Introduction

Ever since it appeared in scientific and professional circles, the concept of legal culture has been an enigma for those interested in the topic. The challenges have stemmed from difficulties in defining the meaning and scope of legal culture and determining its measurable components.

The creator of the concept, Lawrence Friedman, in an article “Legal Culture and Social Development” published in1969, identified legal culture as a critical link between law and society. In The Legal System: A Social Science Perspective (1975), a monograph representing the backbone of legal culture, Friedman further elaborated the concept as the third component of the legal system that gives life to the static legal structure and substance. He defined legal culture as a part of general culture consisting of attitudes and values about and towards law, which affects the constitution of relation with the law and consequently influences the position of the legal system in society (Friedman, 1975). On those grounds, many discussions, analyses, and critiques have been initiated and published over the years in edited volumes and monographs concerning the issue of legal culture.1 Hence, Friedman’s broad understanding influenced the overall application of the concept. Besides law and sociology, and especially the sociology of law, in which legal culture is marked as an essential component of analysis (Friedman, 1990, inCotterrell, 2006), anthropology, political science, economics, and other social sciences also show interest in the concept.

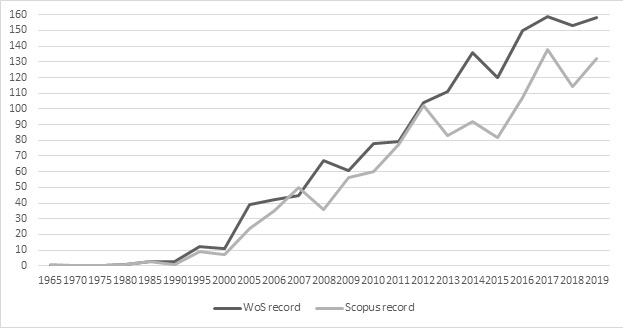

Except in contributed volumes, this growing interest and application of the term may best be recognised in the number of articles dealing with legal culture recorded in two major, world-leading multidisciplinary index and citation databases – Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus (Figure 1). According to Web of Science result analysis, 1301 documents (847 articles, 34 reviews, 60 book chapters, nine books)2 were published from 1955 up to 2019 concerning legal culture as a topic (“legal culture” as a phrase in the title, abstract, keywords). I encountered almost the same situation with publications addressing legal culture published in the period 1960–2019 and indexed in Scopus – 1349 document types containing “legal culture” in the article’s title, abstract, or keywords (739 articles, 194 reviews, 249 book chapters, 108 books).3

Although more than 20 years have passed since the early critical review papers, in that exact period, asFigure 1 shows, a major scientific boom of "legal culture" occurred. New articles, growing in number and versatile application of the term legal culture, have prompted new and still ongoing criticism regarding the meaning and usefulness of the concept. Therefore, the question is whether legal culture has become a clearer and more relevant concept that can provide answers to the increasingly present, intricate relations between society and law. More specifically, have these numerous scholarly papers made the concept of legal culture more comprehensible and coherent?

With the idea of elucidating the state and usage of the term legal culture in science, this article raises the following research questions:

- How do authors define legal culture; how is it conceptualised (composed of which elements/variables) and operationalised (methodology and method)?

- Do authors deal with legal culture theoretically or empirically? Does qualitative or quantitative research on legal culture prevail?

- What are the main topics of articles that use the term legal culture?

- Is there any specific approach to legal culture given the topic of the articles (i.e., the same or similar interpretation, definition of legal culture, same/similar methodological approach)?

- Are certain topics, theoretical and empirical approaches to legal culture related to a particular geographical area?

To answer these questions, I conducted a systematic literature review in which I identified the diversity and variety of meanings and applications of the concept of legal culture in the academic community. In the rest of the paper, I first explain the methodological procedure that guided the systematic literature review and then present the results of the analysis organised in eleven sections that follow inductively defined topics related to legal culture. Finally, in the conclusion, I summarise the analysis findings, evaluate the observed state of the academic approach to the legal culture and propose improvements regarding the comprehensibility and application of the concept.

Method

In this paper, I analysed the content of scholarly papers that dealt with legal culture to investigate approaches, differences, and similarities in understanding, defining, and studying this concept. I analysed the articles available in two world-leading index and citation databases – Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The disadvantage of limiting the analysis to these two databases is that it does not include important volumes focusing on theoretical aspects of legal culture and monographs of extensive legal culture research that had a significant impact in the field. But this pragmatic approach enables a comprehensive and systematic analysis of articles that, due to the accessibility and visibility of WoS and Scopus indexing, shape the field and picture the current state of legal culture in scholarly writings.

The key criterion for selecting the articles for analysis was that the term legal culture was part of the title. Papers had to be scientific, published in peer-reviewed academic journals, and written in English. Given the time criterion, the analysis included articles published from the beginning of indexing in databases (in the case of WoS from 1955 and in Scopus from 1960) until the end of 2019. Along these lines, I retrieved 149 scholarly articles from Scopus and 155 from WoS. Upon merging the articles into a single analytical database, their total number was 239 (65 articles were listed in both databases). After skimming, articles whose full text was not in English (8), book chapters (26), book, conference, and teaching material reviews (4), and articles unavailable online (2) were excluded from the analysis. Thus, the final database of scholarly articles with the term “legal culture” in the title, written in English, and published in academic journals from 1955 to 2019, contained 199 items.

After selection, I analysed the articles concerning the main topics to which legal culture relates, interpretation and conceptualisation of legal culture, applied methodological approaches in the study of legal culture, and geographical area of conducted research on legal culture.

For the results to be presented systematically, I summarised the articles under inductively defined topics. Thus, scholarly articles are gathered in eleven sections: theoretical and empirical papers on legal culture, popular legal culture, legal education, internal legal culture, local and international legal culture, politics and law, laws and legal aspects, national legal culture, and legal history.

Before presenting the results of this qualitative analysis, it is necessary to point out the limitations of the conducted systematic literature review according to the indicated criteria. The main limitation of the research is that it includes only those articles addressing the term legal culture in their titles. I based this criterion on the notion that the titles of scholarly articles accurately and informatively reflect the paper’s content. However, it is clear that articles of a different title also address legal culture, as shown by the data presented in the introduction. The same can be said for the limitation regarding the language. The analysis includes only articles in English, although it is clear that this is a globally important and scientifically recognised research field with a significant number of articles on legal culture written in other languages, as indicated in Scopus and WoS. The inductively produced thematic classification of papers also has its drawbacks, primarily related to potential topic overlap. Besides, this analysis does not include articles dealing with the subject of legal culture under some other name, respectively papers with different terminology, and “synonyms” such as legal consciousness or awareness, addressing potentially the same or a similar phenomenon. Still, despite the limitations, the research approach used in this review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of scientific analysis of legal culture, its scope and constraints.

Legal culture in theory

The starting point for presenting the results of this systematic analysis of articles covering legal culture, or which at least mention this concept in their title, is a review of theoretical articles discussing the concept itself. These articles define the legal culture, discuss the importance of the concept and its functions, overview the use of the term, or suggest methodological approaches to legal culture. Although the articles are strictly theoretical and not linked to any specific location, the analysis showed a noticeable and significant interest in legal culture by authors from Eastern Europe and Asia.

Among the theoretical papers is Friedman’s well–known, founding article for the field of legal culture published in 1969. According to Friedman (1969), a legal system consists of three components - structure, substance, and legal culture. The structure unites legal institutions, their organisation, and action, while the substantive component embodies legal content – laws, legal procedures. Finally, the cultural component represents values and attitudes that connect the legal system and determine its position in society. Thus, research of legal culture should identify the reasons and conditions within which there are changes in the legal system and those that make the legal system stable and efficient. “It is the legal culture, that is, the network of values and attitudes relating to law, which determines when and why and where people turn to law or government, or turn away” (Friedman, 1969: 34). Almost 50 years later, Friedman (2014) determines commitment to the rule of law as one of the traits of modern legal culture.

Besides Friedman, other authors offered their views and definitions of legal culture. For instance, legal culture represents a “sense of justice and the level of law-enforcement activity in the interest of securing and strengthening the rule of law and legality” (Akhmetov, Zhamuldinov and Komarov, 2018: 2219), or a transition from a static view of legal dogma to legal dynamic (Andreeva et al., 2019). Besides, legal culture is a type of general culture and part of social life that ensures social solidarity and is recognisable in economic conditions, showing a level of effectiveness of the state’s legal system (Kulzhanova and Kulzhanova, 2016).

But even more than focusing on new definitions of the concept, the theoretical articles were centred on explaining the problematic nature of legal culture, questioning the purposefulness and usability of such an intricate concept. The initial issue is terminology, i.e., the use of "culture" and "legal", which are in themselves complex concepts and largely depend on the discipline from which one starts (Nelken, 2014). In addition, theoretical difficulties emerge in determining the subject of study, such as defining the area (locality) – global, national, judicial, individual legal culture; defining indicators, objects of legal culture – legal system, institutions, alternative forms of dispute resolution, behaviour; or defining legal culture through the gap between law in books – instrumental conceptions of the role of law, and law in action – actual application of law and law enforcement (Nelken, 2014). Critique recognises the difference between “those (often positivist) scholars who look for 'indicators' of legal culture in the activity of courts and other legal institutions and those who insist instead on the need to interpret cultural meaning” (Nelken, 1995: 441). Besides, researchers have different approaches in treating legal culture as a variable in explaining social behaviour or as a separate research phenomenon in which a number of elements are linked (Nelken, 1995). Likewise, a distinction is identified between the use of legal culture as a background to law, as an interaction around the law, and as a sum of attitudes towards the law (Fekete, 2018) and in the use of legal culture as a fact, as an approach, and as a value (Nelken, 2014).

These diverse approaches and problems of legal culture are explained mainly by the scientific field. For example, comparative law uses legal culture to reveal differences in legal systems. In contrast, there is a descriptive purpose in legal history "to identify a specific segment of legal experience from earlier periods, whose characteristics it reconstructs by referring to archival materials" (Salter, 1995: 454). On the other hand, the sociology of law employs the concept as shared legal experiences of lawyers and laypeople (Salter, 1995).

Besides definitions and critiques, the theoretical articles also advocate a specific approach to the legal culture that should disentangle the concept. Thus, macro-sociological, positivist studies of collective dimensions of legal actions are challenged by micro-sociological approaches focused on subjective interpretations of legal facts (Salter, 1995). Within the latter approach, some authors advocate an anthropological analysis of legal texts (e.g., court records of a particular case) (Engel and Yngvesson, 1984), while others are more inclined to the phenomenological approach focused on individual awareness and understanding of the law and legal culture (Salter, 1995).

Empirical research of legal culture

Although legal culture has proven to be a fruitful scientific field, given the significant number of articles, it does not abound in empirical research. This section brings together articles unique for addressing legal culture as a dependent variable and presenting the characteristics of the legal culture of European and Asian countries or their specific population groups based on conducted empirical research.

In the conceptualisation and operationalisation of research, the authors start from different theoretical frameworks. Some definitions are quite extensive, in which legal culture “entails patterns of social thought and behaviour concerning law” (Potter, 1994: 44) or represents “the individual’s total body of knowledge, values, and attitudes in regard to his rights and the opportunities to exercise them in practice. Legal culture represents a comprehensive complex of phenomena of civic life, one that includes legal norms, principles, awareness of the law, legal relations, and legal behavior in the process of realizing the goals of life” (Zubok and Chuprov, 2007: 73-74). Others, on the contrary, focus more on perceptions and attitudes towards law and law enforcement (Miller, 2012), or even more concretely, on appropriate ways of resolving disagreements and process disputes (Bierbrauer, 1994).

Differences in definitions are manifested and even more visible in conceptual and methodological approaches to legal culture research. In a study on the legal culture of adolescents in Russia and Belarus (Zubok and Chuprov, 2007), or of primary school students (Zemlyachenko, 2014), the authors explore the concept through cognitive (knowledge of the rights, freedoms, civic, ethical, and legal values), emotional and evaluative (respect for rights and freedoms according to legal and moral norms, dignity of other people, nations and negative evaluation of violations of laws and social norms), and behavioural components (skills of acting in accordance with the law, resolving and preventing conflicts, acting by obligations, guided by personal qualities of decency, tolerance, discipline, respect for rights and freedoms of other citizens). On the other hand, in the research on Chinese business operators’ legal culture, Potter (1994) puts focus on the attitudes on equality, justice, and private law relations, while Bierbrauer’s (1994: 248) study on German, Kurdish and Lebanese legal culture measured five attitudinal components: general legitimacy and acceptance of authority, legitimacy of norms for dispute resolution, procedural preferences, goals of dispute resolution, and discretion and particularism in legal decisions. Gibson and Caldeira (1996) conceptualise legal culture through the valuation people attach to individual liberty, their support for the rule of law, and their perceptions of neutrality in law. A completely different approach to legal culture research highlights the difference between the living law and law in books, and analyses institutional accessibility to law, the number of legal professionals and their training, the number and organisation of courts, the number of civil litigation and criminal proceedings (Blankenburg, 1998). In methodological terms, this group of articles predominantly derives results from survey questionnaires conducted on non-random samples of children of different ages (Zubok and Chuprov, 2007;Zemlyachenko, 2014), specific social groups (Bierbrauer, 1994;Potter, 1994), or a representative sample of the general population (Gibson and Caldeira, 1996;Bierbrauer, 1994;Miller, 2012). In addition to the quantitative approach, legal culture was explored using qualitative methods – interviews (Kurkchiyan, 2009;Miller, 2012) and focus groups with citizens and minority groups (Miller, 2012). Besides, the secondary analysis of the data on legal systems used by Blankenburg (1998) is significant.

Professionals’ legal culture

This topic brings together articles on the particularities of legal professionals’ work, peculiarities, and challenges in legal practice, e.g., ways legal professionals adapt to changes in legislation, comply with a certain law, commit to legal tradition, or even how they handle stress in the legal profession. In this approach, the bearer of legal culture is a specific group of people – experts in law such as prosecutors, judges, and lawyers, but the importance of legal culture in practice is recognised in the public servants’ work as well. Because of that, legal culture is associated with professionalism in performing tasks related to law and the legal system. There is even an idea of conceptualising legal culture as an organisational culture based on Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Chan, 2014). However, most articles found their theoretical background in Friedman's, Nelken's, and Klare's understanding of legal culture. Thus, legal culture represents attitudes and values of legal practitioners with a reference to Friedman’s notion of internal legal culture (Montana, 2012;Chan, 2014;Zimmermann, 2016). For instance, Hunt (1999: 87) defines legal culture as “professional sensibility, habits of mind, and intellectual reflexes”.

In all articles, (internal) legal culture is considered a critical intervening variable that impacts legal practice and a differentiating factor that affects the relation between the law in books and the law in practice. Considering the regions the authors represent, it affects legal professionals worldwide, from Italy to the UK, Kazakhstan, and Latin America. But even in this case, there are relatively few empirical papers that truly investigate this impact of legal culture. In this sense, Montana's (2012) paper based on qualitative research, i.e., semi-structured interviews with legal professionals, stands out.

Local legal culture

The articles on local legal culture address the work of legal professionals, emphasising the specifics of the functioning of a group of lawyers or court members in specific issues or typical cases. Church (1985: 451), as the first author employing the term local legal culture, used it to refer “to practitioner norms governing case handling and participant behaviour in a criminal court”, i.e., “to the norms and attitudes concerning case disposition and participant behaviour commonly held by practitioners in local trial courts” (Church, 1985: 450). After testing preferred forms of resolving criminal cases among prosecutors, lawyers, and judges, Church concluded that local legal culture has a strong influence on uniformity and specific decisions in matters of a procedural nature: the duration of the trial and trial as necessary way of resolving a criminal case. On Church’s foundations, Crank (1986) singles out four variables, indicators of a local legal culture: preferred course and duration of litigation, preferred punishment, attitudes about deserved punishment, and interpersonal relationships of legal practitioners. In this way, local legal culture represents a variable affecting caseflow management (Sherwood and Clarke, 1981;Steelman, 1997).

In addition to Church, Sullivan, Warren, and Westbrook’s (1994;1997) work on consumer bankruptcy cases was very influential in this area. They recognised local legal culture as a crucial factor interfering with the implementation of formal rules. In their view, local legal culture represents “systematic and persistent variations in local legal practices as a consequence of a complex of perceptions and expectations shared by many practitioners and officials in a particular locality, and differing in identifiable ways from the practices, perceptions, and expectations existing in other localities subject to the same or a similar formal legal regime” (Sullivan et al., 1994: 804).Their work motivated further research on Chapter 7 and 13 fillings in a case of personal bankruptcy in the USA. The key conclusion is that there are differences in local legal cultures, i.e., local courts make different decisions in similar cases, which points to significant differences between the law in books – formal law and outcome, and the law in action (LoPucki, 1996).

Authors investigated local legal culture with diverse empirical approaches, such as in-depth interviews with court members (Sullivan et al., 1994,1997;Currul-Dykeman, 2014); attitudinal questionnaire and questionnaire on the appropriate mode of handling trial in hypothetical cases (Sherwood and Clarke, 1981;Church, 1985), secondary data analysis (Crank, 1986;Sullivan et al., 1994,1997). And while methods vary, the geographical field of research is relatively homogeneous – almost all articles under this topic focus on local legal cultures of practitioners and courts in the United States of America, derivatives are within specific regions or city courts.

Legal culture in and for legal education

Articles dealing with legal education focus on the adoption and shaping of legal culture as a key outcome of education, but also of socialization. From that point of view, legal culture can be improved at different stages of life and formal education since it is considered an important component of preschool education, students' vocational education, bachelor and law studies, but also for the general population (Absattarov, 2019;Nabievna and Manafovna, 2019), or even more specific groups, such as transport specialists (Bagreeva, Zemlin and Shamsunov, 2019).

Although the articles differ regarding the definition and agents, they emphasise one component of legal socialization and legal culture – legal knowledge. This unique element distinguishes the notions of legal culture in education from other topics of this analysis. Thus, legal culture is a part of students' cultural identity and consists of legal knowledge and skills (Togaybaeva, 2013). Conceptually, legal culture represents “a combination of legal knowledge, the relation to the law as a value and lawful behavior; as a socio-pedagogical phenomenon – is investigated as a measure and a way of creative self-realisation of a person in legal regulation of his future professional activity” (Sovhira, Bezliudnyi and Pidlisnyi, 2019: 790).

The analysis of the retrieved articles suggests that the issue of legal education and the adoption of legal culture as an important segment of socialization at different stages of life are predominantly interesting to the countries of Eastern Europe and Asia (Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan). However, only a small number of papers measure legal education or legal culture. Those that induce an empirical research approach use questionnaires or experiments as a method (experimental and control groups of students exposed to specific legal contents). The theoretical and descriptive approach is much more frequent, i.e., many more articles point to the importance of legal education, which would lead to the strengthening of the state’s legal system.

Legal culture in art and media

Articles grouped under this topic are concerned with legal culture, its creation, and transmission through media content and art. The majority of the articles do not offer any theoretical background for implementing the term legal culture. At the same time, in discussing the importance of media in communication between law and society, some authors go further into the theoretical approaches of Durkheim and Weber or Holms and Dewey (Silbey, 2004). Those defining legal culture base their theoretical considerations on Friedman’s perspectives (Davinger, 2012;Wolfgram, 2014), but with an additional explanation and a specific name - “’popular culture gets its ideas of law, or at least some of them, from popular legal culture’, but ‘popular legal culture also creates popular culture, in so far as it acts as a medium or channel for transmitting values and attitudes’” (Friedman, 1989 inDavinger, 2012: 154-155).4

The sources of popular legal culture, i.e., law understanding, are films (Davinger, 2012), written media – newspapers and magazines (Haiba and Matar, 2017), and poems (Hasanov, 2017). The Internet (Kovalenko, Kovalenko and Gubareva, 2018) and technology (Silbey, 2004) are essential for today’s legal culture development. Mass media are in charge of and responsible for informing on legal topics, they “spread legal culture” (Haiba and Matar, 2017: 105). They influence the perception of transparency of the decision-making process, critical perspectives on law, and engagement with law, by forecasting Supreme Court decisions (Silbey, 2004) or presenting trials for Nazi crimes in Nuremberg, Frankfurt, Auschwitz, and Majdenka (Wolfgram, 2014). In that way, art and media can affect and improve legal culture, consciousness, or legal awareness, the terms some authors use interchangeably.

The primary empirical approach is the analysis of media content – films, TV shows, newspaper articles, poems, although only a few authors explicitly indicate the method used. Geographically, legal culture in art and media is recognised in articles dealing with the USA, Germany, Arab countries, and Russian Federation or aiming at a general understanding of the impact of art and media on legal cultures.

National legal cultures

Although many of the analysed articles could be subsumed under the section on national legal cultures, this group consists only of those that, at a general level, try to explain the characteristics of a specific legal system (or legal culture). The main themes of the articles are national legal systems and cultures of, for instance, France, the United States, Kazakhstan, China, Brazil, Mexico, and Spain, which makes this group of articles geographically diverse and heterogeneous.

Prevailing theoretical starting points for these articles are Friedman’s and Cotterrell’s understanding of legal culture as attitudes, beliefs, values, and patterns of behaviour towards the legal system (Garapon, 1995;López-Ayllón, 1995;Bu, 2015). What is also used is Bell’s somewhat different interpretation of legal culture as “a specific way in which values, practices, and concepts are integrated into the operation of legal institutions and the interpretation of legal texts” (Bu, 2015: 104). Legal culture is also understood quite broadly as a “set of shared understandings” (Garapon, 1995: 494) or narrower – as legal practice and choices made by legal professionals (Atias and Levasseur, 1986;Heifetz, 1999: 695).

What is specific about this group of articles is that the traits offered in explaining national legal cultures (systems) are not precisely comparable between nations. Some point to legal professionals or what Friedman would call internal legal culture, while others put focus on the prevailing social perspectives or cover the procedural and organisational features of the legal system. For instance, the main features of the Brazilian legal culture are “persistent denial of any general or abstract regulatory standards, the uncritical introduction of foreign doctrines and legal patterns, the maintenance of aristocratic traditions in social life and the historical disregard of the Brazilian people as political subject” (Matos and Ramos, 2016: 753). On the other hand, American legal culture characteristics are virtues of liberty and equality paradoxically shaped by the dominant conservative–formalist approach (Heifetz, 1999). In the Chinese legal culture, shaped by Confucianism, strong aversion to litigation dominates (Bu, 2015), while Kazakhs have a specific type of legal culture – legal nihilism (Akhmetov, 2012).

Some authors consider it impossible to study national legal cultures without retrospectives and a broader understanding of legal history, which explains the dominance of descriptive analysis. Thus, without explicit methodological explanations of approaches used in the study of national legal cultures, authors present their view of the state of national legal systems.

International, EU, and global legal culture

A specific group of articles addresses globalisation, internationalisation, and especially the Europeanisation of law, namely the creation of a common legal culture. Some of the key themes of these articles relate to specific international laws and their implementation, issues of integration and functioning of the EU legal system or organisation, and the conflict between national and EU laws and policies. Beyond the EU system, the authors discuss the global legal culture, a hybrid culture that requires a mix and coexistence of numerous cultural and legal traditions (Campbell, 2013;Garske, 2019).

The theoretical starting points for explaining the EU or global legal culture are diverse and rely on the conceptions of Friedman, Cotterrell, Nelken, Gibson and Caldeira, Weber, and Teubner. But the prevailing one is the definition by Bell and Legrand, according to which legal culture rests on the distinction between legal families and traditions or is equated with the law – “EU encompasses a diversity of legal cultures, that is, on a macrolevel various legal systems (national, EU law and sometimes international law) interact and – at times – overlap. On a micro-level, every jurist working with EU law has to accommodate both their own national legal cultural background and the autonomous, sui generis nature of EU law” (van Dorp and Phoa, 2018: 73). Thus, legal culture represents “the framework, or context, in which interpretation by members of the legal community of legal norms as well as situations, events or behaviours takes place” (Wallace, 1999: 399).

Despite differences in theoretical perspectives, all authors are concentrated on the structural and formal elements of legal systems and base their analyses on an internal, legal view. Thus, inspired by Nelken's idea, Bogojević (2013: 185) defines the purpose of legal culture “as a lens through which the interaction between rules and institutions” can be explained. According to this approach, the features of European legal culture are personalism (the basis of legal action is the individual, not the collective), legalism (rationality and equal legal treatment), and intellectualism (specific way of understanding law) (Wieacker, 1990). Similarly, Weiler (2011: 1) recognises “valid legal sources, interpretation of the law and argumentation by the courts” as key elements of EU legal culture.

The methodological perspective of these papers is predominantly descriptive. Only one article presents a pilot study with practitioners who participated in international trials at the International Criminal Court in the Hague, in war crime cases committed in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, and Lebanon (Jackson and M’Boge, 2013).

Legal culture in legal history

The largest group of articles mentioning legal culture in their titles deals with legal history issues. The most prevalent theme is the Chinese legal system during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Legal culture is also mentioned in articles discussing the Ottoman Empire and specific legal aspects of the reign of sultans, the development of Russian legal procedures, and the legal heritage of the Habsburg Monarchy. Furthermore, the authors consider the development of Brazilian law and legal culture in the 19th century and the specifics of the informal and formal legal regulation in 19th-century Great Plains. Besides, the articles present the peculiarities of legal regulation in the cases of the slave trade or tensions between local customs of colonised and imperial legal universalism. In addition to the legal history of a particular area, the articles depict the influence of religious dogmas interfering with legal systems. Given the variety of topics, there is great diversity regarding the geographical area that the articles cover. Describing legal particularities from Russia to America, from Islamic and Jewish to reformist influences on legal systems, the authors of the articles focus on the specific legal tradition of people and countries at a particular historical moment and location.

Although numerically superior, the articles touching upon issues of legal culture in legal history rarely define legal culture or explain how the term is being used. The authors who do deal with the concept mostly acknowledge the theoretical basis of Lawrence Friedman and define legal culture as stable patterns of legally oriented behaviour (Rubin, 2007: 280), or as general ideas, attitudes, values, and opinions (Hall, 1992: 87). But legal culture also represents the “partly meta-juristic dimension of any legal system… It deals with preconceptions of legal methods, whether applied in scholarly work or in forensic arguments or any other practical legal reasoning” (Wijffels, 2018: 156). Besides, the term encompasses the law itself, how it operates (Waley-Cohen, 1993: 331), and transcending individual experience (Javers, 2014). For the sake of these differences, Ross (1993: 33) criticises legal history scholars for using “legal culture as a catchall that can take in institutions and local practices, legal doctrines and informal norms, and values, ideas, and folk wisdom”. Other authors, like Bastian (1993), consider legal culture the best term for explaining historical legal changes precisely because of this elusiveness.

In most cases, the authors of these articles do not provide much information on the methodological approach. Only a few articles have explicitly, but very briefly, pointed to materials and procedures by which they came to findings presented (for instance,Lydon, 2007;Avrutin, 2010;Edwards, 2017). The overall conclusion from reading the papers is that the authors analysed the content of books, archive court, trial records, and other documentary evidence, while their methodological approach is based on a description.

Laws and legal proceedings in legal culture

The most heterogeneous section comprises articles dealing with various aspects of legal systems or a comparative approach to a particular legal segment. Here legal culture represents a specific legal and social environment influencing the efficacy of a particular law or procedure or evoking change in a certain legal field. Hence, the focus is on different legal aspects such as tort law, insolvency law, or criminal procedure law, while legal culture is a field or place where laws operate, an intervening variable contextualising development and performance in the legal system. An example of that approach is Giliker’s (2018: 266) article, where vicarious liability is described through different legal cultures, namely common and civil law; the European, Australasian, and Chinese legal systems; the difference between Western and Socialist societies, by comparison of the legal structures and their policy goals. In addition to laws, the analysis subjects are specific legal procedures such as dispute settlement process or dispute avoidance procedure, international arbitration, or some aspects of the legal procedure, such as oath and pledge or proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Only in a few articles do authors refer to the theoretical framework of the concept mentioned in the title (legal culture). In these cases, definitions derive from Friedman's and Nelken's conception of legal culture as opinions, customs, patterns of legally oriented behaviour (Giliker, 2018), “attitudes of the lawyers, claimants and respondents when dealing with disputes” (Mohd Danuri et al., 2015: 514), with reference to the distinction between the internal and the external (Picinali, 2009).

As for the empirical approach, there are various modes of studying legal aspects. Picinali (2009), for instance, used case analysis to discuss the implications of using proof beyond a reasonable doubt, which is bounded by the internal legal culture of lawyers and judges, as well as by the external legal culture of the jury. In order to investigate the usage of dispute avoidance procedure, Mohd Danuri et al. (2015) conducted interviews, the same method that Hafner (2011) carried out to discuss commercial arbitration. A common empirical approach is a comparative legal method by which authors analyse laws or procedures in different legal systems. One such approach is that of Butko et al. (2017), who examine the legal regulation of dignity in European countries. In this way, the articles cover a wide geographic area, from Italy, across Russia and Malaysia, to Indonesia, USA, China, etc., with a cross-national approach.

Politics and law

The last group of articles addresses the relationship between politics and law and the role of law in defining the political sphere or vice versa – the impact of politics on the legal setup. The articles discuss democracy, constitutionalism, political legitimacy, or judicial reforms influenced by democratisation from a cross-national and comparative perspective. Some papers cover more concrete legal and political issues, such as same-sex marriage, abortion, political representation, or corruption. Accordingly, legal culture represents a critical (independent) variable influencing politics and interrelationship with law and legal consequences of policy decisions. By connecting politics and law, some authors bring legal and political culture together, but there is no unique approach to explaining their connection. For Pierceson (2014), political and legal culture both influence policies, while Barzilai (1997) depicts legal culture as a part of political culture, and Garrido Gómez (2016) considers political culture a part of legal culture. Besides, legal culture is associated with another widely used concept, the rule of law. In that sense, legal culture is an indicator of the rule of law (Barzilai, 1997) or an inseparable component of a binominal rule of law/legal culture (Fonseca, 2015).

These articles rarely emphasise the meaning or sense of legal culture. In exceptional cases, the authors refer to Friedman’s and Nelken’s ideas of legal culture and what it ought to be. Thus, legal culture is defined as patterns of oriented social behaviour and attitudes towards legislation and law enforcement (Miller, 2011;Dias, 2016), or as a degree to which a community adopts the laws (Fonseca, 2015). Quite differently, in some articles, legal culture is equated with legal families or traditions and classified as the Continental law family and the Anglo-American common law family (Hytönen, 2016), or common law, civil law, and Scandinavian law (DeMichele, 2014).

From a methodological perspective, the articles are predominantly theoretical; the authors use a descriptive approach to emphasise the relations between political situations and changes influencing the legal system or specific laws. The articles that stand out in terms of their empirical research on politics and law, in which legal culture is an independent variable, use secondary data analysis (DeMichele, 2014), qualitative interviews, and focus groups (Miller, 2011).

Conclusion

The systematic analysis of scholarly articles in English containing the term legal culture in the title that are indexed in the Web of Science and Scopus databases and were published from 1955 to 2019 indicated the tendencies and the state-of-art of legal culture as a research area. The underlying question of this review was whether the papers managed to contribute to the understanding and coherence of the term.

The results lead to a paradoxical conclusion. Legal culture was initially conceived as a concept that would illuminate the relationship and interdependence between law and society, the legal system and individuals. Over the years, academic interest in and literature about legal culture have grown, and it is particularly significant today when legal systems are under scrutiny and criticism. But instead of providing a coherent explanation of the state of legal cultures, with the broad and heterogeneous understandings of the concept present in numerous articles, the concept is becoming more and more blurred.

Such a conclusion primarily stems from the number of topics that emerged from the analysed articles dealing with legal culture. Among eleven topics, the primary focus on the concept and research of legal culture was only present in the articles on theoretical and empirical approaches. Papers on other topics, which include the term legal culture in their title, used it as an independent, intervening variable, mostly as a residual category. Thus, legal culture is presented as a context, such as in the papers discussing the internationalisation of legal systems or problematising a specific law or legal procedure. For the articles concerned with legal education and those focused on popular culture, art and media, legal culture is a value and characteristic that needs to be developed at the social and individual levels. As for the papers regarding legal history and political issues, legal culture represents a legal tradition or a family, similarly to the papers on the national legal culture centred on legal systems. When it comes to the topic of legal profession, especially in the articles that talk about the local legal culture, it is a condition and working environment of those practising law.

The confusion around the concept of legal culture is even more apparent by looking at the internal coherence of the topics. Even when dealing with the same issues, researchers provide different explanations and assess disparate components as backbones of legal culture. Given the eleven thematic areas in which the articles were grouped, only the papers problematising the effect of local legal culture showed theoretical and conceptual coherence.

Topic distinction also showed that legal culture is not reserved only for the general population and legal experts, of which the theoretical and empirical articles on the professional (internal) and local legal cultures speak the most. Bearers of a recognisable legal culture are also (popular) media, legal norms and systems, and legal institutions. Thus, legal culture is becoming an explanatory variable for different relationships and conditions, by which its scientific field is expanding and becoming more heterogeneous.

Judging by the articles retrieved by this search, there are only a few theoretical clarifications or novelties in explaining legal culture. Instead of building and presenting a grounded and argued theoretical–conceptual framework, the prevailing pattern is to apply the same or slightly thematically adapted definitions of legal culture referred to in previous critical papers. On the other hand, a significant number of articles fail to explain the concept – legal culture is used as an obvious and self-explanatory term.

Regarding the methodological aspects, the analysis showed that research approaches to legal culture can be diverse and include qualitative and quantitative methods. However, there is a relatively small number of papers on the empirical research of legal culture, which mainly explore different values, attitudes, and behaviours, but also numeric data on the state of legal affairs. The prevailing approaches are the comparative legal method, especially characteristic for the articles dealing with laws and legal procedures, and the descriptive approach dominant in the papers concerning aspects of legal history. Both approaches address the substantive and structural components of the legal system, from which it is difficult to discern the characteristics of legal cultures.

Given the investigated geographical areas, the spatial orientation of the topic is apparent only in the case of articles on local legal culture. These articles deal with procedural aspects and typical court rulings in the United States. Other topics show a wide distribution and application of the concept of legal culture, but with a prevailing focus on the unique segments of national legal systems, which reduces the opportunity for comparative research.

In conclusion, the analysis indicated a number of theoretical and empirical approaches and models of applying the term legal culture in scholarly articles. Instead of a comprehensive and coherent concept, the analysis showed that legal culture is captured with too many different definitions, explanatory elements, and residual acknowledgment. Thus, it suggests that the problematic nature of the concept presented in the introduction is still present, perhaps even more pronounced, given the topicality of legal culture. It does not mean that the term is unusable or unnecessary, but it needs theoretically, conceptually and empirically grounded empowerment. In this regard, I end this paper with suggestions that I believe could improve future academic studies of legal culture.

For the sake of comprehensibility of legal culture, a clear definition and meaning researchers attach to the concept is crucial. Definitions of social phenomena certainly should not be in unison, but the failure to display a solid theoretical foundation for a concept such as legal culture in academic work is to maintain the status quo and scepticism towards its urgency and efficacy for understanding the relationship between society and law. This applies in particular to future studies that will present and use legal culture as an independent variable. It is essential to have a rationale in using the concept due to the heterogeneity of its meaning. In this regard, researchers should also pay attention to the interchangeable use of legal culture and concepts such as legal family, legal tradition, or legal system.

Future research on legal culture should build upon previous theoretical and empirical achievements, especially existing controversies over legal culture. New studies dealing with or relying on legal culture in explaining other social, legal, and political phenomena could find scientific inspiration in critical writings and offer answers and solutions. Another way of consolidating the concept is a revision of the theoretical framework and conceptualisation of legal culture according to sociological theories. With that approach, legal culture would be more oriented towards the sociology of law, within which the concept was initially conceived (Cotterrell, 2006), and which was not the case in the reviewed articles.

In addition to theoretical determination, changes in research methodology would significantly impact the explanatory power of legal culture. This analysis showed that so far legal culture has been predominantly used in considerations of individual, national, or specific sub-national phenomena. However, to build and strengthen the validity and scientific relevance, as well as the socio-legal potential, legal culture should be treated as a dependent variable in repeated and comparative research.

Thus, the full explanatory potential of legal culture when it comes to mediating the relationship between the legal system and society can be accomplished only through broader theoretical and conceptual elaborations, a clearer definition of the meaning and elements of legal culture, and diverse empirical, especially comparative research.