Introduction

Tropical root and tuber crops, of which cassava, sweet potato and cocoyam are important representatives, constitute a part of the under exploited resources of developing countries. Many of the developing world‘s poorest farmers and food insecure people are highly dependent on root and tuber crops as a source of food and cash income (Scott et al., 2000). The principal component of these tropical root and tuber crops is starch, which is increasingly becoming an important raw material for the food and non- food industries worldwide. Despite the fact that tropical root and tuber crops are rich in starch, they remain underutilized in the food industry, even though starch from these crops could be used in different industrial applications (Wickramasinghe, 2009). The current industrial demand for starch is being met by a restricted number of crops, mainly corn, potato, and wheat (Ellis et al., 1998). Consequently, the world starch market is dominated by starches from these three crops. In order to increase the competitiveness of starches from tropical root and tuber crops on the world markets, unveiling of the characteristic properties of starches from other crops is required (FAO, 1998). Starch is one of the most important products in the world. It is an essential component of food, providing a large proportion of daily calorie intake for both humans and livestock. Starch alone accounts for 60-70% of calorie intake of humans (Lawton, 2004). Besides its nutritive value, starch is a very versatile raw material with a wide range of applications in food, feed, pharmaceutical, textile, paper, cosmetic and construction industries. In the food industry, starch is used as a thickener, filler contributing to the solid content of soups, a binder to consolidate the mass of food and prevent it from drying out during cooking, and as a stabilizer (Eke-Ejiofor, 2015). Non-food applications of starch include: adhesives in the paper and packaging industry, match-head binders in explosives, concrete block binders and plywood adhesive in the construction industry, fabric finishing and printing in the textile industry, pill coating and dispersing agents in pharmaceuticals, sintered metal adhesive and foundry core binders in metals, and manufacture of biodegradable plastics and dry cell batteries (Ellis et al., 1998;FAO, 1998;Moorthy, 2002;Burrell, 2003;Lawton, 2004).These applications depend on the functional properties of the starches such as gelatinization, pasting, retrogradation, water absorption capacity, swelling power and solubility, which vary considerably from one botanical source to another. Till now, the characteristic properties of starches from tuber crops in Nigeria, such as cocoyam, have been limited. This lack of knowledge has limited the use of starch from these crops in various industrial applications. If these crops are to be considered as new sources of starch for the Nigerian industry, their physicochemical, functional and structural properties need to be investigated and evaluated. Such knowledge would uncover the opportunities offered by these root crops and facilitate the utilization of starches from these crops in the industry. Furthermore, a detailed knowledge of the characteristics of these starches would enable tailoring of their properties by physical and/or chemical modification and help Nigeria to compete effectively on the markets. In the long run, utilization of these starches will save foreign currency, create employment opportunities and bring economic benefit to the local Nigerians. Therefore, this study is aimed at evaluating the physicochemical properties of food grade acetylated cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) starches.

Materials and methods

Materials

Matured red fleshed cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) was obtained from Osiele market, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Other processing materials used were a knife, a bucket, trays, foil paper, polyethylene bags and muslin cloth. Laboratory chemicals and reagents used include: Acetic anhydride, sodium hydroxide, sodium hydrogen carbonate, hydrochloric acid and other chemicals, which were obtained from Jaybees Laboratory Stores, Abeokuta, Nigeria.

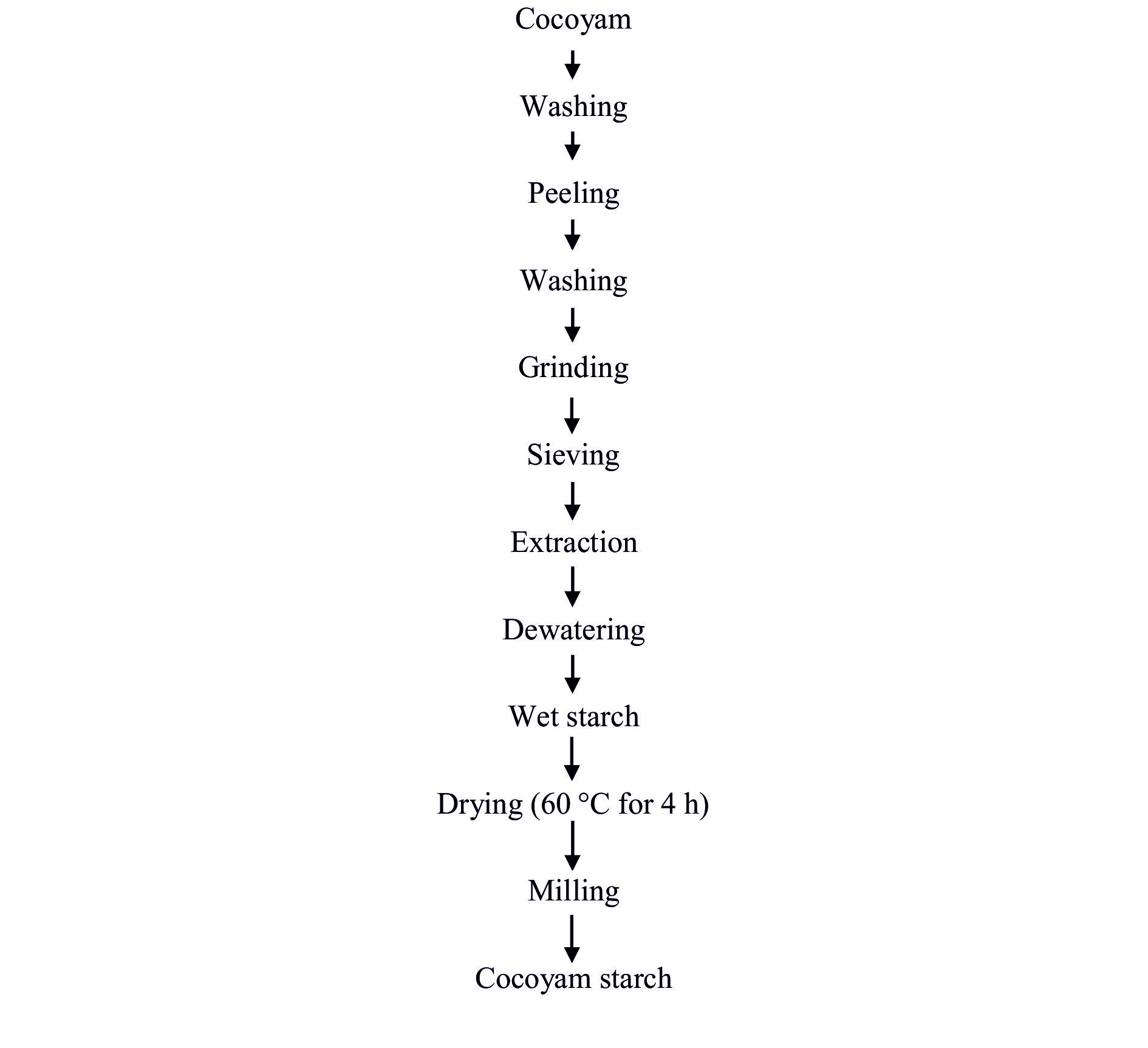

Extraction of starch from cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium)

The method described byOsunsami et al. (1989) with slight modifications was used for the extraction of cocoyam starch. The cocoyam tubers were harvested and washed to remove soil and dirt from the skin and then peeled using a kitchen knife. The peeled roots were washed, grated and sieved by washing off in a basin of water. The mixture was filtered through a fine mesh sieve (Muslin cloth). The filtrate was allowed to settle, after which the supernatant was decanted and sediment was collectedin order to obtain the wet starch. The cocoyam wet starch was spread in the cabinet dryer at 60 °C for 4 h. It was later cooled, thoroughly milled with a Phillips blender (model HR-1702) and packaged in polythene bags at ambient temperature (26±2 °C) and atmospheric pressure until further analysis.

Acetylation of the starch

The method bySathe and Salunkhe (1981) was used for the acetylation of the starch. The starch sample (100 g) was dispersed in 500 ml of distilled water and stirred magnetically for 20 min. The pH of the obtained slurry was adjusted to 8.0 using 1.0 M NaOH. Acetic anhydride (10.2 g) was added slowly to the mixture while maintaining a pH range of 8.0 to 8.5. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 5 min after the addition of acetic anhydride. The pH of the slurry was finally adjusted to 4.5 using 0.5 M HCl. It was then filtered, washed four times with distilled water and dried in the air oven at 45±2 °C for 48 h.

Determination of the degree of acetylation of the starches

Samples (5 g) of the acetylated starches were weighed into a 250 ml flask and 50 ml of distilled water was added. A few drops of phenolphthalein indicator were added and the starch suspension was titrated with 0.1 M NaOH solution to a permanent pink end-point, after which 25 ml of 0.45 M NaOH were added. The mixture was sealed tightly with a rubber stopper and shaken vigorously for 30 min. After 30 min the stopper was removed and the starch was washed down from the walls of the container with distilled water. The slurry was subsequently titrated with 0.2 M HCl solution until the disappearance of the pink colour. Native starch was treated in a similar manner for blank determination. The degree of acetylation and substitution was determined using equations 1 and 2.

Chemical and functional properties of acetylated starch

Moisture content determination

Moisture content was determined using the method described byA.O.A.C (2000).

Measurement of pH

The method described byDaramola and Adegoke (2007) was used. The pH was determined using a digital pH meter. Standardization of the pH meter was carried out using buffer solutions of pH 9 and 4. A 5 g sample was dispersed in 25 ml of distilled water and the mixture was subjected to stirring until an equilibrium pH was obtained, after which the pH was measured.

Paste clarity

Paste clarity was determined according toCeballos et al. (2007). A 1% aqueous solution of starch was boiled at 93 °C with repeated shaking for 30 min. The solution was transferred into a cuvette after cooling and transmittance was then measured at 650 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Swelling power and solubility index

This was determined using the method described byTakashi and Sieb (1988). It involved weighing 1g of sample into a 50 ml centrifuge tube, after which 50 ml of distilled water was added and mixed gently. The slurry was heated in a water bath at 90 ºC for 15 min. During heating, the slurry was stirred gently to prevent clumping of the starch. After15 min, the paste inside the tubes was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min using a centrifuge (GALLENKOMP, England, 90-1). The supernatant was decanted immediately after centrifuging. The weight of the sediment was taken and recorded. The moisture content of the sedimented gel was thereafter dried in an air oven dryer at 50 °C for 10 h to get the dry matter content of the gel. The swelling power and the solubility index of the starch were calculated using equations 3 and 4 respectively.

Pasting properties of acetylated starch

Pasting properties were determined with a Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA TECMASTER, Perten Instrument) using the method reported byAdebowale et al. (2005). Three grams (3 g) of sample were weighed into a dried empty canister and then 25 ml of distilled water was dispensed into the canister containing the sample. The suspension was thoroughly and properly mixed so that no lumps remained and the canister was fitted into the rapid visco analyzer. A paddle was then placed into the canister and the test proceeded immediately, automatically plotting the characteristic curve. Parameters estimated were peak viscosity, setback viscosity, final viscosity, trough, breakdown viscosity, pasting temperature and time to reach peak time.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained were subjected to statistical analysis. Means, Analysis of variance (ANOVA), were determined using a SPSS Version 21.0 and the differences between the mean values were evaluated at p<0.05 using Duncan’s multiple range test.

Results and discussion

The degrees of acetylation and substitution of cocoyam starches are presented in Table 1. The range of values for the degree of acetylation and substitution was 2.1 to 2.4 and 0.080 to 0.090 respectively. Acetylated starch is usually used in food applications owing to its paste stability and clarity (Aning, 2012). The result obtained for the degree of acetylation in this study was very close to the range of 2.5% acetyl content recommended by the Food and Drug Administration for acetylation (Rutenberg and Solarek, 1984;Thomas and Atwell, 1999). Therefore, the acetyl content of the acetylated starches is within the prescribed limit, making them suitable for use in food products.

| Samples | Degree of acetylatoin (%) | Degree of substitution (DS) |

|---|---|---|

| NaOH acetylated cocoyam starch | 2.10 | 0.080 |

| NaHCO3 acetylated cocoyam starch | 2.40 | 0.090 |

Chemical and functional properties of acetylated starch

The chemical and functional properties of acetylated starch are shown in Table 2. There was a significant (<0.05) difference in the moisture content of the starch samples. The moisture content ranged from 9.57 to 12.67% with native cocoyam starch having the lowest moisture content, while cocoyam starch acetylated with NaHCO3 had the highest moisture content. It was noted that there was a decrease in moisture content after the acetylation, which could be the result of the methods used for drying and the drying conditions of the starch (Shildreck and Smith, 1967;Daramola and Adegoke, 2007). The pH of the starch ranged between 5.20 and 6.40. Native cocoyam starch had the highest pH, while cocoyam starch acetylated with NaOH had the lowest pH. The decrease in the pH of the starch after the acetylation might be due to the carboxylic group from hydrates of acetic anhydride that may have been substituted in the position of the hydroxyl moiety of glucose units in the native starch polymer (Daramola and Adejoke, 2007). The pH obtained in this study was higher than in the findings ofDaramola and Adejoke (2007) on acetylation of breadfruit starches. This might due to the extraction method used for the starch and the type of reagents involved in the acetylation process (Wilkins et al., 2003).

The paste clarity ranged between 16.30 and 31.60, where cocoyam starch acetylated with NaOH had the highest value compared with the native starch and the cocoyam starch acetylated with NaHCO3. The highest paste clarity found in cocoyam starch acetylated with NaOH might be due to the esterification of starch acetates.arowenko (1986)J reported that acetyl groups disrupt interactions betweenthe outer chain of amylopectin and the linear chain of starch polymer. The highest paste clarity of starch obtained in this study may be useful for application in food and textile industries where high clarity is required(Jyothi et al., 2007), while the lower paste clarity of starch obtained in this study may find useful application in gravies and thickened food where low transparency is expected (Nuwamanya et al., 2011).

The swelling power and the solubility index are usually used to assess the extent of interaction between starch chains within the amorphous and crystalline domains of the starch granule (Ratnayake et al., 2002). The swelling power and the solubility index of the cocoyam starches ranged from 2.73 to 6.87 gg-1 and 0.93 to 4.83% respectively, where the native cocoyam starch had the lowest and cocoyam starch acetylated with NaHCO3 the highest value. The increase in the swelling power and the solubility index could be a result of the granule size and amylose content of the cocoyam starches (Cisse et al., 2013). Indeed, starch with large granules swells rapidly when heated in water and water molecules are bonded to the free hydroxyl groups of amylose and amylopectin by hydrogen bonds (Singh et al., 2003).

Pasting properties of native and acetylated cocoyam starches

The pasting properties of native and acetylated cocoyam starches are shown in Table 3. There was significant (p<0.05) difference in the trough, breakdown, final and setback viscosities of cocoyam starches. Peak viscosity is the highest viscosity achieved during cooking of flour pastes. It is the maximum viscosity developed by a starch-water suspension during heating (Adebowale et al., 2005). The peak viscosity ranged from 215.50 to 256.96 RVU, where the native cocoyam starches had the lowest, while cocoyam starches acetylated with NaHCO3 had the highest value. The result obtained for peak viscosity was similar to the findings ofAgboola et al. (1986), who also reported an increase in peak viscosity of acetylated cassava starch. High peak viscosity of acetylated cocoyam starch obtained in this study might be linked to the weakened granule integrity caused by the substitute of acetyl groups in starch polymer (Perez-sira and Gonzalez–Parada, 1997). The trough viscosity is indicative of the additional breakdown of granules due to stirring, reflecting and stability of the hot paste. It providesa measure of the tendency of the paste to break down during cooking (Normita and Cruz, 2002). The trough viscosity ranged between 134.92 RVU and 153.92 RVU. Cocoyam starch acetylated with NaOH had the highest trough viscosity, while the native cocoyam starch had the lowest. The higher trough viscosity indicates the greater ability of the paste to withstand breakdown during cooling. The breakdown viscosity value is an index of the stability of starch (Fernande and Berry, 1989). The breakdown viscosity ranges from 80.71 to 102.46 RVU. Breakdown viscosity measures the ability of paste to withstand breakdown during cooling.

Final viscosity is the most commonly used parameter to determine a particular starch-base sample quality (Sanni et al., 2006). It also indicates the ability to form paste or gel after cooling (Ikegwu et al., 2010). Final viscosity ranged from 244.90 to 244.13 RVU, where the native cocoyam starch had the lowest and cocoyam starch acetylated with NaOH the highest value. The variation observed in the final viscosity in this study might be due to the sample kinetic effect of cooling on viscosity and the re-association of starch molecules in the samples (Nwokeke et al., 2013). The setback values ranged from 105.88 to 112.79 RVU. Setback is a measure of the stability of paste after cooking. It is a phase during cooling of the mixture, where a re-association between the starch molecules occurs to a greater or lesser degree. Consequently, it affects retrogradation or reordering of starch molecules, which is associated with syneresis and weeping (Sanni et al., 2004). Therefore, the starch samples with relatively high setback viscosity obtained in this study might probably exhibit a higher retrogradation tendency (Bolade and Adeyemi, 2012). The peak time ranged between 4.47 and 4.60 min, where the native cocoyam starch had the highest values, which suggests more processing time, and cocoyam starch acetylated with NaHCO3 had the lowest values. The pasting temperature gives an indication of the gelatinization time during processing. It is the temperature at which the first detectable increase in viscosity is measured and it is an index characterized by the initial change due to the swelling of starch (Eniola and Delarosa, 1981y). The pasting temperature ranged from 82.90 to 83.88 °C. Native cocoyam starch had the highest pasting temperature which indicates that the starch from the native cocoyam is highly resistant to swelling during cooking. A higher pasting temperature implies higher water binding capacity and higher gelatinization (Numfor et al., 1996).

Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that starch produced from cocoyam can be altered through acetylation. The acetylation improves the pasting properties, swelling power, solubility and paste clarity of the modified cocoyam starches. Therefore it can be concluded that acetylated cocoyam starch produced under thes conditions may be used as an alternative food grade starch additive for industrial purposes, thereby encouraging import substitution.