1. INTRODUCTION

The institutional memory plays an important role in Romania, as sport is considered an activity of national interest. This is a relic of the communist era, which symbolised a period of global sporting success for Romanian athletes and sport organizations. Consequently, besides clear and direct political interest that will be presented, both the general population and the media are focused on major competitions such as the Olympic Games, and World or European Championships, orientated dominantly toward high-performance and elite sports. Despite this unified interest, Romania has experienced a decline in achieving sporting excellence, and some scholars have thoroughly examined this phenomenon from different perspectives.2,3,4,5 There are different reasons behind this, but the most dominant notion is the lack of necessary reforms that will depart from the state-centric and elitist approach. More precisely, high-performance sports are still being funded by the public sector, even though a sponsorship law exists to regulate the relationship between beneficiaries and sponsors and define their rights and obligations.6 Although the reliance on state funding remains predominant, even if organizationally speaking, there is also a private sector presence and a legal framework for a sponsorship law, this reform is far from being realized. The role of the public sector and its interplay with the sports movement resulted in the former bypassing existing regulatory regimes in order to utilise sport for non-sporting objectives.7 Accordingly, the development of sport for all and widespread participation in organised physical activities has significantly declined.8 The aim of this article is to contribute to the broader discussion on sport-related policy development by presenting key stakeholders, their evolution over time, and the contemporary challenges.

Despite some earlier work, it can be concluded that there is limited research within the Central and Southeastern European region on sport-related policymaking and understanding the sport ecosystem.9,10 That being said, it is necessary to point to tectonic changes following the aftermath of the 1990s in the context of the dissolution of the one-party system characterised by rigid communist practices, especially within the Soviet bloc. The departure from this socio-political system proved to be equally necessary and challenging within the geopolitical context of integration with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). According to Péter,11 the overall transitional shocks in Romania not only led to socio-economical struggles but also shaped the sport ecosystem and its relationships within. However, the extent and consistency of these changes remain yet to be explored. This is not just unique to the Romanian context, as in other post-communist (post-socialist) countries the results are rather symbolised in a never-ending transition.12,13 The rise of corruptive practices is omnipresent, regardless of an attempt to weaken the state or political grip over sport, as these remain rather formal or nominal orientation.14,15 The growing lack of resources and the exclusive status of particular organizations have significantly derogated the overall performance of Romanian sports, whereas privatization of reputable sport organizations has mostly been directed and shaped to favour closely constructed informal networks.16 Another joint determinant represents the importance of sport for often non-sporting objectives inclusive of reshaping national identities or acting as a polarizing force both internally and externally.17 In this context, the sport ecosystem is an extension of the public sector or is influenced by its culture, relying on strong institutional memory regardless of socio-political changes and instability.18

2. SPORT HISTORY, POLICY, AND GOVERNANCE

Sport regulatory regimes have a strong tradition established reflecting different eras and socio-political realms. The broader concept of physical education has been the subject of legislative frameworks under three types of political regimes experienced by the Romanian state and were imbued with their values. These political regimes were represented by the monarchist regime (1881–1947), the communist regime (1947–1989), and the post-communist democratic regime (1989–present). During these periods, physical education and sport evolved at different paces, both organizationally and conceptually, while maintaining institutional stability within the last two periods, as both the peaks and regression of this evolution are intertwined with the tectonic political shifts of the 1990s.

In 1912, Prince Ferdinand I founded the Romanian Sport Societies Federation (Federaţia Societăţilor Sportive Române), which had the role of governing Romanian sport as an attempt to centralised patrimonial effort over growing public activity. The federation consisted of 12 sports commissions, each with a jurisdiction primarily focused on militaristic readiness.19 The first two Physical Education laws in Romania enacted in 1923 and 1929, were adopted by the monarchical regime. The Physical Education Law of 1923 stipulated that "physical education is a general obligation," for all young people prior to military service.20 This law regulated jurisdictions and competencies of the newly established organization, the National Physical Education Office (NPEO), which served as a central policy and administrative body under the Ministry of Education. Following the horizontal coordination efforts, the Ministry of Education maintained administrative relations with the Ministry of War and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Social Protection. The publication of the first law coincided with the creation of the National Institute of Physical Education (NIPE) in Bucharest, the first institution dedicated to training specialists in the field. The law from 1929, in an operational sense represents a continuation of the same approach adding a number of amendments aimed at introducing sports and tourism in addition to physical education as activities specific to the field.21 This law turned physical education into an "obligation for all the youth of the country," to be carried out in both private or state educational institutions and in other specialised organizations. This law regulated the establishment of the Union of Sports Federations of Romania (USFR) as the main organiser of sports activity in Romania, which was subordinated to the Ministry of Public Instruction, National Defence, and Health, Labor, and Social Protection. However, the economic and socio-political context soon brought another change to the Law of 1929, namely regulating the professionalization of athletes. Football professionalization was incorporated but lasted less than 20 years, until the end of the Second World War.22 Leadership-wise, during the interwar period, sport was led by members of the bourgeoisie or monarchy. For example, King Carol of Romania was the president of the Romanian Olympic Committee (1923–1940).

With the change of the regime in 1946, the Popular Sports Organization was established under Law No. 135/1946 with the aim of organizing and controlling sports and physical education in Romania. This organization functioned until 1949 when the Committee for Physical Culture and Sport (CPCS) was established through Decree No. 329/1949. In 1957, the physical culture and sport movement was led by the Union for Physical Culture and Sport (UPCS) as a result of the reorganization of the field inspired by the Soviet model. The old organization (CPCS) was considered overly bureaucratic and overly focused on sports performance, without considering the mass aspect of physical education and the sport for all concept. During communism, only one major law, Law No. 29/1967, was enacted to guide the development of physical education and sports, as there was the intention to focus on policies rather than legislative framework. The purpose of this law was the development of physical education and sports which was aligned with the decisions of the National Conference of the Sports Movement on 28–29 July, 1967.23 The law also served as a pretext for leadership changes in sports and physical education, contributing to centralised policymaking.24 Thus, the UPCS was changed into the National Council for Physical Education and Sport (NCPES) becoming the central leading organization, which was locally represented by the County Councils for Physical Education and Sport (CCPES). The law stipulated that "physical education and sports in the Socialist Republic of Romania constituted activities of national interest." This transformed the entire field into a major priority for reaching often non-sporting objectives and it benefited from major investments in infrastructure, professional training for specialists, and the development of a large number of athletes. High-performance sports were prioritised to encourage national unity, and the results of Romanian sports at major international events justified further centralization efforts. Consequently, the term mass sport was introduced with the aim of encouraging widespread participation by as many Romanians as possible in order not only to strengthen health, but to enable sustainability of wider political efforts. It was notion that healthy citizens contributed to the growth and development of industry and agriculture, as well as national defense.25 For this purpose, by mimicking the leader of the communist bloc, the system followed the Soviet approach and model of physical culture (including workers’ sport), whereas workplace gymnastics, training gymnastics, and gymnastics minutes were introduced in mass sports initiatives.26 As sports expanded across multiple sectors, the NCPES collaborated with other government institutions, such as the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of the Armed Forces, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Besides these ministries, collaboration included ones that operated outside of the traditional public sector, but very strong political or quasi-political organizations, such as the General Union of Trade Unions, the Union of Communist Youth, and the National Union of Handicraft Cooperatives. Consequently, sport was mainly led by politicians, with field specialists occupying secondary roles, such as vice presidents. The Committee for Physical Culture and Sport was chaired by Manole Bodnăraş (1952–1957), a politician and brother of Emil Bodnăraş, vice-president of the Council of Ministers of the Romanian People's Republic. The Union for Physical Culture and Sport was led among others by General Marin Dragnea (1974–1984). Generally, presidents of national sports organization were also presidents of the Romanian Olympic Committee. Among the field specialists who held leadership positions were university professors such as Leon Teodorescu (vice president) and Ioan Kunst Ghermănescu (secretary) from the Institute of Physical Education and Sport in Bucharest. Lia Manoliu, a former Olympic champion, served as vice president of the NCPES and COR (1982–1989).27

Starting in 1990 with the decline of communism and the transition from a totalitarian regime to a democratic one, the NCPES was abolished. Following the major socio-political shifts, the sport was managed by the newly created Ministry of Sport, as decided by the Prime Minister. However, due to institutional instability under the ongoing transition, frequent changes occurred within the government structure. The ministry coordinated youth affairs and was renamed the Ministry of Youth and Sports accordingly.28 Operationally, the successor to the NCPES, despite wider transitions, did not alter public service culture, aside from adding or reproducing administration at the local level. The ministry was represented by County Directorates for Youth and Sports. The new ministry set objectives focused on maintenance of citizens' health by developing programs aligned with the sports for all concept. At the same time, efforts were made to balance this approach with high-performance sports as an attempt to recreate the sporting successes during the communist era. In order to maintain this balance, the Ministry of Youth and Sports collaborated mainly with the Ministry of Education regarding the organization of school and university sports, but also with the Ministry of Health. The last Law on Physical Education, adopted in 2000, reaffirmed the strategic orientation of sport and physical education as activities of national interest. Additionally, it also confirmed the state’s supervision and support and the continuation of governmentalisation of sports.29 The Romanian case is not unique per se, as many post-communist or post-socialist countries experienced similar pathways inclusive of governmentalization and politicization of sport.30,31

Furthermore, activities associated with sport and physical education are defined as all forms of physical activity intended, through organised or independent participation, to express or improve physical condition and spiritual comfort. Moreover, it emphasized societal value of sport in the effort to establish civilised social relations along with the reference to providing conditions for the development of high-performance sports. However, the scope of these activities remains broad by involving school-related physical activities (such as physical education, school sports, and university sports), recreational sports, sports for all, high-performance sports, and other physical and leisure activities used for health maintenance, prophylactic, or therapeutic purposes. Nominally, the law stipulates that the practice of physical education and sports represent a basic human right, without any discrimination, and guaranteed by the state. This is an attempt to depart from the previous positioning of sports as militaristic or ideological tool.32 The role of physical education and sport has evolved greatly: from a general obligation under the monarchist government, to an activity of national interest under the communist government, to a fundamental right under the current government. Ideologically, sport evolved from an activity specific only to certain social classes, to one imposed upon everyone, and to every citizen’s right in present time. However, in practice this right remains hard to be fulfilled due to a number of challenges. These include a lack of appropriate policies (e.g. for sports for all), and the predominant orientation of sports organizations towards competitive and high-performance sports.

In 2004, Romania joined the European Community, requiring the pre-accession measures to be taken. Among these was the restructuring of the government and its ministries. Thus, the Ministry of Youth and Sports became the National Agency for Sports.33 This functioned until 2008 when it was reestablished as the Ministry of Youth and Sports.34 The change to revert to a ministry was triggered by the drastic decrease in the number of medals won at the Olympic Games in Beijing (nine medals in total) compared to the Olympic Games in Athens (19 medals). The leading politicians believed that reestablishing the ministry would strengthen the sports system while preventing the decline. In 2010, a new government reshuffle brought sports under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Research and Sport, with the establishment of the National Authority for Sport and Youth within this ministry.35 It remained active until 2013, when the Ministry of Youth and Sports was reestablished.36 In 2022, the ministry became the Ministry of Sports. For the first time, sport was run autonomously, but this autonomy was short-lived.37 In June 2023, the Ministry of Sport transformed again into the National Agency for Sport.38

Institutional stability reflected dominant political presence of major stakeholders within Romanian sports ecosystem. After the communist government changed, only former Olympic champions, such as Lia Manoliu, Ion Ţiriac, and Mihai Covaliu were elected to lead the COR. Similarly, various politicians lead the Ministry of Sport or the National Sports Agency. Among them were also sports specialists, including coaches like Octavian Belu and Mariana Bitang, Olympic champions like Elisabeta Lipă, and Paralympic champions like Eduard Novak. Octavian Belu and Mariana Bitang were the only leaders without political affiliation, while the rest were members of political parties. Currently, Elisabeta Lipa, a multiple Olympic champion in rowing, is the president of the National Agency for Sport (ANS).

2.1. ROMANIAN SPORT ECOSYSTEM

The National Agency for Sport (Agentia Nationala pentru Sport) is the administrative authority responsible for organising and controlling sports in Romania. At the local level, this role is represented by the County Sports Directorates, which include 41 County Directorates for Sport, plus the Directorate for Sport of the Municipality of Bucharest. Their role is the implementation of the NAS strategies and programs. It is subordinated to 70 sports federations, which in turn manage 9,102 affiliated sports clubs and 7,621 sports clubs participating in the national competitive system.39 Performance sport has had a representative role for Romania in the competitions organised by different international sports forums. Performance athletes are classified as either amateur or professionals, according to the statutes and regulations of national and international sports federations. Six sports branches are recognized as professional in Romania: football, handball, basketball, rugby, volleyball, and boxing. The sports structures in Romania are made up of sports associations, county sports associations, and sports clubs.40

Within the Ministry of Education, there are educational units with sport programs, such as high schools with sports programs, as well as palaces and clubs for children and students. These palaces are remnants of the communist era. The first Palace of Pioneers was established in Bucharest in 1950 and later replicated throughout the country in various cities and municipalities. Currently, they have been renamed as Children's Palaces, and they organize extracurricular activities in different fields including arts, culture, and sports, all funded by the state. Certain technical sports that could not be found in other sports clubs are practiced here, such as karting or ship modelling. Only a few of these institutions organise these activities.41

At the national level in Romania, professional leagues, sports federations, and other sports organizations can be found. Sports organizations are private law associations or public law institutions and can be affiliated either with county associations, in order to participate in competitions organised at the local level, or with sports federations, in order to participate in national and international competitions.

NAS collaborates with the Romanian Olympic and Sports Committee (COSR) in financing and running programs for the preparation and participation of Romanian athletes in the Olympic Games, as well as in promoting the values of Olympism. The Romanian Olympic and Sports Committee is an association of national interest that operates in accordance with its own statute, drawn up in line with the provisions of the Olympic Charter and national laws. It was founded in 1914 and operated under the name of the Romanian Olympic Committee until 2004, when it adopted the name Romanian Olympic and Sports Committee. Its role includes managing high-performance Olympic sports and creating the representative team of Romania that participates in the Olympic Games. The name changes in 2004, which followed the French model, was intended to strengthen COSR’s influence in the governance of high-performance sports and to increase funding for athletes. However, this was not achieved. Sports federations were still financed by the ministry, particularly through the national agency. At an international level, COSR is affiliated with the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Throughout its history, COSR has had four IOC members for Romania. George Gh. Bibescu (1899–1901) and George Alexandru Plagino (1908–1949) were IOC members during the monarchy of the country, and Alexandru Siperco (1955–1998) during the communist period the immediate post-communist era. Currently, Octavian Morariu has been an IOC member for Romania since 2013.42

After 1990, in addition to the state-governed organizations, private law-based clubs, and sports associations appeared, as well as some professional sports branches organised into leagues. The sport structure, up to that point, consisted of amateur and professional sports, and those financed by the state or the private sector. New forms of sports practice emerged. They were organised under structures affiliated with national and international organizations. These are sports for people with special needs, school and university sports, and sports for all. These new forms existed in the communist period; however, they were established into federations after 1990.

Sports for people with special needs was stipulated in the sports Law 69/2000. Even though the World Deaf Games were held in Bucharest in 1977 and Alex Peer was the first athlete to represent Romania at the Paralympic Games in 1972 in Heidelberg in the table tennis event, performance sport was represented at the federation level only after 1990. This was the year the Romanian Sports Federation for the Handicapped was founded, which operated under the Sports for All Directorate. The adoption of Law 69/2000 transformed all sports federations, including FRSH, into legal entities under private law with public utility status. With this new law, the federation’s name was also changed to the Romanian Sports Federation for Disabled Persons. In 2009, following amendments to the Physical Education and Sports Law No. 69/ 2000, it became the Romanian Paralympic Committee (RPC).43

Within the RPC, there are three subcommittees that represent the sports activities of people with visual impairment, motor disabilities, and intellectual disabilities. Even though the number of sports clubs and sports disciplines for athletes with disabilities is increasing in Romania, sports for people with special needs remain a field at the beginning of its development. Romania officially began participating in the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta with a delegation of several athletes. The most numerous delegation was in 2016, in Rio, with 11 athletes. A total of six medals have been won, one of which was gold won by Eduard Novak in paracycling at the 2012 London Games.44

This Paralympic medal created a debate on the discrimination faced by Paralympic athletes. In Romania, the government allocates cash prizes to athletes who win medals at the Olympic Games. In 2012, the government did not include Paralympic athletes in the prize regulations because it did not allocate a budget for the participation of the Romanian team in the Paralympic Games. The Romanian Paralympic Committee had to find sponsorships to ensure the participation of the Paralympic athletes. From 2012 onward, when the government started awarding prizes to athletes who won medals at the Olympic Games, they remembered to include Paralympic athletes. However, Paralympic sports and the National Paralympic Committee continuously receive less funding than the Romanian Olympic Committee or the National Sports Agency.45

The Strategy for Sport for People with Special Needs established for the period 2016–2032 provides for the increase in the number of people with special needs who systematically practice sports in order to maintain their health, social inclusion, and participate in sports competitions.46 The measures to ensure such growth include the increase in the number of sports clubs where people with disabilities can practice sports and physical activities, the increase in the number of members of these clubs, informing the population and people with disabilities about the benefits of practicing sports and the professional specialty training for coaches, instructors and referees so that they can train and organise activities for athletes with disabilities.47

Physical education and pre-university and university sports are organised by the Ministry of Education. Sports activities within the pre-university and university system take place within the sports associations that are affiliated with the Federation of School and University Sports (FSUS), founded in 1996 under Decision 1239/1996.48 Until 1989, school and university sports clubs were largely financed by the Ministry of Education, without the support of a sports federation. University sports clubs participated in national championships with other sports clubs, such as Steaua Bucharest (Sports Club of the Army), Dinamo Bucharest (Sports Club of the Ministry of the Interior), and were financed by other ministries, and other municipal sports clubs funded by enterprises and factories (e.g. Rapid Bucharest, Clubul Căilor Ferate Române, etc.).

For that reason, university sports in Romania even if funded, did not develop a system specific to the university environment (Petracovschi & Gombos, 2022). They rather focused on strengthening the Romanian competitive system, with a goal of producing highly trained athletes for the participating national teams in international competitions during the Cold War.49 School sports clubs were the main training grounds for performance athletes up to the age of 18. Once the junior period was completed, they transferred to another university, labour, army, or militia sports clubs. Currently, there is the Federation of School and University Sports (FSUS) which is affiliated with the International Federation of School Sports (IFSS). The representatives of these clubs participate in international high school competitions for students aged 6 to 18. FSUS is also affiliated with the European University Sports Association (EUSA) and the Federation Internationale du Sport Universitaire (FISU).

Sports students participated in European championships or World University Games, obtaining significant results in both individual and collective sports. Remarkably, in 1981, Bucharest hosted the 11th edition of the World University Games, which was one of the major sporting events ever organised in Romania. In 2016, the Romanian national team won the title of World University Champion in men's handball. However, all the players on the team were professional athletes in the men's handball championship of Romania, reflecting the communist era.50

Sport for All was organised by the Romanian Sport for All Federation (FRSPT), which was founded in 1992. During the communist period, it was called mass sport, but in the 1980s, this new term was introduced at a European level, representing a new concept. Whereas mass sport placed importance on the participation of large groups of people and its role in education, sport for all focused on the individual and the importance of each person to practice sport and physical activity.51 According to Law 69/2000, FRSPT was reorganised in 2002 and became a legal entity under private law, classified as a public utility, non-governmental, non-political, and non-profit organisation with branches in all counties and in Bucharest. These county associations collaborated with the County Directorates. At an international level, it has been affiliated with the International Federation Sport for All (IFSA) since 1992, the Association for International Sport for All (TAFISA) since 1993, and the International Sport and Culture Association (ISCA) since 2011.52

3. SPORT FUNDING SYSTEM IN ROMANIA

The most important aspect in developing any policy is financing, therefore Romanian sport system has struggled with the lack of financial resources, whether in top-level sports or in Sport for All area. In 2010, Octavian Morariu, a COSR President, declared that “sports must get a maximum 25 % from the public budget,” with the remaining funds coming from the private sector including National Lottery, betting, and broadcasting. Moreover, politicians should create a legislative environment to encourage the private sector to allocate financial support to sports, not only through taxes, but also through direct sponsorship.53 Unfortunately, Romanian sports rely on public funding even today because there has not been a political decision in favour of sports.

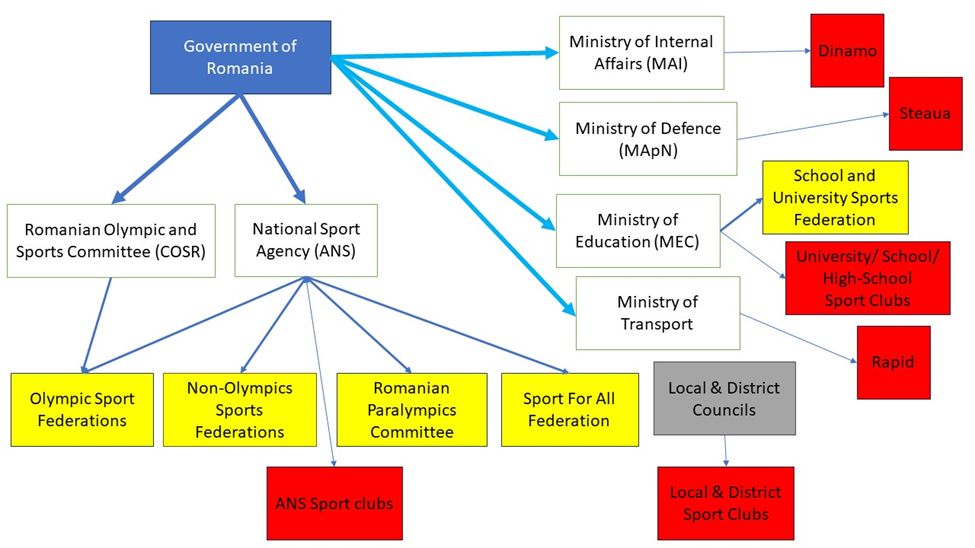

In 2015, the Romanian Government allocated 0.05% of GDP to sports.54 Moreover, this percentage remained consistent (around 0.05%), despite the target being 1% of GDP. This study will focus on the public funding from the government and local authorities to the sports federations and clubs as illustrated in Figure 1.

There are two types of financial support from the central authorities. The one is direct funding from the government to sports institutions, and the second is from the government to a certain number of sports clubs, which fall under the jurisdiction of different Ministers. For instance, the Ministry of Internal Affairs is in charge of Dinamo Bucharest, while the Ministry of Transport is financing Rapid Bucharest. Steaua Bucharest is one of the four sports clubs and the most famous one which gets financial support from the Ministry of Defence. Steaua and Dinamo are the clubs from the communist period still offering their athletes military ranks and promotion on the military scale based on sports performance. The Ministry of Education is in charge of School and University Sports Federation (FSSU) and university/ school / high-school sports clubs. FSSU organizes sports competitions for all age groups, from primary school to university, in different sports. A total of 230 sports clubs are directly financed by the Ministry of Education. At the same time, local and district councils finance 346 local sports clubs. All the data referenced in the study refers to the year 2020.55

Figure 1: Romanian Sports Funding System

The Government of Romania is in charge of the budget for the Romanian Olympic and Sports Committee (COSR) and the National Agency for Sport providing them with direct financing. COSR is in charge of the Olympic Sports Federations with a special focus on top-level athletes who are a part of the Olympic Team. It provides financial support for their preparations at the 11 National Sports Centers, managed by the National Sports Agency, and participation in different competitions.56

The National Sports Agency (NAS) distributes its budget to the Sports for All Federation, the Romanian Paralympics Committee, 33 non-Olympic sports federations, and 31 Olympic sports federations. Starting in 2024, there was a major change in the financing system. NAS and COSR have decided to finance with larger budgets the federations with a higher likelihood of winning medals at the Paris 2024 Olympics, contrary to the past custom where all sports federations, —Olympic and non-Olympic—received more or less equal funding. Therefore, Rowing, Box and Table Tennis Federations received the most significant budgets in 2024.57 It is worth mentioning that the three federations are not financed from the public budget. The Ice-hockey and Tennis federations have legal issues with their rules and regulations, which prevent them from applying for funding. The Football Federation has opted not to apply. Moreover, there are additionally 48 sports clubs that are under NAS’s jurisdiction and are financed directly by the agency.58

Compared to most European countries. where the National Lottery is active in financing sports, the Romanian National Lottery only claims to be an active financial contributor in the sports field, without providing any data. There is hardly any data regarding the percentage or amount of money allocated to sports, except for football. According to Romanian law 69/2000, the National Lottery is supposed to pay 20% of its football betting revenues to the Romanian Football Federation.59

3.1. SERVICE PROVIDERS IN SPORTS: PRIVATE COMPANIES, SPONSORSHIP, AND BROADCASTING

As previously mentioned, there are six professional sports in Romania: football, handball, rugby, basketball, volleyball, and boxing. Notably, five out of six are team sports, with boxing being the only individual sport. It is common that professional sports are financially sustained by the private sector, as they are seen as businesses and are supposed to bring profit to the clubs. However, this is not the case in Romania, where private companies are hardly involved in sports because they do not receive any economic benefits from investing in sports. Multinational companies invest in some sporting events as part of their corporate social responsibility policy, such as the Raiffeisen Bank – Bucharest Marathon.

Broadcasting rights are important for the vast majority of professional sports clubs. There are available data on this subject only for football, handball, and basketball, whereas volleyball, rugby, and boxing most likely do not get any money from broadcasting. Rugby is broadcast on the Romanian national channel (TVR 2), but volleyball and boxing can rarely be watched on TV. The men's basketball league received for the 2022–2023 season 150,000 euros in broadcasting rights, with certain clubs receiving 6,000–13,000 euros.60 Popa analysed the budgets of the top teams in the National Men’s Basketball League (LNBM) and concluded that highest budget was around 1.1 million euros for CSM CSU Oradea, while the lowest was around 120,000 euros for CSM Sighetul Marmaţiei. CSM CSU Oradea had 37 private sector partners at the time, which covered between 75 – 80 % of the budget. A similar situation occurred at CSU Sibiu, where 65-70 % of the 800,000 euros budget was financed by private companies.61

The situation is somewhat better in handball in terms of TV rights. In 2015, the Handball Federation sold the TV rights for both the men’s and women’s leagues for 300,000 euros.62 In 2016, there was an increase of € 100,000, whereas, TV rights were sold for € 500,000 per season for the 2022–2023 season.63 The situation is surprising given that Liga Florilor Mol (the Women’s National League) is considered one of the most competitive and attractive leagues in the world. Players’ salaries range from 15,000 to 20,000 euros per month, while the budgets of the biggest teams are around 4 million euros. Around 53 foreign players who competed in the Romanian league participated in the last World Cup. The surprise is that all 14 teams are public teams with no private clubs. Most of the budgets come from public money. Twelve teams belong to local and municipal authorities, while two clubs get financed from ministries.64 A journalistic investigation that compared the club budgets of women's handball clubs in Romania and Hungary revealed the difference between the financing sources. For instance, Gyori ETO KC, a famous team that has won the Women’s Handball Champions League four times, receives 4 million euros from its main sponsor (Audi), another 1 million from smaller sponsors, club merchandising, and TV rights, plus 1 million euros from public authorities. In contrast, HC Dunărea Brăila, a team with no participation in European competitions, has a 4-million-euro budget entirely supported by public funds, the city and district authorities. Moreover, the Hungarian club makes a profit every year, turning its handball club into a profitable business.65

The most important sport in financial terms is football, as the top league and the second league attract TV stations. The Romanian FA is in charge of selling the TV rights for Liga 2 (the Second League). For the 2017–2018 season, TV stations paid 380,000 euros and 500,000 euros for the 2018–2019 season for the rights. Liga 2 gained popularity and this reflected in the rising value of TV rights. The amount increased by 50,000 euros every season, reaching 750,000 euros for the 2023–2024 season.66 The Romanian top league (Superliga) is managed by the Romanian Professional League (LPF). The LPF receives 28.5 million euros per season for the 16 clubs participating in the competition 28,5. The lowest amount received by a club is 970,000 euros per season, while the championship winner receives approximately 2.6 million euros.67

As previously mentioned, there are not relevant data regarding the amounts received by sport organizations from the National lottery or betting companies. At the same time, it is evident that, mainly concerning football, betting companies are the main sponsors not only for the clubs but also for football bodies. The two top leagues, the Romanian Cup, and ten clubs from the top league are sponsored by different betting companies. Football financing and club ownership are subject for future research, particularly since it is common for local authorities or ministries to own clubs, especially in Liga 2.

The only professional boxing gala, known as Gala Bute, was organised by the Romanian Boxing Federation in cooperation with the Ministry of Development and Tourism in 2011. Unfortunately, the event ended in an important corruption scandal. The key decision-makers including the Romanian Boxing Federation President, the Minister of Development and Tourism, and other civil servants were sentenced to prison for economic fraud.68

In conclusion, the public authorities remain the main sponsors of Romanian sports, whether at the central, local, or district level. Sport is controlled and highly influenced by politics, thus the sportive achievements are still awaited, as decision-makers are more interested in saving their positions rather than taking decision in the benefit of sport in general and athletes more specifically.

4. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES IN THE FIELD OF SPORTS

Romanian sports have been characterised by inconsistent and incoherent decision-making. Between 1990 and 2020, there were at least 23 ministers leading the Ministry of Sports. Only two ministers held a mandate for more than three years, while three served between two and three years. Eleven ministers lead the institution for one to two years, and seven were in charge for less than a year. On average, the ministers’ mandates in the period between 2000 and 2020 did not exceed 18 months.69 Moreover, the lack of a coherent public policy regarding sports was more visible in 2023, when on 24 May, 2023, the Romanian Government approved the National Strategy for Sport 2023–2032 in the Monitorul Oficial. Less than a month later, on 16 June, 2023, the Romanian Government decided to abolish the Ministry of Sports, replacing it with the National Agency for Sports. The National Agency for Sports is led by a President with a rank of State Secretary, who is subordinate to the General Secretariat of the Government. In contrast, when the Ministry of Sports existed, its minister was a member of the Romanian Government.

In the post-communist history, sports have not been a priority for the Romanian governments. Even though the White Charter of European Sports was signed in 2005 in Lisbon, Romania’s first national strategy for sports appeared after more than 10 years, in 2016. Moreover, the White Charter of European Sports outlined a "European sports model” which had to be implemented through legislation by each government. However, Romanian authorities ignored it, disregarding the indications of good practices at the continental level. In 2016, Romania adopted its first sports policy document named National Strategy Plan for Sport and Youth in Romania (2016–2032).70 This first document served as an x-ray of the disastrous state of Romanian sports rather than a detailed action plan. While various specific actions were proposed, there was no implementation plan for the said proposed projects.

In 2022, the Romanian Government, through the General Secretariat of the Government, publish the Institutional Strategic Plan for Minister of Sport 2022–2025.71 This is the first official sports policy document with a clear structure providing the main priorities and the planning, implementation, and follow-up for each proposed project. Six strategic objectives were settled: (1) Sport for all, (2) Top-level sport, (3) Rediscover Oina, (4) Generation 28, (5) Top-level sport events in Romania, (6) Developing sports infrastructure. Sport for all project focused on increasing the number of Romanians who would engage in sports for health reasons. Top-level sport was designed to increase the elite athletes’ participation and performances in major competitions such as Olympics, World Cups, and European Championships. Rediscover Oina (Romanian Baseball) aimed to raise awareness of the national sport among the younger generation. Generation 28 targeted citizens with disabilities with the goal of doubling the athletes’ number in Romania and organising dedicated competitions for them. Top-level sport events in Romania focused on the involvement of sport federations and central authorities in hosting major sport events, such as European Championships or World Cups There is a connection between the sport events and the final strategic objective, as the organization of major events also requires the development of sports infrastructure, such as stadiums and multifunctional sports halls, which must fulfil certain requirements.

Unfortunately, in less than a year, instead of implementing the Institutional Strategic Plan, the Romanian Government published the National Strategy Plan for Sport in Romania 2023–2032. As previously mentioned, the same politicians decide to dissolve the Ministry of Sport and transform it in the National Agency for Sports. The institutional inconsistency was also discussed by Octavian Morariu, former COSR president, already in 2010. He claimed that the Romanian sports crisis would not be solved by the administrative restructuring, but by new laws that encourage private sector to invest in sports, with the main focus on the athlete. He finds it irrelevant whether sports belong to a ministry or an agency, as long as there is a clear and consistent sports policy implemented by governmental institutions (Chiriac 2010).72

4.1. THE NOVAK LAW AND THE CHALLENGES OF SPORT IN ROMANIA

Eduard Novak, the former minister of sports, required that all sports teams participating in national competitions ensure that at least 40% of their athletes be Romanian, both at senior and youth levels. This decision was made due to challenges faced by Romanian performance sports, especially in team sports.73 Before 1989, Romanian athletes could only transfer to foreign teams with the consent of the government. This consent was rarely granted and implied drastic regulations. After 1990, Romanian athletes could freely search for work contracts abroad. For those who chose to, the main reason was the higher financial value of employment contracts. Fast forward to the present time, many male and female athletes choose to play in the Romanian national leagues, as the employment contracts are more profitable than those in their countries or other European countries. This is evident for women’s handball in Romania where club teams employ foreign professional athletes to the detriment of Romanian athletes. While this strengthens the national championship and the teams' performance in European competitions, national teams do not show any results at an international level, such as in the Olympic Games, World, and European Championships. The law aims to stop the arrival of foreign athletes in Romania, but this order conflicts with the right to free movement of athletes within the European Union (Art. 45 TFEU). These teams are financed by the state budget because they are mainly supported by town halls. Examples are the Bucharest Municipal Sports Club and the 2018 Bistriţa-Năsăud Sports Club. Confronted with the challenge of poor sports results worldwide, the NAS is currently trying to implement another policy that was introduced by Minister Eduard Novak. Politically speaking, Minister Novak, representing the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, shared the vision of Viktor Orban, the Hungary’s Prime Minister regarding sports. Just like Hungary, which has prioritised investment in six sports since 2010, it is desired to allocate the NAS budget to sports branches with the greatest potential for obtaining a medal at the Olympic Games. Prior to this regulation, the budget was distributed equally among all 65 sports federations.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In political terms, Romanian sport remains anchored in the past, but there are also elements that show that efforts are being made to develop a general framework that would allow the creation of a system capable of producing results and obtaining sports medals. The hierarchy of sports federations that produced results in the past has changed, as these federations managed to adapt to a new performance model. They serve as examples of how much a model could be extended to other federations and to the entire sports system in Romania. If the change cannot occur from the top down, it is possible that a bottom-up action is more effective. Nevertheless, when sports policies are concerned, many aspects need to be improved, adapted or changed.

Bibliography

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 994 din 3 septembrie 1990 privind organizarea şi functionarea Ministerului Tineretului şi Sportului”. Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/1228.

Government of Romania. “Hotararea nr. 924 din 12 septembrie 2012 pentru modificarea şi completarea Normelor financiare pentru activitatea sportivă, aprobate prin Hotărârea Guvernului nr. 1447/2007. Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/141365.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 759 din 3 iulie 2003 privind organizarea şi funcţionarea Agenţiei Naţionale pentru Sport”. Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/44877.

Government of Romania, “HOTĂRÂRE nr. 1.239 din 20 noiembrie 1996 privind înfiinţarea, organizarea şi funcţionarea Federaţiei Sportului Şcolar şi Universitar”, Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/10306.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 1721 din 30 decembrie 2008 privind organizarea şi funcţionarea Ministerului Tineretului şi Sportului.” Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/101299.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 141 din 23 februarie 2010 privind înfiinţarea, organizarea şi funcţionarea Autorităţii Naţionale pentru Sport şi Tineret.” Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/116710.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 11 din 9 ianuarie 2013 privind organizarea și funcționarea Ministerului Tineretului și Sportului.” Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/144782.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 25 din 5 ianuarie 2022 privind organizarea și funcționarea Ministerului Sportului”. Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/250279.

Government of Romania, “Hotararea nr. 576 din 7 iulie 2023privind organizarea, funcționarea și atribuțiile Agenției Naționale pentru Sport.” Accessed on November 26, 2024.https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/272007.