INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic is considered a global health and economic crisis[1]. It hit the world in March 2020 and imposed strict measures on the lives of the whole population, so the unprecedented circumstances affected everybody’s both personal and professional wellbeing. In the business context, it meant that ‘the new normal’ called for drastic changes in the way companies were operating. As it has disrupted many facets of people’s lives, it has also necessitated profound changes in the way work is done. Organizations around the world have had to suspend and modify their operations, which has led to major work adjustments and, even worse, loss of employment for numerous workers[2]. Physical distancing and not meeting with people due to measures imposed by the Government and, on a global level, by the World Health Organization, forced the companies to close their premises and move their work online. This dramatically changed the working conditions and everyday work routine, since physical face-to-face meetings, which were the best communication model that ensured immediate feedback, were not an option anymore and had to be replaced with remote work. To protect their own employees’ lives, and to stop the spread of the virus, or, at least, to contain it, the companies had to project their work in line with methods that secured the best possible communication flow and information exchange. Virtual platforms were the only tool the companies could use to meet with their colleagues, discuss their everyday activities, plan their business, target their clients, present their products, offer their services, and negotiate prices. As far as communication within a company was concerned, leaders had to learn how to effectively communicate with their employees and to successfully share their leadership knowledge and philosophy so that they yield desired results – something that in normal, non-pandemic circumstances they would have done in physical face to face meetings.

Generally, and within an organization, communication consists of complex, creative processes where the content is constructed and created through the interaction between individuals[3]. Researching Italian companies, Mazzei and Ravazzani found out that a “stream of unambiguous messages resulted in attitudes of realism and trust among the employees”[4]. Frandsen and Johansen[5] show that leaders in organizations must be aware of the importance of horizontal communication and give employees time to interact and thereby create meaning. Speaking of epidemic emergencies, Qiu et al. demonstrated how an open attitude and active engagement of stakeholders to address risk information needs can build trust and facilitate collaborations[6].

Emergency response situations, such as a pandemic, are highly complex and volatile and involve competing priorities and conflicting interests amongst stakeholders, so collaborative plannifng and shared decision-making is essential[7]. In the case with coronavirus, when a new norm was established - social distancing, which was wrongly named as what was meant was physical distancing – communication had to be founded on new pillars. Electronic means of communication became the only new reality, so digital technologies were adopted to enhance emergency management[8]. Hence, a virtual work environment became an everyday practice, characterized by work arrangements where employees are dispersed in various ways (e.g. geographically) and interact within and outside their company through technology[9].

But, to effectively run an organization and ensure good communication and quality collaboration, especially in a pandemic, it is important to understand what role leaders play in times of crisis, and what aspects of leadership are associated with success. This is particularly evident in a crisis or uncertainty, as people look to the statements, decisions, and actions of various leaders and attempt to discern which set of characteristics is best for addressing the problem at hand. So, since leaders are navigating the team and orchestrating the entire organizational process, much of the current theory and research has been concentrated on the vital part that they play in leading the company. What they suggest is that leaders are most effective when they can display an outwardly charismatic or transformational style[10]. Everything functions perfectly or, at least, well in times of normalcy but when familiar organizational structures and systems are lost, followers look to their leader for a sense of stability. In such scenarios, leaders with foresight, who were decisive and solutions-oriented, were seen as able to show a way forward[2]. Quick and timely action is the core of effective management since time is not a leader’s friend. The longer the crisis, the more likely the organization will be associated with trouble, so the leader should deliver rapid, honest, and transparent communication, which is the lifeblood of successful crisis management[11]. Oftentimes, employees can lack clarity in their tasks and the means of accomplishing them, and therefore leaders should step in to manage the virtual team because they know the goals, resources, and processes of the entire team best[12].

Our study strives to research the impact that the current crisis has had on a company’s internal communication by investigating four hypotheses. Namely, we make the following presumptions: (i) leaders have a different model of communication and frequency before and after the crisis; (ii) meetings duration different before and after the crisis is different; (iii) the crisis changed the preferred way of communication among the organization members; (iv) organization members’ preferred way of communication does not match with the leaders’ preferred way of communication. As far as methodology is concerned, two separate questionnaires (one for leaders and one for employees/organization members) designed by this study’s authors were used to survey these two hierarchical levels on the perceptions the leaders had on their ways of communication with their employees before and after the crisis, and how the organization members viewed the communication within their company. Most of the questions are asked to evaluate their leader’s style in these two periods – before and after the pandemic outbreak.

The article’s contribution is to understand the leader’s role in orchestrating the team in a pandemic, and for the successful running of the company, to recognize the importance of communication between the leader and the organization members. It is the common sense of identity and purpose that emotionally glues any group or culture, so great leaders need to ruthlessly protect their people; encourage connection, collaboration, and collective ownership; thus, nurture a safe environment of trust. In times of crisis, ensuring connection, collaboration, and communication is needed more than ever[13]. The leader should try to find a solution to the crisis, consider the financial stability of the organization, but also care for the welfare of the employees, by clearly presenting to them the company’s vision, role modeling behaviors, and making their followers feel like they belong[14]. To find answers to how (much) communication has changed in one company before and after the pandemic outbreak due to the COVID-19 crisis, our research instrument encompasses questions regarding the preferred ways of communication practiced in the two surveyed periods, as well as items connected with the group decision-making process and the role model leadership.

The article is organized into four sections. After the Introduction, the Literature Review part discusses internal communication and how leadership and internal communication are connected. This is followed by the Methodology part that is divided into a research instrument, and data and statistical methods. The Results section gives the leaders’ attitudes, the organization members’ attitudes, with a separate part on their comparison. Finally, the Conclusion discusses our hypotheses by outlining the research findings, followed by the practical implications of our study, the limitations, and future research possibilities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

INTERNAL COMMUNICATION

Various scholars like Dance[15], Losee[16], and Nilsen[17] agree on different approaches to understanding the definition of the word “communication”. Jones and George[18] portray communication as sharing of information between two or more individuals or groups to reach a common understanding. The intense global economic and technological development, the demographic shifts, and the migration of the workforce all have a massive impact on the dynamic environmental settings that organizations must have continually identified, modified, and aligned. In the context of the evolving environment, the stability of the principles of organizational functionality is relative, such as the culture, the vision, the leadership, and the communication[19]. In such circumstances, the degree of success highly depends on the power of the organizational system to effectively maintain the workforce.

The principles of management force the organizational systems towards communicating to secure the productivity of the employees within the organizational system. As information is the force that drives every organization and a foundation on which every company is based and moved forward, the main goal of the organization should be to convert information into doable tasks through a decision-making process. That is why the management of the organization acts as an information system[20]. Information systems are a communicative network knit between the so-called communicative points connected with two-ways communication channels, securing all necessary information for the user, at all times, at the lowest possible costs. In other words, a fully functional system consisted of employees, methods, communication techniques, and devices that enable the distribution of information (hierarchically, upward and downward) to all relevant communication points and decision-making centers.

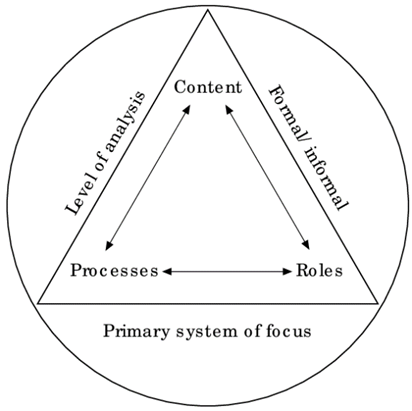

De Vries, Bakker-Pieper, and Oostenveld[21] consider leadership from a communicative perspective, and therefore they define the leader’s communication style as: “a distinctive set of interpersonal communicative behaviors geared toward the optimization of hierarchical relationships to reach a certain group or individual goals”. According to Church’s model of organizational communication developed as the C-P-R model[19], three components are highlighted as essential for the nature of the process: content, process, and roles. This model portrays the internal organizational communication, organizational culture, internal relationships, and models of teamwork. According to the author of the model, the content of information is the essence of the organizational culture, the beliefs, norms, and values that people hold about the company. The second component of the C-P-R model is a process that refers to the mechanisms, methods, and patterns of interaction to which the actual content is transferred or implemented from one subsystem to another. In other words, it is a form by which messages or information are shared among people, through face-to-face contact, emails, meeting, voicemail, and digital meetings.

The process can have two dimensions: informal and formal. The informal dimension consists of mechanisms such as performance appraisals, meetings, social networks and contracts, politics, rewards systems, and policies and procedures. Regarding the informal dimensions, Jones and George[18] state that first and foremost, no matter how electronically-based, communication is a human endeavor and involves individuals and groups, upon whose involvement the whole communication process relies. Church[19] maintains that the third component of the C-P-R model, the roles that the individuals have, helps identify exactly who is accountable for or involved in the various processes.

When it comes to establishing communication in a company, Bojadjiev[23], in his webinar, recommends eight principles for sustaining culture through communication in times of crisis, and those are: being consistent, leading from the heart, being passionate, leading by example, caring about the followers, building trust and followers, being brave and taking risks, and having open and effective communication. Regarding the last principle, ensuring open and effective communication, he suggests the model of organizational communication that is based on the Aristotle Rhetorical Triangle (ethos, pathos, logos), which stands for short emotional appeal, backed by facts and personal credibility.

When it comes to reaching a competitive advantage in the market, the increasing demand and impulse of the organization require managers to increase the efficiency of organizational communication. According to the principles of contemporary management in Jones and George[18], the four pillars of competitive advantage (efficiency, quality, responsiveness to customers, innovation) are based on a good organizational communication model.

LEADERSHIP AND INTERNAL COMMUNICATION

Barnard[24] comes up with specific rules to help executives create a system of communication within their organizations, and those are: the channels of communication should be definite; everyone should know the channels of communication; everyone should have access to the formal channels of communication; lines of communication should be as short and as direct as possible; competence of persons serving as communication centers should be adequate; the line of communication should not be interrupted when the organization is functioning, and every communication should be authenticated. This strong correlation between executives and communication that Barnard makes is driven by his knowledge that a true leader cannot lead effectively if they only put themselves in the role of a leader but do not communicate as such.

Benne and Sheats[25] proved that different individuals take on different roles depending on the different groups they take part in, dividing the roles as prosocial; thus, positively affecting the group. As there is a high positive connection between leadership and intercommunication in a company, when combined together, better results, decision-making and improvement should be expected. Therefore, one’s leadership effectiveness is measured on the basis of how well they communicate and on the relationships they create with their followers. Many authors have noted that communication is central to leadership (Awamleh and Gardner[26]; Den Hartog and Verburg[27]; Frese et al.[28]; Kirkpatrick and Locke[29]; Riggio et al.[22]; Shamir et al.[30]; Spangler and House[31]; Towler[32]) but for one leader to establish good internal communication, that is, communication with their organization members, one of the main requirements is to have good interpersonal communication skills.

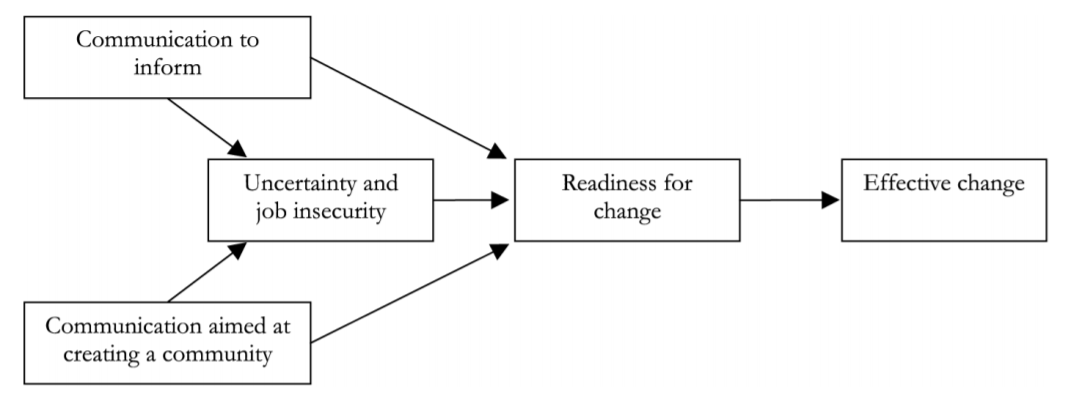

In times of crisis, the whole system of norms and values changes – the leadership style should be adapted to the communication and organizational changes that will inevitably follow. The change in communication and organizational change are two linked processes because the change in the organization is dependent on the ability to change the individual’s communication style. A change in the organization followed by no change in communication does not affect the long run and the future of that organization might be critical. For an organization to have an effective change, a clear definition of the change is required; for example: following the current situation, when a change is required during a crisis caused by a pandemic, the goal of the organization should be to change communication to less face-to-face interactive type, and more indirect contact. The change influenced by the environment can be easily endured and, hopefully, accepted if both communication and organizational processes are aligned. During a change, leaders must be supportive and coach their followers to keep them motivated, because for the change to be effective, only low levels of resistance are allowed. This means that the higher the level of resistance is, the harder it will be for the organization to adapt or implement a change. And, once the change has happened and needs to be announced, the change alongside goals must be passed on to the employees in due time and clearly, stating the reasons and the objectives the change aims for. The flow of information should be from the leaders as senders to the followers as receivers.

Changes take time and can cause uncertainty and job insecurity among the employees. In periods of change, the uncertainty of employees will have implications on employees as individuals, or on the environment when that employee is working. The employees are concerned with questions like “Will I still have a job after this change?”, “Will I still have the same co-workers after the change?”, and “Can I still do my tasks in the same way I used to?”, which are questions that mostly occur in periods of crisis, when layoffs are most frequent and people fear for losing their job or the future of their work place is questioned. To cope with the insecurity, leaders must share the knowledge, prepare their followers and keep them up to date, because if the employees know the motives for change, it will help reduce uncertainty and will hopefully create readiness that will eventually lead to an effective change, as shown in the following figure – Figure 2.

Every crisis creates negative emotions, distress, and feelings of uncertainty and, as the leader is the top figure in one company, it is important that he counters the negative course of action and proves to be in control of his life and those of his employees. The leader is the one to whom the others look for assurance and stability; therefore, his messages, regardless of the channel, should instill drive and motivation in subordinates, create readiness for change and motivate the employees to act.

COVID-19 is such a crisis; it has affected all aspects of our personal and work lives when organizational leaders must not only work through the economic challenges due to the crisis but also adapt their leadership to the current context. Yet, in the literature, leadership theories emphasize that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to leadership; instead, leaders must adapt their styles and behaviors to situational constraints and the needs of their followers. As Charles Darwin reminded us: “it’s not the strongest or most intelligent species that survive, but the one most responsive to change[13]”. Therefore, acknowledging people’s different personal circumstances and different responses to the crisis requires leaders to be attuned to employees not only a professional but at a personal level, too. Thus, for a company to thrive in a crisis, Kapucu and Ustun’s (2018) model of collaborative crisis management classified key crisis leadership attributes as traits and skills (decisiveness, flexibility, and communication), and as behaviors (problem-solving, managing innovation, and creativity, team building, planning, and organizing personnel, motivating, networking and partnering, decision-making, scanning the environment and strategic planning). As Perry and Laws[33] say, collaborative planning and shared decision-making are essential in emergency response situations that are highly complex and volatile and involve competing priorities and conflicting interests amongst stakeholders.

This again underscores that, among other things, the leader should assess the crisis or problem situation, should be flexible and understanding to the employees’ fears, needs and demands, rebuild the team’s strength, which is usually diminished in a crisis, solve problems, make decisions, motivate the followers, but most of all, communicate and network. And this communication part takes a huge ‘portion’ since it is vitally important for a leader to make connections with people at all levels of the institution during a crisis, as that makes the collaboration to be meaningful. Still, the specific nature of crisis moments, when a significant change is needed and there is a complete departure from norms, craves for communication to be absolutely meaningful because reliable information is scarce. In such cases, leaders must develop their point of view towards the situation and make sure that they communicate it to others in a way they will comprehend. This process, called sense-making by Maitlis and Christianson[34], works to establish a mutual understanding of a problem between leaders and followers that then allows for a cohesive and organized approach to problem-solving. In such times of turmoil, followers need someone to rely on, someone who can guide them through hard times, and that can be seen in communicating clearly what needs to be done to achieve a more positive result. That kind of leader will be surely endorsed by the followers. Getting followers to accept you and cooperate with you is a crucial part of leadership. For one leader it is very important to be liked, accepted, and supported to convey the messages successfully and accomplish their goals. A leader should motivate others to follow them and that is extremely important in turbulent times.

The importance of investigating the role of transformational leaders in shaping and facilitating processes in small firms is emphasized in the literature; first, because transformational leaders are known to demonstrate charisma, resonate with followers by presenting a vision, role modeling behaviors, and making their followers feel like they belong[34]. Also, the focus is on positive emotions framed through a vision for the future[35]. All this undoubtedly helps them to improve communication within the company and increase the quality and quantity of the information exchanged. Second, smaller firms are worth researching because they have a weak market and fewer resources compared to the big corporations, so the way they cope with the new challenges is insightful.

In the case of the coronavirus, leaders with guidance on using remote technology to foster engagement and emotional proximity in new virtual organizations are especially appreciated[36]. When Semaan and Mark[37] researched how technology could be used to make people resilient in maintaining their routines during extreme disruption, informants were asked how they conducted their daily lives before and during their respective conflict situations. Despite their inability to socialize in collocated settings, through the adoption and use of technological resources (e.g. the mobile phone, Instant Messenger and Facebook) their informants have reported that communication frequency has increased because it is now easier to connect with others. Surely, the new technological advancements such as e-mail, mobile phones, social media, etc., resulted in an even higher percentage of interacting compared to the one leaders had with their followers, let alone the new pandemic situation when electronic communication is not only recommended but imposed as the only possible means.

METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH INSTRUMENT

As a research instrument, the study uses two questionnaires, both of which aim at identifying communication between leaders and organization members in one company, when two periods are surveyed – before the pandemic outbreak (before 16th March) and after the pandemic outbreak (after 16th March). One questionnaire is filled in by leaders, who reveal their perception of their leadership behavior (both before and after the crisis), and another one is filled in by their employees, that is, organization members, who are asked to give their perception on and evaluate their leader’s leadership style, as well as describe their communication style with their co-workers.

The leader’s questionnaire consists of four sections. The first section covers demographic information about the leaders and asks about their age, gender, if they are a leader in their own company, the number of employees in the company, education, the length of their leadership position, and the company’s location. For most of these items, the respondents are offered multiple-choice options and are asked to choose the most appropriate answer, except for the last question, about the company’s location, when the respondents provide the country’s name. The second section asks the leaders to mark their preferred way of communication with their employees before and after 16 March, by offering them several items (face to face meetings, phone calls, email, Short Message Service (SMS)/Viber/Messenger, video conversation one-on-one or video conversation one-to-many and asking the leaders to mark these from 1 to 5, whereby 1 is the lowest rank and 5 is the highest. The third section shows how the group decision-making process changed in a pandemic in terms of meeting frequency, meeting duration, meeting structure, and communication of goals. For each category, several options are offered and the respondents reply by selecting the field that best answers the question. The fourth and last section displays how effectively leaders position themselves and how the organization members view them as role models through their leadership style by asking how much their engagement in getting the job done is a way to communicate their vision, to influence the organization members, how positive feedback is given, what kind of feedback is given when failing, what the most preferable decision-making style in the organization is, how much care is given to work-life balance, to the working conditions, as well as to rank the leader’s leadership style - leading from the heart, leading by example, and to evaluate the leader’s communication style: if it is based on credibility (ethos), on facts (logos), our emotions (pathos). When the question is given as a statement, the leaders are asked to rank their answers from 1 to 5; 1 meaning completely disagree and 5 – completely agree, while where several options are offered, the respondents should mark the field that best answers the question.

The organization member’s questionnaire consists of the same four sections as in the leader’s case, with the same marking procedure applied to each question. The only differences of this questionnaire are the following: In the first section, the organization members are asked about the length of their work experience in the company (not about the length of their leadership position); in the second section, they are asked to mark their preferred way of communication with their colleagues (unlike with their employees); in the third section, to mark how their leader communicates their goals (not how they do it); and in the fourth section, to mark their leader’s communication style (unlike their own).

DATA AND STATISTICAL METHODS

The study was conducted in a privately-owned company with a primary activity of betting on the game of chance. The questionnaires were administrated to two hierarchical levels: leaders and organization members, by distributing them to these groups both electronically and in hard copy, and giving the respondents an option to reply in a way more convenient to them. The total number of questionnaires filled in by leaders was 43 and by the organization members was 56. The survey was anonymous, and no signs that could reveal the respondent’s identity were made on the questionnaires. The information gathered for this study has been statistically analyzed by descriptive statistics, paired sample t-test, and independent sample t-test between means.

RESULTS

LEADERS’ ATTITUDES

The first questionnaire section, which gathered information about the demographic characteristics, showed that most of the leaders, 86%, were in the age group 30-50, 77% of the surveyed leaders were male, 91% worked in their own company, 58% of the leaders held a Bachelor degree, and the same percentage (58%) worked in their leader’s capacity between one and five years.

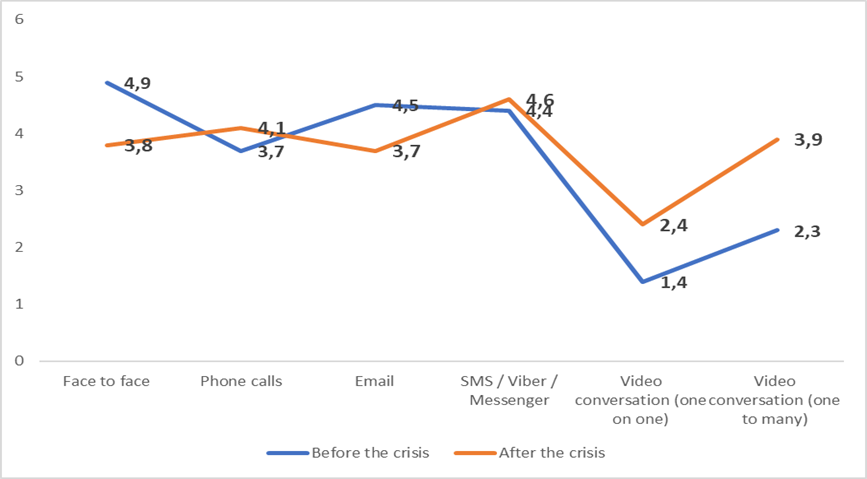

The second section, asking about the preferred communication model, showed that before the crisis, the leaders preferred to have face-to-face meetings, while after the crisis, their preferred way of communication switched to SMS, Viber, and Messenger as communication channels.

Before the crisis (before 16th March), leaders practiced more interactive types of direct communication. They were highly interested in face-to-face communication at the workplace while also using SMS after work. But after the start of the crisis, the focus changed: the leaders focused more on virtual-based interactions such as video conversation one-on-one, emails, face to face was still used, video conversation one-to-many, phone calls; but SMS, Viber, and Messenger had the highest percentage. It is noticeable that even though the company switched to virtual communication, the one-on-one type of communication had fallen off even on virtual platforms. This is because one-on-one virtual communication was not as effective as one-to-many types of communication where the leader addresses all issues, changes, plans, updates, and information to the whole group. Whereas conveying all of this in one-on-one form would take a lot more time, it still is a used way in cases when it is required to share some quick information with only one person. The results from the third section - about group decision-making within the company - are graphically presented in the following figure.

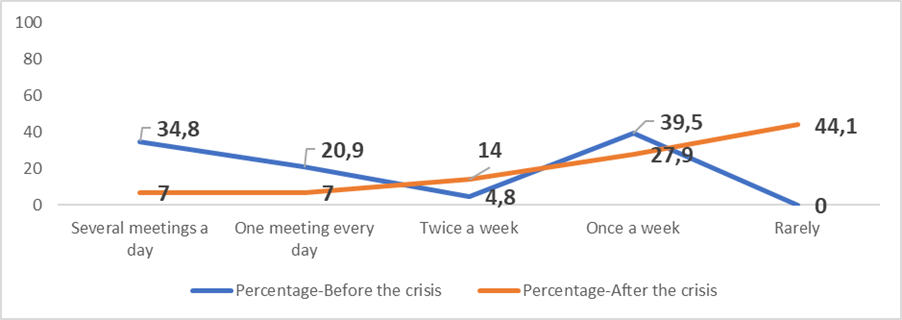

Namely, the first question from this section asks for the leader’s opinion about the frequency of their formally scheduled meetings before and after 16th March. Before the crisis, the most frequent meetings were those held once a week – 39,5 %, while after the crisis, meetings were rarely held, that is, the highest percentage – 44,1 % - in this category was given to the answer option ‘rarely’.

When asked about the most effective meeting duration, 60,5 % of the leaders maintained that shorter meetings (less than an hour) were more effective than longer ones. But surprisingly, this situation didn’t change after the crisis; on the contrary, the already high percentage of shorter meetings increased after the crisis, that is, even 90,7 % tended to practice shorter meetings after 16th March. Undoubtedly, this clearly shows the leaders’ preference for shorter meetings, which just escalates after the crisis.

The leaders’ ways of communicating their goals and vision to the employees have changed. Before the crisis, one-on-one meeting face to face had the highest percentage – 37,3 %, and after the crisis, this category – one-on-one face meeting still had the highest percentage of all ways of communication – 35,7 %, which is slightly lower than the percentage before the crisis because after the crisis email and phone conversation had higher values compared to the period before the pandemic outbreak. This proves that, once the pandemic had started, the leaders thought of safer ways of communicating, that is, they adapted to the situation by practicing more email, phone, and video conversation, which had lower use-value before 16th March, while maintaining the use of physical, face to face, one-on-one meeting.

Both before and after the crisis, the leaders preferred the participative decision-making style, which implies their consulting with the organization members. Their participation in the company’s decision-making processes marks a pretty high percentage of 86. The interesting fact proven by the statistical analysis is the fact that leaders did not change their preferable decision-making style since statistically there is no significant change in the preferable decision-making style before and after the start of the crisis.

When asked about their dedication to promoting a better work-life balance and working conditions, leading from the heart and leading by example, again the highest value is in the same category. Both before and after the crisis, the leaders thought that their leading was by example.

ORGANIZATION MEMBERS’ ATTITUDES

The first questionnaire section determined that 60,7 % of the organization members were in the age group 30-50, their gender distribution was equally divided – 50 % male and 50 % female, and on the education note, 59 % had a college degree, as shown in Graphs 7, 8, 9.

The second section questions the organization members’ preferred way of communication. Before the crisis, they preferred face to face meetings, while after 16th March, this mode of communication dropped to an astonishingly low level, whereas the use of all other forms of communication increased: video conversation one-to-many, video conversation one-on-one, SMS, Viber, and Messenger, email, but phone calls were reported as the most preferred communication mode among organization members.

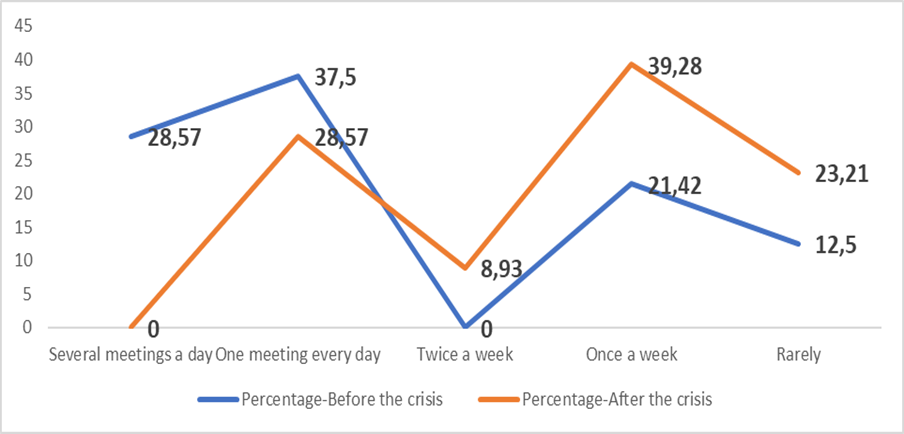

The third section titled Group decision-making surveys the organization members’ opinion on the frequency of the formally scheduled meetings with their colleagues. Before the crisis, the highest percentage of 37,5 % was given to one meeting every day, while after the crisis, 39,28 % was given to having meetings once a week. The following figure illustrates this:

Shorter meetings were more common before the crisis, with 60,71 %, and this category was still dominating after the crisis – 71,42 % claimed that shorter meetings were more effective than longer ones.

Both before and after the crisis, when communicating with their employees, leaders mark phone conversation as the best way to communicate their goals and vision. Before the crisis, the phone was used 28,22 %, with video conversation, regardless of whether one-on-one or one-to-many, not used at all, while after the pandemic outbreak, the use of phone increased to 38,46 %, video communicating one-to-many remained not to be used at all, but the video conversation one-on-one started to be used and had a percentage of 4,81 %.

According to their employees, the leaders’ involvement had not changed due to the pandemic; both before and after the crisis the leaders were involved by giving feedback.

The paired samples statistics for these categories show that before the crisis leaders paid equal attention to work-life balance, and their leading by example, while after the crisis, their priority was balancing between work and life.

COMPARISON

When comparing the leaders and organization members’ answers concerning the most preferred way of communication, Table 1 shows that when talking about the period before the pandemic outbreak the leaders and their employees’ answers overlapped; both groups claimed that in that period communication was dominantly face to face. However, their answers mismatched when asked about the way they most preferably applied after the pandemic outbreak, that is, the leaders maintained that in the pandemic they preferred SMS, Viber, Messenger, while the employees said that after 16th March phone calls were predominantly used.

**p ˂ 0,01; *p ˂ 0,05; 1 - being the lowest rank, 5 – being the highest

** p ˂ 0,01; 1-fully disagree; 5-fully agree

In Table 2, the comparison is made between the leader's and their employees’ answers regarding how leaders are involved in getting the job done. Both groups of respondents have said that, before the crisis and after the crisis, the leaders were present in doing the job by giving feedback. This shows that the leaders’ involvement before and after the crisis has not changed – their ‘giving feedback’ outnumbered ‘sharing vision’ and ‘influencing’.

Table 3 shows the leader’s dedication to four elements as part of their leadership model: whether they care for creating work-life balance, providing better working conditions (their followers’ physical and mental health, communicating with employees about what protocols the organization is putting in place to keep them safe), leading by example, or leading from the heart, and if this has changed in the two time periods - before and after the crisis. The leaders answered that before the crisis they had mostly led by example, while when the employees were asked about what their leaders were dedicated to in this same period, they gave the same values to ‘creating work-life balance’ and ‘leading by example’. Talking about the period after 16th March, the leaders insisted on leading by example, while their employees marked attention to work-life balance as a dominant element in their leaders’ philosophy after the pandemic outbreak.

*p ˂ 0,05; **p ˂ 0,01; 1-not implanted at all; 5-fully implemented

Table 4 shows linearity in the leaders' and organization members’ answers when asked how their leaders lead: by ethos, logos, and pathos. Both respondents’ groups maintained that in the period before the crisis and after the pandemic outbreak the leaders were leading by logos. The mean values of this category are dominantly higher compared to the other two categories.

*p ˂ 0,05; 1-not implemented at all; 5-fully implemented

CONCLUSION

In this article, out of the four research propositions that grounded our research, the findings from the questionnaires resulted in accepting half of the research propositions and rejecting the other half.

The first research preposition (RP1), which states that leaders have a different model of communication and frequency before and after the crisis, was accepted. The results have shown that leaders indeed have a different model of communication and frequency before and during the crisis, that is, the face-to-face meetings before the crisis were replaced by safer, virus-free communication channels like SMS, Viber, and Messenger, which is quite expected due to the health recommendations and the imposed measures. However, what is surprising is that the frequency of meetings category results was not aligned with the urgency of the situation, that is, one would expect meetings to be more frequently held after the start of the crisis when more directions and consultations are needed, but what the leaders said is that before the crisis they had meetings once a week, while after the crisis they rarely held meetings. This makes us conclude that the urgency of the situation and the uniqueness of the issues the leaders are facing required them not to have fewer meetings, but on the contrary, to use more informal, electronic, ways of communication rather than calling, even a virtual, meeting.

The second research proposition (RP2), suggesting that the leader’s meeting duration is different before and after the crisis, was rejected. Namely, the results have shown that both before the crisis and after the pandemic outbreak, our surveyed leaders preferred shorter meetings and even strengthened that tendency after 16th March. Again, the urgency of the situation and the lack of time must have led to short, straight-to-the-point meetings, but still, the meetings’ duration was not different in the two surveyed periods.

As far as the third research proposition (RP3) is concerned, which assumes that the crisis changed the preferred way of communication among the organization members, this is accepted. The research shows that the crisis did change the preferred way of communication among the organization members, as their usual face-to-face form of meetings before the crisis was replaced by virtual modes of communication after 16th March, with phone calls being most frequently used for communication with their coworkers.

And the last, fourth research proposition (RP4), which suggests that the organization members’ preferred way of communication does not match with the leaders’ preferred way of communication, is rejected. Both surveyed groups: leaders and organization members stated that before the crisis they communicated face to face, while after the pandemic outbreak their mode of communication was virtual: with SMS, Viber, and Messenger applications. This proves that the preferred way of communication of these hierarchical levels was the same, both before and after the pandemic outbreak.

Compared to previous studies[3, 4, 6, 19], this research confirms that communication is very important when leading a company in any normal circumstances, but it becomes even more important in extreme disruptions[37] or in times of a pandemic, when the ways of communication between the leader and organization members, and among the organization members themselves should be cleverly chosen, skillfully practiced and constantly monitored so that the wellbeing of the employees and that of the company are ensured. But, for one company to thrive in such unprecedented conditions, it is not only important to quickly adapt to the virtual forms of communication[8], but it is also the leader’s image and leadership style that matter a lot – the company’s successful functioning would be guaranteed if the leaders are prepared to give positive feedback, care for the work-life balance, pay attention to the working conditions and lead by example. Of course, collaborative planning and shared decision-making is essential[7], as it is clear presenting to the employees the company’s vision, role modeling behaviors, and making the followers feel like they belong[14].

The practical implication of this study is to give the companies’ leaders an insight into the perceptions that their organization members have of the type of communication that they have practiced before the crisis and after the pandemic outbreak and, according to that, help the leaders shape the way they communicate with their employees in the future. This research shows leaders how they are viewed by their employees and what can be changed in their leadership style and communication model not only in times of crisis but, generally, in their normal, business everyday communication. The results will offer the leaders a chance to self-critically look at their work and reflect on their way of doing business. They can certainly learn from the answers given to all questions, but it is the last section, role model leadership, that will inform them most about what needs to be changed, in terms of how they communicate their vision, how they influence their organization members, how they give positive feedback, how they react when an employee fails, to reflect on their decision-making style, reassess their attitude to work-life balance and the working conditions, as well as self-analyze their leadership and communication style.

The limitations of this research are that it is conducted at one company, and is related to only one sector. Further research could investigate the impact that the COVID-19 crisis has had on internal communication in several companies from this sector, and to be additionally expanded to companies from several different sectors. In addition, more countries with companies from several sectors can be included in the research to test our hypotheses on a multinational level and investigate the impact that this crisis has had on their companies’ internal communication.

Looking into the research itself, based on the C-P-R model of communication, for organization members, communicating the content is far more important than the form by which the information is delivered. This leads to the fact that the informal way of communication, due to the limitations caused by the virus relating to health issues, is a more applicable way of communication and the main way through which the organization members can receive the intended content and inform themselves. In practice, executives have to communicate quickly and clearly to be in front of potential issues rather than having to counter misinformation. Once found in lockdown, they had an extremely short time to adapt to the new, strange situation; to calm the employees; encourage them to go through the unknown together; support them in their work and show them that the leaders are always available to their organization members.