1 Introduction

Old maps have long been the subject of research in the fields of geography, cartography and, more recently, geoinformatics. Traditional analyses focus on aspects of their cartographic, geometric, as well as visual quality (Delano-Smith 2005,Jongepier et al. 2016,Muylle 2019). The content of old maps is an important source of information, for instance, to monitor changes and evolution of the landscape (Wilson 2005,Trachet 2018) or its settlement (Quesada-García 2022).

Most often, analyses are performed using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) or specialized software such as MapAnalyst (Jenny 2006,Weiss 2013). They usually consist of several basic steps: digitalization of the original, georeferencing and vectorization of the content of the old map (Chiang et al. 2014). The selection of a suitable method for each step involves several decisions. In the case of georeferencing it depends on the knowledge of several map properties: a number of map sheets (only one/several), projection (known/unknown), and dimensions (known/unknown). Based on mentioned map properties, the eight specific groups with different combinations of these parameters can be identified (Cajthaml 2011). Map projection and its parameters can be identified using specialized tools based on a robust mathematical apparatus (Bayer 2016). In the case of global transformations applied in georeferencing, with a number of identical points, distance residuals can be used to determine the positional accuracy of the map (Jenny et al. 2011). Among the basic methods of visualizing planimetric distortions are the display of error vectors, a distortion grid, or scale and rotation isolines (Forstner et al. 1998,Jenny et al. 2007). Creating a vector model facilitates the selection of identical points when georeferencing the map and expands the scope for applying spatial and statistical analysis of its content (Cajthaml 2010,Porter et al. 2019). On the other hand, it is very time-consuming. Efforts to automate the vectorization process focus on younger thematic and topographic maps (turn of the 19th and 20th centuries) with standardized map keys (Iosifescu at al. 2016,Zatelli et al. 2022). Subsequently, spatial statistics methods can be applied to the created model (Lelo 2020,Verbrugghe G et al. 2020).

The present paper deals with the cartographic analysis of Fabricius' map of Moravia (1569), one of the three historical lands of the Czech Republic. Using geospatial methods in a GIS environment, the paper aims to identify possible methods of its construction. It is one of the first detailed maps of smaller territorial units, the so-called chorographical maps. Their construction usually reflects the author's personal experience and varying degrees of familiarity with the area they represent. The main focus is therefore on the socio-economic elements of the map (specifically settlements), its quality, spatial and elevation distribution. The achieved results are confronted with the model of contemporary settlement structure and communication network. Its form is based on available text and map itineraries.

The selected procedure combines the various methods described above. Vectorization of the map is carried out manually and has a selective character, dealing only with the dominant component of the map (settlements). Regarding the significant positional inaccuracy, it is implemented indirectly, i.e., by identifying the settlements on the current map. In this case, vectorization did not require a georeferenced map and was done remotely with a digital image in the online catalogue. However, the quality of the digital image must meet the prerequisite of legibility of the descriptive component and cartographic content.

2 Fabricius' Map of Moravia (FMM)

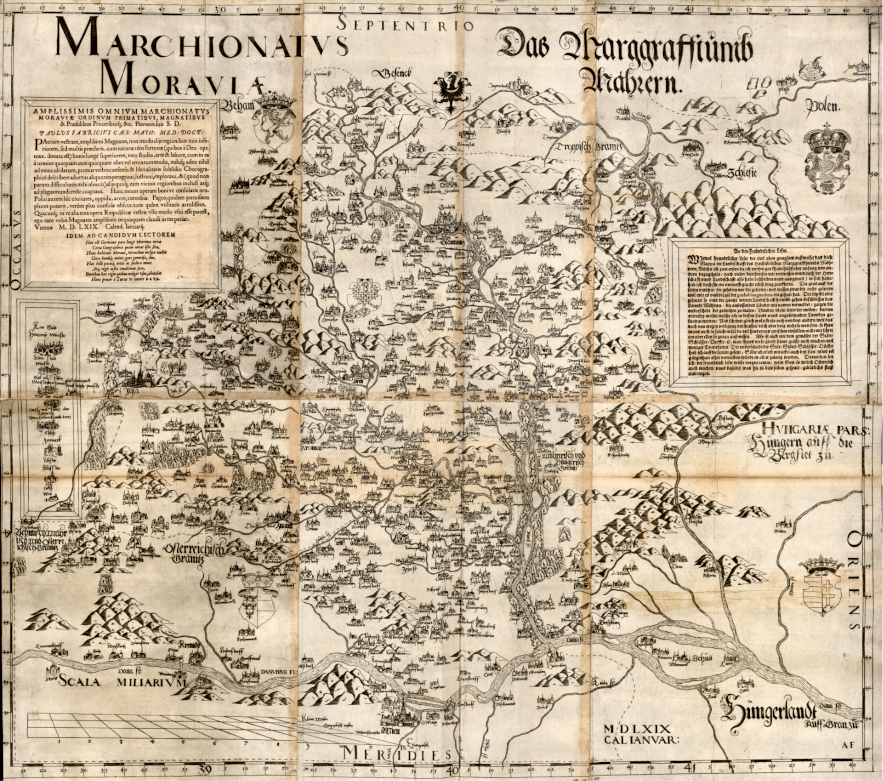

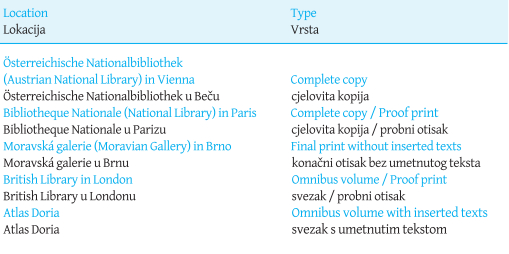

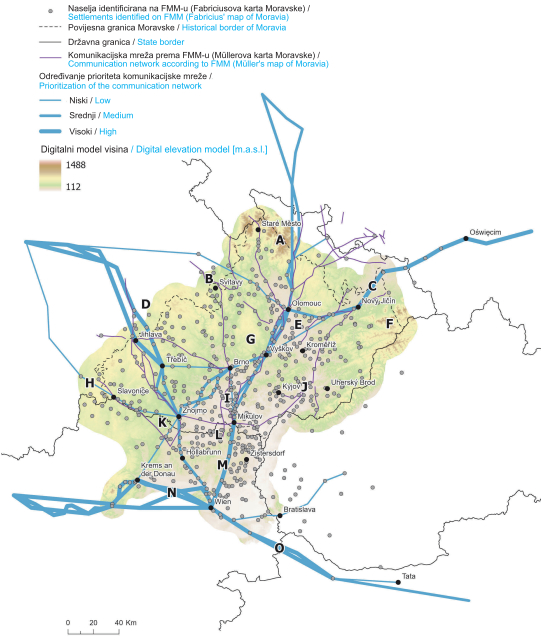

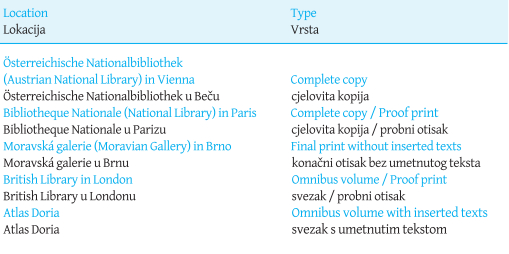

The oldest known map of Moravia was created by the humanist Paulus Fabricius (ca. 1528-1589). Born in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in southwest Poland a town of Lubáń, he established himself at the University of Vienna after studies, where he eventually grew to become Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. He later became the first court mathematician and physician to the Austrian emperors (Fröde 2010). He applied his versatile skills in many other fields, including botany, astronomy and cartography (Petz-Grabenbauer 2016,Oestmann 2014). It is documented that he prepared a concept map of Austria, the fate of which is unknown today, as well as several maps for astrolabes. Thus, his greatest cartographic achievement remains the six-sheet map of Moravia (88 x 96 cm), which was reproduced using the copperplate engraving technique (seeFig. 1). The bilingual title is placed at the top of the map field and reads: MARCHIONATVS | MORAVIÆ. - Das Marggrafftumb | Mährern. The scale of the map is approx. 1:330 000. The identity of the engraver with the AF monogram is unknown. The printing plates of the map were later stolen and therefore the author had the map engraved once more in 1575 in a reduced single sheet version. At present, only seven copies of the map can be verifiably documented (Chrást 2017). Literature mentions two other copies, but their existence and current location could not be verified. Complete copies, including an inserted printed acknowledgement and dedication to the map's readers, are documented in two copies. The other copies are either test prints or a loose omnibus volume of test and final prints (seeTable 1). The uniqueness of each copy also arises from the way in which all six sheets are connected. The problematic layout of the drawing was an issue already for the engraver, who engraved some of the settlement symbols and names on both adjacent sheets. On some copies, there is a clear auxiliary line for the trimming of the printed sheets. The resulting volume can be considered unique with different geometrical characteristics affecting, for example, the content and especially cartometric analyses (Stachoň, Chrást 2017).

Fig. 1. Fabricius' map of Moravia. Reference: ÖNB Wien: KAR K III 122363 / Slika 1. Fabricijeva karta Moravske. Izvor: ÖNB Wien: KAR K III 122363

Table 1. Known preserved copies of FMM

Three of these copies come from collector's atlases, the so-called Lafreri atlases, from the second half of the 16th century. These are the atlas of Doria, Lloyd Triestino (a copy from the Austrian National Library, seeFig. 1) and an unnamed copy from the British Library (proof print).

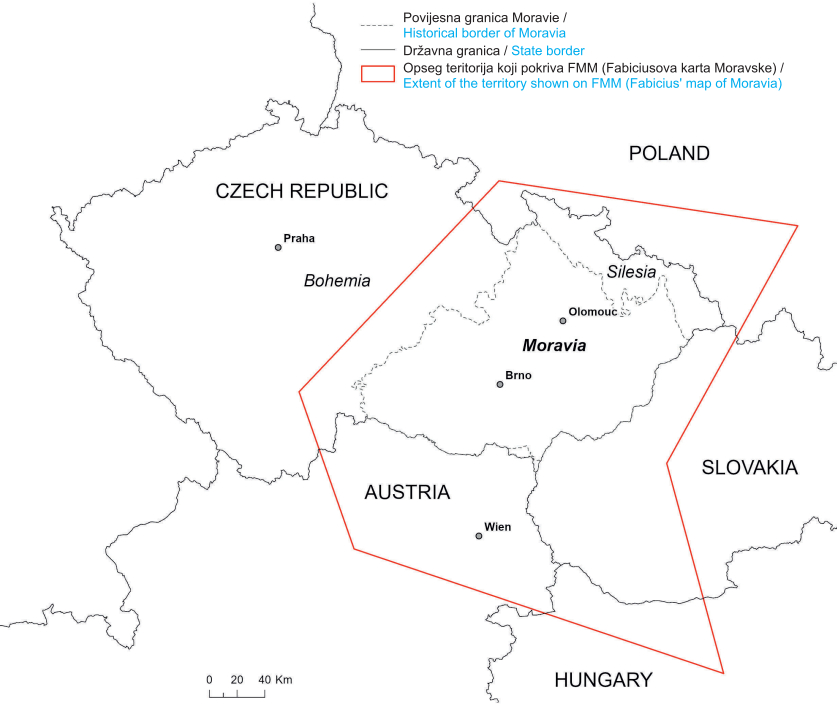

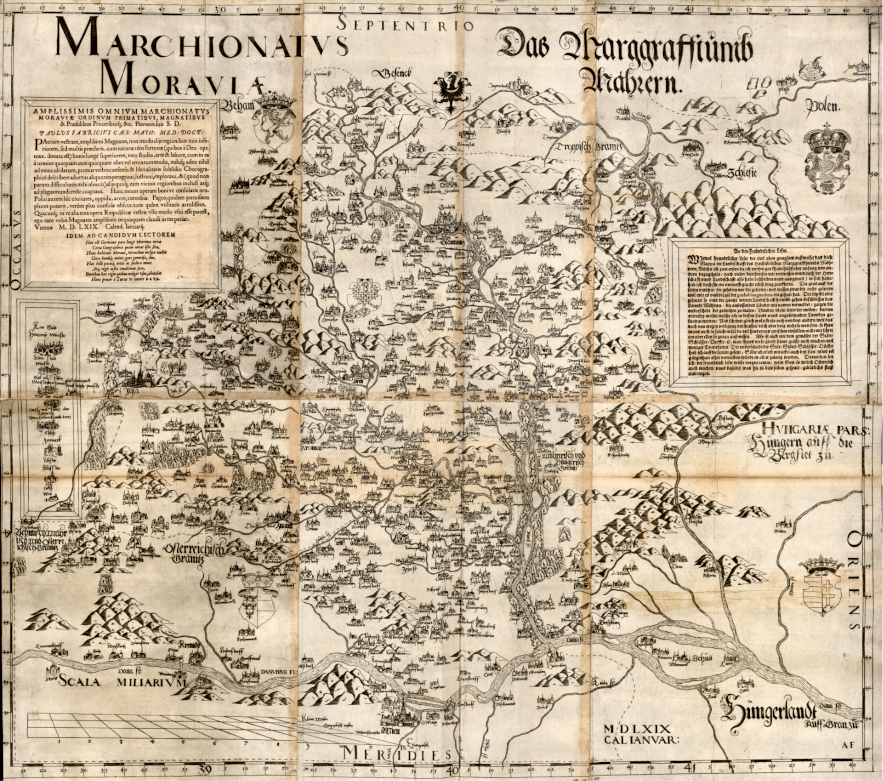

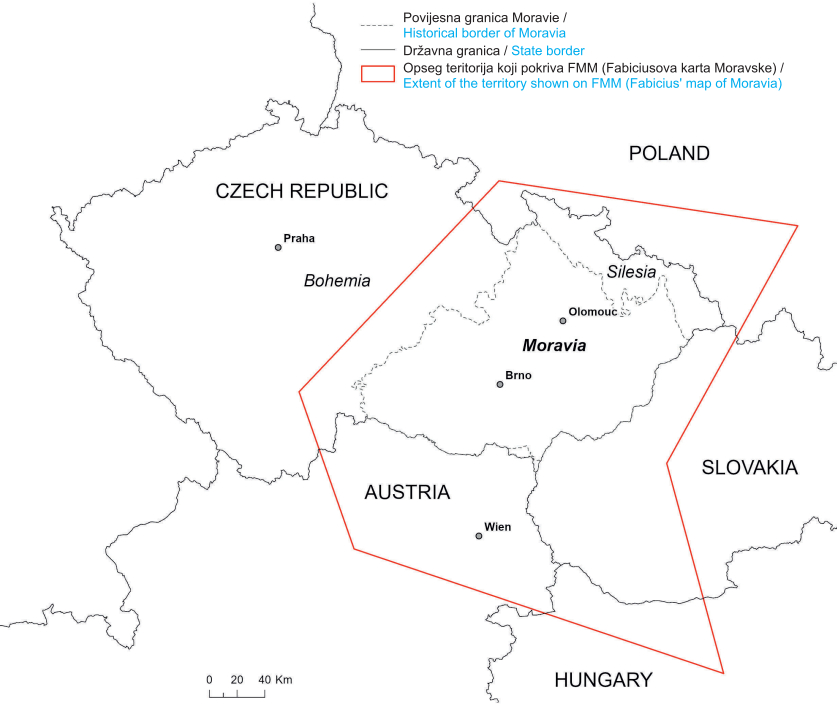

The approximate extent of the territory covered by the FMM is shown inFigure 2. Apart from Moravia, it covers a small part of the remaining two historical lands of the Czech Republic - Bohemia and Silesia[1]. The territory of Austria is also described, approximately from Vienna northwards[2], as well as parts of the present-day Slovakia, Hungary and Poland. The dominant component of the map is the settlement planimetry and its description. The German-Czech legend classifies settlements into eight categories, with some features combined on the map (e.g., town and castle). Terrain is also recorded using the hill-shading method with eastern illumination, as well as the basic river network, some still waters and landscape vegetation. The drawing of the map is decorated with depictions of land emblems. The map includes a mile scale with the length of small, geographical, Moravian, and Hungarian miles. The frame depicts a geographic grid with latitude and longitude data with 5' division.

Fig. 2. Approximate territory shown on the FMM / Slika 2. Približan teritorij prikazan na FMM-u

3 Methods of the FMM Construction

We can learn more about how the map was constructed from the author himself, whose words are recorded in the acknowledgement and dedication for the readers of the map. The author states there that he had travelled and explored the country several times. He apparently discussed his personal observations with manor owners. Indeed, it is known that he was in contact with important Moravian noblemen (e.g., Albrecht Černohorský of Boskovice), to whom he dedicated the map. He probably used local distance measurements by means of steps or worked with measuring instruments such as Jacob's staff. Determination of geographical coordinates cannot be ruled out either, with regard to his astronomical activities, but they were probably not essential for the construction of the map. Of particular note are the discrepancies between the size and orientation of the frame with the geographical raster and the content of the map. Even the proof prints do not yet contain the frame with a geographic grid. The author himself states that he positioned the map on the cardinal points, i.e., with respect to the neighbouring lands. He presumably used available geographic coordinate data to illustrate the geographic grid.

The information provided about travelling through the country can in some cases be verified from preserved archival materials. His personal knowledge of south-eastern Moravia is illustrated by a drawing of a single spring of healing water near Hluk, for which he composed an epigram during his stay at the residence of the highest provincial vice-chamberlain, Jetřich of Kunovice (ca. 1520−1582). For the royal town of Jihlava, he recommended a new town doctor. Its significance is reflected in the detailed perspective drawing, comparable only to the depictions of Vienna and Olomouc. With these mini vedutas, after all, he imitates a specific decorative trend in the cartographic work of the 16th and 17th centuries. The authenticity is sporadic with the exceptions of the aforementioned large cities and selected settlements. He named the hill Rudný, located north of Jihlava, where silver was mined, or the abandoned village of Zvonějov with the silhouette of a ruined church. All along the Vienna-Prague road. In the 1570s, he was involved in the reconstruction of the astronomical clock in Olomouc, etc. The author of the map certainly did not lack experience of travelling throughout Moravia. The question remains whether this was a systematic mapping or whether the author was only in exposed localities and used also other opportunities for topographical work. Furthermore, to what extent does this mapping contribute to the overall design and content of the map. From external sources, these could hypothetically include inventories or smaller estate maps, if they existed. As the author himself states, he has no knowledge of any predecessor who created a map of Moravia, and therefore we cannot assume borrowing of larger map templates as was the case with later maps.

4 Travel Itineraries

Three available travel itineraries were used as a source for the reconstruction of the historical communication network. The earliest of these is the map, Landstraßen-Karte „durch das Romischreych“ (hereinafter LK) from 1501 by the Nuremberg cartographer Erhard Etzlaub (ca 1460-1531/1532). The map shows important routes for pilgrims heading from the countries north of the Alps to Rome during the Holy Year of 1500. The routes from Silesia, Moravia and Bohemia pass through the area of interest towards Austria and further southwards. The second source is the Itinerarium Orbis Christiani (hereinafter IOC), which is known as the oldest travel atlas. It was written in about 1580 and its authorship is disputable. Certain is the contribution of a Flemish engraver, Frans Hogenberg (1535-1590), who printed the maps for the atlas. For the reconstruction of the network, mainly maps of Moravia (a derivative of FMM), Bohemia and Silesia were used. Maps of Austria and Hungary do not show the route plot; therefore, the map of Germania was used. The third source was the textual itinerary for German and neighbouring countries Itinerarium Germaniae Nov-antiquae (hereinafter IG) by the German scholar Martin Zeiller (1589-1661), published between 1632 and 1640.

To further refine the model of the communication network, Müller's map of Moravia from ca. 1714-1716 (hereinafter MMM) was used as a source. Johann Christoph Müller (1673−1721) was an important cartographer of the Danube countries, especially Austria, the Czech Lands, Croatia and Hungary (Lapaine et al. 2004). The MMM shows the main and minor communication routes in greater detail than the above-mentioned itineraries, even though their depiction is often fragmentary and incomplete. In some locations, there is branching into multiple sections, indicating the variability of their course.

5 Methodology

Based on the above facts, three research questions were determined:

The travel itineraries were used as an input for creation of FMM.

Settlements on FMM are not evenly distributed and the relative frequency of settlements with respect to altitude corresponds to the current situation.

The distribution of settlements identified on the FMM shows above-average densities in the areas around the communication network.

The methodology used for the research can be divided in two parts:

1. Establishment of a vector data model of the settlements identified on the FMM. Afterwards, a point layer of the existing settlement structure and a reconstructive polyline layer of the contemporary communication network were added.

2. Subsequently, spatial analyses were performed to investigate the research questions:

the comparison of the FMM content and the current situation,

density analyses of the settlement structure,

distribution of settlements in relation to hypsography.

The spatial data creation, analysis, and the preparation of statistical and map inputs was carried out in the desktop application ArcGIS Pro (2.9.0) from ESRI. First, a vector data model of FMM settlements in the WGS84 coordinate system was created and completed with the following attributes: name from the map, current name, country affiliation according to the map and according to the current state. Given the partially distorted map nomenclature (mostly German or Germanized), the identification process required comparison with other text and map sources. These usually included lexicons of towns and villages giving current and historically used Czech and German names or contemporary maps. Each settlement was assigned a reference point in the location of its historical centre (square, church, town hall, etc.). It can be assumed that these were prominent landmarks in the landscape, which the author could hypothetically use for local measuring. The settlement structure of the FMM was then subjected to a basic statistical evaluation in terms of quantity, quality (significance of settlements according to legend) and country affiliation.

In the second step, it was necessary to select a suitable dataset of existing settlements with a structure that would approximately correspond to the state at the time of the creation of the FMM and could be used as a reference source for comparative analyses. As for the Czech Republic, the necessary data is contained in the basic register RÚIAN (Registr územní identifikace, adres a nemovitostí - Registry of Territorial Identification, Addresses and Real Estate), which is maintained by ČÚZK (Český úřad zeměměřický a katastrální - State Administration of Land Surveying and Cadastre). The settlement of the Czech Republic was, with a few exceptions, completed by the end of the 16th century (Český statistický úřad 2003), and therefore the current settlement network captured by RÚIAN can be considered a suitable reference source. Data from existing municipalities, which represent the basic administrative units, would be the most suitable in the first place. A detailed assessment revealed, however, that their level of detail was insufficient, as many of them (especially larger towns) consist of several municipal districts, which, however, formed a separate settlement unit at the time of the FMM. For this reason, a point set of local municipal districts was used. Their selection is supported by the fact that their current number in Moravia (approx. 3000) corresponds approximately with the number of settlements recorded on the MMM. As for Austria, a database of administrative borders of Austria (VGD - Verwaltungsgrenzendatenbank) is available from the BEV (Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen - Federal Office of Metrology and Surveying). From the perspective of the Austrian settlement structure, the basic units are so-called “Ortschaften” (localities). These are the equivalent of the Czech municipal districts. The available polygon layer was converted to centroids using the Feature-To-Point tool[3]. The settlement structure of the border areas of the neighbouring countries, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary, was modelled using the LAU 2 (Local Administrative Units) dataset provided by EUROSTAT. Given the low number of recorded settlements in these countries on the FMM, the detail of LAU 2 is fairly sufficient. Country borders were obtained from the EUROSTAT database.

The contemporary communication network was modelled using available text and map itineraries. In the first step of vectorization, a point layer of nodes was created based on individual itineraries in the WGS84 coordinate system. By linking them, a line model of the communication network passing through the area shown on the FMM was created. Each node was provided with the information whether the location is also shown on the FMM and, if necessary, what is its significance according to the legend. Above it, a synthesis of all three source roads was made in order to get a clear overview of more and less preferred sections. The sections between major nodes were assigned a priority according to the number of passing routes.

The spatial analysis in the first step included a visual examination of the distribution and density of FMM settlements over the current map. Based on this analysis, a line schema was created replicating areas with significant concentrations of settlements, which represented the basic input for further comparison. In the second step, an analysis of the point density of both settlement models was conducted using the Point Density method[4], which is part of the Spatial Analyst extension. For each cell of the selected raster, the method calculates the ratio of the number of settlements in its vicinity to the size of this adjacent area. The cell size parameter of the output raster was set to 2.5 km, which corresponds approximately to the average size of municipalities in the Czech Republic. The shape of the adjacent area was chosen to be a circle and its radius was set to 6 km. This distance is the sum of the average distances of the nearest settlements on FMM and its standard deviation. The distance of the points was determined using the Near method[5]. Due to the irregular distribution of FMM settlements in the peripheral areas, it would have an adverse effect on the outputs of the analyses, the area of interest for the calculation was limited to a polygon encompassing the territory of Moravia and a part of Austria including a 10 km buffer zone. The density analysis was carried out for both sets of settlements and then the density ratio of the existing settlement structure depicted on the FMM was calculated using the Raster Calculator tool[6]. Using a histogram and the Natural Breaks method (Jenks), five approximately equivalent qualitative categories of density ratio were created: very low, low, medium, high and very high. Since the coverage with settlements is incomplete on FMM, the output raster of the density analysis contained null values. Such cells were marked as places with missing data (No Data) using the Set Null tool[7]. In these areas, the density data of the current settlements were visualized and examined, which were firstly standardized - through standard deviation and histogram (Natural Breaks method (Jenks)) - into five density categories: very low, low, medium, high and very high.>

The spatial analysis also worked with the elevation proportions of the investigated area. For these purposes, the European Digital Elevation Model (EU-DEM) version 1.1, a product of the European Environment Agency (EEA) COPERNICUS programme, was used as a reference source for the reading of the altitudes of the settlements in both models. Subsequently, the distribution of individual settlements in the ranges of altitude was evaluated in increments of 50 m, and the two models were compared. The DEM model also served as a source for representing the basic elevation relationships of the area depicted in the FMM.

An overview of the actual data sources used for the analyses and map visualization is provided in the following list:

State and municipal borders: Countries 2020, LAU 2020 - © EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries,

Municipal districts of municipalities in the Czech Republic: Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 - Data ArcČR © ČÚZK, ČSÚ, ARCDATA PRAHA 2022,

Database of administrative borders of Austria: Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 - Verwaltungsgrenzendatenbank (BEV),

Digital Elevation Model (EU-DEM) version 1.1 (tiles: E40N20, E40N30): Copernicus - European Environment Agency (EEA).

6 Results

The results can be divided into four parts. The first one deals with the statistical evaluation of the content of the settlement elements on FMM, the second part describes the simulated communication network, the third part presents the results of the visual analysis of the FMM settlement model, and the last one deals with the density analysis of the settlement models in relation to the communication network model and the terrain morphology.

1 Statistical evaluation of FMM content

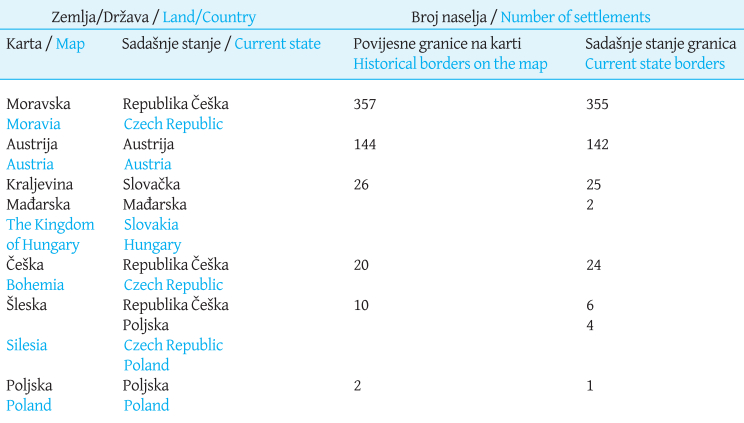

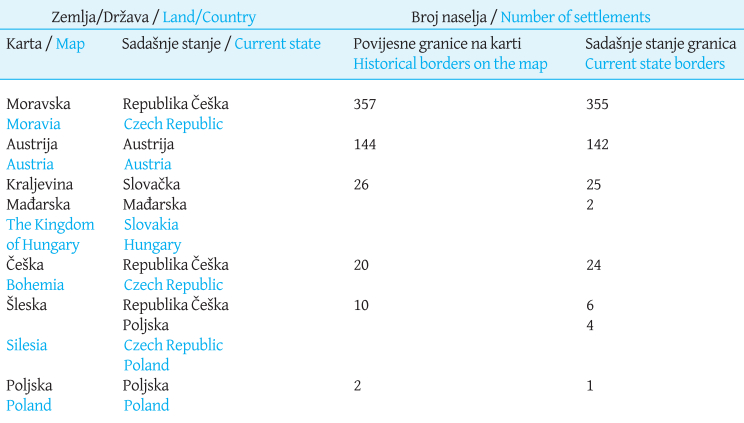

The map contains a total of 559 settlement elements. Of this number, the manorial towns of Ostrovačice and Veverská Bítýška are recorded only on the test print; they were removed from the final engraving for unknown reasons. The total also includes the castle of Hukvaldy and the ruins of the Rožnov castle, which are only mentioned by name on the map. Seven more settlements are not named (five villages and two manorial towns).Table 2 shows the content of the map in terms of land affiliation. Most settlements are depicted in Moravia (ca. 64%) and Austria (ca. 26%), followed by the Kingdom of Hungary, Bohemia, Silesia and Poland. From the perspective of present states, the depicted part of the Kingdom of Hungary is today's Slovakia and Hungary, while Silesia belongs to the Czech Republic and Poland. The differences in the number of settlements with regard to the borders on the map and current borders are the result of both incorrect localisation by the map author and changes in administrative organisation.

Table 2. Map content from the vantage point of land affiliation

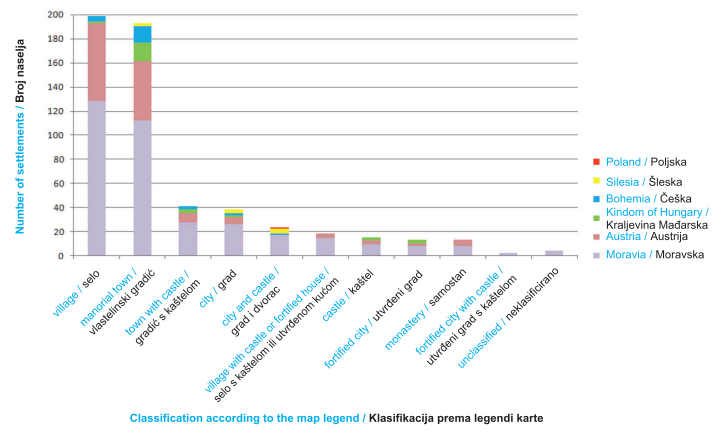

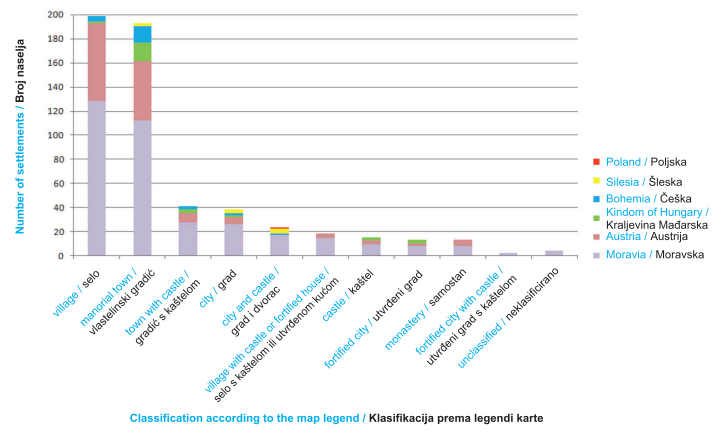

The legend distinguishes between eight categories of settlements (seeGraph 1), while the symbols for fortified towns and towns with a castle are further combined creating two more categories. The most numerous categories include villages (199) and manorial towns (193). These are mainly represented in Moravia and Austria. In the other countries, urban-type settlements prevail. In the text appendices to the map, the author states that „more villages could have been drawn, but this would have led to lack of clarity.“ It is obvious that the countries he had travelled through were mapped in greater detail, whereas in neighbouring countries he had only plotted the more important settlements.

Graph 1. Number of settlements with regard to land border displayed on FMM / Grafikon 1. Broj naselja u odnosu na granice prikazane na FMM-u

*Silesian Ostrava (called Polish Ostrava on the map) is assigned to the Silesia, although it is drawn on the map directly on the Moravia/Silesia border.

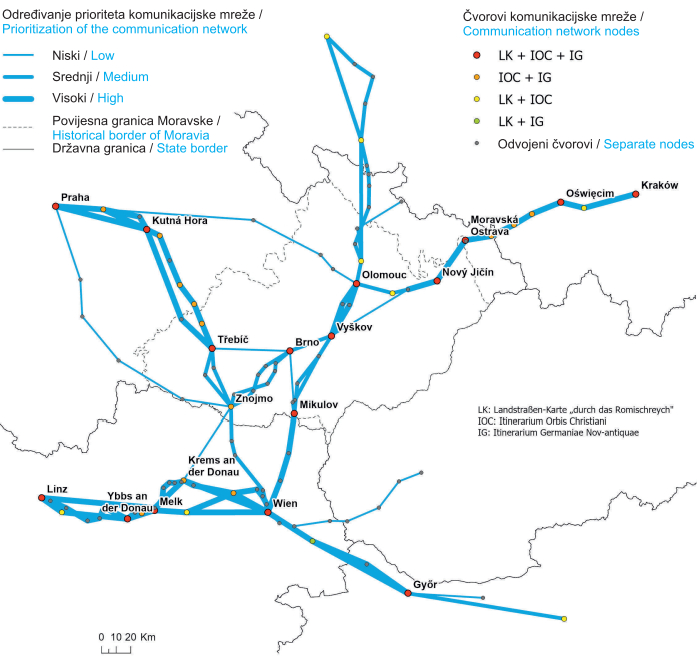

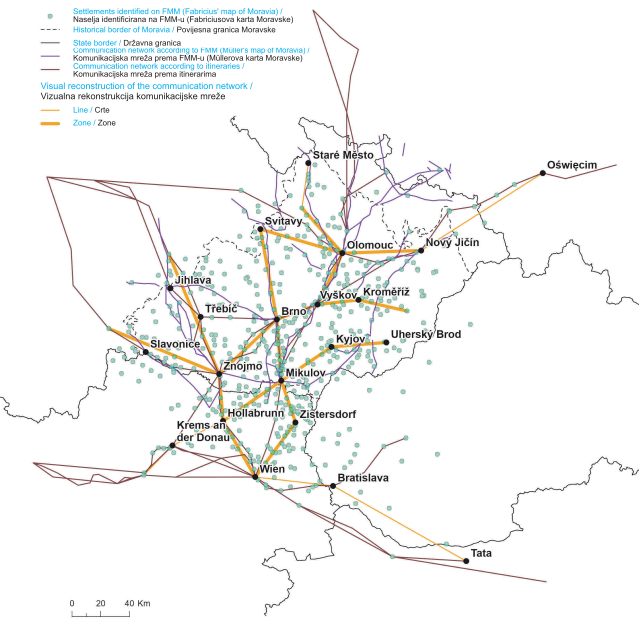

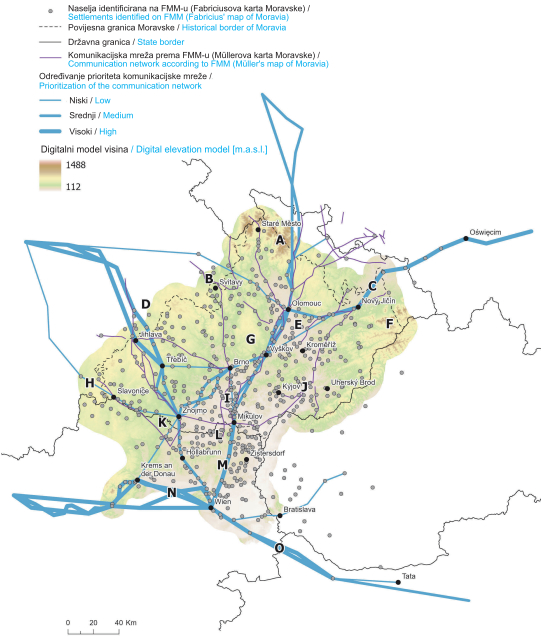

2 Synthesis of models of the contemporary communication network

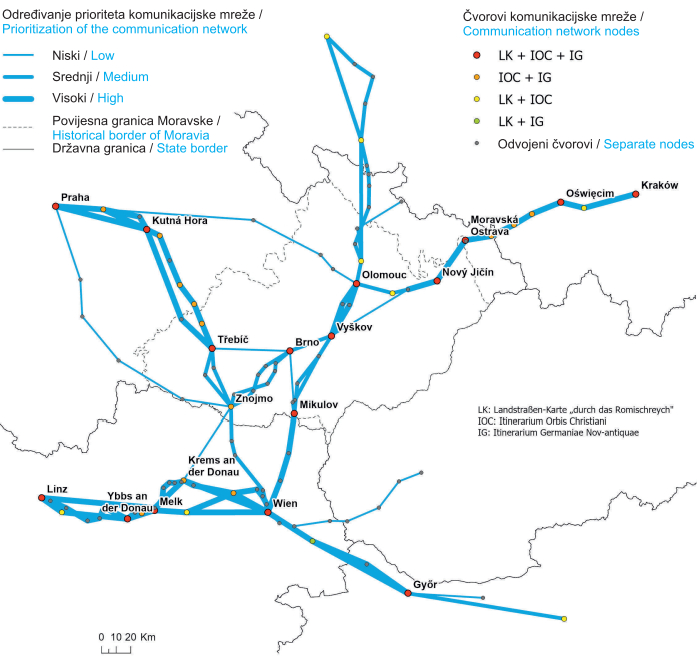

The historical communication network was studied in three timeframes, which also corresponded to its geometrical detail. The nodes which are common to all the itineraries form the main backbone of the historical communication network (seeFig. 2). With the exception of peripheral areas, they are also all recorded on the FMM, and these are generally larger towns. In Moravia, these include mainly Olomouc, Vyškov, Brno, Třebíč and Mikulov, in Austria, it is Vienna. Other nodes are located on the periphery of the area depicted on the FMM (Nový Jičín, Moravská Ostrava, Melk, Győr and Oświęcim). The main framework is completed by the towns of Krems an der Donau and, above all, Znojmo, which lies at the crossroads of several routes.Figure 3 shows the connection between Moravia and Austria and the neighbouring lands. There are three routes between Bohemia (Prague) and Moravia, connecting Moravia with Poland (Wroclaw, Kraków), Austria with Slovakia (Bratislava) and Hungary (Győr). The routes between Linz and Vienna along the Danube are also indicated. The highest priority roads described in all itineraries include the connection between Moravia and Bohemia via Třebíč, the connection between Moravia and Poland via Moravská Ostrava and the connection between Moravia and Austria via Mikulov. The connection of Moravia and Austria via Znojmo and the northern connection of Moravia and Poland have medium priority. Within Moravia, the connection of nodes often takes different paths. The situation is most evident on the routes between Znojmo and Brno, Znojmo and Třebíč, Olomouc and Vyškov, and Vyškov and Mikulov. For these routes, at least two itineraries track the road through other locations. On the other hand, the road between Brno and Mikulov has a surprisingly low priority and is replaced by the Mikulov-Vyškov connection towards Olomouc in two itineraries. High priority is given to the connection between Austria and Hungary via Győr and the connection between Vienna and Linz along the Danube, which varies considerably in different itineraries. The road passes along both the southern and northern banks of the Danube and crosses it in several places. An interesting detail of the FMM is that the map shows only three river crossings. These are the crossing of the three arms of the Danube north of Vienna, the Danube crossing at Krems an der Donau and the crossing of the southern branch of the Morava River in direction towards Olomouc.

Fig. 3. The assessment of priority routes from the communication network model / Slika 3. Procjena prioritetnih ruta iz modela komunikacijske mreže

3 Visual analysis of the FMM content

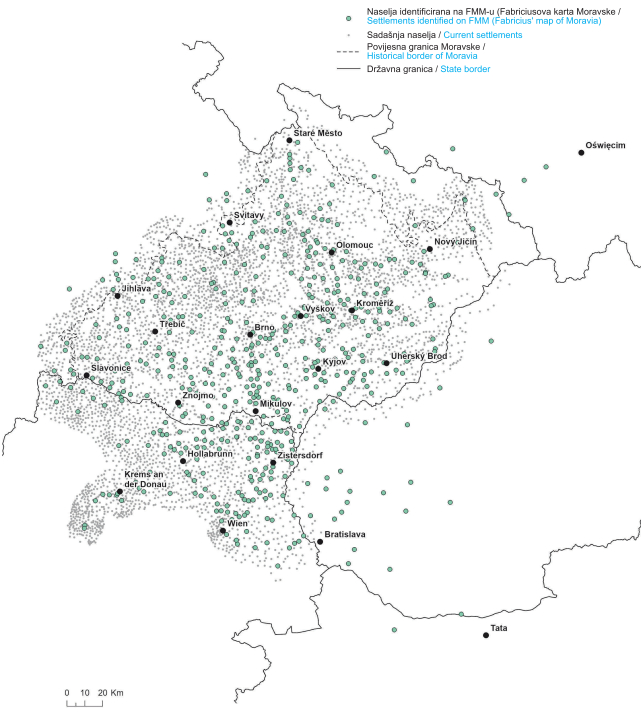

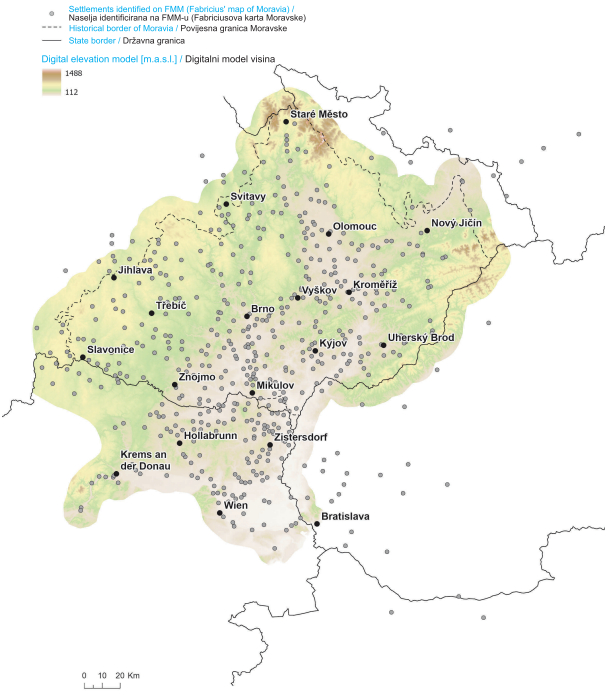

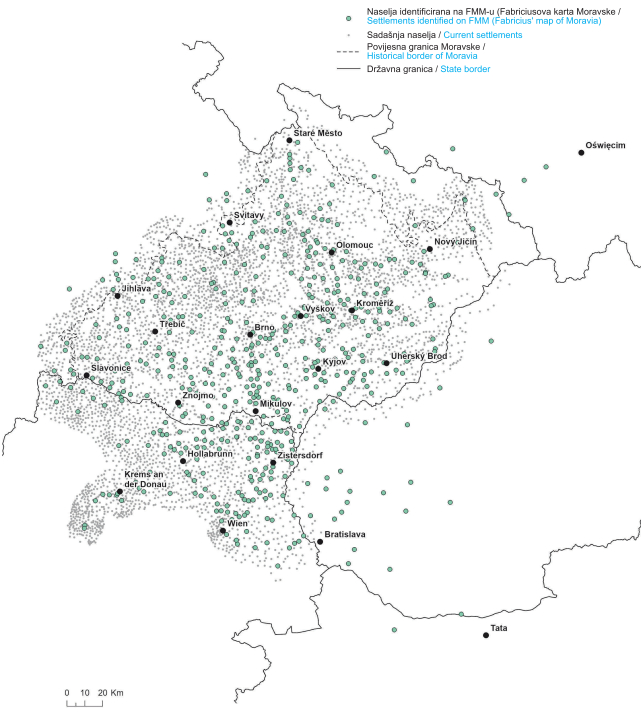

When examining the original FMM, it is difficult to objectively evaluate the equal distribution of its content. Due to the positional inaccuracy, as well as the descriptive component, hypsography and other graphic elements of the map, the content seems to be distributed quite evenly, at least in the central part of the map. The peripheral parts of the depicted area are often empty or filled with other supplementary elements or texts. By displaying the content over a current map, the approximate concentration of settlements can be revealed (seeFigure 4). In the case of Moravia, the distribution of settlements is very dispersed with higher densities in the area of southern and central Moravia. The area of Drahanská vrchovina (northeast of Brno) and the peripheral areas of northern and eastern Moravia remain practically unmapped. An exception is the sequence of settlements arranged in a north-south direction between Šumperk and Staré Město. Very few randomly distributed settlements were captured by the author in western Moravia. An interesting trend can be observed in settlements depicted in the territories of Austria. These are concentrated around Vienna, along the northern bank of the Danube towards the Melk Monastery, eastwards towards Bratislava and especially in two directions into Moravia towards Znojmo and Mikulov. Furthermore, the author recorded settlements between these two branches along the land border between Austria and Moravia and around the tri-border area of Bohemia, Moravia, and Austria. In Bohemia, there are settlements located north of Jihlava and along the north-western border (from the viewpoint of Moravia). In Slovakia, the distribution is very irregular along the northern and southern foothills of the Little Carpathians, along the Váh River (Čachtice-Považská Bystřica) and the Danube (in the area around the river island Velký Žitný ostrov). For other lands, only a few settlements are represented. In the territory of Poland, it forms a link in the direction towards Kraków. This part of the map is illustrated with a drawing of bodies of water and swamps.

Fig. 4. An overview map of settlements identified on FMM / Slika 4. Pregledna karta naselja identificiranih na FMM-u

In Moravia, the author drew only about 11% of the settlements. This situation is evident from the underlying point layer of current settlements (seeFig. 4). The other countries can only be compared visually, as only their peripheral parts are shown on the map. It is evident from the map that the author did not pay much attention to their planimetry. The settlements are located randomly, only in Austria they form the above-described clusters.

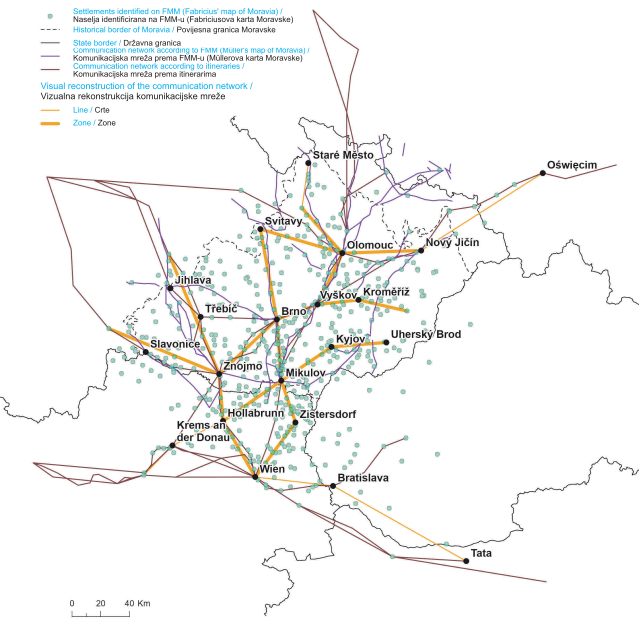

A schema showing significant concentration of settlements was produced over the FMM layer using expert estimation (seeFig. 5). For higher densities, so-called zones were outlined, and for isolated settlements, lines were drawn if their distribution had a distinguishable direction. At a glance, it is clear that some sections correspond to the model of the communication network. These include, in particular, the connections of larger Moravian towns and the connection between Znojmo and Vienna. The second route from Vienna to Moravia is, as concluded by the visual analysis, located further to the east of the road according to the itineraries. The cluster of settlements is concentrated around the line connecting Vienna, Zistersdorf, Mikulov. Based on the visual analysis, the connection between Vienna and present-day Hungary runs more in the direction of Bratislava and along the northern bank of the Danube. The visual schema differs in local details where the itineraries do not describe any route - the connection between Brno and Svitavy, Olomouc and Svitavy, Olomouc and Staré Město, the area around Kroměříž and also the line connecting Hollabrunn, Mikulov, Kyjov, and Uherský Brod. Concentrations of settlements identified by expert estimation can be more reliably explained at the local level by means of the MMM communication network. The author recorded a communication between Znojmo, Mikulov and south-eastern Moravia that continues northwards to Kroměříž. Additionally, there is a route from Olomouc northwards to Staré Město or the connection between Brno and Svitavy.

Fig. 5. Schema representing FMM settlements, communication network from visual analysis and from historical sources / Slika 5. Shema koja prikazuje naselja FMM-a, komunikacijsku mrežu iz vizualne analize i iz povijesnih izvora

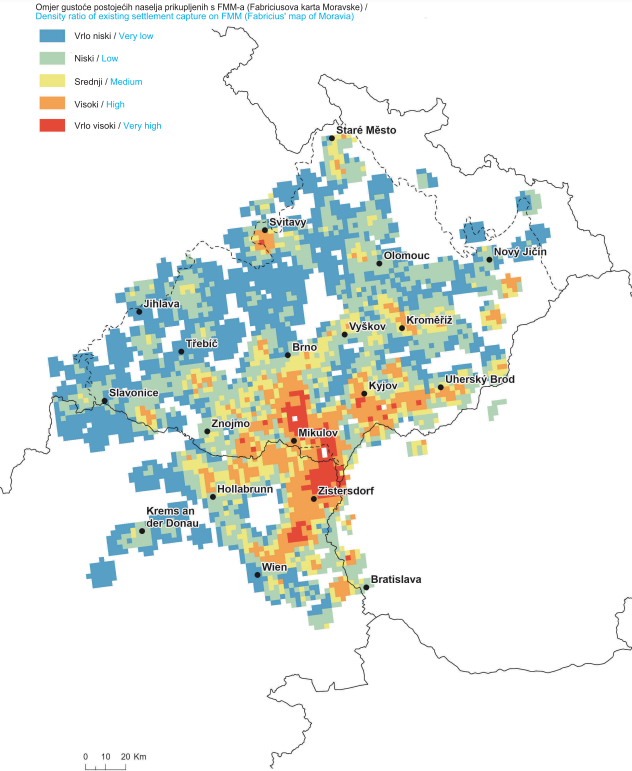

4 Density analysis of settlement models/patterns

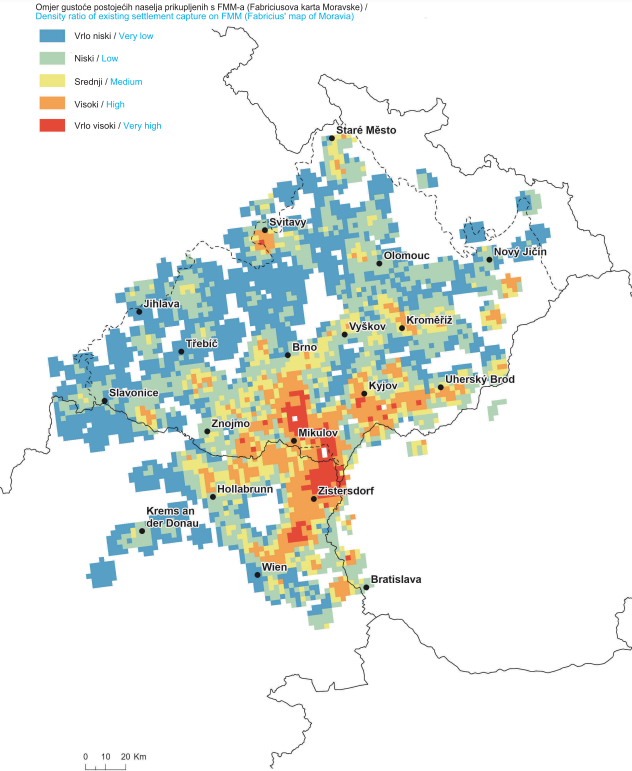

The outputs of density analyses were processed and compiled into thematic maps. As a first step, the densities of the FMM settlements and the current settlements were compared (seeFigure 6). The results of the synthesis are only available in locations covered by the FMM. As is apparent from the map, the distribution of values is considerably uneven. Along the Vienna-Brno connection passing through Zistersdorf and Mikulov, the author of the map captured the contemporary density of settlements most accurately. In some areas, he drew almost all contemporary settlements. Medium-high values are also depicted on the connecting line between Hollabrunn Austria and Uherský Brod in Moravia or on the connecting line Znojmo, Brno, Kroměříž. Other medium and higher densities are recorded as local hot spots around Svitavy, Staré Město or to the east of Kroměříž and Vienna or to the west of Znojmo. By contrast, the western part of the depicted area is characterised by a relatively wide area of lower medium and low values, which are also found in the peripheral areas of north-eastern Moravia, as well as in the area between Kroměříž and Uherský Brod.

Fig. 6. Density ratio of existing settlements captured on FMM (a high ratio indicates a relatively large number of settlements captured on the FMM compared to the current situation) / Slika 6. Omjer gustoće postojećih naselja prikupljenih s FMM-a (visok omjer ukazuje na relativno veliki broj naselja prikupljenih s FMM-a u usporedbi s trenutačnom situacijom)

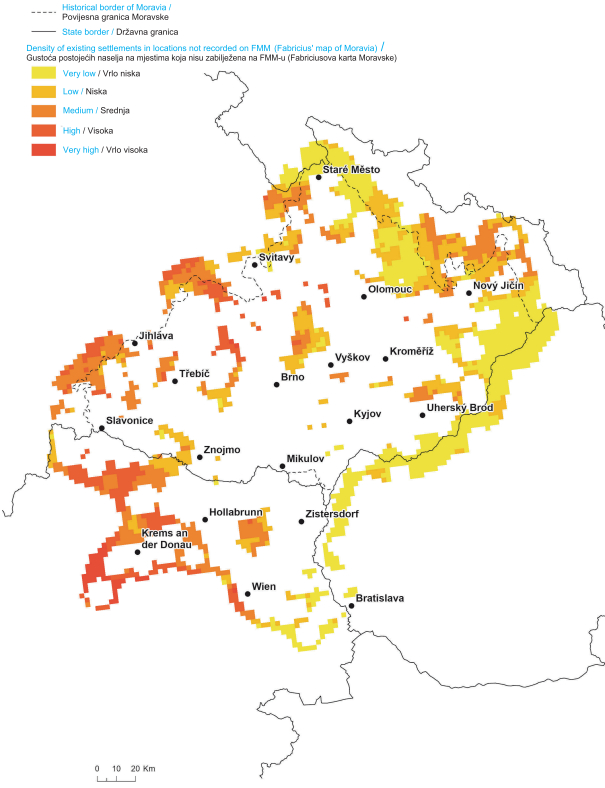

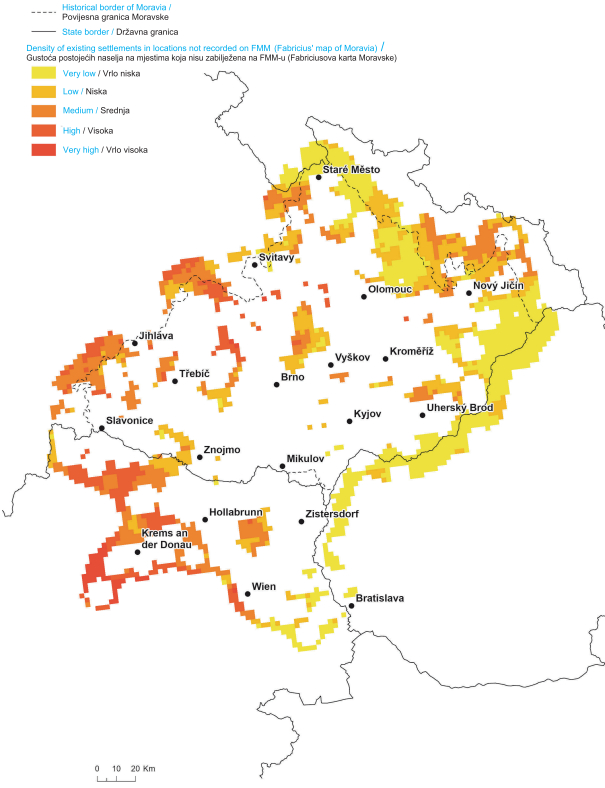

The second thematic map (seeFig. 7) portrays the opposite extreme, namely the density of settlements in areas not recorded on the FMM. The author of the map completely omitted the peripheral areas of the northern and eastern part of Moravia, i.e., the Moravian-Silesian and Moravian-Slovak borderlands, whose population density is minimal. On the other hand, along the border between Moravia and Bohemia, he mapped only selected localities. Other places with a higher population density remained out of his interest. In the central part of Moravia, he omitted some territories situated north and west of Brno. As for Austria, this includes the polygon north of Vienna and the area to the north and west of Krems an der Donau.

Fig. 7. Density of existing settlements in locations not recorded on FMM / Slika 7. Gustoća postojećih naselja na mjestima koja nisu zabilježena na FMM-u

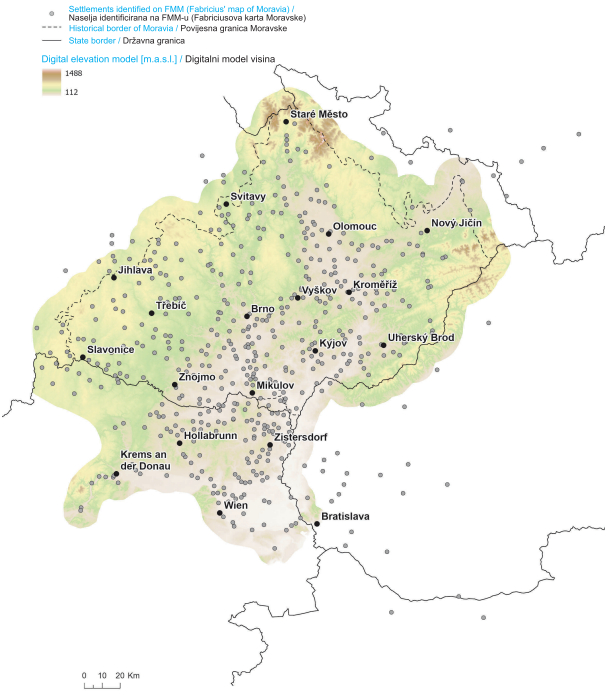

5 Analysis of the distribution of settlements in relation to elevation

The distribution of FMM settlements is highly irregular in relation to the hypsography (seeFig. 8). The author recorded mainly settlements in the lowlands and highlands. These are especially the areas of the Dyje-Svratka Valley and Upper and Lower Morava Valleys and parts of the Vienna Basin. The higher elevations of the northern and eastern Moravia are hardly mapped. The highlands in western Moravia are filled with rather randomly scattered settlements without significant concentrations.

Fig. 8. Settlements on FMM over a hypsometric map / Slika 8. Naselja na FMM-u preko hipsometrijske karte

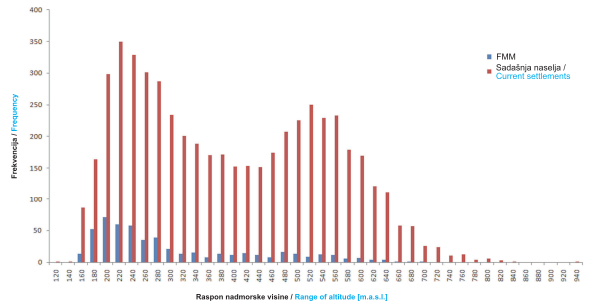

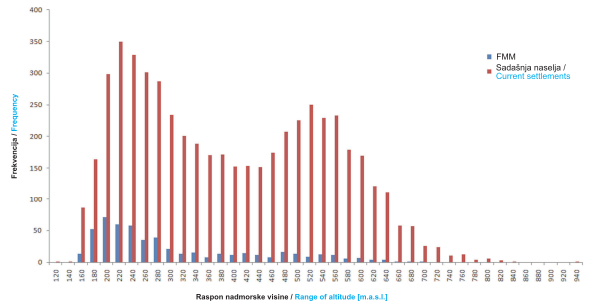

The conclusions of the hypsometric map interpretation are confirmed by the distribution of FMM settlements and current settlements by ranges of altitude (seeGraph 2). The progression of both graphs is approximately similar, with the difference that the proportion of settlements not recorded on the map grows with increasing altitude. In the case of the FMM, 60% of settlements lie at altitudes below 300 m above sea level.

Graph 2. Distribution of settlements on FMM and current settlements by ranges of altitudes / Grafikon 2. Distribucija naselja na FMM-u i sadašnjih naselja po rasponima nadmorskih visina

Furthermore, for the purpose of discussion of anomalies identified in the structure of settlements recorded on the FMM, an overview map was created where the discussed zones are marked with the letters A-O, accompanied by an elevation map and a model of the communication network (seeFig. 9).

Fig. 9. Anomalies identified in the structure of settlements on the FMM / Slika 9. Anomalije identificirane u strukturi naselja na FMM-u

7 Discussion

Anomalies in the distribution of settlements can be in many parts of the FMM explained by the proximity of the communication network, which corresponds to the documented data about author's visits to the area. This is particularly the case for locations E and I, where a significant density of settlements was detected. In some of the peripheral areas, the author recorded exclusively settlements that constitute the main stops on the historical roads mentioned in the itineraries. These areas are characterised by the absence of other settlements in their vicinity. A typical example is locality C, i.e., the connection of Moravia and Silesia through the area of Moravská brána, continuing further to Poland. A similar linear arrangement of settlements is evident in localities N and O. Interesting is the situation on the Bohemia-Moravia border, where the FMM contains settlement plotting only in localities B, D and H. This means, in the places where the main connections between the two lands passed through. No settlements are recorded in the in-between areas. These are the foothill areas of Javořická vrchovina and Žďárské vrchy, which are characterised by a concentration of mainly smaller settlements (villages). The itineraries indicate that the crossing point in locality D (Jihlava or Polná) is connected with Třebíč. In contrast, the roads captured in the 150-year-younger MMM bypass the town and only connect Jihlava with Znojmo in a more southerly direction. Moreover, their courses vary significantly locally. The MMM routes the connection between Brno and Jihlava further to the north via Velké Meziříčí and thus bypasses Třebíč. The FMM shows a concentration of settlements from Velké Meziříčí northwards to Žďár nad Sázavou or Polná instead of Jihlava. With regard to the localization of settlements on the FMM, Třebíč does not represent a significant node of the then communication network, as opposed to the itineraries and the MMM. In location B, a significant cluster of settlements was detected in the area around Svitavy, but no communication runs through it according to the itineraries. The route running north is more related to the line connecting Olomouc with eastern Bohemia. It is not until the MMM that the connection between Brno and Svitavy is recorded. The communication passes partly through Boskovická brázda and the valley of the Svitava river. In its central passage, the author of the FMM plotted settlements sparsely due to the less accessible valley of the Svitava River. Their number increases only once the border between Moravia and Bohemia is crossed. Both sources show that it is not possible to establish a fixed crossing point, since the communication network, including preferred areas (quality, safety, etc.), has constantly evolved over time. After all, the level of detail of the itineraries is a topic for further discussion.

The missing connection between Moravia and Slovakia (formerly the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary) is mainly caused by the inaccessible terrain of the border mountains White Carpathians and Beskydy (F). The author of the map recorded practically no settlements in these areas. Sporadic occurrences can be found at the foot of Beskydy Mountains, in the valleys of smaller rivers, but higher altitudes remain undescribed. Possible explanations may also be drawn from unstable religious circumstances and the risk of military attack from neighbouring Hungary. After all, even the text of the dedication of the map contains a poem at its end about the protection of the land against the Turks. In terms of low density of settlements, the situation is similar in the highest Moravian mountains - Jeseníky (A). The area around Nízký Jeseník (the southern part featuring flat uplands) remained unmapped, whereas Hrubý Jeseník (the northern mountainous part) is described at least in the vicinity of Staré Město. In the north-south direction, several settlements, mostly villages, are plotted. The striking linear character can be explained by the morphology of the terrain, which was settled mainly in the valley areas. Distances between settlements are too small to indicate possible use of itinerary data as was the case for locality C. According to the MMM, a road connecting Moravia with Kladsko passed through this area. The analysed itineraries do not mention any road here. According to the MMM, there is also a route between Olomouc and Silesia passing in two branches through Nízký Jeseník. Despite the more favourable morphological conditions in comparison to Hrubý Jeseník, the author of the FMM did not map the area in greater detail. A significant density of FMM settlements was detected in locality J. The morphology of the area is influenced by the flowing of the Morava River, it is a lowland area of the Lower-Moravian and a southern part of the Upper-Moravian Valley. The model of the communication network does not describe any communication here, however, its presence can be demonstrated using the MMM. One of its branches continues westwards along the southern slopes of the Chřiby Mountains, where the author of the FMM also located several settlements. In the southern part of the Upper Moravian Valley, neither of the sources locate any communication in the direction from Vyškov to the east. However, the detailed settlement plotting can be explained by the lowland character of the territory. According to the MMM, the communication further connects the area with southern Moravia (Mikulov) and a connection with Slovakia is recorded. The expert analysis comes to similar conclusions. The analysed itineraries describe in greater detail roads that are strategically important. The MMM also shows communications of a local significance. Although the MMM is about 150 years younger, it can be assumed from the analysed clusters that some local communication was already running through this area at the time of FMM. Another significant cluster of settlements was detected in locality L, which represents the area of the Dyje-Svratka Valley and the adjacent Austrian border region. The MMM captures a route between Znojmo and Mikulov. How the settlements are located on the Austrian side between Hollabrun and Mikulov can be explained by the lowland character of the area, which is delimited on the south by the limestone mountain range Leiser Berge, and the author's effort to connect both communication lines from Vienna to Moravia. Interesting is the empty spot on FMM between this area and the tri-border area of Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia (K). The area is characterised by inaccessible terrain of the meandering border river Dyje. It can be avoided by a detour through Znojmo, which is visible on the FMM, or by going south through the lower parts of the Granite and Gneiss Plateau. The oldest postal route connecting Vienna and Prague dating back to 1527, part of which is depicted on the MMM, passed through this area. It reached Moravia near today's Vratěnín. The last questionable zone, which was located on the basis of the analyses carried out, is marked with the letter M. The route passing between Vienna and Mikulov is an imaginary divider between the western area not described on the FMM and the eastern densely populated area, which the author of the map plotted in detail. The central part is a rather gently undulating hilly area with smaller settlements. It is obvious that the author focused his attention only on the immediate vicinity of the main roads, as shown by the settlement plotting along the Vienna-Znojmo communication. The density of settlements in the direction Vienna-Mikulov does not correspond to the routing of either of the input itineraries. The LK and IOC only mention the connection of both settlements, only the younger IG (ca. 1632-1640) positions two more stops along the route, which however lie on the western border of the FMM settlements. It is a debatable question whether the 16th-century pilgrims preferred the route closer to the Morava River, which is slightly flatter, or whether, for unknown reasons, only the author of the map preferred it. However, the IG from the early 17th century records the communication closer to the central hilly area.

8 Conclusion

Spatial analyses are currently frequently applied for extracting the thematic content of old maps. The findings of this work demonstrate that they are also helpful for detecting possible ways of construing old maps. It is necessary to select them sensitively with respect to the characteristics of the input datasets. Some interpolation methods (IDW) or methods of spatial statistics (OPTICS) did not show good results in this study due to uneven distribution and low density of settlements. The spatial analysis tools modelling point density proved to be the most suitable.

A prerequisite for the effective use of existing tools is an adequate knowledge of the original work under study, the circumstances of its creation, its historical context and the author's life. The combination of the thematic content of the map with other sources, especially the contemporary communication network, is considered to be very beneficial in the presented study.

The research answers the initial research questions:

The use of travel itineraries as an input for creation of FMM can be supported by the settlements identified in the peripheral parts of the map which correspond to them.

The spatial analysis confirmed uneven distribution of settlements on FMM and corresponding altitude distribution except of outlying areas.

The above-average densities of settlements on FMM correspond to the areas around the reconstructed communication network.

The results of the conducted analyses demonstrate a correlation between the areas with a higher density of settlements recorded on the FMM and the existence or proximity of a communication network of transregional importance. Its routing varies significantly in partial sections, whereas the location of nodes is fairly stable. Some of the observed zones with higher concentrations of settlement density can only be explained by examining earlier sources of the course of communications (MMM). Not only the quality of contemporary roads, but also the geography or morphology of the terrain influenced the level of detail in author's mapping of Moravia. While highlands were left almost unexplored, lowlands, on the other hand, are described in much greater detail. It is obvious that with regard to the scale of the map, the author performed a selective generalisation of settlements. However, it was applied subjectively, as demonstrated by the differences in the density of settlement concentration with respect to spatial and elevation aspects. Although roads as such are not plotted on the map, their existence was demonstrably determining for the quality of the field mapping. The way in which the connections between Moravia and Austria and other lands are plotted suggests that the author took information from itineraries in peripheral areas, and therefore took a systematic approach. The drawing depicting a part of Austria can be interpreted as the initial, though incomplete, effort of the author to create a separate map of Austria.

1. Uvod

Stare su karte odavno predmet istraživanja u geografiji, kartografiji, a u novije vrijeme i geoinformatici. Tradicionalne se analize usredotočuju na aspekte njihove kartografske, geometrijske i vizualne kvalitete (Delano-Smith 2005,Jongepier i dr. 2016,Muylle 2019). Sadržaj starih karata važan je izvor informacija, na primjer, za praćenje promjena i evolucije krajolika ((Wilson 2005,Trachet 2018) ili naselja (Quesada-García 2022).

Najčešće se analize izvode s pomoću GIS-a ili specijaliziranog softvera kao što je MapAnalyst (Jenny 2006,Weiss 2013). Obično se sastoje od nekoliko osnovnih koraka: digitalizacije originala, georeferenciranja i vektorizacije sadržaja stare karte (Chiang i dr. 2014). Odabir prikladne metode za svaki korak uključuje nekoliko odluka. U slučaju georeferenciranja ovisi o poznavanju nekoliko svojstava karte: broju listova karte (samo jedan/nekoliko), projekciji (poznato/nepoznato) i dimenzijama (poznato/nepoznato). Na temelju navedenih svojstava karte može se identificirati osam specifičnih skupina s različitim kombinacijama tih parametara (Cajthaml 2011). Kartografska projekcija i njeni parametri mogu se identificirati s pomoću specijaliziranih alata temeljenih na robusnom matematičkom aparatu (Bayer 2016). U slučaju globalnih transformacija primijenjenih u georeferenciranju, s nekoliko identičnih točaka, reziduali udaljenosti mogu se koristiti za određivanje položajne točnosti karte (Jenny i dr. 2011). Među osnovnim su metodama vizualizacije planimetrijskih distorzija prikaz vektora pogrešaka, distorzijska mreža ili izolinije mjerila i rotacije (Forstner i dr. 1998,Jenny i dr. 2007). Izrada vektorskog modela olakšava odabir identičnih točaka prilikom georeferenciranja karte i proširuje opseg primjene prostorne i statističke analize njezina sadržaja (Cajthaml 2010,Porter i dr. 2019). S druge strane, to oduzima puno vremena. Nastojanja da se automatizira proces vektorizacije usmjerena su na mlađe tematske i topografske karte (prijelaz iz 19. u 20. stoljeće) sa standardiziranim kartografskim ključevima (Iosifescu i dr. 2016,Zatelli i dr. 2022). Naknadno se na izrađeni model mogu primijeniti metode prostorne statistike (Lelo 2020,Verbrugghe G i dr. 2020).

Ovaj se rad bavi kartografskom analizom Fabricijeve karte Moravske (1569), jedne od triju povijesnih zemalja Češke Republike. Koristeći geoprostorne metode u GIS okruženju, u radu se žele identificirati mogući načini njezine izrade. Jedna je od prvih detaljnih karata manjih teritorijalnih cjelina, tzv. korografskih karata. Njihova konstrukcija obično odražava autorovo osobno iskustvo i različite stupnjeve poznavanja područja koje prikazuju. Stoga je glavni fokus na socioekonomskim elementima karte (posebno naselja), njezinoj kvaliteti, prostornoj i visinskoj razdiobi. Ostvareni su rezultati sučeljeni s modelom suvremene strukture naselja i komunikacijske mreže. Oblik naselja temelji se na dostupnom tekstu i kartografskim itinererima.

Odabrani postupak kombinira različite opisane metode. Vektorizacija karte obavlja se ručno i selektivnog je karaktera, a bavi se samo dominantnom komponentom karte (naseljima). S obzirom na značajnu položajnu nepreciznost, ona se provodi neizravno, tj. identifikacijom naselja na trenutnoj karti. U ovom slučaju vektorizacija nije zahtijevala georeferenciranu kartu i učinjena je na daljinu s digitalnom slikom u online katalogu. Međutim, kvaliteta digitalne slike mora ispunjavati preduvjet čitljivosti opisne komponente i kartografskog sadržaja.

2. Fabricijeva karta Moravske (FMM)

Najstariju poznatu kartu Moravske izradio je humanist Paul Fabricije (oko 1528−1589). Rođen u Donjošleskom vojvodstvu u jugozapadnoj Poljskoj, u gradu Lubáńu, nakon studija etablirao se na Sveučilištu u Beču, gdje je s vremenom postao dekan Medicinskog fakulteta. Kasnije je postao prvi dvorski matematičar i liječnik austrijskih careva (Fröde 2010). Svoje je svestrane vještine primijenio u mnogim drugim područjima, uključujući botaniku, astronomiju i (Petz-Grabenbauer 2016,Oestmann 2014). Dokumentirano je da je izradio konceptualnu kartu Austrije, čija je sudbina danas nepoznata, kao i sudbina nekoliko karata za astrolabe. Stoga je njegovo najveće kartografsko postignuće karta Moravske u šest listova (88 × 96 cm), reproducirana tehnikom bakroreza (vidisl. 1). Dvojezični naslov nalazi se na vrhu polja karte i glasi: MARCHIONATVS | MORAVIÆ. – Das Marggrafftumb | Mährern. Mjerilo karte je približno 1:330 000. Identitet gravera s monogramom AF nije poznat. Tiskarske su ploče karte kasnije ukradene pa je autor kartu dao još jednom gravirati 1575. godine na jednom listu u smanjenoj verziji. Trenutačno se može verificirati samo sedam kopija karte (Chrást 2017). U literaturi se spominju još dva primjerka, ali njihovo postojanje i sadašnje mjesto nije bilo moguće provjeriti. Potpuni primjerci, uključujući umetnutu tiskanu zahvalnicu i posvetu čitateljima karte, dokumentirani su na dvama primjercima. Ostale su kopije ili probni ispisi ili labavi svezak testnih i konačnih ispisa (viditablicu 1). Posebnost svakog primjerka proizlazi i iz načina povezivanja svih šest listova. Problematičan izgled crteža bio je izazov već za gravera koji je urezao neke od simbola naselja i imena na obama susjednim listovima. Na nekim kopijama postoji jasna pomoćna linija za obrezivanje tiskanih listova. Rezultirajući volumen može se smatrati jedinstvenim s različitim geometrijskim karakteristikama koje utječu, primjerice, na sadržaj, a posebno na kartometrijske analize (Stachoň, Chrást 2017).

Tri od tih primjeraka potječu iz kolekcionarskih atlasa, tzv. Lafrerijevih atlasa, iz druge polovice 16. stoljeća. To su atlas Doria, Lloyd Triestino (kopija iz Austrijske nacionalne knjižnice, vidisliku 1) i neimenovana kopija iz British Libraryja (probni otisak).

Približan opseg teritorija koji pokriva FMM prikazan je naslici 2. Osim Moravske pokriva mali dio preostalih dviju povijesnih zemalja Republike Češke – Češku i Šlesku[1]. Opisuje se i područje Austrije, otprilike od Beča prema sjeveru[2], kao i dijelovi današnje Slovačke, Mađarske i Poljske. Dominantna je komponenta karte planimetrija naselja i njihov opis. Njemačko-češka legenda klasificira naselja u osam kategorija s nekim na karti kombiniranim obilježjima (npr. grad i dvorac). Teren je prikazan metodom sjenčanja brda s istočnim osvjetljenjem, kao i osnovna riječna mreža, neke mirne vode i krajobrazna vegetacija. Crtež karte ukrašen je prikazima grbova zemalja. Karta sadrži mjerilo u miljama s duljinama male, geografske, moravske i mađarske milje. Okvir prikazuje geografsku mrežu s podatcima o geografskoj širini i dužini s podjelom od 5'.

3. Metode konstrukcije FMM-a

Više o tome kako je karta nastala možemo doznati od samog autora čije su riječi zapisane u zahvali i posveti čitateljima karte. Autor tamo navodi da je nekoliko puta putovao i istraživao zemlju. Očito je razgovarao o svojim osobnim zapažanjima s vlasnicima dvoraca. Doista, poznato je da je bio u kontaktu s važnim moravskim plemićima (npr. Albrechtom Černohorským iz Boskovice), kojima je posvetio kartu. Vjerojatno je koristio lokalna mjerenja udaljenosti pomoću koraka ili je radio s mjernim instrumentima kao što je Jakovljev štap. Ne može se isključiti ni određivanje geografskih koordinata s obzirom na njegove astronomske aktivnosti, ali one, vjerojatno, nisu bile bitne za izradu karte. Posebno valja istaknuti odstupanja veličine i orijentacije okvira s geografskim rasterom i sadržajem karte. Čak ni probni ispisi još ne sadrže okvir s geografskom mrežom. Sam autor navodi da je kartu postavio u odnosu na kardinalne točke, tj. u odnosu na susjedne zemlje. Vjerojatno je za ilustraciju geografske mreže upotrijebio dostupne podatke o geografskim koordinatama.

Podatci o putovanjima kroz zemlju u nekim se slučajevima mogu provjeriti iz sačuvane arhivske građe. Njegovo je osobno poznavanje jugoistočne Moravske ilustrirano crtežom jednog izvora ljekovite vode kod Hluka za koji je sastavio epigram tijekom boravka u rezidenciji najvišeg zemaljskog vicekomora Jetřicha iz Kunovica (oko 1520. – 1582.). Za kraljevski je grad Jihlavu preporučio novog gradskog liječnika. Njegovo značenje ogleda se u detaljnom perspektivnom crtežu, usporedivom samo s prikazima Beča i Olomouca. Tim mini vedutama, uostalom, oponaša specifičan dekorativni pravac u kartografskom stvaralaštvu 16. i 17. stoljeća. Autentičnost je sporadična, s izuzetkom gore navedenih velikih gradova i odabranih naselja. Nazvao je brdo Rudný, smješteno sjeverno od Jihlave, gdje se iskopavalo srebro, ili napušteno selo Zvonějov sa siluetom porušene crkve. Sve uz cestu Beč - Prag. Sedamdesetih godina 15. stoljeća sudjelovao je u rekonstrukciji astronomskog sata u Olomoucu. Autoru karte svakako nije nedostajalo iskustva putovanja po Moravskoj. Ostaje otvoreno pitanje radi li se o sustavnom kartiranju ili je autor bio samo na eksponiranim lokalitetima i koristio se i drugim prilikama za topografski rad te u kojoj mjeri to kartiranje pridonosi cjelokupnom dizajnu i sadržaju karte. Iz vanjskih izvora, to bi hipotetski moglo uključivati inventare ili manje geografske karte, ako postoje. Kako sam autor navodi, nema saznanja o bilo kojem prethodniku koji je izradio kartu Moravske, pa, stoga, ne možemo pretpostaviti posuđivanje većih kartografskih predložaka kao što je to bio slučaj s kasnijim kartama.

4. Itinerari

Kao izvor za rekonstrukciju povijesne komunikacijske mreže korištena su tri dostupna itinerara. Najranija od njih je Landstraßen-Karte „durch das Romischreych“ (u daljnjem tekstu LK) iz 1501. koju je izradio nürnberški kartograf Erhard Etzlaub (oko 1460–1531/1532). Karta prikazuje važne rute namijenjene hodočasnicima koji idu iz zemalja sjeverno od Alpa u Rim tijekom Svete godine 1500. Rute iz Šleske, Moravske i Češke prolaze kroz područje interesa prema Austriji i dalje prema jugu. Drugi izvor je Itinerarium Orbis Christiani (u daljnjem tekstu IOC), poznat kao najstariji atlas putovanja. Napisan je oko 1580. godine i njegovo je autorstvo sporno. Izvjestan je doprinos flamanskog gravera Fransa Hogenberga (1535−1590), koji je tiskao karte za atlas. Za rekonstrukciju mreže putova korištene su uglavnom karte Moravske (izvedenica od FMM), Češke i Šleske. Karte Austrije i Mađarske ne prikazuju trasu, stoga je korištena karta Germanije. Treći je izvor bio tekstualni itinerar za Njemačku i susjedne zemlje Itinerarium Germaniae Nov-antiquae (u daljnjem tekstu IG) njemačkog učenjaka Martina Zeillera (1589–1661), objavljen između 1632. i 1640. godine.

Da bi se dodatno doradio model komunikacijske mreže, kao izvor je korištena Müllerova karta Moravske iz oko 1714–1716 (u daljnjem tekstu MMM) korištena je kao izvor. Johann Christoph Müller (1673−1721) bio je važan kartograf podunavskih zemalja, posebice Austrije, Češke, Hrvatske i Mađarske (Lapaine i dr. 2004). MMM prikazuje glavne i sporedne komunikacijske pravce detaljnije od navedenih itinerara, iako je njihov prikaz često fragmentaran i nepotpun. Na nekim mjestima postoji grananje u više dijelova, što ukazuje na varijabilnost njihova toka.

5. Metodologija

Na temelju navedenih činjenica postavljene su tri istraživačke teze:

Itinerari putovanja korišteni su kao input za izradu FMM-a.

Naselja na FMM-u nisu ravnomjerno raspoređena i relativna učestalost naseljavanja s obzirom na nadmorsku visinu odgovara trenutnom stanju.

Distribucija naselja utvrđena na FMM-u pokazuje natprosječnu gustoću u područjima oko komunikacijske mreže.

Metodologija korištena u istraživanju može se podijeliti u dva dijela:

1. Uspostava vektorskog modela podataka naselja identificiranih na FMM-u na koji je potom dodan točkasti sloj postojeće strukture naselja i sloj polilinija suvremene komunikacijske mreže.

2. Kako bi se istražile postavljene teze, provedene su prostorne analize:

usporedba sadržaja FMM-a sa suvremenim stanjem

analize gustoće strukture naselja

raspodjela naselja u odnosu na hipsografiju.

Kreiranje prostornih podataka, analiza i priprema statističkih i kartografskih unosa provedena je u desktop aplikaciji ArcGIS Pro (2.9.0) tvrtke ESRI. Najprije je izrađen vektorski model podataka naselja FMM-a u koordinatnom sustavu WGS84 koji je dopunjen sljedećim atributima: ime s karte, trenutačno ime, pripadnost državi prema karti i prema trenutačnom stanju. S obzirom na djelomično iskrivljenu nomenklaturu karte (uglavnom njemačku ili germaniziranu) proces identifikacije zahtijevao je usporedbu s drugim izvorima teksta i karte. To su bili leksikoni gradova i sela, koji daju sadašnja i povijesno korištena češka i njemačka imena, ili suvremene karte. Svakom je naselju dodijeljena referentna točka u položaju njegovog povijesnog središta (trg, crkva, vijećnica itd.). Može se pretpostaviti da je riječ o istaknutim znamenitostima u krajoliku koje bi autor hipotetski mogao koristiti za lokalna mjerenja. Struktura naselja FMM-a potom je podvrgnuta osnovnoj statističkoj procjeni u smislu kvantitete, kvalitete (značaj naselja prema legendi) i državne pripadnosti.

U drugom je koraku bilo potrebno odabrati odgovarajući skup podataka postojećih naselja sa strukturom koja bi približno odgovarala stanju u trenutku izrade FMM-a i koja bi se u komparativnim analizama mogla koristiti kao referentni izvor. Što se tiče Češke, potrebni se podatci nalaze u osnovnom registru RÚIAN (Registr územní identifikace, adres a nemovitostí – Registar teritorijalne identifikacije, adresa i nekretnina) koji vodi ČÚZK (Český úřad zeměměřický a katastrální – Državna uprava izmjere i katastra). Naseljavanje Češke je, uz nekoliko iznimaka, dovršeno do kraja 16. stoljeća (Český statistický úřad 2003), pa se, stoga, trenutna mreža naselja koju je uhvatio RÚIAN može smatrati prikladnim referentnim izvorom. U prvom redu, najprikladniji bi bili podatci iz postojećih općina kao osnovnih administrativnih jedinica. Detaljna je procjena pokazala, međutim, da je njihova razina detalja bila nedovoljna jer se mnoge od njih (osobito veći gradovi) sastoje od nekoliko četvrti koje su u vrijeme nastanka FMM-a bile posebna naselja. Zbog toga je korišten skup lokalnih općinskih okruga. Njihov odabir podupire činjenica da njihov trenutačni broj u Moravskoj (oko 3000) približno odgovara broju naselja zabilježenih na MMM-u. Što se tiče Austrije, baza podataka o administrativnim granicama Austrije (VGD – Verwaltungsgrenzendatenbank) dostupna je u BEV-u (Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen – Savezni ured za mjeriteljstvo i geodeziju).

Iz perspektive austrijske strukture naselja osnovne su jedinice tzv. "Ortschaften" (mjesta). To su ekvivalenti čeških općinskih okruga. Dostupni je sloj poligona pretvoren u centroide s pomoću alata Feature-To-Point[3]. Struktura naselja pograničnih područja susjednih zemalja, Slovačke, Poljske i Mađarske, modelirana je upotrebom skupa podataka LAU 2 (Local Administrative Units) koji je osigurao EUROSTAT. S obzirom na mali broj zabilježenih naselja u tim zemljama na FMM-u, detalji LAU 2 sasvim su dovoljni. I granice zemalja dobivene su iz baze podataka EUROSTAT-a.

Suvremena je komunikacijska mreža modelirana upotrebom dostupnog teksta i kartografskih itinerara. U prvom je koraku vektorizacije kreiran točkasti sloj čvorova na temelju pojedinačnih itinerara u koordinatnom sustavu WGS84. Njihovim je povezivanjem nastao linijski model komunikacijske mreže koja prolazi područjem prikazanim na FMM-u. Svaki je čvor dobio informaciju je li lokacija prikazana i na FMM-u i, ako je potrebno, koje je njezino značenje prema tumaču znakova. Iznad nje je napravljena sinteza triju izvornih cesta kako bi se dobio jasan pregled više i manje poželjnih dionica. Dionicama između glavnih čvorova dodijeljen je prioritet prema broju prolaznih ruta.

Prostorna je analiza u prvom koraku sadržavala vizualni pregled distribucije i gustoće naselja FMM-a na trenutačnoj karti. Na temelju te analize izrađena je linijska shema koja replicira područja sa značajnom koncentracijom naselja, što je predstavljalo osnovni ulaz za daljnju usporedbu. U drugom je koraku provedena analiza gustoće točaka obaju modela naselja metodom Point Density[4] koja je dio proširenja Spatial Analysta. Za svaku ćeliju odabranog rastera metoda izračunava omjer broja naselja u njezinoj blizini i veličine tog susjednog područja. Parametar veličine ćelije izlaznog rastera postavljen je na 2,5 km, što približno odgovara prosječnoj veličini općina u Republici Češkoj.

Oblik susjednog područja odabran je kao krug, a polumjer mu je postavljen na 6 km. Ta je udaljenost zbroj prosječnih udaljenosti najbližih naselja na FMM-u i njegove standardne devijacije. Udaljenost točaka određena je metodom Near[5].. Zbog nepravilnog rasporeda naselja u rubnim područjima FMM-a to bi imalo negativan učinak na rezultate analiza. Područje interesa za računanje ograničeno je na poligon koji obuhvaća područje Moravske i dijela Austrije uključujući tampon zonu od 10 km. Analiza gustoće provedena je za oba skupa naselja, a zatim je s pomoću alata Raster Calculator[6] izračunat omjer gustoće postojeće strukture naselja prikazane na FMM-u. Histogramom i metodom Natural Breaks (Jenks) kreirano je pet približno ekvivalentnih kvalitativnih kategorija omjera gustoće: vrlo niska, niska, srednja, visoka i vrlo visoka. Budući da je pokrivenost naselja nepotpuna na FMM-u, izlazni je raster analize gustoće sadržavao vrijednosti nula. Takve su ćelije označene kao mjesta s nedostajućim podatcima (No Data) s pomoću alata Set Null[7]. U tim su područjima vizualizirani i ispitani podatci o gustoći sadašnjih naselja koji su, putem standardne devijacije i histograma (metoda prirodnih prekida (Jenks), najprije standardizirani u pet kategorija gustoće: vrlo niska, niska, srednja, visoka i vrlo visoka.

Prostorna je analiza također izrađena s visinskim proporcijama istraživanog područja. U tu je svrhu upotrijebljen European Digital Elevation Model (EU-DEM), verzija 1.1, proizvod programa COPERNICUS Europske agencije za okoliš (EEA) kao referentni izvor za očitavanje nadmorskih visina naselja u obama modelima. Potom je procijenjena distribucija pojedinih naselja u rasponima nadmorske visine u koracima od 50 m i uspoređena su dva modela. Model DEM također je poslužio kao izvor za prikaz osnovnih visinskih odnosa područja prikazanog na FMM-u.

Pregled stvarnih izvora podataka upotrijebljenih za analize i vizualizaciju karte nalazi se na sljedećem popisu:

Državne i općinske granice: Countries 2020, LAU 2020 – © EuroGeographics za administrativne granice,

Općinski okruzi općina u Republici Češkoj: Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 – Podatci ArcČR © ČÚZK, ČSÚ, ARCDATA PRAHA 2022,

Baza podataka administrativnih granica u Austriji: Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 – Verwaltungsgrenzendatenbank (BEV),

Digitalni model visina (EU-DEM), verzija 1.1 (pločice: E40N20, E40N30): Copernicus – European Environment Agency (EEA).

6. Rezultati

Rezultati se mogu podijeliti u četiri dijela. Prvi se bavi statističkom procjenom sadržaja elemenata naselja na FMM-u, drugi dio opisuje simuliranu komunikacijsku mrežu, treći dio prikazuje rezultate vizualne analize modela FMM naselja, a posljednji se bavi analizom gustoće modela naselja u odnosu na model komunikacijske mreže i morfologiju terena.

1. Statistička procjena sadržaja FMM-a

Karta sadrži ukupno 559 elemenata naselja. Od toga su broja vlastelinski gradovi Ostrovačice i Veverská Bítýška zabilježeni samo na probnom otisku; uklonjeni su iz konačne gravure iz nepoznatih razloga. U sva su naselja uključeni dvorac Hukvaldy i ruševine dvorca Rožnov koji se na karti spominju samo imenom. Još sedam naselja nije imenovano (pet sela i dva vlastelinstva). Utablici 2 prikazan je sadržaj karte s obzirom na pripadnost pojedinoj zemlji. Najviše je naselja prikazano u Moravskoj (oko 64%) i Austriji (oko 26%), a zatim u Kraljevini Mađarskoj, Češkoj, Šleziji i Poljskoj. Iz perspektive sadašnjih država, prikazani su dio Kraljevine Mađarske današnje Slovačka i Mađarska, dok Šleska pripada Češkoj i Poljskoj. Razlike u broju naselja s obzirom na granice na karti i sadašnje granice rezultat su kako pogrešne lokalizacije autora karte, tako i promjena u administrativnoj organizaciji.

Tumač znakova razlikuje osam kategorija naselja (vidigrafikon 1), dok se znakovi za utvrđene gradove i gradove s kaštelom dalje kombiniraju u još dvije kategorije. Najbrojnije su kategorije sela (199) i vlastelinstva (193). Ona su uglavnom zastupljena u Moravskoj i Austriji. U ostalim zemljama prevladavaju naselja gradskog tipa. U tekstualnim prilozima karte autor navodi da je „moglo biti ucrtano više sela, ali bi to dovelo do smanjene čitljivosti“. Očito je da su zemlje kroz koje je prošao bile detaljnije kartirane, dok je u susjednim zemljama ucrtao samo važnija naselja.

*Šleska Ostrava (na karti se naziva Poljska Ostrava) pridružena je Šleskoj, iako je na karti nacrtana izravno na granici Moravske i Šleske.

2. Sinteza modela suvremene komunikacijske mreže

Povijesna je komunikacijska mreža proučavana u trima vremenskim okvirima, što je također odgovaralo njezinoj geometrijskoj detaljnosti. Čvorovi zajednički svim itinerarima čine glavnu okosnicu povijesne komunikacijske mreže (vidisliku 2). Osim rubnih područja, svi su (uglavnom su to veći gradovi) evidentirani na FMM-u. U Moravskoj su to Olomouc, Vyškov, Brno, Třebíč i Mikulov, a u Austriji to je Beč. Ostali se čvorovi nalaze na periferiji područja prikazanog na FMM-u (Nový Jičín, Moravská Ostrava, Melk, Győr i Oświęcim). Glavni okvir upotpunjuju gradovi Krems na Dunavu i, prije svega, Znojmo koji se nalazi na raskrižju nekoliko puteva.Slika 3 prikazuje vezu između Moravske i Austrije sa susjednim zemljama. Postoje tri rute između Češke (Prag) i Moravske koje povezuju Moravsku s Poljskom (Wroclaw, Kraków), Austriju sa Slovačkom (Bratislava) i Mađarskom (Győr). Navedene su i rute između Linza i Beča uzduž Dunava. Ceste najvišeg prioriteta, opisane u svim itinerarima, sadrže vezu između Moravske i Češke preko Třebíča, vezu između Moravske i Poljske preko Moravske Ostrave i vezu između Moravske i Austrije preko Mikulova. Veza Moravske i Austrije preko Znojma i sjeverna veza Moravske i Poljske imaju srednji prioritet. Unutar Moravske veza čvorova često ide različitim putovima. Situacija je najočitija na rutama između Znojma i Brna, Znojma i Třebíča, Olomouca i Vyškova te Vyškova i Mikulova. Za ove rute najmanje dva itinerara prate cestu kroz druge lokacije. S druge strane, cesta između Brna i Mikulova ima iznenađujuće nizak prioritet i zamijenjena je vezom Mikulov-Vyškov prema Olomoucu u dvama itinerarima. Visoki prioritet ima veza između Austrije i Mađarske preko Győra i veza između Beča i Linza uzduž Dunava koja se znatno razlikuje u različitim itinerarima. Cesta prolazi i južnom i sjevernom obalom Dunava te ga na nekoliko mjesta presijeca. Zanimljiv detalj FMM-a je da karta prikazuje samo tri riječna prijelaza. To su prijelaz triju rukavaca Dunava sjeverno od Beča, prijelaz Dunava kod Kremsa na Dunavu i prijelaz južnog rukavca rijeke Morave u smjeru prema Olomoucu.

3. Vizualna analiza sadržaja FMM-a

Pri ispitivanju izvornog FMM-a teško je objektivno ocijeniti ravnomjernu distribuciju njegova sadržaja. Zbog položajne nepreciznosti, kao i opisne komponente, hipsografije i drugih grafičkih elemenata karte, čini se da je sadržaj raspoređen prilično ravnomjerno, barem u središnjem dijelu karte. Rubni dijelovi prikazanog prostora često su prazni ili ispunjeni drugim dopunskim elementima ili tekstovima. Prikazom sadržaja preko postojeće karte može se otkriti približna koncentracija naselja (vidisliku 4). U slučaju Moravske distribucija naselja je vrlo disperzirana, s većom gustoćom na području južne i srednje Moravske. Područje Drahanská vrchovina (sjeveroistočno od Brna) i rubna područja sjeverne i istočne Moravske ostaju praktički nekartirana. Izuzetak je niz naselja raspoređenih u smjeru sjever-jug između Šumperka i Staré Město. Autor je zabilježio vrlo malo nasumično raspoređenih naselja u zapadnoj Moravskoj. Zanimljiv se trend može primijetiti u naseljima prikazanima na teritorijima Austrije. Oni su koncentrirani oko Beča, uzduž sjeverne obale Dunava prema samostanu Melk, istočno prema Bratislavi i posebno u dvama smjerovima u Moravskoj prema Znojmu i Mikulovu. Nadalje, autor je zabilježio naselja između dvaju ogranaka uzduž kopnene granice Austrije i Moravske i oko tromeđe Češke, Moravske i Austrije. U Češkoj postoje naselja smještena sjeverno od Jihlave i uzduž sjeverozapadne granice (s gledišta Moravske). U Slovačkoj je rasprostranjenost vrlo nepravilna uzduž sjevernog i južnog podnožja Malih Karpata, uz rijeku Váh (Čachtice-Považská Bystřica) i Dunav (u području oko riječnog otoka Velký Žitný ostrov). Za ostale je zemlje prikazano samo nekoliko naselja. Na području Poljske to je veza u smjeru prema Krakovu. Taj je dio karte ilustriran crtežom vodenih površina i močvara.

Autor je u Moravskoj nacrtao samo oko 11% naselja. To se vidi iz temeljnog točkastog sloja sadašnjih naselja (vidisl. 4). Ostale je zemlje moguće uspoređivati samo vizualno jer su na karti prikazani samo njihovi rubni dijelovi. Iz karte je vidljivo da se autor nije previše obazirao na njihovu planimetriju. Naselja su raspoređena slučajno, jedino u Austriji čine prije opisane klastere.

Shema koja pokazuje značajnu koncentraciju naselja izrađena je preko sloja FMM-a upotrebom stručne procjene (vidisliku 5). Za veće su gustoće iscrtane tzv. zone, a za izolirana naselja povučene su crte ako je njihov raspored imao prepoznatljiv smjer. Već je na prvi pogled vidljivo da neki dijelovi odgovaraju modelu komunikacijske mreže. Misli se tu na veze većih moravskih gradova i vezu između Znojma i Beča. Drugi pravac od Beča do Moravske nalazi se, kako je zaključeno vizualnom analizom, prema itinerarima istočnije od ceste. Skupina naselja koncentrirana je oko linije koja povezuje Beč, Zistersdorf, Mikulov. Na temelju vizualne analize veza između Beča i današnje Mađarske vodi više u smjeru Bratislave i sjevernom obalom Dunava. Vizualna shema razlikuje se u lokalnim detaljima jer itinerari ne opisuju nijednu rutu – vezu između Brna i Svitavyja, Olomouca i Svitavyja, Olomouca i Staré Města, područje oko Kroměříža i također linija koja povezuje Hollabrunn, Mikulov, Kyjov i Uherský Brod. Stručnom procjenom utvrđene koncentracije naselja moguće je pouzdanije objasniti na lokalnoj razini komunikacijskom mrežom MMM-a. Autor je zabilježio komunikaciju između Znojma, Mikulova i jugoistočne Moravske koja se nastavlja prema sjeveru do Kroměříža. Osim toga, postoji ruta od Olomouca prema sjeveru do Staré Město ili veza između Brna i Svitavyja.

4. Analiza gustoće modela/uzoraka naselja

Rezultati analize gustoće obrađeni su i stavljeni u tematske karte. Kao prvi korak, uspoređena je gustoća naselja FMM-a i sadašnjih naselja (vidisliku 6). Rezultati sinteze dostupni su samo na lokacijama koje pokriva FMM. Kao što je vidljivo iz karte, distribucija vrijednosti je znatno neravnomjerna. Uzduž veze Beč-Brno, koja prolazi kroz Zistersdorf i Mikulov, autor karte najtočnije je uhvatio suvremenu gustoću naseljenosti. Na nekim je područjima ucrtao gotovo sva tadašnja naselja. Srednje visoke vrijednosti također su prikazane na spojnoj liniji između Hollabrunna u Austriji i Uherskog Broda u Moravskoj ili na spojnoj liniji Znojmo, Brno, Kroměříž. Druge su srednje i veće gustoće zabilježene kao lokalne važne točke oko Svitavyja, Staré Města ili istočno od Kroměříža i Beča ili zapadno od Znojma. Nasuprot tome, zapadni dio prikazanog područja karakterizira relativno široko područje nižih srednjih i niskih vrijednosti, koja se također nalaze u rubnim područjima sjeveroistočne Moravske, kao i u području između Kroměříža i Uherskog Broda.

Druga tematska karta (vidisliku 7) prikazuje suprotnu krajnost − gustoću naselja u područjima koja nisu zabilježena na FMM-u. Autor karte potpuno je izostavio rubna područja sjevernog i istočnog dijela Moravske, odnosno moravsko-šlesko i moravsko-slovačko pograničje, gdje je gustoća naseljenosti minimalna. S druge je strane, uzduž granice Moravske i Češke kartirao samo odabrane lokalitete. Ostala mjesta s većom gustoćom naseljenosti ostala su izvan njegova interesa. U središnjem dijelu Moravske izostavio je neke teritorije smještene sjeverno i zapadno od Brna. Što se tiče Austrije, to uključuje poligon sjeverno od Beča i područje sjeverno i zapadno od Kremsa na Dunavu.

5. Analiza raspodjele naselja s obzirom na visinu

Distribucija naselja FMM-a vrlo je nepravilna u odnosu na hipsografiju (vidisl. 8). Autor je zabilježio uglavnom naselja u nizinskom i gorskom području. To su, posebice, područja doline Dyje-Svratka i doline Gornje i Donje Morave te dijelovi Bečke kotline. Viša uzvišenja sjeverne i istočne Moravske jedva da su kartirana. Gorje u zapadnoj Moravskoj ispunjeno je prilično nasumično raštrkanim naseljima bez značajnijih koncentracija.

Zaključke interpretacije hipsometrijske karte potvrđuje raspodjela naselja FMM-a i sadašnjih naselja po rasponima nadmorskih visina (vidigrafikon 2). Progresija obaju grafikona približno je slična, s tom razlikom što udio naselja koja nisu evidentirana na karti raste s porastom nadmorske visine. U slučaju FMM-a, 60% naselja nalazi se na nadmorskoj visini manjoj od 300 m.

Nadalje, za potrebe rasprave o anomalijama identificiranima u strukturi naselja evidentiranih na FMM-u, izrađena je pregledna karta na kojoj su razmatrane zone označene slovima A - O, popraćena visinskom kartom i modelom komunikacijske mreže (vidisliku 9).

7. Diskusija

Anomalije u rasporedu naselja mogu se u mnogim dijelovima FMM-a objasniti blizinom komunikacijske mreže, što odgovara dokumentiranim podatcima o autorovim posjetima tom području. To se posebno odnosi na lokacije E i I, gdje je uočena značajna gustoća naselja. U nekim je rubnim područjima autor zabilježio isključivo naselja koja čine glavne postaje na povijesnim cestama spomenutima u itinerarima. Ta područja karakterizira nepostojanje drugih naselja u njihovoj blizini. Tipičan je primjer lokalitet C, tj. veza Moravske i Šleske preko područja Moravská brána, nastavljajući dalje prema Poljskoj. Sličan je linearni raspored naselja vidljiv i na lokalitetima N i O. Zanimljiva je situacija na češko-moravskoj granici, gdje FMM sadrži naselja prikazana samo na lokalitetima B, D i H, to znači na mjestima gdje su prolazile glavne veze između dviju zemalja. U međuprostorima nisu zabilježena naselja. To su predplaninska područja Javořická vrchovina i Žďárské vrchy koja karakterizira koncentracija uglavnom manjih naselja (sela). Itinerari pokazuju da je prijelaz na mjestu D (Jihlava ili Polná) povezan s Třebíčem. Nasuprot tome, ceste preuzete sa 150 godina mlađeg MMM-a zaobilaze grad i povezuju Jihlavu sa Znojmom samo u južnijem smjeru. Štoviše, njihovi se tokovi značajno razlikuju lokalno. MMM vodi vezu između Brna i Jihlave dalje na sjever preko Velké Meziříčí i tako zaobilazi Třebíč. FMM pokazuje koncentraciju naselja od Velké Meziříčí prema sjeveru do Žďár nad Sázavou ili Polná umjesto Jihlave. S obzirom na lokalizaciju naselja na FMM-u, Třebíč ne predstavlja značajno čvorište tadašnje komunikacijske mreže, za razliku od itinerara i MMM-a. Na lokaciji B otkrivena je značajna skupina naselja na području oko Svitavyja, ali, prema itinerarima, kroz njega ne prolazi nikakva komunikacija. Ruta koja vodi prema sjeveru više je povezana s linijom koja povezuje Olomouc s istočnom Češkom. Tek je MMM zabilježio vezu između Brna i Svitavyja. Komunikacija dijelom prolazi kroz Boskovická brázdu i dolinom rijeke Svitave. U njegovom je središnjem prolazu autor FMM-a prorijeđeno ucrtao naselja zbog teže pristupačne doline rijeke Svitave. Njihov se broj povećava tek kad se prijeđe granica između Moravske i Češke. Oba izvora pokazuju da nije moguće uspostaviti fiksnu točku prijelaza budući da se komunikacijska mreža, uključujući preferirana područja (kvaliteta, sigurnost, itd.), neprestano razvijala tijekom vremena. Uostalom, razina detalja itinerara je tema za daljnju raspravu.