INTRODUCTION

To date, the concept of loyalty in the field of tourism and hospitality still represents a source of new ideas in scientific research. The growing interest in loyalty research, however, has not been paralleled by innovation in research methodology. Some authors warn that research structures that are very similar in a conceptual and methodological sense tend to yield similar research results (Zhang et al. 2014;McKercher et al. 2012;Tribe 2006). With an uninventive way of doing research, there is a great possibility of losing sight of important changes in practice. An example of this are trends which clearly show that loyalty to a single business is continuously losing its identity, although numerous authors continue to focus on loyalty taking into consideration only a single hospitality business.

According to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991), most human social behaviour, including purchasing behaviour, can be predicted based on repeat patronage intention. Such information, however, cannot be collected using data mining tools nor can it be retrieved from a database, so field research is extremely important when it comes to understanding behavioural intentions. From a conceptual viewpoint, there are two main approaches to the study of loyalty: the behavioural approach and the attitudinal approach (San Martin et al. 2013). Attitudinal loyalty can be described as having favourable feelings towards a destination or brand (Verma and Rajendran 2017), with focus on future actions (Zins 2001), while behavioural or action loyalty refers to a concrete number of (re)visits or (re)purchases. Previous research has made several distinctions between the two approaches. For instance, while satisfaction is seen as an important precondition of attitudinal loyalty, it may have different effects on action loyalty (behavioural approach).Lee et al. (2012), point out that many tourists may be unable to revisit a foreign destination even if they are highly satisfied with their experience. Furthermore, to date, behavioural loyalty has referred to only one meaning, while attitudinal loyalty has been equated with many different concepts, such as attachment (Yoo et al. 2018), commitment (Kim et al. 2014) intention to recommend (Han et al. 2017) and involvement (McIntyre 1989). Many researchers have also suggested that attitudinal loyalty has a direct effect on behavioural loyalty (e.g. switching resistance loyalty (Lee and Hyun 2016) and that frequent visitors are more willing to recommend and repurchase a brand (Shoemaker and Lewis 1999).

Since the measurement of loyalty in tourism is particularly difficult (Oppermann 2000), there is a strong need to create a distinction between loyalty in tourism and hospitality, and loyalty in other businesses. Some of the core differences are the necessity for deeper relationships, small transactional numbers and large amounts of personal data. Guests or tourists do not create relationships with destinations or hospitality enterprises based on their transactional contacts. Thus, tourist arrival numbers alone are not a reliable indicator of loyalty that could ultimately be expected to lead to building loyalty. Although the composite approach, as an integration of both approaches (attitudinal and behavioural), seems to be the most comprehensive (Mechinda et al. 2009), it is still unclear if it is the best approach to be used in a tourism or hospitality context.

With regard to research interest, the primary objectives of this study are to: (1) provide insights into research design/methods employed in loyalty research; (2) offer an overview of different loyalty types, modes of expressions; (3) provide an overview of locations where loyalty research was done; and (4) synthetize research issues emerging from previous research and having strong development potential in the future.

This article is divided into five main interconnected sections. The aim of the first section is to present the methodological steps of content analysis. In the second section, the topic of loyalty is analysed through research interest, with focus on publication years, research clusters and research location. Then in the third section, we synthetize the most researched common loyalty types and modes of expression, in order to provide a conceptual framework within loyalty research in the tourism and hospitality business. After examination of the results, we discuss findings and present managerial implications and suggestions for further research.

1. METHODOLOGY

Given the growing number of studies, a systematic literature review is required in order to deduct general conclusions of past research and to provide concise recommendations and directions for future research. Accordingly, this review has followed the general requirements for systematic review papers, suggested byFurunes 2019.

The central idea of content analysis is that many words of a text are classified into much fewer content categories (Weber 1990) in order to create a systematic overview of the analysed data. To perform the analysis, the prerequisite was to select the data and the level of analysis. The research was done on the Web of Science platform (database Web of Science Core Collection), which provides comprehensive coverage of the most important journals in Social Sciences.

Conference articles, conference reports, book reviews, abstracts, editor prefaces, Internet columns and book chapters were excluded from this study, given their limited contribution to knowledge development about loyalty research. Since this is the first content analysis of tourism loyalty research from a broader perspective, prior clusters could not be applied.

After targeting the database, all three authors participated in content analysis that was performed in three main phases. (1) Data screening of titles was done based on the general keywords “tourism loyalty” OR “destination loyalty” OR “hotel loyalty”. From the initial search, 288 articles emerged. (2) To keep the focus on tourism and hospitality, the results were refined and only articles in the category “hospitality leisure and sport” with SSCI (Social Science Citation Index) were retained (n=112). (3) After a topical review, the authors analysed the content of the papers. Out of 112 articles, 97 articles with primary research data were identified as relevant for further analysis.

2. TOPICAL REVIEW

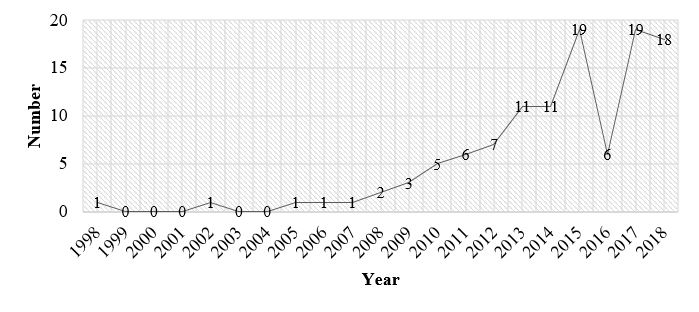

In the past two decades, the topic of loyalty has been present in numerous journals in the field of social sciences (economics) and has seen a distinctly positive growth trend in recent years.Figure 1 summarises the articles about loyalty published in the Web of Science Core Collection (WOSCC) database.

Source: Web of Science (webofknowledge.com)

The results inFigure 1 indicate a steady growth in research interest, with the exception of the year 2016, and imply that this upward trend could continue into the future.

Of the 20 scientific journals that have published papers on loyalty research in the field of tourism and hospitality, the Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing accounts for the majority of papers published (16.1%).Table 1 provides an overview of the journals.

Source: Web of Science

Following the analytical framework for content analysis (Schuckert et al. 2015), this paper reviews articles in terms of topical focus, target industry, research area and methodology applied. To create a framework for classifying and analysing previous research, the authors used four clusters – topics, which were most commonly used in loyalty research in the field of tourism and hospitality:

(multi) destination loyalty (46 papers)

hotel (brand) loyalty (32 papers)

loyalty programme (14 papers)

event (festival) loyalty (5 papers).

With regard to the locations where loyalty research was conducted, Asia accounted for 48% of all research, followed by the USA accounting for 25.7%, Europe for 16.5%, Australia for 5.2%, and Africa for 4.1%. Loyalty research locations are presented inTable 2. The majority of research was done on site, and only 7.2% of data were collected through online questionnaires, mostly in the USA.

Source: Web of Science

3. LOYALTY TAXONOMIES

Loyalty expressed through loyalty behaviour, although probably being the most precise loyalty measurement (Buttle and Burton 2002), is often complemented in social sciences with other manners of expressing loyalty. In order to retrieve the motivational background, research issues have been broadened to encompass research questions such as the intention to recommend, intention to repeat behaviour, and intention to pay a higher price. Their common denominator is attitudinal loyalty (Table 3).

WOM (Kim 2018); Cognitive (Yuksel et al. 2010); Conative (Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil 2018) Affective loyalty (Lee et al. 2012)

One of the most cited authors in the researched loyalty literature (n= 49 articles) is Oliver, who defines loyalty as a deeply held commitment to continue using products or services consistently in the future, despite influences having the potential to cause switching behaviour. His widely accepted definition suggests that the loyalty concept needs to be evaluated from both aspects, (1) behavioural, through a focus on past activities, and (2) attitudinal, to understand and predict future actions (Oliver 1997). Despite the fact that Oliver’s research focuses on consumers rather than on tourists or guests, many authors in the tourism and hospitality literature have embraced his viewpoint. Some of them areChen and Gursoy (2001), who point out that the combination of behavioural loyalty and attitudinal loyalty more robustly reflects destination loyalty.

Among the broadly accepted loyalty schemes in tourism research are the “loyalty phases”, also introduced byOliver (1999) as cognitive, affective, conative and action loyalty. Oliver’s logic of the concept points out that attitudinal loyalty should be observed as a sequential process in which loyalty is first expressed in a cognitive sense, then in an affective sense, and finally in a connotation sense. Attitudinal loyalty first manifests itself according to the valorisation of received benefits (intellectual level). Then, with repeat patronage a special feeling of connection with the brand, destination or preferred type of holiday occurs (emotional level). The next level is reflected in the positive intention for future cooperation (connotation loyalty) and, lastly, in the action control sequence, intention to revisit is transformed into action.

Using the framework of Oliver’s loyalty phases, researchers have drawn many conclusions. For example,Han et al. (2008) pointed out that cognitively loyal guests are willing to pay a higher price for received benefits compared with other loyalty dimensions.Pedersen and Nysveen (2001) concluded that cognitive loyalty is the weakest mode of loyalty expression compared with conative or affective expression.

Yuksel et al. (2010) describe the cognitive dimension of loyalty through the recognition of the value derived from repeated behaviour compared with other choices. Cognitive loyalty is visible through guest evaluation of received benefits and expenses in the moment when they decide to ignore all the price differences for their preferred brand. Based on the available information about benefits and expenses, guests can evaluate their overall interest that represents motivation for repeat patronage. The base for evaluation is usually the price, which guests pay for received benefits. Hence, to measure cognitive loyalty, the authors used statements such as: “Increase in prices will not influence my loyalty to the brand; lower competition prices will not influence my buying behaviour towards a preferred brand”.

Given that emotions stimulate the human brain more than the intellect does, the emotional level of loyalty is seen as important in predicting future loyal behaviour although emotions cannot guarantee that a guest will return to a specific destination. To ensure emotionally loyal guests who will return, it is necessary to develop a relationship of trust with the guests (Evanschitzky et al. 2012), especially in an affective way (Kandampully et al. 2015). The affective dimension of loyalty has been manifested through variables such as: “I am passionate about destination XY”, “Destination induces a great delight for me” and “I have formed an emotional attachment to destination XY”.

According toAlmeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil (2018), connotation or conative loyalty as the next loyalty phase represents loyalty in the phase before repeated arrival, stated through intention and willingness for repeated behaviour. To express connotation loyalty or intention for future relations with service providers, the authors use statements like: “I am willing to revisit destination XY in the future”, “I plan to revisit destination XY in the future”, and “I will make an effort to revisit destination XY in the future”.

Despite using different modes of expression, it may be concluded that previous loyalty phases have one common characteristic, seen as strong commitment to a preferred destination or brand. Thus, it seems reasonable that researchers use commitment as a synonym for attitudinal loyalty. Examples of this are “calculative commitment” (Bansal et al. 2004), “emotional –affective commitment” (Tanford et al. 2011) and “continuance commitment” (Kim et al. 2014).

Although loyalty phases are widely accepted, this research reveals that authors in tourism and hospitality research have rarely used the phases in their full context. In fact, in most of the research (n= 77 articles) conative loyalty expression was used in combination with intention to recommend. This finding may raise the question of integrity in loyalty research, especially when authors use only two items to test loyalty in a research model.

Namely, according toHair et al. (2010), when specifying the number of indicators per construct, it is recommended to avoid constructs with fewer than three indicators. However, this research confirms the presence of loyalty variables with two items (Sato et al. 2018;Masiero et al. 2018;Martínez González et al. 2017;Yi et al. 2017;Mody et al. 2017;Folgado-Fernández et al. 2017;Lo et al. 2017;Sreejesh and Ponnam 2017;Antón et al. 2017;Nam et al. 2016;Qiu et al. 2015;Yang and Lau 2015;Chang and Gibson 2015;Lee et al. 2014;Forgas-Coll et al. 2012;Kim et al. 2011;Song et al. 2013;Geng-Qing Chi and Qu 2008;McDowall 2010;Chi and Qu 2008;Kim 2008;Yoon and Uysal 2005;Tsaur et al. 2002).

Having in mind all the ways in which loyalty can be expressed, it is justified to assume that important loyalty considerations are missing, which should have been included in the studies to reveal true loyalty intentions and relationships between variables. The absence of a sufficient number (three and more) of manifest loyalty variables may lead the researcher to misleading or erroneous conclusions about loyalty, especially when loyalty represents the logical end of a research model.

3.1. Destination loyalty

Destination loyalty emerges in situations when tourists are likely to revisit a preferred destination several times repeatedly, independently of the type of accommodation. Most authors use either likelihood to recommend or repeat visit intention to define destination loyalty. Regardless of the loyalty expression, destination loyalty can be analysed through direct and indirect variables used in research. Structural equation modelling (SEM) seems to be the most appropriate method to analyse research results in this topic. Thus, the authors have created an analytical overview of all supported variables connected to loyalty constructs and tested using SEM (Table 4).

| Indirectly connected variables | Directly connected variables |

| Memorable Tourism Experiences through Destination image (Kim 2018) |

Overall satisfaction (Kim 2018;Sato et al. 2018;Lin and Huang 2018,Chen and Rahman 2018;Martínez González et al. 2017;Campón-Cerro and Hernández-Mogollón 2017;Sangpikul 2017;Su et al. 2017;Verma and Rajendran 2017;Yolal et al. 2017;Antón et al. 2014;Lee et al. 2014;Sun et al. 2013;Chen and Phou 2013;Forgas-Coll et al. 2012;Prayag and Ryan 2012;Chi 2011;Chen and Myagmarsuren 2010;Chi and Qu 2008;Kim 2008;Lee et al. 2007*;Yoon and Uysal 2005) Attribute satisfaction (Chi 2012), Satisfaction with tourism experiences (da Costa Mendes et al. 2010) |

| Pull motivations (culture and rafting services) through Satisfaction (Sato et al. 2018) | Destination image (Kim 2018;Folgado-Fernández et al. 2017;Chung and Chen 2018;Campón-Cerro et al. 2017;Bianchi and Pike 2011) |

| Perceived value through Satisfaction (Hallak et al. 2017) | Rafting services (Sato et al. 2018) |

| Performances of wellness spa tourism, through positive and negative affective experiences (Han et al. 2017) | Memorable tourism experiences, Affective experience (Han et al. 2017;Yuksel et al. 2010;Kim 2018) |

| Positive affective experiences and negative affective experiences through overall Satisfaction (Han et al. 2017) | Customer-based brand equity (Wong 2018) |

| Natural soundscape image through Satisfaction (Jiang et al. 2018) | Emotional attachment (Martínez González et al. 2017;Prayag and Ryan 2012) |

| Country image through tourism destination image (Chung and Chen 2018) | Intrapersonal Authenticity (Yi et al. 2017) |

| Customer-Based Brand Equity through Abstract Attributes (Wong 2018) | Quality (Campón-Cerro et al. 2017;Kim et al. 2012) |

|

Service Fairness through Satisfaction (Su et al. 2017) | Value (Campón-Cerro et al. 2017;Verma and Rajendran 2017;Kim et al. 2012;Forgas-Coll et al. 2012), Emotional value (Lin and Huang 2018) |

|

Destination image through satisfaction (Kim et al. 2012;Su et al. 2017;Song et al. 2013; (Prayag and Ryan 2012);Geng-Qing Chii and Qu 2008)

| Event loyalty (Folgado-Fernández et al. 2017) |

| Quality through satisfaction (Yolal et al. 2017;Kim et al. 2012;Su et al. 2017) | Event brand (Folgado-Fernández et al. 2017) |

| Quality through trust (Su et al. 2017) | Trust (Su et al. 2017;Chen and Phou 2013) |

| Indirectly connected variables | Directly connected variables |

|

Destination trust through Destination Brand Identification (Kumar and Kaushik 2017) | (Destination) Identity (Kumar and Kaushik 2017;Yuksel et al. 2010) |

| Historical nostalgic experience through perceived value and Satisfaction (Verma and Rajendran 2017) | Historical nostalgic experience (Verma and Rajendran 2017) |

| Perceived destination ability (Lee and Hyun 2016) | Passionate love, Self-Brand Integration, Switching resistance Loyalty (Lee and Hyun 2016) |

| Satisfaction through destination trust (Song et al. 2013) |

Destination distinctiveness, Personal connection to local people (Nam et al. 2016) |

| Destination image through Perceived value (Song et al. 2013) | Attractiveness (Vigolo 2015) |

| Satisfaction through past experience (negative) (San Martin et al. 2013) | Positive emotions (Lee et al. 2014) |

| Destination Attachment through Satisfaction (Yuksel et al. 2010) | Booking services, e-forums and virtual tours (Neuts et al. 2013) |

| Attribute satisfaction through Overall Satisfaction(Chi and Qu 2008) | Past experience, situationalinvolvement (San Martin et al. 2013) |

| Satisfaction through Attitudinal and Conative Loyalty (for behavioural loyalty) (Lee et al. 2007) |

Affective loyalty (on conative loyalty) (Forgas-Coll et al. 2012;Yuksel et al. 2010) Cognitive loyalty (on affective loyalty) (Yuksel et al. 2010) Attitudinal loyalty (on conative loyalty) (Lee et al. 2007) Conative loyalty (on behavioral loyalty) (Lee et al. 2007) |

| Service quality through activity involvement and satisfaction (Lee et al. 2007) | Self-congruity, functional, hedonic, leisure, and safety congruity (Bosnjak et al. 2011) |

| Destination brand salience (Bianchi and Pike 2011) | |

| Place dependence (on cognitive loyalty) (Yuksel et al. 2010) | |

| Push motivation (Yoon and Uysal 2005) |

* supported only on conative and affective loyalty

Source: authors

This study confirms the previous recognition that satisfaction is a key antecedent of destination loyalty statements (Chen and Myagmarsuren 2010). Besides the importance of satisfaction in direct connection with loyalty constructs, the analysis shows that satisfaction is also the most common mediator between destination loyalty and various constructs in research models.

Loyalty as an endogenous variable in path analysis could be affected through other variables with direct or indirect effect. Indirect effect represents the influence of the independent variable on a dependent variable including mediation of one or more variables (Raspor 2012), while direct effect could be explained as a simple causal relationship excluding the effects of mediators or moderators. With respect to destination loyalty research (Table 4), it could be concluded that loyalty research does not lack in inspirations with direct and indirect relationships between the different explored variables. However, when it comes to the number of units/destinations researched, most studies focus on a single destination, implying a lack of conceptual and methodological innovation (Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil 2018). Moreover, in most cases, loyalty is used as a dependent final variable of the research model and only in rare situations (n=6 articles) do authors use loyalty as a mediator between constructs.

The consequences of pressure due to growing competition among destinations, together with changes in tourist behaviour, have spurred important changes in the overall picture of the tourism market. These changes are reflected in a larger number of holidays, albeit shorter ones per individual, and in the unstoppable growth of the number of destinations in the market and the development of their offerings (Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil 2018). Simultaneously this has affected loyalty behaviour and created the need to test destination loyalty together with other loyalty types and modes of expression. In previous research, when guests did not see themselves as being loyal to a brand or a destination, they were considered disloyal guests and no further analysis was performed in that case.McKercher et al. (2012) are among the few authors who researched experiential loyalty as a new aspect of loyalty to a destination. According to their research, three experiential loyalty patterns were evident: (1) a dominant, preferred destination, with substantial variety-seeking shown in one-off visits to other destinations, (2) once-off or infrequent repeat visits (less than once every five years) and (3) loyalty to several holiday styles (two or three preferred holiday styles, different destinations to satisfy these styles). The question that arises is: If there are significant changes in loyalty behaviour, and if loyalty to a specific holiday style, regardless of the destination, brand or hotel really exists, is loyalty the right name to call that phenomenon?

3.2. Loyalty/ frequency programmes

The concept of hotel loyalty is directly related to a company’s profitability (Palacios-Florencio et al. 2018). Profitability as basic intention encompasses the plethora of other perspectives incomparable to destination or event loyalty. Years after the implementation of loyalty programmes, the need to redefine the term “loyalty” has emerged, due to acknowledging that the number of arrivals is not an indication of brand commitment (Henning-Thurau et al. 2002.), Polygamous loyalty (Dowling and Uncles 1997) or multi-brand loyalty (Felix 2014) are considered phenomena in development, driven by the growth in the number of loyalty programmes in which the guest’s attention redirects from one to multiple brands. Authors highlight some of the reasons for the spreading of multi-brand loyalty, such as a low level of recognition in combination with more options and a low level of risk with brand change (Bennett and Rundle-Thiele 2005). According toFelix (2014), an important motivation for consumers to be multi-brand loyal is the desire to maintain behavioural freedom while reducing the negative emotional effects of choice overload. With companies imitating each other’s loyalty schemes and given the rapid expansion of loyalty cards in almost all lines of business, it is no surprise that polygamous loyalty was inevitable in the hospitality business as well. Namely,Kim et al. (2014) warn of the large number of loyalty programmes in the hotel industry and the possibility that guests are likely to participate in several hotel loyalty programmes at the same time. To provide a better understanding of the differences between brand loyalty and polygamous loyalty (loyalty to a programme),Laškarin (2013) uses two different terms: frequency programme (frequent flyer programme) and loyalty programme.

The key difference between these two loyalty programmes is visible in the research subject and the methods used to analyse guest data. In the development of CRM programmes, the history card represents the predecessor of contemporary loyalty programmes, and its main purpose was to facilitate the management of relationships with guests. Loyalty programmes have to focus on value for the guest, respecting at the same time the value of the guest for the company. Numerous authors (e.g.,Hua et al. 2018;Xie and Chen 2014;Lee et al. 2015), have studied the effectiveness of loyalty programmes in encouraging loyal behaviour, and questions arise as to whether loyalty programmes really work (Steinhoff and Palmatier 2014) and what makes the difference between successful loyalty programmes and unsuccessful ones. The authors have identified the three most common objectives of the research papers (table 5).

| Objectives | Findings |

| To investigate the role/effect of loyalty programme membership on hotel loyalty |

Psychological value of loyalty programme is important predictor of active loyalty (Xie and Chen 2014); Higher-tier reward members are more emotionally attached than lower-tier members; Reward members are less likely to switch compared to non-members (Tanford et al. 2011) Two core attributes of programme effectiveness: emotional commitment and reward programme evaluation (Tanford 2013) Programme benefits do not affect the quality of the relationship between member and hotel brand (Lo and Im 2014) A well designed and implemented loyalty program with integrated social responsibility can create trust as well a strong long term relationship with customers (Nemec Rudež 2010) Switching costs are more effective than programme value in driving active loyalty to a brand (Xie et al. 2015) Benefits of the loyalty programme and partnerships with other brands (non-hotel) positively influence (through member tier and satisfaction) brand loyalty (Yoo et al. 2018) |

| To investigate the role/effect of loyalty programme membership on programme loyalty |

Economic rewards drive programme loyalty more significantly than social rewards (Lee et al. 2015) Flexibility of the loyalty programme is a crucial factor between polygamous programme loyalty and loyalty to one programme, e.g. members will stay in only one programme if they perceive flexibility (Xiong et al. 2014) |

| To investigate impact of hotel loyalty programme on hotel operations | Loyalty programme expenses are positively connected with RevPar, ADR, Occupancy and GOP (Hua et al. 2018). |

3.3. Hotel/Brand loyalty

According to analysis, guests who express commitment through behaviour or attitude in an affective, cognitive or conative manner are considered as being loyal to a hotel or hotel brand. Some authors (Bowen and Shoemaker 2003;Tanford et al. 2012) emphasize affective commitment as a key factor in maintaining relationships with guests in the hotel industry; without emotional attachment there is little or no chance to succeed in winning back former guests. As with other types of loyalty, SEM is the most commonly applied methodology in the field of hotel (brand) loyalty research. The analysis of hotel brand loyalty literature shows that in 28 articles (out of 32) the authors used SEM as the main methodology to test hypotheses in their research.Table 6 shows all supported directly and indirectly connected variables used in hotel/brand loyalty research.

| Indirectly connected variables | Directly connected variables |

|

Hotel practices of waste reduction management (through Hedonic and Utilitarian value)Han et al. (2018a) Guests’ intention to participate in green hotel practices (Han et al. 2018a) |

Hedonic value, Utilitarian value, Extent ofparticipation (Han et al. 2018a) Perceived value (So et al. 2013) Relationship commitment (Han et al. 2018b) |

| Consumer motives (functional, socio psychological, hedonistic, corporate identification) (Ben-Shaul and Reichel 2018) |

Degree of active contribution (knowledge creation) |

| Corporate Social Responsibility (partially supported) (Palacios-Florencio et al. 2018) | Corporate social responsibility (Palacios-Florencio et al. 2018) |

| Direct symbolic value (Yoo et al. 2018) | Status (Yoo et al. 2018) |

| Customer orientation (Yang et al. 2017) |

Satisfaction (Yoo et al. 2018;Han et al. 2018b;Yang et al. 2017;Qiu et al. 2015;Kim et al. 2014;Jani and Han 2014) e-satisfaction (Kim et al. 2011) e-trust (Kim et al. 2011) Relationship satisfaction (Christou 2010) Satisfaction with service recovery (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara et al. 2014) |

| Personality factors - Agreeableness, neuroticism (through satisfaction and hotel image)Jani and Han (2014) |

Affective Brand Image, CognitiveBrand (Mody et al. 2017) Hotel Image (Jani and Han 2014) |

|

Satisfaction (through hotel image)Jani and Han (2014) Brand satisfaction (through relationship commitment)Han et al. (2018b) | NovelValue Dimension, Utilitarian Dimension, Experiential Dimension (Tsai 2017) |

| Perceived fit between a hotel’s core business and green practices (through perception of hotel green practices)Ham and Han (2013) |

Company Identification (Yang et al. 2017) Brand Experience (Hussein 2018) |

| Costumer Brand Identification (through customer brand evaluation)So et al. (2013) | A good experience of website purchasingbehavior (Abou-Shouk and Khalifa 2017) |

| Brand experiences (through customer satisfaction)Hussein (2018) |

Brand Relationship Quality (Lo et al. 2017) Service Quality (So et al. 2013) |

| Pleasure (through brand satisfaction and relationship commitment)Han et al. (2018b) |

Service Brand Evaluation (So et al. 2016)), Brand Trust (Kim et al. 2015;García de Leaniz and Rodríguez Del Bosque Rodríguez 2015;So et al. 2013) Customer Engagement (So et al. 2016) |

| Relationship marketing knowledge level of hotel customers (Lin and Huang 2018) | |

| Site attachment, Altruism (Kim et al. 2015) | |

| Relationshipequity, Brand equity (Liu et al. 2015) | |

| Relationship investment, (Qiu et al. 2015) Switching Costs (Kim et al. 2011) | |

| Identification with company, Commitment (García de Leaniz and Rodríguez Del Bosque Rodríguez 2015) | |

| Perception of hotel Green Practice (Ham and Han 2013) |

3.4. Event loyalty

The analysis based on research articles disclosed two types of events: cultural (literary, gastronomic, agricultural) and sport tourism events. Among the analysed articles, event loyalty is measured through revisit behaviour (3), willingness to recommend (3) and resistance to change (1). The authors tested event loyalty through SEM and revealed its important role as a mediating variable (Kim et al. 2018;Folgado-Fernández et al. 2017), and dependent variable (Kirkup and Sutherland 2017). When it comes to cultural events, events fostering experiences on an emotional level can be very successful in enhancing destination attachment and predicting destination loyalty.Folgado-Fernández et al. (2017) suggest that not only large events have the power to develop and enhance destination image but that well-organized small events can also produce equally good results. Satisfied visitors at a festival evolve an emotional attachment to a festival host destination and ultimately become loyal to that destination (Lee et al. 2012).

Unlike cultural events, sport events are analysed in order to understand loyalty to sport events (without its mediation on destination loyalty). One of the ideas of participation in sport events, introduced byOkayasu et al. (2010), is that participation is a product of the resources invested between event organizers and participants, where resource exchanges lead to loyalty from participants.

4. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATION

The entire tourism system is interconnected and heavily dependent on various contact points. In that system, satisfaction has been viewed as a collective benefit where all shareholders are in a win-win situation. Loyalty, from the other perspective in that process, represents a step further, going beyond the framework of the common good, and those who participate in creating value for guests want that “piece of the cake” only for themselves. Following the Pareto Principle or the 80/20 Rule, it is more important for a hotel to have a database of loyal guests who are loyal exclusively to that hotel. Therefore, it is still unclear if multi-brand loyalty is the type of loyalty that hospitality companies are willing to accept.

In line with this perspective, loyalty research at the level of a single hotel is directly or indirectly motivated by the need to understand a company's financial benefit, while loyalty issues at the level of single or multiple destinations are fuelled by benefits to society. Experiential loyalty, as the potential type of loyalty, goes outside the framework of direct benefits for tourism and hospitality activities, with loyalty research aiming to understand individuals and the benefits they gain. Although the direct benefit coming from this type of loyalty is minimal, it should not be neglected that this is information that could better explain changes in the behaviour of modern tourists. In order to understand the broader importance of loyal guests, taking into account indirect and immediate benefits for society in general, research needs to be raised to a higher level by including a greater number of respondents and focusing on a greater number of destinations.

Several implications for marketing managers of hotel companies and for destination management organizations can be drawn from the conducted research. First, based on research it is important to segment hotel guests based on different loyalty types, as this will help to distinguish between different types of hotel guests and to prepare tailor-made offers for them. Second, loyalty programmes are easily imitated and therefore marketing managers in hotels should not focus on the constant improvement of loyalty programmes but rather on finding and promoting distinct value propositions on an emotional level that is important for encouraging hotel guests to revisit. Third, the emergence of multi-brand loyalty represents a potential for DMOs to distinguish a destination as having multiple different hotel chains or offering the same type of vacation in different places in a specific destination. Also, this can help to develop horizontal loyalty between different types of offerings, such as connecting the production of local goods and selling them through hotel chains in a destination. Fourth, as experiential loyalty is becoming important, DMOs can focus on developing destinations with a specific vacation style that offers experiences, such as adventurous destinations, heritage destinations or party destinations.

5. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The conducted research contributes to the field of loyalty in several ways. First, it provides detailed insight into research design/methods used in loyalty research in the field of tourism and hospitality business. It implies that loyalty is researched as loyalty types, consisting of: (multi) destination loyalty, hotel (brand) loyalty, loyalty (frequency) programmes and event (festival) loyalty. The majority of papers in the field of tourism and hospitality business have researched destination loyalty, with low emphasis on event (festival) loyalty. Past research has approached loyalty through different modes of expression, such as conative, affective and cognitive loyalty, and has also provided insight into future tourist behaviour based on different loyalty intentions, such as intention to recommend, switch and complain. Second, the paper offers an overview of locations where loyalty research in the field of tourism and hospitality has been conducted, indicating that the majority of research has been conducted in Asia and that more loyalty research in the field of tourism and hospitality business needs to be carried out on the African continent and in Australia. Also, the use of online research in the hospitality industry has great potential for further development. Third, the paper points out loyalty issues that have large potential for further research in the future.

Based on the literature review, it is possible to conclude that there is a lack of papers in which a larger number of units or destinations are researched. In order to understand multi-brand loyalty or multi-destination loyalty, research should involve several destinations simultaneously. Therefore, important questions that need to be covered are: What is the level of acceptance of multi-brand loyalty from the tourism supply perspective? Are there any tourist needs and wants for this type of loyalty, and do control variables such as gender, age, nationality and market distance exert any influence?

With a new loyalty perspective, the individual benefit of the company is surpassed when loyalty is more of a social benefit. Nevertheless, loyalty continues to reflect the logic that underpins every type and manner of loyalty expression: "The costs of acquiring new guests are 5-10 times greater than the retention of regular ones (Gummesson 1995)”. The key difference is that the benefit of retaining loyal guests is dispersed over multiple levels, which needs to be further explored within future scientific research.

Further research should also focus on guests who will claim to have no intention of coming to hotel X or will not recommend hotel X, but will still visit destination XY because they are loyal to the destination itself. It is also reasonable to assume there are guests who are loyal only to their own holiday style, e.g. sailing, regardless of the destination or brand. With regard to past research it is proposed that further research could also focus on researching mutual exclusivity. For example, does brand loyalty exclude destination loyalty, and vice versa? Some interesting research questions related to this topic that future research could also answer are: Are there any differences in expressing loyalty depending on the type of loyalty? Are factors that determine loyalty toward the destination equal to factors that determine loyalty toward a service provider or a holiday style?

Research in the tourism and hospitality industry as well as research in other industries has confirmed that differences exist in loyalty among younger and older generations. The young generation is focused more on discovering new destinations and less on loyalty (Petrick 2002).Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil (2018) have confirmed the relationship between age and destination loyalty – the older the age, the greater the destination loyalty. The importance of identifying differences within generational groups is reflected in the need to reorganize the core loyalty management tools/loyalty programme tools. For example, if it is determined that younger guests are not loyal to a single brand, it is necessary to ascertain whether there is general disloyalty or loyalty to a specific form of vacation, e.g., to their own specific experience, etc., and what are the possibilities of establishing a multi-brand loyalty programme intended for younger generations. Other research questions that could be also addressed are: How will the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) affect loyalty programme development? Is there a need for a multi-brand loyalty programme on the tourism market? What are the limitations and opportunities for introducing multi-brand loyalty programmes?

This paper has three limitations. First, data were collected only on the Web of Science platform with SSCI, excluding other potentially important studies for understanding emerging issues in this field. Second, clusters were not distributed equally, which might cause a different perspective of the loyalty types and misrepresent the smallest cluster (event loyalty). Third, as suggested bySchuckert et al. (2015), the authors neglected articles in other languages, conference articles, conference reports, book reviews, abstracts, editor prefaces, Internet columns and book chapters. Thus, further research should also consider the perspective of professional papers, not only that of scientific papers in highly ranked scientific journals.