INTRODUCTION

Kopački Rit is a wetland area situated in the region of Baranja in the North-East Croatia, named after village Kopačevo. The village, which is mostly inhabited by ethnic Hungarians, is situated in the very corner of the “Drava Triangle” which is another synonym for Baranja. Croatian Baranja (Hungarian: Baranya) is a triangle demarcated by the Drava and the Danube rivers in the south and the east, and by Hungarian border in the north. The Croatian territory covers one third of the area, whereas other two thirds lie across the border, on the territory of Hungary. There is no certain evidence of the origin of name Baranja, but in Hungarian, it may mean bor-anyja or mother of wine (Labadi 2012:5) and in Croatian bara(nja) or pond. However, both names describe it well because it encompasses both the wetlands in the south and the loess terraces in the north, where vineyards are situated. Kopački Rit itself is one of the largest fluvial marshy plains in Europe (Bognar 1984:5). The large depressions permanently filled with water i.e. lakes, periodically flooded areas, ponds, canals, and waterways containing water streams are particularly important (Mihaljević 1999:11).

According to archaeological findings from the Stone Age, it is evident that the area of Kopački Rit was exceptionally rich with fish (Mihaljević 1999:176). Thus, it is not surprising that fishery has been developed from ancient times. A Hungarian ethnographer Karol Labadi mentions documents from the 13th century on fishing in this area namely, a document from 1212 which divides the area into three fishing zones, and a document from 1299 on fish farming in Kopačevo (Labadi 2010:6, 64, 65). Traditional fishing, as practiced by the villagers from Kopačevo in the neighbouring wetlands of Kopački Rit, and the delta of the Danube and Drava rivers, is a unique phenomenon, conditioned by both geological and hydrological conditions of the area where it takes place and is inseparable from. As a result of this conditioning, a special method of fishing has been developed when it comes to the technique, a specific toolset that is used and the customs, as is described by Labadi in detail (Labadi 1987:61–77;Labadi 2010:64–93)

Thirty-odd years ago, access to the Kopački Rit area was limited, the ban extended to the local population who were not allowed to fish there without providing a sound reason, despite the fact that it has been their cultural and natural environment for centuries. Even though the area was proclaimed a Managed Natural Reserve in 1967 and a Nature Park according to the Environmental Protection Act from 1976, a ban on commercial fishing was introduced under the Croatian Institute for Nature Protection (CINP) Resolution from 1984 (Mihaljević 1999:134). At that time the ban of fishing did not appear to be a serious problem for the locals. Professional fishermen were transferred to other posts and locations as stated by Lacko and Takač (Mrkonjić 2013a), while in the second half of the past century people tended to migrate toward cities. As a result, the population of Kopačevo village decreased by 20% between 1961 and 1991 (Labadi 2010:17). On the other hand, fishery was perceived only as a commercial and conventional activity. In other words, it was not seen as traditional, and its cultural value was not recognized at the time.

Still, as Mihaljević explains, the habits of the locals could not be changed in such a short time, so the permanent struggle against illegal fishing in Kopački Rit reserve has gone on until today (Mihaljević 1999:137). At present, the restriction appears to be an obstacle to a sustainable socioeconomic development of the village and its residents, particularly in relation to rural tourism and the Hungarian ethnic minority's cultural area preservation. Traditional knowledge is disappearing, especially the unique fishing technique, fishing tool manufacturing, boat building and consequently lots of other skills related to nutrition, housing, etc. The Kopački Rit Traditional Fishing Society (TFS), an organization of local activists, has established a knowledge transfer system, collected documentary material and artefacts, while seeking to protect the traditional skills as cultural property and restoring a right to limited scope fishing as a tourist attraction and an environmental monitoring and protection measure.

The wetlands, which had been created by the meandering rivers of the Danube and the Drava for over 800 years, as documented by fishing (Labadi 2010:6, 64), were preserved due to coexistence between man and nature. Without maintenance, the meanders are disappearing in a natural cycle of riverbank erosion and plant deposits (Đisalov 1972:101). Consequently, the area has lost more than two thirds of its watercourses in the past 30 or 40 years, according to the local estimations1. This is a threat to entire biological chains, as a new meander creation is prevented by hydrotechnical regulation on waterways or illegal reconstructions, as explained by Davorin Marković2, while traditional activities, including fishing, navigation, and cleaning of the canals and ponds are prohibited by law.

However, a public institution managing the area plans to rehabilitate the ecosystem by dredging the canals, as it does occasionally (Mihaljević 1999:11–12), in spite of a declarative injunction on “all economic activities3and interventions in nature”. This declarative injunction is the main “reason” or rather an explanation for the fishing ban affecting the locals. On the other hand, the question remains if traditional fishing is indeed a possible environmental threat since the area had remained preserved during hundreds of years of fishing practices that took place before the restriction. These inconsistencies in historical facts and recent practices lead the authors to conduct a research on possible ways to protect the natural and cultural heritage and use it in tourism as a key driver of sustainability, which resulted in this article.

The aim of the article is to present the environmental, cultural and economic sustainability of a possible revitalization of traditional fishing and other related traditional activities in Kopački Rit. After historically-oriented introduction, we first explain our research questions / hypotheses and research methodology. Then we provide the analysis of the research data, and discuss them according to the local views on the traditional ways of life, the cultural value of fishing, tourism potential and environmental issues. The article concludes with questioning the controversy of traditional fishing restrictions and with the hope to protect this intangible heritage in order to achieve sustainable development of Kopački Rit.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS / HYPOTHESES

The premise of this paper is the great importance and intrinsic value of the cultural heritage of the Kopačevo village (Conservation 2013), primarily of the unique fishing technique, fishing tool manufacturing and boat building, which are disappearing nowadays due to the late 20th century ban on fishing. The questions to be addressed include whether the protection of the intangible and tangible natural and cultural heritage and its usage for tourism purposes is possible at all, and if yes, in what ways. Is revitalization of traditional fishing in Kopački Rit environmentally, culturally and economically sustainable?

In support of the initiatives (Društvo 2012) for Kopačevo adaptation into a fishing village, the Osijek CDMC of the Republic of Croatia states:

“The Conservation Department in Osijek supports the Tourist Guide Association's4 initiative for Kopačevo adaptation, as well as the preservation and presentation of the traditional heritage in an appropriate manner.

The Š. Petefij Street and Ribarska Street in Kopačevo have been preventatively protected by the aforementioned department (from 2005 to 2008), yet due to many inappropriate renovations and new constructions the department gave up the protection of the historic entity. Our goal back then was the very renovation of rural households in their original form and the regulation of new construction. The protection of selected representative examples of traditional construction on those streets is considered today.

The Conservation Department considers the protection of a traditional boat – the čikl – to be of great importance because it is an important part of this region's historic and cultural heritage. Unfortunately, until this moment no manufacturer of wooden čikls, whose form and dimensions were in accordance with those of traditional boats, has been found.

We support your initiative and the inclusion of all the competent institutions in this project. Presenting this content and making it a part of the tourist supply does not only enrich it with valuable material but also brings intangible cultural heritage to the foreground, which in turn helps preserve traditional values and arts of the local community. We consider this project to be valuable in terms of contributing to the improvement and popularization of traditional heritage and natural values of the whole of Baranja.” (Conservation 2013)

The above mentioned support reflects the fundamental reasons why HITC suggested that the Croatian National Television (HRT)5 make a documentary about the traditional fishing in Kopački Rit thus making a record of the disappearing generation of old Kopačevo fishermen, who possess these traditional skills. The attempt to document the heritage, which is likely to disappear in the short term, brings us inevitably to the question why it is actually disappearing. One of the possible answers is that the prohibition of traditional fishing and other traditional activities in the wetlands, e.g. harvesting of reeds, affects a whole chain of related skills and knowledge from nutrition to housing. This in turn raises another question, namely why is that part of a valuable tradition prohibited. It seems reasonable because a nature park is a place meant to preserve the “untouched” nature, and fishing is a kind of harvesting.

Based on the brief historical review and evaluation of the respective heritage by CDMC we would like to put forward the following hypotheses:

Fishing is sustainable. There is no historical record or other evidence that traditional fishing is harmful for the certain area, in terms of nature park, as it is defined in law. Fishery in this area had been developed practically from the Neolithic period (Mihaljević 1999:176), and it was documented as early as 1212 (Labadi 2010:6, 64). It persisted even under the Ottoman rule in the 16th and 17th century, and 19th century (Labadi 2010:65), until the modern times, in more or the less same extent (Aurel 1937:7;Oreskovic 1957:33), causing no obvious changes in the natural environment in question.

The traditional fishing is beneficial for the wetland of Kopački Rit. This area is considered a natural phenomenon, created and preserved in coexistence between man and nature.6Preserved traditional knowledge and habits still have a role in local life and sensibly support balance between nature and culture.

The traditional knowledge, especially traditional fishing in Kopački Rit as a unique phenomenon, can be used for tourism purposes. Especially given the fact that Baranya is the most successful tourist micro region in Eastern Croatia, predominantly based on natural and ethnological heritage (AGROKLUB. 2015), with Kopački Rit and ethno villages being the most visited destinations, which is acknowledged by CDMC in their support.

RESEARCH METHODLOGY AND ITS ASSESMENT

Due to the very complex circumstances (described later), the data we used in this paper were collected first by the in-depth interviews, and only later by the survey, mainly among the population familiar and interested in the subject of research, the traditional fishing and the possibility of its revitalization. When it was possible, we also collected documentary material, mainly old photos, and we listed and photographed some of the material items related to the topics, belonging to the participants or to the members of the families. Beside notes and audiograms, in the further analysis we also used the transcripts of interviews and statements taken by HRT during the recording of documentary.

The research actually began spontaneously in December 2012 while we were looking for fishermen, fishing tools, and locations for the demonstration of traditional fishing, making fishing tools, maintaining boats and other related skills for a TV documentary. It was conducted in the Baranja region between 2012 and 2015, particularly in the area of Kopačevo village, but also in the city of Osijek, and in the broader Croatian Danubian Region (from Vukovar and Šarengrad to Ilok), as well as in Apatin and Bački Monoštor in Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia) as an area of a unified fishermen’s activity (as Apatin once housed the Anglers’ Central Office, in an area that still belongs to the Republic of Croatia’s cadastre7).

At first the community responded positively to the idea of demonstrating traditional fishing skills for a TV documentary. We even managed to collect digitalized old photos from the local office and have been given a list of names with basic information about the possible fishing demonstrators for the documentary. However, a few weeks later, we met with very strong resistance. A meeting to take place in a hunting lodge with all those who have any knowledge about traditional fishing and tools which had been arranged in advance, was first postponed and then cancelled without explanation. Some individuals, with whom we had previously arranged the meetings, later avoided us, while some very harshly rejected cooperation. It soon turned out that a serious conversation about traditional fishing was considered a taboo in a way.

In the first interviews with those who were willing to talk about the traditional fishing, or more precisely about the ban which was imposed rather than about the fishing per se8, we could see that the current situation was only accepted on the surface. Beneath it lay a suppressed collective feeling of humiliation caused by the prohibition of fishing, perceived as unfair and unreasonable since the activity was regarded as a cultural heritage and an expression of the community’s identity. Indeed, we found out that in the past 15 years9 there were some attempts and promises of granting the permission for limited fishing to the Kopačevo residents. However, nothing happened, so the problem deepened resulting in even greater frustration, distrust, and ultimately resistance. Therefore, the only possibility left for communication with those who were willing, were individual meetings and interviews.

In January and February 2013, we conducted 15 interviews aimed at discovering how many people with the specific skills we could find and whether they had any traditional fishing tools, photos, documents or other materials. Taking the situation and the sensitivity of the topic into account, we felt it necessary to use unstructured in-depth interviews to allow the respondents to choose their own dynamics, the subject of conversation, and to what extent they were ready to discuss it. At the same time, we maintained focus on the topic and the dynamic by watching the old photos of traditional fishing which led to conversations about locations, traditional fishing tools, fishing techniques, people in the photos, and then about their families, about what they were doing today, and if they were keeping any of the traditions. In such a way, we were able to get more contacts and find the local people who possessed the knowledge and/or traditional fishing tools, old photos or documents. Moreover, we managed to date dozens of the collected photos and identify and/or confirm locations and names of the people in them (as inPicture 1).

People also responded to various activities undertaken as part of the traditional fishing revitalization project which was only experimental. Producing a documentary about traditional fishing, the reconstruction of traditional boat building skills, preparing an exhibition of old fishing photos and fishing gear, the founding of the TFS and finally broadcasting the documentary on the national television (U mreži 2014) brought about significant changes in the communication style and attitudes to the project.

During the research in the wider area we found the last retired boat builder who had made the boats in the 1950s for all fishermen of Apatin Fishery Centre, including those from Kopačevo.10 He helped us make the first reconstruction of a traditional boat. This appeared to be very important because the building of a boat and especially its launch in the lake Sakadaš (Latinović 2013b:18) had cult significance to a certain extent. The building of a traditional boat was a kind of initiation of the boat constructor and his acceptance to the tribe as a master of one of the important fisherman’s skills. Also, the launch of the boat in the lake Sakadaš was a symbolic representation of the fishermen returning to Kopački Rit. Subsequently, we noticed significant improvement in the communication with the locals, and growth of their confidence in the project. Similar happened after setting up the exhibitions about traditional fishing in a local coffee bar (Latinović 2013a:20). Previously displayed photos with hunting motifs were first partially and then completely replaced by those of fishing.

A step forward in the community’s acceptance of the project was certainly the founding of the TFS, which has put in place a system for the knowledge transfer as one of the preconditions for intangible cultural heritage sustainability. One of the prerequisites for becoming a full member of the TFS is having expert knowledge about traditional fishing techniques, making of fishing tools and boats, and one must also earn the title of Fisherman (Kopacki 2013:3).

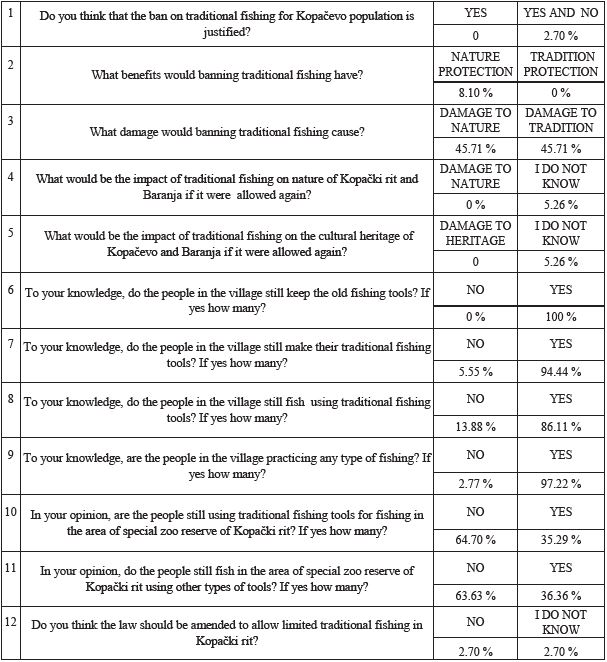

Finally, we conducted a survey in Kopačevo in June and August 2015, which looked into the views on traditional fishing: how justified the prohibitive measures were; what effects traditional fishing had; its present day practices, and opportunities for its revitalization. The survey included 38 respondents (95% male), average age 43 years (26% did not want to disclose this information) ranging from 22 to 67, mostly locals of Kopačevo, namely 76.3%, while 23.7% did not declare their place of residence. According to the 2011 census, the village population was 558 residents in 226 households (Census 2011, CSB). The sample is relatively small, nevertheless the goal of the survey was not to investigate the public opinion, but, as was pointed out in the beginning, to identify the possibility and potential for the preservation of a part of the intangible cultural heritage. Therefore, it was important to carry out a survey among the segment of the population which could be expected to actively participate in the project. Taking into account the age and gender structure, we can assume that the participants were representatives of their families and that the survey encompassed 38 households, which is about 17% of the total.

It is important to bear in mind that the traditional fishing is still a sensitive topic which many people do not want to discuss, although in the two years of the project a definite attitude shift was observed. Also, there were no material conditions for surveying the houses, for which it would have been necessary to train more people, particularly bearing in mind the sensitivity of the topic, a traditional, somewhat closed community, and a significant language barrier. The latter was particularly noted during the survey. Namely, the native language of most of the locals is Hungarian, and especially older population

do not fully understand Croatian. According to the analysis, this affected the answers to some of the questions. These were the main reasons why the survey was conducted among the members of the TFS and in the local coffee bar, which is the centre of Kopačevo social life where both hunters and anglers gather.

DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Local Views on the Traditional Ways of Life – Including Fishing

Very high, almost absolute, percentage of the respondents declares that in their opinion there was no reason for a ban on traditional fishing; 97.29%, said that there were no benefits from it; 91.89% stated that the fishing would have a positive impact on nature, and 94.73% on cultural heritage. Likewise in question 12, 94.59% of the respondents declared that the law should be amended to allow traditional fishing in Kopački Rit.

However, not all answers were so straightforward. In fact, the answers to question 3 represent the only divergence in opinions according to other questions, since significantly fewer respondents, namely 45.71% stated that the ban on fishing was harmful to natural heritage and 45.71% stated it was harmful to cultural heritage, whereas surprisingly as many as 37.14% said that the ban was not harmful. However, these negative responses also contradict the responses to questions 1, 2, 4, 5 and 12 and it was estimated that they should not be taken into account12. If we exclude these respondents, 72.73% stated that the fishing ban was harmful to natural heritage and 72.73% stated it was harmful to cultural heritage, which is in line with the answers to the rest of the questions (which to some extent act as the control) and the conclusions of earlier research.

Furthermore, a very high percentage of the respondents, i.e. 86% to 100% answered positively to questions 6 through 9 about the keeping, making and using traditional fishing tools and fishing practice in general. The data on the number of people who are keeping or making tools and practicing fishing are somewhat more problematic, since this is a sensitive issue and the majority of respondents therefore abstained from answering. The number of people with such knowledge in gathered responses varied from very small, 1-2 people, to very large, 50-100 people. Moreover, some people formulated their answers in percentages, which were taken into account, while others gave descriptive answers, i.e.: a lot, the whole village, quite enough, whoever gets the opportunity, etc., which were not taken into account. If these answers could be quantified in some way and taken into account, the result would be a higher number. Therefore, it can be assumed that the reported numbers of people who have or make fishing tools and practice fishing is a reliable lower limit13.

The most delicate group of questions, i.e. 10 and 11, were certainly those pertaining to the illegal practice of fishing in the restricted area of Kopački Rit. Here, the majority of the answers, 64.71% and 63.64%, were negative, whereas only a small number of the respondents specifically stated how many people, in their opinion, were practicing fishing in the protected area. The data are indicative because it is well known to the public that some people from the village are prosecuted because of this practice, and there is no doubt that it exists.

In question 14, which was an open question about traditional fishing, the following comments were given:

- When traditional fishing was practiced, the swamp was cleaned, and now it's muddy.

- We have to show our tradition to others.

- If fishing was harmful, today these "so-called" guardians of the park Kopački Rit would not have anything to guard!

- Fishing should be allowed in Kopački Rit because it would be easier for the rangers to keep the marsh free of poaching and poachers. Fishermen would keep their tools and the marsh at the same time. Also, because of the local people’s income.

- Allow people to live like in old times.

- Traditional fishing was not harmful to Kopački Rit even for a moment. Rather, it was beneficial regarding the balance of fish stocks, sustainable development of ecosystems in terms of water flow regulation, removing collapsed trees, harvesting of non-native species, removal of inadmissible tools made by poachers, regulation of hazardous bird species, for example, cormorants which cause incalculable damage to fish stocks.

- Traditional fishing has been an inseparable part of life in Kopačevo, its honour, and pride.

- According to the Ramsar Agreement, each Party shall allow the continuation of the traditional life of the local population.”

The obtained data are consistent with those from in-depth interviews conducted during the preparations for the making of the HRT documentary in 2012 and 2013. Additionally, the results confirmed that there were both, the necessary conditions and the will to revitalize traditional fishing, as was already indicated by the act of founding the TFS.

Cultural Value of Fishing

At the beginning it should be said that there are no reliable (i.e. quantitative) means for empirical representation of the cultural value (Throsby 2010: 148). However, according to numerous historical facts and references in scientific and popular literature, traditional fishing of Kopački Rit is quite distinctive and has had crucial impact on how the Kopačevo village community perceives itself both culturally and economically. Moreover, it was vital for the preservation of the surrounding wetlands. In dependence with the hydrological conditions of one of the largest floodplains in Europe, 14

it forms an exceptional heritage, a sort of a cultural capital, worth to be preserved.

Let us mention only the most outstanding tolls and fishing techniques which reflect traditional fishing approach (for detailed study on the traditional fishing of Kopački Rit seeLabadi 2010: 64-92). Vejs or vejsze, meaning fence or yard in Hungarian, is a kind of enclosure made of reed and stuck into the bottom of a pond, which fish can enter but cannot find a way out of. Fish can live, feed, and hatch therein, while baby fish can leave it due to a limited density of reed “bars”. It is not an obstacle to navigation, and if abandoned, it falls apart and decomposes before the next season. Since it is non-invasive and very selective tool, made entirely of organic material, it reflects all the essential characteristics of Kopački Rit traditional fishing.

However, the fishing is strongly related and bounded with the rest of Kopačevo traditions and culture. Not only because of high income, best illustrated by the facts from the 19th century when the village church was built by the single annual donation of local fisherman, or by the record that the coins for the single payoff of the fishermen weighted six tons, and landlord needed 6 oxen for their transport (Labadi 2010: 5-15). Firstly, fishing influenced a nutrition; its dependence on fish has been a commonly important mark of Hungarian culture, as it is described in the article “Fishy Country – On the Medieval Traditions of Hungarian Cuisine” (Bittera 2015). Moreover, part of the local cuisine is based on the second class fish, so-called white fish, so it depends on traditional fishing because the certain species are not commercial, and could not be find on market. But it is not only cuisine that is related to fishing. Cleaning of the canals and its surrounding of fallen trees, necessary for navigation and fishing, but also crucial for circulation of a fresh water vital for the fish, provided fishermen with the firewood. Harvesting of reeds, important also as a measure for preventing the eutophisation, provided a material for fishing tools (vejsze), as well as a construction material – thatching reed, which has strongly affected local architecture and has been recognized as energy efficient and environmentally friendly.

Other important reasons why the traditional fishing is so deeply rooted in the collective memory of the whole community, beside the fact that it was also the job of many inhabitants, are the arable land and the maintenance of the canals and lakes. As explained in the interview with Janoš Baka, fishing engineer and the director of former fishing cooperative, the residents of Kopačevo have had less arable land (Getto 2002:9) than other villages in the area. Thus they have been oriented to the wetlands and concerned for their land; the word “rit” (Hungarian reet), meaning field, illustrate their attachment to it. This is one of the reasons why the ban on fishing and other wetland activities hinders rural development of Kopačevo.

Another reason why fishing was important for the whole community is reflected in the fact that maintenance of the canals, done by the fishermen, was not important only for fishing and navigation, but also served as the flood prevention, known and recorded from the medieval times (Labadi 2010: 65;Fodor 2005: 5;Molnar 2011: 5;Czsako 2012).

Fishing tradition is still very vivid and therefore it could be argued that it is culturally sustainable, especially since the longevity of the practice despite the ban indicates successful bottom-up heritage management. Numerous old toolkits and fishing methods are still being used in practice, and there is a vivid remembrance of the fishing tradition in the area among both the old and young residents. This was a motivation to record the data on this tradition as well as collect the materials (which was done from 2012 to 2015, during the making of a HRT documentary, when we collected oral traditions, documented the skills of building wooden fishing boat – čikl, and established an ethnological collection about traditional fishing).

In the context of its evaluation, it should be pointed out that traditional fishing in Kopački Rit fulfils the criteria for legal protection as intangible cultural property (Ministry 2013). Its protection, beside the preservation of heritage, may also improve socio-economic position of the local population, which is in accordance with positive international legal instruments concerning the tolerance between communities, having in mind that the certain heritage belongs to the Hungarian minority in the Republic of Croatia, as it is documented in present research. Furthermore, community identifies itself with fishing and regards it as the most important part of local cultural heritage, as it strengthens the feeling of belonging and of continuity based on collective memory. Finally, fishing tradition is deeply rooted in a community, and it is still vivid in spite of the legal restriction, and considering its uniqueness, it is an important contribution to the diversity of cultural heritage of Croatia.

Considering the importance of traditional fishing – it does not only have a cultural value, as discussed above, but could also be a key feature of sustainable management of the Nature Park – this practice also has a potential for tourism development of the area. This could even be enhanced by the protection of the Kopački Rit traditional fishing as intangible cultural property, which on the other hand implies implementation of protection measures including the right to limited fishing in its cultural and natural environment.

Potential for Tourism

Baranja is a micro-location that displays all the characteristics of Eastern Croatia (Slavonia, Baranja, and Syrmia), which renders it especially suitable as a representative site of any local or regional heritage. Surrounded by rivers and wetlands, it encompasses flat arable land as well as vineyards, and it can be described as the land of bread, wine, and fish. Due to the fact that the last generation of residents who remember the village of Kopačevo as a fishing village has been disappearing – and with it the material traces of this centuries old lifestyle as well as the ancient landscapes of Kopački Rit – the locals established the Association for Heritage Interpretation in Tourism of Eastern Croatia (HITC). The Association’s aim is to adapt Kopačevo into an ethno fishing village, as well as a place for the preservation and presentation of traditional heritage. They felt necessary to launch a procedure to protect and preserve traditional fishing in this area as a unique phenomenon in Europe (Društvo 2013).

Conservation Department of the Ministry of Culture (CDMC) supported this initiative of the HITC, and the same applies to the Pragma, Science and Culture Association of Hungarians in the Republic of Croatia (Pragma 2013) and Bilje Municipality (Bilje 2013). Another HITC initiative, entitled Baranja Trilogy, was simultaneously launched in order to present the diversity of local heritage, as it focused on three ethnographic villages and their ways of life, namely Kopačevo with its fishermen, Karanac with its farmers, and Zmajevac with its vintners (Društvo 2013). The rationale behind the initiative was the underlying awareness of the need to protect the most important natural and cultural landmarks in Baranja under a coherent and harmonized project (Društvo 2013) and use them for tourism purposes, which was supported by the Osijek-Baranja County (OBC) (Osijek 2013).

The initiative envisaged the establishment of an Ethnographic Fishermen’s Park, a multipurpose facility which would predominantly be a guest reception and resting facility with a showroom and an event area, but would in addition serve for presentations and exhibitions of local heritage. It has been planned as a central thatched wooden penthouse that could accommodate 100 visitors. It would have been appropriate for rest, lectures, and adequate food and beverage service. In addition to a large-sized penthouse, two smaller-sized penthouses for barbecuing have also been planned. The reconstructions of a thatched wooden fishermen’s hut and a traditional thatched refrigeration facility, where the visitors could see the process of depositing ice during the winter season, has been planned to be located on the south side, and would represent the first facilities of their kind in this area and beyond. The Ethnographic Park would be encircled by a bricked promenade and a pathway leading to a nearby canal with water access where visitors could see traditional boats and exhibits of fishing tools (nets, coops) drying on the land (Društvo 2013).

The Park complex also plans to exhibit an ethnological collection (whose reconstruction is ongoing). The collection used to be kept in the nearby Community Centre up to 1991 and was devastated during the occupation, along with the zoological collection. Thanks to a private intiative, the latter has already been reconstructed and exhibited in a neighbouring building on the southern side of the park.

Allowing the traditional čikl to be used in culture, tourism industry, and sports would ensure its permanent and sustainable protection as intangible cultural heritage of the area (Živaković-Kerže and Mrkonjić 2014:294). Moreover, the boats could become a part of the Kopački Rit Natural Park tourist supply, available for individual visits and adventure tourism. Under the Kopačevo Ethnographic Fishermen’s Village Project it is planned to set up a workshop for the demonstration of the traditional fishing tools and building of vessels as a way to preserve and transfer the skills. Many other recreation, culture and tourist programmes based on the čikl could be developed and offered for sale, including rowing competitions or visits to the tourist destinations along the Drava and the Danube by boat, combined with other modes of transport.

Even today, the residents still show a keen interest in fishing. This is of crucial importance for the preservation of traditional skills. On the other hand, activities connected with traditional fishing could spark the interest in fishing itself as well as in learning about the old fishing tools and techniques among the youth. Ever since Kopački Rit was declared a Nature Park because of its landscape and cultural value (Official Gazette 2013/80), it has been possible to rehabilitate traditional fishing within rural tourism and make it an important and high-quality part of the tourist supply.

Environmental Issues

As described by Nikola Đisalov in as early as 1972, the Danube flood zones are rapidly deteriorating. The backfilling of the backwaters, streams and ponds in the floodplain as well as gradual uplifting of the flooded terrain and its waterlogging undermine the role of the flood terrain for mass insemination and breeding of important fish species in the Danube (Đisalov 1972:101). Moreover, if there are no floods during the flood season, the fishing is poor (Plančić 1952:9). This indicates that the main problem for the fish stocks may not be the fishing per se, but the disappearing of the flooded areas, e.g. wetlands. This is partly due to the artificial backfilling of canals and reforestation with poplars (Đisalov 1972:101), but also because of fluvial and organogenic-marshy sedimentation, the latter being more prominent (Bognar 1984:5).

Despite the fact they are not represented on NPPI official web site (NPPI 2015a), cormorants are in fact the main attraction for the tourists who come to Kopački Rit because during nesting they “occupy” tourist boat route. Other birds can only be seen occasionally, depending on the season and water levels, and usually in smaller numbers (NPPI 2015b). However, the cormorants are in fact an allochthone and invasive species. Although this is not officially stated, it is indicated in a study conducted by Đorđević and Mikuška in 1985. Closer analysis on ponds showed that cormorants were feeding on primary fish stocks (such as carp) in 93.49%, and only in 2.72% on the so-called "fish weeds", less qualitative allochthone fish (Đorđevic 1985:75).

Darko Getz, an environmentalist who worked in Kopački Rit during the 1970s and 1980s when the area was protected, now calls for categorizing cormorants as "commercial fishermen", based on the quantity of fish they consume and the legal protection they enjoy, while (human) fishermen are left to fend for themselves (Getz 1998a: 23). Hence, we asked Davorin Marković, the head of the landscape department of CINP, about a possible impact of hydro-technical regulations, invasive bird species, and traditional fishing on the Kopački Rit Nature Park. The replies he gave were in line with the statements of the interviewed local fishermen from Kopačevo village, the survey results, and other sources. He stated:

“1) It is true that present day canals and lakes are the remnants of earlier meanders of the Danube and Drava rivers. In fact, the whole area represents a retention basin for the Drava and Danube rivers, which receive flood waters in the rain season. Their survival was threatened by illegal reconstructions of the entrance and exit canal “gates.” What should be done now is to open the entrance and exit “gates” to establish a normal flow regime.

2) At present, it is thought that some form of “purification” and deepening is necessary. However, it should be done only to an extent and only in places where deepening might be useful. A study that is being designed should corroborate this. In fact, a thick stratum of plant, animal, and mineral deposits has been created in the canals and lakes, which obviously does not have a positive effect on the wildlife. Due to increased pressure under the conditions of hypoxia and often apoxia, high concentrations of detrimental nitrogen and carbon compounds are also being produced. Therefore, it is very important that the study proposes high quality measures regarding sludge deposits in order to avoid any harm to the existing flora and fauna.

3) Traditional fishing that is strictly limited cannot harm the fish stocks in any way. Quite the contrary, it might have a positive effect in terms of attracting tourists and depicting traditional lifestyle of the wetlands. It is crucial to emphasize that all this needs to be encompassed by a high quality study, whose proposals and recommendations must be adhered to. […] 15

Davorin Markovič also advocated for an expert study to define historical background of fishing (from traditional toolkits, fishing methods, and lifestyle to the fish stocks); current situation (biodiversity, physical and chemical status for each body of water, flow regimes for at least 50 years, and precise ichthyologic data and activities), as well as future outlook and possible impact models. In his opinion, the study should recommend the measures to guarantee sustainability. 16

Another Marković’s brief letter on the cormorants17 indicated that the Kopački Rit Nature Park could have been on the verge of an environmental disaster due to ignoring this problem and inadequate maintenance of the canals. This is in line with studies of several authors (Bognar 1984:5;Đisalov 1972:101;Mihaljević 1999:174).

Furthermore, Marković’s opinion on the harmlessness of traditional fishing is in line with the dominant local view of the issue, but also points to the absence of a study on the impact it could have on the wetlands. The issue is even more complex in Kopački Rit since the so-called “fish weed” (which is not consumed by the cormorants) mostly consists of crucian carp (babuška), another invasive species brought into the area in the 1970s.

Therefore, the invasive crucian carp (babuška) is competing with autochthonous carp (šaran) for the food and threatens its growth (Kajgana 1996:131). Furthermore, cormorants also almost exclusively feed on carp (Đorđevic 1985:75). This means the carp is doubly threatened and in danger of extinction. This fact was proofed by a Kopačevo fisherman Janoš Lacko, who in 1984 (from 26 August to 25 September) brought to the Šaran (carp) Fishing Cooperative in Kopačevo a total of 8.418 kg of different fish he had caught, out of which only 17 kg of fish consisted of an (indigenous) carp and as much as 7.679 kg fish of a crucian carp. With the help of the cormorants, the crucian carp obviously pushed out autochthonous carp in a mere decade, so fishing of the crucian carp could have even be seen as a way to keep the natural balance between different species.

However, traditional fishing was not selective; people fish all kinds of fish and used the 1st class fish for market and the 2nd class at home, mostly salted and dried (Labadi 2010:155; seePicture 2). Since preservation of fish ensured its consuming in all seasons, it greatly influenced local traditional cuisine.

Furthermore, by pulling their nets fishermen used to clean the plant deposits, which was the main cause of backfilling in lakes and canals (Bognar 1984:5). Also, the Kopačevo residents have traditionally had the right to collect fallen trees for firewood, which means that they only cut the trees down in case it was absolutely necessary (Sršan 1999:55), preserving the forestation of the area. Using nets was thus a way to prevent plant deposits. However, fishermen occasionally also dredged canals and lakes by pulling a steel rope. 18

CONTROVERSY OF TRADITIONAL FISHING RESTRICTIONS

The prohibition of the traditional fishing and other related activities in Kopački Rit poses a challenge to achieving cultural sustainability and economic development of the area. Whether the ban is reasonable or not, the fact (proved by the interviews and survey) remains that it is perceived by the locals as incomprehensible and unfounded as well as unfair for the local community.

Although the document titled “Information on the state of play and development programs for Kopački Rit Nature Park”, produced by the OBC, predicts future cooperation between the Nature Park Public Institution (NPPI) and the local population as well as educational activities (Osijek 2014: 10), so far not much has been done in that direction. The research – interviews with the locals as well as the NPPI Director – did not reveal any evidence of the planned cooperation. The document in question had been drafted for a session of various Nature Park stakeholders, namely OBC, NPPI, Croatian Forests, and Croatian Waters. It may therefore be assumed that the representatives of the TFS were not invited to participate, and neither were any other local or CDMC representatives in spite of the fact that OBC had previously expressed its support for the initiative to transform Kopačevo into an “ethno fishing village” centred on the traditional fishing restoration (Osijek 2013). Actually the previously described collective frustration by (what was perceived as) “unjustified” prohibition of fishing is also partially caused by the lack of cooperation and communication between the authorities and the local population, i.e. inclusion of the village community, and finally of the TFS as the Nature Park stakeholders.

As it was already mentioned, despite the injunction from 1984, which brought into effect commercial fishing restrictions under the CINP Resolution (Mihaljević 1999:137), traditional fishing practiced by locals was still legally allowed to fulfil their own needs (or tolerated to some extent). The area was proclaimed a Managed Natural Reserve in 1967 and Nature Park and Special Zoological Reserve under the Environmental Protection Act of 1976, but this did not affect the fishing in the area. Even today, fishing is not specifically restricted under the current Nature Protection Act (Official Gazette 2013/80). In the first Law on Nature Protection enacted in the Republic of Croatia in 1994 (Official Gazette 1994), fish and fishing were not even mentioned specifically. Instead, the ban referred to endangered animal species collectively. Moreover, article 62 of the current Nature Protection Act (Official Gazette 2013/80) stipulates only precautionary measures in view of sustainability when it comes to fishing, explicitly “taking wild species from nature”. Everything else, concerning the restriction on fishing in Kopački Rit, is regulated by the bylaws and documents adopted by different state institutions.

Furthermore, according to the Article 28 of the Regulation of internal order in Nature Park of Kopački Rit issued by the Ministry of Environmental and Nature Protection (Official Gazette 2000/77), “traditional fishing” as “commercial fishing” done “exclusively with traditional tools from the local area” is allowed on open waters and certain areas determined by NPPI, except in the area of the Special Zoological Reserve. This reserve is defined by the Decision on the Kopački Rit Nature Park Spatial Plan (Official Gazette 2006/24). Article 7, referring to this area, allows limited, organized and controlled visiting and sightseeing with boats, and touring of small groups on existing land routes (forest paths). Other activities permitted in the area include afforestation activities, optimal water level maintenance, building water regulation structures in order to maintain the Drava and Danube waterways, as well as technical and economic/commercial watercourse maintenance activities, regulation and building of the objects for nature protection.

Open questions remain, why the “traditional fishing” is equated with the “economic or commercial fishing”, and why all activities, listed as permitted, are considered as less invasive than limited traditional fishing. This is especially controversial due to the historical findings (seeLabadi 2010:65;Fodor 2005:5;Molnar 2011:5;Czsako 2012) that traditional fishing is at the same time considered as efficient “maintenance of optimal water regime”. Similarly, controversial is proclaiming the Special Zoological Reserve in the area adjacent to the village along the public road, as uninhabited – and therefore more “pure”, “untouched” – wetland area lies in the north-eastern part of the Nature Park. The area to the west has already seen a huge number of visitors, 30,000 annually on average (Poslovni 2016).

A proposition to restrict fishing in Kopački Rit, pertaining to the residents of Kopačevo, was published as early as 1955 in the Croatian Journal of Fisheries (Anonymous 1955:40). In the absence of the official explanation, the bottom-up speculations on the reasons for such decision highlight large catch of fish bringing fishermen considerable amount of income. As stated in the above mentioned journal, the need for fishing restriction was "justified" by the fact that the fishermen from the village prevented 500 tons of fish to return from the marsh back to the Danube by spreading 6.5 km of nets in an attempt to earn "too much money". It is also stated that they used nets with holes too small in places, thereby stopping baby fish along with bigger ones, but there is no information if the whole net was of the same type. According to the locals,19 this is an ancient technique and only the big fish is kept in the net; it is considered as a sort of fish farming, recorded as early as in the 13th century (Labadi 2010:6). However, this piece of information draws a bigger picture about how much fish there used to be until the restriction; furthermore, it is to be noted that people at the end of 1950s also started to fish for the fish factory in Apatin (Orešković 1957:32–35;Getz 1998b:470; Rečno 1965).

The factory was established in 1957 in order to process second class, so-called white fish, into fish flour and oil. According to Drago Orešković, factory CEO, about one-third of the catch was white fish, up to 30 tons in a single day, and there was no market for it, therefore they have been forced to return it to open water before they established the factory, and started to process it.. However, it was noticed in the following decades that selective overfishing of quality fish (e.g. carp and catfish) had caused biological imbalance, and a huge amount of white fish devastated natural sources of food for carp in flooded areas (Oresković 1957:33). Later, the factory started producing canned fish, and in the 1970s it began with nacre extraction from fish scales20 for cosmetics industry.

According to Labadi, fishermen from Kopačevo made a catch of biblical proportions in just five days of December 1821, i.e. 200 tons, and that similar amount of catch continued until Easter (Labadi 2010:65). Regarding the catch sizes in the past, but also the depletion of different fish species and categories in Apatin Fishery Centre area, we found some data in an article from 1937 (Aurel 1937:6). Jovan Močković,21 one of the last old fishermen and employees of the Apatin factory, also confirms that fisherman regularly caught considerable amount of fish, e.g. 250–300 ton of carp per year from the 1950s to the 1970s only in the area of Kopački Rit. According to a statement given by engineer Jovković, Centre Director, the average annual catch was about 1000 tons: 37% carp, 35% white fish, 30% pike, followed by perch, catfish, and other species. Second class fish, mentioned by Orešković (Orešković 1957:33), was completely exploited at the time. It was cleaned (as inPicture 2), salted and dried in Kopačevo as described by Labadi (Labadi 1987:35).

To sum up, there is no concrete (i.e. quantitative) evidence that traditional fishing in this area affected the environment – neither overfishing nor the use of specific fishing techniques – and negatively impacted the ecosystem. This claim is also supported by more than 700 references in the books, papers, studies and other sources about Kopački Rit.Mihaljević (1999) lists more than 650 references in his work “Kopački rit - pregled istraživanja i bibliografija” Despite that, the conservationists we consulted agree that a study on the possible impact of traditional fishing in Kopački Rit should be done.

In an interview for the Croatian National Television documentary (HRT 2013) Damir Opačić, NPPI director from Kopački Rit, agreed with the idea of protecting and nurturing traditional fishing, but on the other hand also suggested that it was not necessary to practice and preserve that skill in the protected area. When we claimed that traditional fishing was not harmful to nature whereas the bodies of water could disappear and consequently turn the wetlands into the fields if there was no dredging or pulling of the fishing nets as had been practiced there for centuries, he replied:

“You forget that meanders were created a long time before the creation of humankind, so human activity is not what causes Kopački Rit to be as it is. Our discussion on dredging vs. fishing is based on our assumptions that have not been scientifically proven. The measure stipulated by law is the economic activity restriction at least in the area of the Special Zoological Reserve, and in my opinion, it is completely reasonable. Also, the current (wetland) area which enjoys a certain category of protection [i.e. Special Zoological Reserve], represents only 25% of what existed in the past. There are other locations nearby, such as the Bilje Lake or the canal in the village, which are outside the protected area and are still suitable for fishing even closer to the village. In my opinion, these areas are sufficient and we in the NPPI are trying to attract visitors and looking forward to the area being visited and presented to the public more, but the Nature Protection Act is clear. In the areas of the Special Zoological Reserve no economic activities are permitted which includes fishing as a matter of our discussion.”

Although Opačić’s opinion given in the above mentioned interview should not be considered the official NPPI standpoint, it still reflects the common policy of the Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection of Republic of Croatia and a public opinion22.

However, meanders haven't been created before humankind, and there are parts of the canals and even lakes which were artificially made in the past, as Mihaljević explains: “During the course of history, the hydrography of Kopački Rit was mostly influenced by floods, but also by numerous hydrological works which define the current hydrological status” (Mihaljević 1999:173). Furthermore, the legislation concerning the matter of traditional fishing is not as unambiguous as claimed by Opačić. According to the Nature Protection Act:

A nature park is a large natural or partly cultivated mainland and/or marine area with ecological features of international or national importance, or with marked landscape, educational, cultural, historical, tourist and recreational values. (2) A nature park also has scientific, cultural, educational and recreational purposes. (3) In a nature park only those actions and activities are permitted that do not pose any threat to its essential features and roles. (Official Gazette 2013/80)

Since the traditional way of life, including fishing and related activities in Kopački Rit, is without a doubt a “cultural and historical” value of the area, as CDMC explained (Conservation 2013), it could be supported by NPPI and also included in their program.

CONCLUSION

Historical facts prove that the traditional fishing of Kopački Rit is quite distinctive and has had crucial impact on how the Kopačevo village community perceives itself both culturally and economically as well as on the surrounding wetland. In dependence on the hydrological conditions of one of the largest floodplains in Europe, it forms an exceptional heritage, a sort of a cultural capital, worth to be preserved. According to archaeological findings, fishing in the area of Kopački Rit has been practiced from the Neolithic period (Mihaljević 1999:176), and continuously documented from the 13th century onwards (Labadi 2010:6, 64).

Today the preservation of this heritage – fishing as well as related activities such as making tools, building boats etc. – is threatened by the ban on traditional fishing. The ban poses a challenge to the cultural sustainability of the area, as well as diminishes potential for the economic development. The paper points out the lack of indicators to justify legal restriction; none of the references from various interdisciplinary literature and written sources about Kopački Rit claims that traditional fishing negatively impacts the environment. On the contrary, numerous references (e. g.Sršan 1999:55;Labadi 2010:6, 64;Fodor 2005:5;Molnar 2011:5;Czsako 2012; see alsoMihaljević 1999:24–28) prove that the wetland of Kopački Rit is shaped and preserved in coexistence between man and nature. Even more, without that coexistence, the nature park, as it is being managed, becomes unsustainable due to the backfilling and eutrophication processes as well as hydrotechnical regulation (Bognar 1984:5;Mihaljević 1999:135–136). Indeed, the Nature Protection Act stipulates that nature parks are partially cultivated areas (Official Gazette 2013/80), and envisages the need for its maintenance (Official Gazette 2006/24). As shown in the article, traditional fishing and other activities related to the traditional way of life have had a crucial role in cultivation and maintenance of the landscape for centuries (Labadi 2010:65;Fodor 2005:5;Molnar 2011:5;Czsako 2012). Traditional fishing in Kopački Rit shall therefore not only be preserved as a valuable cultural heritage, but also as a manner of environmental protection and a monitoring measure of the Kopački Rit Nature Park. Having in mind that the Natural Park is also a cultivated area – due to (past) traditional fishing and other related traditional activities – traditional fishing shall be perceived as an inseparable part of the "cultural value" of the Park, as defined by the Law on Nature Protection (Official Gazette 2013/80).

Taking into account that the Kopački Rit Nature Park, with its annual average of 30,000 visitors (Poslovni 2016), is the top tourist destination in Eastern Croatia, while the neighbouring ethnographic village of Karanac was the most successful Croatian rural tourism destination in 2015 (Croatian 2015), it is clear that Baranja tourism is based on the natural and ethnological heritage. Kopačevo represents both of these features which give it a competitive advantage, especially considering its uniqueness confirmed by the establishment of the Nature Park. Using the traditional fishing and related skills – still practiced and remembered by the locals – as well as tangible cultural properties in tourism would ensure its sustainable cultural and socio-economic development. It is to be hoped that traditional fishing in the territory of Kopački Rit and Baranja will soon enjoy the status of intangible cultural heritage pursuant to the Act on the Protection and Preservation of Cultural Property (Official Gazette 1999/69). Registering the practice in the national list of representative intangible heritage would increase tourist attraction of the area but also enable a system of protective measures to effectively preserve this cultural value. Furthermore, residents shall be granted limited fishing rights in their cultural and natural environment, as this is the most effective way to ensure the continuation of this unique tradition.