1. Introduction

The Age of Discovery was characterized by the need, as well as the challenge to create newer and more practical cartographic representations of the known world. Through explorations of the New World and its recently discovered continents, the interest of map users and makers started to shift more towards practical knowledge about their geographic characteristics and distances between certain areas than on ideological representations of the known world from the (mainly Christian) theological perspective, prevalent in medieval monastic cartography. In addition to cartographic and geographic information, the symbolism of early modern nautical charts in a smaller scale as well as of new maps of the known world was represented in specific decorative elements or iconographic peculiarities, stemming from the medieval tradition. Additionally, nautical charts from the beginning of the early modern period had additional qualities connected to their utilitarian function providing more precise navigation, such as better orientation possibilities represented by compass roses and rhumb lines.

The main goal of this paper is to evaluate iconographic communication possibilities of decorative visual elements and more complex symbols represented on the medieval and early modern maps and charts of the known world, including the nautical charts of the New World, with a special emphasis on the charts representing the territory of today's Croatia.[1] Along with the symbols in mathematical and orientational elements of the maps/charts, the representations of real and imagined territories depended on culturologically acceptable concepts of space. The authors have compared the visual elements and representations of spaces from maps and charts of different provenances (from Western European to Venetian and Ottoman) and functions in synchronic and diachronic perspectives, ranging from compass roses, representations of ships, religious imagery such as saints to ethnographic elements or fauna, to decipher their different, especially symbolic, meanings.

Researchers, including art historians, have so far given little attention to decorative content and visual symbolism on maps and charts, focusing mostly on the geographic and purely cartographic content, especially in the case of the maps of the Mediterranean basin. The aim of our comparison was to find similar communication patterns or collaborative practices even in the mutually opposite interests of different imperial cartographies. Those consisted of using the map as an argumentation or justification of economic pretensions, as well as an expression of cultural, religious or military interests, with cartographers thus becoming the creators of images of mapped spaces. In this aspect, the role of the division of power, more precisely the territorial jurisdictions and/or economic supremacy over a certain space was important. It is precisely this alternative role of communication possibilities of a map, along with its primary orientational and navigational function, that is the focus of this paper. On the one hand, the mode in which the visual content changed from the medieval to the early modern period on maps representing various spaces and within different cartographic traditions was also questioned, in view of both the utilitarian (navigational) functions of the chosen charts. On the other, the role of the map (or chart) as a communication device and historical testimony was investigated. Special emphasis was put, depending on the available sources, on the manner in which the territory of today's Croatia was represented (and to which degree this territory was familiar to different cartographers) on the medieval and early modern maps of the known world.

2. Methods, Sources and Approach

Through the methodological approach of comparative qualitative analysis of illustrations on the chosen maps and charts certain patterns of communication were identified − more precisely argumentation or even change in perception − of the known world in synchronic and diachronic perspectives. With such an interdisciplinary approach, following the recent historiographic paradigms such as “borderlands history” and integrativeness applied to early modern (or earlier) archival sources, and discursive approach of cultural cartography, neo-cartography and imagology, the use of chosen visual arts elements regarding the ideology, religion or cartographic tradition to which a particular map (or its author) belonged to was analysed. Thus, the map was viewed as a symbolical visual graphic or an image of a subjective geographic reality and a historical construct composed of visual and symbolic elements, that never loses its value of cultural representation (Harley and Woodward 1987, XVI, 506).

Among the chosen sources, the visual art elements on early modern portolan charts were analysed in more detail, whereas medieval mappae mundi served as a substrate to investigate the transformation (continuity and discontinuity) of the established visual symbolisms in different cartographic traditions.

The chosen sources come from different provenances and belong to different types and geographic discourse (approach to space). Even though they are not unknown in scientific literature (Škiljan 2006)[2], their artistic quality and multi-layered pictorial characteristics of information have never been more seriously elaborated. One part of this paper is thus aimed towards an iconographic analysis of medieval maps, such as the two largest and most prominent dating back to the 13th century – the mappa mundi from the monastery in Ebstorf (Die Ebstorfer Weltkarte, 1234) in Lower Saxony and the mappa mundi from the cathedral in Hereford (Hereford MappaMundi, 1300;Hereford Cathedral Map, 1300) in England. From the more recent, early modern period, the portolan and nautical charts, as well as world maps of European cartographic schools and Ottoman cartographic production were analysed, among which the best-known is certainly the impressive opus of Piri Reis.[3]

3. Theoretical and Terminological Framework of the Analysis of Images on Maps and Charts

The aesthetic component of cartography has evoked the interest of researchers relatively recently, being otherwise considered secondary in comparison to scientific and technological aspects of creating and using maps. The scientific tendency to deny the aesthetic value of maps and their potential to communicate, thus reducing them to a model of consistent use by following established rules without the personal, creative input of a cartographer, has diminished during the recent decades[4] (Karssen 1980: 121). Although the aesthetic value of a map was contained in the experience of beauty through the composition and arrangement of elements such as cartographic signs (including dots, lines, areal shapes, textures, colours), cartouches, compass roses, letters, drawings of animal and human characters as well as armorial bearings, it differed nevertheless from the decorativeness and subjectivity of other art forms in its partial rejection of abstract content and usage of non-standardized symbols. (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017, 24-25). While the search for precision in spatial representations certainly decreases the scope of artistic expression, the global trend of standardization in map production was of a later date. First signs of that process appeared in the well-known works of the Renaissance cartographers, caused by their subjective observations. However, it started to flourish in 18th century map production, which was based on previous land-surveys. One cannot deny the importance of formal aspects in aesthetic evaluation of maps, such as line, colour and composition, however, on older maps, especially the earliest ones, the iconographic interpretation of symbols and motives was equally important, surpassing even their aesthetic function. The iconographic method in this work was used to identify, classify and interpret the visual content on the chosen maps and charts in order to decipher their meaning and sense in social and historical context.[5] In this case the iconographic analysis of visual symbols on maps aids in clarifying the represented ideas or imagens about the Others/Otherness in analysed cartographic sources, or more precisely, of the conceptions of one's own space and the space of Others – the dichotomy that is equally important in medieval and early modern maps of different primary functions.

Namely, during the medieval and early modern period, the map is as a depiction of space, as well as an imaginarium, constructed from its author's personal interpretations or as an upgrade to the already known parts of transcribed geographic reality. It reflected, in part, his religious, ethnic and cultural identity, his vision or representation of space and consequently, political programmes and pretensions (Mlinarić and Gregurović 2011, 98). Those cartographic images of cultural representations of foreign lands were “burdened” with complicated ties of cultural positioning and power relations, even in choosing the information they contained, as well as a plethora of connotative meanings that were shaped by the author through his arrangement of information (Škiljan 2006;Dukić et al. 2009). Therefore, spaces and identities represented on maps were testimonies of spatial organization, as well as knowledge of newer geographic information, which could have carried different statuses of diversity and Otherness – from political allegiances, cultural, ethnic or religious affiliations, age, sex and economic status. To find elements of the author's subjectivity on maps demanded “reading between the lines” of the applied cartographic key, especially if one takes into account the contemporary abundance of discursive possibilities.[6] Within the mental conceptualization and reconstruction of space on western maps, the most prominent symbols were in the service of the worldview, i.e. the redefinition of human presence of Earth, as well as ideologies – religious (Christian or Muslim) and secular (social, related to the social stratification of the times, or political). (Mlinarić 2019, 366).

4. Communication Potential of Medieval Programmatic Maps of the Known World (mappae mundi) and Early Modern Nautical Charts

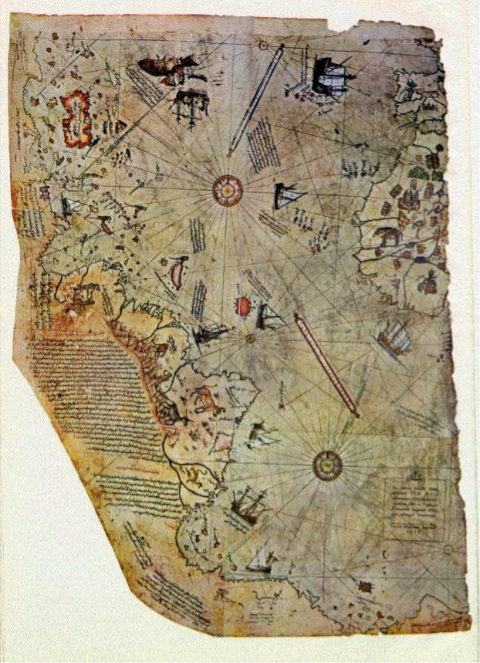

The mentioned types of old maps emitted various messages related to their function and available geographic knowledge. Medieval monastic mappae mundi, such as O or T-types, representing the three known continents of the Old World[7], such as the Hereford map (Fig. 1) were rich in symbols and functioned as a political and cultural education device, or, even more so, a programmatic compendium of (mostly Biblical) knowledge about the known world from a theological perspective. Although, like other maps, they are generic representations meant to aid in spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes or events (Harley and Woodward 1987, xvi), mappae mundi do not have the utilitarian function typical for maps of representing geographic space and spatial relations as truthfully as possible on a two-dimensional medium in order to simplify orientation and provide more complex insight into geographic features. To fulfil this role, they lack mathematical elements, such as cartographic projection and related coordinate lines and scale. Their focus was primarily on philosophical and religious principles and the didactic role of teaching the harmony of God's order and creation (Barber and Delano-Smith 2018, 117;Harley and Woodward 1987, 342). Although the specimens of larger dimensions exist, such as the Hereford map, most of the maps of this type are found in manuscripts. Therefore, their dimensions were small, and they were not detailed, which is why they are not especially informative in the geo-cartographical sense, especially when it comes to mapping land and coastlines (Edson 1997, 11). The Biblical scenes from Christian iconography were especially important, which is why the ideological authority justified such content until the Age of Discovery. After this period such maps could not fulfil the task, neither of practical use to sailors on transatlantic journeys, nor the challenge of exploring the New World. When examining the representations of Croatian lands on those earliest maps of the known world, the detail of the Adriatic (Fig. 1, detail) confirms their function. Mainly, the Adriatic Sea does not have a recognizable coastline, not even in contours, as its representation serves the ideological imaging of a much wider space, more precisely emphasizing the very important and over-dimensioned Rome in its vicinity, positioned near the centre (Roma caput mundi…).

Fig. 1. a. Mappa Mundi from the Hereford Cathedral, b. detail showing the Adriatic Sea, cca 1290 (Source:the Hereford Cathedral Mappa Mundi, 1300) / Slika 1. a. Mappa Mundi iz katedrale u Herefordu, b. isječak s prikazom Jadrana, oko 1290. (izvor:the Hereford Cathedral Mappa Mundi, 1300)

On a different note, the utilitarian[8] purpose of portolan or nautical charts as typical thematic charts is focused on the more precise geographic representation of coastlines and islands, especially the emphasized objects of terrestrial navigation with documented geographic names. The invention of print aided the re-discovery of the Antique diagrammed world systems and the renaissance of the Ptolemy's opus precisely in the period of the discovery of the New World, while transoceanic navigation demanded cartographic realism and more precise nautical charts (Barber and Delano-Smith 2018, 125). The mathematical and construction elements such as rhumb lines and coordinate lines were introduced in order to give as precise an image of the Earth's surface (in all of its segments) as possible, while the nautical charts themselves encompass, in a pictorial sense, the informative purpose of the nautical manuals. The complete purpose of a high-quality map is to make possible the determination of the geographical position and spatial relations among depicted geographical objects. Even though the Renaissance taste necessitated a richer aesthetic quality, and humanistic curiosity along with the commercial needs of pre-industrial society (ancien régime) the introduction of newer techniques, technologies and information on discovered lands, nautical charts became more concerned with the quality of geographic and spatial preciseness and informativity, putting aesthetics aside.

To conclude, the emphasis on pictorial decoration was inversely proportional to the need for precise geographic documentation of spatial relations. On the contrary, the discoveries commanded the need for visual synthesis of known geographic data, which was accomplished also by reworking and thorough revalorization of medieval mappae mundi. Complemented by the empirical knowledge of sailors, the medieval maps have evolved into more complex versions, or hybrids, of Antique maps and world maps still rooted in the Christian iconography (Škiljan 2006, 62).

5. Discussion: Using Cartographic Pictoriality to Communicate Specific Geo-cartographic Messages

Pictorial elements on maps and charts, such as compass roses, ship varieties, figures of saints, real or fantastic animals or terrestrial markers on land used for orientation in maritime navigation, can be correlated to analyse various layers of communication potential of a specific map.

Iconographic motives on medieval world maps (mappae mundi) are illustrations of a wide array of knowledge of their makers, positioned in a way that they thought sensible and that, from the point of view of semiotics, have many different meanings. The visual images on chosen mappae mundi can be grouped according to their textual base in Biblical and classical scenes – both the mythological and real sites mentioned in sources. The information came from various compendiums of medieval knowledge[9] based on the then available Antique sources (including Pliny and Herodotus). Not only did the medieval world maps construct the known world according to the medieval compendium of knowledge, but their role in shaping the identity and feelings of belonging was also very important[10], with a crucial dichotomy between Us and Them in its core, as attested by the positioning of various visual images within the known world.

However, an especially interesting aspect of the Hereford and Ebstrof mappae mundi, which were chosen for analysis as the most representative specimens of medieval monastic cartography, is the abundance of images of animals, real and fantastic, as well as various tribes and ethnicities of fictional characteristics that are almost all found in Pliny's Naturalis Historiae. They are mostly located on the edges of the known world, in Asia and, to a largest extent, in Africa. In the centre of the map, on the territory of the Christian world familiar to the cartographer, priority is given to the depictions of cities and concrete information about them. The peoples and ethnicities that live close to the ocean's edge and its islands are shown completely nude with emphasized fantastic attributes. Nevertheless, despite standardized content, certain images were sometimes in service of a completely different mode of cartographic communication, depending on the context. For example, the city of Jerusalem that on both maps occupies the central position; on the Hereford map it is depicted as a circular fortress with strong walls, while on the Ebstorf map its importance is additionally highlighted with the image of the resurrected Christ triumphally rising from his grave, dressed in white and holding a cross in his left hand. Also, on the Hereford map the Jewish people are depicted as being located close to the Red Sea (marked with the inscription Iudei), they are worshipping the idol Mahun and have emphasized facial features deemed characteristic for this population, demonstrating the author's stereotypical representation of Others.[11]

Among the fantastic animals, one can find unicorn, basilisk and griffin on both maps, as they are the most common animals of the medieval bestiaries. The number of real animals is greater on the Ebstorf map, while on the Hereford map one can also see the manticore, mandragora, sphynx, faun, satyrs etc. – repeating again the same model – the animals with the most fantastic characteristics are shown at the world's edges. Taking into account their primary function, one can notice that mappae mundi did strive to reflect the level of knowledge of their period, as seen in the lack of knowledge on coastlines.[12] Although the mysteriousness and exoticism of pictorial representations was a standard, it is clear that unicorns are found in places of (seemingly) unknown geographic content, substituted by imaginary and interesting creatures precisley for this reason, which was practiced both as cartographic concept and individual practice.

The process of map creation does not consist merely of constructing a geographic reality but also a construction of meaning (Duncan and Ley 1993, 331). The noticeable opposition between Us and Them in the case of both mappae mundi was already pointed out, the first being the dominant group to which the cartographer and his target audience belong, characterized primarily by their belonging to the Christian world, and the second group consisting of all who do not belong to the first, with precisely those characteristics that separate them being visually emphasized. The term “barbarians” that appears on the Hereford map, has been used since Antiquity to denote groups that are inferior by various characteristics, and it is used even today to mark Otherness. From the 12th to the 16th century in the collective conscience of the Christian West this term was used to mark people who are not Christians and who are acting in an “uncivilized” manner (Duncan 1993, 44). Within the category of Others, Staszak differentiates between the group he calls the Barbarians, characterized by the ability to integrate to a certain extent into the dominant group and the second group, the Savages, with monstrous and unnatural characteristics incompatible with civilized society, such as cannibalism, nudity or inability to speak. Furthermore, he emphasizes the spatial component of such Otherness – civilization radiates from one, central place (Jerusalem, a particular city, Europe…) and Savages inhabit its border zones (such as Australia) or interspaces (our forests) (Stazsak 2009, 44-47). If one applies this theory to medieval maps, civilization spreads from the physical centre of the map, Jerusalem, while on its edges the number of peoples of unusual or fantastic characteristics increases, whereas those that can be called Barbarians, following Staszak's categorization, can be found closer to the centre[13]. Such a pattern continues in the following centuries, but with the expansion of the oikumene, the perceptions of known and unknown lands change and consequently the categorizations of the Barbarians and Savages.

6. Iconography on Earliest Maps of The New World – Comparison of Two Different Traditions

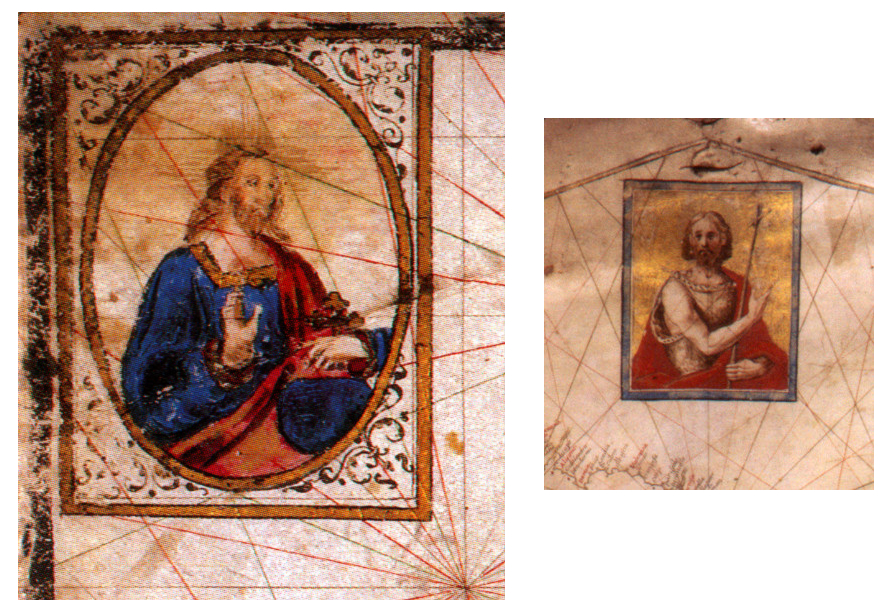

Immediately after Columbo's discovery of the New World, two maps were made that are very interesting for comparative analysis. The world map of Castilian navigator Juan de la Cosa (Juan de la Cosa, 1500) and the world map of Ottoman privateer and later admiral, Piri Reis (1513), although made in different traditions, both inherit the medieval visual symbolism in different ways, while introducing some new pictorial elements that will become standard during the later centuries.[14]

The map of Juan de la Cosa, with its “Western” representation of the Old World appropriates certain fantastic elements from the medieval mappae mundi, usual for the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa). The most evident is the image of Gog and Magog – the Biblical legend of the tribes that dwell behind the walls of their cities from which they will come out on Judgment Day. During the Middle Ages, this legend was expanded with a detail that Alexander the Great built those cities, and in this version they appeared on the medieval world maps. For example, on both the Ebstorf and Hereford maps Gog and Magog are located at the shores of the Caspian Sea – on the Ebstorf map they are marked with an illumination that shows walled-up peoples in actions of cannibalism (Die Ebstorfer Weltkarte, 1234), whereas on the Hereford map only Alexander's wall is depicted closing a mountain pass, and inside of it there is a long description of the various horrors that the place inhabited by evil sons of Cain holds.[15] In the case of Juan de la Cosa's map, inside of the walled-up space in which the said tribes live, the city is shown, flanked by one Cynocephalus and one Blemmy, the peoples that on medieval mappae mundi are usually shown on remote and unexplored places. On the map of de la Cosa the detail of the mythical Ethiopian king, Prester John, is also undeniably borrowed from the medieval tradition. Besides him, in Africa, Europe and Asia the many depictions of various rulers are shown who, depending on where they are located geographically, are dressed either in the western or Muslim tradition. They are contrasted by the images of the Blemmy and the Cynocephalus from the cities Gog and Magog, located on the edge of the known world, a place out of reach of civilization, where Savages dwell.

Unlike Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia that Juan de la Cosa marks with various illustrations, both secular and religious[16], the New World is shown as a land of infinite forests, without any symbols. Only the coastal areas are named and illustrated with flags that signify the territorial rule over its segments. The ocean area is filled with symbols – compass roses, ships that carry different flags and winds, personified as human heads. In this manner, de la Cosa's map carefully presents the New World as an unknown and unmarked territory. Its green vastness stands in contrast to the Old World crowded with cities ruled by different kings, being the stage of many events, real or fictional, whose roots can be traced to Biblical times. And while on the territory of the Old World the division between Us and Them (i. e. Gog and Magog) is clearly stated, the New World is a blank slate that remains to be filled. The depiction of any pictorial content is avoided, including the assumptions on eventual inhabitants. The positioning of St Christopher, the protector of travellers, as well as the Virgin with Child on the newly discovered territory, along with Spanish flags, ships and the division meridian, suggests that the map strives to communicate the political realities on the newly discovered territory, more precisely establish one own's borders and visually “occupy” this space.[17]

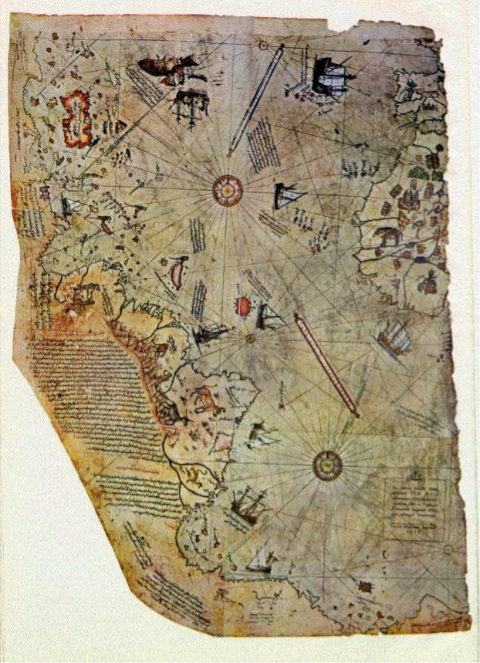

The map of Piri Reis represents, on the other hand, a unique example of an iconographically rich early modern map in the Ottoman tradition that, made in the style of portolan charts, belongs to a different cultural and functional (nautical navigation) milieu. Despite this, it is hard to categorize the map of Reis (Fig. 2) among early modern maps precisely because of the multi-faceted information and different interpretative possibilities that it offers, which surpass the established culturological determinants. Moreover, its author is an exception even in the framework of Ottoman cartography. The map is only partially preserved and the part that survives shows the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 58 illustrations, many of them depicting live beings, the fact that disputes their avoidance on the maps from the Ottoman period, especially as maps were considered useful in the war against nonbelievers (Saricaoglu 2015, 132-185).

Fig. 2. The map of the known world of Piri Reis, 1513, Library of the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, H 1824. (Isipek and Perinčić 2013). / Slika 2. Karta svijeta Pirija Reisa iz 1513. godine, Knjižnica muzeja Topkapi Palače, Istambul, H 1824. (Isipek i Perinčić 2013).

The 1513 map of the world holds an abundance of inscriptions in the Ottoman language that offer additional information and ease of reference. Piri Reis shows various types of ships and almost everyone is accompanied by an inscription on the type of ship or historical events related to it, such as the accidental discovery of the Azores by the Genovese. Piri Reis also provided information on human and animal inhabitants of certain areas. For example, rulers are depicted wearing their traditional costumes with related information: on Ebû Abdullâh el-Kâ'im bi-Emrillâh of Marocco, or Mensa Musa of Mali. Even though depictions of many animals belong to the medieval iconographic tradition, the peculiarity of this map are depictions of parrots, which do not have earlier parallels.[18] Saricaoglu claims that in the Ottoman tradition parrots are connected to the New World and on Reis' maps they indicate newly discovered areas.

Still, the map of Piri Reis bears many fantastic elements[19], some of which he claimed he adopted from older mappae mundi. The medieval legend of the journey of St Brendan is illustrated with a miniature of a carrack and human characters sitting on the back of a whale and building a fire, which is described in an accompanying inscription. The most interesting in the context of this paper among the elements of the medieval iconographic tradition are the depictions of monstrous races, located in the newly discovered areas of today's Brazil. As in the case of the map of Juan de la Cosa, Cinocephalus and Blemmy are depicted, the first shown dancing while holding hands with a monkey and the second sitting, also in some form of an interaction with a monkey. The accompanying inscriptions explain that “the beasts of this type inhabit mountainous areas of this land, while coastal areas are populated by communities of people with their own languages”. Additionally, Blemmys are described as “harmless and submissive”. This example also shows the marked difference that was already noted on the medieval mappae mundi of Barbarians, i. e. the type of Otherness that is possible to integrate into civilized society, as seen on the depictions of rulers in their traditional costumes and the mentioned communities which “have their own languages”, and Savages, the Otherness that is completely foreign and incomprehensible, which, in this case, is symbolized by Blemmy and Cinocephalus, located in the wilderness of the newly uncovered continent.

The key difference between the two analysed maps, in our opinion, lies in the fact that the map of Piri Reis has a more enhanced exploratory character, as evidenced by the numerous information that he gives to the reader – the depictions of ships, rulers, real and fantastic humans and animals. The wild and unexplored parts of the world are filled with fantastic creatures, which in this case remained those from Antiquity and the medieval tradition, but they are not located in Africa, India or the rest of Asia as was the case in medieval cartography, but are moved across the ocean, into the New World, which now adopted the role of the wild and unexplored world that, as Reis tries to show, is yet to be explored. It must be emphasized, however, that Reis used as his sources the maps from both the Christian and Islamic milieu to create, as he himself stated, a unique map. The profession of Piri Reis as an admiral, as well as his privateering activities in the Mediterranean, demanded that he be well-informed, including collecting information coming from adversaries. Such a choice of illustrations can be explained as a unique example of syncretism in the cartographic tradition, exemplifying the globalist processes that would initiate the Age of Discoveries, as well as pointing to a completely new understanding of the world that would be shaped as a result of said processes.

7. Images on Maps of the World from the 16th and 17th Centuries

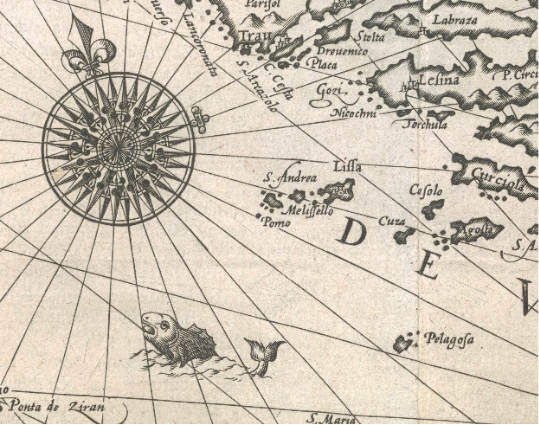

Along with functional navigational elements, nautical charts preserved some aspects of the medieval cartographic tradition (symbols, saints, Christian motifs) that were carefully balanced with newer geo-cartographic information, content that is necessary for navigation. Those were most often compass roses and rhumb lines, maritime routes or course lines. They, along with compasses, were used to determine the geographic position and course of navigation and in so doing provided orientation in the open sea. The function of nautical charts positioned them as a crucial new tool for navigation that, along with the compass and astronomical instruments (Jacob's staff, quadrant, astrolabe etc.) enabled sailing far from shore and its terrestrial markers. Along with meridians and parallels, rhumb lines (mathematically constructed net of lines that connected the same direction of winds, 64 of them) have enabled the measure of course, i.e. the recalculation of direction and distance between certain points of a maritime route.[20] The initial compass roses, no matter their functionality, were decorated in the Baroque style, often with an abundance of detail. On the charts showing the Adriatic, the rich symbolism was also not unusual, with the aesthetics of compass roses especially highlighted. The concrete strategical conflicts between Venice and the Ottomans on the territory of the eastern Mediterranean and the Adriatic are in some cases reflected in variations of details on compass roses.

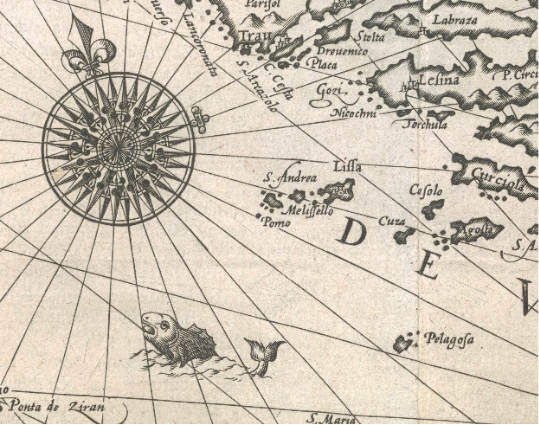

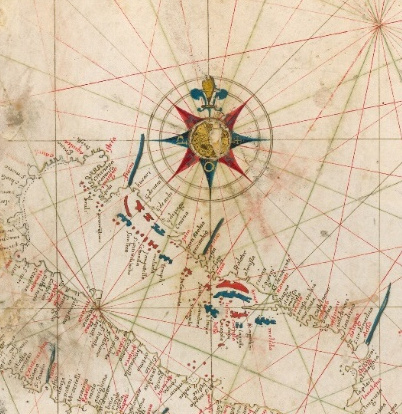

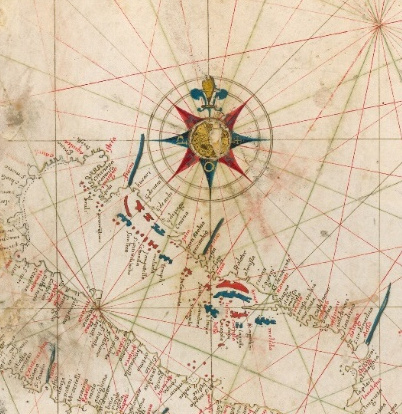

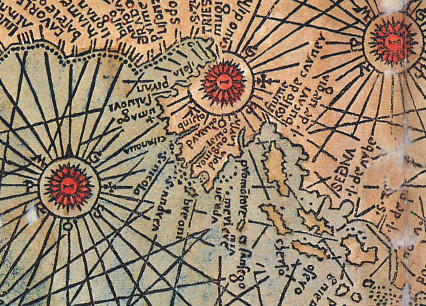

One of the standard models, most often used among the Mediterranean (eg. Catalan) cartographers of the Adriatic was marking north on the compass rose with the symbol of a lily flower (Fleur-de-lis) (like on the Barents chart,Fig. 3,Barents 1595). In addition, on some compass roses east was marked with a symbol of the cross[21], indicating the direction of Christ's grave (such as portolan charts of Volcius,Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. The chart showing the Adriatic Sea, detail, W. Barents, 1595, Tabula Hydrographica…, The Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries (with permission of the HACHAS project, note 3) / Slika 3. Karta Jadrana, isječak, W. Barents, 1595, Tabula Hydrographica…, The Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries (uz dozvolu HACHAS projekta, bilj. 3)

Fig. 4. Vincentius Demetrius Volcius, The chart of the Adriatic, 1593, (detail) National Library of Finland, Maps, The Nordenskiöld Map Collection, N, Kt, 103b (Novak 2005, 267) / Slika 4. V. D. Volcius, Karta Jadrana, 1593, (isječak) National Library of Finland, Maps, The Nordenskiöld Map Collection, N, Kt, 103b (Novak 2005, 267)

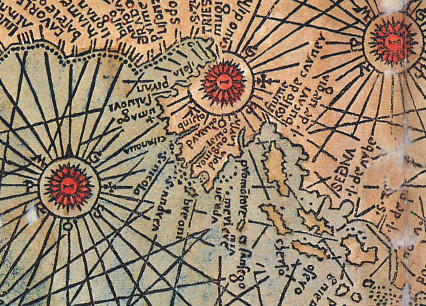

Although this might only be artistic expression and not necessarily related to the original function of the map, it is evident that in addition to the signs of the eight principal winds (as well as half-winds) and the fleur-de-lis marking north, on some compass roses from the Western portolan charts of the Mediterranean east is marked with the symbols of the Knights Hospitaller or Templars (Coppo's portolan chart of the Adriatic,Fig. 5) (Martín-Gil, Martín-Ramos and Martín-Gil 2005, 286). Such religious symbolism is the continuation of the use of Christian iconography from earlier periods, as seen in the depictions of saints, oversized churches, symbols of church orders (such as the Templars) and similar content on charts. It was also an amalgamation of old symbols and new navigational utilitarianism that symbolically identified the Adriatic as a part of the European (Mediterranean) navigation basin, sharing the same cultural and economic influences and tradition. This also suggested greater imagological and communicational capacities of illustrations on maps oriented towards a wider circle of users.

Fig. 5. Pietro Coppo, 1525, the portolan chart of the Adriatic (detail) (Slukan Altić 2003, 368) / Slika 5. Pietro Coppo, 1525, Portulanska karta Jadrana, isječak (Slukan Altić 2003, 368)

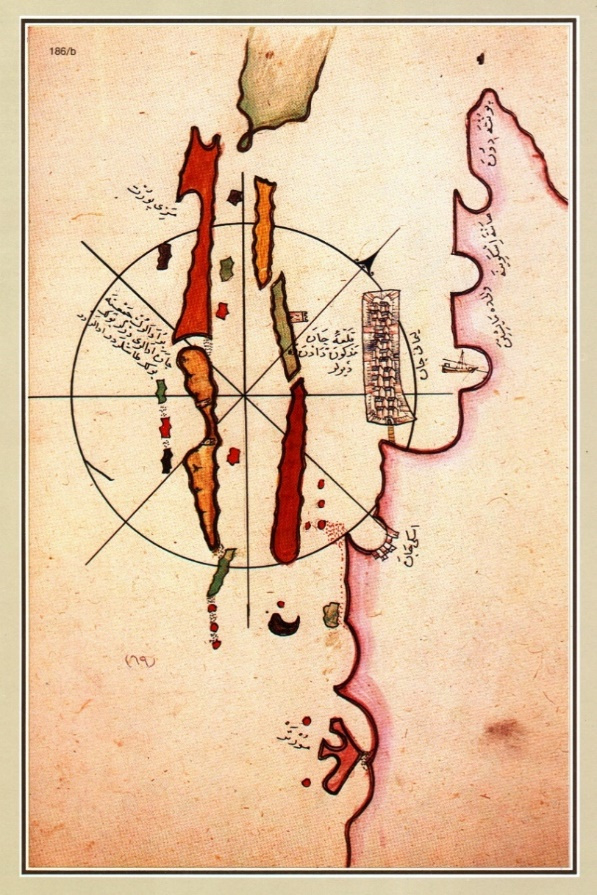

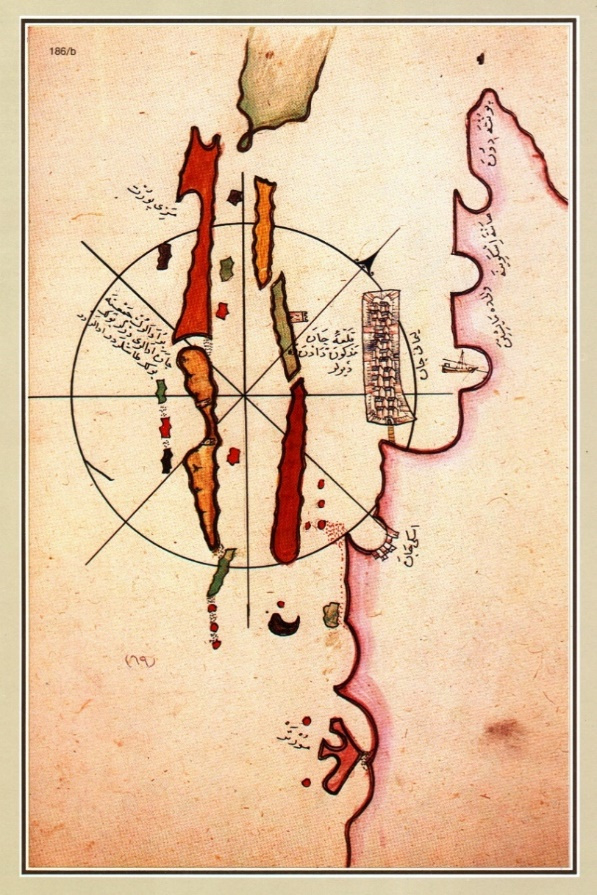

It is evident that on compass roses of Ottoman authors there are no explicitly religious symbols.[22] Even though in some elements Piri Reis follows his Western sources, such as putting the fleur-de-lis in some cases to mark north[23], it is probable that he uses it for purely decorative purposes, without knowing the complex Christian symbolism behind it. Furthermore, he did not use any other, Christian or Islamic, religious symbols in compass roses (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Piri Reis, isolario of Zadar (detail), Kitab-i Bahriye 1527, Aya Sofiya, (Novak and Mlinarić 2005, 348) / Slika 6. Piri Reis, izolar Zadra (isječak), Kitab-i Bahriye 1527, Aya Sofiya, (Novak i Mlinarić 2005, 348)

Confrontation of the Christian West, notwithstanding the conflicting interests of the Venetians and the Habsburgs, and the Islamic East during the rule of Sultan Suleiman al Kanuni (the Magnificent) is visible on the maps of the Western tradition, reflected in the way in which the territory that shares the economic, social and cultural tradition along with the Christian faith, and whose integral part was the Eastern Adriatic, is represented. The western political forces did not, in so doing, necessarily differentiate between the canonical jurisdictions on the former Roman territory and expressions of particular political ambitions, evident in the dominant Venetian Republic assuming the role of the ruler of the entire Adriatic. Piri Reis, as the representative of the Eastern tradition, does not show the same pretentions. Such discrepancy of narratives between western and eastern demonstrations of affiliations shows that in the West the complex communication and image-creating capacities of the map are aimed at a wider or different audience. In such circumstances the Eastern Adriatic territory, strategically positioned between the crescent moon and the cross as symbols of its rule, represented the clash between the interests of Venice and the Ottoman Empire in the period of insecurity, as well as the maintenance of complex mercantile maritime routes between the East and the West. The crossroads of the complex social interactions and differences (on the basis of political affiliations, class, culture, ethnicity, age, sex, economic power or richness) is evidenced in visual messages on old maps. It is interesting that the work of the Ottoman cartographer was influenced by older nautical charts of the Mediterranean to a greater extent than classical Islamic miniature cartography that is more similar to medieval non-critical Christian O or T-type maps (Mlinarić 2019, 369).

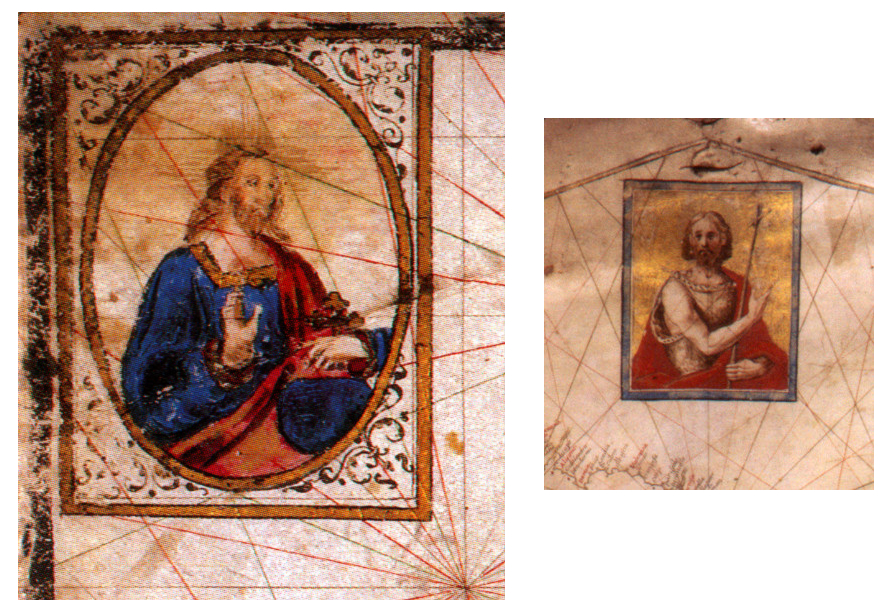

A different sort of “ancillary” religious decorative symbols can be found on portolan charts of Vincentius Demetrius Volcius (Fig. 7a andb). Small images of the Virgin, Christ or patron saints are incorporated in the corners of charts to whom sailors could turn for help and protection when facing adversity at sea. There are also other miniatures that serve as pictorial decorations, such as an “allegorical ship of Christianity” shown on the map of the administrative division of Venetian Dalmatia by the official cartographer of the Republic, Vincenzo M. Coronelli. The Ottoman presence in the Dalmatian hinterland is indicated on the map with an appeal for joint resistance of Italian and Croatian Christians to the Muslim enemy in an engaged propaganda message (Coronelli 1690;Mlinarić and Gregurović 2011, 360).

Fig. 7. A. Portolan chart by Volcius MARE OCEANO (detail), 1592, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, (Novak 2005, 256) b. Portolan chart of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea by Volcius, detail 1595, Newberry Library, Chicago, (Novak 2005, 270) / Slika 7. a. Volčićeva portulanska karta MARE OCEANO, isječak, 1592, Biblioteca National, Madrid (Novak 2005, 256) b. Volčićeva portulanska karta Sredozemlja i Crnog mora, isječak 1595, Newberry Library, Chicago (Novak 2005, 270)

Since the depictions of ships on medieval maps also served as interpretations of Biblical themes (such as Noah's ark on the Ebstorf map,Die Ebstorfer Weltkarte 1234), the informative accuracy of the depictions changed with time and the evolution of cartography, especially in the case of nautical charts. They depended primarily on the scale of the map (or chart), which is why due to the generalization of content the images of ships were excluded, and when they did appear, they were usually schematic and functioned as decorations on empty spaces of the map. Eventually, on the maps of the known world various images of ships started to appear, as on the 1513 Piri Reis map. Although they are stylized and schematic, they do show some difference in type, function, tonnage and origin. Sometime later, the more knowledgeable local cartographers, such as Italians Pinargenti or Camocio put illustrations of sailing ships with information on their size and function on their maps of the Adriatic (Kozličić 1995, 123,138-139;Camocio 1571).

Early modern maps of Croatian lands usually communicated ideological or political pretensions in various ways through their visual imagery, including the imperialistic tendencies of Venetian or Austrian cartography. Those tendencies were usually expressed with visual “occupation” of the space on the map that at the time was not under the rule of the nation the cartographer belonged to (Mlinarić and Miletić Drder 2017, 48-49). On the Eastern Mediterranean, the iconographic elements (flags, weapons of war, ethnic (folk) costumes etc.) spanning from those on the graphic scale to the more frequent ones incorporated in title cartouches, reminded of the long-lasting conflicts between the Christians and the Muslims. “Western” cartographers emphasized the classical (Roman) identity of the Adriatic, the medieval Christian kingdoms and the Mediterranean or Central European identity and affiliation of the Croatian lands up until the late 18th century, at the same time refusing to acknowledge the Ottoman neighbours as a military and strategic threat of the early modern period.

When mapping new and unknown lands, the fear of the unknown was an important aspect of this process. Along with the images of unusual world of flora and fauna, the representations of humans carried the information on people inhabiting certain territories. On the medieval maps in the Biblical tradition, the authors use images of religious or mythological characters, monstruous and hybrid humans on parts of the African continent as an identification model for expressing alterity based on ethnological information and different categorization of the exotic. [24] Usually, such images characterized distant and unknown lands, such as the southernmost continent (Antipodes). The symbolism of such mythological depictions was used to signify different climates and other physical prerequisites that differentiated Europeans from the peoples of the New World who are not only Others and different[25], but sometimes also frightening (inhabitants of eastern Africa with canine heads or characters of Piri Reis in Brazil)[26]. This could also be used to justify the need for missionary expeditions to baptize and familiarize those exotic and “wild” indigenous peoples (Harley and Woodward 1987, 332). However, with time the epithet of new and unknown transferred from one object of interest to another. With the discovery of new continents, the exotic and ultimate Others became peoples who inhabited lands increasingly further from Europe, so Ortelius or Piri Reis locate them in South America or closer to the Poles[27] Unlike, for example the Venetians, cartographers less acquainted with the Adriatic Sea, such as Willem Barents, considered this area equally exotic, so he put gigantic monstruous sea creatures in its waters[28]. On a similar note, on the map of Istria by Bertius, the depiction of a sea monster in its territorial waters indicates it as “wild and unknown territory”, at least to a part of Dutch map[29]. On the other hand, the authority such as Gerhard Mercator highlighted his interest for the Adriatic with depictions of equally random decorative sailing ships[30], but at least he did not try to scare his readers with frightening monsters (Kozličić 1995, 174-179, 201).

The analysis of the chosen maps has shown that up until the 18th century imperial cartographic traditions used the visual perceptions of Otherness as defined above, in the forms of Barbarians or Savages, which could through this technique be alienated from civilized society and exoticized as unknown and different, and even be completely socially excluded.

8. Conclusion

This interdisciplinary research on the diachronic and synchronic level showed the evolution of visual motifs and symbols originating from medieval maps of the known world (mappae mundi) on early modern maps of the world, with a special emphasis on the Croatian territory. Along with medieval maps from Ebstorf and Hereford, the earliest early modern maps of the world of the nautical tradition – the map of Castilian cartographer Juan de la Cosa and Ottoman admiral Piri Reis were also used as primary sources, viewed as examples of different cartographic traditions mapping the same space, using similar elements but with different intentions. By conducting a qualitative analysis, a cartographic comparison of the mentioned sources and other early modern maps was used that are in a cultural sense tied to the Northeastern Adriatic area – portolan charts of Vincentius Demetrius Volcius and Pietro Coppo, as well as the maps of Venetian cartographers Coronelli, Barents and Bertius.

The analytical part of our research can be divided into two segments – the first is a synchronic analysis of the maps of the Old and New World stemming from different cartographic traditions. The maps of Juan de la Cosa and Piri Reis were created approximately at the same time, at the beginning of the 16th century. A comparison of iconographic elements has shown that both cartographers borrowed heavily from the Western medieval tradition, as evidenced by using iconographic motifs of monstrous races. A detailed analysis has shown that the medieval motifs that were borrowed from bestiaries found also on contemporary mappae mundi were mostly used to denote the wilderness, unknowingness and “Otherness” of a certain space. Even though the map of Juan de la Cosa, made in the western, Christian tradition inherited other elements of medieval Christian cartography, they are mostly reserved for the space of Africa and Asia (i.e. parts of the Old World), continuing thereby the traditional practice of their mapping. In contrast to the already known continents, the cartographer depicted the New World as a vast space meticulously marked by flags and ships suggesting political, i.e. imperial pretensions of the author and the cartographic tradition in which he was formed. Piri Reis denotes the wilderness of South America in a similar, medieval manner, as a space that is yet to be explored. His intention was to make a didactic map, as evidenced through depictions of other animals, mainly birds and different types of ships, accompanied by an abundance of inscriptions that give additional information to the reader.

The second part of the diachronic analysis focused on most frequent and iconographically most informative pictorial elements on early modern charts of the 16th and 17th centuries, which also borrow from the medieval cartographic tradition in ideological (Christian) positioning within the space of the known world. Examples are fantastic animals that on those maps retain a purely decorative role of filling the empty spaces. They are combined with a much subtler role of marking the wild and undiscovered territories of the New World and requirements of the new, utilitarian navigational purpose of nautical charts, as seen in richly decorated compass roses and rhumb lines. The choice of visual images depended not only on map (chart) purpose and users, but also on the available geographic knowledge on one hand and the expertise of its author on the other. It was precisely through the decoration of geographic-nautical elements that the political and religious messages were communicated, mostly focused on marking one's own space contrary to the space of the Others. One example is placing the images of saints inside compass roses or decorative cartouches on maps, or even in more subtle details – choosing the fleur-de-lis symbol or the symbol of a cross to mark north on a compass (or east in some cases). Such visual marking of one's own space is especially evident on examples of Venetian charts of the Adriatic in the chosen period, when religious and political domination against the Ottoman enemy was marked with an emphasis on Christian motifs and depictions of the Others as less civilized Barbarians – in ethnic costumes and with strange, blasphemous gestures. The depictions of fantastic sea monsters or ships were a separate category, as in the Western tradition they maintain a mostly decorative function, although some images of ships contribute to a general didactic role of the map.

The conducted analysis of the visual images on maps has proven itself as a useful upgrade to imagological research of early modern maps. Based on the chosen examples, it was determined that, notwithstanding the conflicting narratives of different epochs or cartographic traditions (western European/Christian and Ottoman/Muslim), they reflect many similarities and continuities in using iconography to depict the known world and exotic imagology as a substitute to real geographic information in depicting the unknown Others.

1. Uvod

Velika geografska otkrića predstavljaju pretpostavku, ali i izazov za pojavu novih i praktičnijih kartografskih reprezentacija poznatoga svijeta. Upoznavanjem Novoga svijeta i dotad nepoznatih kontinenata interes kartografskih korisnika usmjerava se više na praktična znanja o njihovom geografskom izgledu i udaljenosti između pojedinih dijelova nego na ideološko reprezentiranje poznatoga svijeta iz teološko-kršćanske perspektive kakvo je dominiralo srednjovjekovnom samostanskom kartografijom. Pored kartografsko-geografskih informacija simbolika ranonovovjekovnih pomorskih karata sitnijeg mjerila i novih karata svijeta ogledala se u specifičnoj dekorativnosti, odnosno ikonografskim osobitostima poniklima u okrilju razvitka srednjovjekovne umjetničke doktrine. S druge strane, pomorske su karte na početku ranog novog vijeka u okviru svoje plovidbene funkcije razvijale i dodatne kvalitete, poput preciznije orijentacije iskazane kompasnim ružama i mrežom kompasnih linija – rumba, čime su omogućavale preciznije planiranje i provedbu navigacijskih zadaća.

Cilj je ovog istraživanja bila evaluacija ikonografskih komunikacijskih mogućnosti dekorativnih likovnih elemenata i kompleksnih simbola na kartama svijeta, uključujući i pomorske karte Novoga svijeta, tijekom srednjega i ranoga novog vijeka analizirajući pritom i prostor na njima prikazanih hrvatskih zemalja.[1] Pored simbola u matematičko-orijentacijskim elementima karte, prezentacije realnih (stvarnih) i apstraktnih teritorija ovisile su o kulturno prihvatljivim konceptima prostora. Autorice su usporedile likovne prikaze, odnosno likovne reprezentacije prostora s karata različite provenijencije (od zapadnoeuropske do mletačke i osmanske) i namjene u sinkronijskoj i dijakronijskoj perspektivi, u rasponu od kompasnih ruža, prikaza brodova, vjerskih motiva poput prikaza svetaca zaštitnika do etnografskih obilježja ili elemenata faune nastojeći proniknuti u njihova različita, posebno simbolična značenja.

Uz geografsko-kartografski sadržaj karata sredozemnog bazena do sada su tek rijetko istraživači, pa i povjesničari umjetnosti, u fokus stavljali ilustrativno-dekorativni sadržaj karata i simbolične poruke. Cilj usporedbe bio je pronalazak sličnih kartografskih komunikacijskih obrazaca ili kolaborativnih praksi, čak i u suprotstavljenim interesima različitih imperijalnih kartografija. A one su se kretale u rasponu od korištenja karte kao argumentacije, odnosno opravdavanja ekonomskih ciljeva, do kulturnih, vjerskih ili vojnih interesa koje su kartografi izražavali kroz svoje radove stvarajući slike o prostoru koji su prikazivali. Veliku je ulogu pritom odigrala raspodjela moći, odnosno potreba za stjecanjem teritorijalne jurisdikcije i/ili gospodarske supremacije nad nekim prostorom. Upravo je spomenuta alternativna uloga komunikacijskih mogućnosti karte, uz primarnu orijentacijsko-plovidbenu svrhu, u fokusu ovoga rada. Preispitan je i način na koji se likovni sadržaj mijenjao od srednjeg do ranoga novog vijeka na kartama različitih prostora i unutar različitih kartografija, vezano uz praktičnu (plovidbenu) svrhu karte s jedne strane, ali i ulogu karte kao sredstva komunikacije i povijesnog svjedočanstva s druge. Posebna je pažnja posvećena, sukladno dostupnim izvorima, načinu kako su na reprezentacijama cijelog poznatog svijeta toga vremena bili prikazani, odnosno koliko su bili poznati današnji hrvatski prostori.

2. Metode, izvori i pristup

Metodološkim smo pristupom komparativne kvalitativne analize ilustrativnih kartografskih sadržaja s izabranih karata nastojali identificirati određene obrasce komunikacije kartama, točnije argumentiranja ili pak mijenjanja poimanja svijeta u sinkronijskoj i dijakronijskoj perspektivi. Takvim smo interdisciplinarnim pristupom, na tragu recentnih historiografskih istraživačkih paradigmi poput prekograničnosti ili integrativnosti primijenjenih na ranonovovjekovne i još ranije arhivske izvore, odnosno diskurzivnog pristupa kulturalne kartografije, neokartografije i imagologije, analizirali uporabu izabranih likovnih elemenata ovisno o ideologiji, konfesionalnoj pripadnosti ili kartografskoj tradiciji kojoj su pojedina karta, odnosno njen autor, pripadali. Kartu smo, stoga, promatrali kao simboliziranu grafiku, odnosno sliku subjektivizirane geografske stvarnosti i povijesni konstrukt sastavljen od elemenata simboličkoga vizualnog zapisa koji nikada ne gubi vrijednosna obilježja kulturne reprezentacije (Harley i Woodward 1987, XVI, 506).

Između odabranih izvora detaljnije je analiziran likovni sadržaj na ranonovovjekovnim kartama portulanske tradicije, dok su srednjovjekovne karte korištene kao supstrat za promatranje razvoja (kontinuiteta i diskontinuiteta) uvriježenih likovnih simbola u različitim kartografskim tradicijama.

Izabrana je građa različite provenijencije, tipa, geografskog diskursa, odnosno pristupa prostoru. Iako su spomenuti izvori do sada znanstveno istraživani (Škiljan 2006)[2], njihova likovno-umjetnička kvaliteta i višeslojne grafičke osobine informacija koje odašilju uglavnom nisu znatnije elaborirane. Dio je ovog rada, stoga, usmjeren i na ikonografsku analizu srednjovjekovnih karata, poput dviju najvećih i najpoznatijih iz XIII. stoljeća – karte iz samostana u Ebstorfu (Die Ebstorfer Weltkarte, 1234) u Donjoj Saksoniji te karte iz katedrale u Herefordu (Hereford MappaMundi, 1300;Hereford Cathedral Map, 1300) u Engleskoj. Za kasnija su razdoblja analizirane portulanske karte i pomorske karte, ali i karte svijeta europskih kartografskih škola te one nastale u okvirima osmanske kartografske produkcije unutar koje je reprezentativan opus Pirija Reisa[3].

3. Teorijsko-pojmovni okvir analize likovnih prikaza na starim kartama

Estetska je komponenta kartografije pobudila znanstveni interes relativno nedavno, dok je prethodno smatrana sporednom u usporedbi sa znanstvenim i tehnološkim aspektima izrade i korištenja karata. U novije se vrijeme utišavaju[4] znanstvene struje koje su osporavale umjetničku vrijednost karata u prethodnim desetljećima, kao i njihovu komunikacijsku mogućnost srozavajući ih na model dosljedne primjene uvriježenih pravila bez osobite subjektivne uloge kartografa (Karssen 1980: 121). Premda je umjetnička vrijednost karte počivala na ljepoti izraženoj u kompoziciji, dojmu i harmoniji elemenata poput kartografskih znakova (uključujući njihove točkaste, linijske i arealne oblike, teksture i boje), kartuša, kompasnih ruža, pisma, crteža životinjskih i ljudskih likova ili heraldike, ona se od umjetničke ornamentike i subjektivnosti nekog drugog umjetničkog djela ipak razlikovala jer je manje trpjela apstrahiranje sadržaja i korištenje nestandardiziranih simbola (Mlinarić i Miletić Drder 2017, 24-25). Premda je potreba preciznosti u prikazu prostornih odnosa sigurno smanjivala manevarski prostor umjetničkog izražavanja u odnosu na ostvarenja u likovnoj umjetnosti, valja priznati da je sveobuhvatnija standardizacija izrade karata ipak pojava kasnijeg datuma. Prve natruhe standardnoga mogu se naći u kanonskim radovima renesansnih kartografa nastalima na temelju opažanja iz autorove (subjektivne) perspektive, ali zamah dobiva tek u 18. stoljeću s revolucijom u kartografskoj proizvodnji temeljenoj na prethodnim izmjerama terena. Iako su formalni aspekti procjene estetike karata poput linije, boje i kompozicije važni, na starim je kartama, osobito onim najranijim, uz njih posebno bitna bila i ikonografska interpretacija simbola i motiva na karti koja je nadilazila estetsku funkciju. Ikonografska je metoda u ovom radu korištena za identificiranje, klasificiranje i interpretaciju slikovnog sadržaja na kartama, s ciljem razjašnjavanja njegovog značenja i smisla u sociopovijesnom kontekstu.[5] U ovom slučaju ikonografska analiza slikovnih simbola na kartama doprinosi razjašnjavanju reprezentiranih predodžbi ili imagema o drugom/drugačijem u analiziranim kartografskim izvorima, točnije, predodžbi o vlastitom prostoru te prostoru Drugih – dihotomiji koja je jednako aktualna u srednjovjekovnim i ranonovovjekovnim kartama različitih primarnih funkcija.

Naime, tijekom srednjovjekovnog i ranonovovjekovnog razdoblja karta je kao prostorni prikaz, ali i imaginarij, bila sastavljena od autorove osobne interpretacije ili nadogradnje na poznate dijelove transkribirane geografske stvarnosti. Dijelom je reflektirala njegov vjerski, etnički i kulturni identitet, njegovu viziju ili reprezentaciju prostora, a time i političke programe i pretenzije (Mlinarić i Gregurović 2011, 98). Pritom su te kartografske slike kulturnih reprezentacija stranih zemalja, osim posredovanja kartografskim kodom, bivale „opterećene“ složenim odnosima kulturnoga pozicioniranja i odnosa moći, čak i u odabiru informacija kojima su raspolagale, ali i kompleksom konotativnih značenja koja je autor oblikovao svojim posredovanjem informacija (Škiljan 2006;Dukić i dr. 2009). Kartirani su prostori i identiteti stanovnika, stoga, svjedočanstva o prostornoj organizaciji, ali i poznavanju novijih geografskih informacija koja su mogla biti opterećena različitim statusima različitosti i „Drugosti“ (Otherness) od političke podložnosti, kulturne, etničke ili vjerske pripadnosti, dobi, spola ili ekonomskog statusa. Pronalazak subjektivnog na karti iziskivao je čitanje između redaka primijenjenog kartografskog ključa, posebno ukoliko se uzme u obzir suvremeno obilje diskurzivnih varijanti.[6] Kroz mentalnu konceptualizaciju i rekonstrukciju prostora na zapadnjačkim kartama najupečatljiviji su simboli u službi svjetonazora, odnosno preispitivanja čovjekova mjesta na Zemlji te ideologija, od vjerskih (npr. kršćanskih ili islamskih) do svjetovnih (npr. socijalnih, vezanih uz izrazitu društvenu stratifikaciju toga vremena ili političkih) (Mlinarić 2019, 366).

4. Komunikacijski potencijal srednjovjekovnih programatsko-ideoloških karata svijeta (mappae mundi) i ranonovovjekovnih plovidbenih karata

Spomenute su vrste starih karata odašiljale različite poruke vezane uz svoju namjenu i poznata geografska znanja. Srednjovjekovne samostanske mappae mundi, npr. O ili T karte, s prikazom triju poznatih kontinenata Starog svijeta[7], kao što je to karta iz Hereforda (sl. 1), bile su bogate simbolima i funkcionirale kao političko-kulturna edukativna poruka, odnosno ideološki obojen geografski kompendij (biblijskih) znanja o poznatome svijetu iz teološke perspektive. Premda, kao i druge karte, predstavljaju generičke prikaze koji pomažu prostornom razumijevanju stvari, koncepata, uvjeta, procesa ili događaja (Harley i Woodward 1987, xvi), mappae mundi nemaju utilitarnu funkciju karte da što vjernije prenesu geografski prostor i prostorne odnose na dvodimenzionalni medij radi olakšavanja orijentacije te stjecanja kompleksnijih uvida u geografska obilježja. Za tu im ulogu nedostaju elementi matematičke osnove, od kartografske projekcije i s njom povezane koordinatne mreže do mjerila. Fokus im je bio na filozofskim i religijskim principima i didaktičkoj ulozi pojašnjavanja harmonije Božjeg poretka i stvaranja (Barber i Delano-Smith 2018, 117;Harley i Woodward 1987, 342). Premda postoje i primjerci velikih dimenzija, poput karte iz Hereforda, većina se tih karata nalazi u manuskriptima. Zbog toga su bile izrazito malih dimenzija i sitnog mjerila te nedovoljno detaljne, stoga i slabije geokartografski informativne, posebno u kartiranju kopna i obalnih linija (Edson 1997, 11). Biblijske su scene kršćanske ikonografije bile posebno važne, pa iako je ideološki autoritet mogao opravdati takav sadržaj do geografskih otkrića, nakon njih nije uspijevao odgovoriti izazovima upoznavanja novih kontinenata, a pogotovo nije mogao praktično služiti pomorcima na prekoatlantskim pučinskim pomorskim rutama. Promatrajući hrvatske prostore na takvim ranim kartama svijeta, detalj Jadranskog mora (slika 1, isječak) potvrđuje njenu namjenu. Naime, Jadransko more nema prepoznatljivu obalnu liniju čak niti u konturama jer je ukupni prikaz ionako u službi ideološkog oslikavanja šireg prostora, odnosno isticanja važnog i predimenzioniranoga Rima u susjedstvu koji je i tekstualno centralno pozicioniran (Roma caput mundi...).

Za razliku od njih, utilitarna[8] svrha portulanskih, odnosno pomorskih karata kao tipičnih tematskih karata, usmjerena je na precizniji geografski prikaz linije obale i otoka, posebno istaknutih objekata terestričke navigacije i bilježenje njihovih geografskih imena. Pojava tiska pridonijela je reotkrivanju starih antičkih dijagramskih shema svijeta i renesansi Ptolemejeve kartografske baštine upravo u doba otkrića Novog svijeta, dok je prekooceanska plovidba nametnula potrebu za kartografskim realizmom i preciznijim pomorskim kartama (Barber and Delano-Smith 2018, 125). Uvode se matematičko-konstrukcijski elementi poput rumba i mreže paralela i meridijana u cilju što točnijeg prikaza Zemljine površine u svim njenim dijelovima, pri čemu same plovidbene karte grafički zaokružuju informativnu cjelinu plovidbenih priručnika. Ukupna je svrha kvalitetne karte omogućiti određivanje geografskog položaja i prostornih odnosa među prikazanim geografskim objektima. I dok je renesansna dekorativnost zahtijevala bogatiju estetsko-vizualnu kvalitetu, a humanistička znatiželja i komercijalne potrebe predindustrijskih društava (ancien regimé), uvođenje novih tehnika, tehnologija i informacija o novim zemljama, plovidbene su karte sve više, umjesto estetike, uvažavale kvalitetu geografsko-prostorne preciznosti i informativnosti.

Zaključno, naglašavanje dekorativnosti bilo je obrnuto proporcionalno potrebi za preciznijim geografskim dokumentiranjem stvarnih geografskih odnosa. Kontradiktorno su upravo otkrića nametnula potrebu za što bržom pojavom vizualnih sinteza poznatih geografskih podataka, ali i dorađivanjem, odnosno temeljitom revalorizacijom srednjovjekovnih mappae mundi. Nadopunjene iskustvenim znanjima pomoraca, srednjovjekovne su karte kao svojevrsni hibridi evoluirale u složenije varijante antičkih karata i karata svijeta temeljenih i dalje na kršćanskoj ikonografiji (Škiljan 2006, 62).

5. Diskusija: Konkretno komuniciranje određenih geokartografskih poruka kartografskom likovnošću

Grafičke elemente s karata, poput kompasnih ruža, jedrenjaka, svetaca, realističnih ili čudovišnih životinja ili pak (terestričkih) markera na kopnu za orijentaciju u plovidbi moguće je korelirati u cilju analize različitih komunikacijskih potencijala karte.

Ikonografski su motivi na srednjovjekovnim kartama svijeta (mappae mundi) ilustracije široke lepeze znanja o svijetu srednjovjekovnog kartografa, pozicionirane na način koji je on smatrao smislenim i koji sa semiološke strane imaju čitav niz značenja. Slikovni se prikazi na izabranim mappama mundi mogu podijeliti, ovisno o svom glavnom tekstualnom izvoru, na biblijske scene i scene iz klasične antike – i to ne samo one mitološke, već i stvarne lokalitete zabilježene u izvorima. Informacije su potjecale iz raznih tada dostupnih srednjovjekovnih kompendija znanja[9], uvelike temeljenih na antičkim izvorima (Pliniju, Herodotu itd.). Osim što su konstruirale poznati svijet u skladu sa srednjovjekovnim sklopom znanja, važna je bila i njihova uloga u oblikovanju identiteta i pripadnosti [10], s ključnom podjelom na Nas i Njih, što je razvidno kroz pozicioniranje slikovnih prikaza unutar poznatog svijeta.

No, osobito je zanimljiva značajka obiju karata i obilje prikaza stvarnih i fiktivnih životinja te raznih plemena i narodnosti fiktivnih karakteristika, manje-više preuzetih iz različitih dostupnih redakcija Plinijeve Naturalis Historiae. Oni se uglavnom nalaze na rubovima poznatog svijeta, u Aziji, a ponajviše u Africi. U središtu se karte, na teritoriju kršćanskog svijeta koji je kartografu blizak, prednost daje prikazima gradova te konkretnim informacijama vezanima uz njihovu povijest. Plemena i narodi koji žive uz sam rub oceana i na njegovim otocima prikazani su potpuno goli, s naglašenim fantastičnim karakteristikama. No usprkos standardiziranom sadržaju, neki su prikazi ponekad bili u službi potpuno drugačije, kontekstom posredovane vrste kartografskog komuniciranja. Primjer je grad Jeruzalem koji na objema kartama zauzima centralnu poziciju. Na karti svijeta iz herefordske katedrale prikazan je kao kružna utvrda jakih bedema, dok je njegova važnost na Ebstorfskoj karti dodatno pojačana prikazom Uskrslog Krista koji izlazi iz groba u trijumfalnoj pozi, u bijeloj halji, držeći križ u lijevoj ruci. Na Herefordskoj je karti nedaleko od Crvenog mora prikazan i židovski narod (označen natpisom Iudei) koji štuje idola Mahuna s naglašenom fizionomijom lica koja se smatrala karakterističnom za tu populaciju, čime autor pribjegava stereotipnom prikazivanju Drugoga.[11]

Od fantastičnih životinja na objema su kartama prikazani jednorozi, bazilisk, grifon, kao najčešće fantastične životinje srednjovjekovnih bestijarija, na Ebstorfskoj je karti prikazano puno više stvarnih životinja, dok Herefordska uključuje i mantikoru, mandragoru, sfingu, fauna, satire itd.,ponavljajući isti model – životinje najčudovišnijih karakteristika prikazane su na rubovima svijeta. Uz uvažavanje primarne svrhe mappae mundi su donekle odražavale i stupanj znanja svog vremena, vidljiv u slabom poznavanju obalnih linija[12]. Bez obzira što je mističnost i egzotičnost grafičkih prikaza bio uzus, razvidno je da jednoroge nalazimo na mjestima očito nepoznatog geografskog sadržaja koji je upravo stoga praktično grafički supstituiran imaginarnim i zanimljivim bićima, što se prakticiralo i kao kartografski koncept i kao pojedinačna praksa.

Izrada je karte ne samo konstrukcija geografske stvarnosti, već i konstrukcija značenja (Duncan i Ley 1993, 331). Već smo istaknuli da je u slučaju obiju mappa mundi zamjetna binarna opozicija između Nas i Njih, dominantne grupe kojoj pripadaju kartograf i njegova ciljana publika, koju karakterizira primarno pripadnost kršćanskom svijetu, i svi ostali koji se u taj obrazac ne uklapaju, a na kartama se osobito ističu te karakteristike koje ih razlikuju od dominantne grupe. Naziv „barbari“, koji se pojavljuje na Herefordskoj karti, još se od drevne Grčke koristi kao skupni naziv za one grupe koje su po svojim karakteristikama inferiorne, a taj se naziv i danas koristi da bi se označila Drugost. Od XII. do XVI. stoljeća taj pojam u svijesti kršćanskog Zapada označava ljude koji nisu kršćani, a k tome se i ponašaju na neciviliziran način (Duncan 1993, 44). Unutar kategorije Drugih Staszak razlikuje grupu koju naziva Barbarima, koja ipak zadržava određenu mogućnost integracije u dominantnu skupinu, te Divljake (Savage) s čudovišnim i neprirodnim karakteristikama nespojivima s funkcioniranjem u uređenom društvu: kanibalizam, golotinja i nedostatak sposobnosti govora. Nadalje, naglašava upravo prostornu komponentu takve Drugosti – civilizacija se širi iz jednog, centralnog mjesta (Jeruzalema, grada, Europe…), a Divljaci nastanjuju njene rubne zone (primjerice Australiju) ili međuprostore (naše šume) (Stazsak 2009, 44-47). U slučaju srednjovjekovnih karata svijeta civilizacija se širi i iz fizičkog središta karte, Jeruzalema, te se prema rubnim zonama povećava koncentracija naroda začudnih karakteristika, dok se Barbare može naći bliže središtu.[13] Takav se obrazac nastavlja ponavljati i mnogo kasnije, s tim da se s širenjem oikumene mijenja percepcija poznatih i nepoznatih krajeva, a s njome i diferencijacija Barbara i Divljaka.

6. Ikonografija na najranijim kartama Novog svijeta − usporedba dviju različitih tradicija

Neposredno nakon Kolumbova otkrića Amerike izrađene su dvije karte izrazito zanimljive za komparativnu ikonografsku analizu − karta svijeta kastiljanskog moreplovca Juana de la Cose (1500) i karta svijeta osmanskoga gusara i potom admirala Pirija Reisa (1513). Iako izrađene u različitim tradicijama, svaka na svoj način uvelike baštine srednjovjekovnu slikovnu simboliku, uz uvođenje nekih novih grafičkih elemenata koji će se ustaliti tijekom kasnijih stoljeća.[14]

Karta Juana de la Cose u svom zapadnjačkom umjetničkom prikazu Starog svijeta prisvaja pojedine fantastične elemente iz srednjovjekovnih mappa mundi, i to rezervirane isključivo za prikaz Starog svijeta, tj. Europe, Azije i Afrike. Najzorniji je primjer prikaz plemena Goga i Magoga, biblijske legende o plemenima koja obitavaju u svojim zazidanim gradovima iz kojih će izaći na Sudnji dan. Ona se u srednjem vijeku i nadograđuje pričom da ih je zazidao Aleksandar Veliki, a u tom se obliku pojavljuju i na srednjovjekovnim kartama svijeta. Primjerice, i na Ebstorfskoj i na Herefordskoj karti Gog i Magog smješteni su uz obalu Kaspijskog mora, na Ebstorfskoj su karti označeni iluminacijom koja prikazuje zazidane ljude koji se upuštaju u čin kanibalizma (Die Ebstorfer Weltkarte, 1234), dok je na Herefordskoj karti prikazan samo Aleksandrov zid koji zatvara planinski klanac, a unutar njega se nalazi dugačak deskriptivan tekst o „raznim užasima“ koje skriva mjesto nastanjeno zlim Kainovim sinovima.[15] Kod Juana de la Cose unutar zazidanog prostora u kojem obitavaju plemena arhitektonski se izdvaja grad koji flankiraju jedan Kinocefal i jedna Blemija, narodi koji se na srednjovjekovnim mappama mundi prikazuju na divljim i dalekim mjestima. Na de la Cosinoj se karti također pojavljuje mitski kršćanski kralj Etiopije Preziber Ivan, također nesumnjivo preuzet iz srednjovjekovne tradicije. Osim njega, na karti Afrike, Europe i Azije pojavljuju se i brojni prikazi vladara koji su ovisno o tome gdje su smješteni, odjeveni ili po zapadnjačkoj ili muslimanskoj tradiciji. Kontrastirani su s prikazima Blemije i Kinocefala, stanovnika Goga i Magoga na krajnjem rubu svijeta, van dosega civilizacije, svijeta Divljaka.

Za razliku od Europe, Bliskog istoka, Afrike i Azije, koji kod Juana de la Cose bivaju označeni raznim slikovnim oznakama – bilo sekularnog, bilo religijskog karaktera[16], Novi je svijet prikazan kao zemlja beskrajnog zelenila, bez ikakvih oznaka na svom kopnu. Obalni su dijelovi imenovani te ilustrirani zastavama koje markiraju prava na pojedine teritorije. Prostor mora i oceana popunjavaju, osim kompasnih ruža, i brodovi koji nose različite zastave te vjetrovi koje personificiraju ljudske glave. Na taj način karta Juana de la Cose pristupa relativno oprezno Novom svijetu kao nepoznatom i neoznačenom teritoriju. Njegovo zeleno prostranstvo uvelike kontrastira Starom svijetu napučenom gradovima kojima vladaju različiti vladari, koji je mjesto brojnih stvarnih i nestvarnih događaja čiji korijeni sežu u biblijsku povijest. I dok je na teritoriju Starog svijeta vidljiva podjela na Nas i na udaljene Druge (najzornije kroz prikaz Goga i Magoga), Novi je svijet prazna ploča koju tek treba otkriti. Prikazivanje bilo kakvog slikovnog sadržaja se izbjeglo, što uključuje i pretpostavke o eventualnim stanovnicima tog područja. Prikazivanje sv. Kristofora, zaštitnika putnika, te Bogorodice s Djetetom, pozicionirane na novootkrivene dijelove karte, zajedno sa španjolskim zastavama te brodovljem i naznačenim meridijanom podjele koji sugerira da se kartom nastojalo prenijeti političke odnose vezane uz otkriće Novog svijeta, točnije, utvrditi vlastite granice i vizualno „zaposjesti“ prostor[17].

Karta Pirija Reisa predstavlja, s druge strane, jedinstven primjer ikonografski sadržajne ranonovovjekovne karte osmanske tradicije koja u stilu portulanskih karata pripada sasvim drugom kulturnom, ali i sektorskom (pomorskom) miljeu. Usprkos tome, teško je Reisovu kartu (sl. 2) svrstati u bilo kakvu kategorizaciju ranonovovjekovnih karata upravo zbog slojevitosti informacija i različitih interpretativnih mogućnosti koje ona sadrži, a koje nadilaze uvriježene kulturološke okvire. Pored toga njen autor i sam predstavlja iznimku, čak i u okvirima osmanske kartografije. Karta je samo djelomično sačuvana i na njoj je prikazan Atlantski ocean. Sadrži ukupno 58 ilustracija, a iznenađuje činjenica da mnoge od njih prikazuju živa bića, što opovrgava uvriježenu tezu da se njihovo prikazivanje na kartama u osmansko doba posebno negativno percipiralo, osobito jer su se karte smatrale pomagalima za borbu protiv nevjernika (Saricaoglu 2015, 132-185).

Karta svijeta iz 1513. obiluje objašnjenjima na osmanskom jeziku koja nude dodatne informacije te olakšavaju snalaženje. Piri Reis prikazuje različite tipove plovila, a gotovo svaki prati tekstualno objašnjenje o kakvom se plovilu radi ili opis izabranih povijesnih događaja, poput slučajnog otkrivanja Azora od strane Đenovljana. Piri Reis se također trudio ponuditi realne informacije o ljudskim i životinjskim obitavateljima pojedinih područja. Prikazuje vladare u nacionalnim kostimima i daje informacije o njima − o marokanskom vladaru Ebû Abdullâh el-Kâ'im bi-Emrillâhu, kao i o vladaru Malija Mensi Musi. Iako brojne životinje pripadaju srednjovjekovnoj ikonografskoj tradiciji, posebnost je karte prikaz papiga, što nema paralele ni u jednom ranijem predlošku.[18] U prilog tome i Saricaoglu navodi da se u osmanskoj tradiciji papige povezuju s Novim svijetom te da na Reisovoj karti one označavaju novootkrivena područja.

Ipak, i kod Pirija Reisa nalazimo brojne fantastične elemente[19], za neke od njih je i sam naveo da ih je preuzeo sa starijih mappa mundi. Srednjovjekovna je legenda o putovanju sv. Brendana ilustrirana minijaturom karake te ljudskih likova koji sjede na kitovim leđima i potpaljuju vatru, što je i opisano u popratnom tekstu. Svakako su najzanimljiviji elementi srednjovjekovne ikonografske tradicije na karti prikazi monstruoznih naroda, i to smještenih na novootkrivena područja današnjeg Brazila. Kao i kod Juana de la Cose, radi se o Kinocefalu i o Blemiji − prvi je prikazan kako pleše držeći se za ruke s majmunom, a drugi kako sjedi u nekoj vrsti interakcije s majmunom. Popratni natpisi objašnjavaju da „zvijeri tog tipa nastanjuju planinske dijelove ove zemlje, dok obalne nastanjuju zajednice ljudi koje imaju svoje jezike“. Dodatno se Blemije opisuje kao „bezazlene i submisivne“. I na ovom je primjeru zamjetno impliciranje razlike, uočene i na srednjovjekovnim mappama mundi, između Barbara, tj. onog tipa Drugosti koji je moguće integrirati u društvo, osvjedočene na prikazima vladara u svojim nacionalnim kostimima i spomenutim zajednicama koje žive na obali te „imaju svoje jezike“, i Divljaka, Drugosti koja je potpuno strana i nepojmljiva, a koju, i u ovom slučaju,kao i kod de la Cose, utjelovljuju Blemija i Kinocefal, smješteni na novootkrivenom kontinentu.

Možda je ključna razlika Reisove i de la Cosine karte u tome što je kod Reisa izraženija njegova vlastita istraživačka znatiželja, vidljiva u brojnosti informacija koje nastoji prenijeti čitatelju – prikazima brodova, vladara i stvarnih i fantastičnih ljudi i životinja. Onaj divlji i neotkriveni svijet koji se popunjava fantastičnim bićima, koja u ovom slučaju ostaju ona iz antičke, tj. srednjovjekovne tradicije, prestaje biti Afrika i Indija te ostali dijelovi Azije, kao što je to slučaj na srednjovjekovnim kartama svijeta, već taj neotkriveni svijet postaje Novi svijet, koji u Reisovom shvaćanju treba upoznati i izučiti. Pritom je važno istaknuti da je Reis kao izvore, između ostalih, koristio karte i kršćanskog i islamskog kruga kako bi stvorio, kako i sam kaže, jedinstvenu kartu. Reisov profesionalni angažman u osmanskoj mornarici, kao i njegove gusarske aktivnosti na Sredozemlju pod državnim pokroviteljstvom, i prethodno su zahtijevale izvrsnu informiranost, što je podrazumijevalo i uvid u informacije s kojima raspolažu protivnici, tj. politički suparnici. Time se njegov odabir ilustracija može promatrati kao jedinstven primjer sinkretizma u kartografskoj tradiciji, što zapravo i ilustrira globalističke procese koji će pokrenuti i otkrivanje Novog svijeta, ali i usmjeriti potpuno novo poimanje svijeta koje će se slijedom tih procesa oblikovati.

7. Likovni prikazi na kartama svijeta XVI. i XVII. stoljeća

Uz pragmatične plovidbene elemente pomorske su karte zadržale i dio srednjovjekovne tradicije (simboli, sveci i kršćanski motivi), ali su ih skladno uključili među nove geokartografske informacije, sadržaje neophodne za plovidbu. Novi su elementi likovno realizirani u obliku kompasnih ruža i mreže rumba, plovidbenih pravaca, odnosno kursnih linija. Njima su uz upotrebu kompasa moreplovci određivali geografski položaj i kurs plovidbe i tako se orijentirali na pučini. Plovidbena je namjena nautičkih karata nametnula kartu kao novi nezaobilazni alat koji je uz kompas i astronomske instrumente (Jakovljev štap, kvadrant, astrolab i dr.) omogućavao plovidbu podalje od obale i njenih terestričkih markera. Rumbi su matematički konstruirana mreža linija koje povezuju isti smjer vjetrova, njih maksimalno 64. Uz mrežu meridijana i paralela, omogućavali su mjerenje kursa, odnosno preračunavanje smjera plovidbe te udaljenosti između određenih točaka na plovidbenoj ruti. [20] Prvotne je kompasne ruže, bez obzira na njihovu utilitarnost, krasila i barokna estetika i nerijetko raskošna kićenost. I na kartama Jadrana je bogata simbolika bila više pravilo nego iznimka, s posebno naglašenom estetikom kompasnih ruža. Konkretni su strateški sukobi na mletačko-osmanskom bojištu istočnoga Sredozemlja i Jadrana ostavili traga na varijacijama u izradi kompasnih ruža.

Jedan je od standardnih modela, najčešće korišten među mediteranskim (npr. katalonskim) tvorcima pomorskih karata Jadrana, bilo označavanje sjevera znakom ljiljana (fleur-de-lis) u kompasnoj ruži (primjer Barentsove karte,sl. 3,Barents 1595). Osim toga, na nekim je ružama istok bio označen simbolom križa[21], sugerirajući smjer Kristova groba (primjer Volčićevih portulanskih karata,sl. 4).

Iako se može raditi tek o likovnom izričaju bez nužne veze s originalnom primjenom, činjenica jest da osim oznaka kardinalnih, ali i vjetrova nižega reda, uz oznake ljiljana za smjer sjevera na nekim kompasnim ružama s portulanskih karata Sredozemlja zapadnjačke provenijencije umjesto križa, nalazimo istok označen simbolom crkvenih redova vitezova ivanovaca ili templara (Coppova portulanska karta Jadrana,sl. 5) (Martín-Gil, Martín-Ramos i Martín-Gil 2005, 286). Takva je religijska simbolika nastavak korištenja kršćanske tradicije i ikonografije prethodnih razdoblja, izražene u likovima svetaca, predimenzioniranih crkava, simbola crkvenih redova (npr. templarskoga) i sličnog sadržaja na kartama. Ujedno je kao hibridna praksa starih simbola i novog plovidbenoga utilitarizma simbolički identificirala Jadran dijelom europskoga (sredozemnog) plovidbenog bazena, iste kulturne pripadnosti, sličnih ekonomskih utjecaja i tradicije, sugerirajući time i veće imagološke i komunikacijske kapacitete grafije s karata koje su bile orijentirane širem i raznovrsnijem krugu korisnika.

Zamjetno je pak da na kompasnim ružama karata osmanskog autora nema eksplicitnih vjerskih simbola.[22] Premda se u nekim drugim elementima Piri Reis naslanja na svoje zapadnoeuropske kartografske uzore, pa uz češće strelice rijetko koristi i simbol ljiljana za označavanje smjera sjevera na karti[23], vjerojatno ga je koristio u dekorativne svrhe, bez poznavanja složene kršćanske simbolike vezane uz fleur-de-lis. On nije koristio nikakve druge, niti kršćanske niti islamske religijske simbole u orijentacijskim kompasnim ružama (sl. 6).