1. INTRODUCTION

Scientists agree that entrepreneurship plays an important role in the economic development through innovation and job creation. The relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment is analyzed through two -way communication, i.e. the unemployment push effect (necessity-based entrepreneurship) and the prosperity pull effect (opportunity-based entrepreneurship) (Parker et al., 2004). According to the unemployment push effect, high unemployment reduces the chances to obtain a stable job, and an expected income from employment, so the unemployed person is ‘’pushed’’ or forced to start a small business. However, according toRemeikienee and Startiene (2009), if the country has a high unemployment rate, entrepreneurs face reduced demand for their products or services. The high unemployment rate weakens the consumers’ buying power which leads to increasing the risk of bankruptcy and entrepreneurs and be easily pulled out of the private sector. According to the prosperity pull, individuals will open a business if the country’s economic situation will allow thus reducing the unemployment rate (Remeikiene & Startiene, 2009). According to Muhelberger, (2007) inRemeikiene and Startiene (2009), individuals tend to be self-employed when unemployment is low, since the chances of returning to a wage labor are higher.

2. THE RELATIONSHIP OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT

After the financial crises in 2008, Europe had for the first time more than 23 million unemployed, and majority of small and medium enterprises had not been able to jump back to the previous levels of employment (Rotar, 2014). According to data by Eurostat the youth unemployment rate was 23.9% (EU28) in the first quarter of 2013, and declined to 19.7% at the end of 2015. According to the International Labor Organization, the global youth unemployment rate was 16.6% in 2013, and in the EU youth unemployment increased by as much as 24.9% between 2008 and 2012 (Gopalakrishnan, 2016). Since the unemployment issue had appeared in Europe, EU member states have been using different tools to fight it. One of the tools that Europe has been using is entrepreneurship.Rotar (2014) agrees that entrepreneurship plays an important role to tackle the unemployment, especially the youth unemployment. Unemployment in the Western Balkans on the other side has been a key macroeconomic problem during the process of transition. It is four to five times higher in this part of Europe compared to other European Union Countries. However, studies show that youth unemployment is a worrying fact in both less developed and developed countries (Stevanovic and Bogdanovic, 2018). Signorelli (2017) states that unlike planned economies, transition economies have higher and unstable unemployment rates especially youth unemployment.

The integration of young individuals in the labor market is not a smooth process. Young people face a lack or a mismatch of skills and experience when entering the labor market. In the US there are 11 million unemployed people, and 4 million unfilled jobs, as a result of skills mismatch (Gopalakrishnan, 2016). Because of lack of experience, getting a job for many young people can be a great issue, which can bring long-term unemployment among youth. This long-term unemployment influences in general happiness, and social dissatisfaction among the youth, and can also have long-term scars on the working adults of the next generation (OECD, 2001). Scientists agree that young people should have entrepreneurial education to prepare them for entering the labor market. Entrepreneurial education should spread an entrepreneurial culture among students and staff, foster innovation and innovative thinking and should find ways to encourage exchange and knowledge transfer between the university, industry, and the local communities (Sandri, 2016). But, in order to promote entrepreneurial activity among young people, it is crucial to learn more about young people’s awareness and attitudes and aspirations towards entrepreneurship and business (Schoof, 2006).

According to a Euro barometer survey cited inRotar (2014), the number of young people interested in self-employed business surpasses the number of middle aged people. It was found that middle age people generally do not want to take risks, they want to have stability in their job, and they are happier to have a regular fixed income versus an irregular variable income. On the other hand, young people are more interested in becoming self-employed because of personal independence, the desire to seek out new challenges, to earn more money, to realize an idea or vision, to gain more reputation, and to connect a passion with a job (Schoof, 2006). However,Barringer et al. (2011), states that the total number of young entrepreneurs is lower than women entrepreneurs, minority or senior entrepreneurs, but their interest in entrepreneurship is growing. According toRotar (2014), Slovenian young people are very interested in start-up businesses because they think about what they can do for themselves instead of what the government can do for them, and with some changes in labor market policy, the number of young entrepreneurs can increase in Slovenia. Youth in Serbia also shows interest in entrepreneurship, with significant differences in interest among people who know entrepreneurs and those who do not know. Studies in Serbia prove the statement above regarding women participation in entrepreneurship and that men are more interested in becoming entrepreneurs than women (Stevanovic and Bogdanovic, 2018).

The structure of early stage entrepreneurship by age is similar across regions. Most entrepreneurs fall into the age group of 25 to 34 and from 35 to 44 years. It is important to note some differences observed in different regions. Thus, young entrepreneurs in the early stage of the group 18-24 years are most commonly seen in the European Union and North America, and the group of older entrepreneurs 55-64 years in the sub-Saharan Africa region. However, according to the GEM Report (2016/17), the low participation of youth entrepreneurs can be affected by tertiary education, compulsory military service in some countries or the access to finance since young people often do not have credit history or assets to serve as collateral for obtaining a loan. For example, in North Macedonia experts agree mostly with the following statements: “Most young people who have become entrepreneurs have been helped to start up by their families, close relatives or friends”.; and “Young people find life / work opportunities abroad more attractive”. They also consider that “financiers (banks, informal investors, business angels...)” are less likely to finance business initiatives from young people, compared to all other countries (GEM, 2013).

Transition Economies, Unemployment and Entrepreneurship

During the nineties the Eastern Europe and former Soviet Union countries, started to move from a centrally planned communist economy to a free market economy. In terms of implementation, the transition did not occur in all countries at the same time. Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary were the first countries in Central and Eastern Europe that launched plans for privatization, with Hungary having started testing market-oriented reforms since the 1980s (Blokker et al., 2008). This transition brought many political, economical and social issues to the countries. One of the main issues that all these countries have struggled in the beginning of the transition has been the decrease of GDP, which took all transition countries in recession in 1991. On the other side the bad economic performance brought problems in the performance of the labor market (Bah et al., 2014). As a result of the sharp decline in the economic performance in the transition countries, employment started to decline and the demand for labor collapsed immediately (Nestorova, 2002), which mostly were affected the youth population. On the long – run, the political and economical instability characterized the transition economies with slow economic growth and high unemployment rate (Bah et al., 2014).

According to GEM model, most of transition countries are in efficiency-driven economy. With the fall of communism in 1989, the development of small businesses became one of the main reform goals of the post-communist governments. The new governments reacted by quickly removing the main barriers to entry, and privatizing the small business sector and by taking over the basic reforms in the financial sector. As a result of these new opportunities, almost everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe a race for registration of new small businesses appeared. The support of international organizations such as: World Bank, UNDP, PHARE. USAID etc played a significant role in encouraging small businesses in transition countries (Fiti et al., 2007). According to Estrin and Mickiewicz (2010), in transition economies the rate of entrepreneurship is lower than in developed and developing market economies, and this low rate is more expressed in the countries of former Soviet Union than those of Central and Eastern Europe. The low rate of entrepreneurship is presumed to be as a result of slow adaptation of informal institutions, social norms and attitudes.

The economy in MENA region is a heterogeneous macroeconomic context dependent on the oil industry. Most of the GDP is based on oil and government activities related with the oil industry (Tagliapietra, 2017). This region has the highest rates of youth population in the world, but also the highest rates of youth unemployment (Kabbani, 2019). Almost every second young educated person in this region is unemployed (OECD, 2016). The top priority of this region has been job generation, since this region suffers from long-term unemployment (O’Sullivan, n/a). On of the tools to tackle the unemployment has been entrepreneurship, since data show that entrepreneurship in this region has a large opporotunity for development, since it is one of the most digitalized regions in the world, with 88% of the population being online daily (Alkasmi, 2018). On the other hand data show that entrepreneurship on the other hand highly present in the MENA region, even higher than USA and Germany, but most the entrepreneurships are necessitybased such as shop owners or cart sellers and farmers who try to satisfy their basic needs (World Economic Forum, 2011).

From the literature review, we can conclude that youth labor is important for the economy. Even though they lack skills and experience they bring enthusiasm and ideas to the labor market. Many of them want to accomplish their entrepreneurial ideas by starting a business; however they face difficulties with financial support. We can also conclude that young people are the most vulnerable group in the labor market in both transition and MENA countries.

3. METHODOLOGY

To accomplish the research objective, an econometric analysis of secondary data was conducted in Stata 12, to present the relationship of entrepreneurship and youth unemployment. The dependent variable i.e. youth unemployment data were collected from the World Development Indicators database, and represent young people from the age 15 to 25 without work but available for and seeking a job from the total youth labor force. On the other hand measuring entrepreneurship on either individual level or on an aggregated level arises many difficulties. It is simply not possible to collect individual characteristics within a data set that can be comparable over nations. Therefore, the measurements of entrepreneurship will always suffer from incorrectness (Wong 2005). To avoid misleading results, for this research the independent variable that measures entrepreneurship is total - early stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, and represents new business or owners / managers of a new business are considered to be the persons who paid the salary after the first three months (thus completing the start-up phase), up to 3.5 years or 42 months after starting the business. The other independent factor used in this research is the Growth Competitiveness Index, a framework used by the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report (GCR). The main objective of GCR is to review the capacity of the world’s economies to achieve sustained economic growth. Through the measuring of GCI the GCR represents the national competitiveness to which individual national economies have the structures, institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity (GCR, 2017- 2018).

This research is based on 33 countries which include transition and MENA countries for the period 2008-2016. The countries used in this research are: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Qatar, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE, and Yemen.

4. EMPIRICAL DATA AND ANALYSIS

A linear regression analysis is used for this research to concretely identify if entrepreneurship is an effective tool to decrease youth unemployment in transition and MENA countries. For this research the following hypothesis was established.

H: The higher the TEA ratio, the lower the youth unemployment ratio

The first step of the analysis is to define a suitable technique for the panel data. The Hausman test was used to define the model of the regression. According to the results from the Hausman test, the p-value is 0.000. Since p-value is < 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, which means that a fixed effect method is preferred. The unit root test of Levin, Lin & Chu was employed to avoid misleading results. With p-value = 0.0188, the test proves that the panels are at stationary. Another testing that was used in this research was the heteroscedasticity test and with Prob > ch2 = 0.000, the results prove the presence of heteroscedasticity. To deal with this issue, the robust standard error is used in this research.

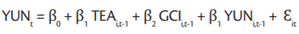

The following equation was established for this hypothesis:

YUN is the dependent variable and represents the youth unemployment rate, TEA and GCI

are the independent variables that represent the total-early stage entrepreneurship and growth

competitiveness index respectively.  is the lagged dependent variable i.e. the ratio of total

unemployment from the previous year. This variable exists in order to remove the serial correlation,

t represents the time, i is the country index, β is the coefficients

for the independent variables and Ɛ is the standard error term.

is the lagged dependent variable i.e. the ratio of total

unemployment from the previous year. This variable exists in order to remove the serial correlation,

t represents the time, i is the country index, β is the coefficients

for the independent variables and Ɛ is the standard error term.

5. RESULTS AND DISSCUSION

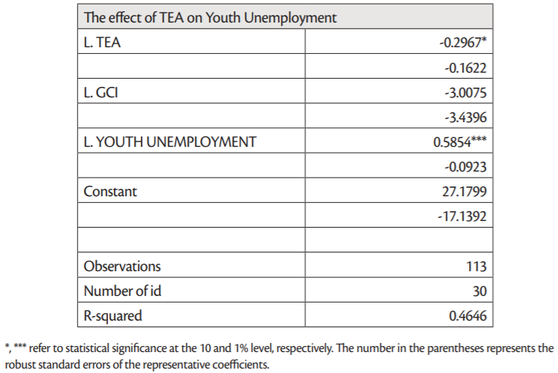

The panel data uses lagged data as control variables, since the agents in the economy may have a delayed response in unemployment (Stel et al. 2005;Koellinger and Thurik, 2012;Doulety, 2017). The test (F) is equal to 0.000 and R-squared = 0.4646, meaning 46.46% of the independent variables are explained by this model.

According to the estimated results we find a negative effect of GCI on youth unemployment, but it does not have an effect on the decrease of the youth unemployment since the p-value is statistically insignificant. However the effect of TEA shows to be statistically significant at 10% and its coefficient is negative. From the established results we cannot reject the test hypothesis (H), since it is empirically supported. According to the estimated panel data, for 10% increase of new entrepreneurial companies youth unemployment rate decreases for 0.2967. Lately many young individuals have started to see their future outside their own countries, especially young people from transition countries. The huge number of young going abroad has started to become a serious issue for countries such as North Macedonia and other Western Balkan countries.

Different programs have appeared for smoother integration of youth in the labor market, with one of them being entrepreneurship. This observation may indicate that youth who are still new in the labor market are more interested in starting their businesses during the time of unemployment, which empirically supports the idea for promoting entrepreneurship among young individuals. This model confirm the theory mentioned before (seeSchoof, 2006;Rotar, 2014), declaring that youth who are still new in the labor market are more interested in starting their businesses during the time of unemployment. However, the insignificance of GCI can indicate that young people are more risk taking by not taking into consideration the willingness of the institutions and the macroeconomic environment. Even though the data show that TEA has a positive effect on the decrease of youth unemployment, according to the literature review, young individuals that want to become entrepreneurs face difficulties such compulsory military service and lack of support of financial institutions, since young people do not have credit history or assets to save as collateral for obtaining loan, so they are forced to require help from relatives, family and friends for starting a business.

In order to support the youth entrepreneurship the transition and MENA countries should engage different programs to increase the level of entrepreneurship among young individuals such as financial support, grants and other business program support for young people up to 29 years old. The government should also engage in programs for education, trainings and mentoring. The entrepreneurial education should be spread among young individuals in order to foster innovation and innovative thinking. Furthermore, the governments should find ways to encourage exchange and knowledge transfer between the university, industry and the local communities.

6. CONCLUSION

Studies prove the importance of young individuals in the labor market. They are many times stated as the future of the country, and those who bring enthusiasm and new ideas. Even though we cannot neglect their importance, studies prove that their transition from school to the labor market faces many obstacles, since they have a lack of skills and experience; so many young individuals try to integrate in the labor market through entrepreneurial activities and by starting their own business. The literature review supports this action of young entrepreneurs stating that young individuals are keen to work for themselves and expose their business ideas. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship of entrepreneurship with youth unemployment in 33 countries, which includes the transition and MENA (Middle East and North Africa) countries for the period 2008- 2016. This research confirms that entrepreneurship can be used as a tool to integrate young people in the labor market in transition and MENA countries. However, the governments should engage more in business support programs through offering financial grants for young entrepreneurs, and engage more in entrepreneurial education, training and mentoring programs. Further research should be established on the influence of entrepreneurial education among young people, and the long – term influence of entrepreneurship on youth unemployment rate.