In the past, the European traditional sports model was established in a pyramidal structure. In German doctrine, this principle is also referred to as the Ein-Platz-Prinzip. The principle provides that in each sport, there can be only one federation per geographical level, therefore only one International Federation (IF), only one continental confederation, only one National Federation, and, as the case may be, only one regional federation.2

As such, IFs enjoy great freedom in organising themselves and their sports, which also includes establishing rules and regulations, as well as adopting them over time as they deem appropriate. This includes competition regulations of the respective sport, but also the regulations on how their sport is governed, as well as integrity policies and regulations. At the same time, the IF does however not own the sport as such, i.e. football is not owned by the International Football Federation (FIFA).

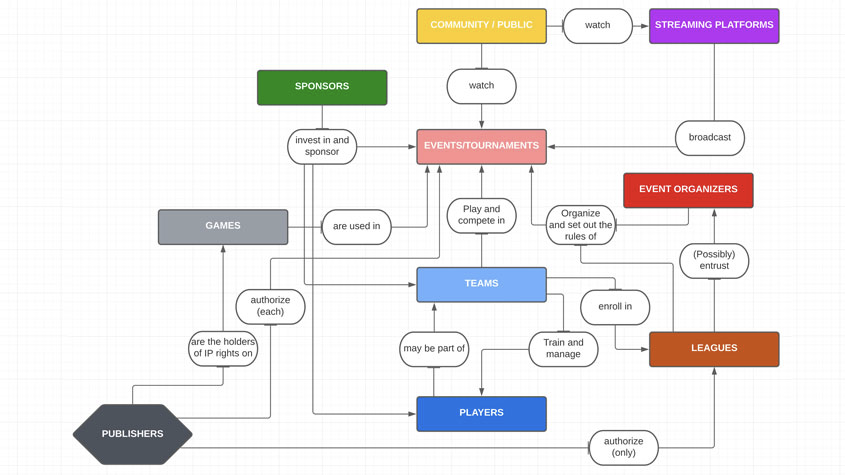

Esports, on the other hand, does not follow the same principles or structures. As described by Rizzi and de Rugeriis, and outlined in Fig. 1 below, esports represents a complex ecosystem of IP rights. This complexity is managed through a web of agreements, each of which must “converse with the others to avoid any infringement of third party IP rights.3

If one were to compare it to traditional sports, publishers would be positioned at the top of the pyramid, with the difference, however, that they fully own the games, and are free to decide who can and cannot use their rights to the games. The decision on who has the right to organise or to play in an esports competition, therefore, ultimately lays fully with the publisher. This point has to be kept in mind when it comes to integrity in esports.

Fig. 1 Complex ecosystem of IP rights. Rizzi and Rugeriis 2022, p. 4

Notwithstanding the foregoing, there are several organisations that aim to become a global or world-wide esports organisation, following somewhat the traditional sports model. For example, the Global Esports Federation (GEF) is one of them.4 In collaboration with the National Olympic Committees (NOCs), during an internal meeting in May 2023, the GEF reported the affiliation of 134 members.5 Similarly, according to information on their webpage, the International Esports Federation (IeSF) counts 130 National Federations as its members.6

In 2023, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) also launched the Olympic Esports Series (OES). The OES is a global virtual and simulated sports competition created by the IOC, and in collaboration with International Federations (IFs) and game publishers. The virtual sports included in this first series are archery, baseball, chess, cycling, dance, motor sport, sailing, shooting, tennis, and taekwondo.7 Hence, here traditional sporting organisations are extending their regulatory, development, and competition functions to also include virtual versions of their sports.

Finally, esports is trying to become recognised as sports also on a governmental level. Some examples of where esports are regarded as sports are China, South Korea, Italy, and Denmark.8

As previously seen, some merging of traditional sports and esports is currently taking place. However, some specificities in sports integrity might undermine the legitimacy, credibility, and effectiveness of such merging. The question is, thus, how do both activities compare when it comes to integrity?

The scope of this study is, therefore, to analyse integrity policies and programs in esports and draw comparisons to traditional sports where applicable.

For this purpose, the author reviewed the integrity regulations of Riot Games (EMEA) and the ESIC in May 2023. During the analysis of these regulations, the integrity threats of competition manipulation and doping were identified as the most comparable integrity issues also seen in traditional sports. Hence, this article focuses mostly on doping and match-fixing,9 while taking into account an overall view of integrity threats and programs.

More precisely, this study provides brief introductions to integrity policies and regulations, as well as integrity threats in esports. Then it delves into the coverage of persons under these regulations, offences, and sanctions, as well as disciplinary procedures relevant to Riot Games and the ESIC. Each section concludes with a comparison to traditional sports, and a discussion thereof.

As described by Czegledy , esports integrity policies are primarily adopted by two kinds of entities,10 game-neutral entities on the one hand, such as the ESIC, and game-specific entities, such as Riot Games. He suggests that when establishing integrity policies game-specific entities were to consider the protection of intellectual property proprietary technology, corporate reputation, and economic value. Whereas, the first category of entities might be expected to have policies that focus more on the actions of individuals.11

With regard to integrity threats, Czegledy proposes three broad categories of integrity issues in esports, namely (i) technological issues; (ii) player issues; and (iii) institutional issues. He then further divides technological issues as manipulation of software, such as “ aimbots,” which provide players with automatic targeting of the opponents, “wallhacks,” which allow players to manipulate properties of in-game wall and other opaque environmental elements to easily locate their opponents or other objects of interest, and “extra sensory perception” or ESP, which allows players to receive information beyond what is permitted by the developer, such as information on player health and the location and status of opponents or objects of interest.12 Other technological issues include manipulation of hardware, exploitation of in-game bugs and glitches, as well as server attacks, so-called Distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks, which occur when a network becomes maliciously flooded with traffic or information so that its intended users are unable to access it.13

Player issues include doping, match-fixing, and disabling and abusing opponents. Czegledy describes institutional issues as corruption of technicians and officials, issues with proportionality of sanctions, as well as protection of players, which seems to be lacking.14

With respect to the ESIC, prior to its establishment in July 2016,15 the current ESIC Commissioner, Ian Smith, was commissioned to carry out a threat assessment of esports, in which he identified nine (9) integrity threats, of which the four (4) most significant have been identified as, cheating to win using software cheats, online attacks to slow or disable an opponent, match-fixing, and doping.16

In traditional sports, integrity policies historically have been established by game-specific entities, with each IF implementing its integrity program in place for its respective sport. Having said that, those sports that are to be included in the Olympic Programme are required to be compliant with the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC) and the Olympic Movement Code on the Prevention of Manipulation of Competitions.17 In 2016, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) further issued safeguarding guidelines, which are to be implemented by IFs as a minimum requirement.18 In addition, integrity programs provide for codes of conduct and/or ethics codes, as well as governance and bidding regulations for certain sports.

Recently, however, an increasing number of traditional sports have decided to create at least operationally independent integrity units.19 In addition, similar to the ESIC, third-party service providers now offer integrity services on IFs’ behalf. One example is the International Testing Agency (ITA) which provides Anti-Doping services for IFs.20 In addition, there is a growing trend towards outsourcing disciplinary proceedings, which is described further in section 5.3 below.

Firstly, the author analysed which persons are covered under the respective integrity regulations. For the purpose of this study, the author analysed the regulations of Riot Games which were applied to the League of Legends (LoL) EMEA Championship for the 2023 season.

The persons covered under those regulations are the Team’s Team Managers & Team members and other employees but apply only to official League play and not to other competitions, tournaments or organised play of League of Legends.21

At the time of this research, the ESIC members included a few National Esports Federations, such as the ones of Switzerland, New Zealand, and Portugal, but mostly Tournament Operator Members, including ESL of the ESL FACEIT GROUP, organisers of the ESL Pro Tour for CS:GO, DOTA2 and STARCRAFT II tournaments.22 Pursuant to Article 1.4, the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code applies to all “Participants,” whereas the definition of participants is very broad, and includes

(i) any player who is a registered user or account holder of any Game published by or offered for play or streamed by an ESIC Member and who plays or has played or attempts to play against another Player in a Match; and/or those players serving an unexpired period of Ineligibility;

(ii) any Player Support Personnel who is employed by, represents or is otherwise affiliated to (or who has been employed by, has represented or has been otherwise affiliated to in the preceding twenty-four (24) months) a Team or Player that participates in Matches; and/or those persons serving an unexpired period of Ineligibility;

(iii) ESIC Director or ESIC Member Director, Officer, Official, Employee, Agent or Contractor engaged by ESIC or ESIC Member, Administrator, Referee or Technician.23

Participants are further bound by the ESIC Anti-Doping Code and remain bound until they have not participated or been involved in a match or event for a period of three (3) months.24

While seemingly clear on paper, in practice, jurisdiction over certain individuals can be very complex, according to the ESIC Commissioner. For example, in those cases where a participant breaches the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code while playing in a match organised by a company that is not an ESIC member but seeks to play in an ESIC-member-controlled match.25

In traditional sports, the coverage of persons under integrity regulations varies greatly. This has also been confirmed by Kuwelker et al. in their study on competition manipulation in IF’s regulations.26 At times, it concerns those participating in an event, other times it also includes officers of the IF, and sometimes it includes all athletes, support personnel and officers in the sport, including those on a national level.27 In addition, in athletics for example, the persons covered under the Integrity Code of Conduct also include Persons and entities bidding to host, or hosting, International Competitions, as well as such other persons who agree in writing to be bound by this Integrity Code of Conduct (…).28 However, pursuant to Article 2.1 of the Integrity Code of Conduct, the code shall only apply to the Area Officials and Member Federation Officials limited to their relations or dealings with the World Athletics .

The World Athletics Anti-Doping Rules also include the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) Board, employees of the AIU, and consultants and advisors of the AIU, as well as Delegated Third Parties and their employees who are involved in any aspect of doping control and/or anti-doping education.29 With regard to competition manipulations, and as confirmed by jurisprudence in this respect, clubs, i.e., not only physical persons, might also be sanctioned for these types of violations.30

In fact, many traditional sports have considered it a challenge to pursue the conducts of persons not affiliated with their sport, as the IF lacks jurisdiction over those persons. In order to bind those persons, in 2021, the International Cricket Council (ICC) introduced an Excluded Person Policy for those individuals in the ICC Anti-Corruption Code. This policy allows the ICC to conduct an investigation into the activities of any non-Participant that it reasonably believes may be a genuine threat to the integrity of the sport (for example but without limitation, where such individual is actively involved in attempting to corrupt Participants, or where he/she acts as an intermediary for someone actively involved in attempting to corrupt cricket. The ICC may issue an Exclusion Order, which will exclude the person from having any role in cricket, including financing any cricket league, tournament, event, or match, as well as from attending any match as a spectator.31

The question arises, whether an entire team in esports could be sanctioned for integrity reasons. As seen above, both Riot Games and the ESIC have jurisdiction over individuals only. The rules of Riot Games, however, allow for the exclusion of teams under eligibility requirements, which, in the author’s view, could also include integrity issues. Thus, this could end up with similar outcomes as described with regards to clubs in traditional sports. In fact, the League may, at its sole discretion, deny admission.32 Nonetheless, in the author’s view, it would be advisable to establish clear rules in this regard. In contrast, specific rules do exist for team exclusion when it comes to poaching of players, a threat outlined further in section 4.1 below.

4.1. RIOT GAMES

In the following section, the author explores the sanctions available under different integrity programs. Starting with Riot Games, the regulations specify the following categories of sanctions:

Verbal Warning

Loss of Side Selection for current or future Game(s)

Loss of Ban(s) for Current or Future Game(s)

Fine(s) and/or Prize Forfeiture(s)

Game and/or Match Forfeiture(s)

Suspension(s)

Disqualification(s)

More specifically, Riot Games provides a LEC Penalty Index and/or the Global Penalty Index for major infractions according to its rules.33 When looking at the LoL Esports Global Penalty Index,34 Ongoing Misconduct, which is defined as major repeated instances of unacceptable behaviour towards another person or persons, and Extreme Misconduct, which is defined as a single instance of extraordinarily inappropriate behaviour, are punished with a suspension of three (3) to ten (10) competitive months. The statute of limitation for these offences is one (1) year.35

Riot Games imposes so-called life bans which are foreseen for match-fixing and cheating in professional play offences. Riot Games defines match-fixing as influencing or attempting to perversely influence the outcome of a match, and cheating in professional play as, the utilization of any illicit in or out-of-game technique to affect competitive play in a majorly impactful way,36 such as electronic signaling, hacks, etc. The minimum suspension foreseen for those offences is ten (10) competitive months, which effectively translates to a one (1) year suspension, as all months but November and December are considered competitive months. The maximum suspension is indefinite, and the statute of limitations for these offences is three (3) years.

Whereas, when it comes to colluding with other teams or individuals to manipulate ranked rating for the purpose of entering a sanctioned qualifier, the sanction range is five (5) to ten (10) competitive months, with a statute of limitation of one (1) year. Finally, wagering on semi-professional or professional games, carries the same sanctions as the production, usage, distribution of non-compliant programs such as hacks, exploits in public play,37 namely ten (10) to twenty (20) competitive months. The statute of limitation for these offences is also one (1) year.

According to the sanctions recorded by Riot Games for the EMEA region at the time of research, five (5) individuals have been suspended for life, of which three (3) for match-fixing and collusion, one (1) for extreme toxicity, and the remaining for toxic behaviour & harassment.38

Another esports specific category of sanctions concerns the poaching of players while under contract by another team. In this regard, three offences are outlined on the LoL Esports Global Penalty Index, namely firstly, concerning a player intensively tampering with or poaching another player,39 secondly, a non-player team affiliate intensively tampering or poaching a player,40 and thirdly a player or coach enticing or soliciting teams to poach player or coach.41 For the first and third offence the suspension ranges are from five (5) and three (3) to ten (10) competitive months respectively. The sanction for the second offence is a minimum ten (10) competitive month suspension, in addition to acquisition being blocked, and a large organizational fine at the League’s discretion. Furthermore, the League may deny entry or presence into Riot-sanctioned leagues in any official capacity. The suspension range goes all the way to an indefinite suspension.

Extenuating or aggravating circumstances may qualify for a reduction or increase in the length of suspensions. However, those actions that have already been penalized and occurred more than 1 calendar year in the past will not be considered aggravating.42

At the time of this research, Riot Games seems not to have introduced any specific anti-doping regulations. The LoL rules in Article 12.2.8 provide that A Team Member/Member may not engage in any activity which is prohibited by common law, statute, or treaty and which leads to or may be reasonably deemed likely to lead to conviction in any court or competent jurisdiction. This includes but is not limited to the use of substances prohibited by law in Germany any other potentially applicable jurisdiction. In Germany, the Anti-Doping Act came into force on 10 December 2015, thus, doping has been considered a criminal offence since then.43 However, whether the Anti-Doping Act applies to esports seems unclear,44 and it has been discussed as being negative since esports would not fall within the definition of “sports” under the Anti-Doping Act. That said, narcotics laws still apply, which do however not prohibit the presence of narcotics, but criminalise only the possession and distribution of those substances.45

4.2. THE ESIC

The ESIC rules provide for a code of ethics, a code of conduct, an anti-corruption code, and an anti-doping code. While the code of ethics governs the conduct of persons serving on the executive board of ESIC,46 the other codes apply to the Participants.

Depending on the gravity of the conduct, offences under the code of conduct are divided into four (4) levels. The severity of the sanctions imposed corresponds to the level of the offence with higher-level offences, receiving more severe sanctions. The sanction will also be increased for repeat offenders within a period of twenty-four (24) months, as outlined in Fig. 2 below. The same period of time will be taken into consideration for the accumulation of suspension points. Any fines are directly deducted from the prize money due to the player and redistributed amongst all other players/teams eligible for prize money in the relevant match or event.47

Swearing is for example considered a Level 1 offence, whereas, Level 2 offences include the deliberate and malicious distraction or obstruction of another Participant during a Match, but also Any attempt to manipulate a Match for inappropriate strategic or tactical reasons, such as when a player or a team deliberately loses a pool match in an event in order to affect the standings of other players or teams in that event. Intimidation of any participant and a threat of assault on another participant or any other person are considered Level 3 infractions, while physical assault and acts of violence are considered Level 4 offences. Depending on the nature and seriousness of the cheating or attempting to cheat to win a Game or Match, the conduct is categorised as either a Level 3 or a Level 4 offence. Examples of these types of cheating include map hacks, aimbots, ghosting, or any external software that directly tampers with the game software to gain an advantage in the game.48

Fig. 2 Sanctions according to Article 7 of the ESIC Code of Conduct

The ESIC Anti-Corruption Code, on the other hand, foresees four (4) categories of sanctions, namely Corruption, Betting, Misuse of Inside Information, and others.49 Under ESIC rules the term corruption is defined as:

2.1.1 Fixing or contriving in any way or otherwise influencing improperly, or being a party to any agreement or effort to fix or contrive in any way or otherwise influence improperly, the result, progress, conduct or any other aspect of any Match, including (without limitation) by deliberately underperforming therein.

2.1.2 Ensuring for Betting or other corrupt purposes the occurrence of a particular incident in a Match or Event. (…)

2.1.3 Seeking, accepting, offering or agreeing to accept any bribe or other Reward to: (a) fix or to contrive in any way or otherwise to influence improperly the result, progress, conduct or any other aspect of any Match; or (b) ensure for Betting or other corrupt purposes the occurrence of a particular incident in a Match.

2.1.4 Directly or indirectly soliciting, inducing, enticing, instructing, persuading, encouraging or intentionally facilitating any Participant to breach any of the foregoing provisions of this Article 2.1.50

Individuals will be sanctioned with a period of ineligibility ranging from two (2) events to a lifetime. Betting, on the other hand, carries a period of ineligibility from two (2) events to two (2) years, while the misuse of inside information range of sanctions spans from no minimum period of ineligibility to three (3) years.51

The fourth category of offences includes giving or providing gifts, payments, hospitality, or other benefits to procure, directly or indirectly, any breach of the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code, failing to disclose to ESIC the receipt of any such gifts, payments, hospitality, or other benefits, as well as failing to disclose in general any gifts, hospitality, or benefits that have a value of USD 500 or more.

In addition, participants have the obligation to report to ESIC any approaches or invitations received by the Participant to engage in Corrupt Conduct under the Anti-Corruption Code, as well as to disclose full details of any incident, fact, or matter that comes to the attention of a Participant that may evidence Corrupt Conduct under the Anti-Corruption Code by another Participant (…). Failing to report such approaches and incidents is considered an offence,52 which is punishable with a period of ineligibility from two (2) events to five (5) years.

Interestingly, the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code requires individuals to undergo education sessions and additional reasonable and proportionate monitoring procedures prior to becoming re-eligible.53 Rehabilitation programs, education, and social work have also been included by some IFs in their rules as measures for competition manipulations.54 Similarly, in anti-doping, rehabilitation measures are foreseen for so-called Substances of Abuse, a category introduced with the 2021 WADC. If an Athlete undergoes a Substance of Abuse treatment program, the sanction for those substances may be reduced to one (1) month, provided that the use of those substances occurred out-of-competition and was unrelated to sport performance.55

While the use of doping in esports seems to be widely confirmed, the performance-enhancing effects are still discussed, with further scientific studies wanted.56 Esports are generally compared with mind sports, like chess and poker, when it comes to performance-enhancing substances. In these sports, stimulants that increase attention and suppress fatigue and tiredness are seen as the most helpful category of substances for enhancing performance.57 Esports players themselves have admitted to playing better when taking Adderall, for example.58 Even leaving the potential for performance enhancement aside, if one were to apply the three criteria for which substances are put on the WADA Prohibited List, the remaining two, i.e., health risk and violation of the spirit of the sport would certainly be fulfilled.59

Contrary to the extensive WADA Prohibited List, the ESIC Esports Prohibited List is limited to the following substances (examples of brand names):60

Amphetamine sulfate (Evekeo)

Dextroamphetamine (Adderall and Adderall XR),

Dexedrine, (ProCentra, Zenzedi)

Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin and Focalin XR)

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse)

Methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD and Metadate ER, Methylin and Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin SR, Ritalin LA, Quillivant XR)

Modafinil and armodafinil.

While generally following the principles of the WADC, there are a few major distinctions in the ESIC Anti-Doping Code. Firstly, under the ESIC Anti-Doping Code, Prohibited Association is not considered a violation per se, but only adverse inference may be drawn by the panel deciding the case. Therefore, the rules suggest avoiding any association with persons who are banned by ESIC for a doping offence or any other Anti-Doping Organisation, or who appear on the WADA warning list.61 The ESIC Anti-Doping Code does not include the newly added violation of “Retaliation,” which was included in the 2021 WADC.62

Furthermore, pursuant to Article 6.6 of the ESIC Anti-Doping Code, the Integrity Commissioner may recommend that a player undergoes at his own expense a programme of assessment, counselling, treatment, or rehabilitation, without referring the case to discipline, where it concerns a case of recreational drugs.

Finally, the range of sanctions is the same as for a Level 4 offence in the code of conduct, i.e., technological cheating. For a first offence a fine of up to 100% of a Match and/or Event Prize money (or equivalent) and/or between four (4) and eight (8) Suspension Points and/or a fixed term of suspension from the Game and/or Event/s of up to twenty (24) months is foreseen, while a second offence carries a period of ineligibility between 1 year and a lifetime, and a third offence up to a lifetime suspension from all esports.63 When determining the sanction, the Integrity Commissioner or Panel will take into account any other factors that they deem relevant and appropriate for mitigating or aggravating the nature of the Anti-Doping Policy offence.64

While aggravating and mitigating factors do play a role in traditional sports that implement anti-doping rules in compliance with the WADC, the primary factors determining the sanction are the type of Prohibited Substance, i.e., whether it concerns a Specified or non-Specified Prohibited Substance, Intent, as well as the degree of Fault or Negligence.65

For example, Adderall contains Amfetamine and Dexamfetamine, which are listed under Stimulants in S6.A on the WADA Prohibited List and considered Non-Specified Substances, prohibited In-Competition only. This means that under the WADC, the starting sanction is four (4) years. If the Athlete can show that the violation was not intentional, the maximum sanction is up to two (2) years. If the Athlete can also establish No Fault or Negligence, which only applies in exceptional circumstances, then no period of ineligibility would apply. If the Athlete can establish No Significant Fault or Negligence a period of Ineligibility between one (1) and two (2) years applies. Only in cases of Contaminated Products can a reprimand be issued, with no period of Ineligibility or a maximum period of up to two (2) years.66 Technically speaking, the maximum period of ineligibility is, therefore, double the length under the WADC in comparison to the ESIC sanctions, i.e., two (2) versus four (4) years of Ineligibility.

4.3. TRADITIONAL SPORTS AND DISCUSSION

In traditional sports, one of the main purposes of the WADC is to ensure harmonisation in anti-doping, including the uniformity of violations and sanctions.67 The IOC’s aim in issuing the 2018 Guidelines for Sports Organisations on the Sanctioning of Competition Manipulation (IOC Sanctioning Guidelines)68 was the same, i.e., to achieve some degree of harmonisation in the sanctions applied to competition manipulation.

For example, according to the IOC Sanctioning Guidelines, offences related to manipulation of sports competitions and corrupt conduct recommend sanctions of approximately a four (4) year ban and a fine for betting-related conduct, and approximately a two (2) year ban and a fine for sport-related conduct, subject to mitigating and aggravating circumstances .69 However, according to research by Kuwelker et al., most competition manipulation related decisions at the IF level for those sports where match-fixing is ripe, i.e. football, tennis, cricket, and badminton, have seen life bans or at least career-ending bans.70

As previously described, the sanctions for match-fixing according to the LoL Global Esports Penalty Index range from ten (10) competitive months to indefinite, while the same conduct under the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code provides for a period of ineligibility from two (2) events to lifetime.

As seen, sports-related manipulation71 in traditional sports carries a ban of two (2) years. The offense of “tactical loss” has also been included in the Council of Europe’s Convention on the Manipulation of Sport Competitions (Macolin Convention), and as such, has been included as a criminal offence in countries that have ratified the convention, such as Switzerland for example. Whether a tactical loss should be considered a crime is widely discussed and has been openly criticised by scholars. It has been suggested that such behaviour should rather be sanctioned by the relevant sporting regulations or preferably, lead to a change of the rules of the game and/or conduct of a competition.72

Both, ESIC and Riot Games, clearly distinguish match-fixing from tactical losses. ESIC includes the latter as a Level 2 offence in its code of conduct rather than in the anti-corruption code. A Level 2 offence involves any attempt to manipulate a Match for inappropriate strategic or tactical reasons. To recall, a first offence is punishable with only a fine of up to 50% of a Match and/or Event prize money (or equivalent) and/or up to two (2) Suspension Points. Riot Games has a similar offence called Ranked Ladder Manipulation for Qualifiers , a stand-alone offence from match-fixing, which is sanctioned with a suspension of 5 to 10 competitive months.

Like many anti-corruption codes in traditional sports,73 participants have a reporting obligation under Article 2 of the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code. Failure to report constitutes an offence. While ESIC includes any approaches or invitations received by a participant or known to a participant concerning another participant, the anti-corruption code in tennis goes even further and explicitly prohibits those covered by the code from dissuading or preventing any other covered person from complying with any reporting obligation,74 i.e., similar to the Retaliation offence in anti-doping. The respective regulations analysed by Riot Games are silent on any reporting obligations and do not appear to sanction any such conduct.

As outlined in section 4.2 above, failure to report is sanctioned with a suspension ranging from two (2) events to a maximum of up to five (5) years. In traditional sport, according to an analysis by Haas and Hessert, the basic sanction deriving from CAS jurisprudence and international association tribunals for failure to report ranges from six (6) to twelve (12) months.75 The IOC Sanctioning Guidelines recommend a ban ranging from 0 to two (2) years and a fine.76

Failure to cooperate has to be distinguished from a failure to report. The purpose of the duty to cooperate is ultimately for the sports organisation to determine whether a match manipulation has occurred, and thus facilitate investigations by sports organisations.77 In this respect, the IOC Sanctioning Guidelines distinguish between a failure to provide requested assistance, where the same sanction as for a failure to report is recommended, while obstructing or delaying investigation should be punished with a ban from 1-2 years and a fine.

Regarding cooperation duties, disciplinary proceedings from sports organisations have to be distinguished from potential criminal proceedings that may be initiated for the same conduct depending on national laws with regard to match-fixing and doping. Sports organisations and law enforcement agencies might share intelligence or investigation results with each other. Hessert argues that the forced nature of the disclosure of all kind of information, including self-incriminating information, plays a significant role in answering the question whether the exchange of information between sports organisations and law enforcement agencies is compatible with the defence rights of athletes in criminal proceedings. He suggests that the best solution is to permit the forced provision of information for the purpose of finding the truth in internal sport investigations. Simultaneously, sports organisations should adhere to the principle of nemo tenetur se ipseum accusare, refraining from sharing self-incriminating information with law enforcement agencies.78

The other end of the scale seems to be athletes, support personnel, and at times also sport administrators, who are trying to conceal conduct, such as doping. The AIU has, for example, prosecuted several cases where medical documents were forged, dates on emails altered, fake doctors, hospital appointments, and treatments put forward.79 In fact, tampering or attempted tampering with any part of the doping control by an athlete or other person, which includes tampering during the results management process, is considered a separate anti-doping rule violation under the WADC.80 This might lead to athletes being suspended for eight (8) years or even longer, instead of four (4) years, i.e., for the presence of a prohibited substance and for tampering.

5.1. RIOT GAMES

Riot Games rules provide for a review procedure upon the League’s determination of a Major Rules Violation, i.e., in a first instance the League decides of any violation and sanctions thereof. The review procedure is either Expedited, i.e., completed within 24 hours, or Non-Expedited. It is the League that will form a committee consisting of three non-case related Rioters. For Non-Expedited review, the League forms a committee comprising a representative from the affected team, a league representative, and an agreed-upon third party. Reviews are not de novo, and no new evidence is allowed during this procedure.81

5.2. THE ESIC

The ESIC, on the other hand, has established specific regulations for disciplinary procedures, providing for either a Simple Procedure or a Full Procedure.82 The Simple Procedure applies to alleged Level 1 or Level 2 code of conduct offences in which the Integrity Commissioner makes decisions regarding whether a violation occurred and the extent of the sanction. The aim of the Simple Procedure seems to be to deal with the matters within a short time frame. In fact, the rules foresee that a hearing (if any) is to be held within thirty-six (36) hours of the Notice of Charge, and a decision is to be issued by the Integrity Commissioner no later than forty-eight (48) hours from the conclusion of the hearing. Decisions for Level 1 offences are not appealable.

The Full Procedure applies to alleged Level 3 and Level 4 offences under the ESIC Code of Conduct, alleged breaches of the ESIC Anti-Corruption Code, and alleged violations under the ESIC Anti-Doping Policy. The chairman of the ESIC Panel (its appointment is outlined further below) appoints one member to sit as the adjudicator to hear the case concerning an alleged Code of Conduct violation. For serious Code of Conduct cases, as well as for alleged violations of the Anti-Corruption Code or Anti-Doping Code, a three-member panel hears the case. Similar to the Simple Procedure, the adjudicator is to issue a decision within forty-eight (48) hours from the conclusion of the hearing, and the hearing should take place no longer than fourteen (14) days from the receipt of the Notice of Charge. Except for a first Level 1 offence under the Code of Conduct, all decisions are appealable to an Appeal Panel, which decides matters on a de novo basis. The procedural time limits are as follows. The Notice of Appeal must be lodged with the Integrity Commissioner within forty-eight (48) hours of receiving the decision. Within forty-eight (48) hours of receiving the Notice to Appeal an Appeal Panel is to be appointed. An appeal hearing shall commence no later than seven (7) days from the appointment of the Appeal Panel. Any decisions made by the Appeal Panel are final and binding.

As the ESIC Disciplinary Procedure describes in its introductory section, the ESIC Panel is made up of legally experienced, independent individuals from various jurisdictions. Where a three-member panel is to be appointed the chairman of the panel shall be appointed by the chairman of the ESIC Panel, one member shall be nominated by the accused party, and the remaining member shall be nominated by the Integrity Commissioner.83

5.3. TRADITIONAL SPORTS AND DISCUSSION

In traditional sports, IFs establish bodies or organs, so-called association tribunals, which are competent to make certain decisions, including regulatory decisions, disciplinary decisions, etc.84 Depending on the IF, there may be either a single level only, or the possibility to appeal decisions internally within the IF, similar to the case of ESIC’s Appeal Panel.

The lack of harmonisation in dispute resolution mechanisms within IFs has also been confirmed by Kuwelker et al. with regard to match-fixing. They found that some IFs, such as the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), have procedures unique to manipulation offences. Others have a combination of specific regulations and certain provisions that apply to uniform procedures or sanctions, or make specific exemptions. The rest, such as tennis under the TACP, have uniform processes for all disciplinary and/or other disputes within the federation.85

Final decisions of association tribunals may be appealable to arbitration tribunals, such as the Court of Arbitration (CAS), or to ordinary courts. Pursuant to R47 of the Code of Sports-related Arbitration (CAS Code), the requirement for such an appeal is, in addition to an arbitration clause in the statutes or regulations of the IFs or a specific arbitration agreement, the legal remedies available within the federations’ internal dispute resolution mechanisms must have been exhausted.86

In equestrian, for example, minor cases may be administratively processed via a so‑called Administrative Disciplinary Procedure, where the sanctions include, but are not limited to, a warning, a fine not exceeding 2,000 Swiss Francs, or a suspension of up to three-months. This includes breaches of the FEI Code on the Manipulation of Competitions for which sanctions from a warning to life might be imposed, as well as a fine from 1,000 to 15,000 Swiss Francs.87 One can expect that the aim of simplified procedures, such as the one used by the FEI, as well as Riot Games’ Expedited Procedure, and the Simple Procedure under the ESIC rules, is to deal with minor cases in a time- and resource-efficient way. However, it has to be noted that in all three aforementioned cases, the prosecutor also becomes at the same time the decision-taker, which has to be questioned by itself. That said, in the FEI case, parties can request that cases be dealt with by the independent FEI Tribunal, whereas this possibility does not exist for Riot Games or for the ESIC. Neither Riot Games nor ESIC provide the possibility to appeal internal decisions to an arbitration tribunal. It is to be expected that the parties to the dispute refer their cases to ordinary courts in the respective countries.

Concerning anti-doping, the latest edition of the WADC requires anti-doping hearing panels to be ‘operationally independent.’ The accompanying WADC guidelines also clarify that, apart from not being involved in any other capacity within an IF, an anti-doping hearing panel member cannot have any part in the investigation or pre-adjudication of the matter. In response to this requirement, some IFs, such as the International Tennis Federation (ITF), have chosen to refer their anti-doping cases to the Independent Hearing Panel of Sport Resolutions UK, which determines first-instance anti-doping matters for IFs or other Anti-Doping Organisations wishing to make use of the tribunal’s services. Other IFs refer their anti-doping matters to the CAS Anti-Doping Division (ADD).88

The ESIC would clearly not fulfil this operational independence requirement when it comes to recreational drugs, as these fall within the arbitrary decision of the Commissioner, who may choose not to refer them to discipline. Returning to equestrian and regulations for Controlled Medication Substances applicable to equines, an Administrative Procedure exists where certain circumstances are fulfilled. These include cases where only one (1) Controlled Medication Substance is detected in the Sample, first-time offenders, considered as those not having had any cases within the past four (4) years, and the event in question is not a major event, such as the Olympic Games. Also here, the person charged may elect to have the case heard by the FEI Tribunal.89

This study has aimed to analyse and describe integrity policies and programs in esports, drawing comparisons to similar policies and programs in place in traditional sports. The integrity threats of competition manipulation and doping were found to be comparable to the policies and programs put in place in traditional sports.

However, as described in this article, in addition to match-fixing and doping, additional threats have been considered significant for esports, namely the use of software cheats, the manipulation of hardware, the exploitation of in-game bugs and glitches, or server attacks. These threats, often referred to as e-doping, or technological issues outlined in this article, are particular to esports and do not necessarily exist in traditional sports. This means that integrity policies and programs in esports need to take into consideration also these threats, thus encompassing a wider range of threats compared to traditional sports.

Throughout the study, it has become clear that ESIC is somewhat adopting elements from traditional sports integrity programs, albeit with some major differences, and seems to have tailored the traditional policies to suit the requirements of esports. Riot Games, on the other hand, differentiates quite a lot from traditional integrity policies. At the time of the study, regulations and procedures were not as developed as in traditional sports or as found with the ESIC. However, as the publisher and the esports game organiser, licenses could simply be revoked at any time for any reason, including integrity reasons.

In the author's view, integrity programs in esports are only partially comparable to the ones in traditional sports, particularly regarding some individual threats, such as competition manipulation and doping. One still needs to take into account specificities in esports with regard to these threats. For example, skin gambling, which does not exist in traditional sports, or the type of substances used on the one hand, and their potential to enhance an esports player’s performance on the other hand.

Most importantly, esports integrity programs need to – in addition - also focus on the e-doping threat which is specific to esports. Those traditional sports that wish to include virtual competitions into their activities, should be aware of these additional threats, assess the risks, and establish strategies to prevent and encounter these threats. Thus, for example, cycling competitions and virtual cycling competitions cannot be considered the same sport from an integrity standpoint.

The establishment of integrity programs in esports is quite recent, suggesting that we can expect further evolution in the upcoming years. This article has reviewed only some of the regulations and integrity programs in place in esports. Further studies of the remaining players in the esports industries would provide a more complete picture of the existing or non-existing esports integrity programs. In addition, a study of the evolution of such integrity programs over time, as well as of their effectiveness would provide further insights into this topic.