Italy, France, Montenegro, Macedonia and others). This drinking pattern is based on frequent consumption of alcohol, but without the loss of control over drinking. Alcohol is consumed in small quantities, but throughout the day, usually with meals. In the countries of the European Mediterranean, a tolerant attitude towards alcohol consumption is present, drinking is advocated and tolerated, but heavy alcoholism is still condemned. Due to the most frequent consumption of beer, the countries of Central Europe are classified in the beer belt, and they have an ambivalent attitude towards alcohol consumption, i.e. in some situations they advocate drinking and in some of them they prohibit and condemn it (Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland). Northern Europe as well as the Slavic peoples have a highly tolerant attitude towards alcohol consumption. Drinking is advocated, drinking is allowed at every social occasion, and even heavy drinking is tolerated. Spirits are being drunk, and the vodka/brandy belt includes the Nordic and Baltic states, Poland, Ukraine, Russia and Belarus.[6].

ALCOHOLISM AS A SOCIAL PROBLEM

T. Troter pointed out 200 years ago that he considered alcoholism a disease. In the 19th century, M. Huss considered alcoholism a disease[7].

The definition of drinking alcohol as a deviant behaviour, together with the definition of this problem in medical terms and the identification of adverse effects, began only in the 19th century, with changes in the conception of personality and the concept of addiction. From the 1960s onwards, anthropology began to free the drinking of the shackles of human pathological and deviant behaviour and began to view it as a social act, and since the 1970s, anthropology has described and developed a view that drinking alcohol in most cultures is a feature of festivities in which drinking, even excessive, is implied and considered normal[8].

Clinical practice and numerous studies of alcohol abuse in recent decades show that alcoholism is associated with psychiatric disorders and criminogenic behaviour, and knowledge of the personality of each alcoholic is a necessary precondition for therapy. Alcoholics change their personality over time. They only start worrying about the supply and consumption of alcohol. They lose the interests they had before, they do not care about family and work. They become indifferent, aggressive and overly irritable, and alcohol becomes a shield to defend against the demands of reality. The ability to concentrate and think straight disappears. Abulia occurs, gratification is missing, new information is difficult to grasp, and old information is lost. Ultimately, they come to the stages of disinhibition, their reactions become impulsive, they insult and abuse others. Neglecting body hygiene is also commonly reported. Personality changes are added to already existing imbalanced personality traits[9]. Žarković Palijan in her doctoral dissertation states that psychodynamic tests have been used in many researches of alcoholics personality, the results of which mostly show that alcoholics are more often characterized by schizoidness, masochistic reactions, passivity, poor organization of the ego, ambivalence and a vague concept of self, impulsivity, low tolerance for frustration, satisfaction with short-term rewarding, difficulty in establishing adequate object relationships, sexual identity problems, and negative self-conceptions[10]. Despite some similarities, alcoholics show marked differences in the way these lines manifest themselves. The author concludes that, while it is important to know some of the general facts and common characteristics of alcoholics, it is even more important for the clinical practice to know the differences between them, which allows a more appropriate approach to each individual patient as a unique personality.

What is needed in this situation is a truly broad theoretical framework within which each individual can be placed, and from that frame, practical procedures that represent the basis of the treatment, are derived. She also points out that alcoholism is difficult to treat according to theorists, precisely because of its deep oral fixation and the difficulty in establishing transfers due to rigid defences. Antisocial personality disorder is often associated with alcoholism, and the typology of alcoholics is also based on the difference between alcoholics with antisocial personality disorder and those without antisocial personality disorder. It has been established that alcoholics with antisocial personality disorder start drinking alcohol earlier and show faster development towards more severe alcoholism[10]. Most psychoanalysts believe that the cause of alcoholism happens because of the multitude of specific failures in emotional development and because of the circumstances in the family. The earlier the psychobiological development at which the individual stopped, the more immature his behaviour, personality and defence mechanisms were. The more severe his drinking problem was if he became an alcoholic, the poorer his prognosis was. Alcoholism is socially manifested mostly in the workplace and in the family.

Alcoholism is easier to hide in the workplace, so it first manifests in the family in the form of a loss of family cohesion. It is often the children who suffer the most from neglect of family and parenting responsibilities[11]. Results of two longitudinal (US) studies examining the impact of father’s alcohol use on childhood development, the Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS), which monitored a sample of alcoholic families with 3-5-year-old children over a 20 year period and the Buffalo Longitudinal Study (BLS), which monitored a sample of alcoholic and non-alcoholic families starting from a child’s age at 12 months, independently provided evidence that alcoholic fathers directly and indirectly had negative influence on the social-emotional and cognitive development of their very young children. Alcoholism of the fathers alone or in combination with simultaneous psychopathy (the most common antisocial behaviour) can lead to psychopathology in children as early as infancy. Parental alcoholism has been characterized as a family stressor and a reason for parental neglect of children[12].

Alcoholism is an important socio-economic problem in modern society, since it can result in the loss of human lives, increased costs of treatment, loss of manpower and increased crime. In their study, Coeteti, Ion et al. analysed the factors that may determine or facilitate the intergenerational transmission of alcoholism, and the results showed that the mechanisms of intergenerational transmission of alcohol consumption and consumption patterns are complex, determined by a number of factors including both genetic and family factors. Children of alcoholics have a statistically increased risk of alcohol and other substance abuse, with paternal alcoholism as the dominant factor in predicting offspring alcohol dependence[13].

The results of a study conducted by Nastasić and his associates in 1998 on 60 married couples where the husband (father) is an alcoholic showed that the majority of alcoholics (58 %) have a positive history of alcoholism in the family, while their wives’ percentage is lower (40 %), and that alcoholism and marriage begin almost simultaneously in at least 60 % of cases, i.e. the average duration of marriage without alcoholism by about 40 % is barely three years. The authors also point out that research data indicate that alcoholism becomes apparent at the very beginning of marriage, so it seems that personality traits associated with alcoholism have an impact on the choice of spouses, that alcoholism interferes with family life at an early stage of maturation and family development, and that most families report seeking treatment at time when the middle stage of matriculation normally takes place, i.e. in a phase when regulatory processes have already been formed, so they are already significantly (pathologically) stabilized due to the presence of alcoholism (about 10 – 11 years). Significant is also the fact that 81,1 % of children are less than 15 years old at the time of starting their parents’ treatment, which means that their psychosexual development is hindered very early, in the most favourable combination it starts at 4,5-5 years, but in most cases even earlier (from birth or at 2-3 years)[14].

Considering the quality and characteristics of the process of transgenerational transmission in the family of the alcoholic husband, Nastasić states that the families of the alcoholic husband are characterized by a straight-line progression, i.e. a permanent slight increase of the fusion indicator from generation to generation, which means that emotional events in each successive generation will be characterized by an increasing degree fusions in relationships and an increasing number of dysfunctions and symptoms. It has also been observed that the transfer in the families of women whose father is not an alcoholic differs from the transfer in the families of those women whose father was an alcoholic, which depends on the length of the interval of trust. The intergenerational transfer of alcoholism takes place according to Orford, Velleman and Nastasić, through a positive relationship with a single parent or through a deficient relationship with one of the parents, i.e. the choice of partner may be affected by the repetition of the pattern of parental alcoholism or the repetition of the pattern of behaviour of the other parent, which subsequently leads to choosing/marrying an alcoholic[14].

From the above, the author also explains the more socially accepted drinking of men, because they have less emotional burden of their father’s drinking, while experiencing their own drinking with less feelings of threat and guilt, they may even experience it positively. A group of authors (Hoel, Magne, Erikson, Breidablik, Meland) in their 2004 article prove that excessive drinking is a very important factor of social acceptance in the adolescent population. In contrast, abstinence and drinking small amounts of alcohol are associated with better psychological and emotional health. Excessive drinking also leads to increased problems in the family and at school. Adolescents who are more attached to family are more likely to be abstinent. Early onset of excessive drinking in adolescence is an indicator of poor mental health, and later onset, especially in young men, suggests mental problems and difficulties in adopting adult behavioural patterns. Getting into the world of drinking too early in both young men and girls is an indicator of mental problems[15].

Social compulsion to drink alcohol has evolved into such a psychological power today that people who do not drink (abstinent people) do not have the courage to refuse alcohol when offered because they are afraid to oppose existing social customs. In addition, young people want to go through the puberty phase as soon as possible and become adults. And they see the fastest way to this in precisely the forms of behaviour that they were always forbidden when they were children, and parents and other parents were allowed to do so. That is why young people try to express their “adulthood” and their entry into the adult world by consuming prohibited means[16].

The incidence of substance abuse or dependence between relatives of first-born alcoholics is 44 %, of which 80 % is related to alcohol abuse or dependence[17].

ALCOHOLISM AND COMORBID DISORDERS

Alcohol-related disorders are widespread. It is estimated that only 10 % of the world’s population has never drunk alcohol. There are different data on the number of alcohol addicts – generally ranging from 5-8 %. About as many people drink at the abuse level. In Croatia, 7 000 alcoholics are treated for the first time for alcoholism, but the number of hospitalizations is much higher, which tells us that recurrence is very common and that post-hospital care is still poor or underdeveloped[7].

Taking comorbidity into account significantly contributes to the quality and success of alcoholics’ treatment and improves prognosis. The study of comorbidity has been enhanced by the use of standardized psych diagnostic instruments, as well as diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of primary and secondary psychiatric disorders set out in DSM-IV-TR and MKB 10. In approximately 37 % of cases, alcoholics are diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders that may be primary (promote drinking and alcohol addiction), secondary (develop as a result of alcoholism), or may occur at the same time as addiction. Dependence is known for “self-healing”, that is, alleviating insomnia, anxiety and depression. Primary or comorbid psychiatric disorders occur before drinking or while drinking. Comorbid disorders can stimulate drinking, hide drinking problems, contribute to alcohol dependence, which ultimately complicates diagnostic procedures and treatment. Secondary psychiatric disorders are diagnosed if symptoms of a psychiatric disorder develop during intoxication or within one month after intoxication or onset of abstinence and cause clinically significant difficulties with regard to work, family and social functioning. In clinical work, it is very difficult to distinguish primary from secondary psychiatric disorders, so it takes two to four weeks of abstinence to evaluate[18]. Psychiatric disorders related to alcohol dependence are: anxiety, Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, concomitant alcohol and drug addiction, pathological jealousy, aggression, states associated with brain damage[19]. The rule is that comorbid psychiatric disorders are treated concurrently with treatment of alcohol abuse[18].

Abuse and alcohol addiction in women have been steadily increasing in recent decades. The question of why this is so, and the answer are to be found within a sudden change in the role and position of women in society in the last century. Thaller et al. state that excessive drinking and alcohol addiction in women is proportional to the degree of freedom, women’s emancipation and employment[19]. Women have fought for many rights and equality in almost all walks of life in a relatively short period of time, but they have also received many new commitments, while maintaining all the old ones. Today, in addition to her traditional roles in the family, as a mother and wife, a woman also has her vocation, which requires a lot of work, effort and proving oneself. The constant desire to satisfy and be “perfect” in all areas of life is a source of constant tension, insecurity, fears and frustrations.

The way out was to drink alcoholic beverages which, through its anxiolytic action, provide temporary relief and escape from reality. The societal tolerance of moderate alcohol consumption has only further enhanced such choices, putting the woman at risk of sinking deeper and deeper towards alcoholism, because over time, only by increasing the amount of alcohol will it have the same effect. From everything previously stated, we can conclude that the increase in women’s drinking is a rare negative consequence of emancipation[19].

This is confirmed by the findings of about fifty years ago, which stated that the ratio of male alcoholics to female alcoholics was about 1:10, and twenty years ago 1:7. Over the last ten years, epidemiological studies show that women are drinking more and that the ratio of male alcoholics to female alcoholics is around 1:3,5 today[19].

Interesting are the results of a multi-national study conducted in 13 European and 2 non European countries that examined the differences in drinking between women and men. In the introductory article, Bloomfield, Gmel and Wilsnack state that the gender difference in alcohol consumption is one of the few universal gender differences in human social behaviour[20]. However, the magnitude of these differences varies greatly from one society to another. The results show that the higher the gender equality in a country, the smaller the differences in sexual behaviour in drinking. In most analyses, the lowest gender differences in drinking behaviour were found in the Nordic countries, followed by the western and central European countries, and the largest gender differences in countries with developing economies.

Although alcoholism in women is mostly symptomatic, the socially permissible amount of alcohol in women is increasing, which may affect the development of primary (male) alcoholism. Many studies attribute the worrying increase in alcoholism in women to the primary or male (social) type of alcoholism, which is increasingly occurring in working women[21].

Some of the risk factors that lead to excessive drinking in women are the same as in men, such as: hyperactivity, psychopathic personality, spouse or drinking friend, genetic load, but with the emphasis that all these factors, except hyperactivity more prevalent in women who drink excessively than in men[22].

Women start drinking excess alcohol at a later age. Although they start drinking later, women perish faster than men, and develop addiction and socially intoxicated alcohol addiction more quickly. Women who drink, drink significantly less alcohol than men who drink. Their partner is also very likely to drink excessively. In addition to the diagnosis of alcohol addiction, they have other psychiatric diagnoses, and in addition to alcohol, they abuse other psychopharmaceuticals. Drinking largely causes and deepens depressive disorders and vice versa, and for this reason over-drinking women are more prone to suicide. They are often adults or in families of drinking, and are often victims of physical or sexual violence. Their episodes of excessive drinking are generally associated with some stressful event. The mortality rate of women who drink excessively is higher than that of men who drink excessively[23]. The results of a study conducted in 2011 indicated some interesting points regarding differences in family characteristics and psychosocial development characteristics between female and male drug addicts show that, with regard to the sociodemographic status of the primary family, female addicts are more likely to come from families with better material status of excellent and very good status (women 31 %, men 12 %), unlike men who most often come from families of good status (men 70 %, women 57 %), and are more frequent in order births of the first and only family member (68 % female, 43 % male)[24].

Furthermore, the results show that female addicts statistically differ significantly in their emotional relationship and communication with their mother in childhood and adolescence, and that female addicts perceive their relationship with their mother more negatively than men, and more often describe their communication with their mother as defensive and critical. However, with regard to emotional relationship and communication with the father, which is generally negative for both men and women addicted, there is no statistically significant difference, although women perceive their relationship with their father somewhat more negatively than men (40 % women, 34 % men ), and men perceive their communication with their father as somewhat more defensive than women (women 53 %, men 64 %)[24]. Although the study was conducted on a sample of drug addicts, these characteristics of emotional relationships and psychosocial development are observed in clinical practice in alcohol addicts as well. Suicide rates in the northern counties of Croatia are higher than in the southern counties, and alcoholism is known to be a risk factor for suicidal behaviour. Brečić states that 20-50 % of suicide victims are alcohol addicts, i.e. 30-80 % of suicide victims were intoxicated at the time of suicide[25].

According to the data provided by the Croatian Institute of Public Health, age-standardized rates of suicide deaths in Croatia for all ages and ages up to 64 show fluctuations until 1997, and since 1998 there has been a fall in rates (in 2016, the rate of 13,2/100 000 for all ages and 10,9/100 000 for ages 64 and up). For ages 65 and older, the rate, with more pronounced fluctuations, has also declined substantially since 1998 (in 2016, the rate was 31,3/100 000)[26].

According to other Croatian authors, a significant progression of suicide among youth has been observed in our country, especially after the Homeland War. According to data from the past 10 years, an average of 56 children and young people have committed suicide in Croatia annually, which may be related to the occurrence of more frequent consumption of alcoholic beverages by young people, which begins at an earlier age[27]. There are differences in age-standardized rates among Croatian counties. Counties in the coastal part of Croatia have lower rates of suicides than individual continental counties[28].

Addiction has become a major problem in modern society, as evidenced by the 2009 World Drug Report[29]. Although this report concerns psychoactive drugs, not alcohol, the effects of consumption and prevention can be applied to all forms of addiction, including alcohol. The report states: “The problem of drug addiction is a global health and social problem of the modern world, which is essentially a drama for all those involved, especially for a family that is often faced with the inability to successfully confront the problem. The increasing prevalence of drug abuse is consequently leading to the crisis of modern society, the crisis of the family, endangering fundamental societal values and the rise of crime”[29].

DIFFERENCES IN ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION BY REGION

The study, based on data from the 2003 Croatian Health Survey by Benčević-Striehl, Malatestinić and Vuletić, aimed to assess regional and gender differences in the prevalence of alcohol abuse in Croatia. The results of the study indicated that the highest prevalence of alcohol consumption in men was observed in eastern Croatia (14,1 %), which also recorded the lowest prevalence of alcoholic beverages (0,3 %). The highest proportion of women who reported drinking alcohol was recorded in northern Croatia (1,5 %)[30]. The results show the expected gender gap in alcohol consumption. This underscores the potential, but underutilization, of primary prevention and health promotion with particular emphasis on regional customs[30].

In Croatia, according to estimates by Mustajbegović et al., 2 260 540 people drink alcohol, 11 330 351 men and 930 196 women[31]. From this, we can see that 81,3 % of the male population drinks, while the percentage of women is 51,2 %. The frequency of alcohol drinking by counties in Croatia is also indicated. Data from the analysis of the mentioned authors showed that most alcohol is drunk in the Varaždin and Koprivnica-Križevci counties, as well as the Istrian and Šibenik-Knin counties, more than 65 %. At least 30 % of alcohol is drunk in the County of Lika-Senj. In the Lika-Senj County, 85 % are predominantly men, and women predominate in Virovitica-Posavina County with more than 50 %. The county with the same number of men and women who drink alcohol is Varaždin. The majority of alcohol is drunk by the 35-64 age group, but there is also a shift to the younger generations up to 34 years, especially in Vukovar-Srijem, Brod-Posavina and Koprivnica-Križevci counties. People drink all alcoholic beverages, but mostly wine and water, followed by beer. The amount of drinking is analysed in glasses. People mostly drink a combination of wine and water (bevanda, spritzer) in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, above 8 glasses. This is followed by the County of Šibenik-Knin with about 7 glasses and the County of Krapina with about 4 glasses. The combination of wine and water is being followed by beer consumption, mostly in the County of Lika-Senj with more than 4 glasses. In the County of Lika-Senj, people drink mostly spirits, with about 3 glasses. In the City of Zagreb and the County of Karlovac, people equally drink beer and the combination of wine and water (spritzer)[31].

CULTURAL FEATURES OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION IN CROATIA

Alcohol consumption in Croatia is a socially accepted behaviour, and society has a high tolerance for drinking alcohol as a cultural pattern and an accepted style of behaviour deeply rooted in customs. Drinking alcohol is favoured even when the consequences of alcohol dependence on health, family and work function are evident. The norms of behaviour are such that drinking alcohol is also expected even when a person does not want to drink alcohol, out of respect for those who celebrate, grieve, get a job, retire or have a significant event in their lives. Croatia consumes 12 liter per capita in the upper EU countries in terms of alcohol consumption, and the actual consumption of alcoholic beverages is unknown due to a large number of private alcoholic beverage producers. According to the Customs Administration, in 2017 there were 41 650 small producers of strong alcoholic beverages in Croatia reported, and it is estimated that there are significantly more of them in real terms. In both the north and the south of Croatia, almost every house has traditionally produced its own wine for personal use, and today, part of that tradition is preserved, but to a lesser extent[32].

When it comes to attitudes towards alcohol drinking, Croatian society has an ambivalent one. Negative attitudes towards alcohol consumption, especially of young people, are recognized in the legislation and the ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages under the age of 18 and in a public place, in the views of professionals in the health and education system, but on the other hand, it is allowed to advertise alcoholic beverages in the media. Many celebrities from public life participate in those advertisements. The main objective of the research conducted in 2015 as part of the Joint Action to reduce alcohol-related harm (JA RARHA) was funded by the European Union Health Program sponsored by the Croatian Institute of Public Health in the Republic of Croatia to benchmark and monitor the epidemiology of alcohol, including the amount of alcohol consumed, and drinking patterns and alcohol-related harm in the EU[33]. Croatia was one of the 19 EU countries included in the survey, with a sample of 1500 respondents, of whom 49,9 % were male and 50,1 % were female respondents aged 18-64. According to the results of that survey, 78,1 % of all of the respondents drank alcohol in the last 12 months, men 85,3 % and women 71,0 %, and this difference was statistically significant[33].

The results also indicate a tendency to reduce alcohol consumption as a function of age. The majority of alcoholic beverages were drunk by the population between the ages of 18 and 34, 85,0 %, followed by alcohol consumption by 76,7 % between the ages of 35 and 49, and more than 72 % of the population by the age of 50. Among men, 8 % were absolute abstainers, and 19,8 % of women had never drunk alcohol in their lives.

Young men are more prone to drinking than girls in all age groups and 40 % of young men by the age of 15 are more prone to drinking compared to 24 % of girls. The Standardized European Alcohol Survey (RARHA-SEAS) found that in Croatia, the incidence of excessive episodic drinking at least once a month in the last 12 months is 11 %, and is highest in the 18-34 age group and is 17 %. Most people drank (once a week and more often) in their own homes (30 %) and with friends, colleagues, and acquaintances (30 %)[33].

In the last 12 months, 66,2 % of all respondents have drunk beer, 58,2 % drank wine and 45,4 % drank spirits. In the total volume of pure alcohol in the Republic of Croatia in the last 12 months to which the research referred, beer ranked at 56,0 %. %, wine 34,0 %, and spirits 10,0-11,1 % of all respondents drank excessively, i.e. at least once a month, including 16,7 % of male and 5,5 % of female respondents. 16,8 % of them, again, belong in the age group from 18 to 34 years old. Ultimately, the study concluded that Croatia is among the countries (along with Portugal and Romania) with the largest significant gender difference: Croatian males are 5 times more likely to have alcohol problems than Croatian women[33].

DIFFERENCES IN DRINKING CULTURE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CROATIA

Croatia is a very traditional wine-growing country. Wine and the production of wine and other alcoholic beverages have a prominent place in various folk customs and are associated with wine and alcohol with a whole set of customs and beliefs. In some areas, this connection is more pronounced, depending on the middle ground, the rootedness of tradition, and the customs that accompany and emphasize that tradition. Croatian viticulture is an integral part of every farm. But there are differences between north and south in the sale of wine and its role in the community. The importance of viticulture in the north was more strongly related to its integration into the culture, customs and mentality of the population while in the south, existential dependence was more pronounced[34].

In its continental part, Croatia belongs to the pattern of drinking of Eastern and Central European peoples by drinking spirits while in the coastal and coastal areas, it belongs to the Mediterranean pattern of wine-dominated drinking. Croatia has for centuries developed a positive attitude towards alcoholic beverages and drinking alcoholic beverages, and a tolerant attitude towards excessive drinking. In the north, the host, the boss, the head of the house in the family, during various social events and occasions, friendly gatherings and parties, shows his power, hospitality, generosity by constantly pouring “cups” (glasses). Wine is a sign of abundance, friendship and welcome[35].

In this part of the article we will describe the phenomenology and customs related to wine drinking in the north and south of Croatia, from personal and professional experience. As we have already said, the tradition of drinking wine in our region goes back to the past. The phenomenology of wine drinking in the North and the South differs in certain details and reflects the character of the North – the “Northern” way of drinking and the character of the South – the Southern (Mediterranean) way of drinking, its relation to wine and the meaning attached to it. In the north, the host, the boss, the head of the house in the family, during various social events and occasions, friendly gatherings and parties, shows his power, hospitality, generosity by constantly pouring “cups” (glasses). Wine is a sign of abundance, friendship and welcome. Constant pouring, drinking a “cup” bottoms up is a sign of accepting the welcome and respect of the host, as well as expressing the power and health of both the boss, the head of the house and the drinker – a common belief that a strong and powerful, healthy person can drink a lot. The aforementioned paradigm is also seen on daily occasions as calling (paying) a “round” for the friends in the circle, in which the ordering person plays the role of the boss who demonstrates his power. After the first round, it is customary for every member of the circle to call for at least one more round. Workers in Austria and Germany have brought to the northern parts of Croatia the custom of calling the “round” (a drink for everyone in the inn) by ringing the bell (usually at the bar), which is accepted in many hospitality facilities. Each encounter begins with a welcome drink, and ends with a so called ‘one for the road’ drink, which usually does not end with one last, complimentary drink, but multiple. In situations where one hesitates when drinking, they are urged to hurry and drink the already poured alcohol, so that they can pour new ones, to toast and “clink glasses” and to drink bottoms up. If he refuses, his masculinity is called out, and he is encouraged to drink and warned that “only a woman (the weaker sex) can be topped up” (literally and figuratively), but “real men” cannot. In this way, members of society, men, are encouraged to drink bottoms up so that “fresh wine” can be poured. This is how the model of wine drinking develops – to the point of intoxication – excessive drinking without real need and pleasure. Wine is being glorified, quantity and quality go without saying. In this way, the power of both the one who pours (not sparing) and the one who drinks is glorified, because well, he can drink a lot (a symbol of male strength and health). He acts as though he enjoys it, and, in turn, the one who drinks or toasts, is graced by the acceptance from his drinking friends through being loud and gesturing accentuated by such behaviour – constant toasting, lifting and clinking of glasses.

In the south, in Dalmatia, drinking bevanda is traditionally nurtured. One reason is the awareness that wine is “strong” for quenching thirst, and the other reason is “sparing” (“frugality”) as a rational approach in a situation of poverty. Old customs in the south say that only the host can drink “as much as he wants,” and the rule for others is that they can only ‘wet the palate’ with wine and praise the aroma and taste of the host’s wine. The emphasis is on the pleasure; quality over quantity. The host can drink as much as he wants because he is experienced, smart, wise and also aware that the year is long, so he will drink a little too, because tomorrow is another day. There is little wine in the glass, but the quality of it is boasted even when there is nothing to boast. This is probably due to the lack of large quantities of wine and the negative effect on human behaviour correlated with the amount of wine drunk, which is not being approved in the south of Croatia.

In addition to wine, the grape brandy (from grains, residues) is baked in the south, which contains fragrant herbs and mostly medicinal herbs and green nuts (walnut brandy). The brandy is not drunk bottoms up, it is drunk only slightly, in a shotglass called “Bićerin” (a glass less than 0,5 ml), and often it is poured into the Bićerin for stimulation (morning, before meals) or in the evening for “fatigue relief”. Especially strong brandies (spirits, first fruits) are used for external use. Because of the very high concentration of alcohol, there is no pleasure of drinking and it is harmful, so the first fruits are not drunk. The first fruit (the name itself tells them that it is the first brandy that comes out during distillation), come in very small quantities and they are used for massages sick people and disinfection. Cherry brandies are also very famous, which are made by fermenting cherries in jars with added sugar (in the villages there are frequent scenes of cherry jars on windows facing the sun - south). This is generally done by women and it is often women who drink it as liquor in very small quantities in order to enjoy the aroma and taste of this drink. In the north, brandy is baked from various fruits and produced in large quantities (plum, apricot, pear, apple, cherry). Men take care of orchards and vineyards, but men, in general, do not eat the fruit but bake brandy from it.

When we talk today about the St. Martin’s Feast, we regularly think of celebration, wine, booze and fun. Ever since and to what extent is wine connected with St. Martin in the northwestern Croatian territories, and whether people have always looked forward to Martin’s Day, are questions that are almost impossible to answer. The Croatian northwest includes Zagorje and Međimurje geographically, traditionally wine-growing regions whose main and most attractive annual feast from ancient times to the present day has remained dedicated to St. Martin[36], Figure 1.

Wine in the south is given the significance of a hedonistic remedy (the pre-Christian culture of celebrating the Roman god of wine Bacchus, the Greek god of wine Dionysus) to the Christian culture of moderation summarized in the slogan – “drink a little, drink well.” Only

on Good Friday is wine given a religious meaning – it is believed that red wine that is drunk during Good Friday is directly converted to blood, Figure 2.

The aforementioned phenomenology and customs related to drinking vary from place to place, from village to city, and lately there has been a noticeable change in the drinking paradigm in both the north and the south – the advancement of viticulture, competition in the quality and knowledge of varieties, flavours and aromas, especially in elitist circles of society, which tends to change the paradigm of traditional customs described. It should also be emphasized that statistic have confirmed an increasing number of beer drinking in the male population in the wine-growing regions of the north and south of Croatia.

The customs described are mostly related to men. The roles of women – mothers in the family and attitudes towards women in the north and south also differ, and these differences need to be taken into account in clinical work and in the therapeutic approach. The family approach to alcoholism treatment was introduced by Hudolin long ago, and he based his method of treating alcoholism (today’s Zagreb School) on family therapy through the Clubs of Alcoholics in Treatment.

Our clinical practice shows us the differences in the traditional role of women in the north and south of Croatia, which are reflected in the dynamics of the partner relationship, the occurrence and maintenance of alcoholism of men (partners) and its treatment. Leinert Novosel’s research shows that in Croatian society, women continue to retain the traditional role of caring for children and families. In our experience of working with families of alcoholics, we notice a difference in the role of women in the north and south of Croatia, which will be discussed further in the text.

DIFFERENCES IN THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN FAMILIES IN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CROATIA

As stated earlier, in the northern parts of Europe, where gender equality is higher, the gap between the incidence of drinking alcohol between men and women is decreasing. On the other hand in longitudinal research Leinert Novosel showed a high degree of egalitarism in the Croatian public sphere, controlled by different kinds of profession and role characteristics but in the private sphere, it was shown that women today have even more difficult role in the family than before – women again play their traditional roles, such as taking care of children[37].

In the north, the mother is powerful, firm and determined, often performing “men’s jobs” (working in the field, caring for livestock, etc.), setting boundaries in the family and emphasizing a rational approach. It is often dominant in the private as well as in the public sphere. The woman often assumes responsibility for the family, provides material resources for her survival, takes care of the upbringing and health of children and the husband, most often neglecting her own health and neglecting her own satisfaction in the partnership and family. Due to the stated role of women in families in the north, families in which the father is an alcoholic do not perish (materially, economically). Family failure is more likely if the mother/wife becomes an alcoholic.

This is stated in the well-known poem from Međimurje county “Children, My Children”, by Elizabeta Toplek, which states: “My children, my children, you shall never have anything, your mother is to blame, she drank it all”! And many studies show that parental alcohol abuse, especially maternal alcohol abuse, has extremely damaging psychological and social consequences for children who themselves are at risk of developing addiction[29]. There are probably many factors that have contributed to women’s dominance and family structure in northern Croatia. Poverty of the predominantly rural population of Međimurje and close proximity to the border, transport and historical connection with the countries of Central Europe caused the emigration of the population, mostly of men in earlier periods, and the expansion of emigration and chain migration was recorded in the 1960s when about 10 % of the total population of Međimurje emigrated[36]. Absence of husband/father (fieldwork, working abroad, alcoholism) is certainly an important factor that has determined the dominant role of women in the family. Also, in the not-too-distant past, it was common in the northern parts of Croatia and Slavonia to marry (arranged or “for love”) at an earlier age, so newlyweds were often 16/17 years old. Brides, girls, have been more mature and thus often assumed a more dominant role in the partnership that took place during marriage, and by transgenerational transmission this way of domination of the woman and her role in the family was passed on to and to younger generations, and partly preserved to this day.

According to our observation, the role of the mother in the southern parts of Croatia, the mother has a paradigmatic Marian role: she is the one who supports the patriarchal family structure. The emphasis is on the principle of sensitivity and unconditional love. According to the children, the mother is “weak”, indulgent, difficult to establish discipline and boundaries, and in the absence of her father (e.g. work abroad) has problems due to a withdrawal of authority and setting the boundaries. In the southern regions, because of that, the child is presented with a father figure in the form of threats, of course, in situations of “female” powerlessness: “you will see when He (your father) gets you!” It should be noted that these patterns of mother’s role in the family vary from family to family, from woman to woman, and that generalizations are not possible, but should be taken into account when reflecting family dynamics and the impact on family relationships, and the possible role in the genesis of alcoholism in family members.

Because culture is a social product that is created, transmitted, and sustained through communication and learning, so are the social narratives and behavioural styles associated with drinking wine and alcoholic beverages generally important for the genesis of alcoholism. Although it is necessary to take into account the influence of biological, psychological and social factors contributing to the onset of alcoholism and the outcome of therapy, as well as the success of changes in the whole family system, we wanted to emphasize in this article the need for a therapeutic approach in the treatment of alcoholism that will take into account the differences in the drinking culture and the role of women in families in the north and south of Croatia. The differences observed in clinical work, as well as the results of other authors’ research, indicate the importance and need to investigate addiction through a gender-responsive approach, and the need to take into account the specificities arising from these differences when planning addiction prevention programs and treatment programs (Wetheerington, 2007.)[29].

The relevance of alcoholism as a medical and social problem will also be demonstrated through the prism of the number of suicides committed and the number of hospitalized persons from post-traumatic stress disorder, who are ethiopathogenically likely to be interconnected and often intertwined with alcoholism. This is important because of its impact on the therapeutic guidelines and the outcomes of the treatment itself[18, 19].

SOME STATISTICAL INDICATORS OF ALCOHOLISM AND MENTAL DISORDERS IN CROATIA

Hudolin et al also noted that at least 20-30 % of psychiatric diagnoses were caused by alcohol, but few were verified to be a result of alcoholism. In a study conducted in 2014 by M. Rapić and M. Vrcić-Keglević, the results of the study indicated that, in parallel with the increase in the total morbidity registered in family medicine from 1995 to 2012, the incidence of mental illness also increased. Mental illnesses accounted for 4,2 % in 1999, and 5,8 % in 2012 for total morbidity. An increase was observed in all mental illness groups, except for conditions related to alcoholism. In 1998, alcoholism accounted for 9 % of the total mental illness, and in 2012, only 3,2 %, with a decrease in all age groups. Looking at the absolute numbers, only 21 077 patients with alcoholism were registered in general practice in 2012, i.e. 0,6 % of the adult population. The authors rightly conclude that the number of registered alcohol-related diagnoses, especially their steady decline, is unlikely to be true[38]. The 2003 studies by Benčević-Streihl et all. on alcohol consumption in Croatia indicate that excessive drinking is present at 12,3 % of men and 0,7 % of women surveyed[30].

According to the Croatia Institute of Public Health (CIPH) data, alcoholism is number one reason for morbidity of hospitalized patients due to mental disorders in northern parts of Croatia and schizophrenia is the number one reason for morbidity of hospitalized mental disorders in southern parts of Croatia[39].

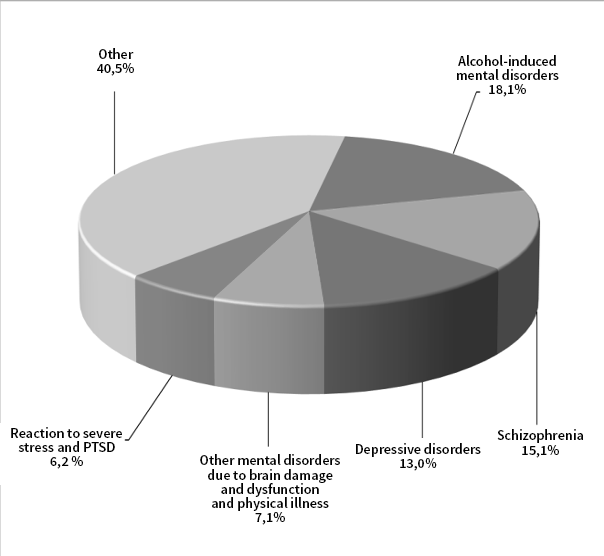

According to the CIPH data in the publication “Mental disorders in the Republic of Croatia” from 2018, it is clear that mental disorders caused by alcohol, schizophrenia, depressive disorders, mental disorders due to brain damage and dysfunction and physical illness and reactions severe stress and adjustment disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as separate diagnostic categories, account for almost two-thirds of the causes of hospitalizations for mental disorders[29], Figure 3.

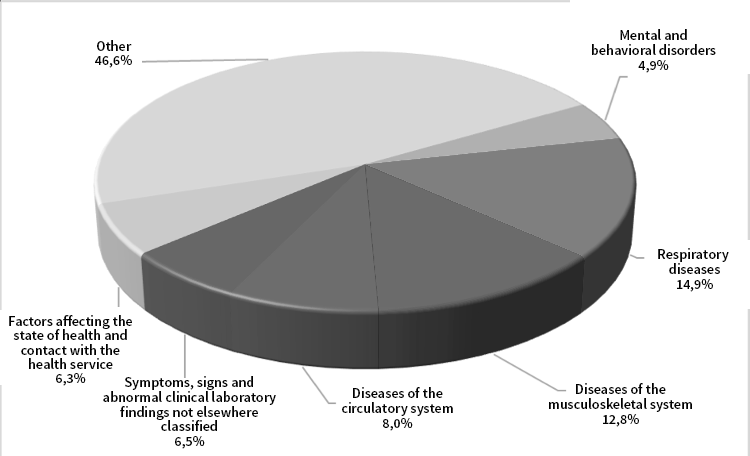

According to the CIPH, of all the diagnostic categories of mental disorders, mental disorders caused by alcohol are the most common cause of hospitalizations at a rate of 18,1 %. Compared to hospitalization data in general practice, mental disorders are markedly neglected. According to the CIPH data for 2017, the prevalence of mental disorders and behavioural disorders in primary health care is significantly lower, amounting to only 4,9 % of all[39], Figure 4.

Rapić and Vrcić-Keglević in their work Alcoholism – Forgotten Diagnosis in Family Practice analyse mental illness (category “F”, ICD-10) in family medicine with special reference to alcoholism (F10.2) from 1995 to 2012, and note that in 1998 alcoholism has contributed 9 % to mental illness in family medicine, and in 2012 only 3,2 %. The authors wonder whether the phenomenon of stigmatization of alcoholism is still present, not only among patients and their families, but also among doctors, whether these are difficulties and uncertain outcomes of treatment, or whether other, more modern, diseases have suppressed this disease in the subconscious of doctors[38]. Other issues could be added to these issues, such as those related to the content and scope of undergraduate medical students and subsequent specializations in general medicine in the field of psychiatry and mental health care, such as the lack of primary care psychologists, the less frequent conduct of systemic exams and changes in the labor market.

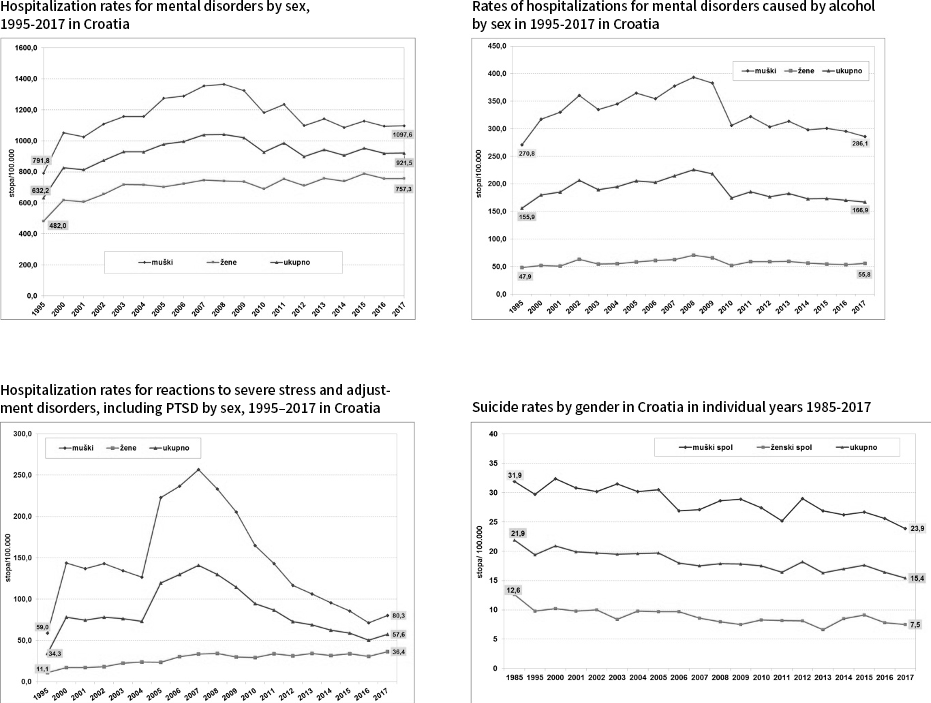

There is also a marked coincidence of suicide rates with the prevalence of alcoholism and the rate of mental disorders caused by stress. In almost the same observation period (1995 to 2017), according to CES data, it is noticeable that women are significantly more hospitalized for depression (F32-F33) and men for PTSD (F43.1), which is understandable for the participation of men in the Homeland War, Figure 5. A disease specific to the veteran population is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). According to data during 2016, 31 337 Croatian veterans used health care for this disorder. The largest number of such veterans is 5 397, from Split-Dalmatia County, followed by 4 510 veterans from Osijek-Baranja County, 2 993 from Vukovar Srijem County and 2 615 from City of Zagreb[25]. According to the CIPH data (2017), 21 236 veterans were registered in the Republic of Croatia in 2016 who, because of their depressive disorders, used health care[25]. Veterans are particularly vulnerable to the suicides of their fellow soldiers. Between 1991 and 2015, 2 734 veterans committed suicides in the Republic of Croatia. In the last three years (2013-2015), the veteran population has committed twice as many suicides as other civilians, making it the most vulnerable social group. About 150 veterans’ suicides occur annually and this number is on the rise, and according to media reports in September 2019, 3 246 veterans have committed suicide since 1991[40].

Comparing the rate of hospitalizations for mental disorders in the Republic of Croatia, the rate of hospitalizations for mental disorders caused by alcohol, the rate of hospitalizations for severe stress reactions and adjustment disorders including PTSD and the rate of suicide by sex in the Republic of Croatia from 1995 to 2017, according to the data from CIPH[39], which is significantly dominated by men, there is no doubt that mental disorders caused by alcohol are probably factor in making this difference at significantly higher rates in men more than in women, Figure 5.

It is also important to analyse the suicide rate in the Republic of Croatia due to the well-known fact that completed suicides are dominated by men and in women’s attempts, and that up to 80 % of suicides have been committed while intoxicated - three quarters of men and a quarter of women who commit suicide (75,6 % of men according to 25,4 % of women) committed suicide while intoxicated.[40] Generally speaking, psychiatric disorders are the most common causes of suicide, in almost 90 % of cases. Of these, depressive disorder is the cause of suicide in 60 % to 80 % of cases. Abuse of psychoactive substances and alcohol, especially in young people, is the second most frequent cause of suicide, from 5 % to 15 %, while psychotic disorders are the third cause of suicide in about 10 % of cases, followed by dementia and delirium. Mourning and prolonged social difficulties (e.g. unemployment) are the causes of suicidal behaviour. Social isolation – Single life, lack of confidence and warmth can also be a causal factor for suicidal behaviour[42].

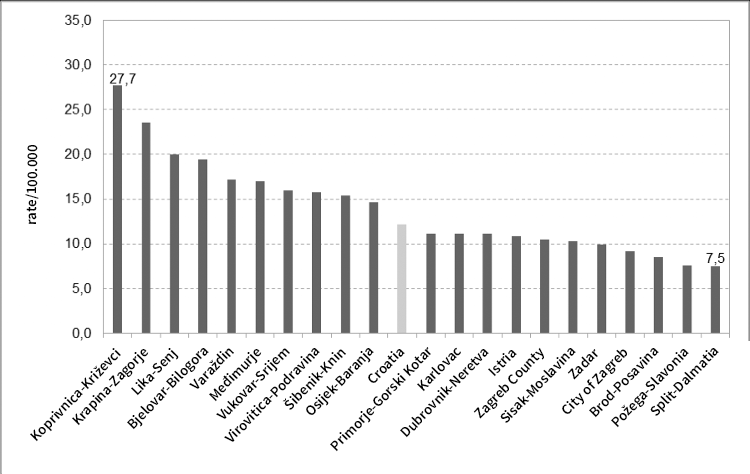

It is also important to compare suicide rates by county, which could be put in the context of drinking culture, the incidence of alcoholism and the impact on suicide rates in the population, Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows that the suicide rate is higher in the northern counties and is above the Croatian average, while the suicide rate in Split-Dalmatia county is the lowest (7,5). The fact is that the suicide rate in the northern counties of Croatia is higher than in the southern counties, and alcoholism is known to be a risk factor for suicidal behaviour. Brečić states that 20-50 % of suicide perpetrators are alcohol addicts, i.e., 30-80 % of suicide victims were intoxicated at the time of suicide[25].

According to the data provided by the Croatian Institute of Public Health, age-standardized rates of suicide deaths in Croatia for all ages and ages up to 64 show fluctuations until 1997, and since 1998 there has been a fall in rates (in 2016, the rate of 1,2/100 000 for all ages and 10,9/100 000 for ages 64 and up). For ages 65 and older, the rate, with more pronounced oscillations, has also declined significantly since 1998 (in 2016, the rate is 31,3/100 000). There are differences in age-standardized rates among Croatian counties. Counties in the coastal part of Croatia have lower rates of suicides than some continental counties[26].

What many experts agree on, as indicated by the results of numerous studies, is the need to take into account the sociocultural influences and specificities of a particular country when designing prevention and promotion programs as a precondition for their success, and that there should always be sensitivity to cultural differences when planning interventions and therapeutic procedures in the treatment of alcoholics.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have described the customs and culture of drinking wine and alcoholic beverages in the north and south of the Republic of Croatia, and the impact of culture on the incidence of alcoholism and problems related to excessive drinking.

The increased incidence of alcoholism in the north compared to the south of Croatia and the increased prevalence of alcoholism in men are related to the culture and tradition associated with drinking alcoholic beverages. The incidence of alcoholism is influenced by many factors, ranging from the biological and psychological characteristics of individuals and their families, as well as social attitudes related to drinking and excessive drinking. The social acceptability of excessive drinking is particularly emphasized in the northern parts of Croatia, and the influence of drinking culture on behaviour, especially of men, is undoubtedly important, which affects the choice of therapeutic techniques and therapy goals, as well as the treatment outcomes and the occurrence of recidivism. Data from clinical practice and numerous studies support the reduction of differences in alcohol drinking between men and women as a negative consequence of gender equality by adopting the same patterns of alcohol-related behaviour and the early entry of young people into the world of alcohol consumption. Because of the above, interventions in terms of changing the social narrative related to drinking alcohol and respecting the cultural and historical legacy of alcohol consumption in the north and south of Croatia in treatment could have a beneficial effect on reducing the incidence of alcoholism, suicide, and recidivism.

Involving the family in the treatment of addiction is of great importance (the role of Clubs of Alcoholics in Treatment – CAT), as well as the involvement of the entire work and social environment in reducing the harmful effects of alcoholism on the individual, family and the wider community. Although it is necessary to take into account the influence of biological, psychological and social factors that contribute to the onset of alcoholism and the outcome of therapy, as well as the success of changes in the whole family system, in this article on alcoholics, we wanted to emphasize the need for a therapeutic approach in the treatment of alcoholism that will take into account the differences in the drinking culture and the role of women in families in the north and south of Croatia.

Social change in the drinking culture requires broader social engagement and public health policies that promote non-drinking, which in the long run will change attitudes, values, and behaviours related to alcohol drinking and the emergence of alcoholism, which is still a major public health problem without adequate prevention and with an underdeveloped rehabilitation. The article emphasizes the need to take into account the sociocultural influences and specificities of a particular region when designing prevention and promotion programs as a precondition for their success and the need to always have a sensitivity to cultural differences when planning interventions and therapeutic procedures in the treatment of alcohol addicts.