3 Scope and Methodology

The aim of the research is to determine the geometrical properties of the Adriatic Sea basin’s coastline renderings on selected graticule-equipped geographical maps and nautical charts produced in the early modern age (before the era of systematic geodetic and hydrographic surveys), according to their longitudinal and latitudinal data. The main research sample consists of three geographical maps and three nautical charts (Table 1).[3]

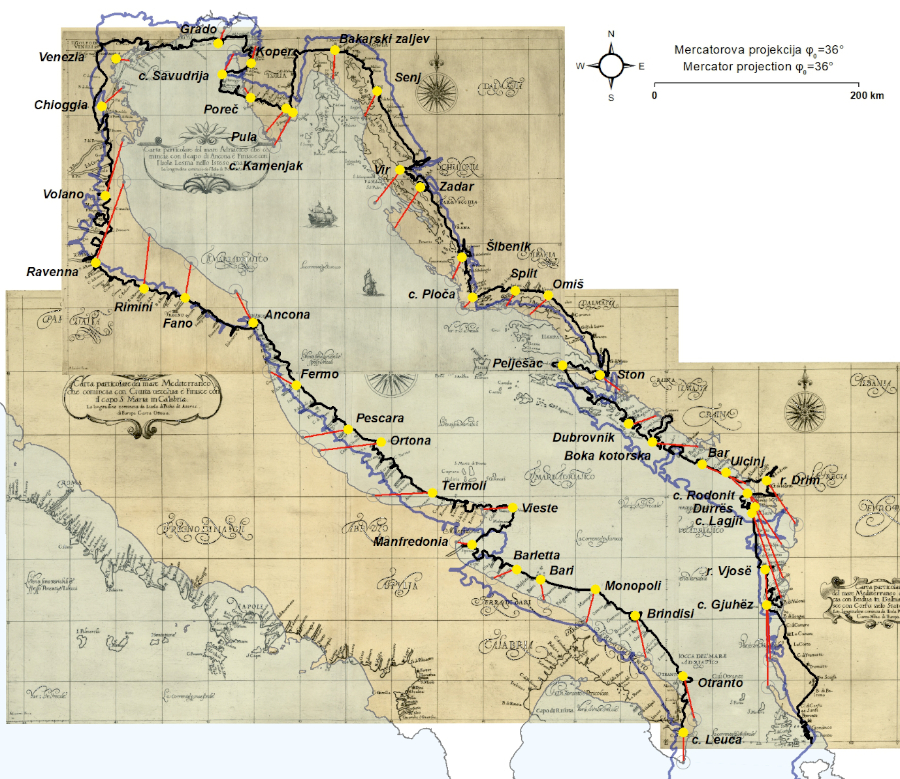

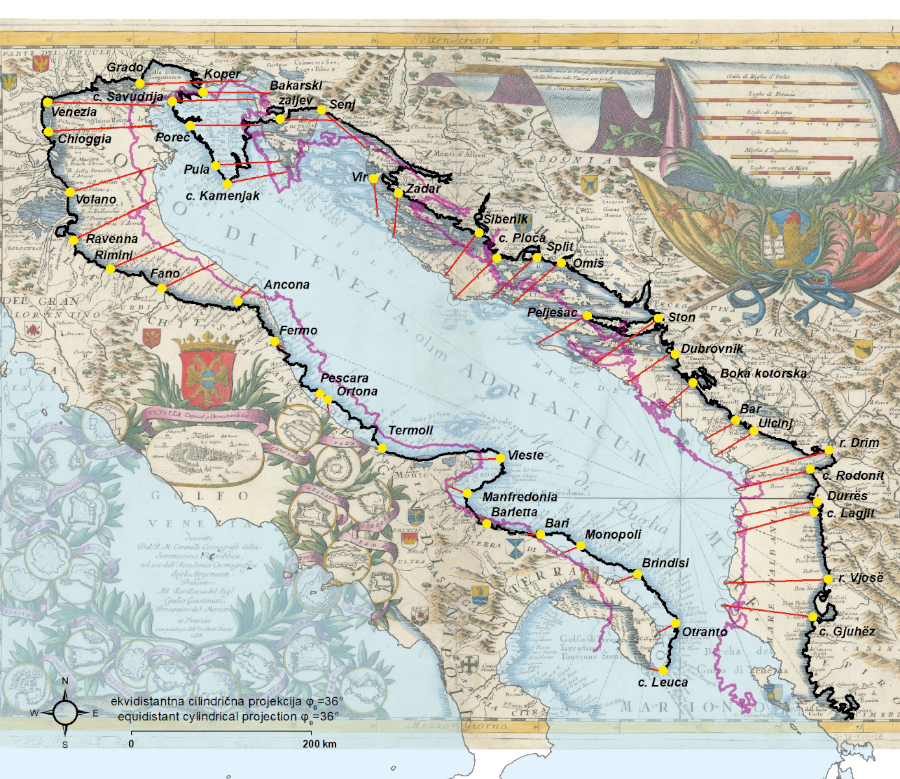

Giacomo Gastaldi’s Italiae Novissima Descriptio map (1570) is one of the earliest more detailed, and presumably more accurate early modern maps on which the Adriatic Sea and its surrounding areas are displayed. The dashes in its map frame, representing the degrees of longitude, appear to be slightly tilted and mirrored towards its central meridian, and those which represent the degrees of latitude are equally spaced, which indicates that it was intentionally made in a “Ptolemy’s first projection”. Pierre Duval’s Golfe de Venise map (1664) resembles the aesthetics of contemporary nautical charts to a certain extent, by containing a 16-point wind rose at its centre, a compass rose painted in its south-eastern part, and its spatial data focused on the coastline rendering (Figure 1), which suggests that he might have been influenced by nautical charts available at his disposal. However, even at the level of mere observation, it is noticeable that a map could not be used for navigational purposes. The first reason is its significant longitudinal “stretch”, which implies the usage of Ptolemy’s longitudinally inaccurate data on locations (Marx 2011: 36;2012: 100). The second reason is the geometry of its graticule – the LON/LAT (λ/φ) ratio of its equal-degree intervals is about 0.8, meaning that it was intentionally made in normal equidistant cylindrical projection φ0=36°, which is not conformal.[4] A similar graphical appearance of the Adriatic Sea, and an identical LON/LAT ratio of 0.8, exist on Vincenzo Maria Coronelli’s Golfo di Venezia map (1688). It also contains a wind rose, but its body of geographical data is (besides being substantially more detailed in comparison with Duval’s map) evenly distributed across its entire spatial extent (Figure 3). His map also contains several place names written in duplicates, with Hellenistic Greek names written near their Italian counterparts,[5] which implies that he, at least partly, relied on Ptolemy’s geographical data.

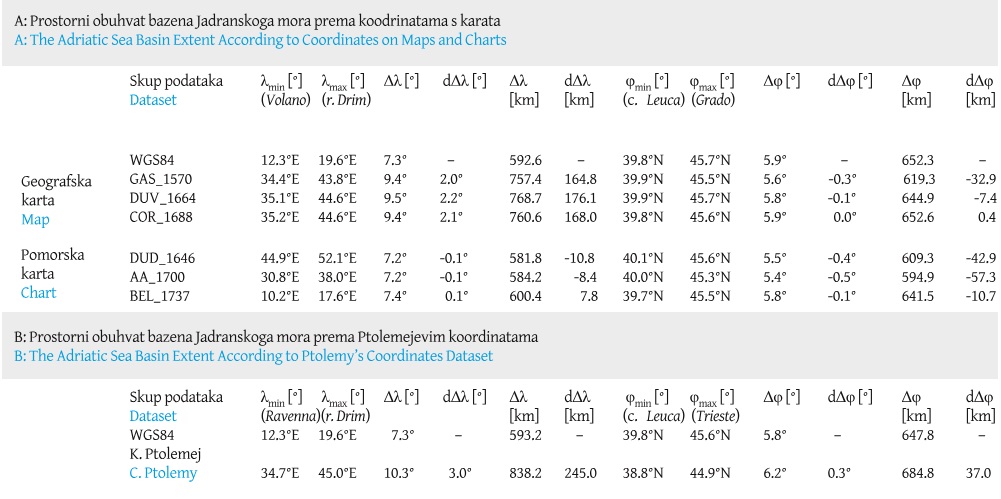

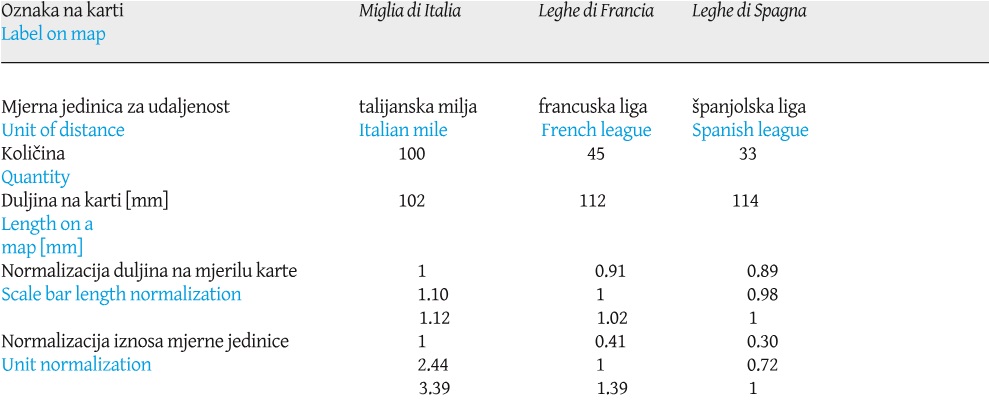

Table 1. Elementary information about the maps and charts selected as the research sample. The composite chart DUD_1646 consists of three sheets:Carta Particolare del mare Adriatico che comincia con il capo di Ancona è Finisce con L'Isola Lesina nello Isteso Mare (North Sdriatic; 708x492 mm), Carta Particolare del mare Mediterraneo che comincia con Ciuita vecchia è Finisce con il Capo S. Maria in Calabria (Central Adriatic; 755x498 mm) and Carta Particolare del mare Mediterraneo che comincia con Budua in Dalmatia è Finisce con Corfu nelo Stato Venetiano (South Adriatic; 386x519 mm). Since the Nort Adriatic sheet differs from the remaining two scale-wise, it was shrunk by 78,9% (along its both axes) to fit properly into the composite. / Tablica 1. Osnovne informacije o geografskim i pomorskim kartama upotrijebljenima u istraživanju.Kompozitna karta DUD_1646 sastavljena je od tri lista: Carta Particolare del mare Adriatico che comincia con il capo di Ancona è Finisce con L'Isola Lesina nello Isteso Mare (sjeverni Jadran; 708x492 mm), Carta Particolare del mare Mediterraneo che comincia con Ciuita vecchia è Finisce con il Capo S. Maria in Calabria (srednji Jadran; 755x498 mm) i Carta Particolare del mare Mediterraneo che comincia con Budua in Dalmatia è Finisce con Corfu nelo Stato Venetiano (južni Jadran; 386x519 mm). List s prikazom sjevernog Jadrana razlikuje se od preostala dva u mjerilu te je, u svrhu uklapanja u kompozit, umanjen na 78,9% (uzduž obje osi) svoje izvorne veličine.

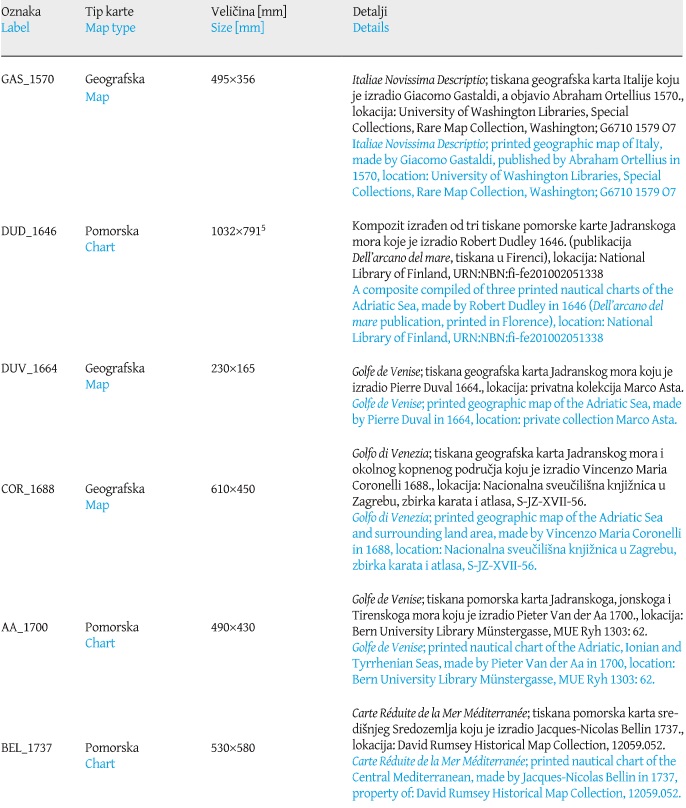

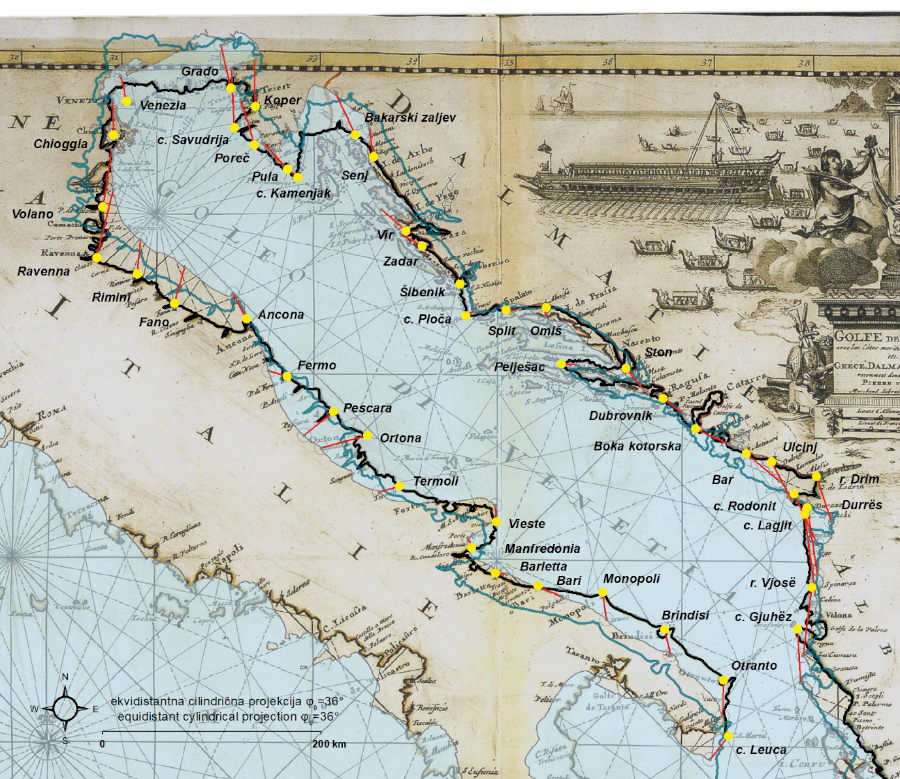

Figure 1. Residual vectors (red) of identical points (yellow) for Pierre Duval’s 1664 map, georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from the map and with the application of its proprietary E–W shift (Δλ0). The thick black line represents its vectorized coastline, while the thick semi-transparent red line represents its vectorized coastline generated upon its geometrical best-fit. Map source: private collection Marco Asta. Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 1. Vektori reziduala (crveno) identičnih točaka (žuto) na karti Pierra Duvala iz 1664., georeferenciranih upotrebom koordinata preuzetih s karte uz primjenu odgovarajućeg longitudinalnog pomaka (Δλ0). Široka crna linija predstavlja vektoriziranu obalnu crtu, dok široka poluprozirna crvena linija označava vektoriziranu obalnu crtu pri dodatnom georeferenciranju na temelju optimalnog geometrijskog podudaranja. Izvor karte: privatna kolekcija Marco Asta. Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

A sample of printed nautical charts – which were produced approximately during the same period as the selected maps and contain graticules as well – includes Robert Dudley’s three-sheet representation of the Adriatic Sea published in his book Dell’arcano del mare (1646), Pieter Van der Aa’s Golfe de Venise (1700), and Jacques-Nicolas Bellin’s Carte Réduite de la Mer Méditerranée (1737). Those three charts were already cartometrically examined to a certain extent (Marelić 2023b), but the accuracy of their spherical coordinates was not discussed in the wider context which also includes some other contemporary cartographic sources with graticules.

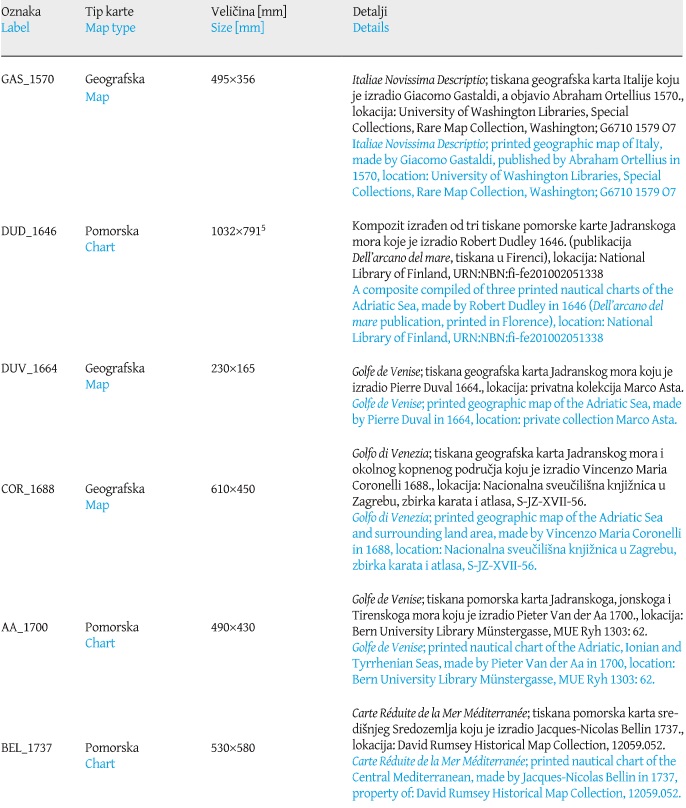

Figure 2. Residual vectors (red) of identical points (yellow) for Robert Dudley’s 1646 chart, georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from the chart and with the application of its proprietary E–W shift (Δλ0). The thick black line represents its vectorized coastline, while the thick semi-transparent blue line represents its vectorized coastline generated upon its geometrical best-fit. Chart source: National Library of Finland. Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 2. Vektori reziduala (crveno) identičnih točaka (žuto) na pomorskoj karti Roberta Dudleya iz 1464., georeferenciranih upotrebom koordinata preuzetih s karte uz primjenu odgovarajućeg longitudinalnog pomaka (Δλ0). Široka crna linija predstavlja vektoriziranu obalnu crtu, dok široka poluprozirna plava linija označava vektoriziranu obalnu crtu pri dodatnom georeferenciranju na temelju optimalnog geometrijskog podudaranja. Izvor karte: National Library of Finland. Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

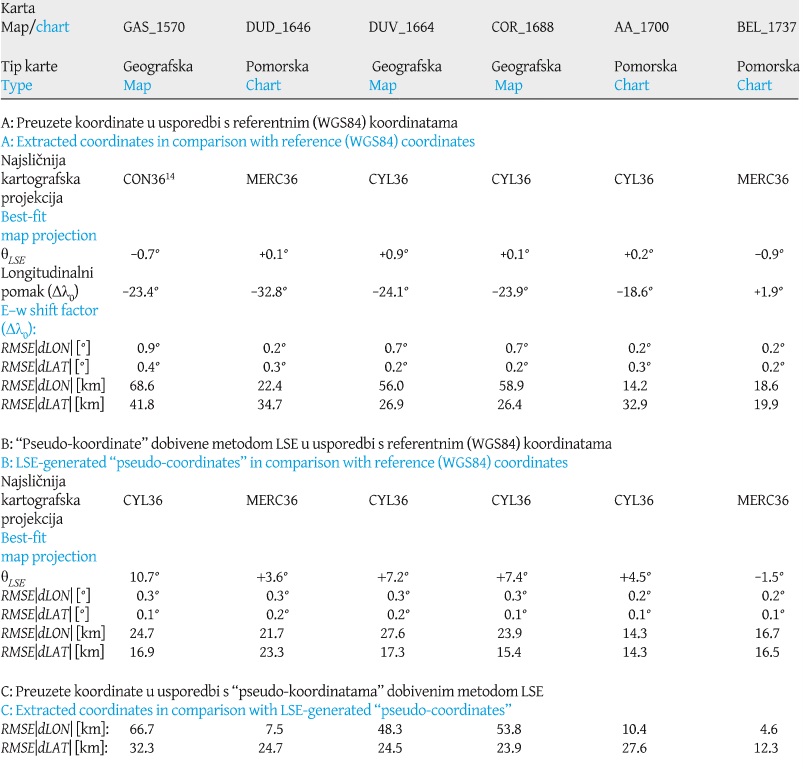

In order to examine the accuracy of selected maps and charts, they were georeferenced (subjected to LSE; the least squares estimation of residuals) in QGIS, across a standardized sample of 45 identical points per unit (representing the same 45 locations in reality, seeFigure 1–4), and with the application of Helmert transformation (Modenov and Parkhomenko 1965: 77−93) to preserve their original geometry in relative terms. Since LSE is performed in Euclidean geometry and requires a map projection to be assigned to the reference dataset[6] in advance, three map projections were selected for the task: normal equidistant cylindrical projection φ0=36° (CYL36), normal equidistant conic projection φ0=36° (CON36) and Mercator projection φ0=36° (MERC36). The former two were selected due to the selected maps’ apparent resemblance with the Hellenistic cartographical approach, while the Mercator projection was selected because it appears to be the geometrical basis of late medieval and early modern manuscript (portolan) charts, as well as the majority of early modern printed nautical charts (Loomer 1987: 144−146;Nicolai 2014: 253, 387,Marelić 2022: 98−99,2023b: 5−7).

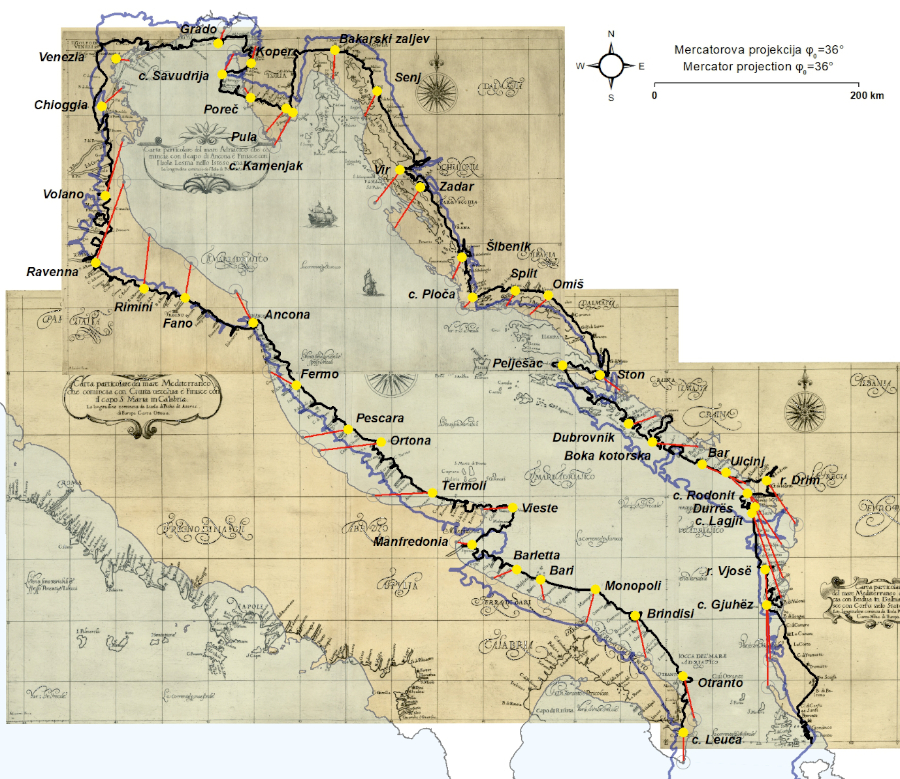

Figure 3. Residual vectors (red) of identical points (yellow) for Vincenzo Maria Coronelli’s 1688 map, georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from the map and with the application of its proprietary E–W shift (Δλ0). The thick black line represents its vectorized coastline, while the thick semi-transparent purple line represents its vectorized coastline generated upon its geometrical best-fit. Map source: Nacionalna sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu, Zbirka karata i atlasa, S-JZ-XVII-56. Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 3. Vektori reziduala (crveno) identičnih točaka (žuto) na karti Vincenza Marie Coronellija iz 1688., georeferencirane upotrebom koordinata preuzetih s karte uz primjenu odgovarajućeg longitudinalnog pomaka (Δλ0). Široka crna linija predstavlja vektoriziranu obalnu crtu, dok široka poluprozirna ljubičasta linija označava vektoriziranu obalnu crtu pri dodatnom georeferenciranju na temelju optimalnog geometrijskog podudaranja. Izvor karte: Nacionalna sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu, zbirka karata i atlasa, S-JZ-XVII-56. Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

The georeferencing of maps and charts was performed in two separate ways. The first, and merit-wise more significant for the research, is by using their proprietary LON and LAT values (manually extracted and plotted as GIS point-datasets) as “pseudo-reference points” and comparing them to their corresponding LON and LAT reference values on a WGS84 ellipsoid. The second way, in which the selected locations on charts and maps are used as identical points is purely geometric in nature and was conducted in order to determine the best-fit of their coastline renderings, regardless of the coordinates’ values assigned to them.[7] Since both scenarios yield their results in Euclidean geometry of (reference) map surface in scale 1:1 (determined by the parameters of its selected map projection), the displacements (residuals) of identical points need to be spherically corrected in addition in order to nullify their map projection-induced distortions, and their angular displacements (d |LON| [°], d| LAT| [°]) need to be transformed into geodesic distances on the WGS84 ellipsoid surface (d|LON| [km], d|LAT| [km]).[8]

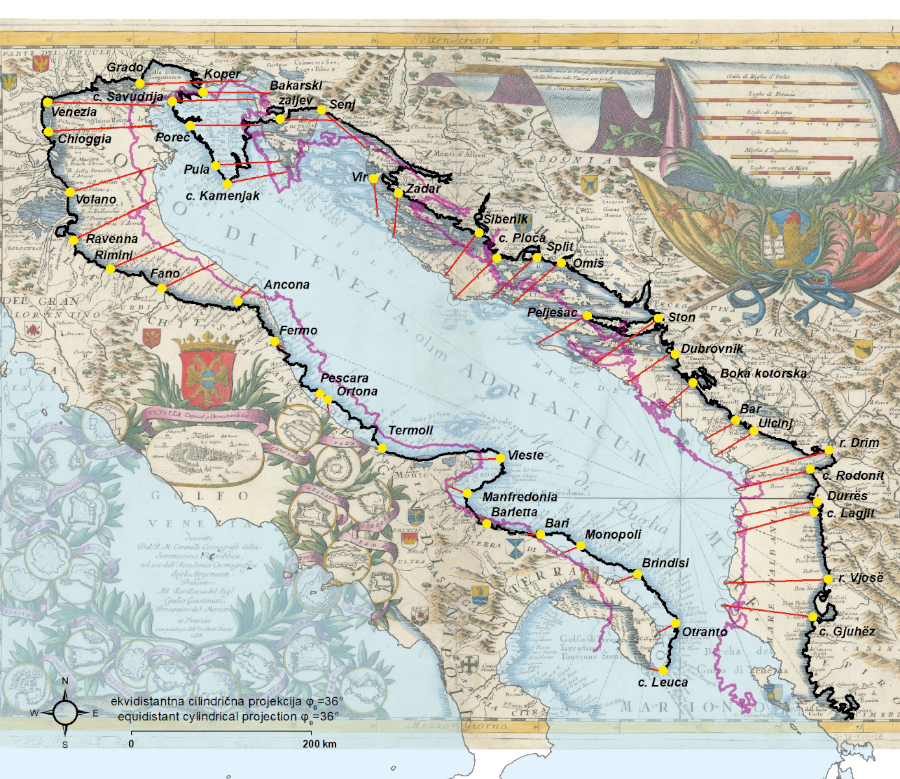

Figure 4. Residual vectors (red) of identical points (yellow) for Pieter Van der Aa’s 1700 chart, georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from the chart and with the application of its proprietary E–W shift (Δλ0). The thick black line represents its vectorized coastline, while the thick semi-transparent blue line represents its vectorized coastline generated upon its geometrical best-fit. Chart source: Bern University Library Münstergasse, MUE Ryh 1303: 62. Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 4. Vektori reziduala (crveno) identičnih točaka (žuto) na pomorskoj karti Pietra Van der Aa iz 1700., georeferenciranih upotrebom koordinata preuzetih s karte uz primjenu odgovarajućeg longitudinalnog pomaka (Δλ0). Široka crna linija predstavlja vektoriziranu obalnu crtu, dok široka poluprozirna plava linija označava vektoriziranu obalnu crtu pri dodatnom georeferenciras nju na temelju optimalnog geometrijskog podudaranja. Izvor karte: Bern University Library Münstergasse, MUE Ryh 1303: 62. Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

4 The Accuracy of Coordinates on Maps and Charts

The accuracy of spherical coordinates observed on maps and charts, and extracted as point datasets, was examined in three different analyses. The first analysis is the comparison of their proprietary longitudinal and latitudinal extents for the Adriatic Sea basin area to its corresponding extent on WGS84. The second analysis is an assessment of the accuracy of the map coordinates compared to a point-dataset extracted from the transcript of Ptolemy’s Geographike Hyphegesis (Stevenson 1991). To achieve this, 39 locations that showed higher identification reliability (Figure 5)[9] were pinpointed on maps (34 locations on GAS_1570, 32 on DUV_1664, and 38 on COR_1688 map), and extracted as point-datasets attributed with their proprietary LON and LAT values. The third analysis is the estimation of the accuracy of the coordinates extracted from maps and charts by comparing them to their reference counterparts, as well as to the “pseudo-coordinates” of their LSE-generated geometrical best-fit, obtained in parallel. In addition, certain possibilities for calculating map scale factors for longitude-wise poorly accurate map(s) are presented.

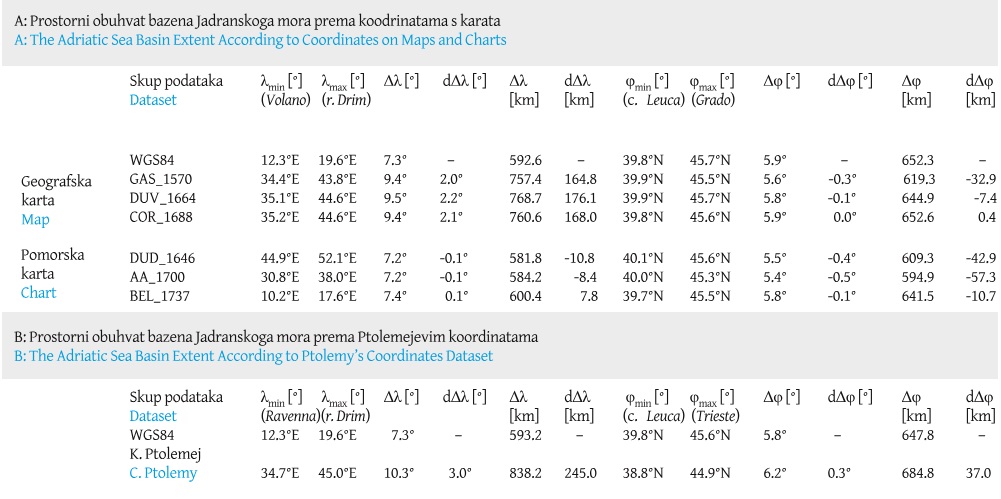

4.1 Differences in the Perceived Extent of the Adriatic Sea

The reference extent of the Adriatic Sea basin on WGS84 was measured between its longitudinal and latitudinal endpoints (Table 2). The longitudinal extent error (dΔλ) of the Adriatic Sea on maps (+2.1°, or +169.6 km on average) is significantly greater than that on charts (a fraction of a degree, or only −3.8 km on average). On the other hand, the latitudinal extent error (dΔφ) on maps (being −0.1°, or −13.3 km on average), is smaller than that on charts (−0.3°, or −37.0 km on average). Its extent, according to Ptolemy’s data, and measured between its proprietary endpoints; the mouth of river Drim – Ravenna (E–W extent), and Trieste – cape Leuca (N–S extent)[10], is the most erroneous coordinates-dataset by far, especially longitude-wise.

Table 2. Adriatic Sea basin extent derived: A: according to its longitudinal and latitudinal endpoints extracted from and 45-point dataset of identical points used to georeference maps and charts, and B: according to Ptolemy’s coordinates dataset. / Tablica 2. Prostorni obuhvat bazena Jadranskoga mora dobiven: A: iz 45 točaka korištenih za georeferenciranje karata i B: prema Ptolemejevim koordinatama.

4.2 Comparison of Maps’ Coordinates with Ptolemy’s Data

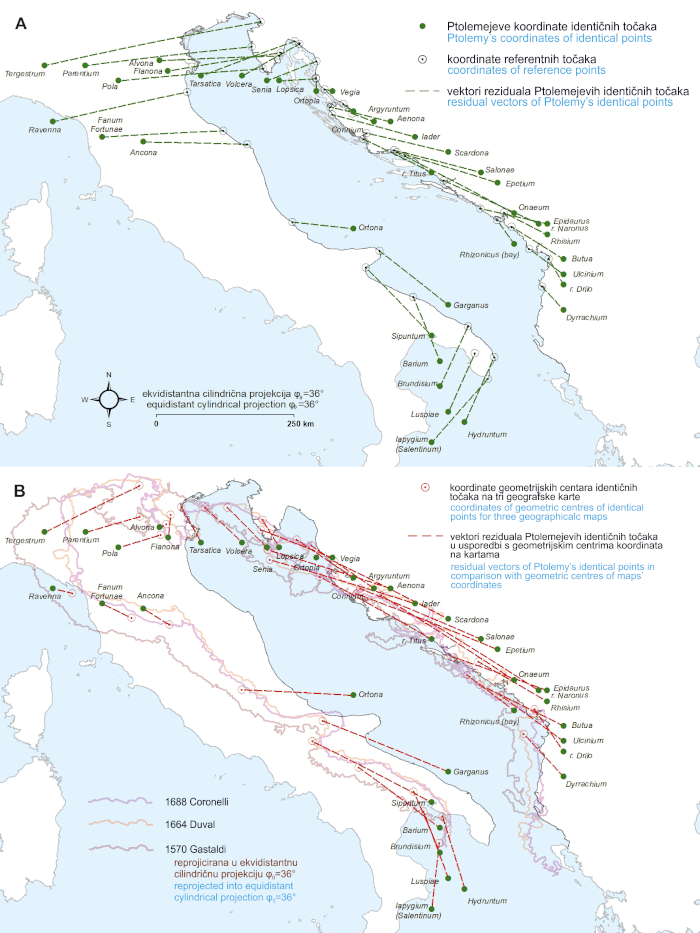

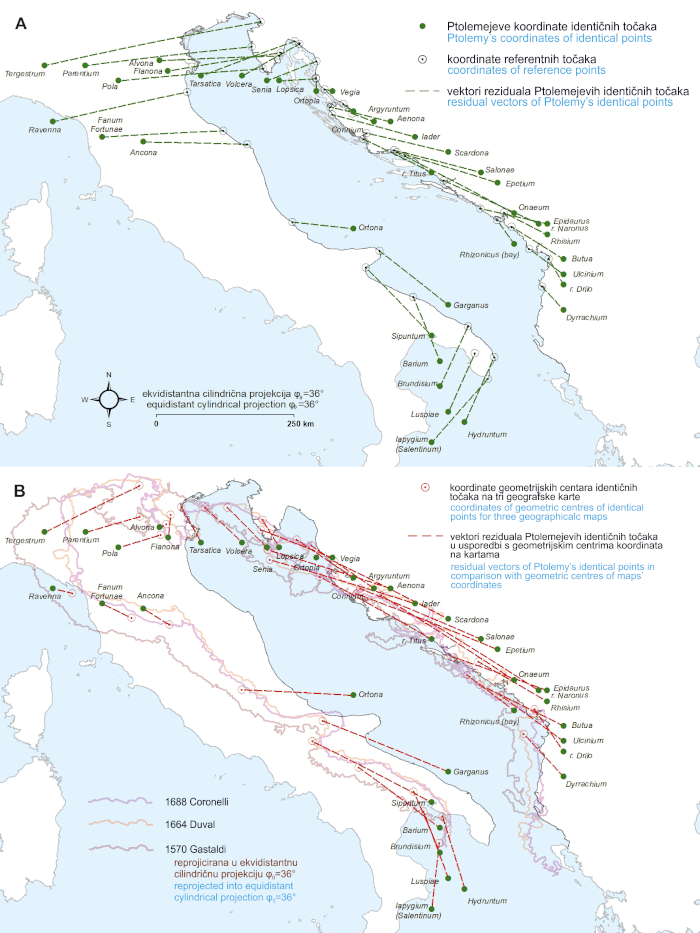

The longitude values, with regards to their display on all three selected maps, seem to be very similar to one another, as well as to Ptolemy’s coordinates. For example, the longitude of Ravenna (λ=12.3°E on WGS84) is λ=34.7°E in Ptolemy’s dataset, λ=34.9°E on Gastaldi’s map (1570), λ=35.1°E on Duval’s (1664) map, λ=35.2°E on Coronelli’s (1688) map. Ptolemy’s dataset was (in order to perform the correction of its prime meridian) longitudinally (E–W) shifted by Δλ=−25.2°, which corresponds to the longitude of Santa Antão; the westernmost island of the Cape Verde archipelago – an adjustment which was previously applied by Marx in his quantitative analysis of Ptolemy’s coordinates for the Adriatic Sea basin (Marx 2012: 100). The same E–W shift (solely for the purpose of this analysis) was selected to longitude-wise adjust the coordinates of Ptolemy’s locations identified and pinpointed on each of the three maps (Figure 5) [11]

In comparison with WGS84, Ptolemy’s coordinates showed RMSE|dLON| accuracy of 1.7° (136.8 km), and RMSE|dLAT| accuracy of 0.6° (63.9 km).[12] In comparison with Ptolemy’s dataset, the geometric centres of Ptolemy’s locations on maps, computed and plotted as point-datasets, showed RMSE| dLON| of 1.7° (135.2 km), and RMSE|dLAT| of 0.8° (86.4 km), while in comparison with the reference WGS84 coordinates, their average results are RMSE| dLON| of 1.4° (111.2 km), and RMSE|dLAT| of 0.3° (35.3 km). Both the longitudinal and latitudinal accuracy of the map coordinates proved to be higher than those of Ptolemy. Also, map coordinates proved to be more similar to the reference data than to Ptolemy’s data, which suggests that certain progress in the spatial perception of selected place-locations on the Adriatic Sea basin’s coastline had occurred during the period of map production, or slightly earlier. Geometric centres of identical points on each of the three maps show that significant longitudinal corrections have been made for the northernmost part of the Adriatic Sea, while the southernmost subset of coordinates shows significant latitudinal corrections.

Figure 5. The displacement (residual) vectors of Claudius Ptolemy’s locations for the Adriatic Sea basin in comparison: A. with their modern reference counterparts, and B: with the geometric centres of coordinates on three maps (georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from them). Each dataset is longitudinally shifted by Δλ0=−25.2°. Ptolemy’s coordinates-dataset source:Stevenson 1991. Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 5. Vektori odmaka (reziduala) Ptolemejevih lokaliteta za bazen Jadranskoga mora u usporedbi: A: s njihovim referentnim vrijednostima i B: s geometrijskim centrima koordinata na tri geografske karte (georeferencirane na vrijednosti koordinata preuzetih izravno s karata). Svaki skup podataka je longitudinalno pomaknut za Δλ0=−25,2°. Izvor Ptolemejevih koordinata:Stevenson 1991. Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

4.3 Doubly Perceived Shape of the Adriatic Sea

The coordinates of selected 45 locations on each map and chart and plotted in GIS software as point-datasets, were compared to their corresponding reference values on WGS84 (Figure 1–4,Figure 6) in order to compute their RMSE|dLON| and RMSE|dLAT| values [km]. In order to minimize their prime meridian misalignments, an individual optimal E–W shift (Δλ0) for each map and chart was computed as the average of biased displacements between the longitudes extracted from it and the longitudes of their corresponding reference points.[13] In addition, each map and chart was compared to “pseudo-coordinates” of its LSE-generated identical points,[14] which are the product of two-dimensional conformal scale-wise and orientation-wise (θLSE) adjustment of each map and chart in order to achieve their geometric best-fit according to the shape of the Adriatic Sea basin as it is rendered on them (semi-transparent coastline renderings inFigure 1–4, section B inTable 3).

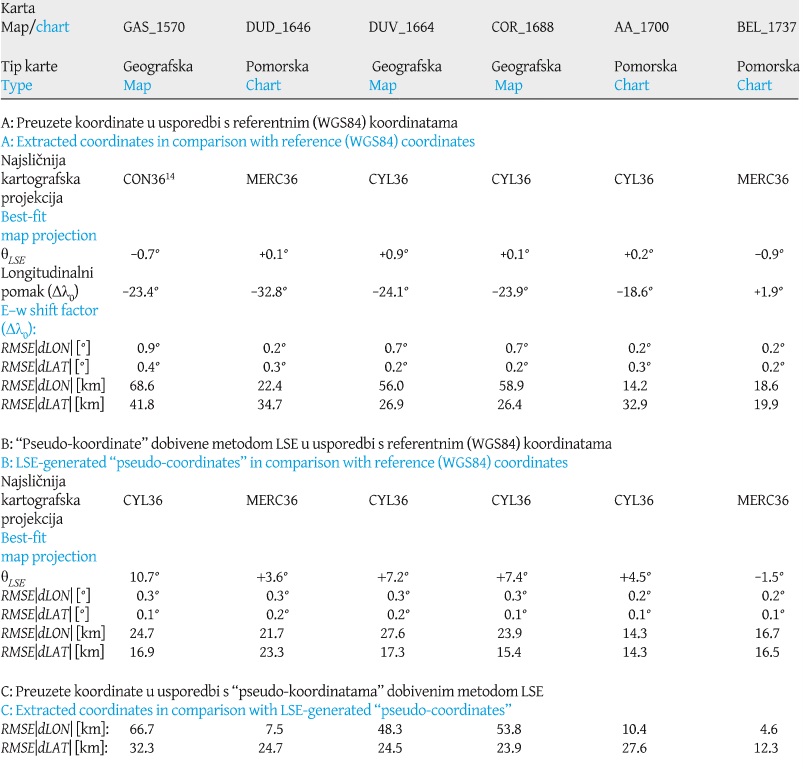

Table 3. Accuracy of coordinates extracted from charts and maps.The central meridian on Gastaldi's map is λ0=36°E. Its nearest identical point (out of 45) is Fano, so the reference projection (normal equidistant conic λ0=36°) to which its coordinates' data was compared was, thus, modified in a way that the reference longitude of Fano on WGS84 was selected as its central meridian (λ0=13,0°E, plotted as a vertical line) / Tablica 3. Točnost koordinata preuzetih s karataSrednji meridijan na Gastaldijevoj karti je λ0=36°I. Njemu najbliža identična točka (od 45) je Fano, pa je referentna projekcija (uspravna ekvidistantna konusna φ0=36°), s kojom su koordinate s karte uspoređene, modificirana tako da je referentna geografska dužina Fana na WGS84 odabrana kao srednji meridijan projekcije (λ0=13,0°I, prikazana kao vertikalna linija).

When selected maps and charts are georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from them as “pseudo-reference points”– that is, the coordinates believed-to-be-true by their authors – each one’s best-fit map projection proved to be the map projection in which they were deliberately made; normal equidistant conic φ0=36° for Gastaldi’s map (1570), normal equidistant cylindrical φ0=36° for Duval’s (1664) and Coronelli’s (1688) map, as well as for Van der Aa’s (1700) chart, and Mercator projection for the charts made by Dudley (1646) and Bellin (1737) (section A inTable 3). Van der Aa’s decision to create a nautical chart by applying a map projection that is not conformal to it (thus lacking the property of potting loxodromes as straight lines, desired in navigation) is rather unusual, but it is not the sole incidence of such practice.[15] Also, their LSE-induced rotations (θLSE) obtained from this procedure are negligible. The longitudinal accuracy of maps’ coordinates (in comparison with the reference WGS84 dataset) is significantly low – their average RMSE|dLON| is 61.1 km – while their latitudinal accuracy is relatively high, with the average RMSE|dLAT| value of 31.7 km. The latitudinal accuracy of maps is similar to the latitudinal accuracy of charts’ coordinates, which is, on average 29.2 km, unlike their longitudinal accuracy which is, somewhat to a surprise, significantly high – 18.4 km on average, thus being 60% greater than their latitudinal accuracy.

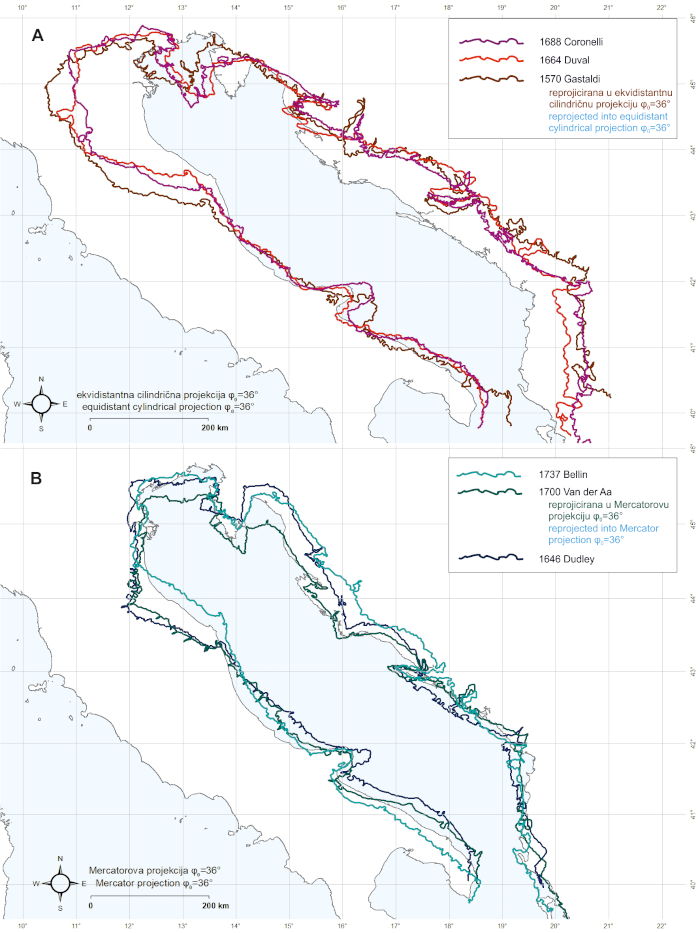

The purely geometrical approach to the georeferencing of selected maps and charts (section B inTable 3) yields somewhat intriguing results. The “pseudo-coordinates” (hypothetical, and geometry-wise ideal coordinates, derived directly from the shape of their Adriatic Sea rendering) at which the identical points on selected charts “land” after the completion of their geometric-georeferencing are longitude-wise significantly similar to their believed-to-be-true values (with a difference of only 7.5 kilometres on average). On the other hand, the comparison of coordinates extracted from maps to their “pseudo-coordinates” reveals their average longitudinal “offset” of 56.3 kilometres (section C inTable 3). Also, the LSE-induced rotations of geometrically-georeferenced maps are significant; +7.2° for Duval’s map (1664), and +7.4° for Coronelli’s (1688) map, in comparison with +0.9° and 0.1°, respectively, obtained by georeferencing them with regards to their proprietary coordinates’ dataset (“pseudo-reference points”). The accuracy of coordinates on charts (in comparison with their reference WGS84 values) proved to be very similar to the accuracy of their coordinates obtained from the geometrical best-fit of their coastlines, predominantly because of their considerably high longitudinal accuracy. This immense similarity of the results yielded from two separate and distinctively different methodological approaches explicitly demonstrates that both the perceived shape of the Adriatic Sea basin, as well as the values of coordinates assigned to selected locations are significantly more accurate[16]in comparison with the corresponding features on maps (compare thick black vectorized coastlines with semi-transparent colour-coded coastlines inFigure 1–4 and section A, and B inFigure 6).

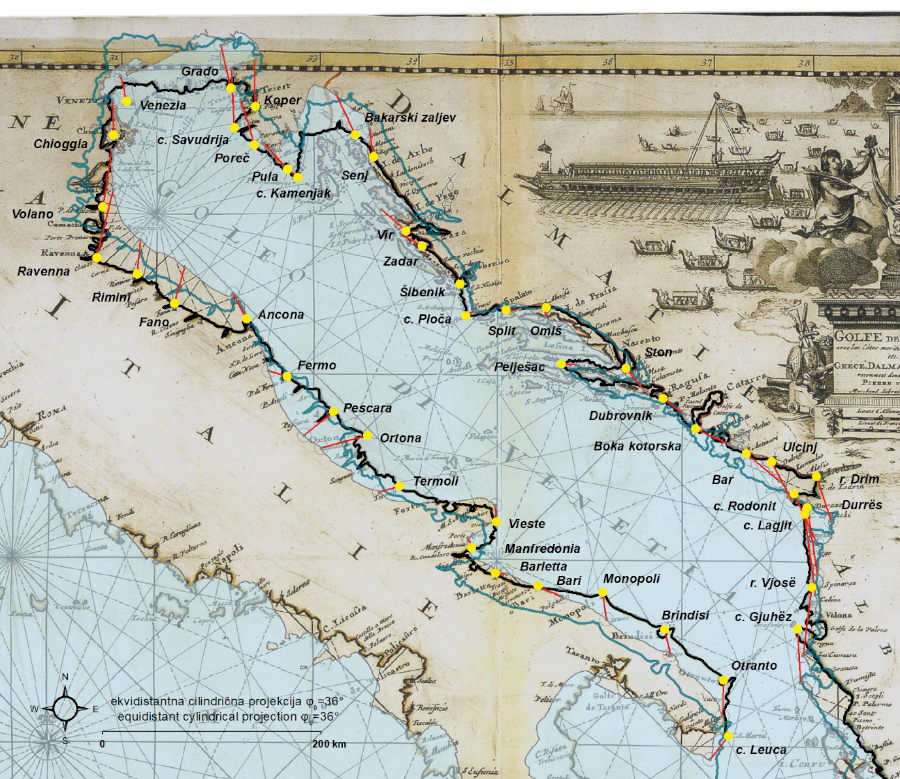

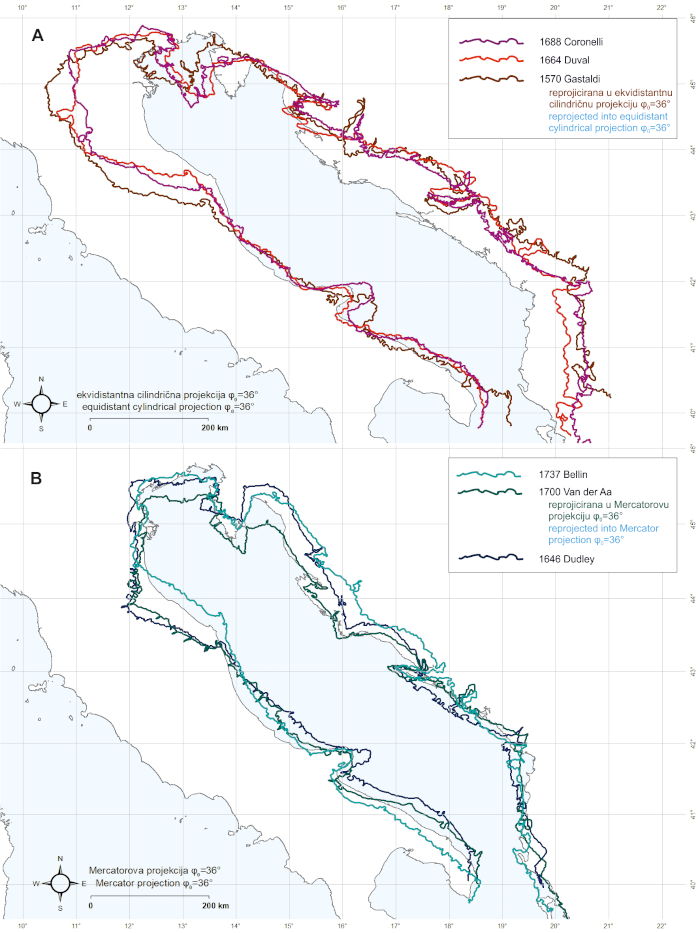

Figure 6. Vectorized coastlines of Adriatic Sea representations: A: on three maps, and B: on three charts, georeferenced by using the coordinates extracted from them, and with the application of their proprietary E – W shift (Δλ0). Basemap shapefile source: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017). / Slika 6. Vektorizirana obalna crta prikaza Jadranskog mora na: A. tri geografske karte i B. tri pomorske karte, georeferencirane na koordinate preuzete s njih uz primjenu odgovarajućeg longitudinalnog pomaka (Δλ0). Izvor pozadinskih shp datoteka: marineregions.org (Claus et al. 2017).

When the renderings of the Adriatic Sea basin’s coastline on selected maps are visually compared to its renderings on selected charts (displayed in the same map scale and aligned longitude-wise;Figure 6) it can be clearly observed that two rather different perceptions of its appearance existed in two separate “cartographic realms” in parallel. Simply put; if its actual shape, which shows rather a similar width along the majority of its geometric (NW–SE) axis, were imagined as a simplistic drawing of a (tilted) rectangle, then its shape – as it was perceived by the cartographers who created geographic maps – could be imagined as a “banana” or a “cucumber”. In a similar manner, its shape – as it was perceived by the authors of nautical charts – could be imagined as a (tilted) “funnel” (that widens towards the NW) – a “geometric footprint” which already existed on portolan charts (Marelić 2022: 95-96,2023b: 8-13).

4.4 Map Scale of Longitude-Wise Poorly Accurate Geographical Maps

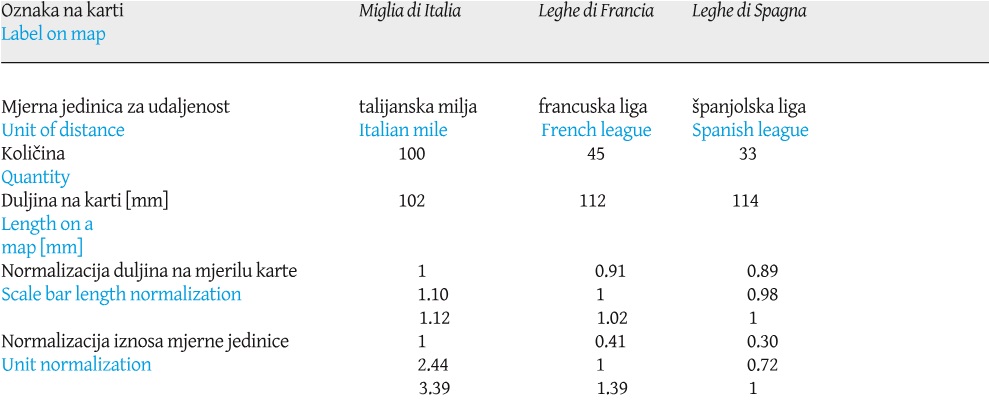

Due to significant longitudinal errors on early modern maps, it is reasonable to discuss the possible ways of computing their map scale. Some methodological possibilities will be shown in the example of Coronelli’s (1688) map, which, despite its detailed geographic content, state-of-the-art aesthetics, and six scale-bars (each calibrated in its own unit of distance), shows significant longitudinal inaccuracy (Figure 3,Figure 6) and best geometric fit with normal equidistant cylindrical projection φ0=36°, whose standard parallel is located beyond its spatial extent.

In order to compute its scale factor, the first step is to assume Coronelli’s perceived size of the Earth and the lengths of the distance units he used. Three scale bars on the COR_1688 map were considered for that matter: A: Miglia di Italia (Italian miles; 100 units, 102 mm in length), B: Leghe di Francia (French leagues; 45 units, 112 mm in length), and C: Leghe di Spagna (Spanish leagues; 33 units, 114 mm in length). Their unit-quantities ratio (100:45:33), corrected by their length-on-the-map ratio (102:112:114 mm) suggest, for example, that 1 Italian mile was (according to his map) equal to 0.41 French leagues and to 0.30 Spanish leagues (Table 4). If we assume that Coronelli used Earth’s equatorial circumference of 40,035,578.4 metres (20,541,600 toises),[17] calculated by the French astronomer and geodesist Jean Picard in 1669 (Picard 1671: 23), and that by Leghe di Francia he referred to Picard’s Lieüe de 25 au degré (25 leagues per degree) of 4,448 m (2,282 toises),[18] then the other two units should be of 1,823 m (Miglia di Italia),[19] and 6,182 m (Leghe di Spagna).[20] By the application of that criterion, 1 mm on his map scale bar corresponds to 0.17 km in reality, which yields a map scale of 1:1,787,725, or about 1:1,800,000 as its rounded value. However, neither the latitude of true scale nor his great longitudinal errors were considered to obtain this number.

Table 4. Computed interrelations between selected units of distance as represented on the scale bars of Coronelli’s map (1688). / Tablica 4. Izračunani međuodnosi između odabranih mjernih jedinica za udaljenost s obzirom na njihov prikaz na Coronellijevoj karti (1688).

If we assume that his map was believed by him to be error-free, and take into account its best geometric fit in comparison with the CYL36 projection, it means that its map scale is true along all meridians and (only) along the parallel φ=36° (which has a circumference of 32,389,463.3 m, according to Picard’s measurements, and is not displayed on the map), and that its longitudinal scale-factor errors increase with distance to the north (within the map’s extent). The mid-latitude of his map is 42°40'N (42.67°N, positioned 6.67° north of its latitude of true scale), with a circumference of 29,436,942.8 m (the perimeter of parallel φ=36° is 10% greater). This means that, if his scale bars were calibrated according to the circumference of parallel φ=36° then its longitudinal scale factor should be divided by a factor 1.10, which (for the Adriatic Sea mid-latitude) yields an “actual” longitudinal scale along its mid-parallel of 1:1,625,204[21] (1:1,625,000 as its rounded value), while its latitudinal scale remains the same.

If, additionally, we take into account his errors of the Adriatic Sea’s longitudinal extent of +2.36° (32.2% greater than its extent in reality), of which he most likely was not aware, this means that the longitudinal scale factor (which has already been divided by 1.10) should be additionally divided by 1.32, which yields an “actual” longitudinal map scale along its mid-parallel of 1:1,209,229 (1:1,210,000 as its rounded value). If we assume that Coronelli had not tailored his scale bars in accordance with φ=36° as its latitude of true scale (because it is not its mid-latitude), then its longitudinal scale factor should be divided by 1.32 exclusively, which yields a rounded longitudinal scale along its mid-parallel of 1:1,354,337 (1:1,355,000 as its rounded value). His latitudinal extent error is negligible (only 0.0012°) and was thus not considered in any of these computations. Whatever particular value should be used to describe his map scale is arbitrary; these paragraphs serve mainly to emphasize the parameters which may affect its determination and as a methodology proposal on how to determine the map scale of (poorly accurate) old maps according to these criteria. >