1. INTRODUCTION

Good marketing is informative and equally useful for marketers and customers. It provides all relevant information necessary for an informed purchase decision and in the same time may not confuse, deceive and eventually mislead the customers. There are many ways to confuse and mislead the customers. The two basic principles are: 1) to withhold the important but not desirable or possibly harmful information or 2) to provide redundant, confusing and misleading information. Branding can be an important component of a business for several reasons: a) as an effective signpost for repeated purchases; b) as an entry barrier into the sector; and c) as a source of additional revenue. Good and effective brands, unregistered ones (™) or registered ones (©) are: a) easy to read, spell, pronounce and remember in all relevant languages; b) without adverse meaning in slang or undesirable connotations (in original and relevant foreign languages); and adaptable to all advertising media (Štefanić, 2015) . Labels have a very important role in marketing communication. They deliver a considerable part of the intended message together with legally prescribed information.

There is empirical and theoretical research supporting the claim that food labels impact on the consumers’ trust in food producers, processors and distributors. However, consumer and regulators interpret food labels differently, and labels can still be perceived as misleading by consumers. (Tonkin et al., 2016) .

Pinna et al. (2017) have found significant influence of customers’ gender, age, income level and occupation on their willingness to pay a premium price for labelled products. Empirical evidence on the critical role that quality labels play in influencing consumers’ choices and on the main motivation that hinders further development of this market was found.

Consumers interested in nutrition labels have specific dietary habits and are interested in food safety. They also use experts as their source of information. Purchases of the consumers concerned about nutrition claims are driven by factors such as price, brand, certification, etc. Socio-demographic characteristics are statistically significant and show a positive link with age, gender and a negative linkage with income (Stranierri et al., 2010) .

The study of Bialkova et al. (2016) investigates the health-pleasure trade-off and its effect on consumers’ choice in the EU. One third of the products carried health benefit claims, one third taste benefit claim, and one third no additional claim FOP. Finally, half of the products in the survey carried a nutrition label in front of the package – FOP. The results show that the message displayed FOP influenced consumers evaluation and choice. The effectiveness of the FOP message also depended on consumers’ health motivation and healthfulness perception of carrier products.

Nutritional claims are a commonly used marketing practice, but the association between claims and nutritional quality of products is unknown. Research of Taillie et al. (2017) investigated whether nutritional claims are associated with an improved nutritional profile, and whether the proportion of purchases with claims differs by race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status. They investigated low-fat, low-calorie, low-sugar and low-sodium claims in more than 80 million food and beverage purchases of 40,000 US households from 2008 to 2012. The association between investigated claims and specific nutrient densities varied considerably. Purchases of products with low-content claim did not necessarily offer better overall nutritional profiles or better profiles for the claimed nutrient, relative to products without claims. Results suggest that claims could be sensitive to certain foods or nutrients and, in some cases, may mislead about the overall nutritional quality of the food.

Orquin and Scholderer (2015) investigated the influence of nutrition and health claims used in marketing communication on consumer perception of food healthfulness. The results indicate that claims had little effect on consumer perception of food healthfulness. However, such claims had detrimental effects on sensory expectations and purchase intentions for the carrier products. The results of Poelmans and Rousseau (2017) are in line with previous research that stated that consumers are unwilling to pay high price premiums for organic vice products, such as beer. Additionally, no statistically different preferences for male or female respondents, or for members or non-members of nature protection organizations were found.

Trustworthy eco-labels provide consumers with valuable information on environmentally friendly products and thus promote green consumerism. Sonderskov and Daugbjerg (2011) investigated consumer confidence in different organic food labeling regimes with different degrees of governmental involvement in the US, United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden. The results indicate that confidence is highest in countries with substantial state involvement, implying that governments can positively influence organic agriculture through active and significant involvement in eco-certification.

The report by Hurt (2002) clearly indicates that “EU framework labelling legislation prohibits ‘attributing to any foodstuff the property of preventing, treating or curing a human disease or referring to such properties”.

Food allergy is a significant public health issue. Since there has been no cure for food allergy so far, regulatory bodies have focused on providing information about the presence of food allergens through label declarations. However, not all allergens could be declared, so different governments and organizations focused on “priority allergens” only. The increasing volume of the global food trade suggests that there would be value in supporting sensitive consumers by harmonizing these regulatory frameworks (Gendel, 2012) .

Precautionary allergen labelling (PAL) can result in consumer confusion. Research has shown that interpretive labels (using graphics, symbols, or colors) are better understood than the traditional forms of labels. It is important to investigate how consumers would use interpretive labels (symbol, mobile phone application and a toll-free number) with or without medical advice prior to the implementation into the food industry (Zurzolo et al., 2017) .

Food allergies affect up to 8% of children in the United States. Consumers rely on food manufacturers to reliably track and declare the presence of food allergens in products. The objective of the study by Gupta et al. (2017) was to characterize the factors that contribute to the economic impact of food allergen control practices in the food industry. Based on a survey conducted with food industry professionals, the key areas of cost for food allergen management were investigated. Nearly all companies (92%) produced food products containing one or more of the top eight allergenic foods recognized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or sesame seeds. Cleaning procedures, employee training, and the potential for a recall due to allergen cross-contact were most frequently rated as the important factors in food allergen management. Recalls due to food allergen cross-contact, cleaning procedures, equipment and premises design, and employee training were ranked as the greatest allergen management expenses. Although 96% of companies had a food allergen control plan in place, nearly half (42%) had at least one food allergen related recall within the past 5 years.

Quinones et al. (2017) compared two cases, Sorana bean Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) in Italy and Perry from Mostviertel PGI in Austria. Their conclusion indicates that supportive legal framework with assistance from public authorities can help producers in technical aspects, but also in resolving difficult conflicts. They also established positive relationship between the intensity and effectiveness of collective action and the likelihood of achieving broadly accepted standards and social cohesion needed for successful GI implementation.

Proof of niche market requirements, such as various ECO / ORGANIC seals are also very important for niche market customers. Kaur et al. (2016) based on a sample of 2034 foods established that foods carrying health related claims have marginally better nutrition profiles than those that do not carry claims.

EU Regulation No 1169/2011 is effective as of 13 December 2014. The new set of rules aims to improve the previous legal framework, allowing consumers to make more informed choices and a safe use of food products. Velardo (2015) emphasizes five main improvements defined by the Regulation: a) mandatory nutrition information on processed foods; b) mandatory origin labelling of unprocessed meat from pigs, sheep, goats and poultry; c) highlighting allergens in the list of ingredients; d) minimum size of text; and e) requirements on information on allergens (also non pre-packed foods) including those sold in restaurants and cafes.

It is well-established that food labels have an important influence on consumer behavior. But it is important to know what all those food labels actually mean. For example, official post-mortem meat inspection of pigs was replaced by visual meat inspection. The official veterinarian decides on eventual post-mortem inspection procedures (such as incisions and palpations) based on declarations in the food chain information (FCI), ante-mortem inspection and post-mortem inspection. It is clear that certain concessions are made in favor of a smooth slaughter and inspection process (Felin et al., 2016) .

2. METHODOLOGY

Analysis of food labels is a multidisciplinary and complex analysis, but food and packaging laws and control mechanisms are of primary importance. But intellectual property laws are also relevant in many cases. Finally, several laws regulating competition on the market are also significant, especially those ones regulating unfair competition (not covered in the analysis).

After a comprehensive literature review in the Introduction section, a comprehensive search of regulatory framework of food production, processing and distribution is conducted at the Croatian and EU level. Appropriate emphasis is given to the food related legislation and intellectual property related legislation.

Based on the analyzed data sources, published research results and legal documents related to the field of investigation, the results are organized in four separate sections: 1) mandatory food information; 2) voluntary food information; and 3) redundant, confusing and misleading information and 4) real life cases introduced to support the discussion.

Special attention is given to the definition of (safe) human food; declaration of nutritional characteristics, substances or products causing allergies or intolerances; geographical indication and origin of the food; quality seals; niche market claims (medicinal claims, organic food claims, and functional food clams); useful elements of the labels designed to facilitate purchase process and redundant, confusing and misleading signs.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Codex Alimentarius is a collection of standards, guidelines and codes of practice established to protect consumer health and promote fair practices in food trade at the global level. The Codex provides guidance on general labelling of foods and guidance regarding health or nutrient claims so consumers can understand what they are actually buying. The Codex Committee on Nutrition and Foods for Special Dietary uses (CCNFSDU) addresses a wide range of technical and regulatory issues for foods that can contribute to the prevention of nutritional deficiencies and diet-related non-communicable diseases. The Codex Committee on Food Labelling (CCFL) sets standards and guidelines for nutrition information on food packages enabling consumers to make informed food choices (Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme, 1985).

Croatian market regulation is fully reconciled with the EU Acquis communautaire. However, Croatian food producers have to pay attention to numerous regulations in different countries outside the EU. A variety of different signs and seals provide a lot of information but could possibly introduce some confusion and possibly some wrong purchase decisions (Figure 1).

Source: © Ivan Štefanić

The first step in the analysis is to define what can be actually promoted and sold as human food. Article 14 (2) (a) of Regulation (EC) 178/2002 incorporated into Croatian Food Law (NN 81/2013, updated text) defines foods harmful to human health as a food that is health defective because: does not meet the microbiological criteria for food safety under special microbiological regulations criteria for food; contains other pathogenic microorganisms, non-pathogenic and parasitic microorganisms for which estimation risk identified risk for human health; there is an evidence that people are poisoned by the food; contains contaminants exceeding the maximum permitted quantities prescribed by special regulations; contains nutritional additives and flavorings which are unauthorized in a given category of food or are permitted but exceeding the maximum permitted quantities prescribed by special regulations; contains unauthorized other substances according to a special regulation; contains pesticides in the amount presenting a risk to human health as established by the risk assessment; is genetically modified or contains and/or consists of or is derived from an unapproved genetic modification of the unapproved organism; contains ingredients of unapproved new food as determined by risk assessment and the risk assessment for a particular food has been found to have or may have a detrimental impact on human health.

Article 14 (2) (b) of Regulation (EC) 178/2002 incorporated into Croatian Food Law (NN 81/2013) defines food unsuitable for human nutrition due to the following reasons: if the best before date has expired; because of its changed properties (taste, smell, fading and decomposition) is not acceptable for human consumption; which contains foreign substances that can be reasonably suspected of being present in the rest of the series; in which production food additives are used, which do not meet the criteria of purity; containing permissible other substances above the permissible quantity according to a special regulation; which is packed in packaging that has been shown to be improper in health because it releases substances that are harmful for human health; which contains unauthorized chemical forms of vitamins and minerals according to a special regulation; which contains certain vitamins and minerals in an amount representing a risk to human health; which is subjected to unauthorized ionizing radiation or other technological process which may have harmful effects on human health; which is labeled as a food for special nutritional needs and does not meet such requirements; which is labeled as gluten-free food and contains gluten in an amount exceeding the allowable quantity according to the special regulation; which contains allergens not marked by a special regulation; GM foods containing and / or consisting of or derived from approved genetically modified organisms in which it has been shown to have a technological contamination above 0.9%, which is not indicated.

3. 1 Mandatory food information

There are two groups of information which are mandatory elements of food labels, a) label elements 3 defined by Article 9 and elements of nutrition declaration 4 defined by Article 30 of Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 . According to the same Regulation, the list of ingredients will include all the ingredients of the food, in descending order of weight, as recorded at the time of their use in the manufacture of the food.

Regulation also prescribes the size of fonts used in food declarations with the minimal size of the letters 1,2 mm, which is font of 3,42 points. For packages with the largest surface of less than 10 cm2, font can be equal or bigger than 0,9 mm (2,57 points).

Declaration of substances or products causing allergies or intolerances

Allergies represent possible life threatening situations for some consumers. However, only allergens listed in Appendix II of Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 are to be declared 5 . Article 21 of the same Regulation request that name of the substance or product causing allergies or intolerances shall be emphasized through a typeset that clearly distinguishes it from the rest of the list of ingredients, for example by means of the font, style or background color. In the absence of a list of ingredients, the indication of the particulars referred to in point shall comprise the word ‘contains’ followed by the name of the substance or product as listed in Annex II. Where several ingredients or processing aids of a food originate from a single substance or product listed in Annex II, the labelling shall make it clear for each ingredient or processing aid concerned.

Geographical indication and designations of origin for agricultural products and food products

A geographical indication is a distinctive sign used to identify a product as originating in the territory of a particular country, region or locality where its quality, reputation or other characteristic is linked to its geographical origin. The protection of geographical indications matters economically. They can support rural development and promote new job opportunities in production, processing and other related services. Over the years products such as Cognac, Roquefort cheese, Parmigiano Reggiano got excellent reputation far beyond the EU. The registration of Geographical Indications in the EU requires collective action and considerable efforts born by several groups of actors such as producers, processors, public authorities and research centers. Procedures related to protected designations of origin, protected geographical indications and traditional specialities guaranteed are defined by Regulation (EU) no 1151/2012 of the European parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

3. 2 Voluntary food information or useful marketing communication

Food information provided on a voluntary basis is regulated with Chapter IV of the Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 and shall comply with the following requirements: a) it shall not mislead the consumer (as defined in article 7); b) shall not be ambiguous or confusing for the consumer; and c) shall be based on the relevant scientific data (wherever appropriate).

Article 30 of the Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 also defines the voluntary nutrition declaration such as: a) mono-unsaturates; b) polyunsaturates; c) polyols; d) starch; e) fibre; and any of the vitamins present in significant amounts as defined in Annex XIII.

Annex III of the same Regulation defines six type of categories of food for which the labelling must include one or more additional particulars: 1) Foods packaged in certain gases; 2) Foods containing sweeteners; 3) Foods containing glycyrrhizinic acid or its ammonium salt; 4) Beverage with high caffeine content or foods with added caffeine; 5) Foods with added phytosterols, phytosterol esters, phytostanols or phytostanol esters; and 6) Frozen meat, frozen meat preparations and frozen unprocessed fishery products.

Additionally, Article 43 of the same Regulation additionally defines reference intakes for specific population groups as a voluntary content of the food label.

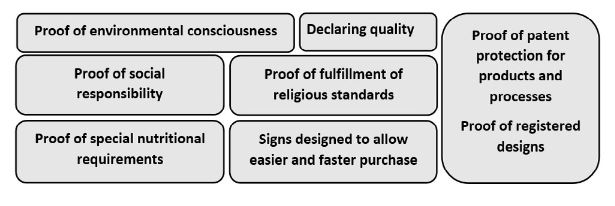

Figure 2 is presenting different categories of voluntary food information which can be used as effective elements of a marketing plan. In real life, it is difficult to be informed about all those possibilities and their rapid changes. Continuous education and cooperation with experts from various fields are important prerequisites to avoid costly mistakes and unethical ways of doing business.

Proof of uniform quality with ISO, EMAS, GAP, GMP and HACCAP certificates is a very important piece of information for the purchase decision making process. According to the Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 , food information shall not attribute to any food the property of preventing, treating or curing a human disease, nor refer to such properties. The regulation of nutrition and health claims made on foods is ,to a large extent, based on the belief that consumers are easily misled by persuasive marketing communication and should therefore be protected. From all the food producers, probably the producers of functional food and producers of traditional food are the most likely to be tempted to use medicinal claims in their marketing and they have to pay special caution in that regard.

There is a whole group of very useful information to the customers and competitors which can and usually does find its place on the food packaging. Those pieces of information are related to the patented products and processes, registered designs of the food packaging and signs designed to allow easier and faster purchase such as GS1 and PLU codes 6 .

3. 3 Redundant, confusing and misleading marketing communication

Producers can advertise their pasta containing wheat gluten as a ‘Protein pasta’ or ‘Durum pasta’. But without declaring content of gluten and its origin, they could possibly put the uninformed customer into a life threatening situation. Producers can also declare technological additives with the help of E-numbers or other less known synonyms, derivatives or various brand names instead of generic names. Use of phrase ‘natural ingredients’, use of pictures with ‘happy animals’ and pastoral landscapes in cases where they are not relevant and use of quality seals for merely complying with the legally prescribed minimum also belong to the misleading marketing communication.

An important question in the analysis of food labels are jurisdictions. Food laws and appropriate institutions and control mechanisms are the primary address. But intellectual property laws are also relevant in many cases. It is possible to check geographical indication or origin in the EU Database Of Origin & Registration (DOOR database, 2017) . To get quality advice, it is not enough to consult only food agencies, it is advisable to consult the relevant brochure European IPR Helpdesk Fact Sheet (2016) or IP specialist or Network of regional partners of Enterprise Europe Network and European IPR Helpdesk’s Ambassador Scheme provide free-of-charge, first-line information on IPrelated issues targeting the beneficiaries of EU-funded projects and EU SMEs in managing their IP assets.

3. 4 Case studies

Entrepreneurs could use registered or unregistered trademarks which can produce the impression that particular products are produced in certain territories, although they are not (Figure 2, 3, 4).

A photograph taken by Ivan Štefanić

Source: Author

Source: Author

For all those products (Figure 3, 4, 5), it is difficult to make an informed purchase decision even after a careful reading of the label.

Pumpkin seeds sold in the packaging containing verbal element California (Figure 3) could easily mislead possible buyers regarding the geographical origin of the product. Possible customers could be influenced by the very positive image of Californian producers of high quality produce like almonds, walnuts and pistachios and due to that fact they would make a purchase of a very different product originating from a very different territory.

Sheep cheese (Figure 4) could, in theory, be produced from the milk coming from Bulgarian and Macedonian farms (from FYROM or Greece) and then simply blended during the production process. But it is highly unlikely that message from the label is trying to communicate that information to the customers. However, two verbal elements used on the label (Macedonia and Bulgaria) can easily produce the impression of a sign of geographical indication, although they are not. Additionally, Bulgaria currently has no province or NUTS region named Macedonia. Also, there are three administrative regions of Greece with Macedonia in their names (Western Macedonia, Central Macedonia and Eastern Macedonia and Thrace) and Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia as an independent and internationally recognized state.

It is clear that oil from one bottle can be a blend of oils originating from Croatia and Spain (Figure 5). But labelling in such a case will be a different one; according to Article 4, Point 2 (b) (ii) of the Commission Implementing Regulation 29/2012 it will be stated: ‘blend of olive oils of European Union origin’ or reference to the Union. Additionally, information about territory where the olives were harvested and oil extracted should be stated on the packaging or labels attached to the packaging to ensure that consumers are not misled and the market in olive oil is not disturbed (Point 8 of the preamble).

4. CONCLUSION

Legal obligations regarding mandatory food labelling are limited in terms of information. Voluntary food labelling can offer a large array of additional information, but it is still regulated in a very precise manner.

Good marketing is informative and equally useful for sellers and customers. It provides all the relevant information necessary for informed purchase decisions and, at the same time, may not confuse, deceive and eventually mislead the customers. The labels have a very important role in that communication. Marketing communication, regarding their own brands, is an important component of the business for several reasons: A) as an effective signpost for repeated purchases; B) as an entry barrier into the sector, C) as a source of additional revenue.

The information provided on the food packaging usually exceeds the legally required amount of information and could lead to customer confusion and misinformation. An important issue in the analysis of food labels is jurisdiction. Food laws, appropriate institutions and control mechanisms are primary to be addressed, but intellectual property laws are also relevant in many cases.

Voluntary food information can be used as an effective element of a marketing plan. In real life, it is difficult to be informed about all those possibilities and their rapid changes. Continuous education and cooperation with the experts from various fields are important prerequisites to avoid costly mistakes and run a socially responsible business.